Abstract

Objectives

Previous studies have identified behavioral phenotypes that predispose genetically vulnerable youth to a later onset of bipolar I or II disorder, but few studies have examined whether early psychosocial intervention can reduce risk of syndromal conversion. In a one-year open trial, we tested a version of family-focused treatment adapted for youth at high risk for bipolar disorder (FFT-HR).

Methods

A referred sample of 13 children (mean 13.4 ± 2.69 years; 4 boys, 9 girls) who had a parent with bipolar I or II disorder participated at one of two outpatient specialty clinics. Youth met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder (n = 8), cyclothymic disorder (n = 1), or bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (n = 4), with active mood symptoms in the past month. Participants were offered FFT-HR (12 sessions in four months) with their parents, plus psychotropic medications as needed. Independent evaluators assessed depressive symptoms, hypomanic symptoms, and global functioning at baseline and then every four months for one year, with retrospective severity and impairment ratings made for each week of the follow-up interval.

Results

Families were mostly adherent to the treatment protocol (85% retention), and therapists administered the FFT-HR manual with high levels of fidelity. Youth showed significant improvements in depression, hypomania, and psychosocial functioning scores on the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. They also showed significant improvements in Young Mania Rating Scale and Children’s Depression Rating Scale scores.

Conclusions

FFT-HR is a promising intervention for youth at high risk for BD. Larger-scale randomized trials that follow youth into young adulthood will be necessary to determine whether early psychosocial intervention can reduce the probability of developing bipolar I or II disorder among genetically vulnerable youth.

Keywords: early intervention, family therapy, high risk, pediatric, prevention, psychoeducation

Between 50–66% of adult patients with bipolar disorder (BD) report onset of their disease prior to 18 years, and 15–28% report onset before age 13 (1). BD in childhood or adolescence exhibits a more severe, protracted, and continuously cycling course compared to adult-onset BD, often with mixed episodes, longer episode durations, psychosis, and multiple comorbidities (2). Many of these features also characterize prodromal forms of the illness, which can be identified in childhood or early adolescence (3, 4).

Several research groups have identified the phenotype that may be most likely to predispose youth to the later development of bipolar illness. Birmaher et al. (3) found that youth (mean age 7–17 years) who met research criteria for BD not otherwise specified (NOS)—operationalized by multiple short periods of mania that do not meet the DSM-IV episode duration thresholds or symptom count criteria—are at substantially elevated risk for ‘converting’ to bipolar I disorder (BD-I) or bipolar II disorder (BD-II). When stratifying by family history of BD-I or BD-II, the risk of conversion in youth presenting with the BD-NOS phenotype was 51% over four years, compared to 30% among BD-NOS patients with no family history of BD.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and cyclothymic disorder also occur disproportionately in children who later develop BD. Geller et al. (5) found that 33% of children (mean age = 10.3 years) with prepubertal-onset MDD developed BD-I by a 10-year follow-up, compared to none of a group of matched healthy controls. Strober and Carlson (6) found that 20% of adolescents with MDD developed BD-I over 3–4 years, especially if they had a positive family history of BD, rapid symptom onset, and psychosis. A two-year prospective study in France found that among 80 youth (age 7–17 years) with MDD, 35 (43%) converted to BD-I or BD-II (7). In that same study, children with cyclothymic presentations were highly likely (64%) to experience at least one full-blown hypomanic or manic episode within two years, as compared to only 15% without cyclothymic presentations (7).

Given the observed trajectories of early-onset forms of bipolar spectrum disorder, it is reasonable to assert that without early intervention, the social and emotional development of high-risk youth may be seriously compromised. Accordingly, interventions designed to reduce affective morbidity and functional impairment in the high-risk period may prevent the progression to full BD-I or BD-II and have a dramatic, favorable impact on individual suffering.

