Abstract

Background

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) occurs in a fraction of patients with multiple sclerosis who were treated with natalizumab. Most adults who are infected with the JC virus, the etiologic agent in PML, do not have symptoms. We sought to determine whether exposure to natalizumab causes subclinical reactivation and neurotropic transformation of JC virus.

Methods

We followed 19 consecutive patients with multiple sclerosis who were treated with natalizumab over an 18-month period, performing quantitative polymerase-chain-reaction assays in blood and urine for JC virus reactivation; BK virus, a JC virus–related polyomavirus, was used as a control. We determined JC virus–specific T-cell responses by means of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay and antibody responses by means of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and analyzed JC virus regulatory-region sequences.

Results

After 12 months of natalizumab therapy, the prevalence of JC virus in the urine of the 19 patients increased from a baseline value of 19% to 63% (P = 0.02). After 18 months of treatment, JC virus was detectable in 3 of 15 available plasma samples (20%) and in 9 of 15 available samples of peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (60%) (P = 0.02). JC virus regulatory-region sequences in blood samples and in most of the urine samples were similar to those usually found in PML. Conversely, BK virus remained stable in urine and was undetectable in blood. The JC virus–specific cellular immune response dropped significantly between 6 and 12 months of treatment, and variations in the cellular immune response over time tended to be greater in patients in whom JC viremia developed. None of the patients had clinical or radiologic signs of PML.

Conclusions

Subclinical reactivation of JC virus occurs frequently in natalizumab-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Viral shedding is associated with a transient drop in the JC virus–specific cellular immune response.

As of july 24, 2009, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a deadly demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, had been reported in 13 patients with multiple sclerosis: 2 who were treated with a combination of natalizumab (Tysabri, Elan Pharmaceuticals and Biogen Idec) and interferon beta-1a (Avonex)1-3 and 11 who received natalizumab monotherapy.4-7 One additional patient with Crohn's disease who was treated with natalizumab died from PML.8 PML is caused by the reactivation of JC virus and affects patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or leukemia and recipients of organ transplants, but it had never been reported in a person with multiple sclerosis before natalizumab treatment was introduced. Natalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against α4β1 and α4β7 integrin receptors, prevents normal extravasation of leukocytes out of the bloodstream.9 The mechanism underlying JC virus reactivation in multiple sclerosis is unknown. JC virus remains latent in the kidney and lymphoid organs and can be found in the urine in one third of both healthy and immunosuppressed adults with or without PML.10-12 JC virus is usually not found in the blood of healthy persons or of untreated patients with multiple sclerosis,13,14 but it can be detected in the blood of 20 to 40% of patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)13,15 and in 60 to 80% of those with PML.13,16 In this last group, the JC virus regulatory region contains signature rearrangements, including duplications, deletions, and mutations, which are also consistently found in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with PML but not in their urine.17,18

Natalizumab also triggers the release of immature leukocytes from the bone marrow. It has been hypothesized that these cells may be infected with JC virus19 and, in some patients, may carry the virus into the brain, leading to PML.

Natalizumab does not affect antibody production. Most adults are seropositive for JC virus, and although the humoral immune response cannot prevent a reactivation of JC virus and the development of PML, we and others have found that the cellular immune response plays a crucial role in the containment of JC virus20-24 and is mediated by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. The BK virus, a polyomavirus related to JC virus, may be reactivated in patients with multiple sclerosis who are treated with natalizumab.25 BK virus is the etiologic agent in the nephropathy noted in recipients of kidney transplants.

In this study, we sought to determine whether JC virus reactivation and neurotropic transformation occur in the blood, urine, or both of patients with multiple sclerosis who were treated with natalizumab over an 18-month period. We used BK virus as a control virus and correlated virologic measurements with the cellular immune responses against JC virus.

