Abstract

Transcription, the synthesis of RNA from a DNA template, is performed by multisubunit RNA polymerases (RNAPs) in all cellular organisms. The bridge helix (BH) is a distinct feature of all multisubunit RNAPs and makes direct interactions with several active site-associated mobile features implicated in the nucleotide addition cycle and RNA and DNA binding. Because the BH has been captured in both kinked and straight conformations in different crystals structures of RNAP, recently supported by molecular dynamics studies, it has been proposed that cycling between these conformations is an integral part of the nucleotide addition cycle. To further evaluate the role of the BH, we conducted systematic alanine scanning mutagenesis of the Escherichia coli RNAP BH to determine its contributions to activities required for transcription. Combining our data with an atomic model of E. coli RNAP, we suggest that alterations in the interactions between the BH and (i) the trigger loop, (ii) fork loop 2, and (iii) switch 2 can help explain the observed changes in RNAP functionality associated with some of the BH variants. Additionally, we show that extensive defects in E. coli RNAP functionality depend upon a single previously not studied lysine residue (Lys-781) that is strictly conserved in all bacteria. It appears that direct interactions made by the BH with other conserved features of RNAP are lost in some of the E. coli alanine substitution variants, which we infer results in conformational changes in RNAP that modify RNAP functionality.

Keywords: Gene Expression, RNA Polymerase, RNA Synthesis, Transcription, Transcription Initiation Factors, RNA Cleavage

Introduction

Multisubunit RNA polymerases (RNAPs)3 function as complex molecular machines that are central to regulated gene expression in all cellular organisms (1–3). Multiple conformational changes accompany and are required for the action of RNAP. These can be modulated in magnitude and frequency by control factors that act as regulatory signals. The catalytically competent core enzyme (α2ββ′ω; in bacteria) is highly conserved across all domains of life in its ternary structure and sequence (1–4). The acquisition of high resolution structures of RNAPs and their complexes from bacteria, yeast, and archaea, coupled with biochemical and biophysical analyses of RNAP domain functionalities, has led to a detailed molecular level appreciation of how the enzyme functions in promoter recognition, transcription initiation, elongation, and pausing (1, 3, 5).

One prominent conserved structural feature of RNAP is the β′ bridge helix (BH) (see Fig. 1A), an α-helical domain that spans the active site of the enzyme (5, 6). Other conserved structural features of the RNAP active center include β fork loop 2 (FL2), which maintains the downstream edge of the transcription bubble, and the β′ lid domain, which helps maintain the upstream edge of the RNA-DNA hybrid (3, 5, 7, 8). Along with the BH, another feature of the RNAP catalytic center is the trigger loop (TL); both are involved in NTP binding and translocation and have been captured in distinctly different conformations, implying that they possess dynamic characteristics (9–15). Proposed mechanisms of the translocation event, associated with extension of the RNA chain, postulate that binding of the incoming NTP is coupled with a conformational change in the BH-TL assemblage for stepwise forward movement of RNAP (7, 9, 13, 14, 16, 17). An additional feature of the RNAP catalytic site, the β′ F-loop (also termed conserved region β′a15) (3), has also been demonstrated to play an essential role (alongside the BH and TL) in catalysis by bacterial RNAPs (18). Several RNAP-interacting factors function through or with the BH and TL. The phytotoxin tagetitoxin binds in the vicinity of the active center, inhibiting RNAP elongation (19) potentially by restricting movements of the BH and TL. Streptolydigin binds to the BH and interferes with the nucleotide addition cycle, thereby inhibiting RNAP activity (11, 20). Furthermore, the transcript cleavage factor Gre appears to assist in RNAP backtracking and stimulates RNA cleavage via the BH and TL (21–24).

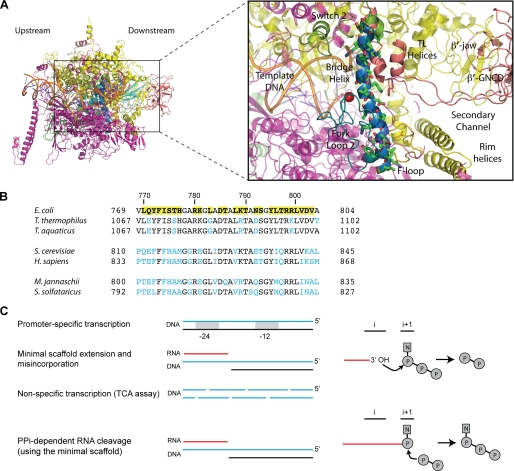

FIGURE 1.

RNAP BH. A, atomic model of E. coli RNAP (Protein Data Bank code 3LU0) (27) viewed into the secondary channel, colored as follows: α subunits (green/cyan), β (magenta), β′ (yellow), ω (light pink), active site Mg2+ (red sphere), and RNA-DNA hybrid (orange). The gray box contains a close-up of the BH and surrounding motifs colored as follows: BH (dark blue), TL/TL helices (dark pink), FL2 (teal), and switch 2 (olive green). Also labeled are the β′-jaw, F-Loop, β′-G recovered domain (β′-GNCD). The BH residues targeted in this study (green sticks) are indicated. Upstream and downstream faces of RNAP are labeled. B, sequence alignment of representative BH sequences from bacteria (E. coli K12, T. thermophilus, and Thermus aquaticus), archaea (M. jannaschii, and Sulfolobus solfataricus), and eukaryotes (S. cerevisiae and Homo sapiens). The mutated residues in E. coli are highlighted by yellow boxes. Blue lettering indicates where the sequence differs from the mutated E. coli residues. The M. jannaschii sequence numbering is based on the intein-free final product. C, schematic representation of the catalytic activities monitored in this study (adapted from Ref. 5). i and i+1 represent the product and substrate-binding sites of the catalytic center, respectively. Solid red lines represent the nascent RNA, and curved arrows indicate the direction of nucleophilic attack. P and N refer to phosphate and nucleotide residue, respectively.

