Abstract

Arterial elasticity has been proposed as an independent predictor of cardiovascular diseases and mortality. Identification of the different propagating modes in thin shells can be used to characterize the elastic properties. Ultrasound radiation force was used to generate local mechanical waves in the wall of a urethane tube or an excised pig carotid artery. The waves were tracked using pulse-echo ultrasound. A modal analysis using two-dimensional discrete fast Fourier transform was performed on the time–space signal. This allowed the visualization of different modes of propagation and characterization of dispersion curves for both structures. The urethane tube∕artery was mounted in a metallic frame, embedded in tissue-mimicking gelatin, cannulated, and pressurized over a range of 10–100 mmHg. The k-space and the dispersion curves of the urethane tube showed one mode of propagation, with no effect of transmural pressure. Fitting of a Lamb wave model estimated Young’s modulus in the urethane tube around 560 kPa. Young’s modulus of the artery ranged from 72 to 134 kPa at 10 and 100 mmHg, respectively. The changes observed in the artery dispersion curves suggest that this methodology of exciting mechanical waves and characterizing the modes of propagation has potential for studying arterial elasticity.

INTRODUCTION

Arterial elasticity has gained importance as an independent predictor of cardiovascular diseases and mortality.1, 2, 3 It has been associated with multiple comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes,4, 5 hypertension,6 coronary artery disease,7 end-stage renal disease,8 and the list keeps growing as we learn more about the stiffening process of arteries and how it affects multiple organs.

There are multiple techniques and methodologies that have been developed to characterize the mechanical properties of arteries in vivo. These techniques are used to assess the systemic arterial stiffness, or the regional∕segmental stiffness of the arterial tree, or local stiffness of small vascular segments.

One of the most used techniques measures the speed of the propagation of the pressure wave to estimate the stiffness of the arteries.4, 9, 10 This technique is known as the pulse wave velocity (PWV), and it measures the time of propagation between two distant points in the arterial tree (usually the carotid and the femoral or the carotid and the radial) and calculates the speed of propagation as Eq. 1

| (1) |

where D is the distance traveled by the wave, and t is the time of propagation.

The modified Moens–Korteweg equation [Eq. 2] has been used to calculate Young’s modulus as a function of the propagating speed (PWV), the thickness (h), radius (R), Poisson’s ratio (ν), and the density of the artery (ρ)11:

| (2) |

Although this technique has been used extensively, it has multiple disadvantages. The calculation of the speed can be biased by the distance of the segment (ΔD) that the pressure wave travels, which can only be guessed since the real length of the arterial segment inside the body cannot be assessed noninvasively. Another disadvantage is that due to the low frequency of the pressure wave and the change of waveform in the arterial tree, determining the time of travel (Δt), which is often measured from foot to foot of the pressure wave, can be inaccurate. One more disadvantage that arises from the low frequency of the pressure wave is low spatial resolution of this method. Considering a heart rate of 1–2 Hz and a speed of propagation in arteries around 5 m∕s,12 the wavelength would be 2.5–5 m, which makes measuring the time shift between two points very difficult unless they are separated by a long distance. This makes the PWV technique only effective in the study of generalized mechanical properties of long arterial segments but not for the small segments or localized portions of the arterial tree, which can be of significant interest in diseases such as atherosclerosis.

Recent work by Konofagou and coworkers13 used speckle tracking to measure the velocity of propagation of the pressure wave. This approach can be used to study short segments of the arterial tree. Nevertheless, this method does not solve the problems with the temporal resolution (since it used the low frequency pressure wave) and therefore cannot be used to study some dynamic physiological phenomena of interest.

Other methodologies have focused on characterizing the properties from a qualitative point of view, such as the augmentation index, pressure waveform analysis, and ambulatory arterial stiffness index. These techniques have been useful for correlating changes in the mechanics of the arterial tree with disease processes and conditions in large populations.1 Unfortunately, they rely on accurate measurements of arterial pressure and transfer functions, which are difficult to determine noninvasively.14

Some techniques that quantify the local mechanical properties of arteries use the change in the diameter as a function of pressure to estimate the compliance and the distensibility of the vessels. The diameter of the vessels can be measured using ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography. The drawback of this approach is that it requires invasive measurement of arterial pressure at the point where the diameter is being measured.15

A more recent technique uses magnetic resonance to measure the propagation of guided waves in tissues, which is called magnetic resonance elastography. This technique has been applied to excised arteries and soft tubes with good preliminary results16, 17 and could provide a qualitative, noninvasive, and reproducible approach to the problem in question. The drawback is the high cost of this methodology, since it requires very specialized equipment and personnel and also the fact that it could only be performed in institutions with magnetic resonance scanners. The need for preventive medicine and tools to predict cardiovascular events, years if not decades before it happened, is of great importance.18

In this paper, we continue with the work from our laboratory presented by Zhang et al. (2003)19 where he used amplitude modulated (AM) ultrasound radiation force to generate mechanical waves in the arterial walls. Here we present a variation of this method, where instead of using AM we use short tonebursts of focused ultrasound to generate broadband guided waves in the arterial wall. This allows us to study the propagation of guided waves at multiple frequencies simultaneously, therefore better characterizing the behavior of the vessel wall. We also present an analysis to identify the different modes propagating simultaneously. The two-dimensional (2D) discrete fast Fourier transform (DFFT) has been used before to obtain dispersion curves of waves.20 We report here the first application of the 2D DFFT or k-space for characterizing waves in the arterial wall. We are confident that this kind of analysis will help in understanding of the dynamic elastic properties of vessels throughout the arterial tree and could potentially be used for clarifying the effect of stiffening in the different disease processes.