Methods

Selection of Study Subjects

Nineteen consecutive patients who had received a diagnosis of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis at the Multiple Sclerosis Clinic of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Neurology Department provided written informed consent to be enrolled in this study before they started taking natalizumab in 2006. The patient group consisted of 15 women and 4 men, with a median age of 42 years (range, 21 to 51). The median duration of the disease since the time of diagnosis was 5 years (range, 8 months to 19 years). Fourteen patients had been receiving interferon beta and one had been receiving glatiramer acetate until a minimum of 4 weeks (range, 4 weeks to 2 years) before the start of natalizumab therapy as a monthly infusion. None of the patients had been treated with corticosteroids for a median period of 13 weeks (range, 4 weeks to 2 years) before taking natalizumab. Blood and urine samples were collected before the patients started treatment with natalizumab and then at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, at the time of their natalizumab infusion.

Detection of Viral DNA by Quantitative PCR Assay

Quantitative real-time polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) was used to measure BK virus DNA26 and JC virus DNA27 in urine, plasma, and peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), as described previously.26-28 The lower limit of detection for either virus was 10 copies per microgram of cellular DNA in PBMC samples and 25 copies per milliliter in plasma or urine samples.

PCR Amplification, Cloning, and Sequencing of the JC Virus Regulatory Region

The regulatory region of JC virus was subjected to PCR amplification, as described in the literature.29 The PCR products were then cloned with use of a plasmid cloning kit (pCR 2.1-TOPO vector [Invitrogen]) and subjected to sequencing on an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Assays

To detect T cells specific for the JC virus protein VP1, we performed an interferon gamma immunospot assay30 (ELISpot Assay, R&D Systems), using cultured PBMCs from the patients, as described in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed to detect IgG and IgM antibodies against the JC and BK viruses in the patients' blood samples, as described previously.31,32

Statistical Analysis

The prevalence of JC virus and BK virus detected in urine, plasma, and PBMCs at each time point (3, 6, 12, and 18 months) was compared with the use of a two-sided Fisher's exact test. For the analysis of the cellular immune response against JC virus, assessed with the enzyme-linked immunospot assay, we used the nonparametric median test to compare the median level of immune response across time points within each pool. In addition, we combined all data across the four pools and used random-coefficient models to test for the rate of change in the immune response over time. We analyzed changes at the patient level from baseline to 12 months to estimate the rates of JC virus acquisition and loss in urine. The changes in these rates were tested by means of McNemar's test. All reported P values are two-sided. We used SAS/STAT software33 for all statistical analyses.

Results

Clinical Outcomes

During the 18-month period of observation, none of the patients had a neurologic deficit or new brain lesions consistent with PML. Four patients who presented with relapses of multiple sclerosis (Patients 3, 8, 16, and 19) were treated intermittently with corticosteroids. A total of 19 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies were performed during the study period in 11 patients (Patients 3 through 8, 12, 15 through 17, and 19). These studies were performed routinely at 1 year in six patients and in five patients when new neurologic symptoms arose that differed from these patients' usual flares of multiple sclerosis. None of the MRI scans showed new lesions suggestive of PML. Natalizumab was withdrawn after 12 months in Patients 1, 14, 16, and 17 to establish a drug holiday, following a report of new natalizumab-associated cases of PML,5 and these four patients were not studied further at 18 months.

Detection of Viral DNA in Urine

The frequency of BK virus–positive urine samples remained low, oscillating between 5 and 21% of patients (Table 1), and only one patient had more than one positive sample. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of BK virus in urine over time (P = 0.68).

Table 1. Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Who Had Detectable Viral Loads during 18 Months of Treatment with Natalizumab.

| Time of Testing | BK Virus in Urine* | JC Virus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Plasma | PBMCs | ||

| no. positive/no. tested | ||||

| Before treatment | 2/16 | 3/16 | 0/19 | 0/19 |

|

| ||||

| At 3 mo | 4/19 | 4/19 | 0/19 | 0/19 |

|

| ||||

| At 6 mo | 2/19 | 5/19 | 0/19 | 0/19 |

|

| ||||

| At 12 mo | 1/19 | 12/19 | 1/19 | 1/19 |

|

| ||||

| At 18 mo | 1/14 | 6/14 | 3/15 | 9/15 |

BK virus was not detected in samples of plasma or peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

