Abstract

A CuI complex of 3-ethynyl-phenanthroline covalently immobilized to an azide-modified glassy carbon surface is an active electrocatalyst for the 4-electron reduction of O2 to H2O. The rate of O2 reduction is 2nd order in Cu coverage at moderate overpotential, suggesting that two CuI species are necessary for efficient 4-electron reduction of O2. Mechanisms for O2 reduction are proposed that are consistent with the observations for this covalently immobilized system and previously reported results for a similar physisorbed CuI system.

Discrete copper complexes are potential catalysts for the 4-electron reduction of O2 to water in ambient temperature fuel cells as evidenced by Cu-containing fungal laccase enzymes that rapidly reduce O2 directly to water at a trinuclear Cu active site at remarkably positive potentials.1-5 Several groups have studied molecular Cu complexes immobilized onto electrode surfaces as an entry into the study of 4-electron O2 reduction.6-19 In particular, physisorbed CuI(1,10-phenanthroline), Cu(phenP), reduces O2 quantitatively by 4 electrons and 4 protons to water.8-10 Anson, et al., determined that this reaction was 1st order in Cu coverage, suggestive of a mononuclear Cu site as the active catalyst.8,10

In the present study, similar CuI complexes are covalently attached to a modified glassy-carbon electrode surface to form a species denoted Cu(phenC), and the effect of Cu coverage on the kinetics of electrocatalytic O2 reduction is investigated. At low overpotentials, we observe a 2nd order dependence of the O2-reduction rate on the coverage of Cu(phenC), from which we infer that two physically proximal Cu(phenC) bind O2 to form a binuclear Cu2O2 species required for 4-electron reduction. We suggest that a similar binuclear species also forms in the case of Cu(phenP)8,10 but that rate-limiting binding of O2 to the first Cu(phenP) followed by rapid surface diffusion of a second Cu(phenP) has, until now, obscured the binuclear nature of the reaction.

The covalent attachment of 3-ethynyl-1,10-phenanthroline to an azide-modified glassy carbon electrode to form Cu(phenC) relies on the CuI-catalyzed cycloaddition of azide and ethynyl groups to form a triazole linker, commonly referred to as the click reaction.20,21 The electrode is azide terminated by treating a roughly-ground, heat-treated glassy carbon surface with a solution of IN3 in hexanes, a procedure modified from that first described by Devadoss and Chidsey.22 An XPS survey of the azide-modified surface shows two N 1s peaks at 399 eV and 403 eV in a 2:1 ratio attributable to the azide nitrogens.22-24 Upon exposure to 3-ethynyl-1,10-phenanthroline under the click reaction conditions25, the 403-eV peak disappears and the 399-eV peak broadens, consistent with the formation of the 1,2,3-triazole linker.22,24 XPS peaks at 934 and 953 eV corresponding to the Cu 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 transitions26 and a N-to-Cu coverage ratio of 5.3 ± 0.3 are attributable to a covalently attached Cu(3-(4-triazolyl)-1,10-phenanthroline) complex, Cu(phenC).

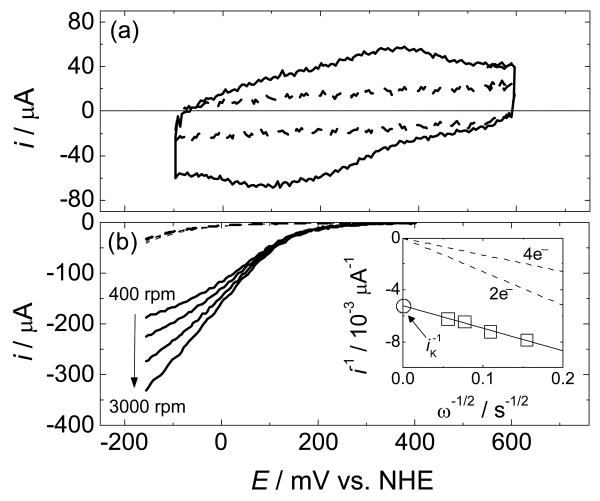

A cyclic voltammogram (CV) of Cu(phenC) on a static glassy carbon electrode shows quasi-reversible reduction and oxidation peaks under anaerobic conditions, which are assigned to the CuII/I redox couple (Figure 1a). The standard redox potential of the complex is taken as the average of the cathodic and anodic peak potentials: vs. NHE.27 The Cu coverage was varied by controlling the initial azide coverage of the glassy carbon electrode,25 and the amount of immobilized Cu catalyst was determined by Faraday's Law from the CuII/I redox charge, Δq. This value was taken to be the average of the absolute values of the integrated current in the negative and positive scans of the CV corrected by the same scans after the surface was stripped of all copper.28 For the CV presented in Figure 1a, Δq = 21.8 μC, which is equivalent to a coverage of 7.0 × 1014 molecules cm-2. The relatively high surface coverage is consistent with significant roughness of the roughly-ground surface.29

Figure 1.

