Abstract

The interaction of α-helical peptides with lipid bilayers is central to our understanding of the physicochemical principles of biological membrane organization and stability. Mutations that alter the position or orientation of an α-helix within a membrane, or that change the probability that the α-helix will insert into the membrane, can alter a range of membrane protein functions. We describe a comparative coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation methodology, based on self-assembly of a lipid bilayer in the presence of an α-helical peptide, which allows us to model membrane transmembrane helix insertion. We validate this methodology against available experimental data for synthetic model peptides (WALP23 and LS3). Simulation-based estimates of apparent free energies of insertion into a bilayer of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator-derived helices correlate well with published data for translocon-mediated insertion. Comparison of values of the apparent free energy of insertion from self-assembly simulations with those from coarse-grained molecular dynamics potentials of mean force for model peptides, and with translocon-mediated insertion of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator-derived peptides suggests a nonequilibrium model of helix insertion into bilayers.

Introduction

Interactions between α-helical peptides and phospholipid bilayers are of key importance in understanding a variety of biological and synthetic systems. Membrane proteins constitute 25% of the human genome, and individual proteins and families represent major drug targets (1,2). Certain membrane proteins are also of bionanotechnological importance (3).

Recent advances in membrane protein structural biology are revealing an exponentially increasing number of membrane protein structures (see http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html for an up-to-date summary). Experimental studies of membrane protein biosynthesis have revealed key aspects of the principles underlying biological α-helix insertion into bilayers (reviewed in, e.g., (4)). Consequently, there is much interest in understanding the physico-chemical basis of membrane protein structure and stability, and in particular in characterizing the nature of the interactions between transmembrane (TM) α-helices and their surrounding lipid bilayer environment.

Synthetic peptides designed to capture essential features of α-helices from membrane proteins have been widely used to explore peptide/bilayer interactions (5,6). These include peptides such as the WALP and KALP series which consist of a hydrophobic core of alternating alanine and leucine residues, capped at each end with tryptophan or lysine residues respectively (6–9). More recently, these model systems have been extended to include model systems in which the hydrophobic peptide acts as a host, e.g., a positively charged arginine side chain at different positions along the TM helix (10). By determining the position and orientation of such synthetic α-helices in a lipid bilayer, it has been possible to explore the effects of mismatch of peptide length and bilayer thickness (11) on TM helix stability. It has also been possible to study in detail the preference of tryptophan side chains to be located in the interfacial region of the bilayer and the ability of basic residues to “snorkel” to interact with anionic lipid headgroups, both key features of more complex membrane proteins (12,13).

Biological systems are more complex than model peptides. Biological complexity includes interactions of TM helices with their neighbors, the nature of the helix insertion machinery, and a more heterogeneous lipid environment. Recent experimental advances have permitted the assessment of the extent to which α-helices of different sequences (either designed or derived from native proteins) insert into the lipid bilayer (14–16). This is achieved by exploiting the native biological machinery (i.e., the translocon) for the insertion of peptides into a membrane. In these experiments, the sequence of interest, flanked at either end by glycosylation tags, is inserted into the sequence of the well-characterized model protein leader peptidase, Lep. By assessing the relative levels of glycosylation of these two sites, it was possible to assess the proportion of α-helix molecules which have inserted into the membrane. This technique has been used with simple designed sequences to propose a position dependent hydrophobicity scale (14), and also has been used to measure the degree of insertion of wild-type and mutant α-helices derived from channel and transporter proteins (15,17). For example, sequences derived from the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), an ABC protein containing 12 TM helices, exhibited a range of behaviors, with 3 of the 12 α-helices failing to adopt a transmembrane conformation during translocon-mediated insertion (15).

Molecular dynamics (MD) and related computer simulations may be used to explore the nature of the interactions of membrane proteins and their components with lipid bilayers (18). All-atom MD simulations have been used to catalog interactions of membrane proteins with lipids (19), and also to measure free energy profiles (or potentials of mean force, PMFs) of individual amino-acid species as a function of position in a lipid bilayer (20) and of the surrounding membrane environment (21,22). Recently, extended MD simulations have been used to define the free energy landscape for folding and insertion of a simple hydrophobic peptide into a lipid bilayer (23).

Coarse-grained (CG) MD simulations approximate the structures of lipids, water, and amino acids by mapping several (typically ∼4) atoms onto an equivalent particle (24–27). By simplification of the description of the component molecules, CG-MD enables larger and longer simulations of a given system. CG-MD simulations have enjoyed some success in understanding the behavior of lipid membranes and membrane proteins (28–37), although there has been some debate concerning their accuracy (38). It is therefore important to test CG models against available experimental data.

One approach to understanding the insertion of α-helices into lipid bilayers is to estimate the PMF for translation of the center of mass of an α-helix along the normal to a lipid bilayer. This has been studied using CG-MD for a number of model TM helix sequences (35,39) and also in a few cases has been complemented by atomistic simulations (40). In particular, recent CG-MD studies have revealed the relationship between the helix sequence (specifically hydrophobic versus amphipathic), the PMF, and the preferred location/orientation (transmembrane versus interfacial) for model helices (39).