Mutating residues in the BH can result in fast (F773V in Escherichia coli) (25) or “super-active” (S824P in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii) (26) variants of RNAP. To gain further insights into the contributions the BH makes to RNAP activities, we conducted comprehensive alanine scanning mutagenesis of the BH feature of E. coli RNAP (see Fig. 1B). Mutants were assayed for (i) promoter-specific (i.e. σ-dependent), (ii) nonspecific promoter-independent, and (iii) specific (RNA primer-dependent) promoter-independent transcription activities (see “Experimental Procedures” and Fig. 1C), as well as effects on in vivo growth. Taken together, our results generate a comprehensive activity map of the E. coli RNAP BH (see Fig. 2). A number of residues important for transcript formation were identified. Inspection of an atomic model of E. coli RNAP (Protein Data Bank code 3LU0) (27) determined that altered interactions between the BH and (i) the TL, (ii) the F-loop, (iii) FL2, and/or (iv) switch 2 of RNAP may be linked to the observed defects (in the BH alanine substitution mutants). In particular, lysine at position 781, which is invariant in bacteria, appears to be essential in all of the in vitro activities tested. The BH variants that fail in elongation and pyrophosphate-mediated RNA cleavage harbor potential defects in the catalytic activity used for RNA synthesis. BH variants that display significantly reduced in vivo growth activities (in contrast to their observed in vitro activities) could display defects not directly tested by our in vitro assays, e.g. promoter pausing. Finally, two BH variants (V801A and D802A) exhibited severely impaired minimal scaffold-binding activities; we infer that these represent forms of RNAP in which the clamp domain may adopt a more closed conformation.

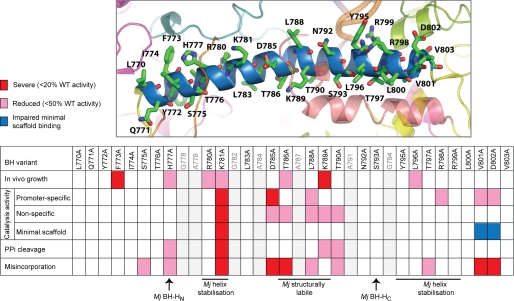

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the activities of the BH variants. Upper, atomic model of the E. coli BH with positions of the residues mutated in this study indicated. Lower, summary table listing the activities of the BH variants obtained using the assays performed in this study. Red designates severe (<20% of WT activity) defects, pink indicates reduced activity (<50% of WT activity), and blue denotes impaired minimal scaffold binding. The gray lettering refers to residues not mutated in this study. Sites in the M. jannaschii (Mj) BH denoted as the N- and C-terminal hinge regions (BH-HN and BH-HC, respectively), required for helix stabilization or to be structurally labile, are also shown (26, 39, 49).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutagenesis of E. coli rpoC

Single alanine substitutions of amino acids 770–803 (except residues that were already alanine or glycine) of the E. coli rpoC gene (pIA661) were introduced using QuikChangeTM (Agilent Technologies). The complete rpoC gene was reconstituted in pVS10 (a gift from I. Artsimovitch) (28) by replacement cloning of an MsnI-HindIII fragment. The pVS10 construct encodes the E. coli rpoA-rpoB-rpoC-His6 and rpoZ ORFs under the control of the T7 promoter. Recombinant plasmids were verified by sequencing.

In Vivo Growth Complementation

E. coli strain EC397c (29) has a temperature-sensitive rpoC allele that fails to grow at 43.5 °C. Growth complementation of this strain was performed using the rpoC BH variants expressed from pVS10 in strain EC397c(DE3) (formed by infecting EC397c with λDE3 using a λDE3 lysogenization kit (Novagen) following the manufacturer's guidelines). Cells for growth curves were cultured overnight in LB medium at 30 °C and used to inoculate fresh medium at an A600 of ∼0.01. Replicates were incubated at 30 and 43.5 °C, and growth was monitored every 2 h (for the first 8 h) by apparent absorbance at 600 nm.

DNA Probes and Proteins

The Sinorhizobium meliloti nifH DNA probes (Sigma) used in the small primed RNA (abortive transcription) assays and promoter complex formation assays were 5′-32P-labeled (where appropriate) and annealed to the complementary strand as described (30). E. coli RNAP (WT and BH variants), PspF(1–275), and Klebsiella pneumoniae σ54 were overexpressed in E. coli and purified as described (30–32). E. coli σ70 was purified as described (33).

Transcription Assays (see Fig. 1C)

Promoter-dependent transcription assays were performed in STA buffer (25 mm Tris acetate (pH 8.0), 8 mm magnesium acetate, 10 mm KCl, and 3.5% (w/v PEG) 6000) in a 10-μl reaction volume containing 100 nm σ54/RNAP or σ70/RNAP (reconstituted using a 1:4 ratio of core RNAP (WT or variants) to σ) and 20 nm promoter DNA probe. For full-length assays, a supercoiled plasmid containing the S. meliloti nifH promoter (pMKC28) was used. For small primed RNA (abortive) assays, either the supercoiled plasmid pMKC28 or a linear probe composed of positions −60 to +28 of the S. meliloti nifH promoter that was mismatched between positions −10 and −1 (believed to mimic the state of the promoter within the open complex) (34) was used as described (35). (For σ70-dependent assays, the supercoiled lacUV5 promoter was used (33).) Open promoter complexes were formed by adding 4 μm PspF(1–275) and 4 mm dATP to the reaction. All reactions were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C prior to addition of an elongation mixture. Synthesis of the full-length product was initiated by adding a mixture containing 100 μg/ml heparin; 1 mm ATP, CTP, and GTP; 0.05 mm UTP; and 3 μCi of [α-32P]UTP. Synthesis of the abortive product (UpGGG) was initiated by addition of a mixture containing 100 μg/ml heparin, 0.5 mm UpG, and 4 μCi of [α-32P]GTP. Both sets of reactions were incubated at 37 °C for a further 20 min. Reactions were quenched by addition of loading buffer, and full-length and abortive transcripts were analyzed on 6 and 20% denaturing gels, respectively. All transcripts were visualized and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 PhosphorImager. Transcription assays were performed at least three times, and activation time points were specifically chosen to be within the linear range of this assay (36).

Specific promoter-independent transcription assays were performed using a minimal scaffold template that was constructed by first annealing the DNA strands 5′-GGTCCTGTCTGAAATTGTTATCCGCTAC (template) and 5′-ACAATTTCAGACAGGACC (non-template) to which a priming RNA molecule either 7 bases (5′-GUAGCGG) or 8 bases (5′-GUAGCGGA) in length was annealed (similar to Refs. 7 and 18). Promoter-independent transcription assays used 100 nm minimal scaffold assembly and were conducted in STA buffer. RNA synthesis was initiated by addition of 100 nm core RNAP (WT or BH variants) and 4 μCi of [α-32P]UTP. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and quenched by addition of loading buffer, and products were analyzed on 20% denaturing gels. Products were visualized and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 PhosphorImager. All minimal scaffold assays were performed at least three times within the linear range of the assay, and the data were normalized to account for differences in minimal scaffold-binding affinities.