(a) Cyclic voltammogram (CV) of Cu(phenC) on a static glassy carbon electrode in an Ar-purged aqueous solution (scan rate = 1000 mV/s). The dashed line is the same CV repeated after Cu was removed by exposing the surface to a Cu chelating agent for 20 min while rotating the electrode at 3000 rpm. (b) Rotating-disk voltammograms for the reduction of O2 in an O2-saturated aqueous solution by Cu(phenC) (scan rate = 25 mV/s). The dashed lines are the same set of rotating-disk voltammograms repeated after Cu was removed by exposing the surface to a copper-chelating agent for 20 min while rotating the electrode at 3000 rpm. The inset is a Koutecky-Levich plot of the inverse of the disk current measured at 0 mV vs. NHE as a function of square root of the inverse of the rotation rate. The dashed lines are calculated diffusion-limited currents for the reduction of O2 by 2 and 4 electrons. The fitted line yields n = 3.6 electrons. The intercept is the inverse of the kinetically limited current, (iK)-1. All solutions contained 0.05M sodium acetate, 0.05M acetic acid, 1 M sodium perchlorate with measured pH = 4.8.

O2 reduction by Cu(phenC) was measured at a rotating-disk electrode (RDE) at several rotation rates (Figure 1b).30 The currents show an onset of O2 reduction negative of . The currents are independent of the scan rate at or below 25 mV/s (not shown), but increase with increasing rotation rate as shown. In the limit of high rotation rate, the current is expected to asymptotically approach a potential-dependent kinetic current, iK, independent of the rate of mass transfer to the electrode surface and limited only by O2-binding and reduction kinetics. A Koutecky-Levich plot of the inverse of the current as a function of the inverse square root of the rotation rate yields the inverse of the kinetic current, iK-1, as the intercept (Figure 1b, inset).31 The slope of the Koutecky-Levich plot is inversely proportional to the number of electrons, n, by which O2 is reduced.31 The measured slope in Figure 1b yields n = 3.6,32 suggesting preferential catalysis of 4-electron, rather than 2-electron, reduction of O2.

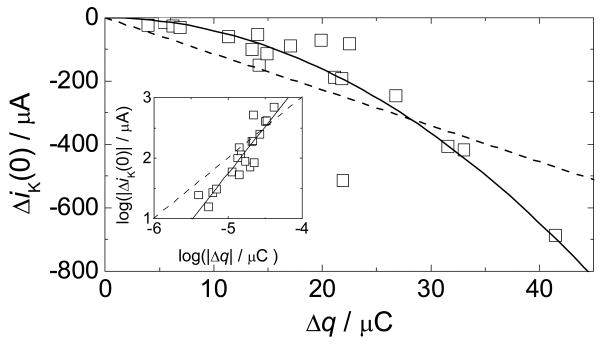

The dependence of the rate of O2 reduction on catalyst coverage was determined from the difference in the measured kinetic currents with and without Cu on the electrode surface, ΔiK. This procedure was chosen to compensate for variable redox charge and kinetic current baselines. A plot of ΔiK as a function of Δq measured at 0 mV vs. NHE shows a 2nd order dependence (Figure 2), confirmed by a log/log plot slope of 1.98 (Figure 2, inset).33

Figure 2.

Difference in kinetic currents for O2 reduction with and without Cu, ΔiK, at 0 mV vs. NHE, for different Cu(phenC) coverages as measured by the redox charge Δq. The solid line is the best fit of the form y = ax2. The dashed line is the best fit of the form y = ax. The inset is a log-log plot of the same data. The solid line in the inset is a linear fit with slope = 1.98. The dashed line has slope = 1 for comparison.

