Abstract

Opiates exacerbate HIV-1 Tat1-72–induced release of key proinflammatory cytokines by astrocytes, which may accelerate HIV neuropathogenesis in opiate abusers. The release of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1 or CCL2), in particular, is potentiated by opiate-HIV Tat interactions in vitro. Although MCP-1 draws monocytes/macrophages to sites of CNS infection, and activated monocytes/microglia release factors that can damage bystander neurons, its role in neuroAIDS progression in opiate abusers, or non-abusers, is uncertain. Using a chemotaxis assay, N9 microglial cell migration was significantly greater in conditioned medium from mouse striatal astrocytes exposed to morphine and/or Tat1-72 than in vehicle-, μ opioid receptor (MOR) antagonist-, or inactive, mutant TatΔ31-61-treated controls. Conditioned medium from astrocytes treated with morphine and Tat caused the greatest increase in motility. The response was attenuated using conditioned medium immunoneutralized with MCP-1 antibodies, or medium from MCP-1−/− astrocytes. In the presence of morphine (time-release, subcutaneous implant), intrastriatal Tat increased the proportion of neural cells that were astroglia and F4/80+ macrophages at 7 days post-injection. This was not seen following treatment with Tat alone, or with morphine plus inactive TatΔ31-61 or naltrexone. Glia displayed increased MOR and MCP-1 immunoreactivity following morphine and/or Tat exposure. The findings indicate that MCP-1 underlies most of the response of microglia, suggesting that one way in which opiates exacerbate neuroAIDS is by increasing astroglial-derived proinflammatory chemokines at focal sites of CNS infection and promoting macrophage entry and local microglial activation. Importantly, increased glial expression of MOR can trigger an opiate-driven amplification/positive feedback of MCP-1 production and inflammation.

Keywords: AIDS, chemokines, μ-opioid receptors, drug abuse, neuroimmunology, CNS inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Among HIV-infected individuals, injection drug users are at greater risk than non-users in developing HIV associated dementia (HAD) as well as other opportunistic infections. In addition to experimental findings, epidemiological studies are also beginning to establish links between opiate drug use and AIDS progression (Sheng et al., 1997; Donahoe and Vlahov, 1998), although the extent to which opiates per se contribute to AIDS progression has been controversial (Everall, 2004; Donahoe, 2004; Ansari, 2004). It is important to consider, however, that the effects of opiates on systemic immune function and HIV progression may not be readily extrapolated to their effects in the CNS, which appear to be preferentially vulnerable to opiate drug-HIV interactions (Bell et al., 1998; Nath et al., 2002; Donahoe, 2004; El-Hage et al., 2005). Opiate abuse has been shown to increase inflammatory events within the CNS (Anthony et al., 2004; Arango et al., 2004). Recent findings indicate that chronic opiate abuse increases simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)/simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) load in the serum and CSF of non-human primates (Kumar et al., 2004) and significantly worsens CD4+ cell recovery in clinical studies of HIV-infected individuals (Dronda et al., 2004), suggesting the progression of the disease is markedly affected by opiates. In addition to their function as potent analgesics and sedatives, opiates have been shown to possess a variety of immunomodulatory activities (Eisenstein and Hilburger, 1998; Gomez-Flores et al., 1999; Royal, III et al., 2003). Studies have shown that morphine has the ability to inhibit chemotaxis of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Makman et al., 1995), and blood monocytes (Perez-Castrillon et al., 1992; Stefano et al., 1993; Grimm et al., 1998). Studies in non-human primates have shown that opioids can inhibit chemokine-induced migration of leukocytes (Choi et al., 1999), as well as neutrophils and monocytes. Furthermore, opioids can inhibit the production of RANTES and the migration of microglial cells towards RANTES (Hu et al., 2000; Miyagi et al., 2000). On the other hand, opioids have been shown to facilitate chemotaxis in blood mononuclear cells (van Epps and Saland, 1984), as well as leukemia cells (Heagy et al., 1995). Opioid receptors are expressed on cells of the immune system such as the macrophages and T lymphocytes (Chuang et al., 1995; Wick et al., 1996; Sharp, 2003), as well as on microglia and astrocytes (Chao et al., 1997; Gurwell et al., 2001; Stiene-Martin et al., 2001). Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cell type in the CNS and play a key role in providing metabolic and trophic support for neurons (Fields and Stevens-Graham, 2002). In addition, astrocytes are essential mediators of neuroimmune function by expressing key cytokines, chemokines and their receptors, and by maintaining the blood brain barrier (Meeuwsen et al., 2003).

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1 or CCL2) is produced in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli by a wide variety of cells including macrophages, endothelial cells, microglia and activated astrocytes (Rollins, 1997). MCP-1 activates macrophage function and attracts monocytes, macrophages, basophils, mast cells, T lymphocytes, NK cells, and dendritic cells to sites of injury, both peripherally and within the brain (McManus et al., 2000). Numerous studies strongly suggest that chemokine expression in the CNS is responsible for various inflammatory and pathological conditions, including HIV encephalitis (Tyor et al., 1992; Conant et al., 1998; McManus et al., 2000), multiple sclerosis (MS) (McManus et al., 1998; Ransohoff et al., 2002), and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) (Mahad and Ransohoff, 2003). Although MCP-1 per se may not be intrinsically neurotoxic (Eugenin et al., 2003), it recruits and activates macrophages/microglia, whose secretions can be highly neurotoxic (Kaul et al., 2001; Persidsky and Gendelman, 2003; Mahad and Ransohoff, 2003).

Microglia are the resident macrophages in the brain, and believed to be functionally equivalent to monocytes or tissue macrophages of the somatic immune system (Gehrmann et al., 1995). Although it was shown by others that microglia have the ability to migrate to, differentiate, and to proliferate at sites of brain injury and inflammation (del Rio-Hortega, 1932), the actual signals involved in attracting microglia to these sites are not well established. Besides MCP-1, other factors that can induce microglial migration include serum complement component C5a and the β-chemokine RANTES (Chao et al., 1997; Hu et al., 2000). Although directed migration or chemotaxis of microglia may play a beneficial role in the elimination of damaged neurons or invading microorganisms (Brockhaus et al., 1993), activated microglia have the potential to release tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), nitric oxide, platelet activating factor, and other soluble factors, which can also be damaging to the neighboring neurons (Chao et al., 1992; Tyor et al., 1995; Nath, 1999; Xiong et al., 2000; Kaul et al., 2001; Persidsky and Gendelman, 2003).

In the present study, we describe for the first time a sequelae of glial-mediated intercellular events by which chronic opiate abuse may increase the severity of HIVE. Using a chemotaxis assay, we showed that astrocytes treated with morphine and HIV-Tat1-72 release chemoattractants that enhance N9 microglial cell mobility and that Tat injected into the striatum similarly recruited macrophages into the CNS parenchyma. MCP-1 was the predominant chemoattractant to cause microglial migration, although other factors are also involved. Opiate abuse exacerbates the toxic effects of HIV-1 Tat in astroglia, which in turn activates microglial function and by causing discordant neuron-glial interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

RPMI 1640 was purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Recombinant murine MCP-1 (JE/CCL2) and RANTES proteins were obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ), respectively. Morphine sulfate and naltrexone pelleted implants, as well as placebo (control) implants, were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, Drug Supply System, Bethesda, MD). The selective μ-opioid receptor (MOR) antagonist β-funaltrexamine (β-FNA) was purchased from RBI Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Tat preparation

The tat gene encoding the first 72 amino acids was amplified from HIVBRU obtained from Dr. Richard Gaynor through the AIDS repository at the NIH and inserted into an E. coli (PinPoint Xa-2) vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and expressed as a fusion protein. Tat1-72 was cleaved from the fusion protein-using factor Xa, purified on a column of soft release avidin resin, eluted from the column followed by desalting on a PD10 column as previously described (Ma and Nath, 1997). Endotoxin contamination was not detected in these preparations. Inactive Tat (TatΔ31-61) was generated from a deletion mutant of the active Tat plasmid, which lacked the sequence encoding the neurotoxic epitope (amino acids 31-61) of Tat1-72. Although endotoxins were below detectable range (i.e., <1 pg/ml) as determined using a commercially available assay (Limulus Amebocyte lysate assay; Associates of Cape Cod, MA), both Tat1-72 and inactive Tat (TatΔ31-61) are incubated in DetoxiGel™ Endotoxin removing Gel (Pierce, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer’s protocol to remove possible trace endotoxins.

Animals

Mice were purchased from ICR (Charles River Inc., Charles River, MA). For experiments using astrocytes derived from MCP-1 deficient mice, wild type (C57BL/6) and MCP-1−/− strains were bred and maintained as previously described (Ambati et al., 2003). In all experiments, mice were anesthetized and/or euthanized in accordance with NIH and local University of Kentucky IACUC guidelines, which minimizes the number of mice used and their possible discomfort.

