Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To establish the psychometric characteristics of a newly developed, brief bilingual 14-item parent report tool (The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale [MCH-Feeding Scale]) designed to identify feeding problems in children six months to six years of age.

METHODS:

To establish construct validity, 198 mothers of children visiting community paediatrician’s offices (normative sample) and 174 mothers of children referred to a feeding clinic (clinical sample) completed the scale. Test-retest reliability was obtained by the re-administration of the MCH-Feeding Scale to 25 children in each sample.

RESULTS:

Excellent construct validity was confirmed when the mean [± SD] scores of the normative and clinical samples were compared (32.65±12.73 versus 60.48±13.04, respectively; P<0.01). Test-retest reliabilities were high for both groups (normative r=0.845, clinical r=0.92).

CONCLUSION:

The MCH-Feeding Scale can be used by paediatricians and other health care professionals for quick identification of feeding problems.

Keywords: Assessment of health care needs, Child, Failure to thrive, Feeding and eating disorders of childhood, Feeding behaviour, Infant

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Établir les caractéristiques psychométriques d’un bref outil bilingue de rapport en 14 points par les parents (l’échelle d’alimentation de L’Hôpital de Montréal pour enfants [échelle d’alimentation-HME]) récemment conçu pour repérer les problèmes alimentaires chez les enfants de six mois à six ans.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Pour établir la validité conceptuelle de l’outil, 198 mères d’enfants ayant consulté au cabinet de pédiatres communautaires (échantillon normatif) et 174 mères d’enfants ayant été aiguillés vers une clinique d’alimentation (échantillon clinique) ont rempli l’échelle. Pour obtenir la fiabilité de test-retest, les chercheurs ont réadministré l’échelle d’alimentation-HME à 25 enfants de chaque échantillon.

RÉSULTATS :

L’excellence de la validité conceptuelle a été confirmée lors de la comparaison des indices moyens (± ÉT) des échantillons normatifs et cliniques (indice moyen de 32,65±12,73 par rapport à 60,48±13,04, respectivement; P<0,01). La fiabilité de test-retest était élevée dans les deux groupes (normatif r=0,845, clinique r=0,92).

CONCLUSION :

L’échelle d’alimentation-HME peut être utilisée par les pédiatres et les autres professionnels de la santé pour déceler rapidement des problèmes alimentaires.

Feeding problems occur in 25% to 50% of healthy infants and toddlers, representing a significant issue in the paediatric population (1–3). Although some feeding problems are relatively common and transient in nature, 3% to 10% of children present with more severe forms of feeding problems that, if left untreated, place them at risk for malnutrition, failure to thrive, and behavioural and developmental disturbances (4,5). Although feeding problems tend to be nonmedical in nature, they may well be the result of medical disorders or interventions that interfere with the normal development of feeding skills. Today, most clinicians agree that feeding problems are biopsychosocial in nature (6) because both physiological and psychosocial factors contribute to their initiation and maintenance. The causes of feeding difficulties may be skill based (oral sensory-motor disorders [7–9]) and/or motivation based (inherent or acquired), which is likely to result in poor weight gain (10–12) and influence the willingness to try new food tastes and textures. These physiological factors tend to trigger altered mealtime behaviours and interactions with parents, which subsequently maintain or increase the severity of feeding problems (8,13).

A number of standardized psychometric tools have been developed over the past 25 years to assess feeding problems. The earlier tools were observational scales of mother-child interactions during a mealtime (14,15), whereas more recent scales such as the Children’s Eating Behaviour Inventory (CEBI [16]), the Behavioral Pediatrics Feeding Assessment Scale (BPFAS [17]), and the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (18) use parental report to assess child mealtime behaviours. The development of both the CEBI and the BPFAS was based on the assumption that both child and parental characteristics contribute to childhood eating and mealtime problems. The CEBI consists of 40 items pertaining to the child and parent behaviours, as well as interactions between family members. For each item, the respondent indicates how often the behaviour occurs on a five-point Likert scale, and whether the item is perceived to be a problem. The scale, applicable to children two to 12 years of age, has good validity and reliability (16). The BPFAS is a 35-item parent report measure of the child’s mealtime behaviours and related parental reactions. The scale includes new items and reworded items from the CEBI. The scale, developed for children nine months to eight years of age, has adequate reliability. More importantly, results of their validity study (19) showed that children with feeding difficulties engage in the same type of feeding behaviours as children in a nonclinical sample, but at an increased frequency.

