Abstract

It is well recognized that the C terminus (CT) plays a crucial role in modulating G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) transport from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cell surface. However the molecular mechanisms that govern CT-dependent ER export remain elusive. To address this issue, we used α2B-adrenergic receptor (α2B-AR) as a model GPCR to search for proteins interacting with the CT. By using peptide-conjugated affinity matrix combined with proteomics and glutathione S-transferase fusion protein pull-down assays, we identified tubulin directly interacting with the α2B-AR CT. The interaction domains were mapped to the acidic CT of tubulin and the basic Arg residues in the α2B-AR CT, particularly Arg-437, Arg-441, and Arg-446. More importantly, mutation of these Arg residues to disrupt tubulin interaction markedly inhibited α2B-AR transport to the cell surface and strongly arrested the receptor in the ER. These data provide the first evidence indicating that the α2B-AR C-terminal Arg cluster mediates its association with tubulin to coordinate its ER-to-cell surface traffic and suggest a novel mechanism of GPCR export through physical contact with microtubules.

Keywords: Adrenergic Receptor, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Microtubules, Trafficking, Tubulin, Cell Surface Transport, ER Export

Introduction

The precise function of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)2 relies on highly regulated intracellular trafficking processes, including export of nascent receptors from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cell surface, agonist-evoked internalization of the receptors from the cell surface to endosomes, recycling of the internalized receptors from the endosomes back to the cell surface, and targeting to the lysosome for degradation, which dictate proper expression and correct targeting to the functional destination of the receptors. Over the past decades, substantial studies have been focused on the events of endocytosis, recycling, and degradation of GPCRs (1–5). In contrast, the molecular mechanisms underlying the export trafficking of newly synthesized GPCRs from the ER to the cell surface remain largely unknown.

It has been well documented that GPCR export to the cell surface involve direct interactions with multiple regulatory proteins such as ER chaperones, accessory proteins, and receptor activity modifying proteins, which may stabilize receptor conformation, facilitate receptor maturation, and promote receptor delivery to the plasma membrane (6–11). In addition, GPCR dimerization may regulate proper receptor folding and assembly, which will influence the receptors ability to pass through the ER quality control mechanism (12, 13). As an initial approach to study GPCR cell surface transport, we have determined the role of the Ras-like small GTPases in the ER-to-cell surface movement of nascent GPCRs. Our studies have shown that the Rab and Sar1/ARF subfamilies play an important role in regulation of GPCR transport from the ER to the cell surface along the secretory pathway. More importantly, the small GTPases Rab1, Rab6, Rab8, and Sar1 are able to selectively or differentially modulate the cell surface transport of GPCRs, suggesting that distinct GPCRs with similar structural features may use different pathways to move to the cell surface en route from the ER and the Golgi (14–21). More recently, we have demonstrated that Rab8 and ARF1 directly interact with the receptors to modulate receptor cell surface transport (18, 19).

An essential role for the C terminus (CT) in the ER-to-cell surface transport has been described for a number of GPCRs and indeed, several highly conserved motifs, which control receptor export trafficking, have been identified in the CT (22–29). However the molecular mechanisms remain poorly defined. To address this issue, we sought to identify proteins interacting with the α2B-AR CT. We report here that the α2B-AR CT directly interacts with α- and β-tubulin. More importantly, the basic Arg residues in the CT not only mediate α2B-AR interaction with tubulin but also are required for receptor export from the ER to the cell surface. These data provide the first evidence implicating that the cargo GPCRs may directly contact with microtubules to coordinate their cell surface transport.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Rat α2B-AR in vector pcDNA3 was kindly provided by Dr. Stephen M. Lanier (Medical University of South Carolina). The dominant negative arrestin-3 mutant Arr3-(201–409) and the dominant negative dynamin mutant DynK44A were provided by Dr. Jeffrey L. Benovic (Thomas Jefferson University). Antibodies against phospho-ERK1/2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-ERK1/2 antibody detecting total ERK1/2 expression was from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). The β-tubulin antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The α-tubulin antibody (DM1A), UK14304, and rauwolscine were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. 4% crosslinked agarose beads were purchased from Agarose Bead Technologies (Tampa, FL). The ER marker pDsRed2-ER was from BD Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA). The α2B-AR C-terminal peptide NH2-NQDFRRAFRRILCRPWTQTGW-COOH, C-terminal peptide mutant (in which three Arg at positions 437, 441, and 446 were mutated to Glu) NH2-NQDFERAFERILCEPWTQTGW-COOH, and third intracellular loop (ICL3) peptide NH2-GKNVGVASGQWWRRRTQLSRE-OH were synthesized, purified by HPLC to >75% and directly conjugated to agarose beads by Biosynthesis Inc. (Lewisville, TX). Purified bovine tubulin was purchased from Cytoskeleton Inc. (Denver, CO). [3H]RX821002 (specific activity = 41 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). Penicillin-streptomycin, l-glutamine, and trypsin-EDTA were from Invitrogen (Rockville, MD). All other materials were obtained as described elsewhere (30–32).

Plasmid Constructions

α2B-AR tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) at its CT (α2B-AR-GFP) was generated as described previously (14). Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein constructs coding the α2B-AR CT were generated in the pGEX-4T-1 vector as described previously (19). All mutants were made with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. The sequence of each construct was confirmed by restriction mapping and nucleotide sequence analysis.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection

HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 units/ml streptomycin. Transient transfection of the cells was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) as described previously (14, 30). For intact cell ligand binding and ERK1/2 activation, HEK293 cells were cultured in 6-well dishes and transfected with 1.0 μg of plasmid. For fluorescence microscopy, HEK293 cells were cultured in 6-well dishes transfected with 0.5 μg of plasmid. Transfection efficiency was estimated to be greater than 80% based on the GFP fluorescence.

Identification of Proteins Interacting with the α2B-AR CT by Peptide-conjugated Affinity Matrix

Rat brains were homogenized in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA, 9 mm KCl, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton at a ratio of 3 ml of buffer to 1 g of rat brain tissue. After homogenization, lysates were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C, and the supernatant was then collected. The total cytosolic extracts were pre-cleared three times with 2 ml of blank agarose beads for 2 h at 4 °C. 4 ml of pre-cleared rat brain cytosolic extract (∼20 mg) were then incubated with l ml of the α2B-AR CT-conjugated agarose beads with gentle rotation overnight at 4 °C. The resin was washed three times with 4 ml of homogenization buffer at 4 °C, and bound proteins were then eluted with 1 ml of denaturing buffer (7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 4% Chaps, 30 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 20% glycerol). The eluted proteins were separated by 2-dimensional gels and stained with Sypro Ruby. Images were then captured using a Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager. Proteins of interest were picked using the Ettan Spot Handling Work station (GE Healthcare), digested with trypsin and identified by LTQ electrospray mass spectrometry. The identity of the sequences was then revealed by matching the spectrum against a database of previously generated spectra with MASCOT as described (33).