Nonspecific promoter-independent transcription (TCA precipitation) assays were conducted essentially as described (26) using sonicated calf thymus DNA as a template except that the reaction temperature was lowered from 70 to 37 °C. Activity was measured by recording the amount of TCA-precipitated counts arising from the incorporation of [α-32P]UTP. All TCA assays were performed at least three times.

Minimal Scaffold-binding Assays

Assays were conducted in STA buffer using a minimal scaffold template (see above) in which the RNA was 5′-32P-labeled (see above) and 100 nm core RNAP (WT or BH variants). Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and quenched by addition of native buffer, and products were analyzed on 4.5% nondenaturing gels. Products were visualized and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 PhosphorImager. All binding assays were performed at least three times.

Pyrophosphorolysis (PPi) Assays

Assays used 100 nm minimal scaffold assembly with a 32P-labeled 7-nucleotide RNA primer. Assays were conducted in STA buffer using 100 nm core RNAP (WT or BH variants) and 5 μm PPi (Na4O7P2·10H2O; Sigma). Reactions were then incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and quenched by addition of loading buffer, and products were analyzed on 20% denaturing gels. Products were visualized and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 PhosphorImager. All PPi experiments were performed at least three times, and the data were normalized to account for differences in minimal scaffold-binding affinities. Importantly, the 10-min time point coincides with ∼40% PPi-catalyzed cleavage by WT RNAP and as such is within the linear range of this assay.

Misincorporation Assays

Assays used 100 nm minimal scaffold assembly with 32P-labeled 8-nucleotide RNA primer. Assays were conducted in STA buffer using 100 nm core RNAP (WT or BH variants) and 2 mm nucleotide extension mixtures that lacked a single nucleotide (as indicated). Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and quenched by addition of loading buffer, and products were analyzed on 20% denaturing gels. Products were visualized and quantified using a Fuji FLA-5000 PhosphorImager. All misincorporation assays were performed at least three times within the linear range of the assay, and the data were normalized to account for differences in minimal scaffold-binding affinities.

Structural Analysis

We used the atomic model of E. coli RNAP (Protein Data Bank code 3LU0) (27) to guide our interpretation of the activity data sets. All structural interpretations and figures were produced using PyMOL (Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger LLC).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

E. coli BH

To uncover the roles of the E. coli RNAP BH, we constructed single alanine substitution mutants comprising residues 770–803 (omitting positions that were naturally either alanine or glycine, generating 27 variants in total) (Fig. 1B). Alanine substitutions provide evidence of potentially important side chain interactions made by the BH. Such interactions may be involved in one or more of the following: σ54 factor-dependent promoter recognition, DNA melting, and RNA synthesis. We specifically choose σ54 because it allows the holoenzyme, closed complex, and open complex and their associated activities to be readily assessed. The effects of the BH variants on the aggregated outcomes of the following RNAP activities were then examined in vitro: (i) promoter-dependent/independent DNA binding and melting, (ii) nucleotide addition and phosphodiester bond formation (i.e. catalysis), (iii) translocation of RNAP along the DNA, (iv) translocation of RNA to the i+1 site, (v) minimal scaffold binding, and (vi) phosphodiester bond cleavage (Fig. 1C). The functionality of the mutant RNAPs was also measured in vivo by examining growth complementation of the E. coli strain EC397c at 43.5 °C (see “Experimental Procedures” and supplemental Fig. S1). Transcription defects were scored as severe if displaying <20% of WT activity and classified as reduced with ∼50% of WT levels.

Current crystal structures of bacterial RNAPs indicate that the BH makes direct interactions with a number of conserved RNAP features, namely the TL, FL2, the F-loop, and switch 2. Using an atomic model of E. coli RNAP (Protein Data Bank code 3LU0) (27), we provide possible explanations for the defects associated with the BH alanine mutants. Substitution of certain BH residues with alanine is proposed to result in disruption of interhelix interactions, as well as interactions with other conserved features of RNAP, which we infer leads to an altered conformation or a change in the normal distribution of conformations of RNAP and hence loss of (some) functionality (Fig. 2) (26, 37–39).

Silent Mutations

Of the 27 alanine substitutions studied, nine (L770A, Q771A, Y772A, L783A, N792A, S793A, Y795A, R798A, and R799A) displayed no significant transcription defects (>50% of WT activity levels) in vivo and in vitro under the experimental conditions used here (Fig. 2 and supplemental Figs. S1–S5). Leu-770, Gln-771, and Tyr-772 are located at the N terminus of the BH, proximal to the β subunit but do not appear to directly interact with any motifs recognized as being critical for transcription. Tyr-795, Arg-798, and Arg-799 are located toward the C-terminal end of the BH, and at least one residue, Arg-798, has been proposed to interact with the template strand at +2 (1–3). Nonspecific promoter-independent transcription assays, which measure RNA synthesis, demonstrated that a positively charged side chain at Arg-829 (M. jannaschii), corresponding to Arg-798 (in E. coli), was highly sensitive to mutagenesis in RNAP from M. jannaschii (26). However, we observed ∼55% of WT activity for R798A in the nonspecific assay (see “Experimental Procedures” and supplemental Fig. S2). This assay measures RNA synthesis in the absence of (i) a single defined (minimal scaffold) template and (ii) the stringency associated with the correct placement of the 3′-end of the RNA primer within the active site (of RNAP). The basis for the observed discrepancy in activity may result from differences in (i) the temperature at which the reactions were conducted, which could impact on the tolerance to different amino acid side chains at a particular position, and/or (ii) distinct ranges of co-dependences between the BH and TL in M. jannaschii versus E. coli. Potentially, the activity difference could arise from the particular amino acid residue immediately N-terminal to this position. We note that the residue immediately N-terminal to Arg-798, Thr-797, is invariant among bacterial species, whereas in archaea and eukaryotes, this residue is often glutamine. Furthermore, the different side chains at this site could impact on the outcomes of substituting the adjacent conserved arginine. In line with this suggestion, Arg-799 tolerates a range of amino acid substitutions, similar to Arg-830 in M. jannaschii (supplemental Fig. S2) (26).

