Abstract

Biosynthesis of nitrogenase FeMoco is a highly complex process that requires, minimally, the participation of nifS, nifU, nifB, nifE, nifN, nifV, nifH, nifD and nifK gene products. Previous genetic analyses have identified the essential factors for the assembly of FeMoco; however, the exact functions of these factors and the precise sequence of events during the assembly process had remained unclear until recently, when a number of the biosynthetic intermediates of FeMoco were identified and characterized by combined biochemical, spectroscopic and structural analyses. This review gives a brief account of the recent progress toward understanding the assembly process of FeMoco, which has identified some important missing pieces of this biosynthetic puzzle.

Keywords: nitrogen fixation, nitrogenase, FeMoco, biosynthesis

1. Introduction to nitrogenase

Nitrogenase provides the biochemical machinery for nitrogen fixation, an ATP-dependent process in which the atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) is converted to the bioavailable ammonia (NH3) [1–7]. The overall reaction catalyzed by nitrogenase is usually depicted as follows: N2 + 8H+ + 16MgATP + 8e− → 2NH3 + H2 + 16MgADP + 16Pi (where Pi denotes inorganic phosphate). This reaction not only represents the key entry point of reduced nitrogen into the global nitrogen cycle, but also embodies the formidable chemistry of breaking the triple bond of N2 under ambient conditions.

Four classes of nitrogenases have been identified to date, three of which are highly homologous to one another and distinguished mainly by the presence of different heterometals (molybdenum, vanadium or iron) at their respective active sites1. The “conventional” molybdenum (Mo) nitrogenase of Azotobacter vinelandii consists of two component proteins, the iron (Fe) protein (encoded by nifH) and the molybdenum-iron (MoFe) protein (encoded by nifD and nifK). The homodimeric Fe protein is bridged by a single [4Fe–4S] cluster between the subunits and contains one ATP binding site within each subunit; whereas the α2β2-tetrameric MoFe protein contains two unique clusters per αβ-dimer: the P-cluster (an [8Fe–7S] cluster), which is located at the α/β-subunit interface; and the FeMoco (a [Mo–7Fe–9S–X–homocitrate] cluster, where X is considered to be C, N or O), which is positioned within the α-subunit [9, 10]. The catalysis of nitrogenase involves complex association/dissociation between the Fe protein and the MoFe protein, and the sequential, inter-protein transfer of electrons from the [4Fe–4S] cluster of the Fe protein, through the P-cluster, to the FeMoco of the MoFe protein, where substrate is reduced (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

X-ray crystal structure of half of the ADP•AlF4−-stabilized Fe protein/MoFe protein complex (A) and the relative positions of components in the complex that are involved in the electron flow during catalysis (B) [11]. The identical subunits of Fe protein are shown in yellow and orange, and the α- and β-subunits of MoFe protein are shown in light and dark blue, respectively. The atoms of the components within the Fe protein/MoFe protein complex are colored as follows: Fe, purple; S, yellow; O, red; C, gray; Mg, dark blue; Al, yellow; F, light blue.