GST Fusion Protein Pull-down Assays

The GST-fusion proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified using a glutathione-affinity matrix as described previously (18, 19). Immobilized fusion proteins were either used immediately or stored at 4 °C for no longer than 3 days. Each batch of fusion protein used in experiments was first analyzed by Coomassie Blue staining following SDS-PAGE.

Tubulin purified from bovine brain was reconstituted in general tubulin buffer (G-PEM: 80 mm PIPES, pH 6.9, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EGTA, 50 mm GTP). Tubulin lacking the acidic CT (tubulin S) was prepared by limited proteolysis of rat tubulin with subtilisin as described (34, 35). 2 μl of GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with 1 μg of purified tubulin (unless otherwise stated) or tubulin S in G-PEM plus 2% Nonidet P-40 and 100 mm NaCl. 10 μl of GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with 100 μg of rat brain cytosolic extracts in homogenization buffer plus 100 mm NaCl. To determine the effect of salt on the interaction with tubulin, the interaction was carried out in buffer containing increasing concentrations of NaCl from 0 to 400 mm. Incubations were carried out at room temperature for 1 h. The resin was then washed three times with binding buffer. The bound proteins were solubilized in 20 μl of 2× SDS-gel buffer and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The bound tubulin was detected by Western blotting with either α-tubulin or β-tubulin specific antibodies. The membranes were stained with Amido Black to confirm equal input of fusion proteins into each reaction. As the concentrations of tubulin and tubulin S in GST pull-down assays was lower than that required for polymerization, both tubulin and tubulin S are likely dimeric, but not polymerized.

Co-immunoprecipitation of α2B-AR and Tubulin

HEK293 cells cultured on 100-mm dishes were transfected with 2 μg of HA-tagged α2B-AR or its mutant 3R-3A in which Arg-437, Arg-441, and Arg-446 were mutated to Ala for 36 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS, harvested and lysed with 500 μl of lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture. After gentle rotation for 1 h, samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 × g and the supernatant was incubated with 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose for 1 h at 4 °C to remove nonspecific bound proteins. Samples were then incubated with 3 μg of anti-HA antibodies overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation followed by an incubation with 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose 4B beads for 5 h. Resin was collected by centrifugation and washed three times each with 500 μl of lysis buffer without SDS. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with 100 μl of 1× SDS gel loading buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. α2B-AR and tubulin in the immunoprecipitates were detected by Western blotting using anti-HA and anti-tubulin antibodies, respectively.

Radioligand Binding

Cell-surface expression of α2B-AR in HEK293 cells was measured by ligand binding on intact cells using [3H]RX821002 as described previously (30, 31). HEK293 cells cultured on 6-well dishes were transfected with α2B-AR or its mutants as described above. After transfection for 6 h the cells were split into 12-well dishes pre-coated with poly-l-lysine at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well. After transfection 48 h, the cells were incubated with [3H]RX821002 at a concentration of 20 nm in a total of 400 μl for 90 min at room temperature. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold DMEM, and the retained radioligand was then extracted by digesting the cells in 300 μl of 1 m NaOH for 2 h. The amount of radioactivity retained was measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

For measurement of α2B-AR internalization, HEK293 cells were cultured 6-well dishes and transfected with 0.5 μg of α2B-AR and 1 μg of arrestin-3 plus 1 μg of empty pcDNA3.1(-) vector, Arr3-(201–409), DynK44A, or Rab5S34N for 24 h. After starvation for 3 h, the cells were stimulated with epinephrine at a concentration of 100 μm for 1 h. The cells were washed three times with cold PBS and α2B-AR expression at the cell surface was measured by intact cell ligand binding as described above. To determine the effect of drug treatment on the cell surface expression of α2B-AR, HEK293 cell transfected with α2B-AR were incubated with GM132 (20 μm), NH4Cl (20 mm), or chloroquine (100 μm) for 6 h at 37C°.

Flow Cytometry

For measurement of α2B-AR expression at the cell surface, HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-tagged receptor for 36–48 h. The cells were collected, suspended in PBS containing 1% FBS at a density of 4 × 106 cells/ml and incubated with high affinity anti-HA-fluorescein (3F10) at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing twice with 0.5 ml of PBS/1% FBS, the cells were resuspended, and the fluorescence was analyzed on a flow cytometer (Dickinson FACSCalibur) as described (30).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

For fluorescence microscopic analysis of α2B-AR subcellular distribution, HEK293 cells were grown on coverslips pre-coated with poly-l-lysine in 6-well plates and transfected with 500 ng of α2B-AR-GFP for 36 to 48 h. For co-localization of α2B-AR with Sec24, HEK293 cells were transfected with 100 ng of α2B-AR-GFP and 400 ng of Sar1H79G. For co-localization of α2B-AR with the ER marker DsRed2-ER, HEK293 cells were transfected with 100 ng of α2B-AR-GFP and 100 ng of pDsRed2-ER. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde-4% sucrose mixture in PBS for 15 min. The coverslips were mounted, and fluorescence was detected with a Leica DMRA2 epifluorescent microscope. Images were deconvolved using SlideBook software and the nearest neighbor deconvolution algorithm (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO) as described previously (30).

Measurement of ERK1/2 Activation

HEK293 cells were cultured in 6-well dishes and transfected with 0.5 μg of α2B-AR or its mutant. At 6–8 h after transfection, the cells were split into 6-well dishes and cultured for additional 36 h. The cells were starved for at least 3 h and then stimulated with 1 μm UK14304 for 5 min. Stimulation was terminated by addition of 1× SDS gel loading buffer. After solubilizing the cells, 20 μl of total cell lysates were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. ERK1/2 activation was determined by measuring the levels of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 with phosphospecific ERK1/2 antibodies by immunoblotting (14).