Here we present an approach to CG-MD simulations of membrane-interacting α-helical peptides which enables us to explore in detail how peptide sequence influences α-helix insertion into a lipid bilayer. This approach uses a start-to-finish comparative protocol (named Sidekick) to automate time-consuming manual elements of the setup, running, and analysis of simulations. We validate the method via two model peptides for which extensive physico-chemical data are available, and then apply it to a survey of the TM helices from CFTR, enabling a comparison with recent data from translocon-mediated insertion experiments (15). Our results show that the sequence of a peptide specifies precisely the location of the bilayer-inserted region, and that chemical principles can be used to understand the results of in vivo experiments.

Methods

CG simulations

Coarse-grained MD simulations were performed as described previously (34) using a local modification of the MARTINI force field (28,29) (referred to hereafter as the Bond force field (35)). In both of these closely related CG approaches, a 4:1 mapping of (non-Hydrogen) atoms onto CG particles is used. Interparticle interactions were treated with Lennard-Jones interactions between four classes of particles: charged (Q), polar (P), mixed polar/apolar (N), and hydrophobic apolar (C). These were then split into subtypes to reflect differing hydrogen-bonding capabilities or polarity. In the Bond force field (35), N and Q classes were subdivided into five and four subtypes respectively to reflect hydrogen-bonding capabilities. Interactions in each case were based on a lookup table, with five levels in the Bond force field. Lennard-Jones interactions were shifted to zero between 9 and 12 Å and electrostatic interactions were shifted to zero between 0 and 12 Å.

We note that the shifting of electrostatic interactions is needed to accommodate the absence of any dielectric screening by the CG water model. This has been shown to lead to an underestimation of the free energy of burying, e.g., an arginine side chain in the bilayer center by a factor of ∼2 relative to atomistic simulations (35). This is discussed in more detail below. For these simulations, the peptide termini were treated as uncharged. Peptide α-helical secondary structure was maintained through harmonic restraints between hydrogen-bonded particles. Simulations were performed with GROMACS 3.3 (www.gromacs.org) (41,42). Temperature was coupled using a Berendsen thermostat at 323 K (τT = 1 ps), and pressure was coupled anisotropically at 1 bar (compressibility = 3 × 10−5 bar−1, τP = 10 ps). VMD (43) was used for visualization.

Simulation protocol

Peptide sequences were used to generate an ideal, atomistically detailed α-helix using standard backbone angles (ϕ = −60° ψ = −45°) and side-chain conformers. Atomistic structures were then converted to appropriate CG representations of the helix. The resultant CG representation of a helix was placed in a simulation box (90 Å × 90 Å × 90 Å) along with randomly positioned lipids, waters, and counterions. A 1000 step steepest-descent energy minimization was performed to remove any steric clashes. Self-assembly simulations of the system were performed (see (33)) to form a bilayer around the peptide while minimizing the potential sources of bias arising from the use of a preformed bilayer.

Simulation pipeline

A high throughput pipeline system, Sidekick (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material), was developed to facilitate running large ensembles of simulations in an automated fashion. These simulations were performed over a mixed computational grid consisting of a dedicated 56 core MacOS cluster and workstations. Sidekick was written in Python (http://docs.python.org/tutorial/) using the numpy and matplotlib libraries (http://matplotlib.sourceforge.net/) for calculations and plotting graphics. Xgrid (http://www.apple.com/server/macosx/technology/xgrid.html) was used to distribute calculations across the grid.

The simulation pipeline from submission of sequence to retrieval of results is entirely automated; individual simulations are built, simulated in duplicate across a dedicated cluster, monitored for crashes, analyzed, and output graphics generated (Fig. S1). This approach allows for a given ensemble of simulations to be run with multiple different initial configurations, each simulation of the ensemble being assigned to a single processor such that the overall task becomes efficiently parallel.

By default, equilibrium CG MD simulations were performed with a timestep of 20 fs. However, it is not possible to predict a priori whether this will be suitable for a given system. A range of timesteps for CG simulation have been used in the literature (from 10 to 40 fs) but we note that 20 fs has been suggested as the minimum required to maintain constant temperature and correct energy distributions. Sidekick addresses this issue by automatically monitoring whether a simulation successfully completes using a 20-fs timestep. If not, the simulation is restarted from the last recorded point using a 10-fs timestep. Velocities and coupling constants are preserved. If this occurs, the two trajectories are concatenated to give a continuous simulation for analysis. If the simulation fails using a 10-fs timestep, the system does not continue and the pipeline finishes.

Analysis

At each time point in a simulation, a helix was considered to be inserted if the tilt angle (θ, i.e., the angle between the helix axis and the bilayer-normal z) was <65° and the displacement (Δz) along the bilayer-normal of the center-of-mass of the helix relative to that of the bilayer was <10 Å. From the complete ensemble of simulations (i.e., over the total simulation time) for a given helix, the percentages of time in an inserted and a not-inserted state were measured. Then an apparent free energy of insertion was defined as

where

This definition was selected as corresponding most closely to that used to derive apparent free energies from the result of translocon-mediated insertion experiments (14), where the pattern of protein glycosylation is used to infer the %(inserted). We also note that our definition above of ΔGAPP correlated well (R > 0.9) with energies calculated simply from the total number of simulations in an ensemble in which insertion was observed.

Results and Discussion

Model peptides

WALP and LS3 insertion simulations

To evaluate the simulation methodology, we used two test systems for which extensive experimental data are available—namely, the hydrophobic α-helix WALP23 and the amphipathic α-helix LS3 (Fig. 1). Here we specifically looked to observe the well-known positional and orientational preferences of these α-helices relative to a lipid bilayer. Thus, WALP23 prefers to adopt a transmembrane orientation whereas single LS3 α-helices prefer to locate at the bilayer-water interface, parallel to the bilayer surface.