Although these two scales are reliable and valid tools for the assessment of feeding problems, they do not lend themselves to quick identification of these problems. Paediatricians and other clinicians need access to a valid and reliable instrument that can quickly verify parental complaints about their child’s feeding problems; otherwise, parental complaints may go unnoticed (20,21). Therefore, the purpose of our study was to develop and evaluate a one-page, easily administrable feeding scale that could help clinicians identify feeding problems within a couple of minutes in their offices. In addition, given the bilingual nature of the paediatric population in several hospitals in Canada, the development of a bilingual feeding scale was deemed to be desirable.

METHODS

Participants

The 198 healthy children in the normative sample were recruited from community paediatricians’ offices. Participants for the clinical sample were from a hospital-based multidisciplinary feeding disorders clinic (FDC). These children were referred for feeding problems by their paediatricians or medical speciality clinics of the hospital. Of the 174 children in the clinical group, 91 children without medical problems constituted the clinical nonmedical group. The clinical medical group was comprised of 83 children with associated medical problems (eg, gastroenterological, cardio-respiratory or metabolic/genetic disorders). Tube-fed children were excluded from the study. The age range for both groups was from six months to six years, 11 months.

Measure: Scale construction

Item development and content:

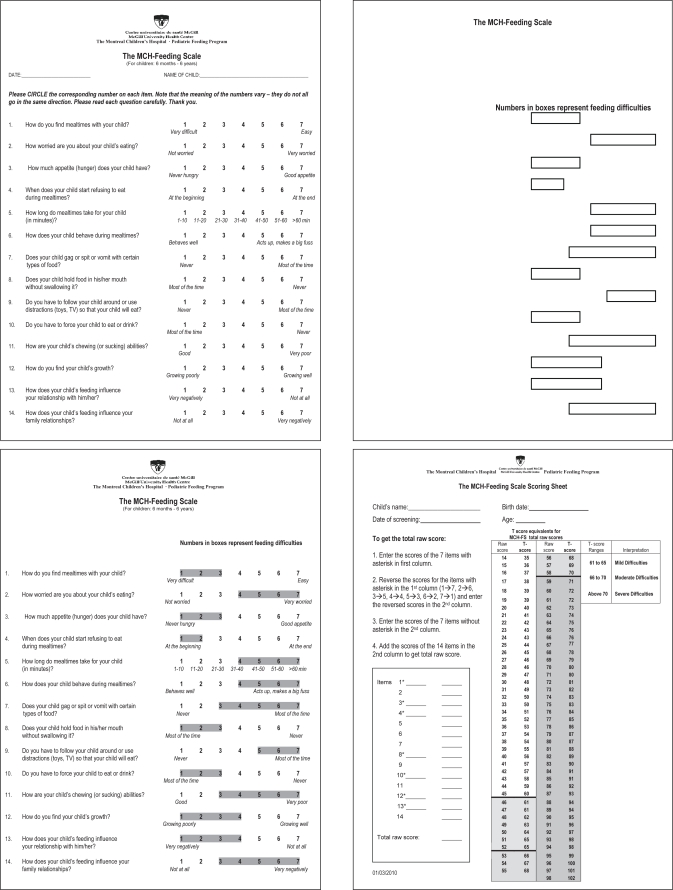

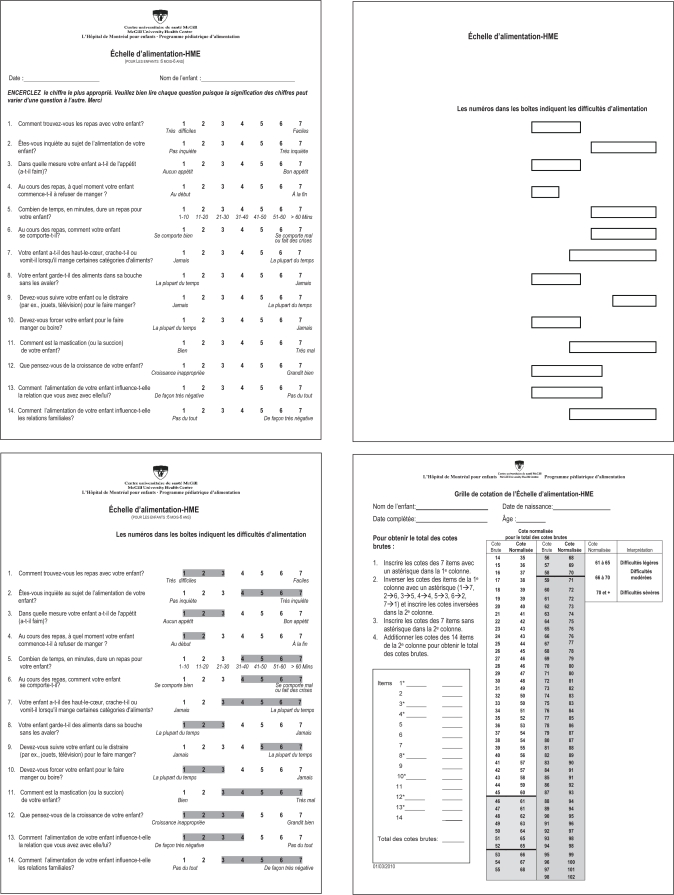

Items for The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (MCH-Feeding Scale; see Appendix 1) were generated over several years by psychologists working with children with feeding disorders. Items were selected according to the biopsychosocial model of feeding problems. The scale targeted children six months to six years of age because children younger than six months of age tended to be exclusively breastfed or bottle-fed. A cut-off age of six years was used because the majority of clinical referrals