Statistical Analysis

Differences were evaluated using Student's t test, and p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

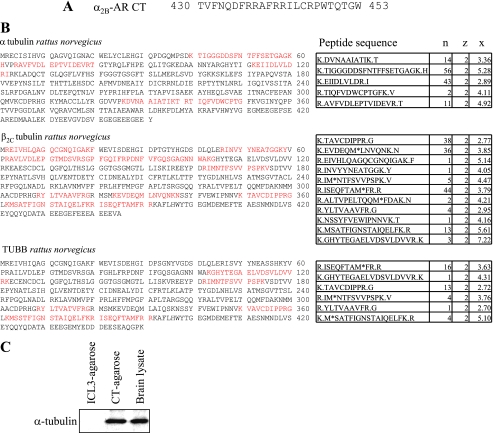

The α2B-AR CT Directly Interacts with Tubulin

To search for proteins interacting with the α2B-AR CT (Fig. 1A), the CT peptide was synthesized, directly conjugated to agarose beads and incubated with the brain cytosolic extracts. The bound proteins were eluted, separated by two-dimensional gels, and identified by LTQ electrospray mass spectrometry. The most predominant proteins pulled out from the rat brain lysates were tubulin isoforms (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis using monoclonal α-tubulin-specific antibodies further revealed that tubulin was pulled out by the CT-conjugated agarose matrix. In contrast, a control peptide derived from the ICL3 of α2B-AR did not pull down detectable tubulin from brain lysates (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Identification of tubulin isoforms as interacting proteins of the α2B-AR CT. A, sequence of the α2B-AR CT that was directly fused to agarose beads to generate affinity matrix. B, identification of tubulin interacting with the α2B-AR CT-conjugated agarose. CT-conjugated agarose beads were incubated with rat brain lysates and bound proteins were eluted and separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Spots of interest were picked, digested, and identified by LTQ electrospray mass spectroscopy as described under “Experimental Procedures.” n, number of times the sequence showed up in the spot of interest; z, charge of the peptide sequence; x, correlation score (representation of how well the mass spectrum matches a pre-generated standard for that particular sequence). Peptides are generally considered significant with a correlation score of over 2.5 at a charge of 2, or with a correlation score of over 3 at a charge of 3. Red indicates the positions of the peptides identified by mass spectroscopy in the full length of tubulin isoforms. C, detection of α-tubulin in the eluate from CT- and ICL3-agarose beads. A small portion of the eluate was analyzed by Western blotting using α-tubulin antibodies. Similar results were obtained in at least three separate experiments.

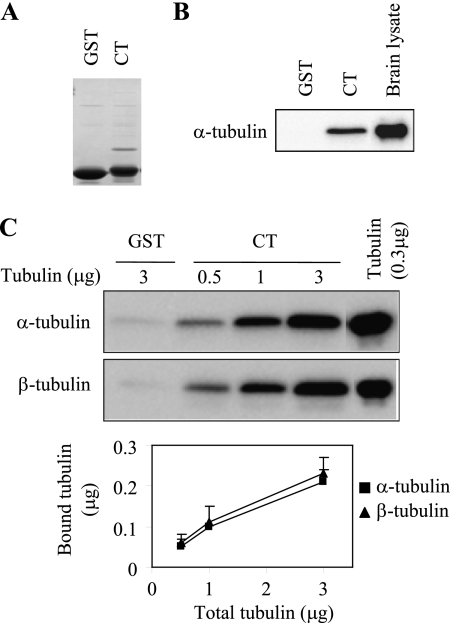

We next used GST pull-down assays to confirm the interaction between the α2B-AR CT and tubulin. The GST fusion protein encoding the α2B-AR CT, but not GST, strongly interacted with tubulin from total brain extracts (Fig. 2, A and B). To determine if the α2B-AR CT could directly interact with tubulin, the GST fusion proteins were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified bovine brain tubulin. The GST-α2B-AR CT was able to bind to purified α- and β-tubulin (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that the α2B-AR CT directly interacts with tubulin.

FIGURE 2.

The α2B-AR CT directly interacts with α- and β-tubulin. A, Coomassie Blue staining of GST and GST-α2B-AR CT fusion proteins. B, interaction of the α2B-AR CT with tubulin from rat brain lysates. GST and GST-CT fusion proteins were incubated with rat brain lysates (100 μg) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Bound α-tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting. C, interaction of the α2B-AR CT with purified tubulin. GST-CT fusion proteins were incubated with increasing amount of purified tubulin (0.5 to 3 μg). Incubation of GST with 3 μg of tubulin was used as a control. Both α- and β-tubulin were analyzed by Western blotting. Bottom panel: quantitative data expressed as the mean ± S.E. of five experiments.

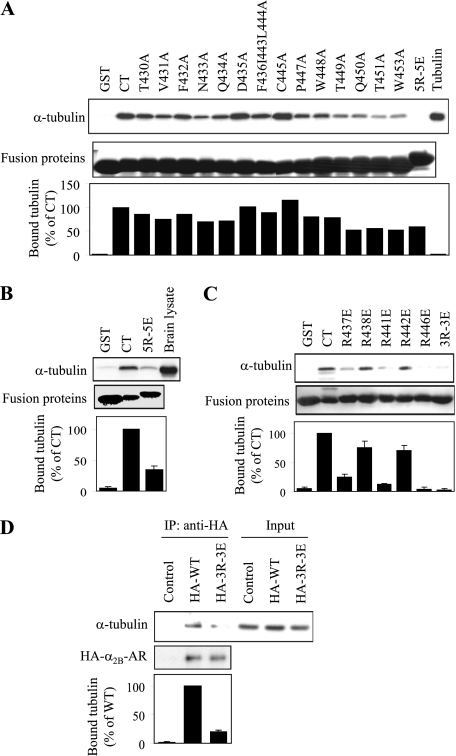

Arg Residues Mediate the α2B-AR CT Interaction with Tubulin

Next, we identified specific residues in the α2B-AR CT responsible for interacting with tubulin. In the first series of experiments, each non-basic residue in the CT was mutated to Ala, whereas 5 Arg residues were mutated to Glu together (5R-5E), which will presumably preserve the amphipathic character of the α-helix 8, but reverse the charge on the face of the helix. The abilities of mutated CT to interact with purified tubulin and brain extracts were determined in the GST fusion protein pull-down assay. Mutation of the non-basic residues had variable effects on the affinity of the α2B-AR CT for tubulin, but was insufficient to abolish the interaction. Simultaneous mutation of the 5 Arg residues to Glu, on the other hand, abolished the interaction of the α2B-AR CT with purified tubulin (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, mutation of the 5 Arg residues also markedly inhibited the α2B-AR CT interaction with tubulin from the brain extracts (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that Arg residues are the main determinant of the interaction between the α2B-AR CT and tubulin.

FIGURE 3.