Pharmacological treatments for the prodrome of BD are few and have not produced conclusive results (8–10). Psychosocial interventions, particularly those involving psychoeducation and skill training, may provide a treatment alternative for children at risk for BD, especially in cases where the youth decline medications or experience significant side effects. Several studies indicate that family-focused therapy (FFT) and multifamily psychoeducation groups are effective in alleviating mood symptoms, preventing recurrences, and enhancing psychosocial functioning among adult (11, 12), adolescent (13), and child BD patients (14, 15). Recent studies also suggest that youth at high risk for bipolar spectrum disorders—including those with depressive spectrum disorders with transient manic symptoms or severe emotional dysregulation—benefit from targeted psychoeducational therapy or behavior modification approaches (14, 16, 17). Notably, Nadkarni and Fristad (17) found that multifamily psychoeducation groups exert a protective effect on conversion to bipolar spectrum disorders among children with depressive spectrum disorders.

Using an open-trial design, the current study tested whether a brief (four-month), modified version of FFT (i) was acceptable to youth and families, (ii) was associated with high treatment adherence and competence by clinicians at two study sites, and (iii) promoted symptom stabilization and enhanced functioning over one year among high-risk youth. The FFT was designed to reduce stress, conflict, and affective arousal among youth and family members through enhancing knowledge about emotional regulation strategies, effective communication skills, and strategies for solving and implementing solutions to family problems.

Materials and methods

Participants

Children between the ages of 9 years, 0 months and 17 years, 11 months were recruited at Stanford University and the University of Colorado to participate in a one-year open trial of FFT adapted for youth at high risk for BD (FFT-HR), conducted between 1 September 2007 and 31 August 2008. Referrals originated from community practitioners, parent support groups, primary care doctors, and inpatient settings. After receiving a description of the study procedures, all participating children and parents read and signed University IRB-approved assent and consent forms.

Eligibility criteria for the youth were as follows: (i) English speaking; (ii) at least one biological parent with BD-I or BD-II according to the DSM-IV-TR (18); (iii) meeting DSM-IV criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of BD-NOS, MDD, or cyclothymic disorder. Diagnosis of the biological parent was confirmed by direct interview using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (19). The parent’s diagnosis did not have to be active or treated. BD-NOS required a distinct period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood plus two (three, if irritable only) DSM-IV symptoms of mania that caused a change in functioning, lasted for at least four hours in a day, and were present for a total of at least four days in the child’s lifetime, even if the days were not consecutive (3). Cyclothymia required at least one year with numerous periods of both hypomanic symptoms and depressive symptoms that did not meet full MDD or mania criteria. If the main diagnosis was MDD, the youth must have had a full DSM-IV depressive episode within the previous two years (20). Lastly (iv), the youth had to have significant affective symptoms as determined by a current Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (21) score > 11 or a current Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) (22) score >29.

Controversy surrounds the use of the BD-NOS category and its relation to BD-I and BD- II (2–4). Youth who meet the operational criteria for BD-NOS show levels of functional impairment comparable to youth with BD-I and BD-II (4). When they also have a parent with BD, they are at substantially heightened risk for developing BD-I or BD-II (3). Thus, youth with BD-NOS are an appropriate population with whom to investigate an early intervention program focused on the prevention of syndromal conversion.

Diagnostic evaluation

Children’s diagnoses were evaluated using the Washington University version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for Children (WASH-U-KSADS) (23) and the KSADS-Present and Lifetime Version (KSADS-PL) non-mood supplements (24, 25). The time frame of the WASH-U-KSADS and KSADS-PL was lifetime, with current episode ratings based on the worst 1–2 weeks in the prior four months. Both sites had master’s-level social workers, clinical psychologists, or child psychiatrists who were trained and reliable in administering the KSADS, MINI, YMRS, CDRS-R, and the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation [A-LIFE (26); see below]. At each site, board-certified psychiatrists conducted separate diagnostic evaluations with the youth and parents; final diagnoses were based on a consensus among all sources of information. Inter-rater reliability on the WASH-U-KSADS at Stanford was consistently κ > 0.90 at the item level. Reliability among 11 Colorado raters for KSADS depression items was 0.89 and for mania items 0.97. Cross-site reliability between diagnosticians at Colorado and Stanford for symptom presence/absence was 94% for KSADS depression items and 91% for mania/hypomania items.