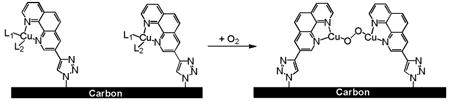

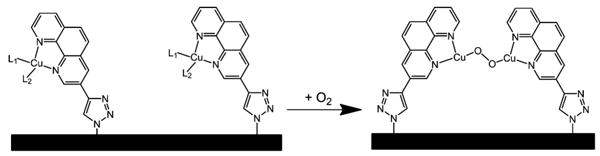

This 2nd order dependence on coverage along with the onset of the O2-reduction current negative of the CuII/I redox potential suggests a potential-dependent rate of reduction of an O2 species ligated by 2 proximal CuI(phenC) sites as presented in Equations 1-3.35 The proximal sites, {2 CuI}, reversibly bind O2 to form {Cu2O2} (Equation 1, Figure 3), followed by a potential-dependent reduction step (Equation 2). Rapid protonation and further reduction regenerate the proximal CuI sites {2 CuI} and release water (Equation 3).36

Figure 3.

The proposed binding event between 2 proximal Cu centers and a single O2 molecule to form a Cu2O2 intermediate species.34

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The potential-dependent rate constant for the reduction of {Cu2O2}, k2(E), can be expanded using the Butler-Volmer parameterization (Equation 4):

| (4) |

where is the standard rate constant of the electron-transfer reaction, F is Faraday's constant, α is the transfer coefficient typically taken to be 0.5, R is the ideal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, and is the standard reduction potential of {Cu2O2}.

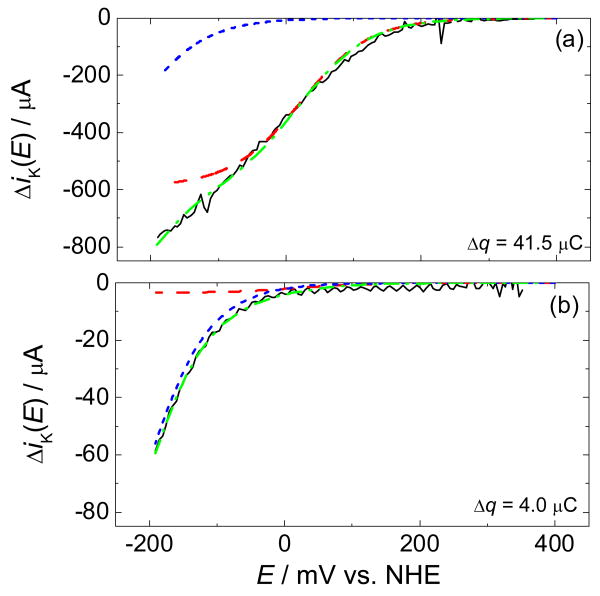

At high Cu coverage, the dependence of ΔiK on potential (Figure 4a, solid) approximates the sigmoidal curve expected for an electrocatalytic process that is limited at high overpotential by a non-electrochemical step such as that in Equation 1.31 The deviation from sigmoidal behavior at more negative potentials suggests an additional O2-reduction pathway at greater overpotential. More striking evidence of this pathway is observed at low Cu coverage (Figure 4b, solid) with an approximately exponential rise in O2 reduction below 0 mV vs. NHE.

Figure 4.

Difference in kinetic currents for O2 reduction with and without Cu, ΔiK, (a) high coverage (Δq = 41.5 μC) and (b) low coverage (Δq = 4.0 μC). The solid black line is the measured ΔiK. The dash-dotted green line is a proposed fit to the data comprised of the sum of the potential-dependent currents from two competing pathways (Equation 8): a binuclear 4-electron O2-reduction pathway (red dashed) and a mononuclear 2-electron O2-reduction pathway (blue dotted).

We propose that the second O2-reduction pathway is due to site-isolated mononuclear Cu complexes, {CuI}, which reduce O2 by 2 electrons and 2 protons to H2O2 at more negative potentials (Equations 5-7). This model is supported by the increased H2O2 production detected in rotating ring-disk voltammetry experiments at high overpotentials.37

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

k2′(E) can be expanded using the Butler-Volmer model in a similar manner as shown in Equation 4. The total kinetic current for 4- and 2-electron reduction of O2 expected by the two pathways is given in Equation 8.25

| (8) |

This model provides a good fit to the observed kinetic currents for O2 reduction by Cu(phenC) at both high and low coverage (Figure 4a-b).