Mixed glia cultures

Astroglial-enriched cultures were prepared using 1–4-day-old mice. Briefly, animals were anesthetized with ether and decapitated. Striata were aseptically isolated and cells pooled from 2–4 mice. Growth medium favoring astroglial enrichment consisted of Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM; GIBCO) supplemented with glucose (27 mM), Na2HCO3 (6 mM), HEPES (10 mM) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; JRH Biosciences). Cells were maintained in 12-well plates for 7–14 days in vitro at 35–36°C in 5% CO2/95% air at high humidity. Mixed cultures treated with leucine methyl esterase to deplete microglia were comprised of > 98% astrocytes and an insignificant number of microglia as determined by staining of glial fibrillary acidic protein and CD11b, respectively. We have previously characterized the proinflammatory response of astrocytes and microglia to morphine and/or Tat exposure using cytokine antibody arrays and/or RT-PCR (El-Hage et al., 2005).

A stable N9 microglial cell line was maintained as previously described (Bruce-Keller et al., 2000). Although cultured cell lines may not reflect all properties of in vivo microglia, N9 cells have been extensively assessed to ensure that they express typical markers of resting primary mouse microglia (Tanabe et al., 1997; Bruce-Keller et al., 2000; Bruce-Keller et al., 2001; Chang and Liu, 2001; Coraci et al., 2002; Dimayuga et al., 2003). In addition, N9 cells display patterns of intracellular signaling (Lockhart et al., 1998; Platten et al., 2003), NFkB activation (Bonaiuto et al., 1997), proliferation (Zhang et al., 2003), Tat responsiveness (Tanabe et al., 1997; Bruce-Keller et al., 2001; Cui et al., 2002), and neurotoxin release (Bruce-Keller et al., 2000; Bruce-Keller et al., 2001; Dimayuga et al., 2003; Lorenz et al., 2003), similar to microglia. N9 microglial cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate, with HEPES (10 mM) and 10% (v/v) FBS. Cells were maintained in vitro at 35–36°C in 5% CO2/95% air at high humidity and passaged every 4–5 days.

Treatment of astrocyte cultures

Astrocytes were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells in 500 μl per well in a 12-well culture plate or 1×105 cells in 1 ml per well in 6-well plates. The original media was removed, and the cells were cultured in sera free media in the presence or absence of morphine (1 μM) ± Tat1-72 (100 nM), or Tat (Δ31-61) (100 nM) at 35–36°C in 5% CO2/95% air at high humidity. After 12 h of incubation, supernatant (conditioned medium) was collected, centrifuged to remove contaminating cells, and stored at −80 °C until further use. In some cases, cultures were also pre-treated with the MOR antagonist β-FNA (1.5 μM) 30–60 min prior to addition of morphine and/or Tat.

Motility assay

A 48-well micro-chemotaxis chamber (AP48 Micro Chemotaxis Chamber; Neuro Probe, Cabin John, MD) was used to measure changes in motility of N9 microglial cells in response to supernatants from treated astrocytes, or the chemoattractants MCP-1 and RANTES. Motility, which is an important component of chemotaxis, was assayed as previously described with minor modifications (Chao et al., 1997; Hu et al., 2000). 105 N9 microglial cells were placed in the upper chamber and exposed to 25 μl of supernatant placed in the lower chamber for 3 h. The upper and lower compartments of the micro-chemotaxis chambers were separated by a 10-μm pore diameter, polyvinylpyrrolidine-free polycarbonate filter. Supernatants from untreated astrocytes or astrocytes treated with mutant TatΔ31-61 were used as negative controls, while recombinant MCP-1 (1–1000 ng/ml) and RANTES (1-500 ng/ml) were used as positive controls. The concentrations of the recombinant proteins used were based on previously published results (Taub et al., 1995) and assessed empirically in our system. After 3 h incubation, the non-migrating cells on the filter were gently removed with a cell scraper from the upper surface of the filter, and cells on the lower surface were fixed in methanol and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The number of cells migrating was examined microscopically using a 100X, oil immersion objective (Nikon Diaphot microscope). For individual determinations in each treatment group, the data represent the mean number of cells ± SEM migrating in five random fields (4,000 μm2) within 3 h, and all measurements were performed in triplicate in each experiment. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from at least 3 experiments.

MCP-1 blocking assay

To evaluate the extent to which astroglial-derived MCP-1 was mediating chemotaxis, MCP-1 activity was blocked by immunoneutralization adding an anti-MCP-1 monoclonal antibody (MCP-1; MAB479, R&D Systems) overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies were added to conditioned medium to final concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1 and 10 μg/ml. Following incubation with anti-MCP-1 antibodies, the medium is centrifuged prior to use. The movement of N9 microglial cells (105 cells/well) loaded into the upper chamber was measured in response to the MCP-1 depleted medium loaded into the lower well of the micro-chemotaxis chamber.

Stereotaxic injection of Tat and subcutaneous time-release opiate implants

Mice were anesthetized with 50–70 mg/kg of pentobarbital and then placed in a mouse stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL). Under aseptic conditions, artificial CSF-vehicle (control), 25 μg (2 nmol) of Tat1-72 or TatΔ31-61 was injected intrastriatally using a 30-gauge syringe (Hamilton Co., Reno, NV). Tat was introduced in a 1-μl volume of artificial CSF (Bansal et al., 2000; Aksenov et al., 2003). Striatal injections were made at the coordinates AP = +0.7 mm, ML = 2.0 mm and DV = −4.0 mm from bregma (Hof et al., 2000). Following the injection, the needle was allowed to remain in place for at least one minute before withdrawal to minimize Tat backflow along the needle tract as the syringe is withdrawn. Continuous, time-release pelleted implants (NIDA) were used to administer vehicle (placebo implant), morphine (25 mg), and/or naltrexone (30 mg). Immediately after stereotaxic injection and while still under anesthesia pelted implants are administered. Under aseptic conditions, the subscapular skin was lifted and a 3-mm incision made with a microscalpel. A 1.5-cm deep pocket is created with a forceps, placebo or opiate drug pellets are inserted, and the pocket closed with a single suture. Mice recovered from anesthesia under a warming lamp and were returned to their cages when they displayed normal activity. Pellets are depleted after 5 days. Therefore, mice were anesthetized and spent pellets replaced with fresh pellets on day 5. Mice were euthanized at 7 days following intrastriatal Tat and/or systemic opiate exposure. Although high Tat concentrations occur transiently at the site of injection, Tat has a relatively short half-life (Nath et al., 1999) and distributes in a gradient from the injection epicenter.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Mice were deeply anesthetized with 210 mg/kg pentobarbital i.p. and euthanized by intracardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 for 15 min (modified from Zamboni and De Martino, 1967). The brains were dissected and fixed for an additional 90 min before further processing. The forebrain, including the striatum, was serially sectioned (20 μm thick) in the coronal plane and sections collected at 180 μm-intervals throughout the striatum. To allow uniform penetration of the immunocytochemical reagents into 20 μm-thick tissue sections, sections were permeabilized by sequential treatment in 50% ethanol in 0.1 M PBS (v/v, pH 7.4) (30 min.), 70% ethanol in 0.1 M PBS (v/v, 30 min.), and 50% ethanol in 0.1 M PBS (v/v, 30 min.) followed by 3 × 5 min. rinses in 0.1 M PBS as described before (Jaeger et al., 1988; Hauser et al., 1994). MOR immunoreactivity was detected using rabbit anti-MOR affinity purified, polyclonal antisera (1:1000 dilution; PharMingen; San Diego, CA) and co-localized with anti-mouse monoclonal F4/80 (1:600 or 800 dilution, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) or with mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (1:300 dilution, Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis) monoclonal antibodies in the same cells as described (Stiene-Martin et al., 2001; Khurdayan et al., 2004). MCP-1 was detected using goat IgG antibodies against murine MCP-1 (sc-1784, 1:600 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Nestin was detected using an anti-mouse nestin monoclonal antibody (1:800 dilution; Chemicon Inc., Temecula, CA). Immunoreactivity was visualized with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:250 or 300 dilution; green fluorochrome; Molecular Probes, OR) or Cy3 (orange-red fluorochrome; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA; 1:300 dilution) as previously described (Khurdayan et al., 2004). Striatal tissue sections were counterstained with Hoechst 33342, which labels all cell nuclei.

