Abstract

Background

The goal of this project was to identify key effective components of ADVANCE, a family-centred preoperative intervention programme, through the use of a dismantling approach. ADVANCE was previously demonstrated to be more effective than parental presence and just as effective as midazolam in reducing children's preoperative anxiety. The total programme, however, may be difficult to implement in hospitals across the country.

Methods

Subjects in this follow-up dismantling report were 96 children aged 2–10 who were part of the original study and who underwent anaesthesia and surgery. Baseline characteristics, parental adherence to the components of ADVANCE, and child and parent anxiety were assessed.

Results

We found that greater parental adherence to the ADVANCE intervention was associated with lower child anxiety before surgery. The two components of ADVANCE that emerged as having a significant impact on children's anxiety were practising with the anaesthesia mask at home and parental planning and use of distraction in the preoperative holding area. In fact, not only did children experience significantly less preoperative anxiety when their parents were adherent to mask practise and use of distraction, their anxiety tended to remain stable and relatively low throughout the preoperative period.

Conclusions

Shaping and exposure (i.e. practise with the anaesthesia mask) and parental use of distraction in the surgical setting are two beneficial components that could be included in preoperative preparation programmes that will be designed in the future.

Keywords: children; surgery, paediatric; surgery, preoperative period

Editor's key points.

A family-centred preoperative programme was previously found to reduce anxiety in children.

In this study, individual components of the programme were evaluated.

Prior exposure to the anaesthesia mask and parental use of distraction were critical in reducing anxiety.

The study provides important information on how to involve parents constructively when their children undergo surgery.

Millions of children undergo surgery each year and the majority of these children develop significant anxiety before surgery.1–3 Preoperative anxiety is associated with adverse clinical, behavioural, and psychological outcomes, including delayed recovery, increased postoperative pain and analgesic requirements, and new onset negative behavioural changes after surgery.3–5 Various effective interventions targeting preoperative anxiety in children exist. Our group developed a family-centred, behavioural preparation programme and demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial that this intervention (ADVANCE) was more effective than standard of care and parental presence at induction of anaesthesia and just as effective as the commonly used sedative midazolam in reducing children's preoperative anxiety.6

ADVANCE is based on behavioural principles of shaping, exposure, distraction, and modelling with coaching techniques and involves information provided through video, written pamphlets, and coaching of parents (see Kain and colleagues6 for a description of the intervention). Not only was ADVANCE shown to be effective in reducing children's preoperative anxiety, but was also shown to reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium, decrease time to discharge, and decrease the need for postoperative analgesics.6

Because ADVANCE contains multiple components such as video, exposure through home practise with the anaesthesia mask, and the use of distraction on the day of surgery, the total programme may be difficult to implement in hospitals in general. We sought to identify key components of this intervention through the use of a dismantling approach. That is, we examined each of the specific components of the intervention separately through statistical analysis in families that received ADVANCE before surgery to determine the components of ADVANCE that were most strongly related to decreased preoperative anxiety in children. We used the construct of adherence to the intervention by families to determine the relationship between the ADVANCE components and children's preoperative distress. We hypothesized that greater parental adherence to the intervention as a whole would result in significantly lower preoperative anxiety scores in children. In addition, based on prior research specifically focused on parental use of distraction to reduce children's anxiety and distress in the medical setting7–9 and our randomized controlled trial illustrating that exposure and shaping with the anaesthesia mask before surgery reduces children's anxiety at anaesthesia induction,10 we anticipated that parental adherence to mask practise before surgery and use of distraction on the day of surgery would be associated with lower levels of children's preoperative anxiety.

Methods

Participants in this report were part of a larger randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of the ADVANCE intervention compared with the standard of care, parental presence at induction of anaesthesia, and oral midazolam.6 Subjects included parents and children (aged 2–10 yr) who were ASA I or II and undergoing outpatient, elective surgery. To standardize the study sample, exclusion criteria included: prematurity (born before 36 weeks) or diagnosed developmental delay. Families were recruited between 2 and 7 days before the child's scheduled surgery during the standard preoperative visit, which included a 20 min programme involving an orientation tour of the operating theatres (OTs) and interviews with a nurse, anaesthesiologist, and child-life specialist. The Institutional Review Board approved the study and all parents provided written informed consent and children aged 7 and older provided written assent. In this current dismantling report, we include data only from subjects who were randomly assigned to the ADVANCE group in the original study (n=96). Results presented in the current paper have not previously been reported.

