Abstract

IFN regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) is a key transcription factor for myeloid cell differentiation and its expression is frequently lost in hematopoietic cells of human myeloid leukemia patients. IRF8-deficient mice exhibit uncontrolled clonal expansion of undifferentiated myeloid cells that can progress to a fatal blast crisis, thereby resembling human chronic myelogeneous leukemia (CML). Therefore, IRF8 is a myeloid leukemia suppressor. While the understanding of IRF8 function in CML has recently improved, the molecular mechanisms underlying IRF8 function in CML is still largely unknown. In this study, we identified acid ceramidase (A-CDase) as a general transcription target of IRF8. We demonstrated that IRF8 expression is regulated by IRF8 promoter DNA methylation in myeloid leukemia cells. Restoration of IRF8 expression repressed A-CDase expression, resulting in C16 ceramide accumulation and increased sensitivity of CML cells to FasL-induced apoptosis. In myeloid cells derived from IRF8-deficient mice, A-CDase protein level was dramatically increased. Furthermore, we demonstrated that IRF8 directly bind to the A-CDase promoter. At the functional level, inhibition of A-CDase activity, silencing A-CDase expression or application of exogenous C16 ceramide sensitized CML cells to FasL-induced apoptosis, whereas, overexpression of A-CDase decreased CML cells sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. Consequently, restoration of IRF8 expression suppressed CML development in vivo at least partially through a Fas-dependent mechanism. In summary, our findings determine the mechanism of IRF8 downregulation in CML cells and they determine a primary pathway of resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis and disease progression.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow (BM) give rise to all of the different types of blood cells through a hierarchical differentiation process. This hierarchical differentiation process is tightly regulated by key transcription factors that regulate the expression of lineage-specific genes (1). Aberrant expression of these transcription factors can result in altered lineage-specific differentiation process that can lead to leukemia (2–5). IFN regulatory factor 8 (IRF8, also known as Interferon Consensus Sequence Binding Protein or ICSBP) is such a key transcription factor (6–10). In humans, IRF8 expression is high in normal hematopoietic cells but impaired in myeloid leukemia (11, 12), where it has been observed that 79% of chronic myelogeneous leukemia patients and 66% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients have very low or absent IRF8 expression (11). Mice with a null mutation in IRF8 develop a myeloproliferative syndrome with marked expansion of undifferentiated myeloid cells that can progress to fatal blast crisis reminiscent of human chronic myelogeneous leukemia (CML) (2). Therefore, IRF8 functions as a tumor suppressor in myeloid leukemogenesis (3, 13–17).

The molecular mechanisms underlying IRF8 function in suppressing myeloid leukemia have been under extensive study (15, 18–23) but remain largely undefined. We report here that: 1) IRF8 functions as a transcriptional repressor of acid ceramidase (A-CDase) to mediate myeloid cell apoptosis; and 2) IRF8 functions as a tumor suppressor at least partially through regulating A-CDase expression to mediate CML sensitivity to Fas-mediated effector mechanism of the host immune system in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Tumor cell lines and specimens

The human cell lines K562, LAMA84 and HT29 were obtained from ATCC. Mouse CML cell line 32D was also obtained from ATCC. Peripheral blood was obtained from CML/AML patients in the Medical College of Georgia Medical Center. All studies with human specimens were carried out in accordance with approved NIH and Medical College of Georgia guidelines.

Mice

BALB/c mice were obtained from the NCI Frederick mouse facility (Frederick, MD). IRF8 knock out mice was maintained as described (2). Faslgld mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were housed, maintained and studied in accordance with approved NIH and Medical College of Georgia guidelines for animal use and handling.

RT-PCR analysis

RT-PCR analysis was carried out as previously described (24). The PCR primer sequences are as follows: human IRF8: forward: 5′-CCAGATTTTGAGGAAGTGACG-3′, reverse: 5′-TGGGAGAATGCTGAATGGTGC-3′; mouse IRF8: forward: 5′-CGTGGAAGACGAGGTTACGCTG-3, reverse: 5′-GCTGAATGGTGTGTGTCATAGGC-3′; mouse A-CDase: forward: 5′-CTTTTGGAGGAAATGAGGGG-3′, reverse: 5′-GTCTTGGTCAGTGTGTTCTTGGC-3 ′ and β-actin: forward: 5 ′-ATTGTTACCAACTGGGACGACATG-3′, reverse: 5 ′-CTTCATGAGGTAGTCTGTCAGGTC-3′. PCR band intensity was quantified using NIH Imager J program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Quantitative PCR reactions were done in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystem).

MS-PCR analysis

Sodium bisulfite modification of genomic DNA was carried out using CpGenome Universal DNA Modification Kit (Chemicon). MS-PCR primers were carried out as previously described (25). The PCR sequences are as follows: the human IRF8 promoter: unmethylated forward primer: 5′-CCATCCCCATAAAATAACACACAACAAA-3′, unmethylated reverse primer: 5′-GATGGTGTAGATGTGTGTTTGTGGTTT-3′, methylated forward primer: 5′-TCCCCGTAAAATAACGCGCGACGAA-3′, and methylated reverse primer: 5′-CGGTGTAGACGTGCGTTTGCGGTTT-3′. The mouse IRF8 promoter: unmethylated forward primer: 5′-TTTTGGGGTAGTTTTTTTTTTTGTTGTTTTT-3′, unmethylated reverse primer: 5′-TCCCACACACAAAACAACAATCACACA-3′, methylated forward primer: 5′-TGGGGTAGTTTTTTTTTTCGTCGTTTTC-3′, and methylated reverse primer: 5′-GCGCGCAAAACGACGATCGCGCG-3′.

Genomic DNA sequencing

The bisulfite-modified genomic DNA was used as template for PCR amplification of the mouse IRF8 promoter region. Bisulfite PCR primer pairs were designed using MethPrimer program (Chemcon). The Primer sequences are: forward: 5 ′-GGGATAGAGGTTTTTTAAATTTGAA-3 ′, reverse: 5 ′-AACAACCAAAACAAACACCTACTAAC-3′. The 503 bp PCR-amplified DNA fragment was cloned to pCR2.1 plasmid using TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The cloned DNA was then sequenced. The methylation status of cytosine was analyzed using Quma Program (26).