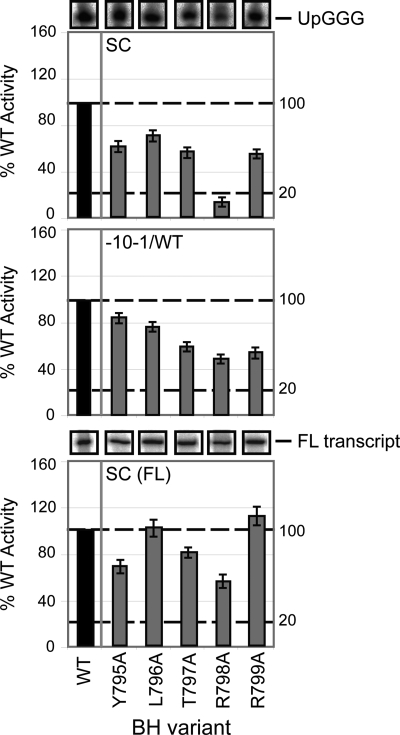

Interestingly, R798A exhibited reduced activity in the σ54 promoter-specific small primed (abortive) RNA assay (which effectively measures the activity of stable open complexes that form) using the supercoiled template (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S2). This assay uses an elongation mixture that contains only the dinucleotide primer UpG and GTP (preventing synthesis of an RNA product longer than 4 nucleotides in length, UpGGG) (35). The activity of R798A was recovered by pre-opening the template (between positions −10 and −1, which mimics the state of DNA within the open complex) (34) or by addition of the full-length elongation mixture, permitting synthesis of the full-length transcript product (Fig. 3). Given the observation that the effect of the R798A substitution was less evident in (i) full-length σ54-dependent transcription (when the RNA-DNA hybrid is longer than 4 nucleotides) or (ii) when the promoter DNA was pre-opened, we infer that Arg-798 is required to stabilize the transcription bubble prior to elongation, when only a short RNA-DNA hybrid is present, consistent with the observation that Thermus thermophilus Arg-1096 interacts with +2 of the template strand (3).

FIGURE 3.

Promoter-dependent transcription activities of BH residues 795–799. The bar graphs depict the relative intensities (expressed as a percentage of WT RNAP activity, where WT = 100%) of the σ54-dependent products formed on the supercoiled (SC; upper panel), pre-opened (mismatched between positions −10 and −1 (−10−1/WT); middle panel) and supercoiled (full-length transcripts (FL); lower panel) templates in the presence of the BH variants Y795A, L796A, T797A, R798A, and R799A. Gel slices of the corresponding small primed RNA (UpGGG) and full-length (FL transcript) products (obtained using the supercoiled template) are shown above the respective bar graphs. Black bars represent WT (100%) activity. All assays were performed at least three times, and S.D. values are shown.

FL2 Interactions

FL2 is an highly conserved motif that appears to maintain the downstream edge of the transcription bubble, interfering with the non-template strand upstream of position +3 and thus sterically preventing reannealing of the DNA strands (3, 7, 8, 10, 40). The N-terminal region of FL2 forms an extensive hydrophobic interface with the β pincer (particularly the downstream lobe), which serves to increase the ability of RNAP to translocate following nucleotide addition (13). Numerous structures (including the E. coli model) position the N-terminal region of the BH (residues 773–780) in close proximity to FL2.

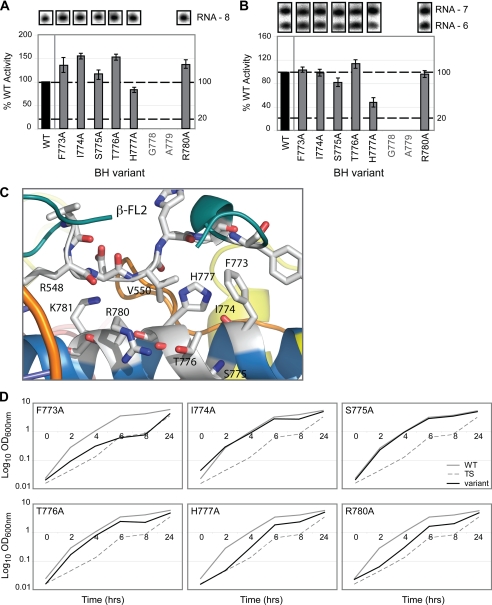

Using a nonspecific primer-dependent transcription assay (Fig. 4A) and a pyrophosphorolysis (PPi)-catalyzed RNA cleavage (of the 3′-end of RNA) assay (Fig. 4B), we measured nucleotide addition (catalysis/polymerization) and hydrolytic cleavage (the reverse of the polymerization reaction) in artificially assembled elongation (minimal scaffold) complexes to provide an indication of the catalytic activity of the mutant RNAPs. Of the mutants proposed to interact with FL2 (Fig. 4C), only H777A exhibited reduced PPi-dependent cleavage activity (∼50% of WT levels) (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. S3). These assays were performed using a previously characterized minimal scaffold template (7, 18); however, further activity differences might be revealed if the PPi assays were conducted in other contexts (i.e. fully complementary scaffolds). Because His-777 is located some distance (>20 Å) from the active center Mg2+ ion, we reasoned that the H777A mutation could result in changes in the interhelix interactions within the BH or the surrounding RNAP features, negatively impacting on the organization of the catalytic site for RNA cleavage and/or correct presentation of the 3′-RNA. In line with this observation, the residue equivalent to His-777 in M. jannaschii, Met-808, was found to be super-active when mutated to a variety of other amino acids. Met-808 was therefore proposed to be the site of a molecular hinge, where kinking at this position would result in localized changes in the BH interhelix interactions, length, flexibility, and topology (39). Furthermore, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the equivalent of His-777, His-816, constitutes a binding target for the transcription inhibitor α-amanitin, indicating that this residue is important for α-amanitin binding and may be the route through which α-amanitin exerts its action (41).

FIGURE 4.

Proposed FL2 interactions with BH residues 773–780. A, bar graph depicting the activities of the BH variants (F773A, I774A, S775A, T776A, H777A, and R780A) expressed as a percentage of WT activity (where WT = 100%) in the specific promoter-independent minimal scaffold extension assay (using a minimal scaffold with an RNA-DNA hybrid length of 7 nucleotides; RNA-7). Gel slices of the corresponding RNA (RNA-8) product formed after incorporation of [α-32P]UTP are shown above the bar graph. B, activities of the same BH variants in the PPi-catalyzed RNA cleavage assay (using the same minimal scaffold as in A). Gel slices of the corresponding RNA products (RNA-6) formed after PPi-catalyzed cleavage (of RNA-7) are shown above the bar graph. C, structural relationship between BH (blue) residues 773–780 and FL2 (teal) (derived from the E. coli atomic model (Protein Data Bank code 3LU0)) (27), with E. coli numbering. D, growth curves depicting the effect of the BH variants (see above) on growth complementation. Gray solid lines represent WT RNAP (i.e. wild-type RpoC), gray dashed lines represent the temperature-sensitive strain alone (TS; i.e. no plasmid-encoded RpoC present), and black lines represent the BH variants. In A and B, black bars indicate WT (100%) activity, and gray lettering refers to residues not mutated in this study. All assays were performed at least three times, and where appropriate, S.D. values are shown. Assays performed using the minimal scaffold template have all been normalized to account for differences in minimal scaffold binding.