Measures

Baseline characteristics

Child temperament: This construct was assessed by parent-report using the EASI Temperament Survey. The EASI includes 20 items in four behavioural categories: Emotionality, Activity, Sociability, and Impulsivity.11,12 Reliability and validity of the EASI is acceptable.11,12

Parental anxiety: Parents completed ratings of their own state (situational) and trait (baseline) anxiety using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).13 The STAI is a widely used measure of anxiety and is well validated and has good reliability.13

Predictor variables: adherence to the components of ADVANCE

Adherence to the components of the ADVANCE intervention was assessed throughout the study6 by trained research assistants using the scale described below:

Video I: whether mother, father, and/or other caregiver watched the ADVANCE video (1, yes; 0, no);

Video II: how many times each individual watched the video (range 0–5);

Pamphlet: whether mother, father, and/or other caregiver read the ADVANCE pamphlet (1, yes; 0, no);

Mask practise: whether practise with the anaesthesia mask was completed with the child at home (2, yes; 1, partial practise; 0, no practise; for the purposes of the dismantling analyses, only scores of 2 were considered adherent, 0 and 1 were coded as non-adherent);

Use of distraction in holding area: whether parent(s) used the two previously identified distraction techniques on the day of surgery in the preoperative holding area (2, both planned distractions used; 1, only one of the two planned distractions were used; 0, no distraction was used; for the purposes of the dismantling analyses, only scores of 2 were considered adherent, 0 and 1 were coded as non-adherent);

Use of distraction in the OT: whether parents used the identified distraction techniques on the day of surgery in the OT (2, both planned distractions used; 1, only one of the two planned distractions were used; 0, no distraction was used; for the purposes of the dismantling analyses, only scores of 2 were considered adherent, 0 and 1 were coded as non-adherent).

Total adherence score: This was calculated by summing each of the individual adherence values for each family member. The potential score range is from 0 to 18.

Outcome variables: children's preoperative anxiety

The primary outcome variable used to examine the efficacy of the various ADVANCE components was children's preoperative anxiety, assessed using the modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale (mYPAS), a well-validated observational measure of children's distress using five behavioural categories (activity, emotional expressivity, state of arousal, vocalization, and use of parents).14–16 The mYPAS has been demonstrated to have good to excellent reliability and validity for assessment of children's anxiety in the preoperative holding area and at induction of anaesthesia.15,16 Here, the mYPAS was administered by trained research assistants (who established reliability levels of at least κ=0.80) at four time points: in the preoperative holding area, on the walk to the OT, at entrance to the OT, and introduction of the anaesthesia mask to the child.

Study protocol

Children and families received the ADVANCE intervention instruction and preparation materials, which consisted of a video, three pamphlets, and a mask practise kit on the day of their preoperative visit to the hospital. Parents were instructed to watch the video and read the pamphlets at least twice before the child's surgery. On days 1 and 2 immediately before the child's scheduled surgery, parents received telephone coaching by the researcher to assess parental adherence to the ADVANCE protocol and address any questions. On the day before surgery, the researcher also assessed the parents’ specific plans for distraction on the day of surgery during the telephone coaching call.

On the day of surgery, patient characteristic data were collected upon arrival to the hospital. As needed, parents were prompted to use planned distraction strategies in both the holding and OT areas. Children were also provided with a bag of distracting toys to play with during the preoperative period. See a full description of the ADVANCE intervention and protocol in the previously published manuscript.6 A standardized anaesthesia protocol was followed, which included introduction of anaesthesia using oxygen/nitrous oxide and sevoflurane administered through a scented mask. Parents were asked to leave the OT once the child exhibited loss of lid reflex.