were for children younger than six years of age, although it was recognized that children older than six years of age would also exhibit similar feeding problems (16). The items chosen were general in nature and covered behaviours applicable to all ages (eg, gags on food textures) rather than age specific (eg, eats with spoon). A pretest of the scale was conducted to verify its utility to identify feeding problems. The scale was translated into French by a professional translator (L’Échelle d’alimentation de L’Hôpital de Montréal pour enfants; see Appendix 2). The sample consisted of 210 children from paediatric offices and 110 children from the FDC. Although good construct validity was obtained for the 15-item scale, some items needed slight rewording and one item was eliminated.

The final scale consisted of 14 items covering the following feeding domains with some overlap: oral motor (items 8 and 11), oral sensory (items 7 and 8) and appetite (items 3 and 4). Other items covered maternal concerns about feeding (items 1, 2 and 12), mealtime behaviours (items 6 and 8), maternal strategies used (items 5, 9 and 10) and family reactions to their child’s feeding (items 13 and 14). After approval by the Institutional Review Board of The Montreal Children’s Hospital (Montreal, Quebec), the data were collected between August 2004 and March 2006.

Item scaling and scoring:

Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale with anchor points at either end. Seven items are scored from the negative to positive direction, and the other seven from the positive to negative direction. The primary feeder marks each item according to frequency or difficulty level of a particular behaviour or the level of parental concern. The total feeding problem score is obtained by adding the scores for each item after reversing the scores of seven items from negative to positive.

The scale takes approximately 5 min to complete, and by using an acetate overlay indicating scores for each item that are clinically significant, it takes approximately 1 min to determine the degree of feeding problems and maternal concerns. If desired, a total score may be obtained in less than 10 min.