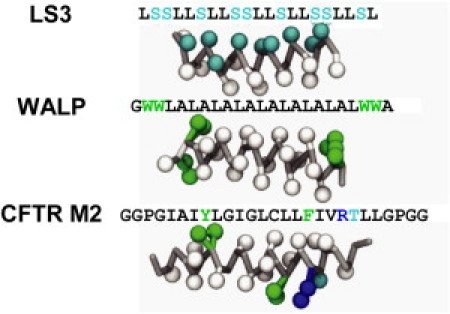

Figure 1.

Diagrams of CG structures of three α-helices used in this study: the amphipathic model peptide LS3, the hydrophobic model peptide WALP23, and a peptide derived from the M2 helix of CFTR.

The first test system, WALP23, is a model α-helical peptide consisting of a poly leucine-alanine core capped with two tryptophan residues at each end (i.e., four in total). These tryptophan residues anchor the helix in a predominantly TM orientation in the membrane (44). WALP23 has been extensively studied as a model for the interactions of lipids with peptides, and in particular the specific interactions of the hydrophobic core and interfacial region of the membrane with different residues in the peptide.

The second test system, the LS3 peptide, forms an amphipathic α-helix consisting of serine and leucine residues. At low peptide/lipid ratios in the absence of a transbilayer voltage difference, single LS3 helices adopt an interfacial orientation, parallel to the plane of the membrane (45). (When an transbilayer voltage is applied at higher peptide/lipid ratios, multiple LS3 helices can aggregate and insert into the bilayer to form ion channels (46,47)). Thus, under the conditions of our simulations, WALP23 is expected to be TM whereas LS3 is expected to adopt a non-TM orientation.

To compare the comparative approach with more conventional manual simulations of lipid-helical peptide interactions, we performed large (typically N = 200) ensembles of 100-ns simulations and compared these with smaller (N = 10) ensembles of longer (>250-ns) simulations. All simulations were carried out using DPPC. We noted that transitions from the interfacial state to the TM state did not often take place after bilayer formation, which typically occurred in the first ∼10 ns of the simulation (Fig. 2). This behavior was confirmed in extended (microsecond) simulations of helices in a bilayer which revealed the relative infrequency of transitions between interfacial and TM orientations (see Fig. S2).

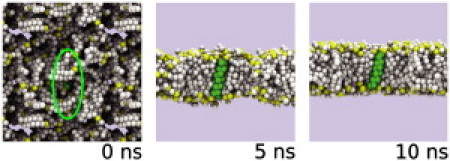

Figure 2.

The self-assembly process seen at 0, 5, and 10 ns. Lipid headgroup phosphate particles are in yellow, and the other lipid particles in white; the helix is in green. Note that CG water particles are present in the simulation but for clarity are omitted from the diagram. Initially, the lipids and waters are randomly arranged around the peptide (which is highlighted by the green ellipse), but within the first ∼10 ns, the bilayer forms and in this case (WALP23) adopts a transmembrane orientation.

To further test the convergence of the simulations, we repeated those of WALP23, LS3, and of CFTR M5 (see below) using a larger ensemble (N = 1000). These three examples represent a TM peptide, an interfacial peptide, and a helix which inserts ∼50% of the time. The results (see Table S1 in the Supporting Material) suggest that significant changes in insertion behavior are not observed when the larger ensemble is used.

Predicted orientations of WALP and LS3 relative to a bilayer agree with experiments

The simulations of LS3 and WALP23 in DPPC bilayers highlights the differences between the preferred orientations of the two peptides relative to the bilayer. WALP23 adopts a TM orientation for ∼85% of the simulations (adopting an interfacial position for the remaining ∼15%). In contrast, LS3 adopts a TM orientation for ∼20% of simulations, and an interfacial orientation for ∼80%. The results for the smaller ensembles yielded more variable results, justifying the use of the high-throughput approach.