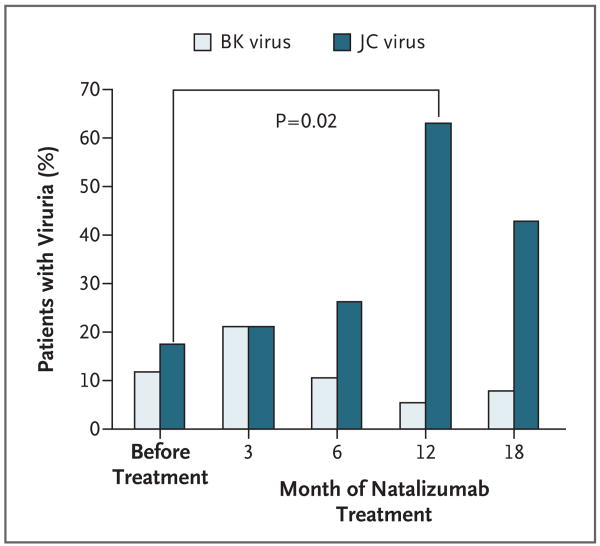

In contrast, the frequency of JC virus–positive urine samples markedly increased, from 19% at baseline to 63% after 12 months of therapy (P = 0.02) (Fig. 1), and eight patients had multiple positive samples. There was a significant difference in the prevalence of JC virus in urine over time (P = 0.03); it was undetectable in 13 of 16 patients (81%) at baseline but became detectable (indicating JC virus acquisition) in 9 of 16 patients (56%) at 12 months. Conversely, JC virus was detectable at baseline in 3 of 16 patients (19%) but became undetectable (indicating JC virus loss) at 12 months in 2 of 16 patients (12%) (P = 0.04).

Figure 1. Frequency of JC Virus and BK Virus DNA in Urine from Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Treated with Natalizumab.

The graphs show the percentage of patients with detectable viral DNA, as measured on PCR assay, before natalizumab treatment and 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after treatment was started. The difference between the number of subjects with JC viruria before and the number 12 months after the start of natalizumab therapy was significant (P = 0.02, with a two-sided Fisher's exact test).

However, viral loads for both the BK and JC viruses remained relatively low, within a range of 1 to 3 log10 copies among positive urine samples, except in Patient 15, who had a viral load for JC virus that ranged from 3 to 6 log10 copies.

Detection of Viral DNA in Plasma and Peripheral-Blood Mononuclear Cells

BK virus DNA was not detectable in any of the available specimens. At 12 months, JC virus DNA was detectable in 1 of 19 plasma samples (5%) and in 1 of 19 samples of PBMCs (5%). At 18 months, JC virus DNA was present in 3 of 15 available plasma samples (20%) and in 9 of 15 available PBMC samples (60%) — a difference that was significant (P = 0.02). All subjects who had positive plasma samples also had JC virus DNA in their PBMCs at the same time point. There was a significant difference in the prevalence of JC virus over time in the plasma samples (P = 0.02) and in the PBMC samples (P<0.001). Specifically, the difference between JC virus detection in PBMCs before treatment and at 18 months was significant (P<0.001). However, the viral load for JC virus remained low among positive samples, between 125 and 683 copies per milliliter of plasma and between 28 and 880 copies per microgram of PBMC DNA. All but one of nine patients with detectable JC virus in PBMCs at 18 months also had JC virus in urine 6 months earlier. Therefore, the sensitivity of the finding of JC virus in urine during the first year of treatment as an indicator of subsequent detection of JC virus in PBMCs at 18 months was 89% (8 of 9 subjects), with a positive predictive value of 62% (8 of 13 subjects).

Sequencing the JC Virus Regulatory Region

To determine whether the molecular characteristics of JC virus strains found in patients with multiple sclerosis who were treated with natalizumab were associated with neurotropism, we used PCR amplification and cloning and sequenced the JC virus regulatory region from the PBMCs of three patients (Patients 8, 12, and 19) and from the plasma of one patient (Patient 13) in whom viremia developed at 18 months. Sequence analysis of one to seven clones from each patient showed a regulatory region with a tandem repeat pattern consistent with JC virus central nervous system isolate MAD-1, but each contained different point mutations. In addition, two of five clones from a plasma sample from Patient 13 showed a single 98-bp unit devoid of inserts usually seen in the archetypal regulatory region. Conversely, the sequence of the JC virus regulatory region analyzed from the urine of one patient who had a consistently high level of viruria throughout the study (Patient 15) revealed an archetypal regulatory region with various point mutations in six of six clones. However, sequence analysis of one to five clones from each of the urine samples from eight patients with viruria during natalizumab therapy (Patients 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, and 14) showed a regulatory region with a tandem repeat pattern consistent with the central nervous system isolate MAD-1, although with various point mutations.