Cell surface marker analysis

Spleens were minced to make single cell suspension through a cell strainer (BD Biosciences). The cell suspension was stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4, CD8, CD11b and NK1.1 mAbs (BD Biosciences), respectively. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytosol and mitochondra fractionation

Cytosol and mitochondrion-enriched fractions were prepared essentially as previously described (27).

Western blotting analysis

Western boltting analysis was carried out as previously described (28). The blots were probed with the following antibodies: anti-IRF8 (C-19, Santa Cruz) at a 1:200 dilution; anti-mouse A-CDase (T-20, Santa Cruz) at 1:1000; anti-Cytochrome C (BD Biosciences) at 1:500; and anti-β-actin (Sigma, At Louis, MO) at 1:8000. Blots were detected using the ECL Plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) Western detection kit.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were carried out according to protocols from Upstate Biotech (Lake Placid, NY). Immuoprecipitation was carried out using anti-IRF8 antibody (C-19, Santa Cruz) and agarose-protein A beads (Upstate). The DNA was purified from the eluted solution and used for PCR. The PCR primers used to amplify region 5 of the acid ceramidase promoter (Fig 4B) are as follows: forward: 5′-TGTCGTCGAAGCAGAAAATG-3′, reverse, 5′-GTATTTGTCGCCGCGTTACT-3′.

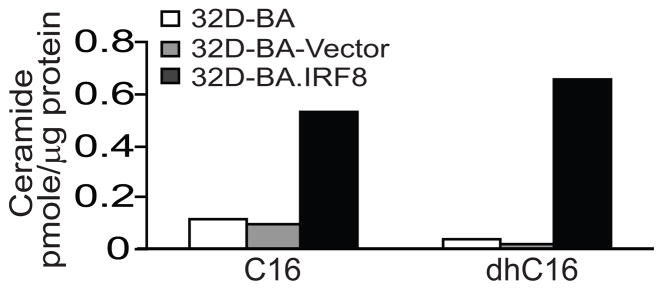

Figure 4. C16-ceramide and dhC16-ceramide contents in CML cells.

Ceramide contents were determined by LC/MS. Shown are representative results of two independent measurements.

Protein-DNA interaction assay

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) was carried out as previously described (25). The DNA probes are as follows: wt forward: 5 ′-GCCAGAGGAAAACTGGAAGTCCCGCCC-3 ′, reverse, 5 ′-GGGCGGGACTTCCAGTTTTCCTCTGGC-3′; mutant forward; 5 ′-GCCAGAGTCGTACTCTATGTCCCGCCC-3 ′, reverse: 5 ′-GGGCGGGACATAGAGTACGACTCTGGC-3′. Goat IgG and anti-IRF8 antibody (C-19) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotech.

Measurement of apoptotic cell death

Cells were treated with either IFN-γ (R&D Systems) overnight, acid ceramidase inhibitor LCL85 overnight, or C16 ceramide (Santa Cruz) for 1 h, followed by incubation with recombinant FasL (100 ng/ml, PeproTech; Rocky Hill, NJ) for approximately 24 h. Cells were then collected and incubated with propidium iodide (PI) solution (R&D Systems) and analyzed by flow cytometry. For measurement of apoptosis in CD11b+ primary cells, total spleen cells were treated with LCL85 (2 μM) for 4 h, followed by incubation with FasL (25 ng/ml) for approximately 16h. The cells were then collected and stained with anti-CD11b mAb (BD Biosciences) and PI. The CD11b+ cells were gated out to determine the percentage of PI+ CD11b+ cells. The percentage of cell death was calculated by the formula: % cell death=% PI+ cells after FasL treatment - % PI+ cells without FasL treatment.

Gene silencing

32D-BA cells were transduced with Scramble shRNA (Cat# sc-108080) and A-CDase-specific shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles (Cat# sc-140807-V, Santa Cruz) and selected for stable lines with puromycin. Cells were analyzed for A-CDase mRNA level by RT-PCR and sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis by PI staining as described above.

A-CDase overexpression

Mouse A-CDase coding region was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned to pEGFP-N1 plasmid to generated pEGFP.mA-CDase. The insert was verified by DNA sequence. 32D-BA.IRF8 cells were transiently transfected with pEGFP-N1 and pEGFP.mA-CDase, respectively, and analyzed for A-CDase expression by RT-PCR and sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis as described above.

Synthesis of LCL85

(1R,2R)-2_N-[16-(1′-pyridinium)-hexadecanoylamino)-1-(4′-nitrophenyl) -1,3-propandiol bromide, was synthesized by Lipidomics Shared Resource at Medical University of South Carolina, as previously described (29).

Measurement of endogenous ceramide level

Cellular levels of endogenous ceramides were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectroscopy (LC/MS) as described (30, 31). Ceramide levels were normalized to the total cellular protein contents.