METHODS

Theory

A complete analytical solution of mechanical wave dispersion in elastic tubes submerged in water is required to completely characterize the motion of vessels due to radiation force. The complexity of potential functions describing such motion makes solving the equations for the boundary conditions very difficult. However, the lower most orders of longitudinal guided wave propagation in tubes can be approximated by the antisymmetric (A0) Lamb wave mode in plates.21, 22

What follows is the derivation of a plane Lamb wave dispersion equation for a homogenous elastic plate submerged in an incompressible water-like fluid. The Stokes–Helmholtz decomposition of the displacement field [Eq. 3] in the Navier’s equilibrium equation [Eq. 4] will be the starting point of the derivation. Details on the equilibrium equations, basic wave equations, and displacement field theorems can be found in Refs. 23, 24, 25, 26. The displacement field vector u can be written as a sum of a gradient of a scalar φ and the curl of a divergence-free vector potential , as shown in Eq. 3. Introducing the decomposition of Eq. 3 to the Navier’s equilibrium equation with zero equivalent body force [Eq. 4] allows for separation of variables resulting in two wave equations: one for the compressional [Eq. 5] and one for the shear wave [Eq. 6]

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where ∇• is the divergence, ∇ × is the curl, ∇ is the gradient, ρ is the material density, and λ and μ are the first and second Lamé constants. A more convenient way of expressing Eqs. 5, 6 is in terms of the compressional and shear wave velocities cp and cs

| (7) |

| (8) |

where and .

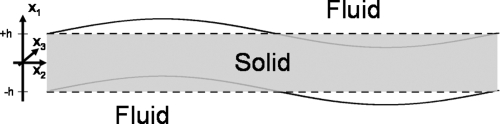

In the case of a plane wave propagation in a plate as shown in Fig. 1, the displacement is independent of the x3-axis, so u3 = ∂∕∂x3 = 0. This condition simplifies the curl operator in Cartesian coordinates, and introducing this simplification into Eqs. 3, 7, and 8 yields the following solutions of the potential functions φ and ψ:

| (9) |

| (10) |

where , , kL is the Lamb wave number, ks is the shear wave number, and kP is the compressional wave number. The time dependence of e−iωt is assumed for all potential functions but is omitted for clarity and brevity. Definitions of hyperbolic sine and cosine functions 2sinh(x) = (ex − e−x) and 2cosh(x) = (ex + e−x) were used to rewrite Eqs. 9, 10 for the reasons that will soon be apparent. The vector sign for the potential function ψ in Eq. 10 was omitted since we are interested in magnitudes only.

Figure 1.

Color online A tube submerged in water is approximated by an elastic homogenous plate submerged in an incompressible fluid. The motion shown is an antisymmetric mode.

In antisymmetric Lamb wave motion (Fig. 1), the displacement of the solid in the x1-direction is antisymmetrically relative to the x2-axis, so the potential functions for the solid are as follows:

| (11) |

| (12) |

Since shear waves do not propagate in fluids, the potential functions characterizing the motion of the fluid above and below the solid are of the following forms:

| (13) |

| (14) |

where and kf is the wave number of the compressional wave in the fluid. Subscripts U and L represent the upper and lower fluid relative to the solid and are defined in terms of decaying and increasing exponential functions, respectively. Mathematically, both potentials can be satisfied with a sum of increasing and decreasing exponential functions, but one of the functions is discarded in order to avoid positive and negative infinity.

The boundary conditions at x1 = ±h for the antisymmetric plane Lamb wave motion of a plate in a fluid are , , and , where the stresses (σ) and the displacements tensors (u) are defined as follows:

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

where the comma in the subscript followed by a number indicates partial differentiation with respect to the coordinate number. Inserting Eqs. 11, 12, 13 into Eqs. 15, 16, 17, 18 and solving for the boundary conditions yields a system of three equations with three unknowns. This can be written as a 3 × 3 matrix multiplied by a 3 × 1 column vector containing the unknown constants A, D, and N. In order for the system to have nontrivial solutions, the determinant of the 3 × 3 matrix must be equal to zero. Setting the determinant to zero yields the antisymmetric Lamb wave dispersion equation [Eq. 19]

| (19) |

In Eq. 19, h is the half-thickness of the solid and ρf is the density of the fluid. In soft tissues, the first Lamé constant (λ) describing the bulk properties of the medium is much larger than the second Lamé constant (μ) describing the shear properties of the medium. Consequently, , the shear wave number, is much larger than the , the compressional wave number, where ρ and ω are the material density and angular frequency of the propagating wave. For the materials used in our study (urethane rubber, water, blood, and tissue), the compressional wave number of fluids (kf) is on the order of magnitude of the compressional wave number of the solid (kp). In addition, the Lamb wave number (kL) is on the order of magnitude of the shear wave number (ks), which allows us to make the following simplification: since kL » kp.22, 27 Since the densities for the solids and fluids used in our experiments are fairly similar, the dispersion Eq. 19 reduces to

| (20) |

where kL = ω∕cL is the Lamb wave number, cL is the frequency dependent Lamb wave velocity, , and h is the half-thickness of the plate-tube.

The Lamb wave dispersion Eq. 20 is fitted to the experimentally obtained dispersion data to estimate the second Lamé constant or the shear modulus of elasticity (μ).

Experiments

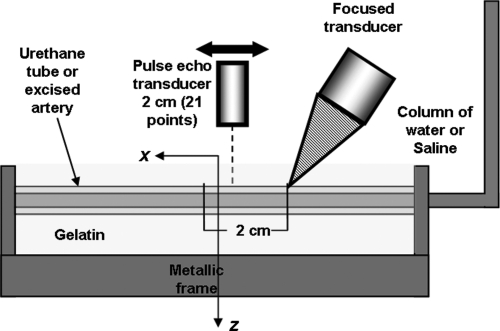

An excised carotid artery from a pig and a custom made urethane tube were used as models for the experiments. Both structures were mounted on a metallic frame, attached to a nozzle on each end, and prestretched. The artery was elongated to 1.4 times its recoil length to approximate the length in situ,28 while the urethane tube was elongated to 1.24 times its recoiled length which prevented it from bending due to the increasing pressure. The length of the artery was 7 cm between the two nozzles and the average diameter was 4.36 mm. For the tube experiment, the total length was around 14 cm and its mean diameter was 4.18 mm. To stabilize the structures and to mimic the surrounding tissues of arteries, the tube∕artery was embedded in a gelatin mixture with gelatin added at 10% by weight and a density of 1000 kg∕m3. The gelatin was allowed to set for 4–6 h, and then the entire setup was put in the refrigerator (4 °C) overnight. The experiments were done the next day.