The 2nd order dependence of O2 reduction on the coverage of Cu(phenC), best observed at positive potentials, is distinct from the 1st order dependence on Cu coverage determined by Anson et al. for Cu(phenP) on edge-plane graphite.10 We have confirmed the Anson result at 0 mV vs. NHE,25 and have previously reported that there is no rate-limiting step for electrocatalytic O2 reduction by Cu(phenP) subsequent to O2 binding. 19, 38 In the physisorbed case, the expected high surface lateral mobility of Cu(phenP)39 will ensure that once one Cu(phenP) coordinates O2, another Cu(phenP) will be able to combine rapidly in an unconstrained manner to form a Cu2O2(phenP)2 complex. This would lead to the observed 1st order dependence on the Cu coverage if all reduction and protonation steps beyond the peroxide level intermediate are fast.

In conclusion, controlling the coverage of a covalently attached electrocatalyst allows for detailed mechanistic study of electrocatalytic processes. Here, this method yields evidence that the electrocatalytic 4-electron reduction of O2 to water by adsorbed discrete Cu catalysts requires two proximal CuI sites to coordinate and efficiently reduce O2. A general mechanism is proposed for electrocatalytic O2 reduction by adsorbed Cu catalysts that is consistent with both the observed 2nd order rate dependence on Cu coverage for covalently-immobilized Cu(phen) and the observed 1st order rate dependence on Cu coverage for physisorbed Cu(phen). This study suggests that having a polynuclear assembly is the key to attain 4-electron reduction of O2 at low overpotentials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Stanford Global Climate and Energy Project and an NIH grant (GM-050730). C.C.L.M. also acknowledges financial support for this work from a Ford Foundation Dissertation Fellowship. We acknowledge useful discussions with Robert M. Waymouth, David M. Pearson, Matthew A. Pellow, and Jonathan D. Prange.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental preparation of Cu(phenC) on glassy carbon, the method of Cu removal, and the study of the dependence of O2 reduction on the coverage of Cu(phenP) on edge-plane graphite. This material is available free of charge at http://www.acs.org.

Contributor Information

T. Daniel P. Stack, Email: stack@stanford.edu.

Christopher E. D. Chidsey, Email: chidsey@stanford.edu.

References

- 1.Solomon EI, Sundaram UM, Machonkin TE. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2563–2605. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farver O, Pecht I. In: Multi-Copper Oxygenases. Messerschmidt A, editor. World Scientific; Singapore: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1013–1046. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweiger H, Vayner E, Anderson AB. Electrochem Solid-State Lett. 2005;8:A585–A587. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vayner E, Schweiger H, Anderson AB. J Electroanal Chem. 2007;607:90–100. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Anson FC. J Electroanal Chem. 1992;341:323–341. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zagal JH, Paez C, Aguirre MJ, Garcia AM, Zamudio W. Bol Soc Chil Quim. 1993;38:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Anson FC. Electrochim Acta. 1993;38:2423–2429. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Anson FC. J Electroanal Chem. 1993;348:81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei Y, Anson FC. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:5003–5009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marques ALB, Zhang J, Lever ABP, Pietro WJ. J Electroanal Chem. 1995;392:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Losada J, del Peso I, Beyer L. Inorg Chim Acta. 2001;321:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dias VLN, Fernandes EN, da Silva LMS, Marques EP, Zhang J, Marques ALB. J Power Sources. 2005;142:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng YC, Fan FRF, Bard AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17576–17577. doi: 10.1021/ja054812c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang M, Xu X, Gao J, Jia N, Cheng Y. Russ J Electrochem. 2006;42:878–881. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pichon C, Mialane P, Dolbecq A, Marrot J, Riviere E, Keita B, Nadjo L, Secheresse F. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:5292–5301. doi: 10.1021/ic070313w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermann A, Silva LS, Peixoto CRM, Oliveira ABd, Bordinhão J, Hörner M. Eclet Quim. 2008;33:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorum MS, Yadav J, Gewirth AA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:165–167. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCrory CCL, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP, Chidsey CED. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:12641–12650. doi: 10.1021/jp076106z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tornoe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devadoss A, Chidsey CED. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5370–5371. doi: 10.1021/ja071291f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wollman EW, Kang D, Frisbie CD, Lorkovic IM, Wrighton MS. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4395–4404. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collman JP, Devaraj NK, Eberspacher TPA, Chidsey CED. Langmuir. 2006;22:2457–2464. doi: 10.1021/la052947q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.See supporting information

- 26.Fuggle JC, Martensson N. J Electron Spectrosc Relat Phenom. 1980;21:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 27.This redox potential is ca. 250 mV positive of that reported for Cu(phenP) on edge-plane graphite electrodes under similar solution conditions.19 Although the addition of the electron-withdrawing triazole partially accounts for this potential shift, other factors are likely operative. We suspect secondary ligation by a surface-bonded species such as surface-oxides may contribute to this shift. Unfortunately, 1:1 Cu to phen complexes are not isolable in aqueous solutions, precluding a direct comparison of the redox potentials of discrete homogenous and heterogenized species.