Results

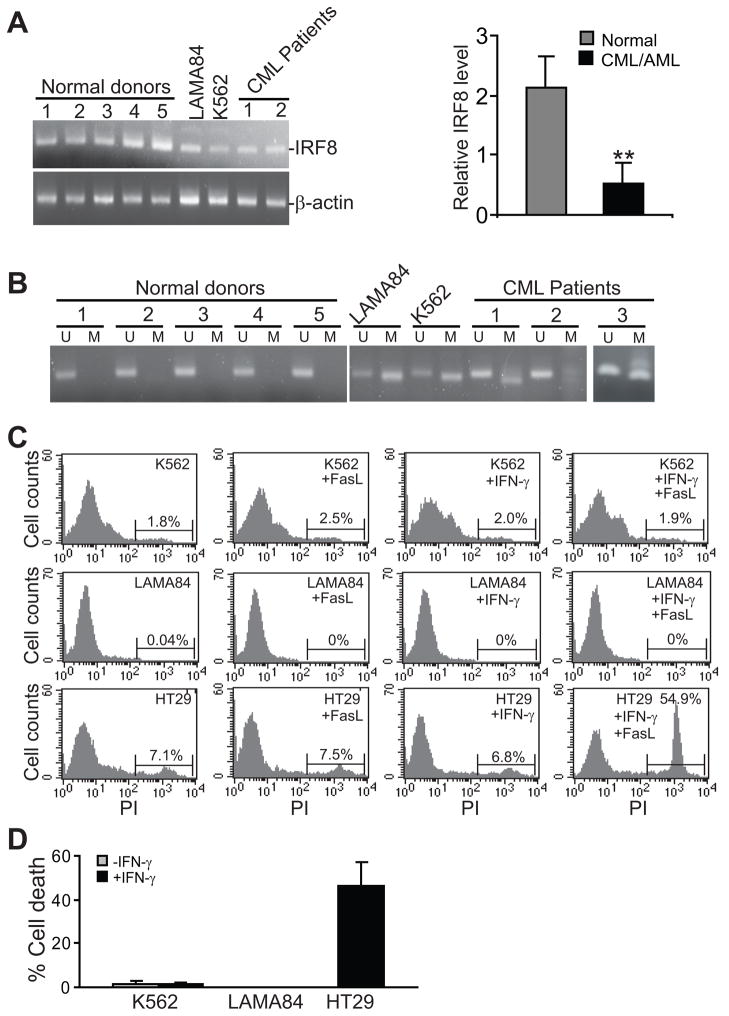

IRF8 expression is regulated by the IRF8 promoter DNA methylation in CML

IRF8 expression is dramatically down-regulated in the majority of human myeloid leukemia (11, 12). Because IRF8 expression is mediated by the IRF8 promoter DNA methylation in colon carcinoma cells (32) and multiple other types of tumors (33–36), we hypothesized that down-regulation of IRF8 might be mediated by the IRF8 promoter DNA methylation in human myeloid leukemia. To test this hypothesis, we first compared IRF8 expression level in human myeloid leukemia cell lines and patient PBMC to that in PBMC from normal donors. RT-PCR analysis indicated that IRF8 expression is indeed significantly lower in human myeloid leukemia cells than in normal PBMC cells as previously reported (11)(Figure 1A). MS-PCR analysis revealed that the IRF8 promoter is not methylated in normal human PBMC but methylated in human myeloid leukemia cell lines and PBMC derived from human myeloid leukemia patients (Figure 1B). Both myeloid leukemia cell lines K562 and LAMA84 exhibited a resistant phenotype to FasL-induced apoptosis (Figure 1C & D). It is known that IFN-γ can sensitized tumor cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis (37). However, IFN-γ treatment also failed to sensitize the two myeloid leukemia cell lines to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Figure 1C & D). Therefore, we concluded that human myeloid leukemia cells are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

Figure 1. IRF8 expression is mediated by the IRF8 promoter DNA methylation in human myeloid leukemia cells.

A. Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells or patient PBMC cells and used for IRF8 mRNA level by RT-PCR. The relative IRF8 mRNA level was expressed as the ratio of IRF8 band intensity over β-actin band intensity. The relative IRF8 level was then plotted as the mean of the 5 normal donors (normal) and CML/AML cell lines/patient specimens (right panel). Column: mean; Bar: SD. B. MS-PCR analysis of the human IRF8 promoter methylation. U:unmethylation, M: methylation. Specimen of CML patient 3 was analyzed in a different gel. C–D. Sensitivity of human CML/AML cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Human colon carcinoma cell HT29 was used as a positive control. The percent of FasL-induced cell death was then calculated by the formula: % cell death = % cell death in the presence of FasL - % cell death in the absence of FasL.

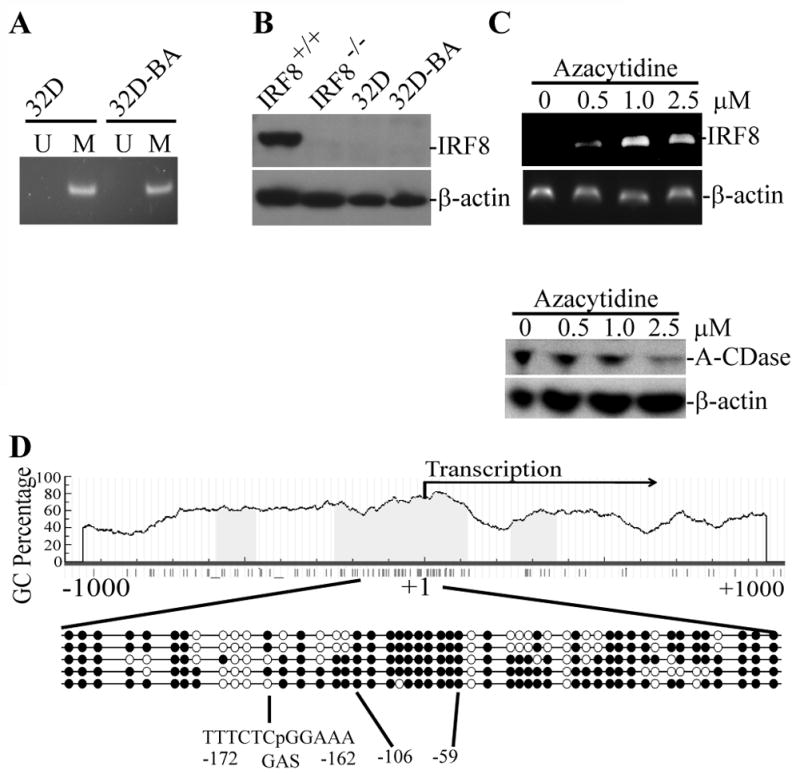

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying IRF8 promoter DNA methylation in myeloid leukemia pathogenesis, we used the myeloid 32Dcl (32D) progenitor cell model for in vitro and in vivo studies. To induce a Bcr/Abl dependent leukemia system, 32D cells were stably transfected with a vector containing the coding sequence of Bcr-Abl (32D-BA). The transfected cells thus mimic human myeloid leukemia. MS-PCR analysis revealed that the IRF8 promoter is methylated in 32D and 32D-BA cells (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the IRF8 promoter methylation status, IRF8 protein is undetectable in 32D and 32D-BA cells, and inhibition of DNA methylation restored IRF8 expression (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Methylation status of the IRF8 promoter in mouse CML cells.