Quantitative microscopy

A computer imaging system (Bioquant, Nashville, TN) interfaced with a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Optiphot, Melville, NY) and motorized X-Y and Z-axes stage controller (Ludl Electronic Products, Ltd., Hawthorne, NY) was used to systematically, but arbitrarily, sample cells near (300 ± 100 μm) and distant (600 ± 100 μm) from the site of Tat injection within the striatum. Macrophages/microglia (F4/80 immunoreactive cells) and astroglia (GFAP immunoreactive cells) were sampled from 10 uniformly spaced, optical disector frames in each section and 4 sections (40 disectors) were sampled for each mouse. All cells were sampled within a 30 μm × 30 μm optical disector using an arbitrary but systematic sampling procedure developed for stereology (Gunderson and West, 1988; Mouton, 2002; Schmitz and Hof, 2005). However, stereological analysis was not applied, because the non-uniform distribution of injected Tat makes it unrealistic to define a reference volume for the gradient of Tat within the striatum. Instead, the relative changes in the proportion of macrophages/microglia and astroglia ± MOR were determined from the total Hoechst-labeled cells. Because the introduction of a sterile syringe needle alone caused some glial changes along the needle tract as noted below, and may induce subtle injury/inflammatory changes elsewhere, treatment groups were always compared to vehicle-injected controls values at 300 ± 100 μm and 600 ± 100 μm from the injection epicenter. Typically, 300–400 cells total were sampled and average values recorded for each animal. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM from 4–6 mice per group. Digital photomicrographs were taken using a Spot 2 camera (Diagnostic Imaging, Midland, MI) attached to the Nikon Diaphot microscope or using a Leica, TCS SP confocal microscope.

RESULTS

Phenotypic characterization of N9 microglial cells and MCP-1−/− astrocytes

Although primary mouse astrocytes have been extensively characterized with respect to opioid phenotype, it is uncertain whether N9 microglial cells and astrocytes from MCP-1−/− mice express MOR, as well as key chemokines and their cognate receptors. To address this question, MOR expression was assessed in N9 microglial cells and MCP-1−/− astrocytes by RT-PCR (Fig. 1A) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 1B,C) (immunofluorescence for N9 cells not shown). We found that on average approximately 60 % of GFAP+ astrocytes stained positive for the presence of MOR protein (Fig. 1B,C). N9 microglia and MCP-1−/− astrocytes express MOR, as well as CCR2, CCR5, CCL5 mRNA transcripts. As expected, MCP-1 was detected in N9 cells but could not be detected in MCP-1−/− astroglia (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A–C: Primary MCP-1−/− (CCL2−/−) astrocytes and N9 microglial cells express μ-opioid receptor (MOR), as well as CCL5 and CCR5, and CCR2 mRNA (A). N9 cells additionally express MCP-1, which by design is absent in astrocytes from knock out mice (A). MOR immunoreactivity co-localized with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in MCP-1−/− astrocytes, which is similar to striatal astrocytes from wild type mice (B–C); photomicrographs at 100x magnification. D–I: Chemotactic response of N9 microglial cells to conditioned medium from morphine, Tat, or combined morphine and Tat-exposed astrocytes at 3 h in (D–I). Wright-Giemsa stained, N9 microglial cells (purple-blue stain) were assayed as they migrated across 10-μm pore diameter membranes (arrows) in 48-well micro-chemotaxis chambers as described (HI); photomicrographs taken using 40x (D–G) and 100x objectives (H–I).

Conditioned medium from morphine-exposed astrocytes can enhance N9 microglial cell motility

Previous studies have shown that MOR agonists can have paradoxical effects depending on experimental context and can act either as a suppressor of chemokine-mediated migration or as a weak chemoattractant for cell migration in the absence of exogenous chemokines (Chao et al., 1997; Grimm et al., 1998; Choi et al., 1999; Miyagi et al., 2000). In the present study, N9 microglial cells were placed in the upper wells of the chamber, and the movement of the cells toward the bottom of the chamber, which contained morphine concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 1 mM were determined. At 3 h, the number of migrating microglia was quantified by counting the cells that had passed through the filter (Fig. 1D–I). To assess whether this response was mediated through opiate receptors, the preferential MOR opiate receptor antagonist β-FNA was used to block MOR. Morphine induced chemotaxis in N9 microglial cells was concentration dependent and antagonist reversible (Fig. 2). At most concentrations 10 nM to 100 μM, morphine acted as a chemoattractant. An extremely high concentration (1 mM), morphine no longer enhanced cell migration compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 2). Importantly, however, even at high concentrations (100 μM), the effects of morphine could be blocked significantly by β-FNA suggesting the involvement of MOR (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of morphine or morphine and β-FNA on N9 microglial-cell chemotaxis. Morphine exposure caused concentration-dependent increases in cell migration that were prevented by concurrent exposure to the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) specific antagonist β-FNA (1.5 μM). Cell migration declined at the highest concentration of morphine. The data represent the mean ± SEM number of N9 cells migrating determined from 3 experiments (*P < 0.05 vs. vehicle controls; #P < 0.05 vs. treatment with morphine alone).

Conditioned medium from morphine and Tat-exposed astrocytes increases N9 microglial cell motility

To evaluate the function of the chemokine released on the migration of microglia in vitro, we used a 48-well micro-chemotaxis assay (Fig. 1D–E). Conditioned medium from treated astrocytes was added to the lower chamber and (105) microglial cells were added to the upper chamber. The number of N9 cells that had migrated across the filter was assessed at 3 h. Conditioned medium from astrocytes exposed to morphine (500 nM) or Tat 1-72 (100 nM) alone enhanced N9 cell migration compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3). Yet, when morphine was combined with Tat, cell migration was 2-fold greater than that seen with either morphine or Tat1-72 alone (Fig. 3). As a negative control, mutant TatΔ31-61 was used, and migration of microglia was significantly reduced by one-half compared to the migration with supernatant from cells treated with Tat1-72. Similarly, migration of microglia were significantly attenuated in the presence of supernatant treated with morphine plus TatΔ31-61 compared to morphine plus Tat 1-72 (Fig 3). Lastly, the chemotactic effects of combined morphine (1 μM) and Tat (2.92 ± 0.39-fold increase in migrating cells vs. vehicle-treated controls) were significantly attenuated by concurrent exposure to the MOR antagonist, β-FNA (1.5 μM) (0.95 ± 0.23-fold increase in migrating cells vs. vehicle-treated controls), suggesting the involvement of MOR (morphine + Tat vs. morphine + Tat + β-FNA, P < 0.013; Students t test); N9 microglial cell motility in vehicle-treated control cultures was 56.7 ± 11.6 cells. To assess whether some cells might have passed through the membrane and become suspended or adherent to the lower chamber, in a subset of experiments, we collected the medium from the lower chamber, centrifuged to concentrate potential cells, and counted using a hemacytometer. We also treated the lower chambers with methanol fixative and stain, and examined the bottom surface of the lower well for cells. Irrespective of treatment, i.e., vehicle-control, morphine (1 μM), Tat (100 nM), or morphine (1 μM) plus Tat (100 nM), cells were not observed in the medium in the lower chamber or in the lower chamber itself. Thus, at 3 h, N9 microglial cells that passed through the membrane filter remained adherent to the lower surface of the membrane filter.

Fig. 3.

Effect of MCP-1 immunoneutralization on the response of N9 microglial cells to conditioned medium from astrocytes pretreated with morphine (1 μM) and/or Tat1-72 (100 nM). Conditioned medium was incubated overnight with 0.1, 1, or 10 μg/ml or without (0 μg/ml) neutralizing anti-MCP-1 monoclonal antibodies before N9 cell chemotaxis was assayed. In the absence of anti-MCP-1 antibodies (0 μg/ml), Tat (**P < 0.015) or morphine plus Tat (***P < 0.001) caused significant increases in the migration of N9 microglial cells compared to vehicle-treated controls; morphine plus Tat exposure, in particular, differed markedly from all other groups (bP < 0.05) (ANOVA; post hoc Duncan’s test). By contrast, conditioned medium from astroglia exposed to inactive, mutant TatΔ31-61 (Tat-mut; 100 nM) or morphine plus TatΔ31-61 failed to enhance chemotaxis and showed significantly reduced migratory rates compared to morphine plus Tat1-72 (#P < 0.05). The effect of morphine plus Tat1-72 could be significantly reduced by the highest concentration of immunoneutralizing MCP-1 monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/ml), but not by 0.1 or 1 μg/ml amounts. The antibodies themselves had no effect on migration (*P<0.05). The data are expressed as the fold-increase in the number of migrating N9 cells compared to conditioned medium from vehicle-treated (control) astrocytes ± SEM. Note, during the time required for immunoneutralization, there is an obligate attenuation of the overall effects of astrocyte-conditioned medium on N9 cell migration (see text).

