In this series, a clinician extemporaneously discusses the diagnostic approach (regular text) to sequentially presented clinical information (bold). Additional commentary on the diagnostic reasoning process (italics) is integrated throughout the discussion.

CLINICAL INFORMATION: A 53-YEAR-OLD WOMAN PRESENTED TO THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT WITH SUDDEN ONSET OF SHORTNESS OF BREATH

Clinician The differential diagnosis of acute onset of shortness of breath is relatively narrow, and includes pulmonary thromboembolism, pneumothorax, anaphylaxis, airway obstruction, metabolic acidosis, flash pulmonary edema, or arrhythmia. We need a clear understanding of when her symptoms began to sort among the diagnostic possibilities. Patients may not recognize an insidious onset of symptoms and present for medical attention only when the process becomes severe. Inquiry regarding chest pain, cough, or other associated symptoms may delineate a cardiac condition, a primary pulmonary process, or a manifestation of another systemic illness. Underlying host factors, such as immune status or other co-morbidities, may broaden the differential for dyspnea.

Diagnostic Reasoning Clinical diagnostic reasoning is a complex process. To solve clinical problems, clinicians use multiple strategies. They draw on knowledge and past experiences to formulate diagnoses. Careful data acquisition, including the history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing, allows for further refinement and discrimination among illnesses for an accurate diagnosis.1Throughout this process, experienced clinicians apply heuristics, which are mental shortcuts or simple decision-making strategies, also known as “rules of thumb.” Heuristics make use of less than complete information and are often accurate, thus enabling efficient care, but can also lead to cognitive errors.2In this case, the clinician emphasizes the importance of the tempo of the patient’s presentation. Obtaining more information about the clinical presentation will allow the clinician to narrow the differential diagnoses for acute shortness of breath. With the correct application of heuristics, the clinician will efficiently and accurately diagnose the etiology of the patient’s dyspnea.

Over the past year, the patient described progressive worsening of breathlessness with routine household chores, now upon minimal activity. On the day of presentation to the emergency room, the shortness of breath suddenly became worse, and she developed breathless at rest. Her symptoms were not associated with fever, chest pain, cough, or palpitations.

Ten years prior, she was diagnosed with alcoholic dilated cardiomyopathy. She had a history of heavy alcohol use for many years and quit drinking upon diagnosis. At that time, her echocardiogram showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 25% and an end-diastolic dimension of 66 mm (normal, 35–55 mm). Cardiac catheterization showed no evidence of coronary artery disease. She received a beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and loop diuretic; she declined placement of an implantable defibrillator. Despite adherence to her medical management and alcohol cessation, she remained in New York Heart Association Functional Class III, with marked limitation in her physical activity for the subsequent 9 years. She denied worsening lower extremity edema, leg pain, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or orthopnea.

Treatment of alcoholic cardiomyopathy is similar to that of other forms of heart failure and should include alcohol cessation. In this case, the patient’s symptoms were stable for 9 years, consistent with alcohol cessation and adherence to medical therapy. New progressive dyspnea for the past year raises concerns of progression of heart failure or a superimposed medical condition. However, her sudden breathlessness on the day of admission is inconsistent with worsening heart failure unless attributed to ischemia or arrhythmia. She should undergo a careful evaluation for other causes of her clinical deterioration.

The clinician recognizes the complexity of this patient and attempts to place her illness into a framework. The framing effect is one of many heuristics in clinical reasoning described by cognitive psychologists. Clinicians use contextual factors, experience with similar cases, and specific details of the case history to frame the patient’s problem.3,4 In this case, the patient’s problem can be framed in at least two ways, emphasizing the importance of the tempo of the patient’s presentation: acute shortness of breath in the setting of heart failure or progressive dyspnea despite adherence to medical management of heart failure. The two different framing statements trigger different diagnostic considerations. Here, the clinician recognizes that this patient’s acute dyspnea is not typical for a patient with alcoholic cardiomyopathy on appropriate therapy and therefore desires more information related to her case.

Another way of using the framing effect to solve clinical problems is to articulate one or more problem presentations, usually a one-sentence summary defining the clinical problem in the case. Clinicians use problem representations as a way to synthesize and abstract the details of a particular case so as to trigger memories of prior experiences with similar cases.1 The framing effect cannot be avoided as each diagnostic problem must be framed or represented in order to be solved. In complex case presentations, it is helpful to consider the case from several perspectives or frames to prevent errors in diagnostic reasoning.4

The patient also had a long-standing history of iron deficiency anemia due to menorrhagia. She was on iron supplementation, and her hemoglobin had remained stable at 9.4 g/dl for the past 4 years. Her cardiologist and primary care physician attributed her progressive dyspnea for the past year to her heart failure and superimposed anemia. She had no other significant past history, and had not experienced any new social changes in living situation, financial changes, or illicit use of drugs or alcohol.