A. Genomic DNA was isolated from 32D and 32D-BA cells and analyzed by MS-PCR for the IRF8 promoter methylation. U: unmethylation, M: methylation. B. Total lysate was prepared from myeloid cells differentiated in vitro from bone marrow of wt mice (IRF8+/+), IRF8 knock out mice (IRF8−/−), 32D and 32D-BA cells and analyzed for IRF8 protein level by Western blotting analysis. β-actin was used as normalization control. C. 32D-BA cells were treated with various concentrations of azacytidine for 3 days and analyzed for IRF8 expression by RT-PCR (top panel) and A-CDase protein level by Western blotting (bottom panel). D. Genomic DNA was isolated from 32D cells and modified with bisulfite sodium. The IRF8 promoter region as indicated was cloned and sequenced. The CpG islands were indicated by blue color. The transcription initiation site is marked by +1. Each circle represents a CpG dinucleotide. Open circle: unmethylated CpG; closed circle, methylated CpG. Results from 5 independent clones are shown.

We next cloned a 503 bp long IRF8 promoter region (−350 to + 153 relative to the IRF8 transcription initiation site) of 32D cells and sequenced the entire region. There are 51 CpG dinucleotides in this 503 bp region. Overall, an average of 73% of the cytosines of the 51 CpGs was methylation (Fig. 2D). GAS element is the binding site of IFN-γ-activated STAT1 (25). There is a GAS consensus sequence in the IRF8 promoter region (−162 to −172 relative to the IRF8 transcription initiation site). This GAS element contains a CpG (Fig. 2D). Only 3 of the 5 clones sequenced contain methylated cytosine inside this GAS element (Fig. 2D). An almost 100% methylated region is identified in all 5 clones analyzed in the region (−59 to −106 relative to the IRF8 transcription initiation site).

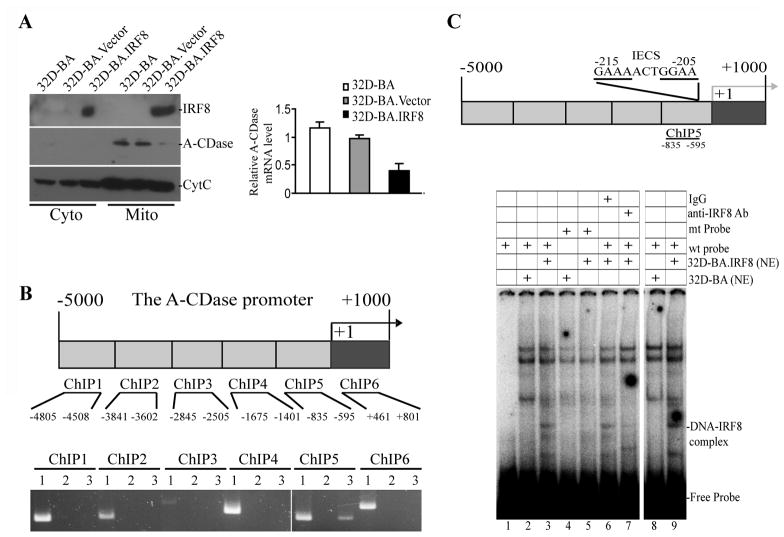

IRF8 is a transcription repressor of A-CDase in myeloid cells

We next restored IRF8 expression by ectopic expression of IRF8 in 32D-BA cells and analyzed the expression levels of key apoptosis mediators in the Fas-mediated apoptosis signaling pathway. Among the multiple apoptosis mediators examined, A-CDase was found to be repressed by ectopically expressed IRF8. A-CDase is present in the organelle-enriched mitochondrial fraction of 32D-BA and 32D-BA.Vector cells, but dramatically decreased in 32D.BA.IRF8 cells (Fig. 3A). The A-CDase transcript level is also significantly lower in 32D-BA.IRF8 cells as compared to the control cells (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the observation that inhibition of DNA methylation restores IRF8 expression (Fig. 2C), inhibition of DNA methylation repressed A-CDase expression (Fig. 2C).

Figure 3. IRF8 binds to the A-CDase promoter region to repress IRF8 expression in CML cells.

A. Cytosol and mitochondrion fractions were prepared from 32D-BA, 32D-BA.Vector and 32D.BA-IRF8 cells and analyzed for IRF8 and A-CDase protein level by Western blotting analysis. CytC was used as normalization control. Right panel: Analysis of A-CDase mRNA level by real-time PCR. B. ChIP analysis of IRF8 and A-CDase promoter interaction. Top panel: mouse A-CDase promoter structure. The ChIP PCR regions are indicated at the bottom. Bottom panel: ChIP PCR results. 1: input genomic DNA; 2. IgG control; 3. anti-IRF8 antibody. Shown is representative image of one of two independent experiments. C. IRF8 binds to the A-CDase promoter DNA in vitro. Top panel: The A-CDase promoter structure. Bottom panel: EMSA of IRF8 association with the IECS sequence-containing DNA probe. Nuclear extracts (NE) prepared from 32D-BA and 32D-BA.IRF8 cells were incubated with mutant probe (lanes 4 and 5), wt probe (lanes 1 2 3 6 7 8 and 9), in the presence of isotype control IgG (lane 6) or anti-IRF8 Ab (lanes 7), and analyzed for the DNA-protein interactions. Lanes 1–7: 5 μg nuclear extract/reaction. Lanes 8–9: 20 μg nuclear extract/reaction. The potential probe-IRF8 complex is indicated at the right.