Longitudinal assessment protocol

All follow-up interviews were conducted by an independent evaluator (IE) who was not involved in the patient’s treatment. The A-LIFE, the primary outcome instrument, is a semistructured interview that yields psychiatric status ratings (PSRs) on 0–6 scales for each week of a follow-up period and covers the severity of mania, hypomania, MDD, patterns of cycling, and evidence of significant departures from baseline mood states. The IE started by rating retrospectively each of the 16 weeks prior to the initial evaluation, and then rating prospectively each week of follow-up, based on separate interviews of the youth and parents every four months post-baseline. A weekly 1–7 rating of global functioning was also obtained from the A-LIFE Psychosocial Schedule at baseline (covering the prior 16 weeks) and every four months thereafter.

Secondary outcome instruments administered at baseline and every four months during the study year included the YMRS, an 11-item parent and child interview. Severity of YMRS items range from 0–4 or 0–8, and the maximum attainable score is 60. The clinician-rated CDRS-R, which assesses the presence and severity of 17 depressive symptoms, consists of a brief interview administered to parents and children separately, with consensus ratings based on both sources of information. The YMRS covered symptoms over the previous week and the CDRS the previous two weeks. Finally, at each research follow-up visit, parents filled out the Beck Depression Inventory-II (27) regarding their own mood states over the past two weeks.

Structure of FFT-HR

The modified FFT-HR consisted of 12 sessions over four months (8 weekly, 4 biweekly). During the remainder of the study year, the clinician could offer monthly booster sessions to help the family solidify new coping skills. The objectives of FFT-HR are to assist high-risk youth and their family members (i.e., parents, siblings) in: (i) recognizing the prodromal symptoms of depressive or manic/hypomanic episodes; (ii) distinguishing significant mood dysregulation from developmentally appropriate emotional reactivity; (iii) identifying stress-related triggers of mood swings; (iv) enhancing family communication and problem solving; and (v) developing prevention plans to avert mood escalations or deteriorations. In each FFT-HR module there are opportunities for youth and family members to learn behavioral strategies to modulate affective intensity and duration, especially when feeling provoked by other family members. In this manner, the treatment attempts to address the negative interactional patterns often associated with home environments with high expressed emotion (EE)—i.e., highly critical, hostile, or overprotective (28).

Psychoeducation (Sessions 1–4)

The first two sessions of psychoeduction acquaint the proband and family with the goals of FFT-HR and the signs and symptoms of mood disorders. The treatment objectives are described as: improving the child’s ability to regulate emotions, enhancing day-to-day functioning, and improving the emotional climate of the family. The youth is asked to describe his or her experiences with depression or, if relevant, hypomanic symptoms or comorbid disorders, whereas parents or siblings share their perceptions of how the youth’s mood or behavioral changes have affected the family. The parent with BD is asked to explain to the child, to the extent that he or she is comfortable, the nature of BD and how the parent has come to terms with his or her own diagnosis.

In session 3, the participants identify stressors currently affecting the youth, such as negative family interactions and peer or romantic relational conflicts. Youth are encouraged to monitor their daily moods and sleep/wake rhythms using a daily mood chart. Clinicians explain the nature of risk factors (e.g., alcohol or drug usage, provocative interpersonal interactions) and protective factors (e.g., regular sleep rhythms, effective family communication).

In session 4, the family develops a “mood management plan” to list medical and behavioral strategies to implement if the child’s mood, sleep, or thinking patterns start to change. The plan typically involves reducing interpersonal stress at home, stabilizing sleep rhythms, and, where appropriate, adjusting medications. Emotion regulation skills, to be initiated when participants identify the first signs of negative emotional arousal in themselves or others, may include relaxation or mindfulness exercises, distraction, or adaptive self-talk.

Communication enhancement training (Sessions 5–8)

Communication enhancement training is guided by the assumption that aversive communication and high EE reflect distress within the family in its attempts to cope with mood disorder in one or more family members (29). During this module, families become acquainted with four skills: expressing positive feelings, active listening, making positive requests for change, and expressing negative feelings. Through role-play/skills training exercises and between-session homework, participants learn to (i) ‘down-regulate’ impulsive expressions of negative emotions through pausing and putting difficult feelings into words; (ii) communicate in a manner that does not trigger or exacerbate emotional dysregulation in others; and (iii) shift attention from negative or destructive emotions to more conciliatory emotional states.