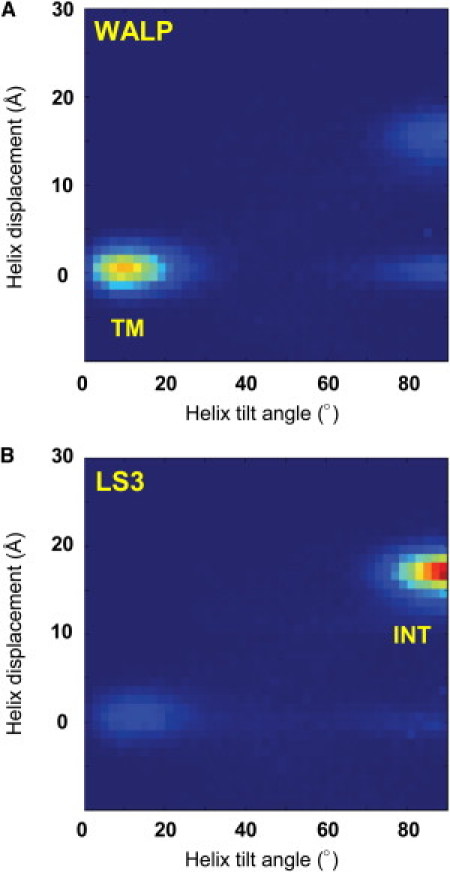

These results for WALP23 and LS3 agree well with the available experimental data. We can analyze the distributions of tilt angle (θ) and displacement (Δz) from the ensembles in more detail (Fig. 3). In the transmembrane orientation, the helix is predominantly positioned around the center of the membrane (i.e., Δz = 0), with a tilt of θ = 10°, in agreement with tilt angles observed in previously published simulation data (34). This value is consistent with atomistic simulation studies. However, comparisons between angles calculated from simulations and from solid-state NMR data have consistently differed by 10–20°. Thus, the values here differ from experimentally derived tilt angles for WALP23 in DMPC by ∼20°. However, as has been discussed by, e.g., Ozdirekcan et al. (48), this apparent discrepancy is sensitive to the method used to analyze tilt angles from quadrupolar splittings and does not seem to reflect a genuine disagreement between simulation and experiment. LS3 predominantly adopts an interfacial position (Δz = ∼17 Å), with a tilt of θ = 90°. In this location, the LS3 helix is rotated about its long axis so that the polar S side chains are directed away from the bilayer core.

Figure 3.

Helix positions and orientations for the model peptides (A) WALP23 and (B) LS3. The distributions of the displacement of the helix center relative to the bilayer along the bilayer-normal and of the helix axis tilt angle relative to the bilayer-normal derived from simulations of WALP23 and LS3 in a DPPC bilayer are shown as contour plots (blue for a zero and red for a high frequency of occurrence). The labels TM and INT indicate the transmembrane and interfacial helix locations/orientations, respectively.

It is useful to compare the self-assembly CG-MD results for WALP23 with other available experimental and computational data. From the results presented in Table 1 we obtain an estimate of ΔGAPP from −1.1 to −1.5 kcal/mol. From the translocon-mediated insertion data of Hessa et al. (14), one can estimate a ΔGAPP of ∼−4.5 kcal/mol using the DGPred server (http://dgpred.cbr.su.se/). Thus, the ΔGAPP from the CG-MD assay is of the same order of magnitude as that from experiment (albeit somewhat smaller). Turning to estimates from the CG-MD PMF (49), the ΔG for moving a WALP23 helix from the interface to a TM location is ∼−8 kcal/mol—i.e., somewhat larger than the DGPred and self-assembly values. These comparisons are extended in a more general context below.

Table 1.

Percentage of simulations in which model helices adopt a TM conformation

| Helix | Small ensemble (%) | Comparative ensemble (%) |

|---|---|---|

| WALP23 | 80 | 83 |

| LS3 | 18 | 21 |

The CG force field used was a local modification of MARTINI for insertion of peptides into bilayers (34,35). For the Small Ensemble, typically 10 simulations of duration 250 ns were run manually; for the Comparative Ensemble, typically 200 simulations of duration 100 ns were run using Sidekick.

For LS3, the comparison is a little more difficult because an experimental estimate of ΔGAPP is not available. However, a PMF is available from CG simulations (39), which suggests ΔG for moving a single LS3 helix from the interface to a TM location is ∼0 kcal/mol. Self-assembly CG-MD (Table 1) yields an estimate for ΔGAPP of ∼+0.9 kcal/mol.

Biologically complex helices: CFTR

Sidekick was used to perform simulations (an ensemble of typically 200 simulations/helix using the Bond CG force field) on a set of 20 helices based upon the predicted TM helices of the ABC protein CFTR. These are listed in Table S2. They were selected because they have been the focus of a recent study (15) in which the experimental estimates of ΔGAPP ranged from −1.4 kcal/mol (for TM9) to +1.0 kcal/mol (for TM2/−8). Thus they provided a test set to explore the performance of self-assembly CG-MD simulations in predicting α-helix insertion into a membrane for biologically realistic α-helices rather than synthetic peptide models such as WALP23 and LS3.

Although the CG method is parameterized on amino-acid side-chain membrane insertion free energies (29,35) and so might be expected therefore to reproduce such data for peptides, one might also expect both positional and nonadditive effects to occur when amino acids are combined within peptides (10,20,50). The CFTR test set allows some of these issues to be explored further.

Within an individual simulation, peptides tended to adopt a single orientation for most of the simulation time, even if the ensemble of sequences adopted an equal mix of TM and interfacial orientations. The percentage of time (across the entire ensemble) of simulations for which each of the sequences adopted a TM conformation and the corresponding free energy for insertion into a DPPC bilayer was calculated and compared with the apparent free energies for insertion determined experimentally (Fig. 4 A).

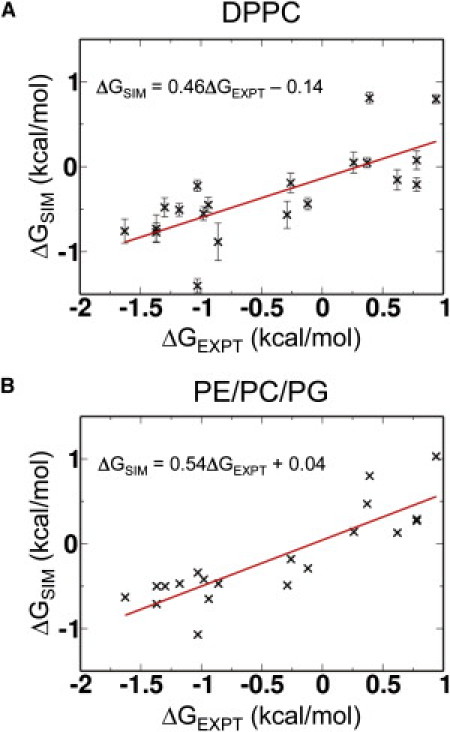

Figure 4.

