Abstract

We developed a multicolor neuron labeling technique in Drosophila melanogaster combining the power to specifically target different neural populations with the label diversity provided by stochastic color choice. This adaptation of vertebrate Brainbow uses recombination to select one of three epitope-tagged proteins detectable with immunofluorescence. Two copies of this construct yield six bright, separable colors. Here we use Drosophila Brainbow to show the innervation patterns of multiple antennal lobe projection neuron lineages in the same preparation and to observe the relative trajectories of individual aminergic neurons. Nerve bundles, and even individual neurites hundreds of microns long, can be followed with definitive color labeling. We trace motor neurons in the subesophageal ganglion and correlate them to neuromuscular junctions to show their specific proboscis muscle targets. The ability to independently visualize multiple lineage or neuron projections within the same preparation greatly advances the goal of mapping how neurons connect into circuits.

Introduction

The ability to label individual neurons in their entirety and to trace their dendritic and axonal processes within the brain has been a critical neuroanatomical underpinning for studies of how neural circuits drive behavior. Original techniques for neuron labeling included Golgi staining and dye injection1. Modern methods in Drosophila melanogaster have made use of genetic tools, from lacZ enhancer trapping to binary expression systems such as upstream activating sequence (UAS)-GAL4 that allow precise targeting of exogenous reporters to defined groups of neurons (reviewed in2, 3). It is possible to target individual neurons or groups related by common origin (neuronal lineages made up of the progeny of a given neuroblast stem cell) using stochastic recombination events with MARCM or Flp-Out techniques. The ability to dissect complex expression patterns by labeling multiple individual neurons or lineages in different colors facilitates the study of how neurons interact with each other. Combinations of fluorescent reporters controlled by different binary expression systems4 and twin-spot MARCM5 have made it possible to visualize two populations of neurons in different colors. In 2007, Livet et al. 1, 6 published the Brainbow technique, a strategy for labeling many neurons in a mouse brain in distinct fluorescent colors. This enabled them to watch how different neurons interact and to visualize individual neurons in relation to each other in the same preparation.

We have combined one of the multicolor labeling techniques of Brainbow (Brainbow-1) with the genetic targeting tools from Drosophila melanogaster to differentiate lineages and individual neurons within the same brain. We have systematically tested fluorescent proteins in the adult fly brain to choose optimal color combinations. We also developed a variation of the Brainbow technique relying on antibody labeling of epitopes rather than endogenous fluorescence; this amplifies weak signal to trace fine processes over long distances. The use of spectrally discrete, photostable, narrow-bandwidth small molecule dyes also makes color assignment much simpler than with the broad excitation and emission spectra of fluorescent proteins. This approach (“dBrainbow”) speeds up characterization of individual neurons, and more importantly allows examination of individual cells in relation to each other. These features make it possible to address outstanding questions about how lineages contribute to neural circuits and about how the neurites of adjacent cells partition the areas they innervate in a stereotyped manner. We validate dBrainbow by comparing our results to published findings about antennal lobe projection neuron lineages and single octopaminergic neurons. Then we use dBrainbow to map individual motor neuron cell bodies in the subesophogeal ganglion to their proboscis muscle targets.

Results

Construct design and optimization of fluorescence

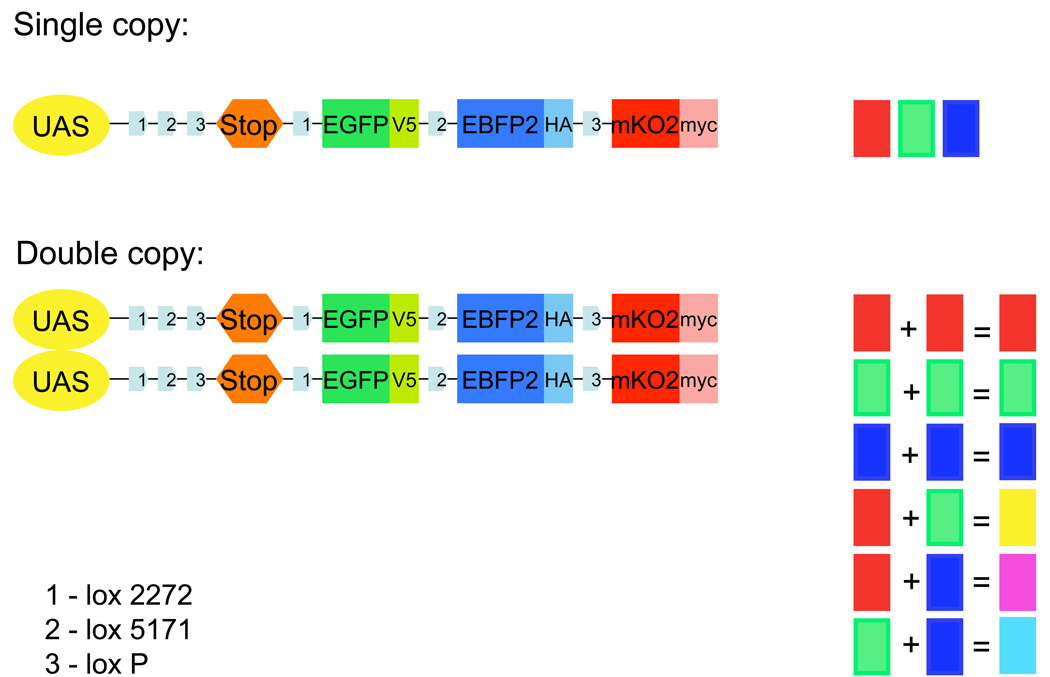

dBrainbow consists of a reporter construct that can be targeted to particular groups of neurons and can then randomly generate one of four outcomes: no-color, green, red, or blue fluorescence. The dBrainbow construct (Fig. 1) contains a transcriptional stop sequence followed by genes encoding three cytoplasmic fluorescent proteins. These four cassettes are flanked by pairs of mutually exclusive lox sites that function in Drosophila melanogaster.. In the presence of Cre recombinase, recombination occurs between one of the matched pair of lox sites and results in the irreversible selection of one of the fluorescent proteins. The UAS-dBrainbow construct is inserted into defined loci on the second and third chromosomes (attP2 and attP40); fly stocks carrying both chromosomes allow the production of six color combinations (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of the dBrainbow construct.

UAS-dBrainbow contains a UAS (upstream activating sequence) that allows its expression to be cell-specifically controlled by the presence of GAL4. There are three lox sites (pale blue arrows); Cre recombination occurs only between matched lox sites. The selection of lox site recombination in a given cell is stochastic. In the absence of recombinase, no fluorescent proteins are made because of a stop cassette with three-frame translation terminators and an SV40 poly-adenylation signal. Recombination between lox2272 sites (1), removes this stop cassette and permits expression of EGFP-V5. Recombination between the lox5171 sites (2), results in expression of EBFP2-HA, and recombination between loxP (3), produces mKO2-Myc. Cre recombination is irreversible. Colors from one or two copies of the UAS-dBrainbow construct are shown at right. All fluorescent proteins are cytoplasmic and epitope-tagged as indicated. Complete construct sequence available on request.