Identification of essential residues in the α2B-AR CT required for tubulin interaction. A, effect of mutating residues in the CT of α2B-AR individually or in combination on the interaction with purified tubulin. The Phe-361, Ile-443, and Leu-444 residues were mutated to Ala together and 5 Arg residues at positions of 437, 438, 441, 442, and 446 mutated to Glu (5R-5E) together, and all other residues mutated to Ala individually. The effect of mutation on the α2B-AR CT interaction with purified tubulin was determined by GST fusion protein assays. Each fusion protein was incubated with 1 μg of purified tubulin and bound tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting with α-tubulin antibodies as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Bottom panel: quantitative data expressed as percentages of tubulin interacting with wild-type C terminus and presented as the mean value of two separate experiments with similar results. B, effect of mutating the 5 Arg residues to Glu on the ability of α2B-AR CT to interact with tubulin from the rat brain cytosolic extract. GST and GST fusion proteins encoding the α2B-AR CT or its mutant 5R-5E were incubated with 100 μg of rat brain cytosolic extracts. C, effect of mutating individual Arg residue or 3 Arg residues at positions of 437, 441, and 446 together (3R-3E) to Glu on the α2B-AR CT interaction with purified tubulin as determined in A. Similar results were obtained in 3–5 different experiments. Bottom panels in B and C: quantitative data expressed as percentages of tubulin interacting with wild-type C terminus and presented as the mean ± S.E. of three experiments. D, co-immunoprecipitation of α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E with tubulin. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with empty pcDNA3.1 vector (control), HA-α2B-AR, or 3R-3E. The cells were solubilized, and the receptors were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies as described under the “Experimental Procedures.” The immunoprecipitate was separated by SDS-PAGE and the level of tubulin in the HA-immunoprecipitate was determined by Western blotting using α-tubulin antibodies (upper panel) and the immunoprecipitated receptor revealed using with anti-HA antibodies (middle panel). Bottom panel: quantitative data expressed as percentages of tubulin interacting with wild-type α2B-AR and presented as the mean ± S.E. of three experiments.

In the second series of experiments, each Arg residue in the α2B-AR CT was individually mutated to Glu and the effect on the CT interaction with tubulin was measured. Surprisingly, individual mutation of Arg-437, Arg-441, and Arg-446 or simultaneous mutation of all three Arg residues together almost completely blocked the CT interaction with tubulin, whereas mutation of Arg-438 and Arg-442 only partially inhibited the interaction (Fig. 3C). These data demonstrate that the five Arg residues in the CT unequally contribute to α2B-AR interaction with tubulin, and Arg residues at positions of 437, 441, and 446 play a crucial role in mediating α2B-AR interaction with tubulin.

In the third series of experiments, we determined if these Arg residues mediate α2B-AR interaction with tubulin in cells. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the empty vector (control), HA-tagged α2B-AR or its mutant in which Arg-437, Arg-441, and Arg-446 were mutated to Glu (3R-3E) and their interaction with tubulin was determined by co-immunoprecipitation using anti-HA antibodies. The amount of tubulin was much more in the immunoprecipitates from cells expressing wild-type α2B-AR than from cells expressing α2B-AR mutant 3R-3E and control cells (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that α2B-AR may physically associate with tubulin via C-terminal Arg residues in a cellular context.

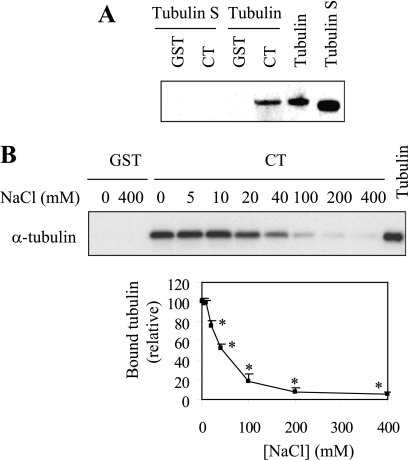

Acidic CT Mediates Tubulin Interaction with α2B-AR

Our preceding data have identified Arg residues as tubulin binding sites in the α2B-AR CT. To define the α2B-AR binding domain in tubulin, we focused on the CT of tubulin as it is negatively charged containing multiple acidic residues. To determine if the CT of tubulin interacts with α2B-AR, we generated tubulin S in which the CT of tubulin was removed and determined its ability to interact with the α2B-AR CT. GST fusion protein pull-down assay shown that tubulin S did not interact with the α2B-AR CT (Fig. 4A). These data indicate that the CT of tubulin is the α2B-AR binding site.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of the CT of tubulin and ion strength on the interaction between the α2B-AR CT and tubulin. A, effect of removing the CT of tubulin on its interaction with the α2B-AR CT. GST and GST-α2B-AR CT were incubated with 1 μg of purified tubulin or tubulin S. B, effect of increasing concentration of NaCl on the interaction between the α2B-AR CT and tubulin. GST and GST-CT were incubated with 1 μg of purified tubulin with increasing concentrations of NaCl (0–400 mm) in the reaction buffer. Upper panel, bound tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting using α-tubulin antibodies; lower panel, graphical representation of the inhibition of GST-α2B-AR CT interaction with tubulin caused by increasing concentrations of NaCl. The data shown are percentages of the bound tubulin in the absence of NaCl in the reaction buffer and presented as the mean ± S.E. of three experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus bound tubulin in the absence of NaCl.

We then determined the effect of increasing concentrations of NaCl on α2B-AR CT interaction with tubulin. The maximal levels of tubulin were pulled down in the incubation buffer containing 0, 5, and 10 mm NaCl. When NaCl concentration was increased beyond 10 mm, the amount of tubulin pulled down dropped sharply until there was almost no tubulin detectable at 400 mm NaCl (Fig. 4B). These data further demonstrate that the interaction between α2B-AR and tubulin is ionic in nature.

