Abstract

Recombinant glycosylated biotherapeutic agents are usually produced in non-human mammalian cell lines, which can synthesize and/or metabolically incorporate the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). This contamination was previously known but ignored, as normal humans were thought to not react against Neu5Gc. However, recent findings indicate that humans have variable spectra of sometimes high levels of circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies. We studied two monoclonal antibodies in clinical use (Cetuximab and Panitumumab), and show covalently-bound Neu5Gc on Cetuximab. Anti-Neu5Gc antibodies from normal humans interact with Cetuximab in a Neu5Gc-specific manner and generate immune complexes in vitro. Mice with a human-like defect in Neu5Gc synthesis generate anti-Neu5Gc antibodies upon injection with Cetuximab. Circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies enhance Cetuximab clearance. These findings have potential relevance to half-life, efficacy and immune reactions in patients given such drugs. Finally, we show a method to reduce the Neu5Gc content of cultured cell lines and their secreted glycoproteins.

Targeted therapies with bioactive glycoproteins now generate sales with annual double-digit growth1. These glycosylated biotherapeutics (antibodies, growth factors, cytokines, hormones and clotting factors etc.) often need to be produced in mammalian expression systems, because the location, number, and structure of N-glycans can influence yield, bioactivity, solubility, stability against proteolysis, immunogenicity and clearance rate2-4.

Rodent cell lines used to produce glycosylated biotherapeutics generate N-glycans similar to those of humans, with two major exceptions. First, humans are genetically deficient in biosynthesizing terminal Galα1-3Gal (“alpha-Gal”) on N-glycans, and spontaneously express antibodies against this structure5. The second example is the non-human sialic acid (Sia) N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). The CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) gene responsible for CMP-Neu5Gc production from CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-Neu5Ac) is irreversibly mutated in all humans6, but intact in non-human mammalian cells used to produce glycosylated biotherapeutics. Furthermore, Neu5Gc can be taken up from animal products present in the culture medium and then metabolically incorporated into secreted glycoproteins7. Thus, even human cells cultured with animal-derived supplements will secrete glycoproteins bearing Neu5Gc.

While Neu5Gc contamination of glycosylated biotherapeutics was already known8,9, it was presumed unimportant, as normal humans were thought to not react to Neu5Gc9. However, the original assays used to detect anti-Neu5Gc antibodies had many limitations, including the fact that only a small number of possible Neu5Gc-containing epitopes were tested. In fact, all humans are now known to have circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies10, sometimes at high levels11. Also, early products like erythropoietin were injected into patients in very small quantities, and had low levels of Neu5Gc8. Nowadays, some biotherapeutics are administered in high milligram quantities per dose, over long periods of time. Indeed, recent reviews on this topic have noted the potential significance of Neu5Gc contamination3,4, and some biopharma companies are actively exploring steps to reduce this contamination12.

Given the use of non-human cell lines and/or animal serum or serum-derived factors, it is likely that recombinant therapeutic glycoproteins carry varying amounts of Neu5Gc. However, given the diversity of products, it is difficult to make generalizations. Thus, we chose to compare two FDA-approved antibodies with the same therapeutic target, the EGF receptor: Erbitux® (Cetuximab, obtained from the UCSD Pharmacy), a chimeric antibody produced in mouse myeloma cells13,14, and Vectibix® (Panitumumab, obtained from Amgen), a fully human antibody produced in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells (CHO cells)15. The samples studied were preparations that would normally be administered to patients.