Detection of the Cellular Immune Response against JC Virus

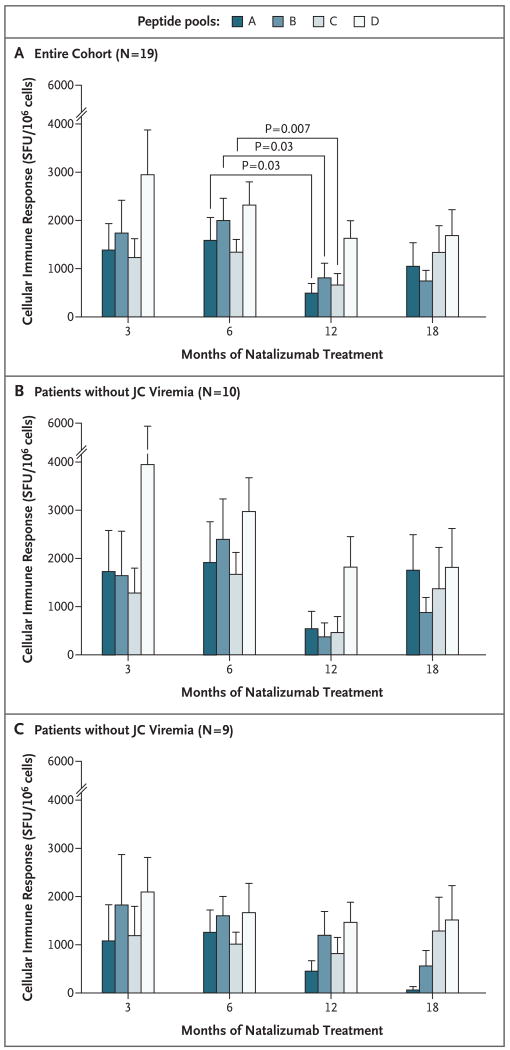

To assess whether variations in the viral load of JC virus during natalizumab therapy were associated with changes in the immune response against this virus, we isolated PBMCs from fresh blood samples by centrifugation on a Ficoll gradient and then sought to detect JC virus–specific T cells by means of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay, using four pools of overlapping peptides (A, B, C, and D) to cover the entire JC virus protein VP1 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Cellular Immune Responses against JC Virus in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Treated with Natalizumab.

The cellular immune responses, represented by the number of spot-forming units (SFU) per 106 cells, indicating the production of interferon gamma, were measured over time after stimulation of PBMCs with four pools of overlapping peptides (A through D) covering the entire JC virus VP1 protein. Values are means +SD. Panel A shows the responses for the entire cohort (19 patients), with significant differences between 6 and 12 months of treatment for pools A, B, and C. Panel B shows the responses in the 10 subjects with detectable viremia. Panel C shows the responses in the nine subjects with undetectable JC viremia.

First, we tested variations in the immune response against each peptide pool during natalizumab therapy in our entire cohort. Pools A and C showed significant differences in the medians over time (P = 0.03 and P = 0.05, respectively), whereas these differences were not significant for pools B and D. There was a significant drop in the median number of spot-forming units (SFU) between 6 and 12 months for pools A (P = 0.03), B (P = 0.03), and C (P = 0.007), whereas the change was not significant for pool D.