To determine whether IRF8 directly regulates A-CDase transcription, we carried out ChIP assay to determine whether IRF8 directly binds to the A-CDase promoter region in vivo. Analysis of interactions between IRF8 protein and an approximately 6000 bp region of the A-CDase promoter (−5000 to +1000 relative to the A-CDase transcription initiation site) revealed that IRF8 binds to the A-CDase promoter near the transcription start site in 32D-BA.IRF8 cells (Fig. 3B). To locate the IRF8 binding site at the A-CDase promoter region, we analyzed the A-CDase promoter and identified a potential IRF8 binding site [IRF-Ets composite sequence (IECS)] (38) (Fig. 3C). Analysis of IRF8 and this IECS sequence interaction revealed that IRF8 specifically binds to this DNA sequence (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we concluded that IRF8 is a transcriptional repressor of A-CDase and IRF8 binds directly to the A-CDase promoter region to regulate A-CDase transcription in CML cells.

Restoration of IRF8 expression resulted in C16 ceramide accumulation in myeloid cells

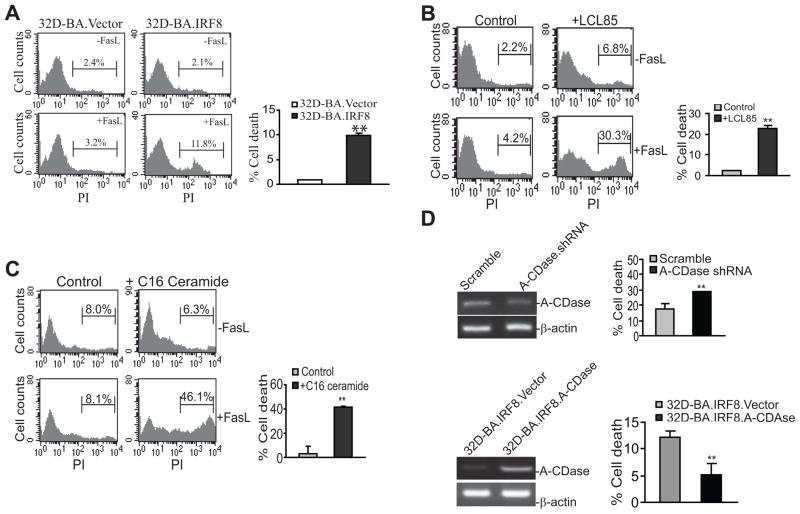

A-CDase converts ceramide to sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate and thus is a key mediator of the sphingosine signaling pathway (39, 40). We then measured C14- C16-, C18-, C20-, C22-, C24-, C26- and dhC16-ceramide contents in the 3 cell lines and found that these ceramide levels are very low to undetectable in 32D-BA and 32D-BA.Vector cells. Restoration of IRF8 significantly increased C16- and dhC16-ceramide levels (Fig. 4). Because accumulation of ceramide often increases cell sensitivity to apoptosis (30, 41, 42), we reasoned that 32D-BA.IRF8 cells should exhibit increased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Indeed, consistent with the increased ceramide level, 32D-BA.IRF8 cells became more sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. A-CDase mediates CML cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

A. Restoration of IRF8 expression sensitizes CML cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. 32D.Vector and 32D.IRF8 cells were cultured in the absence and presence of recombinant FasL for approximately 24 h and analyzed for apoptosis. Column, mean; Bar, SD. **p<0.01. Shown are representative results of one of three independent experiments. B. Inhibition of A-CDase activity increased CML cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. 32D-BA cells were either untreated (control) or treated with A-CDase inhibitor LCL85 overnight, followed by incubation with FasL for approximately 24 h and then analysis for apoptosis. Shown are representative images of three separate experiments. Column, mean; Bar, SD. ** p<0.01. C. Exogenous C16 ceramide increases CML cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. 32D-BA cells were cultured in the presence of C16 ceramide for 1 h, followed by incubation with FasL for approximately 16 h. Cell death was measured as in A. D. Silencing A-CDase or Overexpressing A-CDase alters CML cells sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Top panel: 32D-BA cells were transduced with lentivirus containing either scramble shRNA or A-CDase-specific shRNA. The cells were then analyzed for A-CDase silencing efficiency by RT-PCR (left panel) and sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis as described above in A. Shown are representative results of two independent experiments. Bottom panel: 32D-BA.IRF8 cells were transiently transfected with pEGFP vector or pEGFP-A-CDase and analyzed for A-CDase expression by RT-PCR (left panel) and sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (right panel) as described above in A. Shown are representative results of three independent experiments.

A-CDase mediates myeloid cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis

To further define the role of A-CDase in Fas-mediated apoptosis, we treated 32D-BA cells with A-CDase inhibitor LCL85. LCL85 represents a cationic analog of B13, the first discovered inhibitor of A-CDase, designed to act as mitochondriotropic inhibitor of this enzyme (29, 43). Pre-treatment with LCL85 significantly increased 32D-BA cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5B).

We also incubated 32D-BA cells with exogenous C16 ceramide and analyzed their sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. C16 ceramide pre-treatment significantly increased 32D-BA cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5C). In addition, silencing A-CDase also significantly increased 32D-BA cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5D). Conversely, overexpression of A-CDase significantly decreased 32D-BA cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5D). Taken together, we demonstrated, by four complementary approaches, that A-CDase plays an important role in mediating 32D-BA cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

IRF8 functions as an A-CDase transcription repressor to regulate primary myeloid cell lineage differentiation in vivo