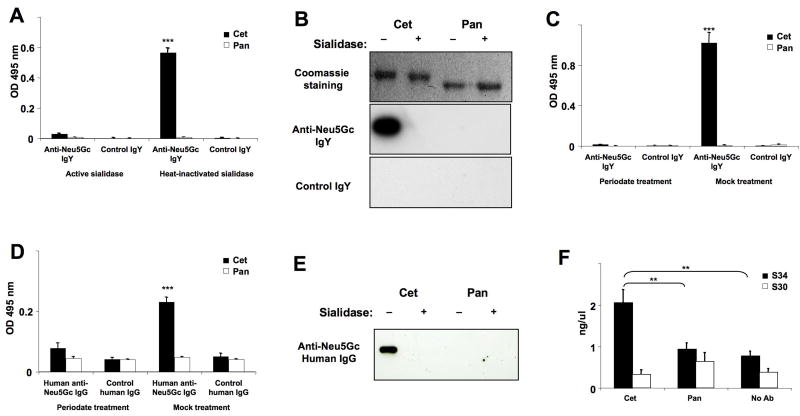

We first did ELISA assays using an affinity-purified polyclonal chicken anti-Neu5Gc antibody preparation that is highly mono-specific for Neu5Gc16, alongside a non-reactive control IgY. Bound Neu5Gc was easily detectable on Cetuximab, and not on Panitumumab (Figure 1A), and sialidase pretreatment abolished binding, confirming specificity. Western Blot analysis also showed anti-Neu5Gc IgY reactivity on the Cetuximab heavy chain, but not on Panitumumab (Figure 1B). Sia-specificity of anti-Neu5Gc IgY binding was reaffirmed by pre-treatment with mild sodium periodate, under conditions that selectively cleave Sia side chains (Figure 1C), and abolish reactivity of such antibodies10,16. Finally, we quantified Sias on the therapeutic antibodies (TAbs), as described in Methods. Panitumumab carries 0.22 mol/mol of Sias, with <0.1% Neu5Gc. In contrast, Cetuximab carries 1.84 mol/mol of Sias, mostly as Neu5Gc (see Supplementary Table 1). The differences likely reflect different cell expression systems. For example, in contrast to CHO cells, murine myeloma cell lines express a greater proportion of Neu5Gc17 (see Supplementary Tables 2-4 for a listing of potential examples). Pull-down assays of Cetuximab with SNA-Agarose (a lectin recognizing α2-6-linked Sias), followed by ELISA of unbound proteins showed that only about half of Cetuximab molecules actually carry bound Sias and Neu5Gc (data not shown). Such heterogeneity is typical for glycoproteins.

Figure 1. ELISA and Western-Blot Detection of Neu5Gc on Biotherapeutic Antibodies by Anti-Neu5Gc IgY Antibodies from Chickens or IgG Antibodies from Normal Human Serum.

Cetuximab (Cet) and Panitumumab (Pan) were treated with active sialidase to eliminate Sia epitopes or with heat-inactivated sialidase as control. Samples were used for ELISA (A) or Western Blot (B), in which Neu5Gc was detected using an affinity-purified chicken anti-Neu5Gc IgY or control IgY. In an additional ELISA (C), Cet and Pan were used for coating, then blocked, and sialic acid epitopes eliminated chemically using sodium metaperiodate. The reaction was stopped with sodium borohydride. As a control, periodate and borohydride were pre-mixed and then added to the wells (the borohydride inactivates the periodate). ELISA samples were studied at least in triplicate and data shown are Mean +/- SD. ***p <0.001, Paired Two-tailed t-test. (D) Cet and Pan were treated with sialidase or heat-inactivated sialidase as in Figure 1A and used for coating ELISA wells, then blocked and incubated with human anti-Neu5Gc IgG that had been purified from the serum of healthy humans and biotinylated. Samples were studied in triplicate and data shown as Mean +/- SD. ***p <0.001 (E) Cet and Pan (1 μg each) were separated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie stained or blotted (see Figure 1B). Neu5Gc content was detected by using biotinylated human anti-Neu5Gc IgG. (F) Immune complex formation with Cet or Pan in whole human serum was detected using the CIC (C1Q) ELISA Kit (Buehlmann) as described in the manufacturer's guidelines. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm. Samples were studied in triplicate and data are shown as Mean +/- SD. **p <0.01, Paired Two-tailed t-test. Gels in Panels B and E were cropped for clarity of presentation. Full-length blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Figures 1-4.

Contrary to prior literature9, serum from healthy humans can contain large amounts of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies10,11. To address potential significance, anti-Neu5Gc antibodies from normal human sera were affinity-purified as described11, biotinylated and used in ELISA and Western Blotting approaches (Figure 1 D-E). As with chicken IgY, these affinity-purified human anti-Neu5Gc antibodies reacted with Cetuximab, but not with Panitumumab. Again, reactivity was abrogated by sialidase pretreatment (Figure 1D) or mild sodium periodate (Figure 1E).

To further address potential clinical relevance, we studied immune complex formation (Figure 1F). Cetuximab formed immune complexes in a human serum with high levels of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies (serum S34, from reference 11), and not with the low titer serum (serum S30, from reference 11). In contrast, Panitumumab gave no detectable immune complex formation with either sera. Assuming that similar interactions do occur between Cetuximab and circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in humans, these complexes could potentially fix complement and cause untoward reactions in some patients, possibly explaining some reported clinical differences13,15.