2. Biosynthesis of nitrogenase FeMoco

There is substantial interest in elucidating the biosynthetic mechanism of the FeMoco of nitrogenase, because this unique cofactor is not only biologically important, but also chemically unprecedented2. Biosynthesis of FeMoco is a highly complicated process that requires, at least, the participation of nifS, nifU, nifB, nifE, nifN, nifV, nifH, nifD and nifK gene products. Based on genetic evidence, FeMoco assembly is likely initiated by the actions of NifS and NifU (encoded by nifS and nifU), which mobilizes Fe and S for the biogenesis of small Fe–S fragments [21–25]. These small Fe–S fragments are subsequently transferred to NifB (encoded by nifB) and processed into a FeMoco core, which is then transferred to NifEN (encoded by nifE and nifN) and undergoes additional rearrangements before it is delivered to the MoFe protein [26–29]. Thus, the flow of Fe and S during the biosynthesis of FeMoco is likely as follows: NifUS → NifB → NifEN → MoFe protein [26]. Other important players in FeMoco biosynthesis include NifV (encoded by nifV), the homocitrate synthase that supplies homocitrate for the biogenesis of FeMoco [30, 31]; NifQ (encoded by nifQ), a protein factor that is likely involved in the storage and/or mobilization of Mo for FeMoco assembly [32, 33]; and Fe protein, the catalytic electron donor for MoFe protein that is also crucial for the maturation of FeMoco [26]. Although the biosynthetic factors of FeMoco have been successfully mapped out earlier, the exact functions of these factors and the precise sequence of events during the assembly process had remained unclear until the recent characterization of a number of the biosynthetic intermediates of FeMoco by combined biochemical, spectroscopic and structural analyses. This review gives a brief account of the recent progress toward understanding the assembly process of FeMoco, which provides significant insights into this biosynthetic “black box”.

2.1. NifU, NifS and NifB: Machineries for FeMoco core formation

NifS and NifU are responsible for generating small building blocks for FeMoco assembly. NifS is a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent cysteine desulphurase, which forms a protein-bound cysteine persulphide that is subsequently donated to NifU for the sequential formation of [2Fe–2S] and [4Fe–4S] clusters (Fig. 2) [25, 34]. These small Fe–S clusters are then transferred to NifB and processed into a large Fe–S core that possibly contains all Fe and S required for the generation of a mature cofactor [27]. The exact function of NifB in this process is unclear. Nevertheless, NifB is indispensable for FeMoco biosynthesis, as deletion of nifB leads to the formation of a cofactor-deficient form of MoFe protein [35]. Sequence analysis shows that NifB contains a CXXXCXXC signature motif at the N-terminus, which is characteristic of a family of radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent enzymes [26, 36]. Apart from this feature, there is an abundance of potential ligands in the NifB sequence for the coordination of the entire complement of Fe atoms of FeMoco [26]. Therefore, generation of the Fe–S core on NifB could represent a novel synthetic route to bridged metal clusters that relies on radical chemistry at the SAM domain of NifB. It can be speculated that NifB links two [4Fe–4S] subcubanes by a S atom and an interstitial atom, X, thereby generating a fully complemented Fe–S scaffold (Fig. 2) that could be rearranged into the core structure of FeMoco. Although it is unclear whether the rearrangement of the Fe–S scaffold occurs prior to its exit from NifB, the cluster species synthesized on NifB is subsequently delivered to NifEN for further processing (see below).

Fig. 2.

Biosynthesis of FeMoco core by NifS, NifU and NifB. (A) Sequence of events during the assembly process of the Fe–S core of FeMoco. The combined action of NifU–NifS generates small Fe–S fragments on NifU (steps ➀ and ➁), which are used as building blocks for the formation of a large Fe–S core on NifB (step ➂). The permanent metal centers of the scaffold proteins are colored gray, with [2Fe–2S] and [4Fe–4S] clusters shown as diamonds and cubes, respectively. The transient cluster intermediates are colored yellow. (B) Structures of the cluster intermediates during the assembly process of the Fe–S core of FeMoco. Shown are the cluster types that were identified (on NifU) or proposed (for NifB). Hypothetically, NifB could bridge two [4Fe–4S] clusters by inserting a S atom along with an interstitial atom, X, thereby generating an Fe–S scaffold that could be rearranged later into a precursor of the FeMoco that closely resembles the core structure of the mature cofactor (see Fig. 3, ➀). The atoms are colored as follows: Fe, purple; S, yellow; X, light gray.