On the day of the experiments, the phantom (artery or urethane tube) was submerged in a water tank. One end of the metallic frame was sealed while the other end was connected to a water or a saline column to change the transmural pressure.

To generate the mechanical waves, we used acoustic radiation force in which an acoustic signal (ultrasound signal in our case) can generate a pressure (force) that is proportional to the intensity of the signal radiated into the tissue and inversely proportional to the speed of the signal in the medium (in this case around 1500 m∕s for an ultrasound signal).29 In our experiments, we used a 3 MHz spherically focused ultrasound transducer (45 mm diameter, 70 mm focal length) as a noninvasive source of force. Five tonebursts were transmitted, each lasting 200 μs, and repeated at a frequency of 50 Hz generating a pulsatile force with a bandwidth of up to 5 kHz, since the length of each pulse was 200 μs. The vibration of the arterial wall was measured using pulse-echo ultrasound. The radio frequency data from a 7.5 MHz single element transducer (Valpey Fisher, Hopkinton, MA) and a cross-spectral method were used to find the velocity of vibration of the arterial wall as the wave generated by the ultrasound radiation force propagated.30 The cross-spectral method finds phase shifts between consecutive pulse-echo measurements to assess how much the artery has moved. This process is analogous to using cross-correlation to find time shifts and then associating them with motion of an object.31 The motion of the arterial wall was measured at twenty one points along the length of the vessel∕tube wall at a pulse repetition frequency of 4 kHz; each point 1 mm apart from each other, for a total length of 20 mm. At the beginning of the experiment, both transducers (focused and pulse-echo) were cofocused using a metallic pin as a target. Due to the size of the transducers, the confocal transducer was tilted at a 30°angle with the vertical axis (or 60°with the length of the vessel), while the pulse-echo transducer was perpendicular to the length of the vessel. See Fig. 2 for a depiction of the experimental setup, where the x1 axis from Fig. 1 is referred as z, x2 as x, and x3 as y (which is not shown in Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Color online Experimental setup for urethane or excised pig artery. A focused ultrasound transducer was used to generate mechanical waves and pulse-echo transducer was used to measure the speed of the propagating wave. A column of water was used to change the transmural pressure. Both the tube and the artery were embedded in a gelatin which mimics the surrounding properties of tissue.

To study the effect of pressure on the speed and modes of propagation, the transmural pressure across the artery or tube wall was changed from 10 to 100 mmHg in increments of 10 mmHg using the column of water∕saline.

Analysis

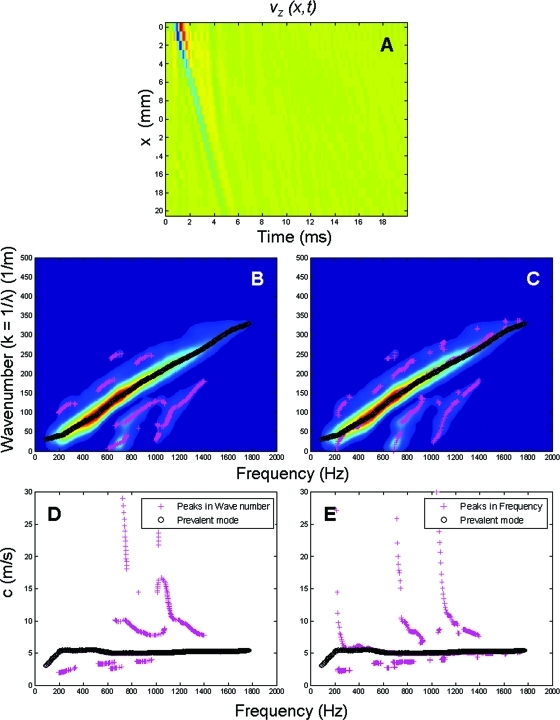

The process to go from the time signal of the propagating wave (time–space) to the dispersion curves is depicted in Fig. 3. Using Eq. 21 on the time–space signal in Fig. 3A, we obtain the representation of the respective k-space using the 2D DFFT from

| (21) |

where vz(x, t) is the velocity of motion of the arterial wall in the radial direction (z, in the direction of the pulse-echo transducer), which is a function of the distance along the artery (x) and time (t), k is the wave number, and f is the frequency of the wave. H(k, f) is the k-space representation of the propagating wave. The x-axis represents frequency and the y-axis represents the wave number (k or 2πf∕λ).

Figure 3.

Diagram describing the process to determine the dispersion curves for the tube and the artery from the time–space signal. Panel A shows an example of a guided wave propagating in time and space in an arterial wall. Panels B and C shows the masked 2D DFFT or H(k, f) of the signal in panel A, where the x-axis represents frequency and the y-axis the wave number (k = 1∕λ, where λ is the wavelength). Black circles show the dominant or highest energy mode for each frequency [first antisymmetric Lamb wave-like mode (A0)]. In panel B, the magenta crosses represent the peaks found using the partial derivative in the frequency direction, corresponding to higher order modes. Similarly in panel C, the magenta crosses represent the peaks found using the partial derivative in the wave number direction. Panels D and E show the dispersion curves; as in panels B and C, the black circles show the mode of maximum energy and the magenta crosses the higher order modes.