Comparison of the ΔGAPP values derived from CG-MD self-assembly simulations (ΔGSIM) and from translocon-mediated insertion experiments (ΔGEXPT; data from Enquist et al. (15) for the 20 CFTR-derived peptide sequences listed in Table S1). (A) Results from simulations in DPPC. (B) Results from simulations in DPPE/DPPC/DPPG.

Our data show good agreement with the experimental values, with a correlation coefficient of 0.75. The slope of the fitted line is ∼0.5, i.e., the simulation ΔGAPP is approximately half the experimental value. Interestingly, this degree of difference has been observed between different experimental preparations (15). High percentage insertion peptides (i.e., those with a negative ΔGAPP) are generally predicted better than low percentage insertion peptides. Thus, we can conclude that the higher throughput technique for CG simulations predicts insertion behavior, particularly in terms of predicting apparent insertion energetics (see the discussion below).

Insertion behavior of CFTR α-helices in other lipids

There has been some discussion (see, e.g., (51)) of differences in TM helix length and amino-acid composition corresponding to differences in the target membrane (e.g., plasma membrane versus endoplasmic reticulum) within a cell. It is therefore of interest to explore the extent to which our CG-MD simulation results are sensitive to changes in bilayer composition.

The effect of variations in bilayer thickness on helix insertion was investigated using DLPC and DOPC bilayers. In the CG-MD simulations, the bilayer thicknesses (as defined by the distance between the phosphate particles of opposite leaflets) are 45 Å, 41 Å, and 33 Å for DOPC, DPPC, and DLPC, respectively. The CG-MD simulations show a degree of dependence on bilayer thickness, the variation in slope, and the intercept (for ΔGSIM = SΔGEXPT + I; see Table 2), indicating that bilayer insertion is somewhat more favorable for the thinner bilayer. This is of interest, because it has been argued (52) that thinner bilayers favor insertion of model TM peptides across a wide range of hydrophobic lengths. It has been reported by Yano et al. (53) that the enthalpic cost of insertion into a thicker bilayer is higher than the entropic cost of insertion into a thinner bilayer, such that helix transfer into a thicker membrane is significantly unfavorable. Furthermore, shorter hydrophobic helices tend to be observed in thinner biological membranes such as those of the Golgi apparatus (54,55).

Table 2.

Effect of alternative lipid mixes and charge states on insertion of CFTR peptides

| Lipids | Acidic side-chain charge | Slope (S) | Intercept (I) (kcal/mol) | Correlation coefficient (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC | −1 | 0.52 | +0.64 | 0.71 |

| DPPC | −1 | 0.45 | −0.13 | 0.75 |

| DLPC | −1 | 0.37 | −1.04 | 0.52 |

| DPPC/DPPG (1:1) | −1 | 0.48 | −0.09 | 0.79 |

| DPPC | 0 | 0.46 | -0.13 | 0.77 |

| DPPC/DPPG (1:1) | 0 | 0.49 | −0.09 | 0.81 |

| DPPE | 0 | 0.51 | +0.09 | 0.81 |

| DPPC/DPPG/DPPE (1:1:1) | 0 | 0.54 | +0.04 | 0.86 |

For each lipid, 200 simulations of 100-ns duration were run using the local modification of the MARTINI force field. As in Fig. 4, the line fitted was ΔGSIM = SΔGEXPT + I, where ΔGSIM is the apparent ΔG of insertion from simulation and ΔGEXPT was from the published translocon-mediated insertion experiments (15).

It has also been suggested (e.g., (56)) that the TM orientation of helices may be stabilized by the presence of anionic headgroup lipids if the helices are flanked by cationic residues. Use of a DPPC/DPPG mixed bilayer (i.e., 50% anionic lipids) resulted in a small improvement in the correlation between the simulation and experimental ΔGAPP values. We also noted the presence of glutamate residues in some of the CFTR TM helices (e.g., M1, M7, and M11). It is likely that glutamate and aspartate side chains, if inserted into a bilayer, are in a protonated state (as in, e.g., the NMR structure of the ζζ TM helix dimer (57)). Therefore we have explored CG-MD simulation in which the glutamate side chains were modeled in a neutral (i.e., protonated) state. This also resulted in a somewhat stronger correlation between simulation and experiment, the highest correlation being for a DPPC/DPPG/DPPE bilayer with neutral glutamate side chains (Table 2 and Fig. 4 B). Interestingly, this lipid composition is comparable to the composition of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane environment (58). This suggests that the CG model sensitivity to peptide-membrane interactions may be able to discriminate to some extent between different bilayer environments.