Interestingly, a significant in vivo growth defect was observed with the F773A variant (and to some extent, reduced growth activities of H777A and R780A) (Fig. 4D and supplemental Fig. S1). Western blot analysis confirmed that F773A was (i) expressed and (ii) catalytically active at 43.5 °C (supplemental Fig. S1), thereby eliminating gross protein instability as a basis for the observed growth defect. Promoter-specific in vitro full-length transcription assays performed in the presence of σ70 showed no loss of elongation activity (supplemental Fig. S1). However, it has previously been observed that the F773V mutant results in a fast form of RNAP that displays pause-free RNA chain extension (25). Given this observation, we reasoned that the in vivo defect associated with the F773A variant may also result from altered pausing/chain extension activities in vivo.

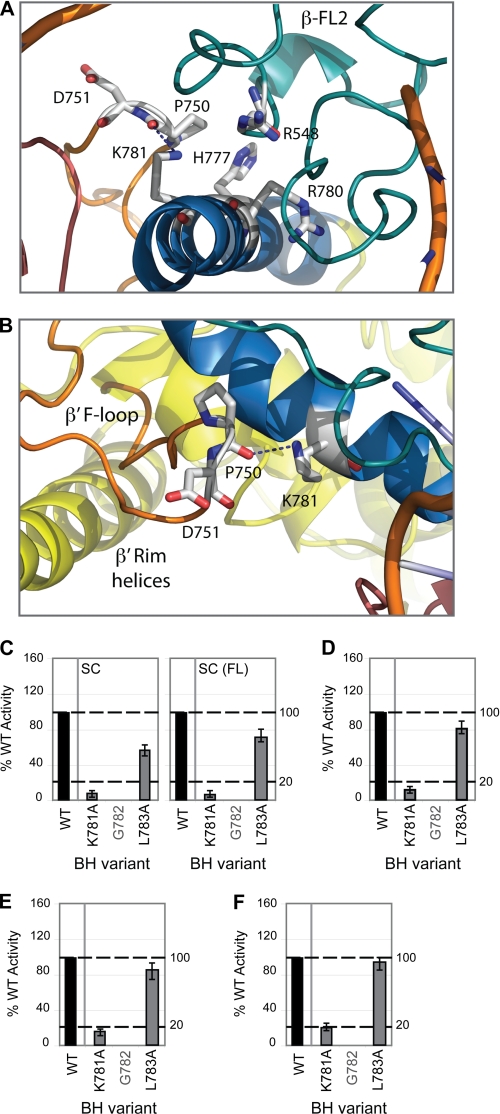

Role of Lys-781 in the E. coli BH

The strongest in vitro defects were observed with the K781A variant (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S2–S4). According to studies on the M. jannaschii BH, Lys-781 is located within a segment of the BH proposed to be flexible (between Gly-778 and Leu-783), located some distance from the site of promoter DNA binding (Fig. 5A) and potentially interacting with the F-loop via Pro-750 and other domains such as β D-loop II. The F-loop is located between the secondary channel rim helices and the N terminus of the BH (Fig. 5B) (3). It has been proposed that this flexible region (778GARKGL783) undergoes spontaneous kinking, particularly around the glycine residue(s), which have low α-helix-forming propensity (38, 39). This “kinked” conformation is stabilized through noncovalent interhelix interactions potentially via Lys-781. Recent studies strongly suggest that the BH operates through being “flexible” at certain hinge regions (potentially centered at Gly-778 or Gly-782), enabling the BH to kink during the nucleotide addition cycle (37–39). Given that alanine has a similar helix-forming propensity as lysine, we do not envisage the K781A mutation impacting on the local α-helical nature of the BH (42). In line with these observation, we infer that the severely reduced RNA synthesis and cleavage activities associated with the K781A variant (Fig. 5, C–F), may arise from the K781A mutation disrupting the interhelix (and F-loop) interactions made by the lysine side chain and thereby impacting on the conformation of the BH (37–39). An altered conformation of the BH in this region would be expected to impact upon interactions with adjacent RNAP domains such as β D-loop II and the F-loop. Because the F-loop appears to have no discernable effect on RNA cleavage (18), we infer that the PPi-associated defects observed for K781A are due to altered interactions with β D-loop II, which is in direct contact with the 3′-end of the nascent transcript. Differences observed in the nucleotide addition activity of the K781A variant in the misincorporation assays (supplemental Fig. S4) versus minimal scaffold extension assays (supplemental Fig. S2) may be due to the different nucleotide concentrations used or the placement of the 3′-end of the RNA primer with respect to the active site residues of RNAP.

FIGURE 5.

Proposed role of Lys-781, an invariant lysine in bacterial RNAPs. A and B, atomic models of E. coli RNAP depicting the structural relationship between BH (blue) Lys-781, TL helices (dark pink), FL2 (teal), the β′ F-loop (orange), and β′ rim helices (yellow). Interactions are indicated by dashed lines. C, bar graph showing the relative intensities (where WT = 100%) of the σ54-dependent (abortive and full-length (FL)) RNA products formed on the supercoiled (SC) template with BH variant K781A. D, relative activity of BH variant K781A in the nonspecific promoter-independent transcription (TCA) assay (expressed as a percentage of WT activity). E, relative activity of K781A in the specific promoter-independent transcription (minimal scaffold extension) assays expressed as a percentage of WT activity (using a minimal scaffold template with a RNA-DNA hybrid length of 8 nucleotides; RNA-8). F, relative activity of K781A in the PPi cleavage assay expressed as a percentage of WT activity. In C–F, black bars indicate WT (100%) activity, and gray lettering refers to residues not mutated in this study. All assays were performed at least three times, and S.D. values are shown. Assays performed using the minimal scaffold template have all been normalized to account for differences in minimal scaffold binding.

TL Interactions

The TL makes a number of specific interactions with the BH along an extensive generally hydrophobic interface (Fig. 6A). A number of BH residues studied here (Asp-785–Thr-790) have the potential to disrupt this interface, thereby impairing TL functionality. Interestingly, molecular dynamics studies identified this region (in particular, residues 786–789) as structurally labile, implying that these residues might contribute to interhelix interactions that directly impact upon the structural flexibility of the BH (in this region) (38, 39).