To obtain the dispersion curve we first threshold the k-space using an amplitude mask. The threshold was empirically set to the maximum of the field divided by 13. Figures 3B, 3C show both the masked k-space where the filtering process preserved the high amplitude content while eliminating most of the noise in the k-space. To identify the multiple modes of propagation from H(k, f), first we found the dominant mode or highest energy mode by identifying the maximum amplitude for each value of frequency and its corresponding wave number (k) [black circles in Figs. 3B, 3C]. The characterization of the higher order modes (lower energy) was done in two ways using the partial derivatives of H(k, f). We used the first and second partial derivative with respect to frequency [Eq. 22] to identify the different amplitude peaks in the k-space for each frequency and then determine the wave number associated with it [magenta crosses in Fig. 3B]

| (22) |

Then we proceeded to do the same process for the wave number direction. The first and second derivatives [Eq. 23] were used to find the amplitude peaks of the k-space for each wave number and then find the frequency associated with it [magenta crosses in Fig. 3C]

| (23) |

Basically, this method involved finding the peaks in the frequency direction and finding the peaks in the wave number direction.

Using the paired values of frequency and wave number for all the peaks in the k-space, we calculated the dispersion curves using Eq. 24

| (24) |

where c is the dispersion velocity of the propagating wave, f is the frequency or the x-axis of the k-space plot, and λ is the wavelength or 1∕k (in this case 1∕y-axis). Figure 3D shows the dominant mode (black circles) as well as the higher modes (magenta crosses) calculated in the frequency direction. Figure 3E shows the dominant mode and the higher order modes calculated in the wave number direction.

The group velocity of the generated mechanical wave was calculated using cross-correlation of the time signal vz(t) shown in Fig. 4B (although the five excitation pulses were used for a better cross-correlation). For evaluation of the cross-correlation, we define the reference signal, sr(t) as vz(t) at the excitation position and sd(t) is the delayed signal measured at each of the points along the x-direction. The normalized cross-correlation between two signals, sr(t) and sd(t) is given according to Eq. 2531

| (25) |

where T is the window length for the reference signal, is the mean value of the reference signal over the window T, and is the mean value of the delayed signal over the length of the sliding window. These mean values can be written as

| (26) |

| (27) |

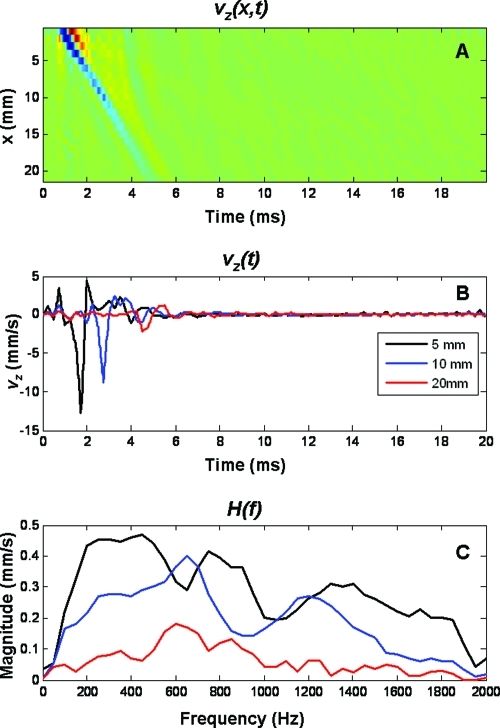

Figure 4.

Panel A shows the time-space propagation of a guided wave over 20 mm. Panel B shows three representative time signals at 5, 10, and 20 mm from the excitation point. Panel C shows the respective frequency spectra [H(f)] of the time signals presented in panel B.

The function cn(τ) reaches its maximum when sd(t) = sr(t − Δt), where Δt is the time shift between the signals sr(t) and sd(t). In our implementation, an added step fits a cosine to the peak of the cn(τ) peak to achieve finer time resolution.32 The time shifts can be used to find the group velocity using the following equation:

| (28) |

where Δd is the distance between measurement points. For each measurement point, we obtain a time shift. A linear regression was applied to the time shifts versus distance to find the group velocity.

RESULTS

Figure 4A shows the motion generated by the focused transducer (the color code means the velocity of the wall moving perpendicular to the pulse-echo transducer) and the propagating guided wave along the 20 cm of the vessel front wall. This is a representative measurement made at a 50 mmHg of transmural pressure. Figure 4C shows the frequency spectrum of the motion at three different positions (5, 10, and 20 mm) away from the excitation point.

Even though the focused transducer was focused at the front wall, the focal spot is long enough (∼10 mm) that it would push on both walls, front and back. Comparison of the motion of the two walls showed an antisymmetric Lamb-like behavior that is both walls were moving in the same direction at the same time (data not shown). Because the signal-to-noise ratio was better in the front wall data, we decided to use this data for the analysis of the material properties of the arterial wall.

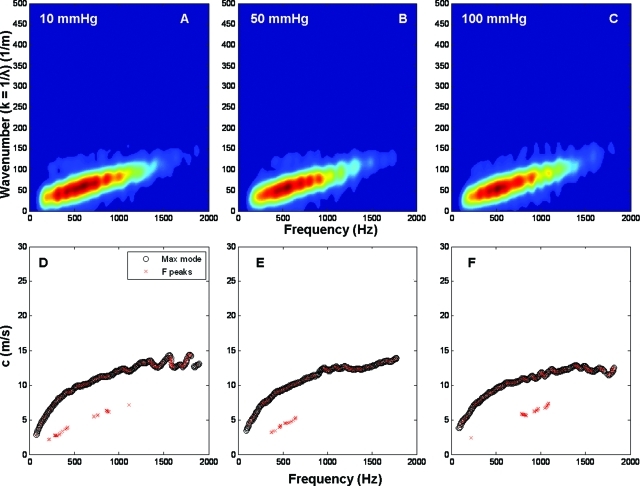

Figure 5 shows the k-space plots and the dispersion curves for the urethane tube at three different pressures. In the first row, panels A, B, and C correspond to 10, 50, and 100 mmHg, respectively. The second row is the corresponding dispersion diagram calculated from the k-space as explained in the Methods section.

Figure 5.

K-space and dispersion diagrams for urethane tube. Panels A, B, and C show the k-space representation for the urethane tube at three different pressures (10, 50, and 100 mmHg). Panels D, E, and F show the respective dispersion diagrams, where the black circles represent the highest energy mode and the red crosses the peaks found in the frequency direction. The peak results in the wave number direction are not presented since they only added noise to the figures.