2.2. NifEN and Fe protein: Factors for FeMoco maturation

Upon completion, the FeMoco core is delivered from NifB to NifEN. The function of NifEN as a scaffold protein for the maturation of FeMoco was initially proposed on the basis of a significant level of sequence homology between NifEN and MoFe protein, which has led to the hypothesis that NifEN contains cluster binding regions analogous to the P-cluster and FeMoco sites in the MoFe protein [26, 28, 29, 37]. While the P-cluster analog in NifEN was established earlier as a [4Fe–4S]-type of cluster [29], the identity of the FeMoco analog has remained unknown until the recent characterization of a NifEN complex isolated from the nifB-intact yet nifHDK-deficient background [38]. The absence of the nifDK-encoded MoFe protein (the terminal acceptor of FeMoco) and the nifH-encoded Fe protein (an essential factor for FeMoco maturation) allows the accumulation of a precursor form of FeMoco on NifEN. This NifEN-bound precursor is free of Mo and homocitrate [38], and Fe K-edge x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)/extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis reveals that it closely resembles the Fe–S core of the mature FeMoco despite slightly elongated inter-atomic distances (Fig. 3) [39]. This finding suggests that, instead of coupling the [4Fe–3S] and [Mo–3Fe–3S] sub-clusters into a mature cofactor, the FeMoco is assembled by having the complete Fe–S core structure in place before the incorporation of Mo and homocitrate.

Fig. 3.

Maturation of FeMoco on NifEN. (A) Sequence of events during the maturation process of the FeMoco. Maturation of FeMoco on NifEN starts with a Mo/homocitrate-free FeMoco precursor (step ➀), which is rearranged from the Fe–S scaffold synthesized on NifB (see Fig. 2, ➂). Such an Fe-only precursor can be converted to a mature FeMoco on NifEN upon Fe protein-mediated insertion of Mo and homocitrate (step ➁). Following the completion of FeMoco assembly on NifEN, FeMoco is delivered to its destined location in the MoFe protein (step ➂). The permanent metal centers of the scaffold proteins are colored gray, with the [4Fe–4S] clusters and P-clusters shown as cubes and ovals, respectively. The transient cluster intermediates are colored yellow. Mo, molybdenum; HC, homocitrate. (B) Structures of cluster intermediates during the maturation process of FeMoco. Shown are the cluster types that were identified on NifEN and MoFe protein. Although both 7Fe and 8Fe models have been proposed for the NifEN-associated precursor [39], only the 8Fe model is shown here. The atoms are colored as follows: Fe, purple; S, yellow; Mo, light blue; C, gray; O, red; X, light gray. (C and D) EPR spectra of precursor-bound NifEN (brown lines), FeMoco-bound NifEN (green lines) and MoFe protein (blue lines) in the dithionite-reduced (C) and IDS-oxidized (D) states. The g-values are indicated. IDS, indigo disulfonate.

The precursor on NifEN can be transformed, in vitro, into a fully complemented cofactor upon incubation with Fe protein, MgATP, molybdate (MoO42−) and homocitrate (Fig. 3) [40]. Such a process can be monitored by the spectral changes in the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis of NifEN. In the dithionite-reduced state, the conversion of precursor results in the disappearance of the precursor-associated S = 1/2 signal3 and the concurrent appearance of a small, FeMoco-like signal in the S = 3/2 region (Fig. 3C); whereas in the indigo disulfonate (IDS)-oxidized state, the maturation of cluster results in the nearly complete disappearance of the precursor-specific g = 1.92 signal3 (Fig. 3D). The Fe and Mo K-edge XAS/EXAFS spectroscopy [40] reveals that the FeMoco on NifEN is nearly indistinguishable in structure from the native cofactor in MoFe protein (Fig. 3B), except for a somewhat asymmetric coordination of the Mo atom that is likely due to the presence of a different ligand environment at the Mo end of the cofactor. Maturation of the NifEN-associated precursor is strictly dependent on ATP hydrolysis, as cofactor maturation cannot occur if ATP is substituted with ADP or nonhydrolyzable ATP analogs, or if the wild-type Fe protein is replaced by Fe protein mutants defective in MgATP hydrolysis [40, 41]. In addition, the efficiency of FeMoco maturation on NifEN is dependent on the dithionite concentration, as a 3 to 4 fold of increase in cofactor maturation can be observed upon an increase of dithionite concentration from 2 mM to 20 mM [42]. Considering that the Fe protein is the only known ATP-dependent reductase in the in vitro maturation assay, these observations point to a significant role of Fe protein in FeMoco maturation.