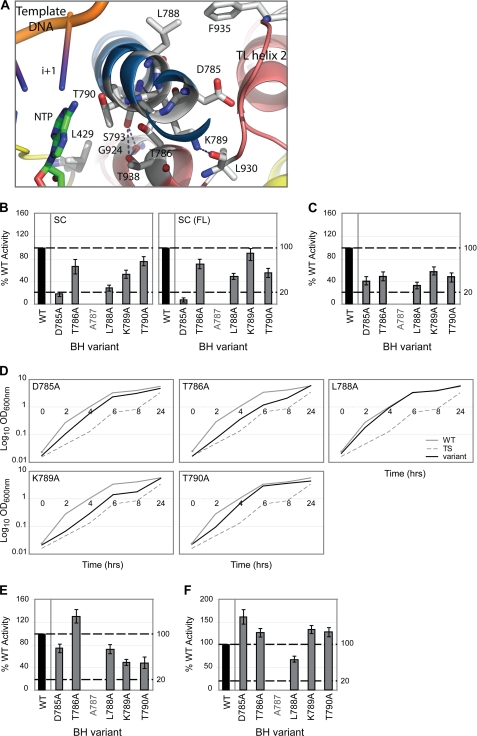

FIGURE 6.

Proposed TL interactions with BH residues 785–790. A, atomic model of E. coli RNAP depicting the structural relationship of BH (blue) residues 785–790, TL helices (dark pink), template DNA, and incoming nucleotide (NTP), with polar contacts indicated by dashed lines. B, bar graphs show the relative intensities (where WT = 100%) of the RNA products (abortive and full-length (FL) transcripts) formed on the supercoiled (SC) template in the presence of BH variants D785A, T786A, L788A, K789A, and T790A. C, activities of the same BH variants in the nonspecific promoter-independent transcription (TCA) assays (expressed as a percentage of WT activity). D, growth curves depicting the effect of these BH variants on growth complementation. Gray solid lines represent WT RNAP (i.e. wild-type RpoC), gray dashed lines represent the temperature-sensitive strain alone (TS; i.e. no plasmid-encoded RpoC present), and black lines represent the BH variants. E, relative intensities of the above BH variants in the PPi cleavage assay (using a minimal scaffold with an RNA-DNA hybrid length of 7 nucleotides; RNA-7) expressed as a percentage of WT activity. F, activities of the above BH variants in specific promoter-independent transcription (minimal scaffold extension) assays (using the same minimal scaffold as in E). In B, C, E, and F, black bars indicate WT (100%) activity, and gray lettering refers to residues not mutated in this study. All assays were performed at least three times, and S.D. values are shown. Assays performed using the minimal scaffold template have all been normalized to account for differences in minimal scaffold binding.

D785A exhibited severely reduced (<20% of WT activity) σ54 promoter-specific transcription activity (Fig. 6B). Control reactions addressing the effect of the D785A mutation on σ54-associated activities implied that the BH did not contribute to σ54 binding or promoter complex formation (supplemental Fig. S5), suggesting that the observed defects are not due simply to altered σ54-dependent interactions. The D785A variant also showed reduced nonspecific transcription (Fig. 6C) and misincorporation (supplemental Fig. S4) activities. Asp-785 is positioned close to the TL interface but is not known to make a direct interaction with the TL. Similar to D785A, T786A exhibited reduced nonspecific promoter-independent transcription (Fig. 6C) and altered misincorporation (supplemental Fig. S4) activities. L788A, akin to D785A, exhibited reduced σ54 promoter-specific (Fig. 6B) and nonspecific promoter-independent (Fig. 6C) transcription activities, as well as altered misincorporation activities (supplemental Fig. S4). Lys-789 has been shown to undergo large conformational movement upon TL folding (8) and, according to the atomic model, interacts with Leu-930 of the TL (Fig. 6A). K789A exhibited impaired in vivo growth (Fig. 6D), which was not due to gross protein instability, inactivity at 43.5 °C, or σ70-associated in vitro transcription defects (supplemental Fig. S1), and reduced (∼50% of WT activity) PPi activity (Fig. 6E), which we suggest is due to altered interactions with Leu-930 that disfavor TL folding. T790A also exhibited reduced PPi cleavage activity (Fig. 6E), possibly resulting from altered interactions with the incoming nucleotide (at the i+1 site) (3).

The minimal scaffold template resembles an artificial elongation complex in which the position of the transcription bubble and the 3′-end of the nascent RNA strand is predefined. Notably, the activity of the majority of the residue 785–790 variants was recovered in the minimal scaffold extension assays (Fig. 6F). Given this observation, we suggest that residues 785–790 could be involved in (i) translocating the 3′-end of RNA in the absence of the cognate incoming rNTP or (ii) aligning the incoming nucleotide for phosphodiester bond formation. Given that molecular dynamics and M. jannaschii saturation mutagenesis studies have identified residues 786–789 as a structurally labile region, the defects associated with the BH variants (Asp-785–Thr-790) may result in altered interhelix interactions that directly impact upon the conformation of the BH and hence the interactions it makes with the TL and nascent RNA.

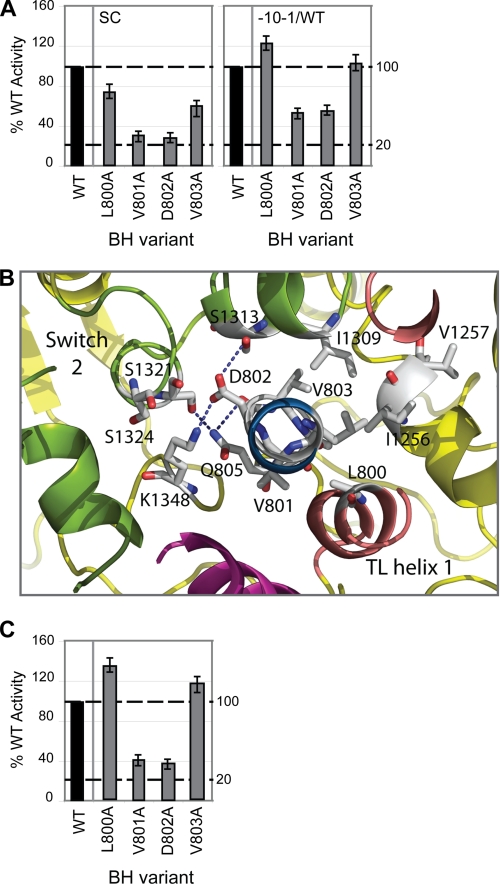

Switch Region Interactions

Mutating BH residues 800–803 resulted in altered σ54 promoter-specific transcription (Fig. 7A) and misincorporation (supplemental Fig. S4) activities. The promoter-specific transcription defects associated with V801A and D802A were partially rescued by pre-opening the DNA (Fig. 7A), implying that these mutations may result in altered interactions between RNAP and the promoter DNA during DNA melting. Interestingly, these residues form part of an extensive hydrophobic interface with the RNAP switch regions (located at the base of the clamp domain) (3, 9, 10, 17). The switch regions act as a hinge, enabling clamp movement during transcription initiation (9, 10, 17). Consequently, the switch regions adopt different conformations relating to the open and closed clamp conformational states. Several residues in switch 2 have been shown to directly interact with DNA phosphates in the elongation complex (8, 10). Furthermore, switch 2 has been identified as the binding site for the antibiotics myxopyronin (43, 44) and lipiarmycin (45). In light of these observations, it has been suggested that the role of switch 2 is to act as a molecular checkpoint for DNA loading in response to regulatory signals (43).