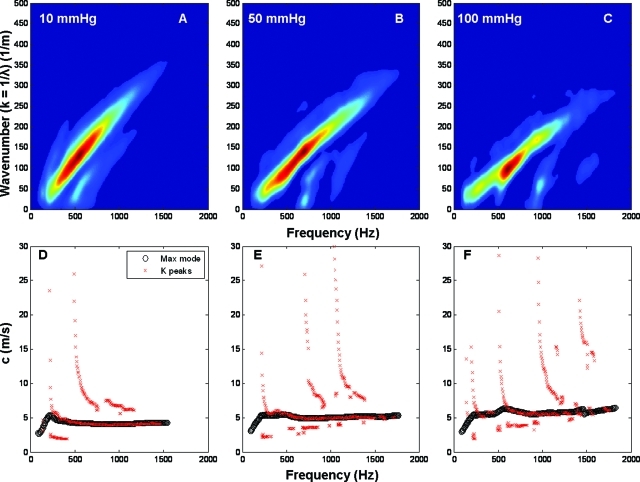

Similarly, Figure 6 shows the results for the excised artery. In the first row are the k-space plots for 10 (A), 50 (B), and 100 mmHg (C). The corresponding dispersion diagrams are on the second row.

Figure 6.

K-space and dispersion diagrams for excised pig carotid artery. Panels A, B, and C show the k-space representation for the artery at three different pressures (10, 50, and 100 mmHg). Panels D, E, and F show the respective dispersion diagrams, where the black circles represent the highest energy mode and the red crosses the peaks in the wave number direction. The peak results in the frequency direction are not presented since they failed to track the higher order modes.

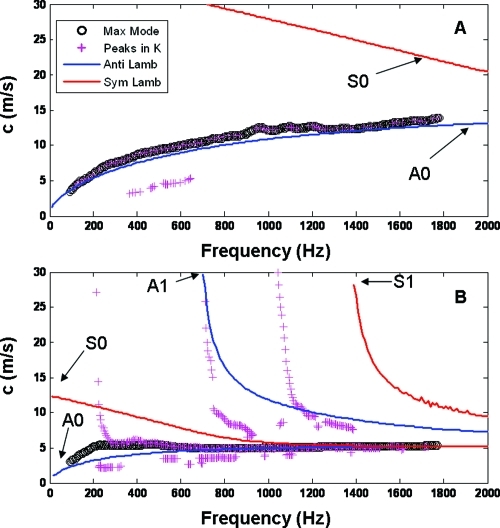

Using the Lamb wave model described in the Methods section and the geometrical values (diameter) from the pulse-echo measurements, we varied the values for shear modulus until we achieved a good fit of the first antisymmetric Lamb wave mode (A0) to the dispersion curves shown in Figs. 56 for the highest energy mode. Figure 7A shows the fitting for the urethane tube, and Fig. 7B shows the result for the excised artery with a transmural pressure of 50 mmHg.

Figure 7.

Experimental dispersion curves and fitting of a Lamb wave model. Panel A shows the dispersion curve for the urethane tube at 50 mmHg. The black circles represent the highest energy mode while the magenta circles the peaks in the wave number direction. The blue and the red lines represent the antisymmetric (A) and symmetric (S) modes for the Lamb wave model. Similarly, panel B show the dispersion curves and Lamb wave fitting for the artery at 50 mmHg. The legend from panel A applies to panel B.

Tables 1, TABLE II. show the results for all the pressures for the urethane tube and the excised artery, respectively. In the first column, the values for the group velocity for each pressure are given, calculated as described in the Methods section. For comparison, the phase velocity values from the dispersion curves at half the bandwidth of the time signal (900 Hz for both cases) are given in the second column. In the third column, the shear modulus values for the ten transmural pressures from the Lamb wave model are given, and in the fourth column, Young’s modulus values calculated as three times the shear modulus assuming incompressibility of tissue are given (sum of the strains in all directions must be equal to zero). In the fifth column, Young’s modulus calculated using the Moens–Korteweg equation, which has been used extensively in the study of arterial elasticity using the pressure wave are given.

Table 1.

Results for the urethane tube for group velocity, phase velocity at 900 Hz, shear modulus (μ), Young’s modulus (calculated as 3μ), and Young’s modulus from the Moens–Korteweg equation for pressures between 10 and 100 mmHg.

| Pressure (mmHg) | Group velocity (m∕s) | Phase velocity at 900 Hz (m∕s) | Shear modulus (μ) (kPa) | Young’s modulus (E = 3μ) (kPa) | Young’s modulus (Moens–Korteweg) (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 11.24 | 11.29 | 183.55 | 550.65 | 441.87 |

| 20 | 11.48 | 11.56 | 192.37 | 577.11 | 483.81 |

| 30 | 11.23 | 11.69 | 196.88 | 590.57 | 445.33 |

| 40 | 11.35 | 11.75 | 198.89 | 596.67 | 457.27 |

| 50 | 11.08 | 11.41 | 187.53 | 562.58 | 438.12 |

| 60 | 11.22 | 11.37 | 186.17 | 558.50 | 450.65 |

| 70 | 10.84 | 11.17 | 179.70 | 539.09 | 423.92 |

| 80 | 10.84 | 11.17 | 179.70 | 539.09 | 423.92 |

| 90 | 10.96 | 10.92 | 171.82 | 515.47 | 436.25 |

| 100 | 11.01 | 10.97 | 173.44 | 520.32 | 442.86 |

Table 2.