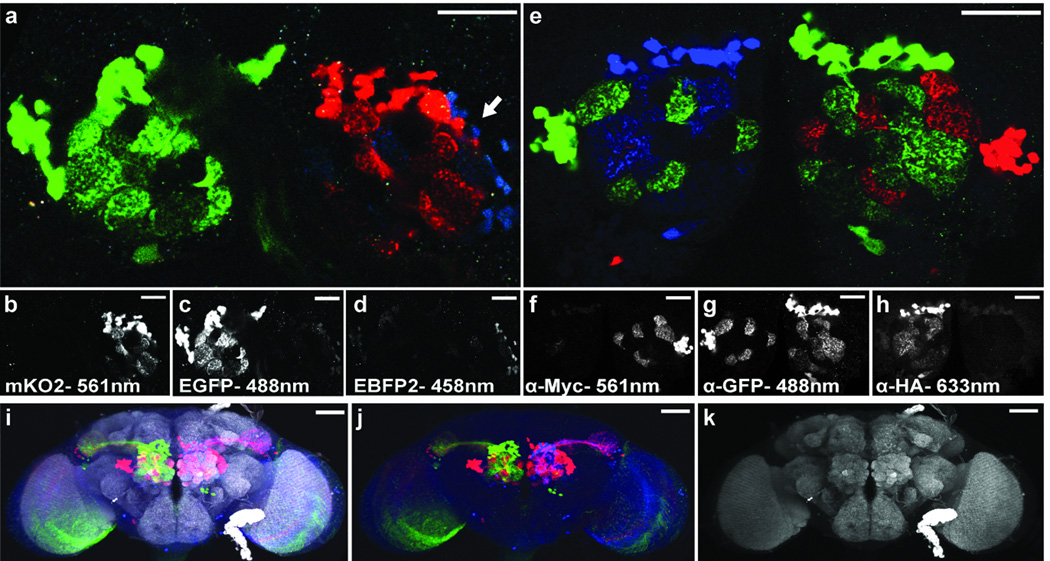

We are able to use the same construct for imaging live samples with endogenous fluorescence and fixed samples using fluorescently labeled antibodies against the epitopes attached to each fluorescent protein (Fig. 2). Live imaging requires bright, photostable, spectrally separable fluorescent proteins. Derivatives of green and red fluorescent proteins (GFP and dsRed or mRFP) are commonly used in flies. We performed an extensive search for additional spectrally separable fluorescent proteins (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1.) and identified a superior orange-red fluorescent protein, mKO27, but were unable to find proteins with good endogenous fluorescence emission in either blue or far-red. We nonetheless tried EBPF28, with EGFP and mKO2, and constructed UAS-dBrainbow (Fig. 1). An unfixed brain with a single copy of UAS-dBrainbow expressed in 3 projection neuron (PN) lineages of the adult antennal lobe (AL) showed separable red and green fluorescence even in small neurites, but unfortunately blue was only weakly detectable (Fig. 2a–d). Further improvements to the fluorescent protein superfamily may provide better options for imaging endogenous fluorescence in the future. This led us to focus our optimization efforts on the use of epitope tags and antibodies.

Figure 2. Comparison of endogenous and antibody-based fluorescence of UAS-dBrainbow flies.

(a–e) show projections of two 1 µm slices through the antennal lobes from adult brains of hs-Cre; GH146-GAL4; UAS-dBrainbow flies. (a) This sample was dissected and imaged without fixation. The endogenous fluorescence of EGFP and mKO2 are visible as green and red in the merged image; the EBFP2 (white arrow) is only weakly visible, and there is some bleed-through from the GFP channel. Blue fluorescence is more visible in a total projection (not shown). (b–d) show raw grey-scale images; the fluorescent protein and laser used are indicated below. Spectral separation is apparent from the lack of co-expression or overlap between individual channels. (e) Flies of the same genotype were stained with primary antibodies raised against EGFP, Myc, and HA and secondary antibodies coupled to AlexaFluor488, 568, and 633 respectivelyk as indicated (f–h.) All three colors are visible and there is no channel overlap, demonstrating the lack of cross-reactivity between antibodies and the good spectral separation between the AlexaFluor dyes. (i–k) Whole brains (maximum intensity projections of 20× confocal stacks) labeled with the nc82 antibody as a neuropil marker (grey), mKO2 endogenous fluorescence (red), and antibodies against EGFP (green) and HA (blue) are shown. (j) shows the fluorescent proteins alone and (k) shows the nc82 alone. Scale bars 50 µm.

Epitope tags and antibodies allow spectral separation

We needed a set of small epitopes expressible as fusions to soluble proteins, primary antibodies that recognize these epitopes with high affinity and specificity and can penetrate fixed tissue well, and secondary antibodies labeled with bright, spectrally discrete dyes (e.g. AlexaFluors). While there are many antibody-epitope combinations available for biochemical applications, only a few are routinely used for Drosophila melanogaster immunohistochemistry. A major limitation for simultaneous color visualization is the number of distinct species in which primary antibodies are available. We explored primary antibodies generated in mouse, rabbit, rat, goat, and chicken (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). Antibodies that performed well in a GAL4 line with strong expression (GH146-GAL4) were then used on a sparser line (a81-GAL4; JHS unpublished enhancer trap in CG13432) to provide a more stringent test; some of the antibodies – against V5 and HA - performed as well as the widely used anti-GFP and anti-CD8 antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition to allowing the best options to be selected for the dBrainbow construct, this effort expands the options for other experiments that require multiple distinctly labeled transgenes to be imaged in the same fly.

We selected the V5, HA, and Myc epitopes for the UAS-dBrainbow construct (Fig. 1). Because we have observed endogenous fluorescence, especially from mKO2, that survives the longer fixation for the epitope staining procedure, we chose secondary antibodies in the same spectral domain as the endogenous fluorescent proteins. Antibody staining of UAS-dBrainbow expressed in olfactory projection neurons reveals three distinct colors (Fig. 2e–h). For applications involving fixed tissue, the antibody-based method has superior performance to the endogenous fluorescence.

It is possible to combine endogenous fluorescence and antibody-based staining in the same preparation. Endogenous orange-red fluorescence from mKO2 can be combined with antibody staining against EGFP (green) and EBPF2-HA (blue), and nc82 (grey; Fig. 2i–k). This results in four distinct imaging channels and allows the inclusion of a neuropil reference marker to assist in identifying unlabeled glomeruli or for registering different preparations onto a common coordinate system.