- 28.Cu was removed with 1M sodium diethyldithiocarbamate in MeOH.25

- 29.Similar coverages were determined for covalently-immobilized ethynylferrocene on identically prepared glassy carbon electrodes37 and edge-plane graphite surfaces.22

- 30.Rotating the electrode sweeps dissolved O2 past the disk at a fixed rate, providing for steady-state O2 reduction.

- 31.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2001. pp. 332–357. [Google Scholar]

- 32.For this determination, DO2=1.8 × 10-5 cm2 s-1 is the diffusion constant of O2 in aqueous solutions (Chang P, Wilke CR. J Phys Chem. 1955;59:592–600.), [O2] = 1.1 mM is the concentration of O2 in O2-saturated 1M NaClO4 solutions (Battion R, Rettich TR, Tominga T. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1983;12:163–178.), and ν = 0.009 cm2 s-1 is the kinematic viscosity of the solution.31

- 33.These measurements were made at 0 mV vs. NHE because it is the most positive potential at which a significant kinetic current exists due to O2 reduction at all coverages.

- 34.Although these electrochemical experiments give no information about the nature of the intermediate Cu2O2 species, reactions of other mononuclear CuI complexes with O2 in solution tend to yield side-on or trans-1,2-peroxodicopper(II) complexes.3 We will depict the structure of the proposed Cu2O2 intermediate with the sterically more-permissive trans-1,2-bonded dioxygen moiety.

- 35.For immobilized Cu-sites, 2nd order dependence suggests that 4-electron O2 reduction requires 2 Cu sites in sufficiently close proximity to both coordinate O2. The number of Cu sites with another proximate Cu site is proportional to the product of ΓCu and the fractional occupancy of sites.

- 36.No dependence of the kinetic current on buffer concentration or pH is observed at 0 mV vs. NHE.25 This is evidence that the protonation steps are fast compared to the potential-dependent reduction steps. We arbitrarily assign the slow electron-transfer step to the first reduction of {Cu2O2}, but it could be a later reduction step.

- 37.McCrory, C. C. L.; Devadoss, A.; Ottenwaelder, X.; Nakazawa, J.; Pearson, D. M.; Pellow, M. A.; Lowe, R. D.; Smith, B. J.; Williams, V. O.; Waymouth, R. M.; Stack, T. D. P.; Chidsey, C. E. D. unpublished results.

- 38.Lei and Anson determined O2 binding to be the rate limiting step for Cu(phenP) on edge-plane graphite surfaces at high overpotentials.10 O2 reduction by Cu complexes of other substituted-1,10-phenanthroline ligands exhibit first order behavior in Cu coverage at high overpotential as well,19 but the order with respect to Cu has not been investigated at 0 mV vs. NHE. Some data suggests that O2 binding may not be rate limiting at low overpotentials for more easily-reduced Cu complexes with substituted 1,10-phenanthroline ligands.19

- 39.For example, the translational diffusion coefficients of benzene and hexane on basal-plane graphite surfaces are 1.99 ± 0.06 × 10-5 cm2 s-1 and 3.69 ± 0.11 × 10-5 cm2 s-1, respectively (Fodi B, Hentschke R. Langmuir. 1998;14:429–437.), and the translational diffusion coefficients of anthracene and pyrene on small graphitic grains are 3.05×10-4 cm2 s-1 and 1.0×10-4 cm2 s-1, respectively (Neue G. Lecture Notes in Phys. 1989;331:378–380.). Even at a very low coverage of 1×1012 molecules cm-2 (Δq = 1.95 × 10-8 C, two orders of magnitude lower than the lowest coverage reported in this study), the average distance between a given Cu(phen) and its closest neighbor is only 1×10-6 cm. Assuming a translational diffusion constant of 2 × 10-5 cm2 s-1, the complexes would migrate together on the timescale of 2 × 10-4 s, which is 4 orders of magnitude faster than the measured timescale of a complete O2-reduction event.10,19

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.