Procedure

Normative sample:

A trained research assistant visited the offices of paediatricians in the hospital’s catchment area who agreed to participate in the study, and obtained for that day a list of patients whose files did not indicate major medical problems. The research assistant approached the mothers and invited them to participate in the study. If a mother agreed, she was given a consent form to read and sign, followed by a demographic questionnaire, which included a question about whether the child had any major medical problems. Then, the MCH-Feeding Scale was presented. For the reliability part, every second mother was approached once the scale was completed, and asked to complete the scale on a second occasion within seven to 10 days. Mothers who agreed were provided with a copy of the scale to complete during a telephone call with the research assistant. Of the 38 parents who were asked to participate in the reliability aspect of the study, 25 completed the scale for the second time. Eight declined and five could not be contacted within the required period of time.

Clinical sample:

Mothers whose children are referred for feeding problems to the FDC routinely receive a home package containing the MCH-Feeding Scale and a demographic questionnaire, which they are asked to complete before their first appointment in the clinic. During the study period, 174 consecutive home packages were returned at the time of the first appointment. For the reliability part of the study, every second mother received the home package with a consent form, which explained the purpose of the reliability study. Mothers, contacted seven to 10 days before their first visit to the FDC, were asked about their willingness to participate. Those who agreed were instructed to complete the scale that same day. The scale was completed for a second time on the day of the first appointment. Of the 38 mothers who were asked to participate in the reliability part of the study, all agreed, but only 25 completed the questionnaire at the time contacted. The others either did not complete their questionnaire that day or had to postpone their first appointment to the FDC.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 16; IBM Corporation, USA). Characteristics of the subjects and their parents were compared among normative, clinical nonmedical and clinical medical groups using ANOVA and Pearson’s χ2 tests. To evaluate internal consistency, exploratory factor analyses were performed on the individual items of the scale with principal component analysis using Keiser’s criteria and the Scree test. For construct validity, the total and individual item scores were compared among the normative, clinical nonmedical and clinical medical samples using ANOVA. The discrimination score for identifying feeding problems was set at 1 SD above the mean total score obtained by the normative sample. To evaluate the accuracy of this discrimination score, sensitivity and specificity were calculated, and ROC analysis was performed. Sample size was calculated for ROC analysis. It was hypothesized that the area under the ROC curve would equal 0.9 (95% CI 0.8 to 1.0). To acquire a power of 90% at a significance level of 0.05, a minimum of 68 participants was required for the clinical sample and 136 participants for the normative sample. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for the total scores and individual items of the MCH-Feeding Scale between initial scores and scores obtained seven to 10 days later for test-retest reliability.

RESULTS

Study population

Characteristics of subjects and their parents for the normative and clinical (nonmedical and medical) groups are shown in Table 1. Children in the clinical medical sample had a lower gestational age and birth weight than children in the normative and clinical nonmedical samples. Compared with the other two groups, a higher percentage of the clinical nonmedical sample were first-born children. Although maternal education was significantly different between the normative and clinical groups, in practical terms, six months’ difference in level of education is not meaningful. The types of feeding problems diagnosed in both the clinical nonmedical and clinical medical groups are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Normative (n=198) | Clinical nonmedical (n=91) | Clinical medical (n=83) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | ||||

| Maternal age, years | 34.09±5.52 | 32.98±5.31 | 32.90±5.17 | 0.127 |

| Paternal age, years | 36.38±5.94 | 37.24±6.83 | 36.47±5.65 | 0.538 |

| Maternal education, years | 15.01±2.56 | 14.28±2.77 | 14.26±2.52 | 0.029 |

| Paternal education, years | 14.83±2.68 | 14.85±2.68 | 14.10±2.75 | 0.109 |

| Child | ||||

| Age, months | 31.16±19.62 | 24.64±15.92 | 26.93±17.31 | 0.013 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 38.96±2.27 | 39.03±1.57 | 37.21±3.79 | 0.000 |

| Birth weight, g | 3359±609 | 3130±547 | 2832±917 | 0.000 |

| Boys, n (%) | 92 (46) | 48 (53) | 50 (61) | 0.082 |

| First born, n (%) | 91 (47) | 61 (67) | 37 (46) | 0.005 |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

One-way ANOVAs for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 for categorical variables

TABLE 2.