Subdividing complex GAL4 expression patterns

GAL4 lines that target expression of reporters to specific groups of neurons have been instrumental for dissecting neuroanatomy and connectivity within the fly brain, but often produce complex expression patterns. Since it is unlikely that individual neurons are uniquely specified by their gene expression profiles alone, there is a limit to the cellular resolution the GAL4 lines can provide. Random Flp-Out methods can subdivide these patterns9, but results from different animals must then be compared to reconstruct the entire pattern. Combining GAL4 lines with the stochastic color choice of UAS-dBrainbow provides a way to perform this neuron-by-neuron subdivision within the same preparation.

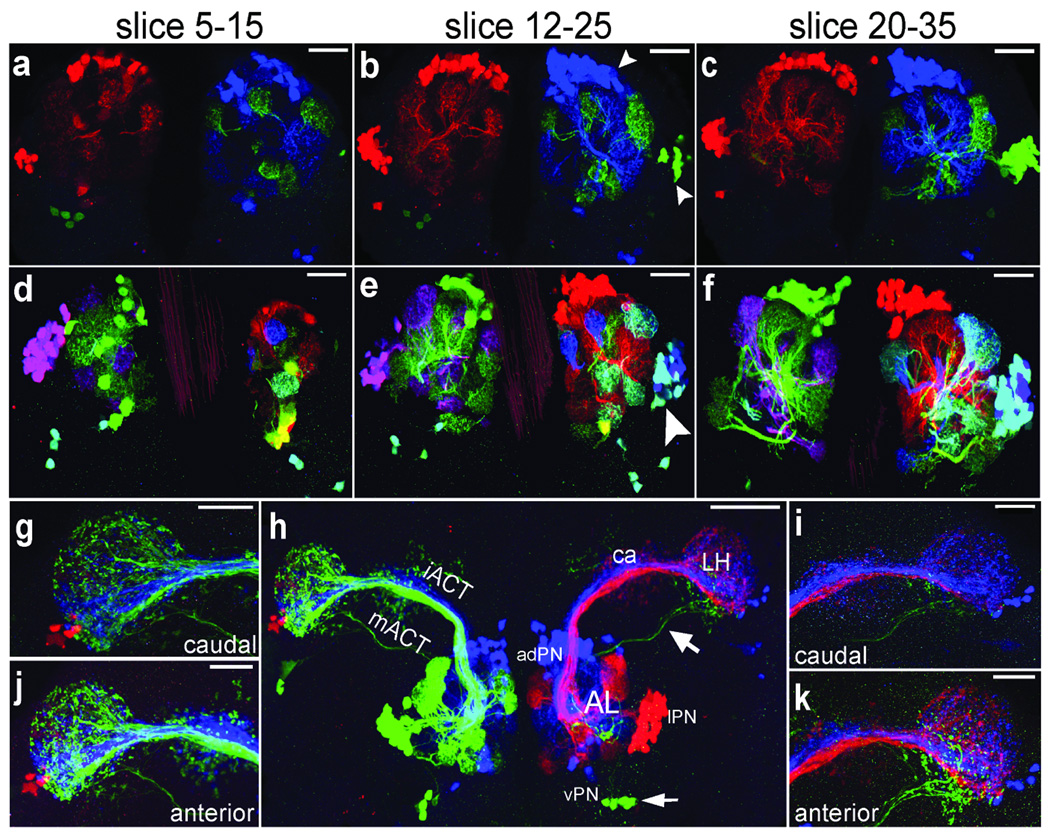

To validate dBrainbow, we chose the well-studied projection neurons of the olfactory system. The antennal lobe is the first processing region of the adult olfactory system and comprises distinct glomerular structures, each of which receives inputs from neurons carrying a specific olfactory receptor type; PNs innervate individual or combinations of glomeruli and send neurites to the mushroom body calyx (ca) and lateral horn (LH)10. MARCM and Flp-Out experiments showed that these PNs belong to distinct developmental lineages which partition the AL in a stereotyped and non-overlapping fashion11–14. The dBrainbow technique allows us to visualize the tiled PN patterns in single animals and makes this conclusion intuitive (Fig. 3a–f).

Figure 3. Expression of UAS-dBrainbow in three projection neuron lineages.

Single (a–c) and double (d–f) copies of UAS-dBrainbow were used along with hs-Cre; GH146-GAL4 to label the three PN lineages that express GH146-GAL4 (adPN, lPN, vPN), as well as the axon tracts (iACT, mACT) that connect the PN cell bodies to the LH (h) and ca (g,i–k). (a–f) show maximum intensity projection of several 1 µm confocal sections. Each PN lineage expresses a different fluorescent protein-epitope cassette and so appears in a different color. The arrowhead in (e) indicates the right lPN lineage in which recombination in the neuroblast occurred to select blue in one copy of UAS-dBrainbow but the recombinase did not act on the second copy until later to select green, so a subset of later-born neurons is labeled in cyan. (h) shows the antennal lobe and efferent neurons projecting to the lateral horn via the mACT and iACT; individual neurites can also be traced from the antennal lobe to the lateral horn via an alternative pathway (arrows). (g, i–k) show higher magnification views of the lateral horn from different orientations, where the lineage segregation is also apparent. Scale bars: 50 µm (a–f, k) and 20 µm (g,i–k).

GAL4 lines that target each lineage exclusively are not yet available for these PNs. GH146-GAL4, an enhancer trap inserted near Oaz, drives expression in a subset of PNs from three different lineages: anterior-dorsal (adPN), lateral (lPN) and ventral (vPN)14. hs-Cre; GH146-GAL4 flies were crossed to UAS-dBrainbow flies. The hs-Cre transgene is thought to be constitutively and ubiquitously expressed even in the absence of heat shock15, 16; dBrainbow recombination likely occurs in neuroblasts that give rise to daughter cells expressing the same fluorescent protein. Neurons within each lineage are labeled in the same color, which is ideal for studying the relationships between lineages. In approximately a third of our preparations, each lineage is labeled in a different color: the choice of color is random, independent, and approximately equal (Supplementary Table 3). The adPN and lPN lineages (Fig. 3b) project to distinct sets of glomeruli: there is no overlap between their neurites as shown by the lack of blue- green overlap. The vPN lineage (Fig. 3a), which has only six GH146-GAL4 positive cells, also has a distinct projection pattern. With dBrainbow color labeling, it is possible to visualize the way the different PN lineages tile the AL and also how their neurites subdivide the LH. The neurites from the adPN lineage remain segregated from those of the lPN lineage as they travel to the ca and LH (Fig. 3g–k), in agreement with published results11, 14, 17. Because of the bright labeling and unambiguous color assignment, we can also trace neural processes over long distances: single axons from vPN take an alternative route from the AL to the LH18 (Fig. 3h).