The Arg Residues Interacting with Tubulin Are Required for Cell Surface Expression of α2B-AR

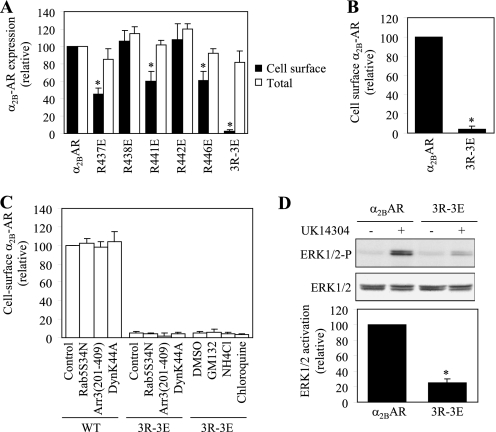

To determine the role of the interaction between α2B-AR and tubulin, we compared the cell surface expression of α2B-AR with its mutants in which the five Arg residues were mutated to Glu individually or in combination. Mutation of Arg-437, Arg-441, and Arg-446 significantly attenuated the numbers of α2B-AR at the cell surface, whereas mutations of Arg-438 and Arg-442 did not have a clear inhibitory effect. Furthermore, simultaneous mutation of all five Arg residues (5R-5E) (not shown) or three Arg residues at positions 437, 441, and 446 (3R-3E) abolished α2B-AR transport to the cell surface (Fig. 5A). In contrast the cell surface expression, the total α2B-AR expression was very much the same between wild type and mutants (Fig. 5A). These data demonstrate that the positively charged Arg cluster in the CT not only mediates α2B-AR interaction with tubulin but also is required for α2B-AR transport to the cell surface.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of mutating tubulin binding sites on the cell surface expression of α2B-AR. A, cell surface and total expression of wild-type α2B-AR and its mutants in which five Arg residues were mutated individually or in combination. HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged α2B-AR or its mutants. The expression of the receptors at the cell surface was determined by intact cell ligand binding using [3H]RX821002 and the total receptor expression was determined by flow cytometry detecting the GFP signal as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data shown are percentages of the mean value obtained from cells transfected with α2B-AR and are presented as the mean ± S.E. of three experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus α2B-AR. B, cell surface expression of α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E. HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-tagged α2B-AR or its mutant 3R-3E and their expression at the cell surface was determined by flow cytometry following staining by anti-HA antibodies as described in “Experimental Procedures.” The data shown are percentages of the mean value obtained from cells transfected with α2B-AR and are presented as the mean ± S.E. of four experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus α2B-AR. C, effect of blocking endocytotic transport and degradation on the cell surface expression of α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with α2B-AR or the mutant 3R-3E together with pcDNA3 vector (control) or the dominant negative mutants Arr3(201–409), DynK44A, or Rab5S34N. For drug treatment, HEK293 cells transfected with the mutant 3R-3E were treated with DMSO (control), GM132 (20 μm), NH4Cl (20 mm), or chloroquine (100 μm) for 6 h at 37C°. The data shown are presented as the mean ± S.E. of three separate experiments. D, activation of ERK1/2 by α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E. HEK293 cells were transfected with α2B-AR or the mutant 3R-3E and stimulated with UK14304 at a concentration of 1 μm for 5 min at 37 °C. ERK1/2 activation was determined by Western blot analysis using phospho-specific ERK1/2 antibodies. Upper panel: a representative blot showing ERK1/2 activation; middle panel: total ERK1/2 expression; lower panel: quantitative data expressed as percentages of ERK1/2 activation obtained from cells transfected with α2B-AR and presented as the mean ± S.E. of three experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus α2B-AR.

As the cell surface expression of α2B-AR was measured by intact cell ligand binding, to exclude the possibility that mutation of the C-terminal Arg residues alters the ability of α2B-AR to bind to its ligand, α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E were tagged with HA at their N termini and their expression at the cell surface was then measured by flow cytometry following staining with anti-HA antibodies in non-permeabilized cells. Consistent with the data obtained in ligand binding, cell surface expression of the mutant 3R-3E was reduced by 96% as compared with wild-type receptor (Fig. 5B).

To eliminate the possibility that attenuated cell surface expression of the α2B-AR mutant 3R-3E is caused by its constitutive internalization induced by the mutation, we determined the effect of transient expression of the dominant negative mutants Arr3-(201–409), DynK44A, and Rab5S34N on the cell-surface expression of the mutant. Arrestin-3, dynamin, and Rab5 have been well demonstrated to modulate endocytic trafficking of GPCRs including α2B-AR (4, 36, 37). Stimulation with 100 μm epinephrine for 1 h reduced the cell surface expression of α2B-AR by 42 ± 2% (n = 5). Co-expression of Arr3-(201–409), DynK44A, and Rab5S34N significantly attenuated epinephrine-induced α2B-AR internalization by 76 ± 5, 63 ± 8, and 54 ± 7%, respectively. In contrast, expression of Arr3-(201–409), DynK44A, and Rab5S34N did not influence the cell surface expression of α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E in the absence of agonists (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, treatment with GM132 (a proteasome inhibitor), NH4Cl, and chloroquine (two lysosome inhibitors) also did not clearly enhance the cell surface expression of the α2B-AR mutant 3R-3E (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that the reduction in the cell surface expression of the mutant 3R-3E is likely caused by defective export of newly synthesized receptor, but not increased internalization and degradation.

To further confirm the inhibitory effect of mutating the Arg residues on the cell surface expression of α2B-AR, we compared the abilities of α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E to activate downstream signaling molecules by measuring ERK1/2 activation in response to stimulation with UK14304. ERK1/2 in cells transfected with α2B-AR were markedly activated by UK14304 and this activation was almost abolished in cells expressing the mutant 3R-3E (Fig. 5D). These data further indicate an important role of three Arg residues at positions 437, 441, and 446 in α2B-AR transport to the plasma membrane.

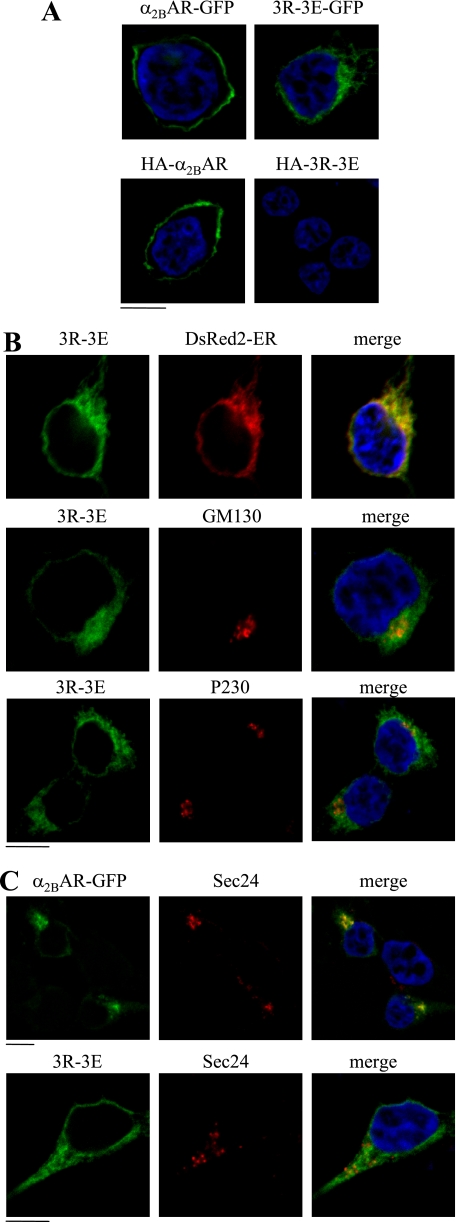

The Arg Residues Cluster Interacting with Tubulin Modulates α2B-AR Exit from the ER