Subsequent analysis of the Fe protein re-isolated after the incubation with NifEN, MoO42−, homocitrate and MgATP shows that it is “loaded” with Mo and homocitrate, which can be subsequently inserted into the precursor on NifEN (Fig. 4) [41]. The Mo K-edge XAS spectrum of the loaded Fe-protein (Fig. 4B) demonstrates a decreased number of Mo=O bonds (two or three instead of the four found in MoO42−) and a reduction in the effective oxidation state of Mo, which is caused by either a change in the formal oxidation state of Mo or a change in the ligation of Mo atom. Interestingly, the EPR spectrum of loaded Fe protein (Fig. 4C) assumes a line shape intermediary between those of the MgADP- and MgATP-bound states of the Fe protein [41]. This observation is in line with the first crystal structure of the ADP-bound form of Fe protein, which reveals the attachment of Mo at a position that corresponds to the γ-phosphate of ATP [43]. Such a pattern of ADP/Mo-binding (Fig. 4A) may represent the initial association of Mo to the Fe protein, particularly given the structural analogy between phosphate and molybdate4. Indirect evidence for the sequence of Mo and homocitrate attachment to Fe protein came from the biochemical analyses of a "FeMo" cluster-bound form of NifEN (generated by incubating NifEN with Fe protein, ATP and MoO42− alone). Such a homocitrate-deplete, yet Mo-replete form of cofactor cannot be further matured into FeMoco upon incubation with homocitrate, suggesting that homocitrate is likely attached simultaneously with Mo to the Fe protein [45]. Once the loading of Fe protein is completed, it likely interacts with NifEN in a manner that is analogous to its interaction with the homologous MoFe protein during substrate turnover (see Fig. 1), during which process Mo and homocitrate are incorporated into the NifEN-bound precursor.

Fig. 4.

Mobilization of Mo and homocitrate by Fe protein. (A) In the presence of reductant, Mo (shown as a blue sphere) and homocitrate (HC, shown as a ball-and-stick model) can be “loaded” onto the Fe protein upon ATP hydrolysis. Mo may enter the Fe protein by attaching to the position that corresponds to the γ-phosphate of ATP following the hydrolysis of ATP. Subsequently, the loaded Fe protein delivers Mo and homocitrate to the NifEN-associated precursor and transforms the precursor into a fully matured FeMoco (see Fig. 3A). The [4Fe–4S] cluster of the Fe protein is represented by a gray cube. The modification of Mo upon loading is indicated by a change of the color from dark blue (free Mo) to light blue (bound Mo). (B) Normalized Mo K-edge x-ray absorption spectra of molybdate (left) and Fe protein loaded with Mo and HC (right). A reference line is drawn at 20020 eV for the comparison of edge position. (C) EPR spectra of the MgATP-bound Fe protein (left) and the Fe protein loaded with Mo and HC (right).

2.3. MoFe protein: Receptor for matured FeMoco

Following the maturation of FeMoco on NifEN, the cofactor is delivered from its assembly site in NifEN to its target binding site in the MoFe protein. The absolute requirement of intermediary FeMoco carrier(s) between NifEN and MoFe protein was precluded by the previous observation of unaffected nitrogen-fixing activity of the host upon deletions of proposed carrier-encoding gene(s) [46] and the recent finding of direct FeMoco transfer between NifEN and MoFe protein upon protein–protein interactions [40]. Thus, the factors previously hypothesized as FeMoco carriers may instead serve as post-translational modifiers that fine tune the key residue(s) in the protein(s) for cluster formation, or as chaperones that stabilize the protein complex and/or reposition the proteins in a favourable orientation for FeMoco transfer. Recently, one such factor, NifX, has been shown to act in a chaperone-like manner in FeMoco assembly [47]. In addition to the nif-encoded accessory proteins, the well-established chaperone, GroEL, has also been demonstrated to facilitate the insertion of FeMoco into the MoFe protein [48].