Problem-solving skills training (Sessions 9–12)

Problem-solving skills training is used to encourage families to identify difficult problems, break down large problems (e.g., “we don’t get along”) into smaller ones (“we need to lower our tones of voice”), generate lists of solutions and evaluate the pros and cons of each, and choose one or more solutions to implement (e.g., “alert each other when voice tones are becoming aggressive”). Topics often addressed in problem solving include difficulties getting along with siblings, chaotic sleeping or eating habits, adapting to family routines, and controlling irritable outbursts.

Youth with or at risk for early-onset BD often have mood or behavior problems that interfere with their ability to solve interpersonal problems (30). Problem solving allows the child and family members to express emotionally charged information within a structured context and to manage familial conflicts with adaptive self-talk, distraction, or negotiation techniques in place of shouting, hurling insults, or becoming assaultive.

Modification of the FFT-HR manual for younger children

We modified the FFT treatment for children between 9 and 12 years, including using simplified handouts that emphasized visual stimuli (e.g., mood charts with facial images portraying emotional states), flipcharts to explain key concepts, and flexible session structures. Parents played more active roles in directing younger children during in-session role-playing tasks or weekly homework assignments, whereas adolescents were given more autonomy in these tasks.

Data analyses

Statistical analyses tested a specific hypothesis: high-risk youth undergoing the 12-session course of FFT-HR would show reductions in mood symptom severity over one year. We used mixed-effects regression modeling with random slope/random intercept assumptions (31) to assess within-group changes in the primary outcome variables (A-LIFE weekly PSR ratings for depression and hypomania) and secondary outcome variables (CDRS-R and YMRS ratings made every four months, A-LIFE weekly functioning ratings) as a function of time. All longitudinal analyses were conducted by intent-to-treat. Assuming a one-year follow-up, the sample size of 13 had power of 0.76 to detect a large effect (i.e., R2 = 0.40) for changes in symptom scores (alpha = 0.05).

Results

Sample composition

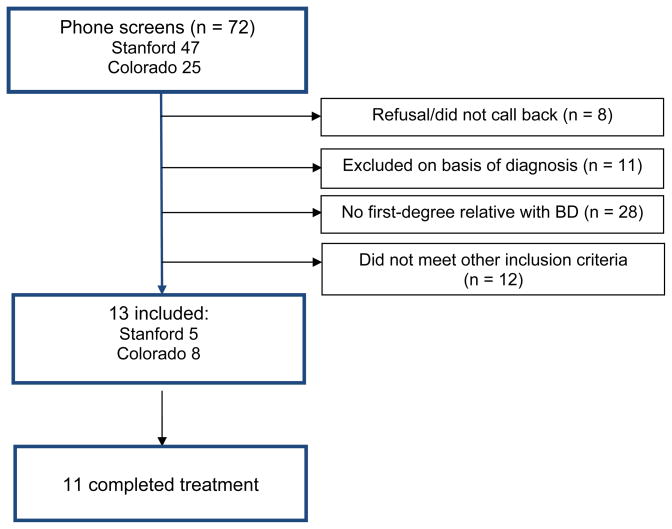

The 13 patients recruited for this study were drawn from 72 referrals to the Stanford (n = 47) and Colorado (n = 25) sites (see Fig. 1). The Stanford site was simultaneously recruiting for another study of children of BD parents with or without active symptoms, and thus obtained more referrals than the Colorado site. The most frequent reason for ineligibility at both sites was that neither of the youth’s parents, upon evaluation with the MINI, met DSM-IV criteria for BD-I or BD-II (n = 28).

Figure.

CONSORT diagram. BD = bipolar disorder.