Two copies of dBrainbow increase the color palette

The PN lineages can be further subdivided by including a second copy of the UAS-dBrainbow transgene: this results in six colors (Fig. 1). The amplification of weak signal by antibody staining makes the presence of a given cassette unambiguous. The grey-scale photomultiplier signals from the individual red, green, and blue color channels established by different excitation laser/emission filter combinations are pseudocolored in red, green, and blue for single copy. With two copies, cyan (blue and green), magenta (red and blue), and yellow (green and red) are also possible (Fig. 3d–f). Usually a PN lineage is labeled with a single color, but sometimes the recombinase acts on one of the dBrainbow constructs partway through neuroblast divisions and a subset of the lineage is labeled in a different color, as is shown for the right lateral lineage (Fig. 3e): a subset of cyan (blue and green) lPN neurons are nested within a blue lPN lineage clone. This fortuitous temporal delay confers the ability to subdivide individual lineages and follow their processes in the context of their neighbors.

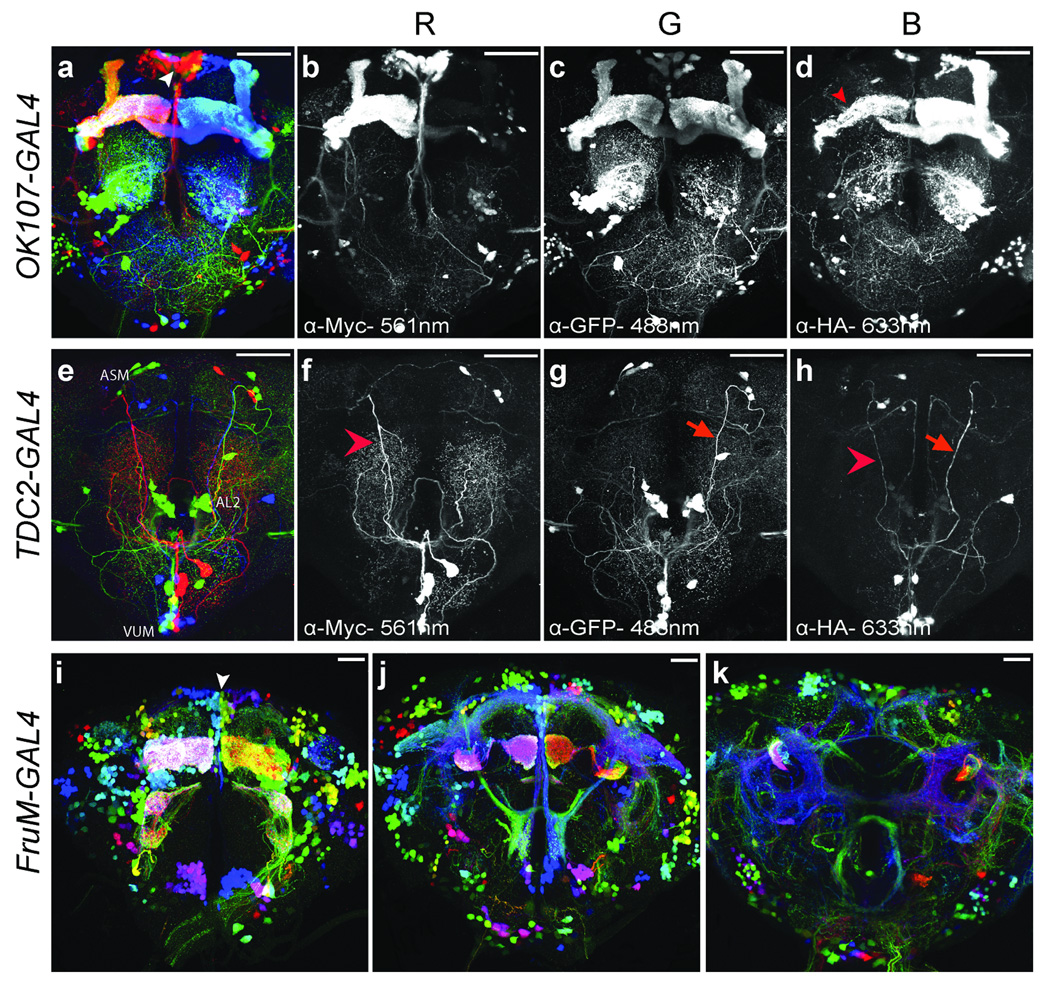

We used UAS-dBrainbow to subdivide the OK107-GAL4, Tdc2-GAL4, and FruM-GAL4 expression patterns (Fig. 4). OK107-GAL4 expresses in the mushroom bodies19, intrinsic interneurons of the AL, and many other neurons. dBrainbow labels the four neuroblasts that compose the mushroom bodies in different colors (Fig. 4a–d). Each neuroblast is capable of producing the three types of mushroom body neurons19; the time at which the recombination event occurred dictates what mixture of γ, α’ β’, or α β neurons are labeled in a given color. In some cases (5 of 40 examples) we see clones that label the γ lobes only (Fig. 4d). Since these are the first-born neurons, we suspect that the Cre recombinase may prevent neural proliferation or cause toxicity in later-born mushroom body neurons, as has previously been reported16. When hs-Cre; OK107-GAL4; UAS-dBrainbow flies were heat-shocked during development, mushroom body labeling was reduced (data not shown), presumably because more neurons are dying or failing to develop. To try to obtain a better mixture of colors within each lineage and reduce Cre toxicity, we identified additional sources of Cre recombinase: hs-Cre*20, hsp70-Cre21, and UAS-EBD-Cre16. Our results (Supplementary Figure 4 and data not shown) agree with the published assessment: all the Cre lines tested were both leaky and incompletely inducible. In OK107-GAL4, two lineages of AL intrinsic neurons are also labeled and appear to project to an overlapping set of glomeruli (Fig. 4a). Both OK107-GAL4 and FruM-GAL4 express in neurons of the pars intercerebralis (PI). This structure includes neurons that release neuropeptides such as Dilp and FMRF22. Because of the extensive color diversity here, our images demonstrate that the PI may include neurons from several different lineages (arrows in Fig. 4a and i).

Figure 4. dBrainbow labels lineages or individual neurons in different colors.

Maximum intensity projections of confocal stacks of OK107-GAL4 (a–d) and Tdc2-GAL4 (e–h) with UAS-dBrainbow and hs-Cre are shown as a three-color merged image and the grey-scale red, green, and blue channels labeled with the imaged wavelengths (blue is used to represent the AlexaFluor633). It is possible to trace individual VUM neurons over long distances ((f–h), arrowheads). (i–k) Three 35µm sub-stacks of hs-Cre; UAS-dBrainbow; UAS-dBrainbow, FruM-GAL4 divide the ~2000 neurons labeled by FruM-GAL4 into many subpopulations demarcated by different colors. Scale bars 50 µm.