Astrocyte-derived MCP-1 mediates N9 microglial motility

In previous studies (El-Hage et al., 2005), we observed significant increases in the release of MCP-1 and RANTES proteins in the supernatant of astrocytes 12 h after treatment with morphine and Tat1-72. To determine whether migration of microglia in our system was specifically due to MCP-1, astrocyte-derived supernatant was incubated with anti-MCP-1 monoclonal antibodies ranging from 0.01 to 100 μg/ml to immunoneutralize MCP-1. Incubation with anti-MCP-1 monoclonal antibodies resulted in an inhibition of migration (Fig. 3). The greatest effect was observed when morphine plus Tat 1-72-treated astrocytes were incubated with 100 ng/ml anti-MCP-1 antibodies. Blocking this single chemokine significantly reduced the motility of N9 microglia to the astrocyte derived supernatant, indicating the key role of MCP-1 and its cognate receptor CCR2 in microglial migration.

It is important to note that motility was attenuated during the overnight incubation necessary to immunoabsorb MCP-1. Presumably this results from the degradation or hydrolysis of the chemokines released into the medium. This likely explains why N9 microglial chemotaxis was less robust following exposure to conditioned medium from morphine-treated (1 μM) astrocytes incubated for 12 h at 4°C (Fig. 3) compared to fresh conditioned medium (Fig. 2).

β-chemokines increase N9 microglial cell motility

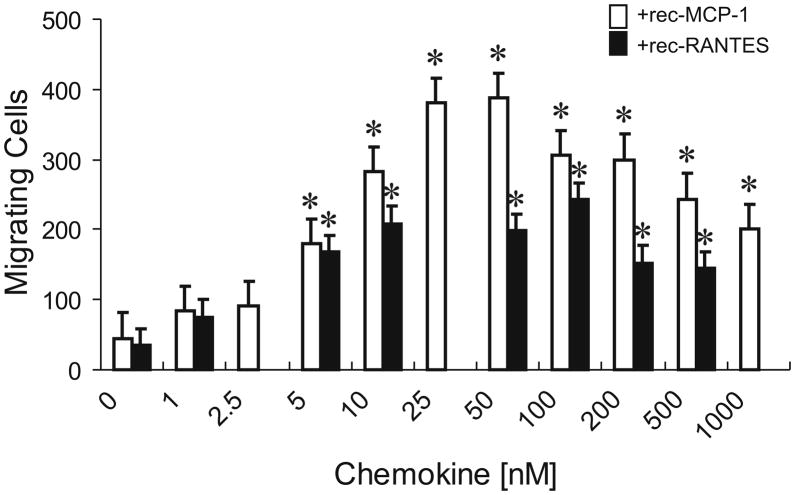

To determine whether MCP-1 or RANTES alone were sufficient to increase microglial N9 cell migration, we examined the effect of exogenous chemokines on microglial migration. N9 microglial cells (105) were continuously exposed to MCP-1 or RANTES at a wide range of concentrations. At 3 h following exposure, the number of microglia that had migrated across the filter were quantified. As shown in Fig. 4, there was low level of microglial migration in the absence of exogenously added chemokine. MCP-1 induced the migration of microglia in a dose-dependent manner with concentrations ranging from 25–50 ng/ml MCP-1 resulting in maximal migration (Fig. 4). Similar concentration-dependent increases in monocyte chemotaxis have been reported using recombinant mouse MCP-1 (Ernst et al., 1994; Hayashi et al., 1995). RANTES-induced N9 microglial migration was also concentration dependent, with a maximal response occurring at concentrations from 10–100 ng/ml RANTES.

Fig. 4.

MCP-1 and RANTES increase the migration of N9 microglial cells. N9 microglial chemotaxis was nominal when exposed to unsupplemented cell culture medium but showed significant, concentration-dependent increases when the medium was supplemented with recombinant MCP-1 (rec-MCP-1) or recombinant RANTES (rec-RANTES). Peak effects on migration occur with 25–50 ng/ml MCP-1 and 10–100 ng/ml RANTES. Cells were allowed to migrate for 3 h prior to harvest and the data represent the average number of migrating cells from 5 fields in n = 3 experiments.

Effect on microglial migration by morphine and Tat 1-72-treated MCP-1−/− astrocyte cultures

Striata from 1–4 day old MCP-1−/− mice were removed and astrocytes were seeded at a density of 105 cells in 500 μl per well in 12-well culture plates. The original medium was removed, and the cells were cultured in sera free media in the presence or absence of morphine (10−6 M), Tat1-72 (100 nM), or TatΔ31-61 (100 nM) at 35–36°C in 5% CO2/95% air at high humidity. Supernatants from treated or untreated MCP-1−/− astrocytes were added to the lower chamber and (105) N9 microglia were placed in the upper chamber. At 3 h, the number of microglia that had passed through the filter were quantified by Giemsa staining. Microglial migration was markedly reduced when conditioned medium from MCP-1−/− astrocytes was used (Fig. 5). When the conditioned medium from treated or untreated MCP-1−/− astrocytes was supplemented with recombinant MCP-1 (rec-MCP-1), microglial migration increased in a concentration-dependent manner in response to exogenous MCP-1. Maximal increases in microglial migration were seen with 50 ng/ml concentrations of MCP-1 and higher concentrations of the chemokine had no additional effect (Fig. 5). Although conditioned medium from MCP-1−/− astrocytes treated with morphine (1 μM) ± Tat1-72 (100 nM) or Tat Δ31-61 (100 nM) did induce higher rates of microglial migration compared to untreated MCP-1−/− astrocytes (Fig. 5), migration was significantly attenuated compared to that seen with similarly treated wild type astrocytes. This suggests that morphine and Tat in combination continued to potentiate the release of other chemokines such as RANTES or MCP-5 from the MCP-1 deficient astrocytes (El-Hage et al., 2005). When conditioned medium from morphine and Tat1-72–exposed MCP-1−/− astrocytes was supplemented with MCP-1 (50 ng/ml) full chemotactic function was restored and N9 microglial cell motility nearly doubled. The results indicate that MCP-1 mediates a significant proportion of the chemotactic signal released by astrocytes exposed to morphine and/or Tat, but that other factors are likely also involved.

Fig. 5.

Effects of conditioned medium from morphine-and/or Tat1-72-exposed MCP-1−/− astrocytes ± MCP-1 on N9 microglial migration. Despite the absence of MCP-1, conditioned medium from Tat1-72 (100 nM) or morphine (1 μM) plus Tat1-72 (**P<0.05 or ***P<0.01), but not TatΔ31-61 (100 nM), exposed astrocytes modestly, albeit significantly, increased N9 cell migration. However, when the conditioned medium was supplemented with recombinant MCP-1 (rec-MCP-1; 50 ng/ml), the effects of morphine and/or Tat were more pronounced (*P<0.05, vehicle-control vs. rec-MCP-1 treatment). Data represent the fold increase in N9 cell migration in response to conditioned medium from MCP-1−/− astrocyte supplemented with (rec-MCP-1) or without (vehicle) MCP-1, respectively, from n = 3 experiments.

Effects of systemic morphine and intrastriatal Tat administration

It is noteworthy that stereotaxic placement of a sterile syringe needle alone was sufficient to cause (i) gliotic changes (increased numbers of GFAP+ and F4/80 cells and cell processes) along the needle tract and (ii) increases in MOR immunoreactivity along the needle tract and at adjacent sites (Fig. 6). When Tat or morphine plus Tat were administered, the reactive glial changes and (ii) increases in MOR immunoreactivity at the injection epicenter and adjacent sites were more pronounced than in vehicle-injected controls (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the increases in the number of MOR+ cells appeared to be too great to be explained by observed increases in MOR+ macrophages/microglia and MOR+ astrocytes, suggesting that additional cell types contributed to increases in MOR immunoreactivity. Quantitative measures were not made at the injection epicenter because of the confounding effects of primary cell injury along the needle tract and the exceedingly high transient concentrations of Tat at the injection epicenter. Overall, the increase in the number of MOR+ cells at the injection site appeared to be significant and future studies are aimed at understanding the mechanisms underlying this response.

Fig. 6.