Results for the excised pig carotid for group velocity, phase velocity at 900 Hz, shear modulus (μ), Young’s modulus (calculated as 3μ), and Young’s modulus from the Moens–Korteweg equation for pressures between 10 and 100 mmHg.

| Pressure (mmHg) | Group velocity (m∕s) | Phase velocity at 900 Hz (m∕s) | Shear modulus (μ) (kPa) | Young’s modulus (E = 3μ) (kPa) | Young’s modulus (Moens–Korteweg) (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 4.12 | 4.10 | 24.22 | 72.65 | 68.70 |

| 20 | 4.17 | 4.22 | 25.69 | 77.08 | 76.31 |

| 30 | 4.46 | 4.47 | 28.72 | 86.18 | 93.01 |

| 40 | 4.73 | 4.73 | 32.18 | 96.54 | 107.01 |

| 50 | 4.94 | 4.96 | 35.48 | 106.45 | 118.82 |

| 60 | 5.09 | 5.12 | 37.72 | 113.18 | 127.14 |

| 70 | 5.22 | 5.28 | 39.88 | 119.64 | 134.67 |

| 80 | 5.35 | 5.41 | 42.15 | 126.45 | 142.44 |

| 90 | 5.44 | 5.44 | 42.64 | 127.93 | 148.30 |

| 100 | 5.50 | 5.57 | 44.71 | 134.12 | 152.38 |

DISCUSSION

The propagation of the guided wave in the wall of an excised artery was shown in Fig. 4A. Note that besides the main propagating mode, there seems to be some other wave that propagates at a faster speed and the speed changes as it propagates away from the excitation point. Therefore a modal analysis of this signal can potentially give more insight to the material properties of the arterial wall. Also, it is important to note the frequency spectrum of the wave generated with the radiation force in Fig. 4C. The bandwidth of the signal goes from 50 to 1900 Hz, making this wave a broadband signal which allows the study of the properties of the arterial wall at a wider range of frequencies.

In the k-space for the tube (Fig. 5), there are hardly any differences between the different pressures (A, B, and C). This was expected since the urethane tube behaves as a linearly elastic material at the strain levels seen in the experiment (transmural pressure). Therefore the dispersion curves presented in the second row of Fig. 5 show the same behavior with very similar speeds at high frequencies. Also, it is important to note that there is only one mode propagating along the wall, and this could be seen both in the k-space and the dispersion plots.

On the contrary, the arteries showed a significant change in their k-space plots with transmural pressure, not only changing the slope of the main mode but also showing two or three modes propagating at the same time [Figs. 6A, 6B, 6C]. These modes of propagation can also be seen in the dispersion curves on the second row of Fig. 6, where the main mode is presented as the black circles and the higher modes in red crosses. Also, it is important to notice how the frequency at which these modes appear increases with transmural pressure; this can be explained by the stiffening of the arterial wall due the increased pressure.

Lamb waves have been used in the study of the mechanical properties and defect analysis of plates, and the theory has also been proposed as a good approximation for tubes with a thickness to radius ratio of 0.2.21 In our experiments the thickness to radius ratio was around 0.28 and 0.24 for the tube and the artery, respectively. In Fig. 7, we presented the dispersion curves for the urethane tube and artery (panels A and B, respectively), where the black circles represent the main mode and the magenta crosses the higher modes. In the case of the tube, it is clear that there is only an A0-like Lamb wave mode, where A is used for antisymmetric wave modes and S is used for symmetric wave modes, while in the artery (panel B) there are multiple higher order modes (A1- and S1-like modes). The blue and the red lines represent the results of the Lamb wave model fitting for symmetric and asymmetric modes. The input parameters for the model were the diameter obtained from the pulse-echo measurement at 50 mmHg for the tube and the artery, the density of both structures (close to 1000 kg∕m3), the density of the liquid inside (water or saline), and the frequency range to explore.

In Lamb wave theory of plates, the velocity at which the dispersion curve for the A0 mode plateaus is referred to as the Rayleigh wave speed, and it is the value at which the A0 and S0 modes converge when the frequency is high enough that the propagating wave is no longer affected by the thickness of the sample. In our data, we observed a difference in the dispersion of the main mode between the tube and the artery. The tube shows an increasing speed from low frequencies up to 2 kHz, without showing a plateau of the speed in our frequency range [Fig. 7A]. Nevertheless, the rate of change of the speed with frequency decreases implying that the plateau speed is reached at higher frequencies. The speed data for the artery in Fig. 7B reaches the plateau speed (Rayleigh speed) at around 500 Hz and after that the higher modes seem to converge to this value [Fig. 7B]. The Lamb wave model shows good agreement for both the tube and the artery data, showing a single mode for the tube in our frequency range, while showing multiple modes close to the experimental data for the artery. In the case of the artery, by 900 Hz (half the bandwidth of the time signal), the A0-like mode and the S0-like mode have already converged, while for the urethane tubes, the speed of propagation at half the bandwidth differs from the plateau speed.

Some of the discrepancies between the Lamb wave model and the experimental data are: the shape of the A0-like mode at low frequencies and the frequencies at which the A0 and S0 modes come down to the Rayleigh speed. These discrepancies can be due to the fact that the Lamb model used is described for an elastic material, not a viscoelastic material which makes up the arteries. Also, the model is for a plate and not a tube, and although it has been shown to be good approximation there is some refining that needs to be done. Also, the model does not account for transmural pressure which can also play a significant role. Nevertheless the fact that higher modes can be seen in arteries is of great relevance since this could motivate the creation of better mathematical models for this kind of problem, where a cylindrical, anisotropic, nonlinear material is described. Unfortunately, analytical solutions for these models have yet to be developed.

The group velocity is described by Morse and Ingard as the “velocity of progress of the ‘center of gravity’ of a group of waves that differ somewhat in frequency.”33 In this study, the group velocity was measured using the time delay between multiple points by cross-correlation of the time signals. Since the wave generated by the radiation force is a broadband wave, we compared the group velocity to the phase velocity at half the bandwidth. These two values were in good agreement for all the transmural pressures, for both the tube and the artery as shown in Tables 1, TABLE II., first and second rows.