Tracing individual neurons

Octopamine is a biogenic amine that modulates fly aggression, ovulation and appetitive learning23. There are ~100 broadly projecting octopaminergic neurons marked by Tdc2-GAL4 expression in the adult brain, which were divided into 27 neural cell types based on Flp-Out analysis9. One of the challenges of prior work was assigning individual cell clones from different specimens to a particular class. Neurons in the same class show variability in different animals24 and some classes have similar projection patterns. UAS-dBrainbow allows us to visualize several individual neurons simultaneously in the same preparation (Fig. 4e–h). With color labeling it is easier to distinguish the ipsilateral projections of the ventral paired median neurons (VPM) from bilateral projections of the ventral unpaired median neurons (VUMs), for example. The Flp-Out analysis proposed that there was a single VUM-3a neuron in each of the mandibular and maxillary clusters that had a very similar trajectory24; our results confirm this because we can see the two neurons in different colors in the same sample. Our images consistently label all cells in the AL2 cluster in a given hemisphere in the same color, suggesting that these neurons derive from the same lineage. Previous work showed that the VPMs and VUMs derive from distinct lineages24, but in our images the VUMs were always labeled in a mixture of colors, indicating that they may derive from several different lineages. It is possible to trace individual axons over long distances, but comparison between the Flp-Out clones (with membrane-targeted reporters) and our images suggests that small neurites are not filled as well by the cytoplasmic fluorescent proteins of dBrainbow.

The male-specific isoform of the Fruitless transcription factor (FruM) plays a critical role in establishing proper male courtship behavior. FruM expression is complex, including many cell types and more than 2000 cells25, 26. The pattern has been previously subdivided into clusters based on proximity of cell bodies27, but our images (Fig. 4i–k) show that these clusters are often subdivided by color and thus may include neurons from several different lineages and functional neural classes. Our lineage dissection of the FruM expression pattern with dBrainbow can now be compared to recent MARCM analysis28, 29.

Color labeling aids mapping from brain to periphery

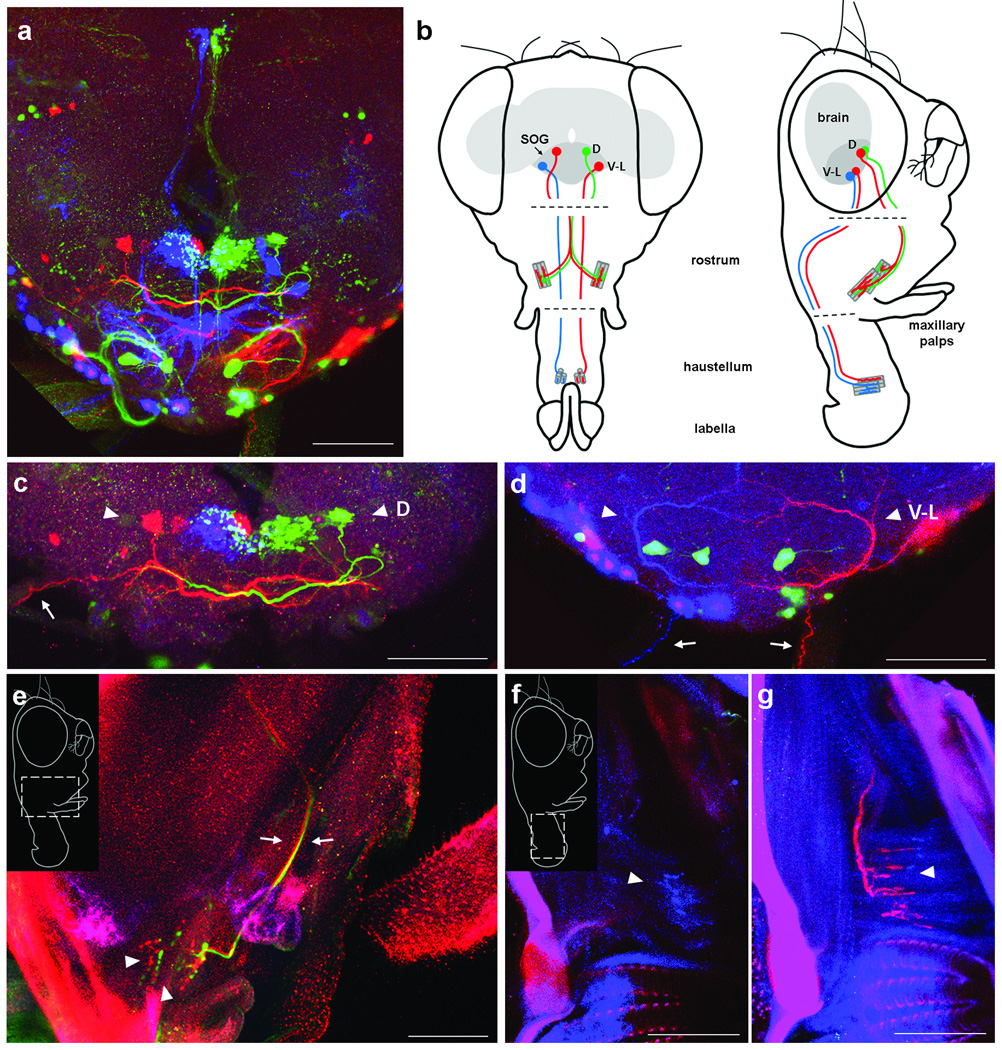

To demonstrate the power of dBrainbow for following individual neurons, we applied the technique to motor neurons controlling feeding behavior. The subesophageal ganglion (SOG) at the base of the brain receives gustatory inputs and sends motor outputs to mouthpart muscles. While taste inputs are relatively well studied (reviewed in30, 31), questions remain about the function of SOG motor neurons. Retrograde labeling experiments identified several SOG motor neurons innervating proboscis muscles32, but only two types of SOG motor neurons have been thoroughly described with GAL4 lines and confocal imaging33, 34. We analyzed R12D05-GAL4 (gift of G. Rubin) with dBrainbow to discover additional motor neurons within a pattern of other cells in the SOG and their muscle targets in the proboscis (Fig 5a).

Figure 5. dBrainbow expression in motor neurons that connect the subesophogeal ganglion to the proboscis muscles.