We then sought to define the intracellular compartment where the Arg cluster modulates α2B-AR transport. α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E were tagged with GFP at their C termini or HA at their N termini. The cell surface expression and subcellular distribution at steady state of GFP-tagged receptors was revealed by direct fluorescent microscopy, whereas HA-tagged receptors expressed at the cell surface were detected following staining by anti-HA antibodies in non-permeabilized cells. Wild-type α2B-AR tagged either with GFP or HA was robustly expressed at the cell surface (Fig. 6A), whereas GFP-tagged 3R-3E mutant displayed an entirely intracellular distribution pattern and HA-tagged 3R-3E was not detectable (Fig. 6A). These data are consistent with the remarkable reduction in the cell surface expression of the mutated receptor.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of mutating tubulin binding Arg residues on the subcellular distribution of α2B-AR. A, HEK293 cells cultured on coverslips were transfected with GFP- or HA-tagged α2B-AR or its mutant 3R-3E. The subcellular distribution of the receptors was revealed by detecting GFP fluorescence (upper panel) and detecting HA signal following staining with anti-HA antibodies (lower panel) in non-permeabilized cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, colocalization of the α2B-AR mutant 3R-3E with the ER marker DsRed2-ER, the cis-Golgi marker GM130, and the TGN marker p230. HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged 3R-3E mutant together with pDsRed2-ER and their co-localization were revealed by fluorescence microscopy, whereas co-localization of the mutant 3R-3E with GM130 and p230 was detected after staining with specific antibody against each marker (1:50 dilution). C, colocalization of α2B-AR and its mutant 3R-3E with the ER exit sites marker Sec24. HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged α2B-AR plus Sar1H79G (upper panel) or the 3R-3E mutant alone (lower panel). α2B-AR co-localization with Sec24 was revealed after staining with anti-Sec24 antibodies (1:50 dilution). Green, GFP-tagged α2B-AR; red, markers; yellow, co-localization of α2B-AR with the markers; blue, DNA staining by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (nuclei). The data shown in A, B, and C are representative images of at least three independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 μm.

The α2B-AR mutant 3R-3E was then co-localized with different intracellular markers. The mutant 3R-3E was extensively co-localized with the ER marker DsER-Red, but not the Golgi marker GM130, the TGN marker p230 (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that the Arg cluster in the CT modulates α2B-AR export at the level of the ER.

We then determined if mutation of the Arg cluster could influence the transport of α2B-AR to ER exit sites. Wild-type α2B-AR was strongly co-localized with the ER exit marker Sec24 (Fig. 6C) in the presence of Sar1H79G, which has been well demonstrated to block the formation of COPII transport vesicles without influencing the recruitment of cargo to ER exit sites (32). In contrast, the mutant 3R-3E was not co-localized with Sec24 (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that mutation of the tubulin-binding site blocks α2B-AR recruitment onto ER exit sites.

DISCUSSION

The molecular mechanisms underlying the export trafficking of newly synthesized GPCRs from the ER to the cell surface have just begun to be revealed. In this article, we used α2B-AR as a model GPCR to search for proteins interacting with its CT. We found that α2B-AR, through its C-terminal Arg residues cluster, interacts with tubulin. Mutation of the Arg residues to disrupt α2B-AR interaction with tubulin markedly blocked receptor export from the ER to the cell surface. These data provide the first evidence implicating that the nascent cargo GPCRs may be able to physically contact with microtubules to promote their export trafficking, a novel mechanism responsible for GPCR export along the microtubule network.

Microtubules are an integral and highly dynamic component of the cytoskeletal network characterized by hollow tubes of α/β-tubulin dimers and modulate many intracellular trafficking processes, including ER export and ER-to-Golgi transport of newly synthesized cargo along the secretory pathway (38–42). The ER export is mediated through COPII-coated transport vesicles, which are formed on the ER membrane and move toward the Golgi along microtubule tracks. Interestingly, a recent study has demonstrated that the microtubule motor protein dynactin is able to directly interact with the COPII component Sec23 (38). A number of studies have shown that the microtubule network modulates endocytic transport and signal propagation of GPCRs (43–47). Microtubules may be also involved in the polarized targeting of GPCRs (48, 49). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the function of the microtubule network in the cell surface transport of newly synthesized GPCRs remain largely unknown. We demonstrate here that α2B-AR may directly interact with tubulin. These data provide the first evidence indicating a direct link between nascent α2B-AR and the microtubule network. However, we are not able to determine the specificity of α2B-AR interaction with α-tubulin over β-tubulin, because tubulin exists as a heterodimer of α/β-tubulin in soluble form.

The interaction between α2B-AR and tubulin appears to be ionic in nature as reversing the charge by mutation of Arg to Glu in the α2B-AR CT and deletion of acidic C terminus of tubulin effectively abolished the interaction. Furthermore, increasing ionic strength impairs the interaction between α2B-AR and tubulin. Ionic interaction of tubulin with α2B-AR is similar to its interactions with microtubule plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs), including the microtubule associated protein XMAP215, the cytoplasmic linker protein CLIP-170, and the end binding protein-1 (EB-1) (50, 51). The targeting and stabilization of microtubules at a specific contact point and the recruitment of microtubule motor proteins relies on an integrated network of +TIPs, which can interact with one another or directly interact with tubulin to form dynamic complexes at the polymerizing (+) end of a microtubule. The tubulin binding domains of XMAP215, CLIP-170, and EB-1 are structurally distinct, but all display a conserved tubulin binding face with similar properties (50, 51). Within each family are highly conserved basic residues creating a positively charged surface on the protein, which target the negatively charged EEXEEY/F motif in the CT of tubulin (50, 51). Based on homology modeling using newly published high resolution crystal structure of human β2-AR as a model (52, 53), the α2B-AR CT forms an amphipathic α-helix (also known as helix 8), parallel to the membrane, which is terminated with a Cys residue (31). The side chains of the five Arg residues, which were identified as the main determinant of tubulin interaction, project from the same face of the α-helix and are exposed to the cytosol. The side chains of Arg-437, Arg-441, and Arg-446, mutations of which caused dramatic reduction in α2B-AR interaction with tubulin, likely project from the same side on the cytosolic face.