Although the progressive dyspnea is initially concerning for worsening anemia or an exacerbation of her heart failure, she has a stable hemoglobin and good adherence to heart failure therapy. At this point, an alternate diagnosis must be considered to explain her sudden onset of dyspnea. Complications of heart failure or flash pulmonary edema due to an increased myocardial demand from ischemia, anemia, infection, or hyperthyroidism are possible. Pulmonary embolism should also be considered, especially with a history of cardiomyopathy. The patient’s iron deficiency anemia was attributed to menorrhagia, but her age warrants consideration of occult blood loss from a gastroenterologic or gynecologic malignancy, which could subsequently cause a hypercoagulable state and resultant thromboembolism. The progressive worsening of symptoms raises concern for an underlying pulmonary process, including an atypical pneumonia, pulmonary hypertension, or interstitial lung disease. A careful physical exam will be useful.

Her physical examination showed a temperature of 98.6 °F, blood pressure of 136/80 mmHg, heart rate of 105 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 85% on room air. She was in moderate respiratory distress, but not cyanotic. Her conjunctivae showed no evidence of pallor and sclerae were anicteric. Her jugular venous pressure was normal. Diffuse crackles were heard bilaterally. Her heart rhythm was regular, without a third or fourth heart sound. Her abdomen was soft and non-distended. She had no lower extremity edema, asymmetric leg swelling, or calf tenderness, or clubbing. Her laboratory data were unremarkable. Her hemoglobin level was unchanged, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative, cardiac enzymes normal, and her B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was 817 pg/ml (normal 0–100). The 12-lead electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia without ischemic changes. She received supplemental oxygen and intravenous furosemide for presumed pulmonary edema. After 30 min, her respiratory distress persisted, and a chest radiograph was obtained (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph with cardiomegaly, diffuse interstitial infiltrates, and bilateral pneumothoraces.

The patient’s physical exam is remarkable for hypoxia and pulmonary crackles, but does not otherwise suggest volume overload. Patients with interstitial lung disease can have a clinical presentation similar to this patient. However, other etiologies such as pulmonary embolism or a small pneumothorax cannot be excluded as they may be difficult to diagnose on physical exam. Stable anemia is confirmed, and initial cardiac enzymes and her electrocardiogram do not suggest acute cardiac ischemia. The B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is likely elevated because of increased ventricular strain. The patient’s chest radiograph shows cardiomegaly, diffuse interstitial infiltrates, and bilateral pneumothoraces, providing multiple potential explanations for her acute respiratory distress. Before any further evaluation, her pneumothoraces must be addressed. The size of the pneumothorax and severity of her symptoms determine whether tube thoracostomy is warranted.

The reason for bilateral pneumothoraces in a patient with cardiomyopathy and anemia is not apparent. Review of this patient’s medical history as well as further imaging will be necessary to determine the cause of this patient’s long-standing dyspnea and bilateral pnuemothoraces.

Intravenous furosemide was initially given to the patient for presumed pulmonary edema from congestive heart failure. However, her physical findings (lack of jugular venous distention, cardiac gallop, or edema) were inconsistent with this diagnosis. Anchoring on the diagnosis of heart failure may have led to incorrect initial management of the patient. Anchoring may be defined as the lack of adjustment of pre-test probabilities based on new information. Premature closure may be considered an extreme case of anchoring, where a diagnosis is maintained despite lack of supporting evidence.3,4

Bilateral chest tubes were placed with immediate resolution of her respiratory distress.

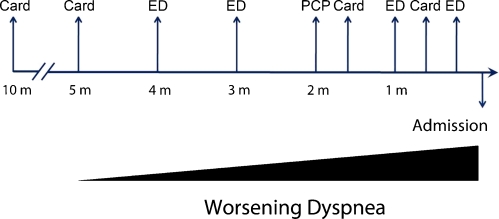

Review of her records within the same medical system demonstrates that the patient sought care eight times in the 10 months prior to this admission. She continued with complaints of worsening dyspnea (Fig. 3) despite adherence with medications. Within the preceding 4 months, the patient was evaluated four times in the emergency department, diagnosed with pulmonary edema from heart failure, and treated each time with intravenous furosemide. She saw her primary care physician and her cardiologist 2 months prior to admission, and each attributed her progressive symptoms to anemia and heart failure. Her oral diuretic dose was increased, and despite adjustment in her medication regimen, she had no improvement in her breathlessness. A review of prior chest radiographs showed progression of interstitial infiltrates, consistent with an interstitial lung disease.

Figure 3.

The patient was evaluated eight times in the 10 months prior to the current presentation and diagnosis. Card = Cardiology, ED = emergency department, PCP = primary care physician.