Expression of one copy of dBrainbow in the line R12D05-GAL4 in both brain and periphery of a single fly. (a) A cluster of several cell types in the SOG. Confocal stack imaged at 20×, maximum projection. (b) Frontal and lateral schematics of a fly head with proboscis extended, showing the brain in grey and the SOG in darker gray. Two motor neuron types (D and V-L pairs) are shown in color, projecting out to NMJs on their proboscis target muscles. The proboscis is dissected separately (dashed lines) to allow antibody penetration. (c) Confocal sub-stack showing the dorsal motor neurons (arrowheads D) labeled in red and green. These send axons out the pharyngeal nerve (visible at left for the red cell (arrow); the other nerve carrying the green axon is folded over at the front). Two clusters of neurites in the middle do not belong to these neurons, as they are labeled in blue and green rather than red and green. (e) Confocal sub-stack of the rostrum, lateral view, as shown in inset. The red and green axons travel through the proboscis together (arrows), to terminate at NMJs near the distal end of the rostrum (arrowheads). Both axons go to both sides of the rostrum (not shown). A maxillary palp can be seen at right. (Background is caused by autofluorescence of intact cuticle.) (d) Confocal sub-stack showing a pair of ventrolateral neurons with C-shaped arbors in the SOG in blue and red (arrowheads V-L). Their axons leave through the labial nerves at SOG bottom (arrows). (f,g) The blue and red axons terminate in NMJs on the transverse muscles in the distal end of the haustellum, near the labella. Sub-stacks at different levels show faint blue (f), and bright red (g) terminals. The dotted rows at the bottom of each image are cuticle autofluorescence of labellar pseudotracheae. At higher gain in g, autofluorescence in the blue channel also shows the muscle fibers of the haustellum: longitudinal muscles (vertical fibers in the image) and transverse muscles (horizontal). Scale bars: 50µm.

Because R12D05-GAL4 is relatively sparse and does not contain large lineages, one copy of dBrainbow was sufficient for us to identify samples in which the color combinations revealed specific cell types, such as the red-green pair of motor neurons in the dorsal SOG that extend axons ipsilaterally through the pharyngeal nerve and terminate in neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) at the distal end of the rostrum, possibly on muscle 335. (Fig. 5b,c,e). In 9 samples examined, the colors of these two dorsal SOG motor neurons always matched the colors at these NMJs (Supplementary Table 4). R12D05-GAL4 also labels a ventrolateral motor neuron pair (red and blue in Fig. 5b,d,f,g) that exits the SOG via the labial nerve. The C-shaped arbors resemble a motor neuron backfilled by Rajashekhar and Singh32, which they attributed to a longitudinal muscle in the haustellum (muscle 6). Our color matching NMJs are reproducibly located on the nearby transverse muscle 8, which is suspected to be involved in opening the labella for feeding35. It is possible that dBrainbow and three-dimensional confocal imaging will allow more definitive mapping of motor targets than the backfill technique. The two neuron pairs discussed above are the only motor neurons that reproducibly show NMJs in the proboscis in R12D05-GAL4. The distinctive arbors of the dorsal and ventrolateral motor neurons (Fig. 5b) were present in most brains examined; counts of these and other SOG cells labeled with UAS-dBrainbow in this GAL4 line are shown in Supplementary Table 4. The function of these motor neurons can now be addressed with the genetic access that this GAL4 line provides.

We thus find that dBrainbow can be used to follow arbors of individual neurons within a pattern that would be irresolvable if labeled with a single fluorescent protein. We further show that dBrainbow can label neurons from soma and dendrites all the way out through the periphery to NMJs. We believe this to be the first account of a GAL4 line targeting the proboscis motor neurons described here. Having a 3-dimensional image of a motor neuron controlling a particular muscle is an important step in understanding the anatomy of circuits underlying motor behaviors.

Discussion

The Drosophila Brainbow technique enables observation of the projections of many different neurons individually within their native context and allows interactions between lineages to be visualized in the same brain rather than relying on computational alignments of neurons or lineages from different preparations. The combination of neuronal targeting with sparse GAL4 lines and faithful color expression throughout neurites allows us to follow processes over long distances and even through discontinuous samples such as the brain and peripheral NMJ in the proboscis.

The dBrainbow construct can be used in two modes: for live imaging with two useable colors from endogenous fluorescence and for imaging fixed tissue with six colors derived from antibody-epitope combinations. To accomplish this, we expanded the repertoire of fluorescent proteins and epitope-antibody options usable in flies. Live imaging using endogenous fluorescence may be best suited to the more transparent embryonic or larval stages. New developments in bright, photostable blue and far-red fluorescent proteins should be incorporated.

The vertebrate Brainbow system was a huge leap forward in visualizing many individual neurons simultaneously; it allowed direct comparisons between similar neurons in their native context. dBrainbow adds two new innovations. Because the dBrainbow construct is under the control of a binary expression system, it can be targeted to neurons of interest using the extensive collections of available GAL4 lines. (The vertebrate Brainbow is currently fused to a single Thy1 promoter and so can only visualize neurons within the Thy1 expression pattern6.) Secondly, the use of epitopes and antibodies permits signal amplification and spectrally discrete, photostable fluorescent dyes. This makes color assignment and fine process tracing easier. Future versions may use membrane targeted proteins to improve neurite tracing. A synaptically localized version of dBrainbow would also have applications for circuit mapping. The UAS-dBrainbow construct can be used to anatomically subdivide complex GAL4 patterns and study individual neurons and lineages in context. We have focused entirely on the nervous system, but the construct could be used in other tissues.

The current version of dBrainbow works well for labeling neurons from the same lineage in a common color because of the early expression of the Cre recombinase in the neuroblasts. Biological questions remain about how lineages develop in relation to one another. The lineages may act as functional units within neural circuits; understanding how they project and interact is key for testing this hypothesis. Some GAL4 lines express in multiple lineages and dBrainbow represents an efficient way to image individual lineages within them. For labeling individual neurons, a GAL4 line that does not express throughout whole lineages can be chosen. Although the recombination to select a specific fluorescent protein occurs in the neuroblast, only the cells expressing GAL4 produce this color. To subdivide the neurons within a lineage into different colors would require a truly inducible source of Cre recombinase. All of the existing Drosophila melanogaster Cre reagents suffer from drawbacks – leaky expression, poor inducibility, and/or toxicity. The development of better Cre reagents would be a great contribution to the field. We routinely compare the total expression pattern of a GAL4 labeled with UAS-dBrainbow to the expression pattern revealed by cytoplasmic UAS-EGFP (Bloomington #1521; B. J. Dickson 1996 unpublished) or UAS-mCD8-GFP to determine what fraction of the neurons we are detecting and whether their projections appear normal. With appropriate controls, we have been able to obtain biologically interesting results with the existing hs-Cre lines.

One of the next major goals in Drosophilamelanogaster neuroanatomy is to map each individual neuron in the fly brain. Techniques such as dBrainbow facilitate this by speeding up imaging (multiple individual neurons can be seen in each brain), but also because labeling one neuron in the context of others makes assigning it to a class or type less ambiguous.