Increases in MCP-1, MOR, and GFAP immunoreactivity at and adjacent to the needle tract at 7 days following intrastriatal stereotaxic injection. Increases in MCP-1 and MOR immunoreactivity were present in injured cells along the needle tract in vehicle-treated controls (A–C). However, the extent of the cytopathologic changes surrounding the injection epicenter was greatly increased following Tat1-72 (25 μg) administration (D–F). MCP-1 was co-localized in subpopulations of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes (arrows) at or near the injection site in vehicle control- (G) and in Tat-injected (H,I) mice. MCP-1 is rarely seen in astrocytes in uninjured CNS. Although astrocytes were the predominant cell type possessing MCP-1 following injury or injury plus Tat exposure, non-astroglial cells resembling macrophages/microglia (arrowheads) also possessed MCP-1 immunoreactivity (I). Note that opiate and/or Tat-induced changes in astroglia and microglia were determined at 300 ± 100 and 600 ± 100 μm distances from the injection epicenter to avoid confounding effects of injury per se and transient high concentrations of Tat at the injection site (see Methods). Micrographs in A–F are montages taken using unmodified fluorescence microscopy, while those in G–I used confocal microscopy; scale bars: D = 100 μm (A & D same magnification); F = 100 μm (B, C, E & F same magnification); H = 20 μm (G & H same magnification); I = 20 μm.

Injections of Tat alone (25 μg) did not cause significant increases in the proportion of Hoechst-labeled cells that were macrophages/microglia (F4/80+) or astrocytes (GFAP+) near the site of Tat injection (300 μm ± 100 μm) at 7 days post exposure (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The proportion of Hoechst-labeled cells that were F4/80+ macrophages/microglia (A) and GFAP+ astroglia (B) increased dramatically near the Tat injection site (300 ± 100 μm) at 7-days following Tat and/or morphine (Morph) exposure (A,B). The effects were particularly evident in MOR immunoreactive microglia and astroglia (A,B). There were no changes in the proportion of microglia (±MOR) or astroglia (±MOR) distant (600 ±100 μm) from the site of Tat injection (not shown); *P < 0.05 vs. controls; #P < 0.05 vs. combined morphine and Tat exposure. Alternatively, conditioned medium from astroglia exposed to morphine plus inactive, mutant TatΔ31-61 (Tat-mut; 100 nM) or morphine plus Tat1-72, and naltrexone (NTX) failed to enhance chemotaxis and showed significantly reduced migratory rates compared to morphine plus Tat1-72 (#P < 0.05 vs. controls).

The lack of marked effects in astroglia (irrespective of whether they expressed a MOR phenotype) were not entirely surprising since intrastriatal Tat (50 μg) was previously found to cause an approximate 50% increase proportion of Hoechst-labeled cells that were GFAP+ at 7 days post injection in rat striatum (Bansal et al., 2000; Aksenov et al., 2003), while lower concentrations do not consistently increase GFAP immunoreactivity at 7 days (Bansal et al., 2000). It is important to note that 5 μg amounts are sufficient to cause a lesion at the site of injection (Bansal et al., 2000); therefore, 25 μg used in the present study was presumed sufficient to induce toxicity and likely to be at or near the threshold for inducing astrocytic changes in the striatum. Similarly, a lack of Tat induced increases in microglia (±MOR) might be anticipated based on prior work showing relative increases in OX-42-labeled cells at 24 h, but not at 7 days, post Tat injection (50 μg) in rat striatum (Aksenov et al., 2003).

Unlike findings with Tat alone, mice treated with time-release morphine implants in combination with intrastriatally injected Tat (25 μg) showed significant increases proportion of Hoechst-labeled cells that were F4/80+ macrophages/microglia near the site of injection compared to sham-injected mice receiving placebo or naltrexone implants, or mice receiving morphine and injected intrastriatally with inactive, mutant Tat (Fig. 7). Although systemic morphine exposure or intrastriatal injections of Tat alone tended to increase the proportion of F4/80+ macrophages near the site of stereotaxic injection, this effect was perhaps even more pronounced when MOR+ F4/80+ macrophages were assessed suggesting a selective response by the subpopulation of MOR+ macrophages. Importantly, F4/80+ macrophages expressing MOR+ were about 2-fold more likely to be near the site of Tat injection in morphine-exposed animals compared to sham-injected mice receiving placebo implants (Fig. 7). Significant increases in macrophages were not seen when Tat and morphine-treated mice additionally received naltrexone time-release implants (Fig. 7). Similarly, morphine failed to induce significant increases in F4/80 macrophages when an inactive mutant Tat was stereotaxically injected (Fig. 7).

Intrastriatal injections of Tat (25 μg) in mice treated with time-release morphine implants significantly increased the proportion of Hoechst-labeled cells that were GFAP+ astroglia near the site of injection compared to stereotaxically sham-injected mice receiving placebo or naltrexone implants alone (Figs. 6–7). Although systemic morphine exposure or intrastriatal injections of Tat alone tended to increase the proportion of total astroglia near the site of injection, this effect was equally pronounced when MOR+ astroglia were assessed, suggesting a similar response by both MOR and non-MOR subpopulations. Importantly, in combination morphine and Tat exposure caused about a 2-fold significant increases in GFAP+ astroglia compared to sham-injected, placebo controls—irrespective of whether the astroglia expressed MOR.

Although there was some tendency for combined morphine and Tat treatment to increase the proportion of Hoechst-labeled cells that were macrophages (F4/80+) and astroglia (GFAP+) to differ at locations distant from the injection site (600 ± 100 μm) within the striatum, these trends were not significant and the data are not shown for this reason. Thus, the systemic morphine selectively affected cells more proximate to the injection site where the Tat insult is greatest.

Lastly, to assess whether morphine and Tat-induced increases in the proportion of cells that were macrophages were accompanied by focal increases in proinflammatory chemokines, MCP-1 immunoreactivity was examined in alternative sections from the same morphine and/or Tat injected mice as in the GFAP and F4/80 immunostaining studies above. The results show focal increases in MCP-1 immunoreactivity adjacent to sites of Tat injections (Fig. 6). This was even more evident in striata exposed to morphine plus Tat where seemingly greater numbers of cells were MCP-1+ (data not shown), although quantitative microscopy is needed for confirmation. When MCP-1 was co-located with GFAP, MCP-1-immunoreactive astrocytes were apparent near the site of Tat injection (Fig. 6G–I), but to a lesser extent at striatal sites more distant from the lesion. Moreover, other non-GFAP-expressing cells that resembled macrophages/microglia also displayed MCP-1 immunoreactivity (Fig. 6I).

Interestingly, MOR was readily colocalized in many MCP-1-expressing cells (Fig. 6A–F). MOR was expressed by a large proportion of astroglia (Fig. 8A–D) and macrophages/microglia (Fig. 8E) near the injection site. Many of these astrocytes in particular appeared to co-express MCP-1 and MOR (El-Hage et al, in preparation). A subset of the MOR+ cells near the injection site also possessed nestin immunoreactivity (Fig. 8F–G). The nestin immunoreactive cells were small, with scant cytoplasm and appeared at or adjacent to blood vessels near sites of Tat injection and/or inflammation.

Fig. 8.

MOR immunoreactivity in cells within the striatum at 7 days following systemic morphine and/or intrastriatal Tat exposure. Combined morphine (25 mg time-release, subcutaneous implant) and intrastriatal Tat injection (25 μg) dramatically increased MOR immunoreactivity in a several cell types near (300 ± 100 μm) the site of Tat injection (A–D, F–H). MOR was readily localized in subpopulations of astrocytes (GFAP+) (A–D; arrows in B–D), macrophages/microglia (F4/80+) (E), and in nestin-expressing cells (arrows show the same cells in F–G). Subsets of neurons within the striatum (identified by neuronal nuclear antigen immunoreactivity) normally express MOR immunoreactivity (not shown). Circulating leukocytes, which may be monocytes/incipient macrophages, also expressed MCP-1 (arrow in H); GFAP+ astroglial processes approximate the wall of a blood vessel (arrowheads in H). Hoechst counterstains all cells (blue); Micrographs in B–E were taken using confocal microscopy, while those in A, F–H used unmodified fluorescent microscopy; scale bars: A = 100 μm; B & D =20 μm (C & D same magnification); E, G & H = 10 μm (F & G same magnification).

DISCUSSION

Our data show that chemokines released from astrocytes exposed to morphine and/or HIV-1 Tat1-72 are major factors in recruiting macrophages and microglia, and that morphine potentiates the effects of Tat in inducing microglial chemotaxis. MCP-1, in particular, is a major contributor in microglial chemotaxis. Although morphine and/or Tat still caused chemotactic effects following MCP-1 immunoneutralization or in the presence of MCP-1−/− astroglia, chemotaxis was significantly attenuated in the absence of MCP-1. This suggests that while alternative astrocyte-derived chemokines such as RANTES and MCP-5 contribute to morphine and/or Tat-induced chemoattraction (El-Hage et al., 2005), MCP-1 is the principal chemotactic signal, accounting for about one-half to two-thirds of the N9 microglial cell response. Furthermore, mice injected intrastriatally with Tat and given systemic morphine show focal increases in macrophages/microglia at the Tat injection site, suggesting that chemokines are released at the injection epicenter. Focal increases in MCP-1 immunoreactivity occur in astroglia (and macrophages/microglia) at the site of Tat injection support this notion. Moreover, the relative intensity of MCP-1 immunoreactivity is highest at the injection site and appears to increase with concurrent morphine treatment.