Multiple visits to different providers within one system led to diagnosis momentum, whereby sequential clinicians continue to accept and apply the initial diagnostic label. Diagnosis momentum commonly occurs during initial communication between physicians, underscoring the importance of ensuring that all data are carefully reviewed prior to the acceptance of any diagnosis.4,5The possibility of anemia and cardiomyopathy as a cause of worsening dyspnea was ascribed to the patient by multiple providers, which may have hindered further evaluation for dyspnea.

A high-resolution chest computed tomography showed uniformly distributed, severe interstitial lung disease with small intraparenchymal cysts and bilateral pneumothoraces.

Cystic interstitial lung disease with pneumothoraces narrows the differential diagnosis to emphysema, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), or Langerhan’s cell histiocystosis. Other possible disease processes include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or sarcoidosis. Emphysema may present with pneumothoraces and a chest CT with interstitial disease. However, the cystic air spaces are often not as uniform as can be seen lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis may also produce a cystic pattern, but often the cysts are surrounded by damaged parenchyma. Cystic air spaces and pnuemothoraces are also a prominent part of Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis.

To distinguish between LAM and pulmonary Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis, a biopsy is needed to further characterize the lung histology.

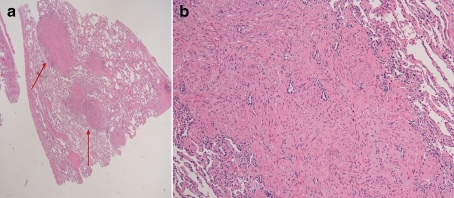

A lung wedge resection (Fig 2) showed proliferation of smooth muscle nodules. The nodules stained positively for actin, confirming a diagnosis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained pathology of right lower lung wedge resection. Panel A, low magnification, nodules of smooth muscle proliferation seen in an interstitial pattern (arrows). Panel B, higher magnification of a smooth muscle nodule confirmed the diagnosis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

DISCUSSION

In everyday practice, physicians use their medical knowledge, experience, and clinical reasoning to diagnose and treat patients. In doing so, they commonly use heuristics, or cognitive short cuts, to recognize symptom patterns (Table 1). Heuristics are necessary to allow for efficient reasoning and are usually accurate, but at times can lead to cognitive errors. In this case, cognitive errors including failure to re-frame the case along with diagnosis momentum may have contributed to the diagnostic delay for this rare condition.

Table 1.

| Heuristics |

| Anchoring—the tendency to fail to adjust the initial impression once other information is known |

| Diagnosis momentum—once a diagnostic label is attached to a patient, it is more difficult to remove |

| Framing effect—being influenced by the particular context in which the problem is framed or presented |

| Premature closure—accepting a diagnosis before it has been fully verified and stop considering other possibilities after reaching a diagnosis |

Clinicians will inevitably encounter medical errors as real-world time constraints can hinder ideal circumstances for decision making. Although all specialties are vulnerable, cognitive errors are more common in specialties with clinical uncertainties, such as internal, family, and emergency medicine.3 Understanding how such errors are made and taking corrective action to avoid them is paramount to providing safe and effective clinical care.3,4

Data on the types and causes of medical errors are limited. Graber and colleagues developed taxonomy for medical errors by internists and the relative contributions of system-related and cognitive components.5 They reviewed 100 cases of medical diagnostic errors and found the majority involved cognitive errors, either alone (28%) or in combination with a system-related error (46%). Of those attributed to cognitive errors, most (82%) involved faulty synthesis, the flawed processing of available information, and not faulty medical knowledge or data gathering. The failure to review serial chest radiographs in the context of the patient’s worsening clinical symptoms demonstrates evidence of inappropriate data gathering, but the heuristics used resulted in faulty synthesis and a delay in diagnosis.

While some intuitive strategies have been proposed to reduce diagnostic errors in medicine 3, little evidence exists to suggest these strategies work. Developing an awareness of the limitations of some heuristics used in decision making may prevent errors. Another strategy includes the use of metacognition, a reflective approach to diagnosis formulation. Metacognition involves awareness of the learning process and one’s own limitations as well as the ability to self-critique. It also involves the ability to step back from a problem and consider a broader differential or how a clinical diagnosis is reasoned.6

Prompt follow-up after treatment may allow time to reflect and permit clinicians to monitor whether there was an appropriate clinical response to the treatment. In this case, the patient had multiple medical evaluations, but there was no consistent follow-up with her primary care physician to assess specifically whether she improved with titrating diuretics. Remembering the primary symptoms with a focused visit for clinical response may have allowed the diagnosis to be made sooner .4

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2217–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wegwarth O, Gaissmaier W, Gigerenzer G. Smart strategies for doctors and doctors-in-training. Med Educ. 2009;43(8):721–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775–80. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redelmeier D. Improving patient care. The cognitive psychology of missed diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:115–120. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1493–99. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croskerry P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decision making. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:110–120. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]