Methods

Molecular Biology and Drosophila Genetics

DNA encoding the Drosophila codon-optimized fluorescent proteins was ordered from DNA2.0. The fluorescent proteins were then cloned into shuttle vectors carrying cellular localization signals. Epitope tags36 were added on PCR primers synthesized by IDT. The vectors are modular so individual components can be exchanged by restriction digests. The final constructs were cloned into the PhiC31 integration vector JFRC-MUH37 for generating Drosophila melanogaster transformants at attp2 and attp4038 (Genetic Services, Inc.). The lox sites used were loxP, lox2272, and lox517115, 39. The constructs and DNA sequences have been deposited with AddGene. We built hs-Cre; enhancer-GAL4 stocks and crossed virgin females to UAS-dBrainbow males. The hs-Cre lines are from the Bloomington Stock Center (#766 and #851). This construct contains a mos1 enhancer element thought to drive ubiquitous, early expression15, 16. Unless noted, we reared fly crosses at 18°C and did not heat-shock. We saw no increase in sparseness of the color distribution with adult heat-shock. Heat shocks early in development caused toxicity rather than an increase in neuronal labeling. Additional fly stocks used were Fruitless GAL4 25, GH146-GAL440 (Bloomington #30026), TDC2-GAL4 41, OK107-GAL442, and R12D05-GAL4 (gift of G. Rubin).

Immunohistochemistry

Adult brain and ventral nerve cords were dissected with Inox 5 forceps on Sylgard dishes loosely following established protocols43. For endogenous fluorescence, 3–7 day old adult females were dissected in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed rotating at room temperature with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, P1213) for 1 hr. Samples were then washed 3× for 20 min each with PAT (1× PBS, 1% BSA (Sigma A-6793), and 0.5% Triton (Sigma X-100)). Tissue was rinsed in 1× PBS and then mounted in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, Inc. H-1000) on glass slides with two transparent reinforcement rings as spacers. Before imaging, mounted samples were kept at room temperature for 1 hr or stored at −20°C. For antibody staining, 3–7 day old female flies were dissected in 1× PBS. (For proboscis staining, the proboscis segments were cut into separate pieces to allow antibody penetration.) Tissue was fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, P1213) overnight (about 16hr) at 4°C with gentle rocking. Samples were washed 3× for 20 min each with PAT and then blocked with 3% normal goat serum (NGS; BioSource, PCN5000) in PAT for 1 hr at room temperature. Primary antibody incubations were performed overnight at 4°C, nutating in 500 µl PAT+NGS with the following dilutions: Rabbit anti-GFP (1:500; Invitrogen, A11122), Mouse anti-Myc (1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 9E10), and Rat-anti-HA (1:100; Roche, 11867423001). Samples were washed 3× for 20min each with PAT and then incubated overnight with goat secondary antibodies from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen44: AlexaFluor488 anti-Rabbit (1:500; A11034), AlexaFluor568 anti-Mouse (1:500; A11031), and AlexaFluor633 anti-Rat (1:500; A21094). Samples were washed again 3× for 20 min each with PAT, rinsed with 1× PBS, and mounted in VectaShield. Before imaging, mounted samples were kept at room temperature for 1 hr or stored −20°C. While the majority of the crosses were not heat-shocked, since hs-Cre provides enough baseline expression to generate recombination events, the R12D05-GAL4 crosses were heat-shocked for 1 hr at 37°C at 24hrs after egg-laying. We find that the cross-absorbed secondary antibodies and the Triton concentrations are critical for obtaining clean fluorescent signals with dBrainbow.

S2 Cell Culture

S2 cells were grown in Schneider's Drosophila melanogaster media containing heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 10 µg/ml penicillin and streptomycin, pelletted, and resuspended to a density of 1× 106 cells/ml in 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well). Each well was transfected with 1.25 µg of DNA purified with a QIAprepSpin Maxi Kit using the QIAGEN Effectene Transfection Kit. Ubiquitin-GAL4 was used to drive UAS-dBrainbow and different fluorescent protein constructs. For transfections of UAS-dBrainbow constructs 150 ng hs-Cre DNA was co-transfected in addition with 1 µg UAS-dBrainbow DNA and 100 ng Ubiquitin-GAL4 DNA. For each transfection we used 1 µg of fluorescent protein DNA, 100 ng Ubiquitin-GAL4 DNA and 150 ng of pcDNA3 to reach a total DNA concentration of 1.25 µg/well. The cells were then incubated for 2 days at 25°C and analyzed under a confocal microscope.

Confocal Imaging

Confocal images were taken on a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope (Zen 2009 software) using a 20× Plan-Apochromat 0.8NA lens with the following settings: 1 µm Z steps, sequential scanning, 1024×1024 frame size, 12bit data, scan speed 7, and bidirectional scanning with auto-Z correction. We also imaged endogenous fluorescence and antibody-stained samples with a 40× Plan-Apochromat 1.3NA oil immersion lens on a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope (Zen 2008 software) to improve the spectral separation using wavelength-specific meta-detectors. The critical step to achieve completely separate detection of each fluorescent protein or AlexaFluor dye was to scan sequentially: EBFP or Cerulean for the endogenous version was imaged first with the 458 nm Argon laser line and 470–500 nm band-pass filters, then mK02 or AlexaFluor568 with DPSS 561 nm line and 575–615 nm band-pass filter. Lastly, GFP or AlexaFluor488 was imaged with a 488nm Argon laser and 505–550 nm band-pass filter. For the antibody version, AlexaFluor633 was visualized with the HeNe 633 nm laser line and 650 nm long-pass filter. We carefully checked that there was no bleed-through with these settings when we imaged the constructs expressing each fluorescent protein individually. Original confocal image stacks are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Arnold, and Elise Shumsky and Alex Soell (Zeiss) for help with imaging and spectral separation. We thank B. Pfeiffer, A. Nern, and G. Rubin for sharing vectors and recombinase lines prior to publication and for the gift of R12D05-GAL4. We thank V. Hartenstein (UCLA), B. Gerber (U. Leipzig), and T. Lee, B. Baker, and P. Keller for helpful discussions about biological applications of dBrainbow. We thank S. Albin, A. Seeds, and E. Hoopfer for scientific discussion of the project and D. Grover for statistical advice. We thank K. Basler, R. Yagi, and C. Lehner (U. of Zurich) and M. Siegal (NYU) for additional Cre lines. All affiliations Janelia Farm Research Campus unless noted.