The 13 youth (8 Colorado, 5 Stanford) ranged in age from 9 to 16 years (mean 13.4 ± 2.69); 4 (30.8%) were boys and 9 (69.2%) were girls. Eleven youth were Caucasian and 2 were of Hispanic ethnicity; one was of mixed race. Of the 13, 7 (5 with MDD, 2 with BD-NOS) had had a major depressive episode lasting at least two weeks within the four months prior to study entry (Table 1). All participants were actively symptomatic at study entry; the mean YMRS score for the sample was 13.88 ± 7.65 and the mean CDRS-R score was 39.36 ± 8.58. Of the 13, 9 scored ≥ 12 on the YMRS and 12 scored ≥ 29 on the CDRS, indicating clinically significant symptoms of (hypo)mania and depression, respectively. None met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for a manic or mixed episode at study entry.

Table 1.

Child and family characteristics

| Child diagnoses | |

| Major depressive disorder | 8 (61.5) |

| Cyclothymic disorder | 1 (7.7) |

| Bipolar disorder NOS | 4 (30.8) |

| Parent diagnoses | |

| Biological mother with BD-I | 6 (46.2) |

| Biological mother with BD-II | 1 (7.7) |

| Biological father with BD-I | 2 (15.4) |

| Biological father with BD-II | 4 (30.8) |

| Youth lives with | |

| Both biological parents | 8 (61.5) |

| Both biological parents in separate households | 2 (15.4) |

| Biological mother only | 1 (7.7) |

| Biological father only | 1 (7.7) |

| Biological mother and partner | 1 (7.7) |

Values are presented as n (%). NOS = not otherwise specified; BD-I = bipolar I disorder; BD-II = bipolar II disorder.

The parent with BD and any other parent who lived with the child were invited to participate in FFT-HR sessions, and all but two parents agreed. In all but one of the families, a healthy co-parent also participated; in a single case, the child participated with his mother with BD-I only. Beck Depression Inventory-II scores among parents at entry into the four-month FFT-HR protocol averaged 11.8 ± 9.7, indicating low levels of depression but with considerable range (from 2 to 37).

Therapy adherence

Families attended a mean of 11.85 ± 5.18 (range 0–19) FFT-HR sessions. One family never appeared for the first session, and one had only 3 sessions; the remainder (n = 11) attended 9 or more sessions. Two cases—both with fathers with BD (one with BD-I, one with BD-II)—were classified as study withdrawals (15%) and 11 were classified as completers (85% retention). All 13 families were offered monthly ‘booster’ sessions after the 12-session protocol, and 8 attended. Two families attended one extra session, 5 attended 2–4 booster sessions, and one attended 7 booster sessions. The mean duration of research follow-up from study entry to study exit was 53.7 ± 30.5 weeks.

Participants were permitted to continue with their individual therapy if they were enrolled in such treatment prior to the study. Of the 13 cases, 3 (23.1%) opted to continue in individual therapy during the four-month FFT protocol.

Youth attended a mean of 3.69 ± 4.29 (range 0–15) pharmacological management sessions during the year. They entered the study on a variety of medication regimens, and in most cases the study psychiatrists did not significantly alter these regimens during the course of the study. Of 8 participants with MDD: 1 was treated with an antidepressant only, 2 with atypical antipsychotics, 1 with lamotrigine, and 1 with the combination of lithium, an antidepressant, and a typical antipsychotic; 3 were not taking any medications. Of the 4 youth with BD-NOS: 2 were treated with stimulants alone, 1 with an antidepressant alone, and 1 with the combination of lithium, valproate, quetiapine, and an antidepressant. The single youth with cyclothymic disorder was treated with a psychostimulant and an antidepressant.

Therapist training and fidelity

Two expert trainers (DJM, ELG) conducted an eight-hour seminar at a study launch meeting to familiarize new clinicians with the FFT-HR manual and provided monthly group supervision sessions for the remainder of the trial. Independent raters assessed fidelity to the FFT-HR manual using the Treatment Competence and Adherence Scale, Revised (TCAS-R) (11, 32), which includes 13 adherence/skill items rated from 1 (poor) to 7 (excellent), followed by 27 items (rated from 0–3) measuring specific treatment strategies, therapeutic style, nonspecific factors, and proscribed techniques. The clinicians from Stanford and Colorado did not differ in overall adherence/competence ratings (range 1–7) measured throughout the study (Colorado, mean = 6.2 ± 1.2; Stanford, mean = 5.6 ± 1.5; p > 0.10; 39 ratings). In cases where overall adherence ratings fell below threshold (i.e., ≤ 4 on the 7-point scale), extra supervision was given to help ensure skillful application of the manual.