Nevertheless, it is important to note a big difference between the artery and the tube data. Over the bandwidth of our signal, the artery dispersion curve reached the plateau velocity at 500 Hz [Rayleigh like speed, Figs. 6D, 6E, 6F, 7B], while in the tube, it is clear from Figs. 5D, 5E, 5F, 7A that the plateau velocity has not been reached until 2 kHz. Therefore, the interpretation of the group velocity is problematic, because while the arterial group velocity is the same as the plateau velocity, or the velocity at which the multiple modes will converge; the group velocity of the urethane tube does not represent this value since the bandwidth does not include higher frequencies.

The third column in Tables 1, TABLE II. is the shear modulus (μ) that was used to get an appropriate fit of the Lamb wave model on the dispersion data. The fourth column is Young’s modulus (E) calculated as three times the shear modulus. Since the group velocities obtained in the arteries with our technique were very similar to the ones reported in the literature for the PWV,4, 9, 10, 12, 13, 34, 35 we used the Moens–Korteweg equation to get an estimate of Young’s modulus. The results from this equation are presented in the fifth column. Interestingly, the values for elasticity in the arteries with the Moens-Korteweg equation and with the Lamb wave model were very similar despite the different origins and natures of the two waves (pressure wave and the wave generated in our experiments). This seems to suggest that in arteries, where the group velocity is the same as the plateau velocity, the Moens–Korteweg equation could be used as a simple way to calculate the elasticity of the arterial wall. Nevertheless, a more complex mathematical model that captures the different modes of propagation in the arterial wall is required to characterize the elasticity and viscosity in the different orientations of the vessel wall. However, in the urethane tubes the use of the Moens–Korteweg equation underestimated the elasticity values. We believe that this was due to the fact that the group velocity underestimated the plateau velocity, since the bandwidth of our signal was not high enough to capture the speed at which the multiple modes converge. More research comparing the pressure wave and the wave generated with ultrasound radiation force needs to be done to evaluate if the Moens–Korteweg equation could in fact be used to estimate the elasticity of arteries, since the nature of these two waves is very different. In the future, we will explore how the speeds that we measure with large bandwidth pulses relate to speeds measured with conventional PWV.

Some other differences between the tube and the artery are that for the artery, the change in pressure generates an increase of the group and phase velocity which was expected since the components of the arterial wall have nonlinear elastic behavior.36 As the pressure increases the stress distribution shifts from the elastin fiber to the collagen fibers (much stiffer), therefore increasing the total stiffness of the arterial wall. Studies by Fung and others on arterial tissue have showed a nonlinear behavior of Young’s modulus.32, 37, 38, 39, 40. The tube on the other hand does not exhibit changes in either the group or the phase velocity at different pressures due to its linear elastic nature. This suggests that at these levels of transmural pressure there is no effect on the material properties of the tube in the frequency range explored.

As mentioned before, some of the disadvantages of the Lamb wave model are that it was developed for an isotropic, elastic plate. And even though the model seems to capture the overall nature of the propagating wave in the tube and the artery, some of the higher mode curves have different cut off frequencies than the model. This was to be expected since the arteries are anisotropic and viscoelastic materials, and although the Lamb wave model accounts for water loading conditions, it does not include the effect of anisotropy or viscoelasticity.

Multiple propagating modes in arteries have not been reported previously. With appropriate models, their in vivo measurement should allow more complete characterization of arterial properties. The temporal and spatial resolution of the method presented here along with the type of analysis would provide a tool to explore these modes of propagation and for analysis dynamic changes in physiology of local regions of arteries.

CONCLUSION

The importance of measuring the arterial mechanical properties is of great interest for the prediction of cardiovascular diseases and mortality. It has been associated with other comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, end-stage renal disease, and the list keeps growing as we learn more about the effect of arterial stiffness. In this paper, we present an ultrasound radiation force technique for the high temporal and spatial resolution measurement of the speed of propagation. We also showed that modal analysis for characterization of the multiple waves propagating simultaneously can help to better characterize the mechanical properties of arteries. Implementation of this methodology in a clinical ultrasound system would allow measurements of arterial elasticity in vivo and characterization of arterial properties within the cardiac cycle, which could help in the diagnosis and follow up of diseases processes and treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Randy Kinnick and Thomas Kinter for technical support and Jennifer Milliken for secretarial support. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant EB02640 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). Some of the authors have patents on parts of this work.

References

- Dolan E., Thijs L., Li Y., Atkins N., McCormack P., McClory S., O’Brien E., Staessen J. A., and Stanton A. V., “Ambulatory arterial stiffness index as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in the Dublin Outcome Study,” Hypertension 47, 365–370 (2006). 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200699.74641.c5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S., Boutouyrie P., Asmar R., Gautier I., Laloux B., Guize L., Ducimetiere P., and Benetos A., “Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients,” Hypertension 37, 1236–1241 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingwell B. A. and Gatzka C. D., “Arterial stiffness and prediction of cardiovascular risk,” J. Hypertens. 20, 2337–2340 (2002). 10.1097/00004872-200212000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. D., Bulpitt C. J., Pinto E. S., and Rajkumar C., “The aging of elastic and muscular arteries: A comparison of diabetic and nondiabetic subjects,” Diabetes Care 26, 2133–2138 (2003). 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft J. R., Wilkinson I. B., Evans M., McEwan P., Peters J. R., Davies S., Scanlon M. F., and Currie C. J., “Pulse pressure predicts cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus,” Am. J. Hypertens. 18, 1463–1467 1469; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; discussion 1468–1467 1469 (2005).