Footnotes

Author contributions

S.H. designed and performed cloning, tested constructs in S2 cells, and made the figures. P.C. performed the fly genetics, immunohistochemistry, and confocal imaging. C.M. generated and analyzed the SOG and proboscis data. D.H. generated the recombinant fly stocks. L.L.L. advised on selection of fluorescent proteins, construct design and the conversion from endogenous fluorescence to antibody. J.H.S. conceived the project, cloned initial test constructs, and wrote the paper with help from S.H., P.C., C.M., and L.L.L.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lichtman JW, Livet J, Sanes JR. A technicolour approach to the connectome. Nature reviews. 2008;9:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson JH. Mapping and manipulating neural circuits in the fly brain. Advances in genetics. 2009;65:79–143. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(09)65003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellen HJ, Tong C, Tsuda H. 100 years of Drosophila research and its impact on vertebrate neuroscience: a history lesson for the future. Nature reviews. 2010;11:514–522. doi: 10.1038/nrn2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai SL, Lee T. Genetic mosaic with dual binary transcriptional systems in Drosophila. Nature neuroscience. 2006;9:703–709. doi: 10.1038/nn1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu HH, Chen CH, Shi L, Huang Y, Lee T. Twin-spot MARCM to reveal the developmental origin and identity of neurons. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:947–953. doi: 10.1038/nn.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livet J, et al. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature. 2007;450:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaue-Sawano A, et al. Visualizing spatiotemporal dynamics of multicellular cell-cycle progression. Cell. 2008;132:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ai HW, Shaner NC, Cheng Z, Tsien RY, Campbell RE. Exploration of new chromophore structures leads to the identification of improved blue fluorescent proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5904–5910. doi: 10.1021/bi700199g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch S, Selcho M, Ito K, Tanimoto H. A map of octopaminergic neurons in the Drosophila brain. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2009;513:643–667. doi: 10.1002/cne.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masse NY, Turner GC, Jefferis GS. Olfactory information processing in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R700–R713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferis GS, Marin EC, Stocker RF, Luo L. Target neuron prespecification in the olfactory map of Drosophila. Nature. 2001;414:204–208. doi: 10.1038/35102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marin EC, Jefferis GS, Komiyama T, Zhu H, Luo L. Representation of the glomerular olfactory map in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2002;109:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong AM, Wang JW, Axel R. Spatial representation of the glomerular map in the Drosophila protocerebrum. Cell. 2002;109:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai SL, Awasaki T, Ito K, Lee T. Clonal analysis of Drosophila antennal lobe neurons: diverse neuronal architectures in the lateral neuroblast lineage. Development (Cambridge, England) 2008;135:2883–2893. doi: 10.1242/dev.024380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegal ML, Hartl DL. Transgene Coplacement and high efficiency site-specific recombination with the Cre/loxP system in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:715–726. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidmann D, Lehner CF. Reduction of Cre recombinase toxicity in proliferating Drosophila cells by estrogen-dependent activity regulation. Development genes and evolution. 2001;211:458–465. doi: 10.1007/s004270100167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jefferis GS, et al. Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell. 2007;128:1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito K, Awasaki T. In: Brain Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Technau GM, editor. Vol. 628. Austin: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science and Business Media; 2008. pp. 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee T, Lee A, Luo L. Development of the Drosophila mushroom bodies: sequential generation of three distinct types of neurons from a neuroblast. Development (Cambridge, England) 1999;126:4065–4076. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.18.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegal ML, Hartl DL. Application of Cre/loxP in Drosophila. Site-specific recombination and transgene coplacement. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J. 2000;136:487–495. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-065-9:487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yagi R, Mayer F, Basler K. Refined LexA transactivators and their use in combination with the Drosophila Gal4 system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:16166–16171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005957107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Velasco B, et al. Specification and development of the pars intercerebralis and pars lateralis, neuroendocrine command centers in the Drosophila brain. Developmental biology. 2007;302:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potter CJ, Luo L. Octopamine fuels fighting flies. Nature neuroscience. 2008;11:989–990. doi: 10.1038/nn0908-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busch S, Tanimoto H. Cellular configuration of single octopamine neurons in Drosophila. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2010;518:2355–2364. doi: 10.1002/cne.22337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manoli DS, et al. Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature. 2005;436:395–400. doi: 10.1038/nature03859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demir E, Dickson BJ. fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimura K, Hachiya T, Koganezawa M, Tazawa T, Yamamoto D. Fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron. 2008;59:759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cachero S, Ostrovsky AD, Yu JY, Dickson BJ, Jefferis GS. Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu JY, Kanai MI, Demir E, Jefferis GS, Dickson BJ. Cellular organization of the neural circuit that drives Drosophila courtship behavior. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1602–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isono K, Morita H. Molecular and cellular designs of insect taste receptor system. Front Cell Neurosci. 2010;4:20. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2010.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vosshall LB, Stocker RF. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Annual review of neuroscience. 2007;30:505–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajashekhar KP, Singh RN. Neuroarchitecture of the tritocerebrum of Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1994;349:633–645. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tissot M, Gendre N, Stocker RF. Drosophila P[Gal4] lines reveal that motor neurons involved in feeding persist through metamorphosis. Journal of neurobiology. 1998;37:237–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon MD, Scott K. Motor Control in a Drosophila Taste Circuit. Neuron. 2009;61:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller A. In: Biology of Drosophila. Demerec M, editor. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1950. pp. 420–534. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brizzard B. Epitope tagging. BioTechniques. 2008;44:693–695. doi: 10.2144/000112841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeiffer BD, et al. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groth AC, Fish M, Nusse R, Calos MP. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics. 2004;166:1775–1782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodin S, Georgiev P. Handling three regulatory elements in one transgene: combined use of cre-lox, FLP-FRT, and I-Scel recombination systems. BioTechniques. 2005;39:871–876. doi: 10.2144/000112031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stocker RF, Heimbeck G, Gendre N, de Belle JS. Neuroblast ablation in Drosophila P[GAL4] lines reveals origins of olfactory interneurons. Journal of neurobiology. 1997;32:443–456. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199705)32:5<443::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole SH, et al. Two functional but noncomplementing Drosophila tyrosine decarboxylase genes: distinct roles for neural tyramine and octopamine in female fertility. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14948–14955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connolly JB, et al. Associative learning disrupted by impaired Gs signaling in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Science (New York, N.Y. 1996;274:2104–2107. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu JS, Luo L. A protocol for dissecting Drosophila melanogaster brains for live imaging or immunostaining. Nature protocols. 2006;1(No. 4):2110–2114. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panchuk-Voloshina N, et al. Alexa dyes, a series of new fluorescent dyes that yield exceptionally bright, photostable conjugates. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1179–1188. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizzo MA, Springer GH, Granada B, Piston DW. An improved cyan fluorescent protein variant useful for FRET. Nature biotechnology. 2004;22:445–449. doi: 10.1038/nbt945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang G, Gurtu V, Kain SR. An enhanced green fluorescent protein allows sensitive detection of gene transfer in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:707–711. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai T, et al. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nature biotechnology. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin MZ, et al. Autofluorescent proteins with excitation in the optical window for intravital imaging in mammals. Chemistry & biology. 2009;16:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaner NC, et al. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nature biotechnology. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shcherbo D, et al. Far-red fluorescent tags for protein imaging in living tissues. Biochem J. 2009;418:567–574. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Jackson WC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. Evolution of new nonantibody proteins via iterative somatic hypermutation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:16745–16749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407752101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.