Detailed insertion behavior—insertion properties from scanning TM2

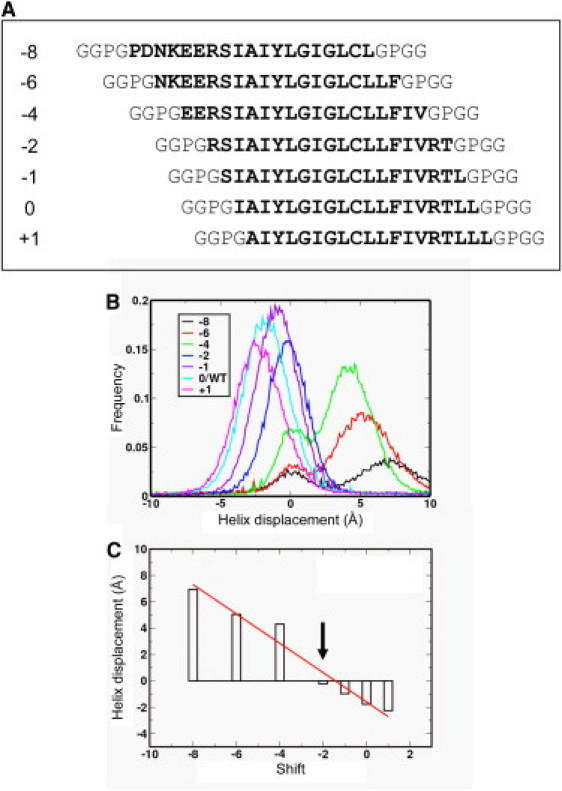

The dataset of TM helix sequences derived from Enquist et al. (15) includes a set of sequences (M2/−8 to M2/+1; see Table S1 and Fig. 5 A) corresponding to shifting a window along the length of the predicted M2 helix of CFTR. This provides an opportunity to test whether CG-MD simulations will select the start- and end-position of a possible TM helix, a limitation in the prediction of TM helices using sequence-based methods (59) if the results are to be used in subsequent structure modeling studies. Employing Sidekick, we investigate the insertion properties of this range of helices (M2/−8 to M2/+1). In the translocon-mediated insertion experiments (15) these helices showed a range of inserted frequencies (17–94%).

Figure 5.

(A) Sequences used in scanning the predicted CFTR M2 domain. The integer to the left is the shift relative to the predicted M2/0 sequence. (B) Helix displacement distributions for the M2-derived sequences. The displacement is from the center of mass of the helix backbone to the center of the bilayer along the bilayer-normal, and a positive displacement corresponds to the N-terminus of the helix being further from the bilayer center than the C-terminus. (C) The modal value of the helix displacement as a function of the sequence shift. (Indicated by the arrow) The M2/−2 helix has a zero displacement, i.e., the helix center is coincident with that of the bilayer.

Comparing the simulated and experimental insertion properties of helices from M2/−8 to M2/+1 yielded a correlation coefficient of r = 0.91, i.e., somewhat higher than from the complete set of 20 sequences. The lowest value of DGAPP was for TM2/0. Examination of the displacement of the center-of-mass of the helices relative to the bilayer as a function of the shift in sequence, relative to M2/0 (Fig. 5, B and C), revealed that M2/−2 was symmetrically placed across the bilayer (with a basic R side chain in each headgroup region). In contrast, the center of, e.g., M2/−8 was displaced by ∼7 Å, to enable positioning of the hydrophilic N-terminal sequence in contact with water. We thus may conclude that CG-MD self-assembly simulations may be used to help identify the correct location within a more complex membrane protein sequence of a bilayer-spanning helix.

Relationship to other studies

It is useful to further compare the results from the CG-MD self-assembly simulations reported in this article with those from (CG) PMFs of peptide helices calculated as a function of position along the bilayer-normal (39,49) and against experimental data from translocon-mediated insertion experiments (14,15). Approximately this may be summarized as

where ΔGPMF is the PMF-derived free energy difference for moving the peptide from an interfacial to a TM orientation. This comparison suggests two possibilities.

The first possibility is that there may be a “kinetic bias” in the CG-MD self-assembly simulations, which can result in a potentially TM helix becoming kinetically trapped at the interface and unable to penetrate the bilayer on a ∼0.5 μs timescale. (Thus, ΔGSIM would be an apparent free energy, because the process may not have reached equilibrium.) This could help to explain ΔGSIM ≈ 0.2ΔGPMF, although the insensitivity of the ΔGSIM value to an increase in ensemble size (see above) suggests this is not a major factor. A further complexity is the definition of the reaction coordinate in the PMF calculations (involving a projection of a multidimensional energy surface onto a single coordinate pathway), which may merit further exploration, especially in terms of multiple possible interfacial orientations.

The second possibility is that during translocon-mediated insertion, the partition process may also not be fully at equilibrium, but instead reflect the relative rates of transfer to the lipid bilayer (i.e., TM) relative to export through the translocon (i.e., not-TM). This would provide a possible explanation of ΔGSIM ≈ 0.5ΔGEXPT independent of considerations of the accuracy of the CG force field (29,35,38). Of course, there are other factors in the experiments difficult to capture quantitatively in such a comparison, including the conformation of the peptide when not inserted, and the nature of the environment provided to the peptide by the translocon when the TM/not-TM “decision” is made.

There has been some discussion of whether or not a more rigorous model of long-range electrostatic interactions (e.g., particle-mesh Ewald) should be included within CG simulations. For example, such long-range electrostatic interactions needs to be included to simulate pore formation in lipid bilayer induced by charged dendrimers (60,61). We therefore tested the sensitivity of our simulations to the treatment of long-range electrostatics by running insertion simulations of the CFTR M2/-2 peptide (which contains two arginine residues) and obtained apparent free energies of insertion of −0.19 and −0.16 kcal/mol without and with particle-mesh Ewald, respectively. We therefore conclude that for the peptide systems under investigation here, there is little sensitivity to the treatment of long-range electrostatics, and so elected to stay with the original MARTINI model. However, it is likely that such long-range interactions are more critical for (for example) pore formation induced by highly charged peptides, and this merits further studies in the future.