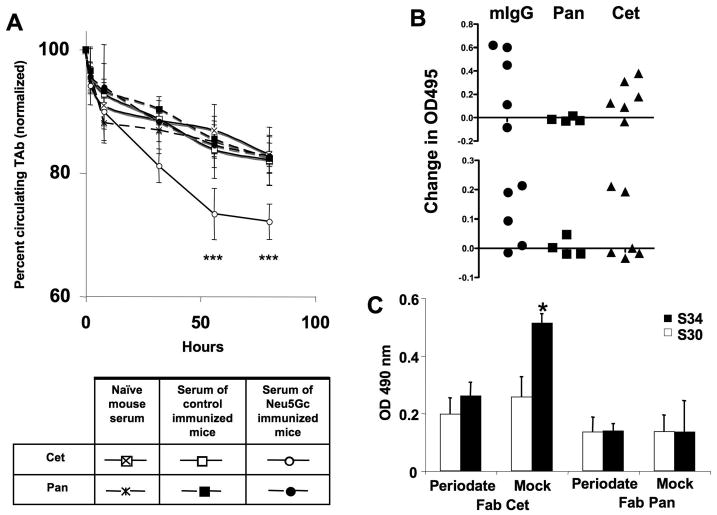

We next evaluated whether Neu5Gc affects clearance rate when circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies are present. To mimic the human situation, we used mice with a human-like defect in the Cmah gene, which encodes the enzyme that generates activated Neu5Gc (CMP-Neu5Gc)18. Such mice can make anti-Neu5Gc antibodies upon immunization with glycosidically-bound but not free Neu5Gc19,20. However, these previous studies used whole rodent or chimpanzee cells for immunization, an obviously artificial approach. On the other hand feeding of Neu5Gc (which is present in mouse chow) does not induce a human-like immune response in the mutant mice21. We obviously could not immunize the mice with Cetuximab itself, as other antibodies directed against the partly human IgG protein backbone would confound any results. To most closely mimic the human situation we therefore immunized with a Neu5Gc-loaded microbe (see Methods, this is very similar to the mechanism by which human anti-Neu5Gc antibodies seem to be naturally generated21). Given the high variability in isotypes and affinities of the naturally-occurring human anti-Neu5Gc antibodies, as well as different relative reactivities against various Neu5Gc-containing antigens11, it is impractical to model all possible human conditions. We therefore chose to mimic a situation in a human with relatively high levels of the IgG antibodies against the kind of Neu5Gc epitope (Neu5Gcα2-6Galβ1-4Glc-) found in Cetuximab22. It also happens that these are epitopes against which human antibodies are common11.

The drugs were injected i.v., aiming for a concentration of 1 μg/ml in extracellular fluid volume (ECF) according to mouse body weight23. Next, sera pooled from naïve, control immunized or Neu5Gc-immunized syngeneic mice were passively transferred via intraperitoneal injection, ensuring equal starting concentrations of circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies. Anti-Neu5Gc IgG levels in the pooled sera from Neu5Gc-immunized mice were quantified by ELISA with a Neu5Gcα2-6Galβ1-4Glc-conjugate as a target, as previously described11 (97.5 μg/ml, data not shown). The amount of pooled antibody injected was then calculated to achieve an approximate starting concentration of 4 μg/ml IgG in the ECF of these mice, i.e. ∼4 times excess of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies compared to the drug in mice, and similar to levels found in some humans11.

Clearance was monitored by a sandwich ELISA specific for human IgG-Fc. While both drugs had a similar clearance rate in mice pre-injected with serum from naïve or control immunized mice, Cetuximab showed a significant decrease in circulating levels when anti-Neu5Gc antibodies were pre-injected (Figure 2A). Assuming a similar interaction between Cetuximab and circulating anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in patients, there could be relevant effects on clearance rate and efficacy. This might help explain the wide range of half-life values reported for such antibodies in clinical studies14,15.

Figure 2. Effects of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies on the kinetics of therapeutic antibodies in mice with a human-like Neu5Gc-deficiency, levels of anti-Neu5Gc IgG in mice after injections of the therapeutic antibodies, and binding of IgG anti-Neu5Gc antibodies from whole human serum to Neu5Gc on the Fab fragment of Cetuximab.