Statistical analysis

The specific hypotheses and related statistical analyses were as follows: (i) Pearson product moment correlations were conducted to determine whether overall adherence (sum of all adherence items) was significantly associated with lower anxiety (mYPAS) at the four assessment points; (ii) Pearson product moment correlations were conducted between total adherence scores and patient characteristic variables (mother/father age, child age, child gender, parental education, and parental anxiety) to determine which factors may have related to increased adherence to each of the components of the intervention; (iii) children were grouped by high (upper 25%) and low (lower 25%) parental adherence and one-way analysis of variance (anova) was conducted to determine whether high adherence led to significant decreases in child anxiety (mYPAS); (iv) each individual adherence component was used as a grouping variable at the four assessment points during the preoperative procedure in a one-way anova to determine which components of the intervention had significant impacts on child anxiety (mYPAS); and (v) those components that were shown to be related to child preoperative anxiety were entered into a repeated-measures anova to examine the pattern of anxiety across phases of the preoperative procedure for those who were adherent vs non-adherent to those components. Statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Results

Overall adherence and children's preoperative anxiety

Patient characteristic and baseline data are presented in Table 1. Overall parental adherence was higher for parents of female children (r=0.23, P=0.03) and parents with higher education (r=0.24, P=0.02). No significant relationships emerged between adherence and age, child temperament, or parental anxiety. Overall adherence scores ranged from 0 to 17 [9.8 (3.0)]. Parental adherence to ADVANCE was significantly and negatively associated with child anxiety at introduction of the anaesthesia mask (r=−0.29, P<0.01), which has been shown to be the highest stress point in the preoperative period for children. To further validate the relationship of adherence to ADVANCE and anxiety, ANOVA indicated that children in the high parental adherence group had significantly lower mYPAS scores at mask introduction compared with children in the low adherence group [37.5 (17.8) vs 52.8 (25.7), P=0.01].

Table 1.

Patient characteristic data and baseline characteristics of children and parents. Data are presented as means with 95% confidence intervals for continuous data and percentages for categorical data

| Child data | |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) (M, 95% CI) | 5.5 (5.1–6.0) |

| Gender (% male) | 63 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 80 |

| African American | 9 |

| Asian American | 1 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 |

| ‘Other’ | 7 |

| Previous surgeries (% yes) | 11 |

| Baseline temperament (EASI; M, 95% CI) | |

| Emotionality | 10.8 (10.1–11.6) |

| Activity | 15.4 (14.6–16.3) |

| Sociability | 18.2 (17.6–18.8) |

| Impulsivity | 12.9 (12.1–13.6) |

| Parent data | |

| Mother age (M, 95% CI) | 35.7 (31.5–40.0) |

| Father age (M, 95% CI) | 39.7 (36.2–43.2) |

| Education (yr) (M, 95% CI) | 15.6 (14.5–16.5) |

| Marital status (% married) | 80 |

| Anxiety (STAI; M, 95% CI) | |

| Trait anxiety | 34.2 (32.9–35.7) |

| State anxiety—preoperative holding area | 39.9 (38.0–41.7) |

| State anxiety—walk to the OT | 44.4 (42.1–46.7) |

ADVANCE dismantling analyses

In order to determine the components of ADVANCE that had a significant impact on child preoperative anxiety, each separate component was entered into an anova to examine the effect on anxiety at the different assessment points. For all of the analyses, no significant effects were found for child anxiety at walk to the OT or entrance to the OT; therefore, only anxiety at holding and introduction of the anaesthesia mask are presented (Table 2). Two ADVANCE components were significantly associated with child anxiety: practise with the anaesthesia mask at home and parental use of distraction in holding. Both components also demonstrated medium effect sizes (Table 2). The dismantling analyses illustrated that parents who were adherent to the use of two or more planned distractions in the holding area had children who were less anxious then and during mask anaesthesia induction. Also, parents who engaged in mask practise with their child at home had children with significantly lower anxiety at mask introduction.

Table 2.

Child anxiety as determined by adherence to mask practise and use of distraction in holding. Statistical analyses: one-way anova. Group means, standard deviations, and P-values are presented. Effect size (Cohen's d) was calculated as was the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the population means. Adherence to distraction use was defined as following instructions to plan and use two distractions with child in holding area; non-adherence was used for fewer than two distractions or no distraction use. Adherence to mask practise was defined as completing the full shaping and exposure exercise with the anaesthesia mask with the child; non-adherence was incomplete or no mask practise

| Group | Anxiety at holding | sd | P-value | 95% confidence interval | Cohen's d | Anxiety at mask intro | sd | P-value | 95% confidence interval | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence to distraction in holding (n=38) | 30.2 | 7.8 | 0.03 | 1.1–11.8 | 0.49 | 38.2 | 18.3 | 0.01 | 3.5–20.9 | 0.58 |

| Non-adherence to distraction in holding (n=52) | 36.6 | 16.9 | 50.4 | 23.4 | ||||||