Consistent with the involvement of the basic residues for proper cell surface expression of α2B-AR, basic motifs in the CT of GPCRs, such as angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) (28), melanin-concentrating hormone receptor (22), and chemokine receptor 5 (29) are required for proper receptor cell surface expression. For example, the membrane proximal C-terminal domain of chemokine receptor 5 CT harbors a KXXXKRXXXK motif, which mutation reduced the cell surface expression by over 75% (29). Furthermore, metabotropic glutamate receptors have been demonstrated to interact with tubulin (54, 55). In addition to induce defective export trafficking from the ER to the cell surface, mutation of the C-terminal tubulin binding site also attenuated α2B-AR signaling, specifically ERK1/2 activation. It is likely that attenuation of α2B-AR-mediated signaling is caused by the inability of the transfected cells to transport the mutated receptors to the cell surface. However, we cannot exclude that mutation may alter α2B-AR coupling to other signaling molecules involved in receptor signaling systems, which may also contribute to the disruption of normal signaling of the receptors. More importantly, basic residues are well conserved in the membrane-proximal C-terminal regions of many family A GPCRs, including several adrenergic receptors. For examples, α2A-AR, α2C-AR, αlB-AR, and β1-AR have the sequences RRXXKKXXXR, RRXXKHXXXR, KXXKRXXXR, and RKXXXR, respectively, in the C termini. Therefore, the C-terminal basic residue cluster-mediated GPCR interaction with tubulin may provide a common mechanism for export trafficking of these receptors along the microtubule network.

Although the detailed mechanism of how α2B-AR interaction with tubulin modulates its export from the ER needs further investigation, the results presented here reveal several important roles for direct interaction between α2B-AR and tubulin in the export of ER of newly synthesized receptors. First, the α2B-AR mutant lacking the tubulin binding site extensively co-localized with the ER marker, but not, the Golgi and the TGN marker, indicating that disruption of α2B-AR interaction with tubulin induced receptor accumulation in the ER. Therefore, α2B-AR interaction with tubulin plays an important role in receptor movement along the microtubule network, which is consistent with the function of the microtubule network in protein transport. Second, direct α2B-AR interaction with tubulin may position or anchor the newly synthesized cargo receptors to the microtubule network, facilitating its transport process. Third, we demonstrated that the α2B-AR mutant lacking the tubulin binding domain did not co-localize with Sec24, an ER exit sites marker, indicating that the mutated receptors are not able to be recruited onto the COPII transport vesicles. There are at least two possibilities regarding the defective targeting of the mutated α2B-AR onto the COPII vesicles. α2B-AR interaction with tubulin or microtubule network may directly affect the recruitment of nascent α2B-AR onto ER exit sites on the ER membrane through unknown mechanisms. Alternatively, mutated receptors are normally transiently transported to the COPII vesicles but with low affinity. The disruption of α2B-AR interaction with tubulin will block receptor export out of the ER and transport to other intracellular compartments which will subsequently inhibit the transport of receptors onto the COPII vesicles by mass effect. Finally, the function of the C-terminal tubulin-binding motif in modulating α2B-AR export from the ER is likely mediated through different mechanisms compared with several well-characterized ER export motifs, such as the di-acidic (DXE) and di-hydrophobic (FF) motifs, identified in non-GPCR membrane proteins. The function of these ER export motifs may mediate cargo interaction with components of the COPII vesicles, particularly Sec23 and Sec24, to facilitate cargo recruitment onto the COPII vesicles. Interestingly, these motifs are able to confer its transport ability to other ER-retained proteins. We found that the α2B-AR C-terminal tubulin-binding motifs did not enhance to γ-aminobutyric acid receptor B (GABAB) export from the ER to the cell surface (data not shown), suggesting that it cannot override the effect of ER retention motifs exist in GABAB. Nevertheless, our data suggest that the function of α2B-AR interaction with tubulin in modulating its export may be mediated through multiple regulatory mechanisms.

Among the most recent progress achieved in the GPCR export trafficking is the identification of specific sequences or motifs that are required for GPCR exit from intracellular compartments, such as the ER and the Golgi, and subsequent transport to the plasma membrane (56). These motifs are largely found in the intracellular domains, particularly the CT (23–27). For example, we have recently shown that the F(x)6LL motif in the CT modulates ER export of several family A GPCRs, including AT1R, β2-AR, α1B-AR, and α2B-AR (26, 31). The Phe residue in the F(x)6LL is likely involved in the regulation of proper folding of the receptors which is mediated through intracellular molecular interaction with other hydrophobic residues, such as Ile58 and Val42 in β2-AR and α2B-AR, respectively (31), whereas the LL motif mediates β2-AR interaction with Rab8 to modulate its transport from the Golgi (19). However, the molecular mechanism underlying the function of the LL motif in dictating α2B-AR move from the ER to the cell surface remains elusive. We have also demonstrated that the YS motif in the N terminus dictates α2-AR exit from the Golgi (21). In this report, our studies have shown that the basic Arg cluster in the CT is likely involved in the regulation of movement of nascent α2B-AR along the microtubules. These data indicate that multiple motifs coordinate α2B-AR export from the ER to the cell surface and different motifs modulate α2B-AR export at distinct steps, including correct folding, interacting with transport machinery, and transport along the microtubule network. These studies also suggest that, similar to the endocytic pathway, export trafficking of newly synthesized GPCRs is a highly coordinated process, in which the CT of the receptors plays a crucial role.

GPCR export trafficking between the ER, the Golgi and the plasma membrane is directly linked to the pathogenesis of a number of human diseases, including nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (vasopressin V2 receptor), retinitis pigmentosa (rhodopsin) and male pseudohermaphroditism (luteinizing hormone receptor) (57–59). These diseases are caused by naturally occurring mutations and truncations in the receptors which prevent proper folding and lead to ER retention of the receptors. We demonstrate here that normal cell surface transport of GPCRs is crucially modulated by the microtubule network, which dysfunction has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of many human diseases (60–62). To further explore the regulatory mechanism of the anterograde transport of nascent GPCRs may provide an important foundation for developing new therapeutic means in treating human diseases involving abnormal trafficking and signaling of GPCRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Stephen M. Lanier and Jeffrey L. Benovic for sharing reagents.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM076167 (to G. W.) and P20RR018766 Principal Investigator: Daniel R. Kapusta, and by Intramural Research Funds of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to D. L. S.).