Monocytes, macrophages, and microglia have long-been known to be direct targets for opioids (Peterson et al., 1991; Chao et al., 1996; Sheng et al., 1997; Roy et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 1998; Rogers and Peterson, 2003). Opiates typically act by directly inhibiting macrophage/microglial function. For example, opium was shown to suppress chemotaxis of guinea-pig phagocytes more than a century ago (reviewed by Vallejo et al., 2004). Early studies also showed that opioids at nanomolar or picomolar concentrations can directly induce chemoattraction (van Epps and Saland, 1984; Grimm et al., 1998). More recent studies have shown that opioids can inhibit the migration of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Makman et al., 1995) human blood monocytes (Stefano et al., 1993) and human microglia (Grimm et al., 1998; Hu et al., 2000). Opioid prevention of chemokine-mediated chemotaxis was also seen in studies with neutrophils and monocytes from non-human primates (Miyagi et al., 2000).

Our studies measure the response of N9 microglial cells to the secreted products of opiate-exposed astrocytes, rather then a direct effect of morphine on N9 cells themselves. Astrocytes are the most abundant cell type in the CNS and respond rapidly to neuronal injury and dysfunction (Fields and Stevens-Graham, 2002). Moreover, since little residual morphine is likely to remain when N9 cells are exposed to conditioned medium, any potentially direct inhibitory effects of morphine on N9 cells are absent in our studies. Alternatively, if the astrocyte conditioned medium is replenished with morphine, identical increases in N9 microglial chemotaxis are seen at 3 h compared to medium without morphine (El-Hage, unpublished). The intercellular signals from astrocytes seemingly override the direct, presumed competing effects of opiates on the N9 cells themselves. This is partially supported by our in vivo studies showing increased macrophage/microglial near sites of Tat injection despite continuous systemic morphine. The finding that conditioned medium from astrocytes treated with morphine elicits a bell-shaped concentration-dependent effect on N9 microglial cell migration is similar to concentration-dependent effects that have been reported in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Peterson et al., 1990; Peterson et al., 1991). At exceedingly high concentrations, such as 1 mM, morphine is likely to cross react with alternative non-MOR opioid and non-opioid receptors yielding unpredictable effects in astrocytes. The demonstration that increases in microglial mobility caused by conditioned medium from astrocytes exposed to morphine at concentrations ≤ 100 μM could be were blocked by β-FNA suggests that the effects were mediated by MOR. Thus, the present studies infer a mechanism by which macrophage/microglial homing to sites of inflammation in the CNS is mediated by opioid-induced chemokine production by astrocytes.

The present results agree with the long-standing notion that microglia play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of neuroAIDS. Not only are microglia sites of HIV propagation, but they likely modify neuropathogenesis through the release of cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-1 (IL-1), interferon-γ and nitric oxide synthase (Tyor et al., 1992; Sippy et al., 1995). Additionally, there are reports that the appearance of activated macrophages in white matter correlates positively with the presence of HIV dementia (Tyor et al., 1995; Bell, 1998; Epstein, 1998). Importantly, MOR agonists can potentiate HIV propagation in lymphocytes, microglial cells and monocytes (Peterson et al., 1990; Carr and Serou, 1995), and increase microglial activation in the present study. This is in general agreement with findings that microglial numbers are increased in some brain regions with drug abuse and this may be exaggerated by HIV (Bell et al., 2002) and more recent findings that opiate abuse may hasten macrophage turnover in the CNS of individuals with HIVE (Anthony et al., 2005).

MCP-1 is emerging as an important player in the pathogenesis of neuroAIDS (Sevigny et al., 2004; Letendre et al., 2004; Mankowski et al., 2004; Avison et al., 2004; Eugenin et al., 2005) and has established importance in other neuroinflammatory diseases such as MS (Ransohoff et al., 2003). MCP-1 levels are highly correlated with HIV dementia (Sevigny et al., 2004) and in neurobehavioral defects in SIV infected macaques (Mankowski et al., 2004).

Astrocyte activation is an early finding in patients with HIV infection (Navia et al., 1986), and may be followed by apoptosis (Petito and Roberts, 1995). In rodent models of neuro-AIDS, astrogliosis has been reported in rats injected intrastriatally with Tat at 7 days (Bansal et al., 2000), which coincides well with the period of peak astrogliosis in a SCID mouse model of neuroAIDS (Tyor et al., 1993; Persidsky et al., 1996). Interestingly, reactive astrocytic changes occur in the brains of heroin addicts even in the absence of HIV infection (Gosztonyi et al., 1993), although this may not be a consistent finding (Anderson et al., 2003) or may differ among brain regions (Anderson et al., 2003; Hauser et al., 2005b). Since both opiate drug abuse and HIV infection by themselves can cause pathological changes in astrocytes, it was a reasonable assumption that HIV plus opiates might act in concert to produce even greater astrocyte dysfunction. We have consistently found opiate-HIV interactions in astroglia (Khurdayan et al., 2004; El-Hage et al., 2005). As noted, opiates and HIV-1 Tat converge at the level of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i), and this is accompanied by increases MCP-1 and RANTES release in astroglia (El-Hage et al., 2005). The interactive changes in [Ca2+]i can be prevented by by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002, suggesting that synergistic increases in [Ca2+]i in astroglia are mediated by PI3K (El-Hage et al., 2005). Based on other evidence that opiates and Tat can both activate the PI3K-protein kinase B (PKB/Akt)-glycogen synthase kinase-3β pathway (Chu et al., 1996; Duckworth and Cantley, 1997; Lopez-Ilasaca et al., 1997; Polakiewicz et al., 1998; Scheid et al., 1999; Tan et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2003), we speculate that PI3K and Akt are involved in the interaction, although other possibilities exist (see Hauser et al., 2005b).

Significant increases in the number of GFAP-expressing astrocytes at 7 days following combined morphine and Tat exposure that were not evident with either morphine or Tat alone. Furthermore, the proportion of MOR+ astroglia specifically increased at the site of the lesion with morphine or morphine plus Tat exposure. This suggests that two different astroglial subpopulations exist (MOR versus non-MOR-expressing astroglia) (see Stiene-Martin et al., 1998), which likely respond differentially to opiates. Importantly, the local increases in the proportion of MOR-expressing astroglia (and macrophages/microglia) are likely to amplify the local tissue response to opioids; augmentation of some opioid actions has been noted transiently in the peripheral nervous system following injury or inflammation (Stein et al., 2003).

Although a 7-day-survival time may have been fortuitous for detecting synergistic changes in astrocytes following morphine plus Tat exposure, this may have been less optimal for detection of microglial changes, which may occur within 1–3 days following Tat injection (Aksenov et al., 2003). Assessing glial changes at 7 days post injection enabled us to compare our results directly with other published studies. A 7-day duration was additionally chosen because we assumed that a macrophage/microglial response would be secondary to synergistic morphine-Tat induced increases in Tat-induced astrocyte chemokine production (El-Hage et al., 2005), and we wished to allow sufficient time for macrophages/microglia to respond to an astroglial signal. Studies in progress are examining the timing of glial and neuronal changes subsequent to morphine-HIV exposure in detail and should provide additional clues regarding the sequelae of events underlying the altered pathogenesis.

The proportion of MOR-expressing cells dramatically increased following Tat injection and/or morphine exposure, which has not been previously reported in the CNS. In fact, the increases in the proportion of MOR-expressing Hoechst+ cells appeared to be greater than what could be explained by increases in MOR-expressing astroglia and microglia alone. This prompted additional characterization of the MOR+ cells at or near the site of Tat injection/inflammation. Besides neurons, astrocytes, and macrophages/microglia, other cell types such as endothelia, oligodendroglia and lymphocytes can express MOR. Recent evidence suggests that neural progenitors can migrate to sites of CNS injury (Sun et al., 2004; Imitola et al., 2004), while we found that a large percentage of neural progenitors express MOR and respond directly to the effects of opiates and HIV-1 Tat (Khurdayan et al., 2004). Nestin was screened because, besides being a marker for neural progenitors, recent findings have shown that the intermediate filament may also be a marker for immature hemopoietic cells (Mezey et al., 2000; Buzanska et al., 2002) and for endothelial cells during neovascularization subsequent to injury (Mokry et al., 2004; Amoh et al., 2004). Although the identity of the cell types involved in the response needs further assessment, increased MOR expression seemingly involves both CNS resident (non-GFAP expressing glia and endothelial cells) and non-resident (non-F4/80-expressing leukocytes) cell types.