We then explored whether the appearance of JC virus DNA in PBMCs was associated with variations in the cellular immune response. To accomplish this we divided our cohort into two groups according to whether JC virus DNA was detected in PBMCs (Fig. 2B and 2C), and we looked at the global immune response against VP1, as measured by the sum of the assay results for all four peptide pools. On repeated-measures data analysis, we noted a decrease in the immune response over time among the 10 patients in whom viremia developed (mean [±SE] value, −330±191 SFU per month, P = 0.11), whereas in the 9 patients without viremia, the immune response was less diminished during natalizumab therapy (−151±181 SFU per month, P = 0.42).

Detection of the Humoral Immune Response against JC and BK Viruses

On enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, all 19 patients had antibodies against JC virus and 18 of the 19 had antibodies against BK virus. However, the anti–JC virus antibody response was not sustained at all time points in 10 of the patients, and 6 of the 19 (32%) had anti–JC virus IgM antibodies but no anti–JC virus IgG antibodies. There was no significant difference in serologic results between patients with JC virus in blood samples and those without it.

Discussion

This pilot study showed an increase in the frequency of JC virus excretion in urine, which was noted in 63% of the 19 patients with multiple sclerosis after 12 months of natalizumab therapy, with viremia detected at 18 months in 60% of the patients tested. This finding contrasts with the consistent observation of JC virus in urine in only one third of people in cross-sectional studies10-13 and the observation that the frequency of JC viruria is not increased in the setting of immunosuppression or even PML.13 Furthermore, less than 5% of immunocompetent persons and patients with multiple sclerosis who are not treated with natalizumab have detectable JC virus DNA in their blood.13,14 Therefore, the frequency of JC viremia reached in our patients with multiple sclerosis who were treated with natalizumab was higher than that observed in patients infected with HIV and similar only to that seen in patients with PML.13 JC virus DNA was detected more frequently in PBMC samples than in plasma samples. Others who investigated plasma samples of patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab exclusively did not detect an increase in JC virus.28 The differences between the findings in PBMCs and those in plasma suggest that JC virus reactivation and dissemination in patients receiving natalizumab therapy is cell-associated rather than cell-free.

It has been hypothesized that immature leukocytes infected by JC virus34 are released from bone marrow stores early after the onset of treatment with natalizumab.19 JC virus is present in 13% of bone marrow samples from HIV-negative patients who have hematologic conditions.35 However, it is not known whether JC virus is also present in the bone marrow of patients with multiple sclerosis. In addition, viral shedding occurred much later in our cohort than one would have expected from the early effect of natalizumab on the release of bone marrow cells.9 Furthermore, viremia followed the increase in viruria. Therefore, the initial site of JC virus reactivation may have been the kidney, owing perhaps to decreased immunosurveillance in this compartment caused by natalizumab, which led to a secondary spread of virus to hematopoietic sites and the subsequent release of JC virus–infected cells into the bloodstream.

Most sequences in the JC virus regulatory region in the PBMC and plasma samples from these patients were composed of tandem repeats similar to those in strains usually found in the blood and central nervous system of patients with PML,17 but each contained unique point mutations, ruling out contamination among samples or with plasmid DNA. These findings suggest that the JC virus strains in the blood of our patients were indeed neurotropic and neurovirulent. Conversely, the regulatory region of JC virus found in urine had the expected stable and nonpathogenic archetypal pattern seen in the one patient who had persistently high levels of JC virus in urine throughout the study. However, the neurotropic form of the JC virus regulatory region was detected for the first time in the urine of eight patients in whom viruria developed during natalizumab therapy. Thus, JC virus may reactivate and undergo neurotropic transformation in the kidneys of natalizumab-treated patients. Our findings suggest that monitoring for JC virus in the urine of patients receiving natalizumab therapy and also, after 18 months, in PBMCs in patients with viruria could provide some insight into viral replication. The mechanisms involved appear to be quite specific for JC virus, since we found in our study that BK virus, which also resides in the kidney and shares epitopes with JC virus that are recognized by the same population of cytotoxic T cells,26,36 showed no sign of reactivation either in blood or in urine.