FIGURE 7.

Proposed switch 2 interactions with BH residues 800–803. A, bar graphs depicting the relative intensities (expressed as a percentage of WT activity, where WT = 100%) of the small primed RNA products formed on the supercoiled (SC) and pre-opened (−10−1/WT) templates obtained in the presence the BH variants L800A, V801A, D802A, and V803A. B, atomic model of E. coli RNAP depicting the structural relationship between BH (blue) residues 800–803, the TL helices (dark pink), and switch 2 (olive green), with polar contacts indicated by dashed lines. C, minimal scaffold-binding activities of the above BH variants expressed as a percentage of WT RNAP activity. In A and C, black bars indicate WT (100%) activity. All assays were performed at least three times, and S.D. values are shown.

The E. coli atomic model predicts that BH Asp-802 interacts with switch 2 via Lys-1348 and Ser-1313 (Fig. 7B). Disruption of these interactions via introduction of the alanine substitution potentially inhibits conformational rearrangements of switch 2 (communicated via the BH) necessary for clamp closure. The defects associated with the Val-801 and Asp-802 variants in terms of their implied effect on the switch regions are similar to the mechanism suggested for the transcription modifier DksA, which binds within the RNAP secondary channel and is proposed to interact with the BH and TL (46). Interestingly, variants V801A and D802A displayed impaired minimal scaffold-binding activities (Fig. 7C), which we interpret as a result of these residues impacting on the ability of RNAP to “capture” the nucleic acid template. Strikingly, mutations in RNAP II switch regions seem to phenocopy the reduced nucleic acid scaffold-binding activities observed with V801A and D802A (47). We suggest that the interface between the BH C-terminal region (residues 800–803) and switch 2 may allow the conformational state of the BH (which alternates between kinked and straight conformations during the nucleotide addition cycle) to influence the function of the clamp domain. By inference, the alanine substitutions at Val-801 and Asp-802 confer a closed configuration upon RNAP, which disfavors nucleic acid entry.

Final Comments

On the basis of the outcomes of the assays we performed, nine of the BH variants were classified as largely silent in our studies (Fig. 2). Interestingly F773A and, to some extent, K789A failed to support in vivo growth although they were (i) produced at comparable levels to WT RNAP and (ii) transcriptionally competent at the higher growth temperature (43.5 °C), implying that high temperature had no adverse effect on the stability and functionality of these variants (supplemental Fig. S1), yet they were judged to be largely competent in the in vitro assays performed here. In vivo failure of variants F773A and K789A may reflect a factor-dependent outcome not studied in vitro. Techniques employed when conducting the in vitro assays can favor strong interactions, so weaker yet important interactions that could be of significance in vivo may not be observed.

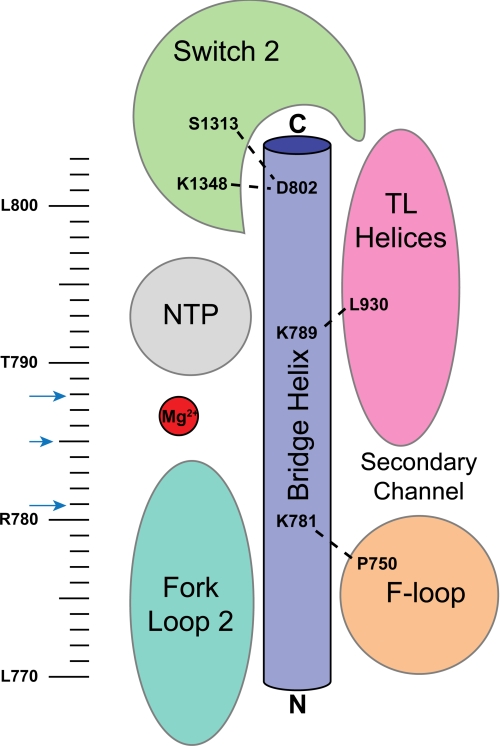

BH variants that displayed transcription defects in vitro were often proximal to or, in some cases, appeared to directly interact with important and dynamic structural features of RNAP, namely the TL, FL2, the F-loop, β D-loop II, and switch 2 (Fig. 8). The relationship between the BH and these features appears to be important for RNAP activity (Fig. 8) (3, 6, 38, 39, 48). Key BH residues include the alanine substitution at Lys-781 (the invariant lysine in bacteria), which failed in all the in vitro catalytic assays performed; D785A, L788A, V801A, and D802A, which exhibited reduced σ54 promoter-specific transcription; and V801A and D802A, which showed dramatic defects in minimal scaffold-binding activities (summarized in Fig. 8). Together, these observations serve to highlight the importance of the BH in binding and stabilizing the melted DNA template in the transcription bubble, as well as selecting and ensuring the register of the incoming rNTP. Side chain interactions made by the BH with other features of the RNAP could serve to simply organize these features or more probably participate in conformationally coupling the BH to these features (38).

FIGURE 8.

Schematic illustration of the proposed key residues/interactions arising from this study. The schematic representation of the BH and surrounding motifs is colored as follows: BH (dark blue), TL helices (pink), FL2 (teal); and switch 2 (green). The BH residues targeted in this study are indicated by the ruler. BH residues identified as potentially important for interhelix interactions are indicated by blue arrows. BH residues inferred (from this study) to interact with surrounding RNAP motifs are shown.

Multisubunit RNAPs from all cellular organisms show clear overall similarity. The active site and the nucleic acid-binding features of RNAP are highly conserved. A picture is now emerging of a set of defined interactions, centered on the BH, that link conformational changes in the active site during the nucleotide addition cycle to structural elements responsible for controlling wider RNAP functionality and RNAP interactions with promoter DNA. Interactions between the BH and the TL, FL2, the F-loop, β D-loop II and the switch regions may therefore extend beyond the architectural (and propagate, in an active sense) conformational signals to and from the active site.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the M. B. laboratory and N. Joly and F. Werner for comments on the manuscript and N. Zenkin and Y. Yuzenkova for technical advice.