The reasons why there is a coordinated and presumed transient response of the opioid system among disparate cell types is uncertain, but suggests that MOR and their cognate peptide ligands are involved in a common process related to Tat-induced inflammation. Equally important, the cellular injury caused by a sterile needle is sufficient to induce increases in MOR immunoreactivity in multiple cell types and this appears to be accompanied by overlapping increases in MCP-1 immunoreactivity. There are numerous reports of increased opioid receptor (Stein et al., 2003) and peptide (Przewlocki and Przewlocka, 2001; Stein et al., 2003) expression following peripheral nerve injury and/or inflammation, although increases in MOR in particular may differ among the different injury paradigms (see Walczak et al., 2005). By contrast, there are few reports of increased expression of endogenous opioid receptors, especially MOR, in response to CNS injury or disease, although upregulation in MOR/KOR following CNS tract lesions in non-human primates (assessed via PET imaging) (Cohen et al., 2000) and increases in KOR phosphorylation with neuropathic pain (Xu et al., 2004) have been reported. Increases in endogenous opioid peptide expression, especially prodynorphin- and proenkephalin-derived peptides (Naftchi, 1990; Mcmillian et al., 1994; Solbrig and Koob, 2004; Hauser et al., 2005a), as well as nociceptin/orphanin FQ (Witta et al., 2003), have also been noted in the CNS in response to injury, inflammation, or disease. Our results suggest that MOR upregulation is an intrinsic feature of CNS injury and this is coordinated with increases in MCP-1 expression.

From our present in vivo data, it is not possible to determine the sequence of events driving the cellular changes we observe. However, certain inferences can be made from our in vitro results. The initial astroglial response appears to be a direct effect of morphine and Tat in astrocytes and involves a loss of [Ca2+]i homeostasis and release of proinflammatory chemokines including MCP-1, RANTES, and MCP-5 (El-Hage et al., 2005). The most important consequence of this initial astroglial response may be to recruit macrophages/microglia. Importantly, this initial step is greatly exacerbated by opiates and seemingly results through direct actions of opiates on MOR-expressing astroglia, since it is observed in isolated astrocytes in vitro. Once activated, macrophages can release cytokines and cytotoxic substances that may further disrupt astroglial function through chronic inflammation and accompanying oxidative stress (Nath, 1999; Kaul et al., 2001; Persidsky and Gendelman, 2003), which may lead to a secondary astroglial response highlighted by lasting organizational changes in cell structure including reactive gliosis. Signals from neurons may also induce reactive alterations in astrocytes, which may provide additional positive feedback for driving inflammatory cascades. For example, morphine-induced changes in neurons can also contribute to reactive astroglial changes through protein kinase C-γ-mediated neuron-glial signaling (Narita et al., 2004). Macrophages/microglia and potentially neurons may contribute greatly to astrogliosis, which is not evident for at least one week following inoculation of SCID mice with HIV-infected human monocytes (Tyor et al., 1993; Persidsky et al., 1996).. Similar increases in the proportion of GFAP+ astrocytes were seen in the present study irrespective of whether they expressed MOR. This suggests that unlike initial increases in [Ca2+]i and cytokine release, which require MOR expression (El-Hage et al., 2005), the reactive cytological changes evident days later are equivalent in MOR and non-MOR astrocytes. We propose that astrocytes, through their initial response that includes the release of chemokines, are essential gatekeepers in triggering the synergistic inflammatory responses to opiates and HIV. Moreover, our findings also provide compelling evidence that besides being critical sensors for initiating opiate-HIV interactions, astrocytes continue to express MCP-1 at 7 days post exposure, which likely mediates sustained increases in macrophage/microglial recruitment and activation. This is likely to contribute markedly to spiraling inflammation and ensuing neurotoxicity. Assuming similar responses occur within the human CNS, morphine is likely to exacerbate the consequences of HIV infection through the recruitment and activation of additional macrophages/microglia at focal sites of infection beyond levels caused by HIV alone.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kenneth Martin, Celeste Dean, and Megan Campbell for expert technical assistance. We thank Dr. Avindra Nath for providing HIV-1 Tat and outstanding guidance and discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grants DA13278, DA19398 and P20RR015592.

Abbreviations

- CXCR

alpha chemokine receptor

- CCL

beta chemokine ligand

- CCR

beta chemokine receptor

- β-FNA

β-funaltrexamine

- EAE

experimental allergic encephalomyelitis

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HAD

HIV associated dementia

- HIVE

human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis

- IL

interleukin

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+

- MCP-1 or CCL2

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PI3-kinase

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKB/Akt

protein kinase B

- RANTES

regulated on activation; normal T cell expressed and secreted

- SHIV

simian-human immunodeficiency virus

- SIV

simian immunodeficiency virus

- Tat

transactivator of transcription

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

References

- Aksenov MY, Hasselrot U, Wu G, Nath A, Anderson C, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Temporal relationships between HIV-1 Tat-induced neuronal degeneration, OX-42 immunoreactivity, reactive astrocytosis, and protein oxidation in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 2003;987:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambati J, Anand A, Fernandez S, Sakurai E, Lynn BC, Kuziel WA, Rollins BJ, Ambati BK. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2003;9:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoh Y, Li L, Yang M, Moossa AR, Katsuoka K, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Nascent blood vessels in the skin arise from nestin-expressing hair-follicle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13291–13295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405250101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CE, Tomlinson GS, Pauly B, Brannan FW, Chiswick A, Brack-Werner R, Simmonds P, Bell JE. Relationship of Nef-positive and GFAP-reactive astrocytes to drug use in early and late HIV infection. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:378–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari AA. Drugs of abuse and HIV--a perspective. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony IC, Crawford DH, Bell JE. Effects of human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis and drug abuse on the B lymphocyte population of the brain. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:181–188. doi: 10.1080/13550280490444100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, Simmonds P, Bell JE. Does drug abuse alter microglial phenotype and cell turnover in the context of advancing HIV infection? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:325–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango JC, Simmonds P, Brettle RP, Bell JE. Does drug abuse influence the microglial response in AIDS and HIV encephalitis? AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S69–74. S69–S74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison MJ, Nath A, Greene-Avison R, Schmitt FA, Bales RA, Ethisham A, Greenberg RN, Berger JR. Inflammatory changes and breakdown of microvascular integrity in early human immunodeficiency virus dementia. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:223–232. doi: 10.1080/13550280490463532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal AK, Mactutus CF, Nath A, Maragos W, Hauser KF, Booze RM. Neurotoxicity of HIV-1 proteins gp120 and tat in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 2000;879:42–49. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JE. The neuropathology of adult HIV infection. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1998;154:816–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JE, Arango JC, Robertson R, Brettle RP, Leen C, Simmonds P. HIV and Drug Misuse in the Edinburgh Cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 2):S35–42. S35–S42. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200210012-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JE, Brettle RP, Chiswick A, Simmonds P. HIV encephalitis, proviral load and dementia in drug users and homosexuals with AIDS. Effect of neocortical involvement. Brain. 1998;121:2043–2052. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.11.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaiuto C, McDonald PP, Rossi F, Cassatella MA. Activation of nuclear factor-kappa B by beta-amyloid peptides and interferon-gamma in murine microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;77:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus J, Ilschner S, Banati RB, Kettenmann H. Membrane properties of ameboid microglial cells in the corpus callosum slice from early postnatal mice. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4412–4421. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04412.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Barger SW, Moss NI, Pham JT, Keller JN, Nath A. Pro-inflammatory and pro- oxidant properties of the HIV protein Tat in a microglial cell line: attenuation by 17 beta-estradiol. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1315–1324. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Keeling JL, Keller JN, Huang FF, Camondola S, Mattson MP. Antiinflammatory effects of estrogen on microglial activation. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3646–3656. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzanska L, Machaj EK, Zablocka B, Pojda Z, Domanska-Janik K. Human cord blood-derived cells attain neuronal and glial features in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2131–2138. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.10.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DJ, Serou M. Exogenous and endogenous opioids as biological response modifiers. Immunopharmacology. 1995;31:59–71. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JY, Liu LZ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists prevent 25-OH-cholesterol induced c-jun activation and cell death. BMC Pharmacol. 2001;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Hu S, Molitor TW, Shaskan EG, Peterson PK. Activated microglia mediate neuronal cell injury via a nitric oxide mechanism. J Immunol. 1992;149:2736–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Hu S, Peterson PK. Opiates, glia, and neurotoxicity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;402:29–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0407-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Hu S, Shark KB, Sheng WS, Gekker G, Peterson PK. Activation of mu opioid receptors inhibits microglial cell chemotaxis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:998–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Chuang LF, Lam KM, Kung HF, Wang JM, Osburn BI, Chuang RY. Inhibition of chemokine-induced chemotaxis of monkey leukocytes by mu-opioid receptor agonists. In Vivo. 1999;13:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Soncin F, Price BD, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Sequential phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 represses transcriptional activation by heat shock factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30847–30857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang TK, Killam KF, Jr, Chuang LF, Kung HF, Sheng WS, Chao CC, Yu L, Chuang RY. Mu opioid receptor gene expression in immune cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;216:922–930. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RM, Carson RE, Saunders RC, Doudet DJ. Opiate receptor avidity is increased in rhesus monkeys following unilateral optic tract lesion combined with transections of corpus callosum and hippocampal and anterior commissures. Brain Res. 2000;879:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant K, Garzino-Demo A, Nath A, McArthur JC, Halliday W, Power C, Gallo RC, Major EO. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in HIV-1 Tat-stimulated astrocytes and elevation in AIDS dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3117–3121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coraci IS, Husemann J, Berman JW, Hulette C, Dufour JH, Campanella GK, Luster AD, Silverstein SC, El-Khoury JB. CD36, a class B scavenger receptor, is expressed on microglia in Alzheimer’s disease brains and can mediate production of reactive oxygen species in response to beta-amyloid fibrils. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui YH, Le Y, Gong W, Proost P, Van DJ, Murphy WJ, Wang JM. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide selectively up-regulates the function of the chemotactic peptide receptor formyl peptide receptor 2 in murine microglial cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:434–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio-Hortega P. Microglia. In: Penfield W, editor. Cytology & cellular pathology of the nervous system. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Inc; 1932. pp. 482–534. [Google Scholar]