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- AR

- adrenergic receptor

- AT1R

- angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- CT

- C terminus

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pierce K. L., Premont R. T., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. von Zastrow M. (2003) Life Sci. 74, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan C. M., Brady A. E., Nickols H. H., Wang Q., Limbird L. E. (2004) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44, 559–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu G., Krupnick J. G., Benovic J. L., Lanier S. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17836–17842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu G., Bogatkevich G. S., Mukhin Y. V., Benovic J. L., Hildebrandt J. D., Lanier S. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9026–9034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dwyer N. D., Troemel E. R., Sengupta P., Bargmann C. I. (1998) Cell 93, 455–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colley N. J., Baker E. K., Stamnes M. A., Zuker C. S. (1991) Cell 67, 255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferreira P. A., Nakayama T. A., Pak W. L., Travis G. H. (1996) Nature 383, 637–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McLatchie L. M., Fraser N. J., Main M. J., Wise A., Brown J., Thompson N., Solari R., Lee M. G., Foord S. M. (1998) Nature 393, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Achour L., Scott M. G., Shirvani H., Thuret A., Bismuth G., Labbé-Jullié C., Marullo S. (2009) Blood 113, 1938–1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Y., Chen C., Kotsikorou E., Lynch D. L., Reggio P. H., Liu-Chen L. Y. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1673–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salahpour A., Angers S., Mercier J. F., Lagacé M., Marullo S., Bouvier M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33390–33397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou F., Filipeanu C. M., Duvernay M. T., Wu G. (2006) Cell Signal. 18, 318–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu G., Zhao G., He Y. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47062–47069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X., Wang G., Dupré D. J., Feng Y., Robitaille M., Lazartigues E., Feng Y. H., Hébert T. E., Wu G. (2009) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330, 109–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Filipeanu C. M., Zhou F., Fugetta E. K., Wu G. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 69, 1571–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Filipeanu C. M., Zhou F., Claycomb W. C., Wu G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41077–41084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dong C., Zhang X., Zhou F., Dou H., Duvernay M. T., Zhang P., Wu G. (2010) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333, 174–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dong C., Yang L., Zhang X., Gu H., Lam M. L., Claycomb W. C., Xia H., Wu G. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20369–20380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dong C., Wu G. (2007) Cell Signal. 19, 2388–2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong C., Wu G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38543–38554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tetsuka M., Saito Y., Imai K., Doi H., Maruyama K. (2004) Endocrinology 145, 3712–3723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robert J., Clauser E., Petit P. X., Ventura M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2300–2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schülein R., Hermosilla R., Oksche A., Dehe M., Wiesner B., Krause G., Rosenthal W. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol. 54, 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bermak J. C., Li M., Bullock C., Zhou Q. Y. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 492–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duvernay M. T., Zhou F., Wu G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30741–30750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tai A. W., Chuang J. Z., Bode C., Wolfrum U., Sung C. H. (1999) Cell 97, 877–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gáborik Z., Mihalik B., Jayadev S., Jagadeesh G., Catt K. J., Hunyady L. (1998) FEBS Lett. 428, 147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Venkatesan S., Petrovic A., Locati M., Kim Y. O., Weissman D., Murphy P. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40133–40145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duvernay M. T., Dong C., Zhang X., Robitaille M., Hébert T. E., Wu G. (2009) Traffic 10, 552–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duvernay M. T., Dong C., Zhang X., Zhou F., Nichols C. D., Wu G. (2009) Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 751–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dong C., Zhou F., Fugetta E. K., Filipeanu C. M., Wu G. (2008) Cell Signal. 20, 1035–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simon V., Guidry J., Gettys T. W., Tobin A. B., Lanier S. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40310–40320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rostovtseva T. K., Sheldon K. L., Hassanzadeh E., Monge C., Saks V., Bezrukov S. M., Sackett D. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18746–18751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Knipling L., Hwang J., Wolff J. (1999) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 43, 63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeGraff J. L., Gagnon A. W., Benovic J. L., Orsini M. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11253–11259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DeGraff J. L., Gurevich V. V., Benovic J. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43247–43252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Driskell O. J., Mironov A., Allan V. J., Woodman P. G. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mizuno M., Singer S. J. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107, 1321–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Presley J. F., Cole N. B., Schroer T. A., Hirschberg K., Zaal K. J., Lippincott-Schwartz J. (1997) Nature 389, 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ralston E., Ploug T., Kalhovde J., Lomo T. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 875–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saraste J., Svensson K. (1991) J. Cell Sci. 100, 415–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Popova J. S., Johnson G. L., Rasenick M. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21748–21754 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Head B. P., Patel H. H., Roth D. M., Murray F., Swaney J. S., Niesman I. R., Farquhar M. G., Insel P. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26391–26399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen C., Li J. G., Chen Y., Huang P., Wang Y., Liu-Chen L. Y. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7983–7993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Popova J. S., Rasenick M. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30410–30418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sarma T., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T., Hope T. J., Rasenick M. M. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 848–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saunders C., Limbird L. E. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 19035–19045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saunders C., Limbird L. E. (2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 44–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Slep K. C., Vale R. D. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 976–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mishima M., Maesaki R., Kasa M., Watanabe T., Fukata M., Kaibuchi K., Hakoshima T. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10346–10351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rosenbaum D. M., Cherezov V., Hanson M. A., Rasmussen S. G., Thian F. S., Kobilka T. S., Choi H. J., Yao X. J., Weis W. I., Stevens R. C., Kobilka B. K. (2007) Science 318, 1266–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cherezov V., Rosenbaum D. M., Hanson M. A., Rasmussen S. G., Thian F. S., Kobilka T. S., Choi H. J., Kuhn P., Weis W. I., Kobilka B. K., Stevens R. C. (2007) Science 318, 1258–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Saugstad J. A., Yang S., Pohl J., Hall R. A., Conn P. J. (2002) J. Neurochem. 80, 980–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ciruela F., McIlhinney R. A. (2001) J. Neurochem. 76, 750–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dong C., Filipeanu C. M., Duvernay M. T., Wu G. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768, 853–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Morello J. P., Bichet D. G. (2001) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 607–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stojanovic A., Hwa J. (2002) Receptors Channels 8, 33–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Themmen A. P., Brunner H. G. (1996) Eur. J. Endocrinol. 134, 533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Uemura K., Kuzuya A., Shimohama S. (2004) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 1, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Narishige T., Blade K. L., Ishibashi Y., Nagai T., Hamawaki M., Menick D. R., Kuppuswamy D., Cooper G., 4th (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9692–9697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sato H., Nagai T., Kuppuswamy D., Narishige T., Koide M., Menick D. R., Cooper G., 4th (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 963–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]