Since natalizumab decreases the extravasation of leukocytes outside the bloodstream but is not known to affect immune cells directly, the drop in the T-cell response against the JC virus protein VP1 between the 6- and 12-month time points was a surprise. These results suggest that natalizumab may in fact directly alter the capacity of T cells to react against JC virus. The fact that the drop in the immune response was concomitant with an increased incidence of JC viruria supports this possibility. Furthermore, the decrease in the cellular immune response was more pronounced in patients with JC virus reactivation in their blood than in those without. Therefore, it is possible that natalizumab has a direct negative effect on JC virus–specific T cells, occurring at around 1 year of treatment, which may have participated in JC virus reactivation in the kidney and its subsequent spread into the blood.

This pilot study has several limitations. First, the number of patients enrolled was small. Second, we did not collect cerebrospinal fluid samples and therefore could not determine whether subclinical reactivation of JC virus also occurred in the central nervous system, as has been claimed by others.25 Third, we did not measure the cellular immune response in our patients before they began treatment with natalizumab. However, in a previous study using the chromium-51 release assay, we found that untreated patients with multiple sclerosis have a vigorous cellular immune response against JC virus mediated by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.14 For the present study, we used a different peptide library, which allowed us to encompass all possible 9aa epitopes of the JC virus VP1 protein presented on major-histocompatibility-complex (MHC) class I molecules to CD8+ T cells and all possible 12aa epitopes presented on MHC class II molecules to CD4+ T cells. Therefore, we believe that our assessment of the cellular immune response during the course of natalizumab therapy was robust and comprehensive.

Taken together, our findings shed new light on possible mechanisms that lead to JC virus reactivation in patients with multiple sclerosis who are treated with natalizumab. However, we do not suggest any change in the management of multiple sclerosis, since the clinical implications of this pilot study are still not known. Nevertheless, our results also pose more questions and open new avenues for research. First, whether measurement of the viral load in blood and urine is an adequate surrogate marker of the activity of the virus in the central nervous system remains to be determined. Second, if indeed natalizumab triggers the appearance of JC virus–infected PBMCs in the bloodstream, how can these cells disseminate the virus to the central nervous system, since their extravasation into the brain parenchyma is selectively blocked by the medication? As the number of patients with multiple sclerosis in whom PML develops during natalizumab therapy continues to increase, these questions will require urgent answers. Molecular monitoring of JC virus may allow early identification of patients at risk for PML in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS 041198 and R01 NS 047029, and K24 NS 060950 [to Dr. Koralnik]).

Dr. Koralnik reports receiving lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Merck Serono, Antisense Pharma, and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and grant support from Biogen Idec; Dr. Kinkel, receiving consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis, lecture fees from Biogen Idec, and grant support from Biogen Idec and Genzyme; and Dr. Miller, owning equity in Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

We thank Kevin Carlson, David Quinn, and Harikrishnan Balachandran for technical assistance.

Footnotes

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:375–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger JR, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and natalizumab — unforeseen consequences. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:414–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:369–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox M. MS drug Tysabri may promote brain infection: study. [August 14, 2009];2008 December; at http://www.reuters.com/article/healthNews/idUSTRE4BF5GF20081216.

- 5.FDA MedWatch. Tysabri (natalizumab) — two new cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in European patients receiving drug as monotherapy for multiple sclerosis for more than one year. [August 14, 2009];2008 at http://www.pharmacistelink.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=10348&Itemid=311.

- 6.Jeffrey S. New case of PML with natalizumab monotherapy. New York: Medscape Rheumatology; Dec, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tysabri update. [August 14, 2009]; at http://investor.biogenidec.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=148682&p=irol-TPME.