- Dimayuga FO, Ding Q, Keller JN, Marchionni MA, Seroogy KB, Bruce-Keller AJ. The neuregulin GGF2 attenuates free radical release from activated microglial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;136:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe RM. Multiple ways that drug abuse might influence AIDS progression: clues from a monkey model. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe RM, Vlahov D. Opiates as potential cofactors in progression of HIV-1 infections to AIDS. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronda F, Zamora J, Moreno S, Moreno A, Casado JL, Muriel A, Perez-Elias MJ, Antela A, Moreno L, Quereda C. CD4 cell recovery during successful antiretroviral therapy in naive HIV-infected patients: the role of intravenous drug use. AIDS. 2004;18:2210–2212. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth BC, Cantley LC. Conditional inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by wortmannin. Dependence on signal strength. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27665–27670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein TK, Hilburger ME. Opioid modulation of immune responses: effects on phagocyte and lymphoid cell populations. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Gurwell JA, Singh IN, Knapp PE, Nath A, Hauser KF. Synergistic increases in intracellular Ca2+, and the release of MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-6 by astrocytes treated with opiates and HIV-1 Tat. Glia. 2005;50:91–106. doi: 10.1002/glia.20148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LG. HIV neuropathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1998;40:107–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1998.tb01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst CA, Zhang YJ, Hancock PR, Rutledge BJ, Corless CL, Rollins BJ. Biochemical and biologic characterization of murine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Identification of two functional domains. J Immunol. 1994;152:3541–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenin EA, D’Aversa TG, Lopez L, Calderon TM, Berman JW. MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1299–1311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenin EA, Dyer G, Calderon TM, Berman JW. HIV-1 tat protein induces a migratory phenotype in human fetal microglia by a CCL2 (MCP-1)-dependent mechanism: Possible role in NeuroAIDS. Glia. 2005;49:501–510. doi: 10.1002/glia.20137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP. Interaction between HIV and intravenous heroin abuse? J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields RD, Stevens-Graham B. New insights into neuron-glia communication. Science. 2002;298:556–562. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5593.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;20:269–287. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00015-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Flores R, Suo JL, Weber RJ. Suppression of splenic macrophage functions following acute morphine action in the rat mesencephalon periaqueductal gray. Brain Behav Immun. 1999;13:212–224. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1999.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosztonyi G, Schmidt V, Nickel R, Rothschild MA, Camacho S, Siegel G, Zill E, Pauli G, Schneider V. Neuropathologic analysis of postmortal brain samples of HIV-seropositive and -seronegative i.v. drug addicts. Forensic Sci Int. 1993;62:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(93)90052-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm MC, Ben-Baruch A, Taub DD, Howard OM, Wang JM, Oppenheim JJ. Opiate inhibition of chemokine-induced chemotaxis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson HJG, West MJ. The new stereological tools: Disector, fractionator, nucleator and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988;96:857–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwell JA, Nath A, Sun Q, Zhang J, Martin KM, Chen Y, Hauser KF. Synergistic neurotoxicity of opioids and human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat protein in striatal neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2001;102:555–563. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00461-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser KF, Aldrich JV, Anderson KJ, Bakalkin G, Christie MJ, Hall ED, Knapp PE, Scheff SW, Singh IN, Vissel B, Woods AS, Yakovleva T, Shippenberg TS. Pathobiology of dynorphins in trauma and disease. Front Biosci. 2005a;10:216–235. doi: 10.2741/1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser KF, El-Hage N, Buch S, Berger JR, Tyor WR, Nath A, Bruce-Keller AJ, Knapp PE. Molecular targets of opiate drug abuse in neuroAIDS. Neurotox Res. 2005b doi: 10.1007/BF03033820. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser KF, Gurwell JA, Turbek CS. Morphine inhibits Purkinje cell survival and dendritic differentiation in organotypic cultures of the mouse cerebellum. Exp Neurol. 1994;130:95–105. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Luo Y, Laning J, Strieter RM, Dorf ME. Production and function of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and other beta-chemokines in murine glial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;60:143–150. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heagy W, Duca K, Finberg RW. Enkephalins stimulate leukemia cell migration and surface expression of CD9. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1366–1374. doi: 10.1172/JCI118171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Young WG, Bloom FE, Belichenko PV, Celio MR. Comparative Cytoarchitectonic Atlas of the C57BL/6 and 129/Sv Mouse Brains. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Sheng WS, Ehrlich LC, Peterson PK, Chao CC. Cytokine Effects on Glutamate Uptake by Human Astrocytes. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2000;7:153–159. doi: 10.1159/000026433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imitola J, Comabella M, Chandraker AK, Dangond F, Sayegh MH, Snyder EY, Khoury SJ. Neural stem/progenitor cells express costimulatory molecules that are differentially regulated by inflammatory and apoptotic stimuli. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63720-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger CM, Kapoor R, Llinás R. Cytology and organization of rat cerebellar organ cultures. Neuroscience. 1988;26:509–538. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DM, Tucker BA, Rahimtula M, Mearow KM. The synergistic effects of NGF and IGF-1 on neurite growth in adult sensory neurons: convergence on the PI 3-kinase signaling pathway. J Neurochem. 2003;86:1116–1128. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Garden GA, Lipton SA. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature. 2001;410:988–994. doi: 10.1038/35073667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurdayan VK, Buch S, El-Hage N, Lutz SE, Goebel SM, Singh IN, Knapp PE, Turchan-Cholewo J, Nath A, Hauser KF. Preferential vulnerability of astroglia and glial precursors to combined opioid and HIV-1 Tat exposure in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:3171–3182. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Torres C, Yamamura Y, Rodriguez I, Martinez M, Staprans S, Donahoe RM, Kraiselburd E, Stephens EB, Kumar A. Modulation by morphine of viral set point in rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus and simian-human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2004;78:11425–11428. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11425-11428.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Singh KK, de AS, Zimmerman J, Spector SA, Grant I, Ellis R. The monocyte chemotactic protein-1 -2578G allele is associated with elevated MCP-1 concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart BP, Cressey KC, Lepagnol JM. Suppression of nitric oxide formation by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in murine N9 microglia. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:879–889. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ilasaca M, Crespo P, Pellici PG, Gutkind JS, Wetzker R. Linkage of G protein-coupled receptors to the MAPK signaling pathway through PI 3-kinase gamma. Science. 1997;275:394–397. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz P, Roychowdhury S, Engelmann M, Wolf G, Horn TF. Oxyresveratrol and resveratrol are potent antioxidants and free radical scavengers: effect on nitrosative and oxidative stress derived from microglial cells. Nitric Oxide. 2003;9:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Nath A. Molecular determinants for cellular uptake of Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in brain cells. J Virol. 1997;71:2495–2499. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2495-2499.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad DJ, Ransohoff RM. The role of MCP-1 (CCL2) and CCR2 in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) Semin Immunol. 2003;15:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makman MH, Bilfinger TV, Stefano GB. Human granulocytes contain an opiate alkaloid-selective receptor mediating inhibition of cytokine-induced activation and chemotaxis. J Immunol. 1995;154:1323–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]