| Adherence to mask practise (n=78) | 32.8 | 12.3 | NS | −9.3 to 24.8 | 0.41 | 42.5 | 20.4 | 0.02 | 3.0–31.6 | 0.70 |

| Non-adherence to mask practise (n=10) | 40.5 | 23.6 | 59.8 | 28.7 |

Relationship between adherence and change in preoperative anxiety over time

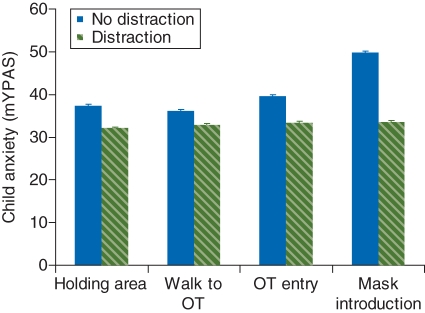

To determine the relationship between anxiety over time as a function of adherence, repeated-measures anova was conducted for both use of distraction in holding and mask practise. Regarding parental adherence to use of distraction in holding, repeated-measures anova revealed a significant interaction between phase of the preoperative procedure and distraction group F3,189=3.03, P=0.03. In addition, there was a significant between-group effect F1,63=6.09, P=0.02. Specifically, analyses indicated that anxiety scores for the high adherence to the use of distraction group were stable over time F3,69=0.20, P=0.90, but increased significantly at induction for the no distraction group F3,120=6.82, P<0.01 (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Effects of parental use of distraction on change in children's preoperative anxiety over time. Data are presented as group means at each assessment point and include standard error (se) bars.

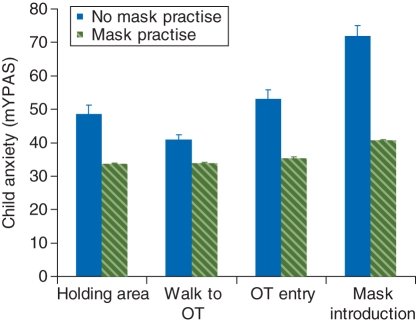

For mask practise, anova results revealed a significant interaction between phase of the preoperative procedure and adherence to mask practise, F3,183=3.36, P=0.02. In addition, there was a significant between-group effect F1,61=315.73, P<0.01. Specifically, analyses indicated that the anxiety scores for children in the adherent to mask practise at home group were relatively stable over time (increasing only at induction F3,168=3.99, P<0.01) but increased significantly from walk to OT to OT entry (P=0.05) and from OT entry to mask introduction for the no mask practise group F3,15=3.18, P=0.05 (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Effects of mask practise on change in children's preoperative anxiety over time. Data are presented as group means at each assessment point and include standard error (se) bars.

Discussion

In this follow-up dismantling report, we found that greater parental adherence to components of the ADVANCE family-centred preparation programme was associated with lower child anxiety before surgery. Through dismantling the multi-component intervention and examining each specific component independently, we determined that practising with the anaesthesia mask at home and parental planning and use of distraction in the holding area were the two components that emerged as having a significant impact on children's anxiety. However, not only did children experience significantly less preoperative anxiety when their parents were adherent to mask practise and use of distraction, their anxiety tended to remain stable and relatively low throughout the preoperative period. In contrast, those children whose parents were not adherent to these intervention components experienced escalating anxiety as they progressed from holding to introduction of the mask.

Considering the detrimental effects of preoperative anxiety on children's clinical and behavioural recovery from surgery,5,17 identification of critical components of interventions to reduce preoperative distress is needed. This is particularly important because children are seldom provided with comprehensive preoperative preparation in the hospital setting. In fact, recent research by our group illustrated that on the day of surgery, anaesthesiologists and nurses spent just minutes with families before surgery.18 Also, although presurgical sedatives, such as midazolam, are effective interventions for preoperative distress, administration is not always possible, given the timing in onset of action in the context of a busy surgical setting. Alternatively, our group developed and examined the efficacy of a comprehensive behavioural, family-centred preparation programme (ADVANCE) that was shown to be as effective as midazolam in reducing children's preoperative anxiety.6 Although this multi-component intervention was effective, parental use of distraction in the preoperative holding area and practise with the anaesthesia mask at home emerged as two components of the programme that were associated with lower child anxiety. Distraction has consistently been shown to be an effective intervention in managing children's anxiety in the medical setting.7 Similarly, mask practise at home before exposure to anaesthesia induction combines the behavioural training features of exposure to the potentially feared stimulus and shaping of the children's adaptive responses when presented with the mask in the OT before induction.7,10 These features of the ADVANCE programme seem crucial to its efficacy, and should be strongly emphasized during training.