Conclusions

We have developed and evaluated a coarse-grained MD simulation method, based on self-assembly of a lipid bilayer in the presence of an α-helical peptide, which allows us to model transmembrane helix insertion. A higher throughput methodology allows us to readily generate large ensembles and estimate apparent free energies of insertion of helices. Comparison of the simulation-based estimates of the apparent free energies of insertion with published data for translocon-mediated insertion of CFTR-derived helices reveals a good correlation with experimental data. This correlation is strongest if simulations use a mixed (DPPC/DPPG/DPPE) phospholipid bilayer and uncharged glutamate side chains in the peptides. Comparison of values of the apparent free energy of insertion from self-assembly simulations with those from CG-MD PMFs (for model peptides) and from translocon-mediated insertion studies (for CFTR-derived peptides) are suggestive of a nonequilibrium model of TM helix insertion into bilayers.

Having established that simulation results may be profitably compared with modestly large experimental datasets, it might be of some interest conduct a meta-study of different simulation, experimental, and bioinformatics approaches to prediction of TM helix insertion for a large and standardized test set of membrane protein sequences. This would be timely, because bioinformatics methods for membrane protein modeling (see, e.g., (62,63)) are now starting to take advantage of both the larger dataset of membrane proteins structures available and the use of CG-MD simulations to predict membrane protein/lipid interactions within a bilayer (37). Combining such a study with simulation studies which allow for the influence of unfolded/folded transitions on insertion energetics (23,64) could provide further insights into the likely mechanisms of TM helix insertion both in vitro and via the translocon machinery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aleksandra Watson and Kathryn Scott for useful comments.