Clinical outcomes

Youth showed substantial improvements in depression PSR scores [time effect, F(1,799) = 315.62, p < 0.0001; Cohen’s d = 1.77, SE = 0.46] and modest improvements in hypomania PSR scores [time effect, F(1,795) = 21.10, p < 0.0001; d = 0.51, SE = 0.40; Table 2]. When the effects of medications (no mood stabilizers or antidepressants, n = 5; taking one or more of these, n = 8) were covaried, there was still significant improvement in depression scores [F(1,798) = 315.54, p < 0.0001] and hypomania scores [F(1,795) = 21.26, p < 0.0001] over the study year. There were no independent effects of medication status on depression or mania PSR scores or any effects of age in these models (all p > 0.10).

Table 2.

Symptom scores at baseline and 4, 8, and 12 months post-baseline

| Measure | Baseline | 4 months | 8 months | 12 months | Cohen’s d (SE) | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression PSR score (A- LIFE) | 3.95 (1.16) | 2.87 (1.17) | 1.87 (1.15) | 2.04 (0.99) | 1.76 (0.46) | 0.82–2.61 | 0.0001 |

| Hypomania score (A-LIFE) | 1.62 (0.88) | 1.38 (0.82) | 1.40 (0.84) | 1.26 (0.49) | 0.51 (0.40) | −0.29–1.27 | 0.0001 |

| CDRS-R | 39.36 (8.58) | 36.80 (5.45) | 28.22 (4.49) | 32.89 (11.63) | 0.63 (0.40) | −0.17–1.40 | 0.013 |

| YMRS | 13.88 (7.65) | 13.30 (10.05) | 9.67 (7.47) | 6.22 (5.52) | 1.15 (0.42) | 0.29–1.94 | 0.001 |

| Global functioning (A-LIFE) | 3.60 (1.17) | 2.92 (0.89) | 2.45 (1.33) | 2.02 (1.05) | 1.42 (0.44) | 0.52–2.23 | 0.0001 |

Scores are presented as mean (SD). CI = confidence interval; PSR = psychiatric status rating; A-LIFE = Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation; CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale.

Of the 11 cases with one-year follow-up data, 9 changed from A-LIFE PSR depression scores of 5 (severe; n = 7) or 6 (extremely severe; n = 2) to scores of 3 (moderate; n = 4), 2 (mild; n = 1) or 1 (asymptomatic; n = 4) by the year’s end. Two participants began with moderately severe depression (ratings of 4) and were moderately or mildly depressed by year’s end.

Participants showed moderate improvement on the CDRS-R from baseline to 12 months [F(1,40) = 6.73, p = 0.013; d = 0.63, SE = 0.40] and more significant improvement on the YMRS [F(1,33) = 12.98, p < 0.001; d = 1.15, SE = 0.42; Table 2]. At baseline, 9 of 13 participants (69.2%) scored ≥ 12 on the YMRS, whereas only 1 of 11 (9.1%) was above this clinical threshold at one year. Finally, youth showed significant improvements in weekly global functioning ratings on the A-LIFE [F(1, 141) = 28.05, p < 0.0001; d = 1.42, SE = 0.44]. There were no effects of age on CDRS-R, YMRS, or global functioning scores (all p > 0.10).

Of the 13 youth, only 1 with a diagnosis of BD-NOS developed a manic episode during the one-year interval. This child, who entered the study during a major depressive episode, became ill at week 22 of the follow-up and remained ill for 11 weeks. This rate of conversion to BD-I or BD-II (25%) among BD-NOS youth with a parent with BD is comparable to the one-year conversion rate of 26.6% among BD-NOS/positive family history youth in the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Illness in Youth study (3). Additionally, 2 participants (15.4%) had recurrences of major depression after recovering from the major depressive episode that had brought them into the study. One had an eight-week episode starting at 28 weeks and the other a two-week episode starting at 50 weeks.