(A) Cmah null mice were first injected i.v. with the therapeutic antibodies (TAbs), namely Cetuximab (Cet) or Panitumumab (Pan), and mouse serum from Cmah null mice containing anti-Neu5Gc antibodies (or serum from naïve mice or control immunized mice) was then passively transferred by IP injection. Mice were bled periodically after the passive transfer of mouse serum. Concentration of Cet and Pan in the isolated sera was determined by Sandwich ELISA. Absorbance was measured at 495 nm. The Y axis starts at 60%, in order to better display the difference in kinetics. ***p <0.001, Unpaired Two-tailed t-test. (B) Cmah null mice were injected i.v. with Cet or Pan weekly and were bled initially, and after the 3rd i.v. injection. In order to detect Neu5Gc specific antibodies by ELISA, wells were coated with human (Neu5Gc-deficient) and chimpanzee (Neu5Gc-positive) serum glycoproteins (Upper Panel), or alternatively with human or bovine fibrinogen (Lower Panel). Data were obtained in triplicate. (C) Fab fragments of Cet and Pan were isolated using the Pierce® Fab Preparation Kit according to the manufacturer's manual. Fab fragments (1 μg/well) were used as target molecules in ELISA. Sialic acid specific binding was determined with sodium metaperiodate treatment. Wells were then blocked and incubated with human sera (S30 and S34 with low and high anti-Neu5Gc IgG titers, respectively, from Ref. 11). Binding of human IgG was detected by using anti-human IgG-Fc. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm and ELISA samples were studied in triplicate. *= p <0.05. Paired Two-tailed t-test.

To further simulate the clinical situation, equal amounts of Cetuximab or Panitumumab were i.v. injected weekly into Neu5Gc-deficient Cmah -/- mice in typical human dosages (4 μg/g body weight). To exclude any impact of the partly (Cetuximab) or fully human protein portion (Panitumumab) in mice, murine IgG was also injected as a positive control, as it happens to carry primarily Neu5Gc (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, Cetuximab and murine IgG (but never Panitumumab) induced a Neu5Gc-specific IgG immune response (Figure 2B, as with humans, responses of individual mice varied greatly, and more positive signals were obtained with the Neu5Gc epitope mixture found in chimp serum). Thus, even patients without pre-existing high levels of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies may be at risk of developing them following injection of Neu5Gc-carrying agents, potentially affecting the outcome of subsequent injections. Also repeated injections of Neu5Gc-carrying agents could load up human tissues with this non-human sugar. In this regard, it is important to note that tissue Neu5Gc accumulation can together with anti-Neu5Gc antibodies mediate chronic inflammation and potentially facilitate progression of diseases such as cancer19 and atherosclerosis24. Thus, chronic use of Neu5Gc-bearing therapeutics might increase future risk of such diseases.

Finally, we also studied direct binding of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies from whole human sera to the biotherapeutic agents. To avoid excessive cross-reactivity involving the secondary reagent, we made Fab fragments of the agents, applied them to ELISA wells, exposed them to human sera, and then detected antibody binding with an anti-human IgG-Fc-specific secondary antibody (note that Cetuximab is known to have an additional glycosylation site in the V-region21). Indeed, we detected mild periodate sensitive binding of serum IgG from a high anti-Neu5Gc titer serum (S34 from Ref. 11, which had >15 μg/ml of IgG antibodies against Neu5Gcα2-6Galβ1-4Glc-), to the Fab fragments of Cetuximab and not to those of Panitumumab (Figure 2C). In contrast, incubation with another human serum containing very low Neu5Gc-antibodies (serum S30 from Ref 11, which had <2 μg/ml of IgG antibodies against Neu5Gcα2-6Galβ1-4Glc-) did not show much periodate-sensitive binding (Figure 2C). Thus, whole human sera with high (but not low) titers of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies showed sialic acid dependent (mild periodate sensitive) binding of serum IgG to Cetuximab, but not to Panitumumab.