We thank the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (through the Oxford Centre for Integrative Systems Biology) for funding this research.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Wallin E., von Heijne G. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terstappen G.C., Reggiani A. In silico research in drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001;22:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majd S., Yusko E.C., Mayer M. Applications of biological pores in nanomedicine, sensing, and nanoelectronics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010;21:439–476. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White S.H., von Heijne G. How translocons select transmembrane helices. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:23–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deber C.M., Goto N.K. Folding proteins into membranes. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:815–818. doi: 10.1038/nsb1096-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Killian J.A., Nyholm T.K.M. Peptides in lipid bilayers: the power of simple models. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Planque M.R.R., Kruijtzer J.A.W., Killian J.A. Different membrane anchoring positions of tryptophan and lysine in synthetic transmembrane α-helical peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:20839–20846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.20839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Killian J.A. Synthetic peptides as models for intrinsic membrane proteins. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdirekcan S., Rijkers D.T.S., Killian J.A. Influence of flanking residues on tilt and rotation angles of transmembrane peptides in lipid bilayers. A solid-state H-2 NMR study. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1004–1012. doi: 10.1021/bi0481242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vostrikov V.V., Hall B.A., Sansom M.S.P. Changes in transmembrane helix alignment by arginine residues revealed by solid-state NMR experiments and coarse-grained MD simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5803–5811. doi: 10.1021/ja100598e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Planque M.R.R., Killian J.A. Protein-lipid interactions studied with designed transmembrane peptides: role of hydrophobic matching and interfacial anchoring. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2003;20:271–284. doi: 10.1080/09687680310001605352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridder A.N., Morein S., Killian J.A. Analysis of the role of interfacial tryptophan residues in controlling the topology of membrane proteins. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6521–6528. doi: 10.1021/bi000073v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strandberg E., Killian J.A. Snorkeling of lysine side chains in transmembrane helices: how easy can it get? FEBS Lett. 2003;544:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hessa T., Kim H., von Heijne G. Recognition of transmembrane helices by the endoplasmic reticulum translocon. Nature. 2005;433:377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature03216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enquist K., Fransson M., Nilsson I. Membrane-integration characteristics of two ABC transporters, CFTR and P-glycoprotein. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;387:1153–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaud S., Fernández-Vidal M., White S.H. Insertion of short transmembrane helices by the Sec61 translocon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11588–11593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900638106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hessa T., White S.H., von Heijne G. Membrane insertion of a potassium-channel voltage sensor. Science. 2005;307:1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1109176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindahl E., Sansom M.S.P. Membrane proteins: molecular dynamics simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tieleman D.P., Forrest L.R., Berendsen H.J. Lipid properties and the orientation of aromatic residues in OmpF, influenza M2, and alamethicin systems: molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17554–17561. doi: 10.1021/bi981802y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacCallum J.L., Bennett W.F.D., Tieleman D.P. Distribution of amino acids in a lipid bilayer from computer simulations. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3393–3404. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.112805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson A.C.V., Lindahl E. Protein contents in biological membranes can explain abnormal solvation of charged and polar residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15684–15689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905394106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson A.C.V., Lindahl E. The role of lipid composition for insertion and stabilization of amino acids in membranes. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:185101. doi: 10.1063/1.3129863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulmschneider M.B., Smith J.C., Ulmschneider J.P. Peptide partitioning properties from direct insertion studies. Biophys. J. 2010;98:L60–L62. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shelley J.C., Shelley M.Y., Klein M.L. A coarse grain model for phospholipid simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:4464–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrink S.J., de Vries A.H., Mark A.E. Coarse grained model for semiquantitative lipid simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:750–760. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen S.O., Lopez C.F., Klein M.L. Coarse grain models and the computer simulation of soft materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2004;16:R481–R512. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voth G.A. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2008. Coarse-Graining of Condensed Phase and Biomolecular Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monticelli L., Kandasamy S.K., Marrink S.J. The MARTINI coarse grained force field: extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Periole X., Huber T., Sakmar T.P. G protein-coupled receptors self-assemble in dynamics simulations of model bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10126–10132. doi: 10.1021/ja0706246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treptow W., Marrink S.-J., Tarek M. Gating motions in voltage-gated potassium channels revealed by coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:3277–3282. doi: 10.1021/jp709675e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yefimov S., van der Giessen E., Marrink S.J. Mechanosensitive membrane channels in action. Biophys. J. 2008;94:2994–3002. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bond P.J., Sansom M.S.P. Insertion and assembly of membrane proteins via simulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2697–2704. doi: 10.1021/ja0569104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bond P.J., Holyoake J., Sansom M.S.P. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins and peptides. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;157:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bond P.J., Wee C.L., Sansom M.S.P. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations of the energetics of helix insertion into a lipid bilayer. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11321–11331. doi: 10.1021/bi800642m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Psachoulia E., Fowler P.W., Sansom M.S.P. Helix-helix interactions in membrane proteins: coarse-grained simulations of glycophorin α-helix dimerization. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10503–10512. doi: 10.1021/bi800678t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott K.A., Bond P.J., Sansom M.S.P. Coarse-grained MD simulations of membrane protein-bilayer self-assembly. Structure. 2008;16:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vorobyov I., Li L., Allen T.W. Assessing atomistic and coarse-grained force fields for protein-lipid interactions: the formidable challenge of an ionizable side chain in a membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9588–9602. doi: 10.1021/jp711492h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gkeka P., Sarkisov L. Interactions of phospholipid bilayers with several classes of amphiphilic α-helical peptides: insights from coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:826–839. doi: 10.1021/jp908320b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorairaj S., Allen T.W. On the thermodynamic stability of a charged arginine side chain in a transmembrane helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4943–4948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610470104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindahl E., Hess B., van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J. Mol. Model. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Berendsen H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Planque M.R., Bonev B.B., Killian J.A. Interfacial anchor properties of tryptophan residues in transmembrane peptides can dominate over hydrophobic matching effects in peptide-lipid interactions. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5341–5348. doi: 10.1021/bi027000r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung L.A., Lear J.D., DeGrado W.F. Fluorescence studies of the secondary structure and orientation of a model ion channel peptide in phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1992;31:6608–6616. doi: 10.1021/bi00143a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lear J.D., Wasserman Z.R., DeGrado W.F. Synthetic amphiphilic peptide models for protein ion channels. Science. 1988;240:1177–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.2453923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Åkerfeldt K.S., Lear J.D., DeGrado W.F. Synthetic peptides as models for ion channel proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozdirekcan S., Etchebest C., Fuchs P.F. On the orientation of a designed transmembrane peptide: toward the right tilt angle? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15174–15181. doi: 10.1021/ja073784q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chetwynd A., Wee C.L., Sansom M.S.P. The energetics of transmembrane helix insertion into a lipid bilayer. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2534–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacCallum J.L., Bennett W.F.D., Tieleman D.P. Partitioning of amino acid side chains into lipid bilayers: results from computer simulations and comparison to experiment. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:371–377. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharpe H.J., Stevens T.J., Munro S. A comprehensive comparison of transmembrane domains reveals organelle-specific properties. Cell. 2010;142:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishnakumar S.S., London E. Effect of sequence hydrophobicity and bilayer width upon the minimum length required for the formation of transmembrane helices in membranes. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;374:671–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yano Y., Ogura M., Matsuzaki K. Measurement of thermodynamic parameters for hydrophobic mismatch 2: intermembrane transfer of a transmembrane helix. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3379–3385. doi: 10.1021/bi052286w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bretscher M.S., Munro S. Cholesterol and the Golgi apparatus. Science. 1993;261:1280–1281. doi: 10.1126/science.8362242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Munro S. Localization of proteins to the Golgi apparatus. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shahidullah K., London E. Effect of lipid composition on the topography of membrane-associated hydrophobic helices: stabilization of transmembrane topography by anionic lipids. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:704–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Call M.E., Schnell J.R., Wucherpfennig K.W. The structure of the ζζ transmembrane dimer reveals features essential for its assembly with the T cell receptor. Cell. 2006;127:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cuthbertson J.M., Doyle D.A., Sansom M.S.P. Transmembrane helix prediction: a comparative evaluation and analysis. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2005;18:295–308. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzi032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee H., Larson R.G. Lipid bilayer curvature and pore formation induced by charged linear polymers and dendrimers: the effect of molecular shape. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:12279–12285. doi: 10.1021/jp805026m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee H., Larson R.G. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics studies of the concentration and size dependence of fifth- and seventh-generation PAMAM dendrimers on pore formation in DMPC bilayer. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:7778–7784. doi: 10.1021/jp802606y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kelm S., Shi J., Deane C.M. iMembrane: homology-based membrane-insertion of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1086–1088. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nugent T., Jones D.T. Predicting transmembrane helix packing arrangements using residue contacts and a force-directed algorithm. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nymeyer H., Woolf T.B., Garcia A.E. Folding is not required for bilayer insertion: replica exchange simulations of an α-helical peptide with an explicit lipid bilayer. Proteins. 2005;59:783–790. doi: 10.1002/prot.20460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.