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 084599/Z/07/Z and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/E00975/1 (to M. B.) and by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council David Phillips Fellowship BB/E023703/1 (to S. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5 and an additional reference.

- RNAP

- RNA polymerase

- BH

- bridge helix

- FL2

- fork loop 2

- TL

- trigger loop

- STA

- srandard transcription assay.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cramer P., Arnold E. (2009) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 680–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lane W. J., Darst S. A. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 395, 671–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lane W. J., Darst S. A. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 395, 686–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Werner F. (2008) Trends Microbiol. 16, 247–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nudler E. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 335–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Svetlov V., Nudler E. (2009) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 701–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Korzheva N., Mustaev A., Kozlov M., Malhotra A., Nikiforov V., Goldfarb A., Darst S. A. (2000) Science 289, 619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vassylyev D. G., Vassylyeva M. N., Perederina A., Tahirov T. H., Artsimovitch I. (2007) Nature 448, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cramer P., Bushnell D. A., Kornberg R. D. (2001) Science 292, 1863–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gnatt A. L., Cramer P., Fu J., Bushnell D. A., Kornberg R. D. (2001) Science 292, 1876–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tuske S., Sarafianos S. G., Wang X., Hudson B., Sineva E., Mukhopadhyay J., Birktoft J. J., Leroy O., Ismail S., Clark A. D., Jr., Dharia C., Napoli A., Laptenko O., Lee J., Borukhov S., Ebright R. H., Arnold E. (2005) Cell 122, 541–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vassylyev D. G., Sekine S., Laptenko O., Lee J., Vassylyeva M. N., Borukhov S., Yokoyama S. (2002) Nature 417, 712–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vassylyev D. G., Vassylyeva M. N., Zhang J., Palangat M., Artsimovitch I., Landick R. (2007) Nature 448, 163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang D., Bushnell D. A., Westover K. D., Kaplan C. D., Kornberg R. D. (2006) Cell 127, 941–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang G., Campbell E. A., Minakhin L., Richter C., Severinov K., Darst S. A. (1999) Cell 98, 811–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brueckner F., Cramer P. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 811–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cramer P. (2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miropolskaya N., Artsimovitch I., Klimasauskas S., Nikiforov V., Kulbachinskiy A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18942–18947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vassylyev D. G., Svetlov V., Vassylyeva M. N., Perederina A., Igarashi N., Matsugaki N., Wakatsuki S., Artsimovitch I. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 1086–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Temiakov D., Zenkin N., Vassylyeva M. N., Perederina A., Tahirov T. H., Kashkina E., Savkina M., Zorov S., Nikiforov V., Igarashi N., Matsugaki N., Wakatsuki S., Severinov K., Vassylyev D. G. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 655–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Artsimovitch I., Chu C., Lynch A. S., Landick R. (2003) Science 302, 650–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Borukhov S., Polyakov A., Nikiforov V., Goldfarb A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 8899–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Borukhov S., Sagitov V., Goldfarb A. (1993) Cell 72, 459–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nickels B. E., Hochschild A. (2004) Cell 118, 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Svetlov V., Belogurov G. A., Shabrova E., Vassylyev D. G., Artsimovitch I. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 5694–5705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan L., Wiesler S., Trzaska D., Carney H. C., Weinzierl R. O. (2008) J. Biol. 7, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Opalka N., Brown J., Lane W. J., Twist K. A., Landick R., Asturias F. J., Darst S. A. (2010) PLoS Biol. 8, e1000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Belogurov G. A., Vassylyeva M. N., Svetlov V., Klyuyev S., Grishin N. V., Vassylyev D. G., Artsimovitch I. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 117–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Christie G. E., Cale S. B., Isaksson L. A., Jin D. J., Xu M., Sauer B., Calendar R. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 6991–6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wigneshweraraj S. R., Nechaev S., Bordes P., Jones S., Cannon W., Severinov K., Buck M. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 370, 646–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Joly N., Burrows P. C., Buck M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13725–13735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joly N., Rappas M., Wigneshweraraj S. R., Zhang X., Buck M. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 66, 583–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cámara B., Liu M., Reynolds J., Shadrin A., Liu B., Kwok K., Simpson P., Weinzierl R., Severinov K., Cota E., Matthews S., Wigneshweraraj S. R. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2247–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wedel A., Weiss D. S., Popham D., Dröge P., Kustu S. (1990) Science 248, 486–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burrows P. C., Joly N., Buck M. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9376–9381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burrows P. C., Joly N., Cannon W. V., Cámara B. P., Rappas M., Zhang X., Dawes K., Nixon B. T., Wigneshweraraj S. R., Buck M. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 387, 306–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hein P. P., Landick R. (2010) BMC Biol. 8, 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seibold S. A., Singh B. N., Zhang C., Kireeva M., Domecq C., Bouchard A., Nazione A. M., Feig M., Cukier R. I., Coulombe B., Kashlev M., Hampsey M., Burton Z. F. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 575–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weinzierl R. O. (2010) BMC Biol. 8, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kettenberger H., Armache K. J., Cramer P. (2004) Mol. Cell 16, 955–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaplan C. D., Larsson K. M., Kornberg R. D. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 547–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Sousa M. M., Munteanu C. R., Pazos A., Fonseca N. A., Camacho R., Magalhaes A. L. (2010) J. Theor. Biol. 271, 136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Belogurov G. A., Vassylyeva M. N., Sevostyanova A., Appleman J. R., Xiang A. X., Lira R., Webber S. E., Klyuyev S., Nudler E., Artsimovitch I., Vassylyev D. G. (2009) Nature 457, 332–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mukhopadhyay J., Das K., Ismail S., Koppstein D., Jang M., Hudson B., Sarafianos S., Tuske S., Patel J., Jansen R., Irschik H., Arnold E., Ebright R. H. (2008) Cell 135, 295–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tupin A., Gualtieri M., Leonetti J. P., Brodolin K. (2010) EMBO J. 29, 2527–2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rutherford S. T., Villers C. L., Lee J. H., Ross W., Gourse R. L. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 236–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Majovski R. C., Khaperskyy D. A., Ghazy M. A., Ponticelli A. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34917–34923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang J., Palangat M., Landick R. (2010) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 99–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weinzierl R. O. (2010) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 428–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]