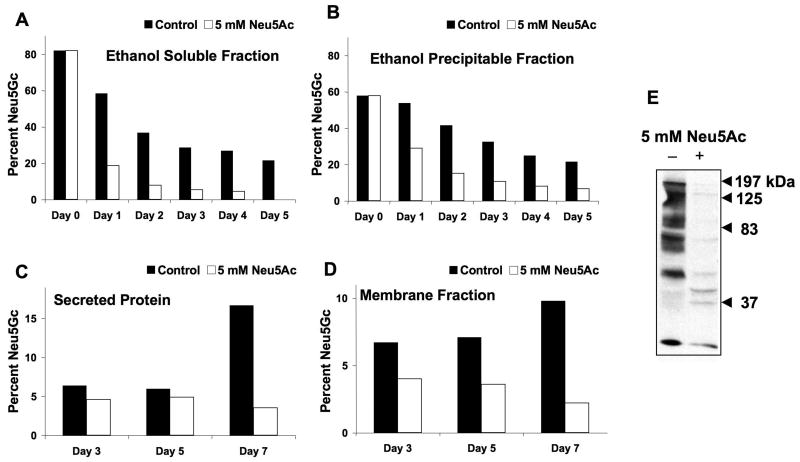

Assuming that our in vitro and in vivo data translate into clinically relevant difficulties for some patients given Neu5Gc-containing biotherapeutics, how can one prevent this problem? Even biotherapeutics produced in human cell lines can be contaminated with Neu5Gc incorporated from animal-derived materials. Furthermore, it is difficult to change from the well-established and FDA-approved cell lines currently in use. Also, Neu5Gc in cells is “recycled” in lysosomes, and reutilized7. We hypothesized that free Neu5Ac in the medium would be taken up and compete with pre-existing Neu5Gc, preventing such recycling. Also, excess Neu5Ac would compete with any further incorporation of medium Neu5Gc7. Thus, we pre-loaded human 293T cells with Neu5Gc, and then chased in the presence or absence of 5 mM Neu5Ac. Such Neu5Ac addition indeed resulted in more rapid disappearance of ethanol-precipitable (glycosidically-bound) Neu5Gc from the cells and also from secreted glycoproteins (Figure 3A-B). Thus, Neu5Ac addition to the medium is a simple and non-toxic way to eliminate or reduce Neu5Gc contamination of human cells, which is now being used in the production of biotherapeutic agents e.g., Xigris® from Eli Lilly and Elaprase® from Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Figure 3. An approach to reduce Neu5Gc Contamination in Biotherapeutic Products.

(A-B) Human 293T cells were grown in the presence of 5 mM Neu5Gc for 3 days. The cells were then washed with PBS, split into two identical cultures, and 5 mM Neu5Ac was added to one of the cultures as shown on the graph. Cells were harvested as described in Methods, and the Neu5Gc and Neu5Ac content of both the ethanol soluble (A) and ethanol precipitable proteins (B) was analyzed by HPLC. The percent Neu5Gc shown is the amount of Neu5Gc relative to the total sialic acids.

(C-E) Feeding of CHO cells with free Neu5Ac reduced Neu5Gc in the whole cell membranes and in secreted glycoproteins. Stably transfected CHO-KI cells expressing a recombinant soluble IgG-Fc fusion protein were grown in the absence or presence of 5 mM Neu5Ac. The individually collected media was centrifuged to remove cell debris and adjusted to 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 8. The fusion protein was purified using Protein-A Sepharose. (C) Sialic acid content was determined by DMB-HPLC analysis as described in Methods. The area under each peak was obtained and the percent of Neu5Gc in each sample was determined relative to Neu5Ac. (D) Total cell membranes from the same CHO cells were prepared and used for DMB-HPLC analysis. (E) CHO membrane proteins from the above experiments were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The expression of Neu5Gc was detected by incubating with polyclonal affinity purified chicken anti-Neu5Gc antibody, as described under Methods. This panel shows a blot of the full-length gel of the two relevant lanes.

However, many recombinant biotherapeutic glycoproteins are currently produced in non-human cells, e.g., CHO cell lines. It is already known that biotherapeutic glycoproteins produced in CHO cells carry small amounts of Neu5Gc8,16. We next asked whether feeding Neu5Ac could reduce Neu5Gc in CHO cells. This was also successful, both for membrane glycoproteins and for a secreted recombinant protein (Figure 3 C-E). Similar feeding of murine myeloma cells with Neu5Ac did not significantly reduce the higher initial Neu5Gc content (∼70–80% of Sias). This is likely because baseline Cmah levels in these cells are high. Regardless, given that the CHO cell expresses its own Cmah enzyme, these data suggest a novel mechanism, in addition to competing out recycled Neu5Gc. Whatever that mechanism, reduction of Neu5Gc content of a recombinant glycoprotein can be achieved even in a non-human Cmah-positive cell line that starts with low levels of Neu5Gc.