Discussion

This article described a one-year treatment development trial of an adapted version of FFT for youth who were at high risk of developing BD-I or BD-II. The results suggest that FFT-HR is feasible to administer in this population and associated with a high rate of treatment retention (85%). Clinicians at both study sites showed high levels of fidelity to the treatment manual. Moreover, youth who participated in FFT-HR showed significant reductions in depression and hypomania symptoms and improvements in global functioning over one year.

Family psychoeducation may augment individual and family coping skills and protect high-risk youth from family stress or other life stressors that would otherwise contribute to their overall vulnerability to disease onset. Youth with adverse parent-child relationships are vulnerable to more severe depressions when under chronic stress than are youth with healthier parent-child relationships (33). The skill-training modules of FFT attempt to ameliorate the impact of high-EE attitudes and behaviors in families, including aversive communication between parent and offspring, hostility, low family cohesion and adaptability, and difficulties with conflict resolution (28). Family psychoeducation has been shown to improve similar dimensions of family behavior among adults with mood disorders (29).

Because the primary goals of this study were to determine the feasibility and acceptability of FFT-HR, it was designed as an open trial with no randomized control. Thus, it was not designed to address whether family treatment is necessary to bring about symptom reductions in high-risk youth or whether the passage of time would have accomplished the same result. Relatedly, this study could not determine whether any form of psychosocial intervention, whether or not it involved the family, would have been associated with significant reductions in mood symptoms. Longer-term follow-up (i.e., four years or more) would be necessary to determine whether the addition of FFT-HR to usual care reduces the likelihood of syndromal manic onset, and, in turn, whether improvements in family affect, communication, or problem solving mediate the likelihood or timing of this endpoint.

We also cannot rule out the explanatory effects of medications on the observed symptom outcomes. Although medication regimens were largely stable during the period of study, they were also quite variable, and the sample size precluded examining each medication in relation to symptom severity. For example, a larger sample would have enabled an examination of whether psychostimulants (3/13, or 23% of cases) were associated with the emergence of manic or mixed symptoms among high-risk youth.

Only three studies have examined whether early intervention with mood stabilizers has preventative effects on children at risk for BD. In an open trial, Chang et al. (8) showed that children with subthreshold mood symptoms and a positive family history of BD improved with divalproex over 12 weeks. DelBello et al. (9) reached a similar conclusion in an open trial of quetiapine. The single randomized, controlled trial (RCT) comparing divalproex and placebo found that children with BD-NOS or cyclothymia and at least one biological parent with BD-I did not differ on time to medication discontinuation due to a mood event (10). Thus, evidence for the effectiveness of specific forms of pharmacotherapy in high-risk youth is quite limited. Nonetheless, in future RCTs involving psychosocial interventions, the impact of pharmacotherapy should be examined through implementing medication algorithms administered by psychiatrists who are blind to psychosocial treatment conditions.

We were unable to examine whether FFT-HR was equally effective with youth with different risk subtypes (e.g., MDD versus BD-NOS) or with comorbid disorders that might have affected youths’ responses to the skill-building strategies (for example, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder). We also were unable to determine whether attributes of the parent (e.g., whether it was the mother or father who had BD, or whether he or she had BD-I or BD-II) were associated with the degree of clinical response or attrition rates.

Fortunately, randomized trials of psychotherapy in BD and MDD youth are beginning to unravel the role of moderators of response. For example, we found in an earlier RCT that adolescents with BD-I or BD-II who were in high-EE families showed a greater magnitude of response to FFT than adolescents in low-EE families (28). In contrast, in the Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study, adolescents who described their family environments as more negative showed a poorer response to cognitive-behavioral therapy and a better response to fluoxetine (34). Identifying moderators of response in high-risk populations will be increasingly important as the number of evidence-based treatment options grows (35).

Finally, examining the impact of psychosocial interventions on the social and academic functioning and quality of life of high-risk youth—dimensions which are compromised substantially in this population (4, 36)—should be a key objective of future trials. Preventing or minimizing the toxic and impairing effects of early episodes before they become recurrent may help prevent the long-term functional disability caused by bipolar illness.