The docking of NifEN on the MoFe protein is signalled by the completion of the FeMoco assembly on NifEN. Contrary to the precursor-associated NifEN, the FeMoco-bound NifEN forms a complex with the MoFe protein (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the maturation of cofactor on NifEN is accompanied by a conformational change of the protein that is necessary for its subsequent docking on the MoFe protein [45]. Interestingly, NifEN carrying a "FeMo" cluster (the homcitrate-free homolog of FeMoco) can also form a complex with the MoFe protein (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the incorporation of Mo alone into the NifEN-bound precursor is sufficient to trigger the conformational change of the protein; yet, such a cluster cannot be subsequently transferred to the MoFe protein, likely due to the absence of the negative homocitrate moiety that is crucial for the insertion of the cluster into a positively charged “funnel” in the MoFe protein (see below) [45]. Sequence comparison between NifEN and MoFe protein reveals the presence of similar cofactor binding sites in the two proteins; however, certain residues that either provide a covalent ligand or tightly pack FeMoco within the polypeptide matrix of MoFe-protein are not duplicated in the corresponding NifEN sequence [26]. It is possible, therefore, that the respective cluster sites in NifEN and MoFe protein are brought in close proximity upon the complex formation between the two proteins, which allows the subsequent “diffusion” of FeMoco from its biosynthetic site in NifEN (low affinity site) to its binding site in MoFe protein (high affinity site).

Fig. 5.

Incorporation of FeMoco into the MoFe protein. (A) Upon the Fe protein-mediated insertion of Mo and homocitrate (HC), the precursor on NifEN is converted to a fully matured FeMoco. The completion of the maturation of FeMoco on NifEN is accompanied by a conformational rearrangement, which enables the docking of NifEN on the MoFe protein. Subsequently, FeMoco is transferred from its assembly site in NifEN to its target binding site within the MoFe protein upon direct protein-protein interactions. Charge-based interactions likely play an important role in the transfer of FeMoco between NifEN and the MoFe protein, during which process the negatively charged FeMoco is inserted into the MoFe protein via a positively charged insertion funnel. For the purpose of simplicity, the interactions between one cofactor assembly site in NifEN and one cofactor binding site in MoFe protein are shown. The permanent metal centers of the scaffold proteins are colored gray, with the [4Fe–4S] clusters and P-clusters shown as cubes and ovals, respectively. The transient cluster intermediates are colored yellow. (B) A NifEN-associated “FeMo” cluster can be formed by omitting the homocitrate in the maturation process. The insertion of Mo into the precursor induces a conformational change that allows the complex formation between NifEN and the MoFe protein. However, the lack of a sufficient amount of negative charges of the “FeMo” cluster (due to the absence of the negative homocitrate moiety) results in an attempted, yet unsuccessful insertion of the cluster into the positive funnel of MoFe protein.