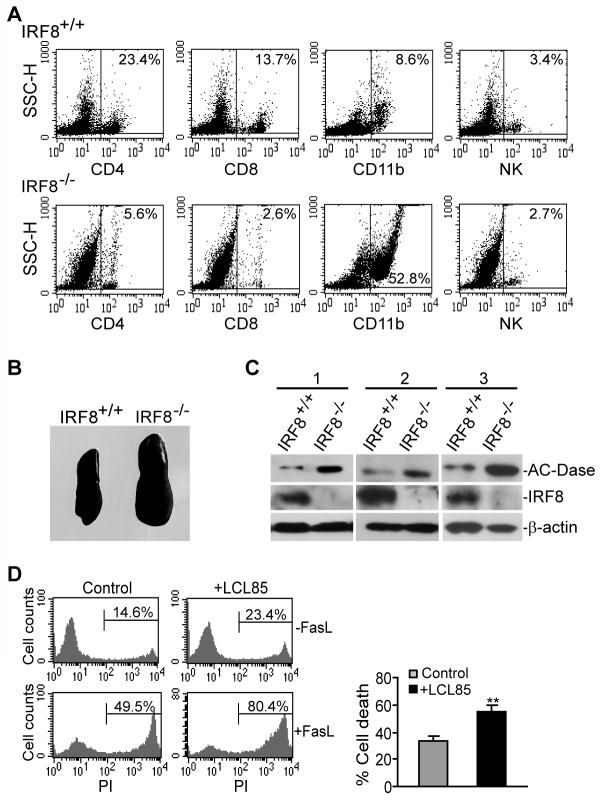

To determine whether IRF8 regulates A-CDase expression under physiological conditions, we examined A-CDase protein level in IRF8 knock out mice. Spleen cells from IRF8 knock out and age-matched wt control littermate mice were first analyzed for 4 major subsets of immune cells: CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD11b+ macrophage and NK cells. As compared to the wt mice, the percentage of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NK cells were decreased in spleens from IRF8 knock out mice. However, the total number of T and NK cells per spleen is similar between IRF8 knockout and wild type mice. As noted before, the size of spleen of the IRF8 knock out mice was larger than that of wt mice (Fig. 6B). CD11b+ cells that likely include macrophages and granulocytes were increased in the spleen of the IRF8 knock out mice (Fig. 6A), thus confirming the role of IRF8 as a key transcription factor in lineage-specific differentiation of myeloid cells (1, 2). Analysis of A-CDase level revealed that A-CDase protein level is weak to undetectable in CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NK cells and knocking out IRF8 did not alter AC-Dase protein level in these 3 subsets of primary cells. However, A-CDase protein level is dramatically higher in CD11b+ cells in IRF8 knock out mice than that in control mice (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Myeloid cells of IRF8-deficient mice exhibited increased A-CDase protein level.

A. Single cell suspension was prepared from spleens of IRF8 knock out and age-matched wt littermate control mice, and analyzed for CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD11b+ myeloid cells and NK cells. Number in the box indicates the percentage of that particular cell subset. Shown are representative data from one of 3 pairs of mice. B. Spleens of IRF8+/+ and IRF8−/− mice. C. CD11b+ cells were isolated from spleens of 3 age-matched pairs of IRF8+/+ and IRF8−/− mice and used for total lysate preparation. The total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting analysis for A-CDase protein level. D. Inhibition of A-CDase activity increases myeloid cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Single cell suspension was prepared from spleens of IRF8 knock out mice. Cells were incubated with LCL85 for 4 h, followed by incubation with FasL for approximately 16 h. The cells were then stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD11b mAb and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD11b+ cells were gated to determine the PI+ cells. Shown are representative results of one of 3 independent experiments. Column, mean; Bar, SD.

Next, we sought to determine whether inhibiting A-CDase increases the sensitivity of the IRF8 KO CD11b+ cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Spleen cells were pretreated with LCL85 and then incubated with FasL. The primary IRF8 KO CD11b+ cells are sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 6D). However, LCL85 significantly increased the IRF8 KO CD11b+ cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 6D). Taken together, our data suggest that IRF8 regulates myeloid cell lineage differentiation at least partially through regulating apoptosis sensitivity in an A-CDase-dependent manner.

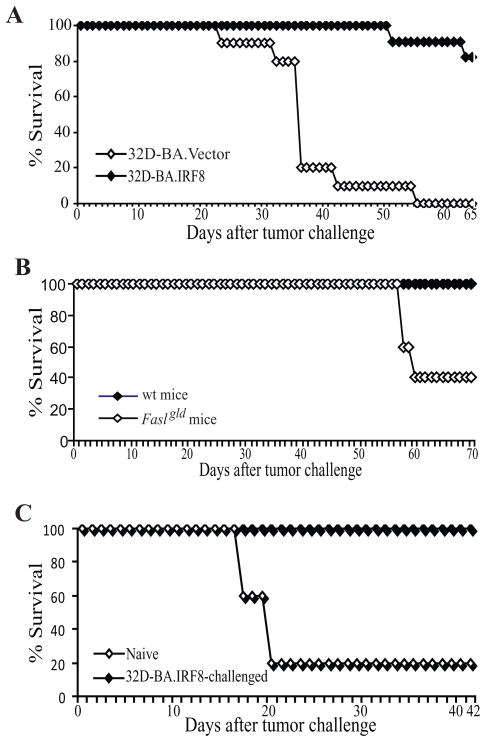

IRF8 suppresses CML development in vivo

Because IRF8 represses A-CDase expression to mediate apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells (Fig. 5), we next tested whether restoration of IRF8 expression would suppress myeloid leukemia development in vivo. 32D-BA.Vector and 32D-BA.IRF8 cells were injected into naïve mice and mouse survival was recorded. Mice that received 32D-BA.Vector cells started to die on day 24 after tumor transplant and all mice were dead 56 days after tumor transplant. In contrast, only one of the 11 mice that received 32D-BA.IRF8 cells was dead 52 days after tumor transplant and 9 of the 11 mice were still alive 65 days after tumor transplant (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. The Fas-mediated effector mechanism of the host immune system plays an important role in suppression of myeloid leukemia development.

A. Restoration of IRF8 expression increased the survival tumor-bearing mice. 32D-BA.Vector and 32D-BA.IRF8 cells (1×106/mouse) were injected to naïve mice (n=10 for 32D-BA.Vector cells, n=11 for 32D-BA.IRF8 cells) i.v. and mouse survival was recorded over time. The survival rate was plotted against days after tumor cell transplant. B. FasL-deficient mice exhibited significant lower survival rate after tumor challenge. 32D-BA.IRF8 cells (1×106/mouse) were injected to wt (n=5) and FasL-deficient (Faslgld) mice (n=5) i.v. and mouse survival was recorded over time. The survival rate was plotted against days after tumor cell transplant. C. Immunologic memory against myeloid leukemia. Naïve mice and mice that were injected with 32D-BA.IRF8 cells and survived as shown in A were re-challenged with 32D-BA cells 90 days after the first tumor injection, and observed for survival. The survival rate was plotted against days after tumor cell transplant.