- 8.Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:362–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ransohoff RM. Natalizumab for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2622–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct071462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur RR, Dagostin S, Shah KV. Detection of BK virus and JC virus in urine and brain tissue by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1174–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1174-1179.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura T, Aso Y, Kuniyoshi N, Hara K, Yogo Y. High incidence of urinary JC virus excretion in nonimmunosuppressed older patients. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1128–33. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markowitz RB, Thompson HC, Mueller JF, Cohen JA, Dynan WS. Incidence of BK virus and JC virus viruria in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and -uninfected subjects. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:13–20. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, Lord CI, Letvin NL. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52:253–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Pasquier RA, Stein MC, Lima MA, et al. JC virus induces a vigorous CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;176:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubois V, Dutronc H, Lafon ME, et al. Latency and reactivation of JC virus in peripheral blood of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2288–92. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2288-2292.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tornatore C, Berger JR, Houff SA, et al. Detection of JC virus DNA in peripheral lymphocytes from patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:454–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfister LA, Letvin NL, Koralnik IJ. JC virus regulatory region tandem repeats in plasma and central nervous system isolates correlate with poor clinical outcome in patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Virol. 2001;75:5672–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5672-5676.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen PN, Major EO. A classification scheme for human polyomavirus JCV variants based on the nucleotide sequence of the noncoding regulatory region. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:280–7. doi: 10.1080/13550280152537102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ransohoff RM. Natalizumab and PML. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1275. doi: 10.1038/nn1005-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du Pasquier RA, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, et al. Low frequency of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against the novel HLA-A*0201-restricted JC virus epitope VP1(p36) in patients with proven or possible progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Virol. 2003;77:11918–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.11918-11926.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasnault J, Kahraman M, de Goër de Herve MG, Durali D, Delfraissy JF, Taoufik Y. Critical role of JC virus-specific CD4 T-cell responses in preventing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. AIDS. 2003;17:1443–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Pasquier RA, Kuroda MJ, Zheng Y, Jean-Jacques J, Letvin NL, Koralnik IJ. A prospective study demonstrates an association between JC virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and the early control of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Brain. 2004;127:1970–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koralnik IJ, Du Pasquier RA, Kuroda MJ, et al. Association of prolonged survival in HLA-A2+ progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy patients with a CTL response specific for a commonly recognized JC virus epitope. J Immunol. 2002;168:499–504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima MA, Marzocchetti A, Autissier P, et al. Frequency and phenotype of JC virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Virol. 2007;81:3361–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01809-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puccio L, Dinzey J, Poopatana CA, Barrett KV, Sadiq SA. Detection of JC/BK virus in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. Program and abstracts of the 60 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; Chicago. April 12-19, 2008; abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Trofe J, Gordon J, et al. Interplay of cellular and humoral immune responses against BK virus in kidney transplant recipients with polyomavirus nephropathy. J Virol. 2006;80:3495–505. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3495-3505.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryschkewitsch C, Jensen P, Hou J, Fahle G, Fischer S, Major EO. Comparison of PCR-Southern hybridization and quantitative real-time PCR for the detection of JC and BK viral nucleotide sequences in urine and cerebrospinal fluid. J Virol Methods. 2004;121:217–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yousry TA, Major EO, Ryschkewitsch C, et al. Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:924–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monaco MC, Jensen PN, Hou J, Durham LC, Major EO. Detection of JC virus DNA in human tonsil tissue: evidence for site of initial viral infection. J Virol. 1998;72:9918–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9918-9923.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Letvin NL, Rao SS, Dang V, et al. No evidence for consistent virus-specific immunity in simian immunodeficiency virus-exposed, uninfected rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2007;81:12368–74. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00822-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viscidi RP, Rollison DE, Viscidi E, et al. Serological cross-reactivities between antibodies to simian virus 40, BK virus, and JC virus assessed by virus-like-particle-based enzyme immunoassays. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:278–85. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.2.278-285.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rollison DE, Engels EA, Halsey NA, Shah KV, Viscidi RP, Helzlsouer KJ. Prediagnostic circulating antibodies to JC and BK human polyomaviruses and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:543–50. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SAS/STAT software, version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monaco MC, Atwood WJ, Gravell M, Tornatore CS, Major EO. JC virus infection of hematopoietic progenitor cells, primary B lymphocytes, and tonsillar stromal cells: implications for viral latency. J Virol. 1996;70:7004–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7004-7012.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan CS, Dezube BJ, Bhargava P, et al. Detection of JC virus DNA and proteins in bone marrow of HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients: implications for viral latency and neurotropic transformation. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:881–8. doi: 10.1086/597117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krymskaya L, Sharma MC, Martinez J, et al. Cross-reactivity of T lymphocytes recognizing a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope within BK and JC virus VP1 polypeptides. J Virol. 2005;79:11170–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11170-11178.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.