Although this report supports the necessity of distraction and practise with the mask at home, it does not specifically address the sufficiency of those components when used alone for reducing children's preoperative anxiety. These components were presented within the context of a family-based intervention package. Additional research should address which of the other intervention components can be eliminated in an effort to streamline the intervention without detrimental effects. We also note that while most parent and child characteristic and psychological factors, such as child temperament and parent anxiety, were not associated with adherence to the treatment programme, child gender and parental education were two factors that did demonstrate such a relationship. Therefore, it may be prudent to determine whether aspects of these patient characteristic variables impacted adherence. For example, perhaps level of education was a barrier to optimally implementing the intervention and therefore may require modifications to the intervention itself.

The process of development, testing, and refinement of interventions that decrease children's preoperative anxiety includes multiple stages. Dismantling reports like this one in which necessary components are identified is a valuable step that helps inform the development of streamlined and therefore more easily disseminated interventions. This intervention refinement process is essential for the production of cost-effective interventions for reducing anxiety and anxiety-related post-surgical complications in children undergoing surgery.

This dismantling analysis is an important step in that process and highlights shaping and exposure (i.e. practise with the anaesthesia mask) and parental use of distraction in the surgical setting as two beneficial components to any preoperative preparation programme that will be designed in the future. When these particular intervention components are implemented, children are not only taken into the OT in a significantly calmer state, their anxiety remains relatively stable throughout the preoperative process. Given the strong relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative recovery, effective means of preventing high anxiety in the surgical setting are needed.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grant from the National Institutes of Health R01HD37007, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- 1.Graves E. National hospital discharge survey: annual summary. Vital Health Stat Series 13: Data from the National Health Survey. 1993;114:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeby DG, Hughes JOM. Behaviour of unsedated children in the anaesthetic room. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:279–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/52.3.279. doi:10.1093/bja/52.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kain ZN, Wang SM, Mayes LC, Caramico LA, Hofstadter MB. Distress during the induction of anesthesia and postoperative behavioral outcomes. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1042–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00013. doi:10.1097/00000539-199905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kain ZN. Postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes in children: incidence, risks factors and interventions. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2000;51:217–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Karas DE, McClain BC. Preoperative anxiety, postoperative pain, and behavioral recovery in young children undergoing surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;118:651–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2920. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:65–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00013. doi:10.1097/00000542-200701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blount RL, Zempsky WT, Jaaniste T, et al. Management of pain and distress due to medical procedures. In: Roberts M, Steele R, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. 4th Edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 171–88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chorney JM, Torrey C, Blount RL, McLaren CE, Chen W-P, Kain ZN. Healthcare provider and parent behavior and children's coping and distress at anesthesia induction. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1290–6. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c14be5. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c14be5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Kisely SA. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents: an abbreviated Cochrane review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:842–54. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn031. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLaren JE, Kain ZN. Development of a brief behavioral intervention for children's anxiety at anesthesia induction. Children's Health Care. 2008;37:196–209. doi:10.1080/02739610802151522. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buss A, Plomin R. A Temperament Theory of Personality Development. New York: Wiley-Interscience Publications; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early Developing Personality Traits. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1984. Theory and Measurement of EAS. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. State-trait Anxiety Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kain ZN, Mayes L, Cicchetti D, et al. A tool for measurement of pre-operative anxiety in children: the Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale (YPAS) Anesthesiology. 1994;81:A1361. doi:10.1097/00000542-199409001-01360. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kain Z, Mayes LC, Cicchetti DV, et al. Measurement tool for preoperative anxiety in young children: the Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale. Child Neuropsychol. 1995;1:203–10. doi:10.1080/09297049508400225. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Cicchetti DV, Bagnall AL, Finley JD, Hofstadter MB. The Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale: how does it compare with a ‘gold standard’? Anesth Analg. 1997;85:783–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00012. doi:10.1097/00000539-199710000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Maranets I, et al. Preoperative anxiety and emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1648–54. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136471.36680.97. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000136471.36680.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kain ZN, MacLaren JE, Hammell C, et al. Healthcare provider–child–parent communication in the preoperative surgical setting. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:376–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02921.x. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]