Therapeutic glycoproteins have improved many diseases. However, infusion-related reactions and immunogenicity against the agents are concerns3,25. The incidence and severity of an immune reaction depends on the interplay of infused agents with the immune system and can vary greatly from patient to patient. Understanding the underlying nature of these events will help identify patients at risk by specific markers. To reduce immunogenicity, humanized or fully human antibodies have been developed1. However, the potential immunogenicity of the glycans was less considered. It is known that immune reactions can be mediated by binding of pre-existing IgE's against the non-human alpha-gal epitope carried by some agents, such as Cetuximab13 (in our current studies, alpha-gal residues are not an issue, as Cmah null mice already express this sequence, and do not have antibodies against it).

Finally, there is precedent for pre-existing antibodies against a glycan on a glycoprotein secondarily enhancing antibody reactivity against the underlying protein backbone26, perhaps because immune complexes are cleared efficiently by Fc receptors into dendritic cells and other antigen-presenting cells27,28. Such a mechanism might help explain some as yet poorly understood increased immunogenicity to glycoprotein therapeutics in patients over time26,29,30. If this is true, it would likely have a bigger impact in long-term replacement therapy with recombinant therapeutic glycoproteins.

Overall, we suggest that the potential significance of the presence of Neu5Gc on glycoprotein biotherapeutics should be revisited. While a natural tendency is to downplay potential new problems involving currently useful drugs, it is worthwhile considering lessons from other fields, where initial enthusiasm was not balanced by full appreciation of immune risks31. In this regard, we have also suggested that Neu5Gc contamination of stem cells and other cell types intended for human therapy could pose risks32,33. Also, others have recently reported that Cmah null mice can reject Neu5Gc-positive wild-type organ transplants via complement-fixing anti-Neu5Gc antibodies20.

For new drugs, it may be possible to avoid Neu5Gc contamination from the outset, by using Neu5Gc-deficient cells and media. Meanwhile, as an immediate practical solution, we have also shown a non-toxic way to reduce the Neu5Gc content of some currently used expression systems and their secreted glycoproteins, by simply adding Neu5Ac to the culture media. This could bypass the need for establishing new Neu5Gc-deficient cell lines for already approved drugs made in some cell lines. The addition of Neu5Ac to the media could also potentially increase total sialylation of a glycoprotein biotherapeutic agent. But if anything, such addition would only be beneficial, e.g., leading to a longer half-life of the agent in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01-GM32373 and R01-CA38701 to A.V., and ISEF for V.P-K.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors helped design the studies; D.G. and S.D. performed the research; R.T. and V.P-K. generated critical reagents; D.G. and A.V. wrote the paper, and all authors read the paper.

Competing Financial Interest. None of the authors has a personal financial interest in any of the companies whose products are mentioned. A.V. is a co-founder of, and shareholder in Sialix, Inc. (formerly Gc-Free, Inc.), a startup biotech company focused on solving problems arising from Neu5Gc contamination of foods and drugs. D.G. is currently an employee of Sialix, Inc.