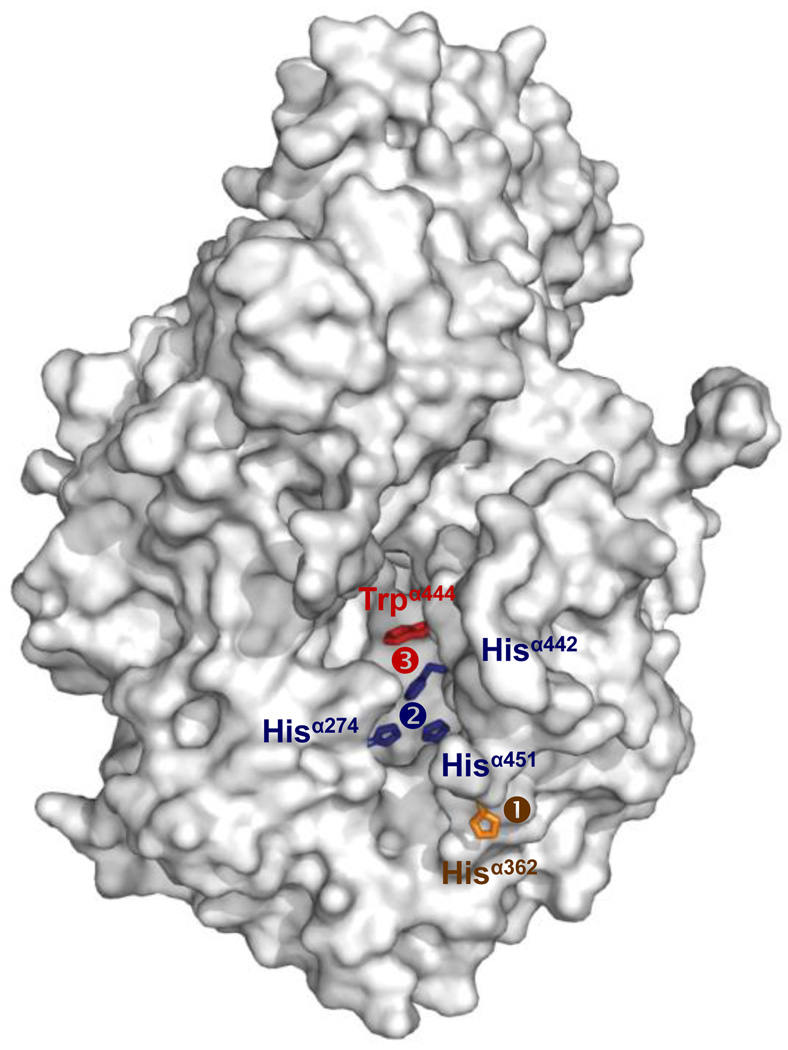

Once it “diffuses” out of NifEN and reaches the surface of the MoFe protein, FeMoco interacts with a number of MoFe protein residues en route to its target location. Identification of these residues was facilitated by the crystallographic analysis of a P-cluster-intact but FeMoco-deficient form of MoFe protein (isolated from the nifB-deletion background), which reveals the presence of a positively charged funnel in the α-subunit that is of sufficient size to accommodate the insertion of the negatively charged FeMoco [35]. Three regions that are potentially important for FeMoco insertion can be identified within this funnel: (1) a “lid loop” (residues α353 through α364) and, in particular, Hisα362 (located at the tip of the loop), which could serve as a transient ligand for FeMoco at the entrance of the funnel (Fig. 6, ➀); (2) a “His triad” (Hisα274, Hisα442 and Hisα451), which may provide an intermediary docking point for FeMoco half way down the funnel (Fig. 6, ➁); and (3) a “switch/lock” (Hisα442 and Trpα444), which could secure the FeMoco in its binding site by the bulky side chain of Trpα444 following a switch in positions between Trpα444 and Hisα442 at the bottom of the funnel (Fig. 6, ➂) [26, 35]. Participation of these residues in the FeMoco insertion process has been confirmed by mutational analyses, which demonstrate a specific and substantial reduction of FeMoco incorporation upon removal of the positive charge, ligand capacity and steric effect at these positions [49–51]. Furthermore, small angle scattering analysis shows that the Rg value of the FeMoco-deficient MoFe protein (42.4 Å) is slightly, yet reproducibly larger than that of the wild-type MoFe protein (40.2 Å) [52], indicating that the former has a more relaxed conformation. Considering that the FeMoco-deficient MoFe protein likely represents the biosynthetic intermediate right before the holo MoFe protein, these observations suggest that the MoFe protein is compacted upon the insertion of FeMoco.

Fig. 6.