Types of feeding problems in the clinical sample

| Type of feeding problem | Clinical nonmedical (n=91), n (%) | Clinical medical (n=83), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of motivation | 56 (61.5) | 49 (59.0) |

| Oral-motor deficits | 6 (6.6) | 8 (9.6) |

| Food selectivity by texture | 37 (40.7) | 28 (33.7) |

| Food selectivity by type | 41 (45.1) | 36 (43.4) |

| Total | 140* | 121* |

The total in both groups is higher than the actual number studied because many children had more than one type of feeding problem diagnosed

Internal consistency

The individual items of the MCH-Feeding Scale of the normative sample could be reduced to one factor that accounted for 48% of the variance, suggesting that the total score can be used as a measure of feeding problems. The correlations between the individual items and this one-component model ranged from 0.48 to 0.87.

Construct validity

There were no significant differences between the means for the individual items and mean total scores of the clinical nonmedical sample compared with the clinical medical sample (59.78±13.04 versus 61.17±13.14, respectively). Child characteristics and parent demographics were not significant covariates for mean total scores. After combining the two clinical samples, children in the normative sample obtained significantly lower mean scores for each of the 14 items (P<0.01) as well as for the mean total scores (P<0.01) compared with children in the clinical sample (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Mean total score and individual item scores of The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale for normative and combined clinical groups

| Individual item | Normative (n=198) | Clinical (n=174) |

|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 2.85±1.58 | 5.30±1.53 |

| Item 2 | 2.44±1.58 | 5.49±1.59 |

| Item 3 | 2.64±1.44 | 4.60±1.51 |

| Item 4 | 3.14±2.02 | 5.42±1.67 |

| Item 5 | 2.74±1.12 | 3.57±1.84 |

| Item 6 | 2.72±1.44 | 4.60±1.80 |

| Item 7 | 1.87±1.24 | 4.02±2.04 |

| Item 8 | 2.27±1.58 | 3.55±2.08 |

| Item 9 | 2.72±1.99 | 4.91±2.16 |

| Item 10 | 2.46±1.65 | 4.64±2.04 |

| Item 11 | 1.48±1.03 | 3.32±2.09 |

| Item 12 | 1.70±1.08 | 4.14±2.05 |

| Item 13 | 1.83±1.20 | 3.37±1.89 |

| Item 14 | 1.80±1.29 | 3.56±1.99 |

| Total score* | 32.65±12.73 | 60.48±13.04 |

Data presented as mean ± SD.

All 14 items and the total score differed significantly by group at P<0.01

An ANCOVA was performed, with both age groups (from six to 24 months versus 25 to 83 months) and language of the MCH-Feeding Scale (English versus French) as covariates. There was no significant difference in the total scores between younger and older children, or between scales completed in English and French (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale: Total scores for normative and combined clinical groups by age and language

| Independent variables |

Normative (n=198) |

Clinical (n=174) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Score, mean ± SD | n | Score, mean ± SD | |

| Age, months | ||||

| 6 to 24 | 97 | 31.12±13.14 | 100 | 59.80±13.60 |

| 25 to 83 | 101 | 34.11±12.21 | 74 | 61.42±12.30 |

| Language | ||||

| English | 41 | 33.19±12.33 | 111 | 61.44±13.00 |

| French | 57 | 31.32±13.69 | 63 | 58.81±13.06 |

A total score of 45, which is 1 SD above the mean obtained by the normative sample on the MCH-Feeding Scale, was used as the discrimination score for identifying feeding problems. When using a total score of 45 as the discrimination score, the results demonstrated excellent sensitivity (87.3%) and specificity (82.3%). The area under the ROC curve was 0.845, suggesting good accuracy for this discrimination score.