- Laurent S., Katsahian S., Fassot C., Tropeano A. I., Gautier I., Laloux B., and Boutouyrie P., “Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of fatal stroke in essential hypertension,” Stroke 34, 1203–1206 (2003). 10.1161/01.STR.0000065428.03209.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprez D. A. and Cohn J. N., “Arterial stiffness as a risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis,” Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 9, 139–144 (2007). 10.1007/s11883-007-0010-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin A. P., Blacher J., Pannier B., Marchais S. J., Safar M. E., and London G. M., “Impact of aortic stiffness attenuation on survival of patients in end-stage renal failure,” Circulation 103, 987–992 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell J. C. and Hill A. V., “The velocity of the pulse wave in man,” Proc. R. Soc., London: 298–0306 (1922). [Google Scholar]

- Latham R. D., Westerhof N., Sipkema P., Rubal B. J., Reuderink P., and Murgo J. P., “Regional wave travel and reflections along the human aorta: A study with six simultaneous micromanometric pressures,” Circulation 72, 1257–1269 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols W. and O’Rourke M., “Properties of arterial wall: Theory,” in McDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretical, Experimental and Clinical Principles, Arnold (Publisher) Hodder (London, 2005), pp. 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y. C., Arand P. W., Shroff S. G., Feldman T., and Carroll J. D., “Determination of pulse wave velocities with computerized algorithms,” Am. Heart J. 121, 1460–1470 (1991). 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90153-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vappou J., Luo J., and Konofagou E. E., “Pulse wave imaging for noninvasive and quantitative measurement of arterial stiffness in vivo,” Am. J. Hypertens. 23, 393–398 (2010). 10.1038/ajh.2009.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope S. A., Tay D. B., Meredith I. T., and Cameron J. D., “Use of arterial transfer functions for the derivation of aortic waveform characteristics,” J. Hypertens. 21, 1299–1305 (2003). 10.1097/00004872-200307000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinders J. M. and Hoeks A. P., “Simultaneous assessment of diameter and pressure waveforms in the carotid artery,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 30, 147–154 (2004). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrum D. A., Romano A. J., Lerman A., Pandya U. H., Brosh D., Rossman P. J., Lerman L. O., and Ehman R. L., “Vascular wall elasticity measurement by magnetic resonance imaging,” Magn. Reson. Med. 56, 593–600 (2006). 10.1002/mrm.v56:3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K. C. and Rutt B. K., “Polyvinyl alcohol cryogel: An ideal phantom material for MR studies of arterial flow and elasticity,” Magn. Reson. Med. 37, 314–319 (1997). 10.1002/mrm.v37:2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn J. N., “Arterial stiffness, vascular disease, and risk of cardiovascular events,” Circulation 113, 601–603 (2006). 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.600866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Kinnick R. R., Fatemi M., and Greenleaf J. F., “Noninvasive method for estimation of complex elastic modulus of arterial vessels,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 52, 642–652 (2005). 10.1109/TUFFC.2005.1428047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleyne D. and Cawley P., “A two-dimensional Fourier transform method for the measurement of propagating multimode signals,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89, 1159–1168 (1991). 10.1121/1.400530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. and Rose J. L., “Natural beam focusing of non-axisymmetric guided waves in large-diameter pipes,” Ultrasonics 44, 35–45 (2006). 10.1016/j.ultras.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu T., “Guided waves for plate inspection,” in Ultrasonic Nondestructive Evaluation: Engineering and Biological Material Characterization, edited by Kundu T. (CRC press, New York, 2003), pp. 223–310. [Google Scholar]

- Graff K. F., Wave Motion in Elastic Solids (Oxford University Press, London, 1975), pp. 273–310. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach J. D., Wave Propagation in Elastic Solids (Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2005), pp. 10–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rose J. L., Ultrasonic Waves in Solid Media (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1999), pp. 5–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu T., “Mechanics of elastic waves and ultrasonic nondestructive evaluation,” in Ultrasonic Nondestructive Evaluation: Engineering and Biological Material Characterization (CRC press, New York, 2003), pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kanai H., “Propagation of spontaneously actuated pulsive vibration in human heart wall and in vivo viscoelasticity estimation,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 52, 1931–1942 (2005). 10.1109/TUFFC.2005.1561662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. C. and Ku D. N., “Contractile responses in arteries subjected to hypertensive pressure in seven-day organ culture,” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29, 467–475 (2001). 10.1114/1.1376391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvazyan A. P., Rudenko O. V., and Nyborg W. L., “Biomedical applications of radiation force of ultrasound: Historical roots and physical basis,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 36, 1379–1394 (2010). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H. and Kanai H., “Improving accuracy in estimation of artery-wall displacement by referring to center frequency of RF echo,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 53, 52–63 (2006). 10.1109/TUFFC.2006.1588391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker W. F. and Trahey G. E., “A fundamental limit on delay estimation using partially correlated speckle signals,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 42, 301–308 (1995). 10.1109/58.365243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viola F. and Walker W. F., “A spline-based algorithm for continuous time-delay estimation using sampled data,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 52, 80–93 (2005). 10.1109/TUFFC.2005.1397352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse P. and Ingard K., Theoretical Acoustics (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1968), Chap. 9, pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- McEniery, Yasmin C. M.,Hall I. R., Qasem A., Wilkinson I. B., and Cockcroft J. R., “Normal vascular aging: Differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: The Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT),” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46, 1753–1760 (2005). 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke M. F., Staessen J. A., Vlachopoulos C., Duprez D., and Plante G. E., “Clinical applications of arterial stiffness; definitions and reference values,” Am. J. Hypertens. 15, 426–444 (2002). 10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02319-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrin P. B. and Canfield T. R., “Elastase, collagenase, and the biaxial elastic properties of dog carotid artery,” Am. J. Physiol. 247, H124–H131 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank A. J., Wang H., Holte J. E., Mullen K., Shammas R., and Kubo S. H., “Contribution of collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle to in vivo human brachial artery wall stress and elastic modulus,” Circulation 94, 3263–3270 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debes J. C. and Fung Y. C., “Biaxial mechanics of excised canine pulmonary arteries,” Am. J. Physiol. 269, H433–H442 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonck E., Prod’hom G., Roy S., Augsburger L., Rufenacht D. A., and Stergiopulos N., “Effect of elastin degradation on carotid wall mechanics as assessed by a constituent-based biomechanical model,” Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H2754–H2763 (2007). 10.1152/ajpheart.01108.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks M. S. and Sun W., “Multiaxial mechanical behavior of biological materials,” Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 5, 251–284 (2003). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]