Acknowledgments

DJM has received funding from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), the Danny Alberts Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the Robert L. Sutherland Foundation; and royalties from Guilford Press and John Wiley & Sons. KDC has received research funding from NARSAD, NIMH, and GlaxoSmithKline; and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly & Co., Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck.

Financial support for this study was provided by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants MH077856 and MH073871 to DJM and an Independent Investigator Award to KDC from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD). The authors thank David Axelson, M.D., Victoria Cosgrove, Ph.D., Julia Maximon, M.D., Kathleen Kline, M.D., Marianne Wamboldt, M.D., Christopher Hawkey, Tenah Acquaye, Aimee Sullivan, Erica Weitz, Dana Elkun, Jedediah Bopp, and Jessica Lunsford for their assistance. Copies of the treatment manual may be obtained from DMJ. LMD was the statistical consultant.

Footnotes

DOT, ELG, MKS, CDS, LMD, MEH, and JG do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, et al. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavuluri MN, Birmaher B, Naylor MW. Pediatric bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2005;44:846–871. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000170554.23422.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:795–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL. Bipolar disorder at prospective follow-up of adults who had prepubertal major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:125–127. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strober M, Carlson G. Bipolar illness on adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacologic predictors in a 3–4 year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:549–555. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290050029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochman FJ, Hantouche EG, Ferrari P, Lancrenon S, Bayart D, Akiskal HS. Cyclothymic temperament as a prospective predictor of bipolarity and suicidality in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang KD, Dienes K, Blasey C, Adleman N, Ketter T, Steiner H. Divalproex monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar offspring with mood and behavioral disorders and at least mild affective symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:936–942. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DelBello MP, Adler CM, Whitsel RM, Stanford KE, Strakowski SM. A 12-week single-blind trial of quetiapine for the treatment of mood symptoms in adolescents at high risk for developing bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:789–795. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Findling RL, Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex monotherapy in the treatment of symptomatic youth at high risk for developing bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;68:781–788. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL. A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:904–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rea MM, Tompson M, Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Hwang S, Mintz J. Family focused treatment vs. individual treatment for bipolar disorder: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:482–492. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, et al. Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder: results of a 2-year randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME. Impact of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1013–1021. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West AE, Henry DB, Pavuluri MN. Maintenance model of integrated psychosocial treatment in pediatric bipolar disorder: A pilot feasibility study. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2007;46:205–212. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246068.85577.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waxmonsky J, Pelham WE, Gnagy E, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of methylphenidate and behavior modification in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and severe mood dysregulation. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:573–588. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nadkarni RB, Fristad MA. Clinical course of children with a depressive spectrum disorder and transient manic symptoms. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:494–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. (Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 (Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DelBello MP, Carlson GA, Tohen M, Bromet EJ, Schwiers M, Strakowski SM. Rates and predictors of developing a manic or hypomanic episode 1 to 2 years following a first hospitalization for major depression with psychotic features. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:173–185. doi: 10.1089/104454603322163899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised (CDRS-R) Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2001;40:450–455. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, et al. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semi-structured interview: test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, George EL, et al. Expressed emotion moderates the effects of family-focused treatment for bipolar adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2009;48:643–651. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a0ab9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miklowitz DJ. The role of family systems in severe and recurrent psychiatric disorders: a developmental psychopathology view. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:667–688. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein TR, Miklowitz DJ, Mullen K. Social skills knowledge and performance among adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:350–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weisman AG, Tompson MC, Okazaki S, et al. Clinicians’ fidelity to a manual-based family treatment as a predictor of the one-year course of bipolar disorder. Fam Process. 2002;41:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.40102000123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Davila J. A growth curve analysis of the effects of chronic stress on the course of dysthymic disorder: moderation by adverse parent-child relationships and family history. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1012–1021. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feeny NC, Silva SG, Reinecke MA, et al. An exploratory analysis of the impact of family functioning on treatment for depression in adolescents. J Clin Child Adol Psychol. 2009;38:814–825. doi: 10.1080/15374410903297148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: A strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang KD, Adleman N, Dienes K, Reiss AL, Ketter TA. Bipolar offspring: a window into bipolar disorder evolution. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:941–945. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]