Test-retest reliability

For the total score of the MCH-Feeding Scale, the correlation coefficients were 0.85 for the normative and 0.92 for the clinical sample at P<0.01 (two-tailed), indicating a high level of stability for the total score of the scale. Correlation coefficients for the individual items ranged from 0.76 to 0.98 in the normative sample and from 0.69 to 0.97 in the clinical sample, indicating an acceptable level of stability for the individual items. All correlations for the individual items were significant at P<0.01 (two-tailed).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the development of a valid and reliable bilingual screening tool for quick detection of feeding problems in children from six months to six years of age was presented. Except for child age, no attempt was made to match child and parental variables for the normative and clinical groups. Nonetheless, the parental demographic data were similar in the three groups (normative, clinical nonmedical and clinical medical), suggesting that our normative sample was well matched to our clinical samples in terms of these variables. Although gestational age, birth weight and birth order were significantly different for the normative and two clinical groups, these variables did not influence the mothers’ report of feeding problems, implying that feeding difficulties cut across demographic variables and children’s health status, lending further support to the more recent biopsychosocial perspective of feeding problems (6,20). Although the four types of feeding problems (lack of motivation, oral-motor deficits, food selectivity according to texture and food selectivity according to taste) were diagnosed in both the clinical nonmedical and clinical medical groups, the severity of feeding problems likely varied according to their medical problems or pathophysiology (6,7,9).

The mean total score on the MCH-Feeding Scale for the clinical group was more than 2 SDs higher than that of the normative sample, confirming the construct validity of this scale. Further support for construct validity came from the findings that there was no difference in the total MCH-Feeding Scale scores between the younger and older children as well as between the French and English versions, either between groups or within groups.

Of note is that parents in the normative group also reported difficulties around mealtimes, indicating that some degree of a feeding problem is part of typical feeding development and mealtime behaviours. However, the clinical and normative groups were clearly different with regard to parental perception of the severity and/or frequency of feeding difficulties and their reactions to them. These findings replicate those of Crist and Napier-Phillips (19), who found that children with feeding problems engage in the same types of feeding behaviours as children without feeding difficulties, but at a higher frequency. In addition, the two clinical groups had almost identical scores on every item and total scores, suggesting that the parents of both clinical groups perceived similarly high frequency or intensity of mealtime behaviours and parental reactions, independent of medical issues. These results lend support to the notion that feeding disorders should be considered as a separate clinical entity requiring clinics specialized in feeding disorders.

Good sensitivity and selectivity of the scale were confirmed with a cut-off point of 45, suggesting that with this cut-off point, the scale should give a low rate of misdiagnosis of feeding problems. One caveat is that, although our assessment confirmed the diagnosis of feeding problems in the clinical sample, the normative sample was not assessed and, thus, children with feeding disorders could not be excluded. However, given the literature on feeding problems in the general paediatric population, it was expected that a certain percentage of mothers would report feeding problems. In our normative sample, 17.5% of children had total scores on the MCH-Feeding Scale 1 SD above the mean and 4.5% had total scores 2 SDs above the mean. These percentages are similar to findings of larger-scale studies in which approximately 25% to 50% of children were reported to have feeding difficulties and, of these, 3% to 10% were reported to be severe (1,2,4,5). These results further confirm the need for a short and easily administrable tool that would allow quick identification of feeding difficulties and mealtime struggles. With good internal consistency and reliability measures, the brief scale in the present report fulfills this need.

One limitation of the present study is that parents who agreed to participate may have differed from the general population because we did not record the number of parents who declined participation. The other possible limitation relates to the reliability study. Mothers in the clinical sample were aware that they would be asked to complete the scale on a second occasion before completing the MCH-Feeding Scale for the first time. However, in the normative group they completed the scale for the first time, unaware that they would be asked to complete the scale for a second time. Although it was believed that forewarning the clinical group would inflate their reliability scores, the results did not support this hypothesis because the total scale and individual item reliability correlations for the two groups were very similar.