Surface representation of the FeMoco-deficient ΔnifB MoFe protein. The key residues for FeMoco insertion (illustrated as sticks) can be found lining a positively charged insertion funnel from the entrance to the bottom, including ➀ the “lid-loop” residue, Hisα362 (colored yellow), which likely provides the first docking point for FeMoco at the entrance of the insertion funnel; ➁ the “His-triad” residues, Hisα274, Hisα442 and Hisα451 (colored blue), which potentially provide an intermediary docking point for FeMoco during the insertion process; and ➂ the “switch/lock” residues, Hisα442 and Trpα444 (colored red), which eventually secure the FeMoco by the bulky side chain of Trpα444 through a switch in positions between the two residues at the bottom of the insertion funnel.

3. Concluding remarks

There has been major progress toward elucidating the biosynthetic mechanism of FeMoco during the recent years; however, the job of piecing together this biological puzzle is far from completion. The biosynthetic events that occur prior to NifEN, in particular, those hosted by NifB, remain largely unknown. Moreover, the interactions between proteins during the cluster transfer process, as well as the functions of the accessory factors in each biosynthetic step, have not been well explored. Further advances toward a comprehensive understanding of the biosynthesis of FeMoco will depend on a combination of biochemical, spectroscopic and structural studies that clearly define the network of interactions among the various assembly factors of this unique cluster.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM-67626 (M.W.R.).

Abbreviations

- Fe protein

iron protein

- MoFe protein

molybdenum-iron protein

- FeMoco

iron-molybdenum cofactor

- XAS

x-ray absorption spectroscopy

- EXAFS

extended x-ray absorption fine structure

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The fourth nitrogenase is superoxide-dependent and apparently different from the other nitrogenase classes [8].

Recently, significant progress has been made in the chemical synthesis of P-cluster topologs [12–20].

The S = 1/2 signal in the EPR spectrum of dithionite-reduced NifEN is a mixture of signals originating from both the [4Fe–4S] cluster and the precursor, which can be distinguished by their different behaviors upon variations of temperature and power [38]. Upon Mo insertion, the portion of the S = 1/2 signal that originates from the precursor (~50%) disappears, whereas the portion of the S = 1/2 signal that originates from the [4Fe–4S] cluster (~50%) remains [40]. The g = 1.92 feature has been assigned to the precursor based on the presence of this signal in the spectrum of the IDS-oxidized NifEN (which contains both the precursor and the [4Fe–4S] cluster) and the absence of this signal from the spectrum of the IDS-oxidized ΔnifB NifEN (which contains only the [4Fe–4S] cluster) [38].

Remarkably, similar nucleotide-assisted processes have been proposed for the insertion of Mo into the pterin-based cofactors [44].