Fas-mediated apoptosis pathway is a key effector mechanism for the host immune system to eliminate unwanted or diseased cells to maintain normal homeostasis (44) and to control tumor development (45, 46). It has been shown that the host T lymphocytes play a key role in suppressing myeloid leukemia (47). T lymphocytes primarily use perforin and FasL to induce target tumor cell apoptosis (46, 48). Therefore, acquisition of resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis may confer the tumor cell an advantage to avoid the T lymphocyte-mediated elimination. Our above observations that restoration of IRF8 expression confers the tumor cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5A) and immune-competent naïve mice can survive 32D-BA.IRF8 tumor cell challenge (Fig. 7A) suggest that the host immune cells might have played a significant role in suppressing apoptosis-sensitive myeloid leukemia development through the Fas-mediated effector mechanism. In that case, we expected that 32D-BA.IRF8 cells should cause increased mortality in the FasL-deficient mice. Indeed, FasL-deficient mice exhibited significantly lower survival rate than the wt control mice after 32D-BA.IRF8 tumor cell challenge (Fig. 7B).

Immune-competent mice can survive 32D-BA.IRF8 cell challenge (Fig. 7A). To determine whether the surviving mice would develop immunological memory against myeloid leukemia, we re-challenged these surviving mice with 32D-BA cells 90 days after the first tumor challenge. Naïve mice were used as control. While naïve mice receiving this first 32D-BA cell injection died all up to 43 days after transplantation, all of the 32D-BA.IRF8 cell pre-challenged mice remained alive at the end of the experiment (56 days after the tumor challenge) (Fig. 7C). Taken together, our data suggest that IRF8 functions as a tumor suppressor at least partially through regulating A-CDase expression to mediate CML sensitivity to Fas-mediated effector mechanism of the host immune system in vivo.

Discussion

Human myeloid leukemia patients exhibited significant decreased level of IRF8 protein in their hematopoietic cells (11, 12). A major phenotype of IRF8 knock out mice is the uncontrolled clonal expansion of granulocytes and macrophages that can progress to a fatal blast crisis (2). These observations suggest that IRF8 is a tumor suppressor. It has been proposed that acquisition of apoptosis resistance is responsible for the CML-like pathogenesis, and several apoptosis regulator, including Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and FAP-1, have been shown to play a role in regulating apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells in vitro (15, 18, 19). The function of IRF8 in apoptosis and tumor suppression has also been demonstrated in other non-hematopoietic cells (27, 32, 37, 49). However, it has been shown that the correlation between IRF8 and the Bcl-2 family members observed in vitro is not observed in vivo (21). Our data suggest that IRF8 is a transcription repressor of A-CDase in myeloid leukemia cells in vitro and in primary myeloid cells in vivo.

A-CDase converts ceramide to sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate and thus is a key mediator of the sphingosine signaling pathway, which plays a key role in Fas-mediated apoptosis (39, 40). We demonstrated here, by four complementary approaches, that A-CDase directly mediates Fas-mediated apoptosis in CML cells (Fig. 5). Our data also revealed that IRF8 directly binds to the A-CDase promoter to repress IRF8 expression (Figs. 3B&C). Furthermore, restoration of IRF8 expression in myeloid leukemia cells decreased A-CDase protein level (Fig. 3A) and consequently led to accumulation of C16 ceramide (Fig. 4). C16 ceramide has been shown to protect HNSCC cells from ER stress and apoptosis (50). However, C16 ceramide has also been shown to increase the sensitivity of Jurkat T cells and hepatocytes to Fas-mediated apoptosis (41). Our data suggest that C16 ceramide enhances CML sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5). More importantly, we demonstrated that IRF8 also represses A-CDase expression in primary myeloid cells in vivo. Thus, our data strong suggest that IRF8 functions as an apoptosis mediator at least partially through repressing A-CDase transcription in myeloid cells.

The lymphocyte-executed and Fas-mediated apoptosis is a key effector mechanism for the host immune system to eliminate unwanted and/or diseased cells during linage differentiation and homeostasis (44). The Fas-mediated apoptosis is also a critical component of the host immunosurveillance system in suppression of tumor development (45, 46). It has been shown that the host T lymphocytes play a key role in suppressing myeloid leukemia (47). We observed that restoration of IRF8 expression suppressed myeloid leukemia development in vivo (Fig. 7A). We further observed that IRF8-mediated tumor suppression function is significantly impaired in FasL-deficient mice. Based on these observations, we propose that the Fas-mediated effector mechanism of the host T lymphocytes plays an important role in the elimination of unwanted cells during myeloid cell linage differentiation to maintain normal homeostasis. IRF8 regulates A-CDase and potentially other apoptosis-related genes (15, 18–21) to maintain myeloid cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis for normal homeostasis. Loss of IRF8 expression (i.e. via the IRF8 promoter DNA methylation) leads to increased A-CDase, decreased C16 ceramide, and subsequently an apoptosis resistant phenotype, resulting in uncontrolled clonal expansion of undifferentiated myeloid cells that can progress to CML.

Acknowledgments

Grant support from the National Institutes of Health (CA133085 to K.L), the American Cancer Society (RSG-09-209-01-TBG to K.L.)