CONCLUSION

The MCH-Feeding Scale compares favourably with the longer behavioural and unilingual feeding scales by Archer et al (16), Crist et al (17), and Crist and Napier-Phillips (19) in terms of construct validity and reliability. This one-page scale enables the rapid identification of feeding difficulties in clinicians’ offices. Regardless of whether they struggle with medical issues, the identification of these children is important because they deserve expert clinical attention. Unique aspects of the MCH-Feeding Scale are that it is bilingual and can be used for quick detection of feeding problems with the help of an acetate overlay.

The MCH-Feeding Scale, scoring package and template for the acetate page are available in both languages in Appendix 1 (page e16) and Appendix 2 (page e17).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the children and their parents for participating in this study. The work originated at The Montreal Children’s Hospital. This research was supported by the Research Institute, The Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre in Montreal.

APPENDIX 1.

APPENDIX 2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carruth BR, Skinner JD. Feeding behaviors and other motor development in healthy children (2–24 months) J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:88–96. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDermott BM, Mamun AA, Najman JM, Williams GM, O’Callaghan MJ, Bor W. Preschool children perceived by mothers as irregular eaters: Physical and psychosocial predictors from a birth cohort study. JDBP. 2008;29:197–205. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318163c388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reau NR, Senturia YD, Lebailly SA, Christoffel KK. Infant and toddler feeding patterns and problems: Normative data and a new direction. JDBP. 1996;17:149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbett SS, Drewett RF. To what extent is failure to thrive in infancy associated with poorer cognitive development? A review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:641–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linscheid TR, Budd K, Rasnake LK. Pediatric feeding problems. In: Roberts MC, editor. Handbook of Paediatric Psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 481–98. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rommel N, De Meyer A, Feenstra L, Veereman-Wauters G. The complexity of feeding problems in 700 infants and young children presenting to a tertiary care institution. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:75–84. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anliker JA, Bartoshuk L, Ferris AM, Hooks LD. Children’s food preferences and genetic sensitivity to the bitter taste of 6-n propylthiouracil (PROP) Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:316–20. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field D, Garland M, Williams K. Correlates of specific childhood feeding problems. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer MM, Heyman MB. Assessment and treatment of sensory-versus motor-based feeding problems in very young children. Infants Young Child. 1993;6:168–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsay M, Gisel EG, Boutry M. Non-organic failure to thrive: Growth failure secondary to feeding-skills disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35:285–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1993.tb11640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannenbaum GS, Ramsay M, Martel C, et al. Elevated circulating acylated and total ghrelin concentrations along with reduced appetite scores in infants with failure to thrive. Pediatric Research. 2009;65:569–73. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181a0ce66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Drewett RF. How does maternal and child feeding behavior relate to weight gain and failure to thrive? Data from a prospective birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1262–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsay M, Zelazo PR. Food refusal in failure to thrive infants: Nasogastric feeding combined with interactive behavioral treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 1988;13:329–47. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/13.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnard K, Eyres S, Lobo M, Snyder C. An ecological paradigm for assessment and intervention. In: Brazelton TB, Lester BM, editors. New Approaches to Developmental Screening of Infants. New York: Elsevier; 1983. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatoor I, Schafer S, Dickson L, Egan J, Conners CK, Leong N. Pediatric assessment of nonorganic failure-to-thrive. Pediatr Ann. 1984;13:844–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer LA, Rosenbaum PL, Streiner DL. The children’s eating behavior inventory: Reliability and validity results. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:629–42. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crist W, McDonnell P, Beck M, Gillespie CT, Barrett P, Mathews J. Behavior at mealtime and nutritional intake in the young child with cystic fibrosis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15:157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wardle J, Guthrie C, Sanderson S, Rapoport L. Development of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:963–70. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crist W, Napier-Phillips A. Mealtime behaviours of young children: A comparison of normative and clinical data. JDBP. 2001;22:279–86. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linscheid TR. Eating problems in children. In: Walker CE, Roberts MC, editors. Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 616–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramsay M. Feeding disorders and failure to thrive. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1995;4:605–16. [Google Scholar]