References

- 1.Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2983. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard JB, Rees DC. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2965. doi: 10.1021/cr9500545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith BE. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 1999;47:159. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rees DC, Tezcan FA, Haynes CA, Walton MY, Andrade SL, Einsle O, Howard JB. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2005;363:971. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard JB, Rees DC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2006;103:17088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603978103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters JW, Szilagyi RK. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribbe M, Gadkari D, Meyer O. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einsle O, Tezcan FA, Andrade SL, Schmid B, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Science. 2002;297:1696. doi: 10.1126/science.1073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Rees DC. Nature. 1992;360:553. doi: 10.1038/360553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schindelin H, Kisker C, Schlessman JL, Howard JB, Rees DC. Nature. 1997;387:370. doi: 10.1038/387370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groysman S, Holm RH. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2310. doi: 10.1021/bi900044e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hlavinka ML, Miyaji T, Staples RJ, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:9192. doi: 10.1021/ic701070w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berlinguette CP, Miyaji T, Zhang Y, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:1997. doi: 10.1021/ic051770k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:674. doi: 10.1021/ic030259t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3910. doi: 10.1021/ja0214633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuo JL, Zhou HC, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:4624. doi: 10.1021/ic0301369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohki Y, Imada M, Murata A, Sunada Y, Ohta S, Honda M, Sasamori T, Tokitoh N, Katada M, Tatsumi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13168. doi: 10.1021/ja9055036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohki Y, Ikagawa Y, Tatsumi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10457. doi: 10.1021/ja072256b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohki Y, Sunada Y, Honda M, Katada M, Tatsumi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4052. doi: 10.1021/ja029383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frazzon J, Dean DR. Met. Ions. Biol. Syst. 2002;39:163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuvaniyama P, Agar JN, Cash VL, Johnson MK, Dean DR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agar JN, Yuvaniyama P, Jack RF, Cash VL, Smith AD, Dean DR, Johnson MK. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000;5:167. doi: 10.1007/s007750050361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dos Santos PC, Smith AD, Frazzon J, Cash VL, Johnson MK, Dean DR. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AD, Jameson GNL, Dos Santos PC, Agar JN, Naik S, Krebs C, Frazzon J, Dean DR, Huynh BH, Johnson MK. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12955. doi: 10.1021/bi051257i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dos Santos PC, Dean DR, Hu Y, Ribbe MW. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1159. doi: 10.1021/cr020608l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen RM, Chatterjee R, Ludden PW, Shah VK. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roll JT, Shah VK, Dean DR, Roberts, GP GP. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodwin PJ, Agar JN, Roll JT, Roberts GP, Johnson MK, Dean DR. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10420. doi: 10.1021/bi980435n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoover TR, Robertson AD, Cerny RL, Hayes RN, Imperial J, Shah VK, Ludden PW. Nature. 1987;329:855. doi: 10.1038/329855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng LM, White RH, Dean DR. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:5963. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5963-5966.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imperial J, Ugalede RA, Shah VK, Brill WJ. J. Bacteriol. 1984;158:187. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.187-194.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez JA, Curatti L, Aznar CP, Perova Z, Britt RD, Rubio LM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:11679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803576105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson DC, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid B, Ribbe MW, Einsle O, Yoshida M, Thomas LM, Dean DR, Rees DC, Burgess BK. Science. 2002;296:352. doi: 10.1126/science.1070010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curatti L, Ludden PW, Rubio LM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601115103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brigle KE, Weiss MC, Newton WE, Dean DR. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:1547. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1547-1553.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu Y, Fay AW, Ribbe MW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbett MC, Hu Y, Fay AW, Ribbe MW, Hedman B, Hodgson KO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507853103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu Y, Corbett MC, Fay AW, Webber JA, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Ribbe MW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602647103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu Y, Corbett MC, Fay AW, Webber JA, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Ribbe MW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602651103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshizawa JM, Blank MA, Fay AW, Lee CC, Wiig JA, Hu Y, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Ribbe MW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9321. doi: 10.1021/ja9035225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Georgiadis MM, Komiya H, Chakrabarti P, Woo D, Kornuc JJ, Rees DC. Science. 1992;257:1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1529353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz G, Mendel RR, Ribbe MW. Nature. 2009;460:839. doi: 10.1038/nature08302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fay AW, Blank MA, Yoshizawa JM, Lee CC, Wiig JA, Hu Y, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Ribbe MW. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:3124. doi: 10.1039/c000264j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubio LM, Rangaraj P, Homer MJ, Roberts GP, Ludden PW. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernandez JA, Igarashi RY, Soboh B, Curatti L, Dean DR, Ludden PW, Rubio LM. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ribbe MW, Burgess BK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101119498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu Y, Fay AW, Schmid B, Makar B, Ribbe MW. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu Y, Fay AW, Ribbe MW. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007;12:449. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fay AW, Hu Y, Schmid B, Ribbe MW. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007;101:1630. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corbett MC, Hu Y, Fay AW, Tsuruta H, Ribbe MW, Hodgson KO, Hedman B. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8066. doi: 10.1021/bi7005064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]