References

- 1.Aggarwal S. What's fueling the biotech engine-2007. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1227–1233. doi: 10.1038/nbt1108-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Sim RB, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:21–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durocher Y, Butler M. Expression systems for therapeutic glycoprotein production. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins E. Carbohydrate analysis throughout the development of a protein therapeutic. Glycoconj J. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10719-009-9261-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galili U. Immune response, accommodation, and tolerance to transplantation carbohydrate antigens. Transplantation. 2004;78:1093–1098. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000142673.32394.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varki A. Glycan-based interactions involving vertebrate sialic-acid-recognizing proteins. Nature. 2007;446:1023–1029. doi: 10.1038/nature05816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardor M, Nguyen DH, Diaz S, Varki A. Mechanism of uptake and incorporation of the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid into human cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4228–4237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hokke CH, et al. Sialylated carbohydrate chains of recombinant human glycoproteins expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells contain traces of N-glycolylneuraminic acid. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81427-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noguchi A, Mukuria CJ, Suzuki E, Naiki M. Failure of human immunoresponse to N-glycolylneuraminic acid epitope contained in recombinant human erythropoietin. Nephron. 1996;72:599–603. doi: 10.1159/000188946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tangvoranuntakul P, et al. Human uptake and incorporation of an immunogenic nonhuman dietary sialic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12045–12050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2131556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padler-Karavani V, et al. Diversity in specificity, abundance, and composition of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in normal humans: potential implications for disease. Glycobiology. 2008;18:818–830. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borys MC, et al. Effects of culture conditions on N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) content of a recombinant fusion protein produced in CHO cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009 doi: 10.1002/bit.22644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung CH, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1109–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delbaldo C, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of cetuximab (Erbitux) alone and in combination with irinotecan in patients with advanced EGFR-positive adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1739–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saadeh CE, Lee HS. Panitumumab: a fully human monoclonal antibody with activity in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:606–613. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz SL, et al. Sensitive and specific detection of the non-human sialic Acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid in human tissues and biotherapeutic products. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muchmore EA, Milewski M, Varki A, Diaz S. Biosynthesis of N-glycolyneuraminic acid. The primary site of hydroxylation of N-acetylneuraminic acid is the cytosolic sugar nucleotide pool. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20216–20223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedlund M, et al. N-glycolylneuraminic acid deficiency in mice: implications for human biology and evolution. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4340–4346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00379-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedlund M, Padler-Karavani V, Varki NM, Varki A. Evidence for a human-specific mechanism for diet and antibody-mediated inflammation in carcinoma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18936–18941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803943105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tahara H, et al. Immunological Property of Antibodies against N-Glycolylneuraminic Acid Epitopes in Cytidine Monophospho-N-Acetylneuraminic Acid Hydroxylase-Deficient Mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:3269–3275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor RE, et al. Novel mechanism for the generation of human xeno-auto-antibodies against the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid. J Exp Med. 2010 doi: 10.1084/jem.20100575. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian J, et al. Structural characterization of N-linked oligosaccharides on monoclonal antibody cetuximab by the combination of orthogonal matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization hybrid quadrupole-quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry and sequential enzymatic digestion. Anal Biochem. 2007;364:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axworthy DB, et al. Cure of human carcinoma xenografts by a single dose of pretargeted yttrium-90 with negligible toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1802–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham T, et al. Evidence for a novel human-specific xeno-auto-antibody response against vascular endothelium. Blood. 2009;114:5225–5235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jahn EM, Schneider CK. How to systematically evaluate immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins - regulatory considerations. N Biotechnol. 2009;25:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galili U, et al. Enhancement of antigen presentation of influenza virus hemagglutinin by the natural human anti-Gal antibody. Vaccine. 1996;14:321–328. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benatuil L, et al. The influence of natural antibody specificity on antigen immunogenicity. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2638–2647. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel-Motal UM, Wigglesworth K, Galili U. Mechanism for increased immunogenicity of vaccines that form in vivo immune complexes with the natural anti-Gal antibody. Vaccine. 2009;27:3072–3082. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koren E, et al. Recommendations on risk-based strategies for detection and characterization of antibodies against biotechnology products. J Immunol Methods. 2008;333:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shankar G, Pendley C, Stein KE. A risk-based bioanalytical strategy for the assessment of antibody immune responses against biological drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:555–561. doi: 10.1038/nbt1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson JM. Medicine. A history lesson for stem cells. Science. 2009;324:727–728. doi: 10.1126/science.1174935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin MJ, Muotri A, Gage F, Varki A. Human embryonic stem cells express an immunogenic nonhuman sialic acid. Nat Med. 2005;11:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nm1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin MJ, Muotri A, Gage F, Varki A. Response to Cerdan et al.: Complement targeting of nonhuman sialic acid does not mediate cell death of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1115. doi: 10.1038/nm1006-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Hoeyveld E, Bossuyt X. Evaluation of seven commercial ELISA kits compared with the C1q solid-phase binding RIA for detection of circulating immune complexes. Clin Chem. 2000;46:283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campagnari AA, Gupta MR, Dudas KC, Murphy TF, Apicella MA. Antigenic diversity of lipooligosaccharides of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:882–887. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.882-887.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greiner LL, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strain 2019 produces a biofilm containing N-acetylneuraminic acid that may mimic sialylated O-linked glycans. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4249–4260. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4249-4260.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagneux P, et al. Proteomic comparison of human and great ape blood plasma reveals conserved glycosylation and differences in thyroid hormone metabolism. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;115:99–109. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Debeire P, Montreuil J, Moczar E, van HH, Vliegenthart JF. Primary structure of two major glycans of bovine fibrinogen. Eur J Biochem. 1985;151:607–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.