References

- 1.Tamura T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Shmeltzer Z, Kuwata T, Ozato K. ICSBP directs bipotential myeloid progenitor cells to differentiate into mature macrophages. Immunity. 2000;13(2):155–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtschke T, Lohler J, Kanno Y, et al. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87(2):307–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwieger M, Lohler J, Friel J, Scheller M, Horak I, Stocking C. AML1-ETO inhibits maturation of multiple lymphohematopoietic lineages and induces myeloblast transformation in synergy with ICSBP deficiency. J Exp Med. 2002;196(9):1227–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hao SX, Ren R. Expression of interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP) is downregulated in Bcr-Abl-induced murine chronic myelogenous leukemia-like disease, and forced coexpression of ICSBP inhibits Bcr-Abl-induced myeloproliferative disorder. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(4):1149–61. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1149-1161.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dror N, Rave-Harel N, Burchert A, et al. Interferon Regulatory Factor-8 Is Indispensable for the Expression of Promyelocytic Leukemia and the Formation of Nuclear Bodies in Myeloid Cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5633–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levi BZ, Hashmueli S, Gleit-Kielmanowicz M, Azriel A, Meraro D. ICSBP/IRF-8 transactivation: a tale of protein-protein interaction. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22(1):153–60. doi: 10.1089/107999002753452764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter-Koltunoff M, Goren S, Nousbeck J, et al. Innate immunity to intraphagosomal pathogens is mediated by interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF-8) that stimulates the expression of macrophage-specific Nramp1 through antagonizing repression by c-Myc. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(5):2724–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tailor P, Tamura T, Morse HC, 3rd, Ozato K. The BXH2 mutation in IRF8 differentially impairs dendritic cell subset development in the mouse. Blood. 2008;111(4):1942–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Qian X, Ning H, Yang J, Xiong H, Liu J. Activation of IL-27 p28 gene transcription by interferon regulatory factor 8 in cooperation with interferon regulatory factor1. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saberwal G, Horvath E, Hu L, Zhu C, Hjort E, Eklund EA. The interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP/IRF8) activates transcription of the FANCF gene during myeloid differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(48):33242–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt M, Nagel S, Proba J, et al. Lack of interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP) transcripts in human myeloid leukemias. Blood. 1998;91(1):22–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Blanco E, Bruns I, Neumann F, et al. Molecular signature of CD34(+) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells of patients with CML in chronic phase. Leukemia. 2007;21(3):494–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turcotte K, Gauthier S, Tuite A, Mullick A, Malo D, Gros P. A mutation in the Icsbp1 gene causes susceptibility to infection and a chronic myeloid leukemia-like syndrome in BXH-2 mice. J Exp Med. 2005;201(6):881–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurevich RM, Rosten PM, Schwieger M, Stocking C, Humphries RK. Retroviral integration site analysis identifies ICSBP as a collaborating tumor suppressor gene in NUP98-TOP1-induced leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(9):1192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burchert A, Cai D, Hofbauer LC, et al. Interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP; IRF-8) antagonizes BCR/ABL and down-regulates bcl-2. Blood. 2004;103(9):3480–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt M, Bies J, Tamura T, Ozato K, Wolff L. The interferon regulatory factor ICSBP/IRF-8 in combination with PU.1 up-regulates expression of tumor suppressor p15(Ink4b) in murine myeloid cells. Blood. 2004;103(11):4142–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardi V, Naveiras O, Azam M, Daley GQ. ICSBP-mediated immune protection against BCR-ABL-induced leukemia requires the CCL6 and CCL9 chemokines. Blood. 2009;113(16):3813–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabriele L, Phung J, Fukumoto J, et al. Regulation of apoptosis in myeloid cells by interferon consensus sequence-binding protein. J Exp Med. 1999;190(3):411–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang W, Zhu C, Wang H, Horvath E, Eklund EA. The interferon consensus sequence-binding protein (ICSBP/IRF8) represses PTPN13 gene transcription in differentiating myeloid cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7921–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Middleton MK, Zukas AM, Rubinstein T, et al. Identification of 12/15-lipoxygenase as a suppressor of myeloproliferative disease. J Exp Med. 2006;203(11):2529–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenigsmann J, Carstanjen D. Loss of Irf8 does not co-operate with overexpression of BCL-2 in the induction of leukemias in vivo. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(12):2078–82. doi: 10.3109/10428190903296913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koenigsmann J, Rudolph C, Sander S, et al. Nf1 haploinsufficiency and Icsbp deficiency synergize in the development of leukemias. Blood. 2009;113(19):4690–701. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konieczna I, Horvath E, Wang H, et al. Constitutive activation of SHP2 in mice cooperates with ICSBP deficiency to accelerate progression to acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(3):853–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI33742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang D, Ud Din N, Browning DD, Abrams SI, Liu K. Targeting lymphotoxin beta receptor with tumor-specific T lymphocytes for tumor regression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):5202–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGough JM, Yang D, Huang S, et al. DNA methylation represses IFN-gamma-induced and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-mediated IFN regulatory factor 8 activation in colon carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(12):1841–51. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumaki Y, Oda M, Okano M. QUMA: quantification tool for methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W170–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang D, Wang S, Brooks C, et al. IFN regulatory factor 8 sensitizes soft tissue sarcoma cells to death receptor-initiated apoptosis via repression of FLICE-like protein expression. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):1080–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang D, Stewart TJ, Smith KK, Georgi D, Abrams SI, Liu K. Downregulation of IFN-γR in association with loss of Fas function is linked to tumor progression. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(2):350–62. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szulc ZM, Mayroo N, Bai A, et al. Novel analogs of D-e-MAPP and B13. Part 1: synthesis and evaluation as potential anticancer agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(2):1015–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baran Y, Salas A, Senkal CE, et al. Alterations of ceramide/sphingosine 1-phosphate rheostat involved in the regulation of resistance to imatinib-induced apoptosis in K562 human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(15):10922–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bielawski J, Pierce JS, Snider J, Rembiesa B, Szulc ZM, Bielawska A. Comprehensive quantitative analysis of bioactive sphingolipids by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;579:443–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-322-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang D, Thangaraju M, Greeneltch K, et al. Repression of IFN regulatory factor 8 by DNA methylation is a molecular determinant of apoptotic resistance and metastatic phenotype in metastatic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3301–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KY, Geng H, Ng KM, et al. Epigenetic disruption of interferon-gamma response through silencing the tumor suppressor interferon regulatory factor 8 in nasopharyngeal, esophageal and multiple other carcinomas. Oncogene. 2008;27(39):5267–76. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, Ren S, Howell P, Fodstad O, Riker AI. Identification of novel epigenetically modified genes in human melanoma via promoter methylation gene profiling. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008;21(5):545–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tshuikina M, Jernberg-Wiklund H, Nilsson K, Oberg F. Epigenetic silencing of the interferon regulatory factor ICSBP/IRF8 in human multiple myeloma. Exp Hematol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tshuikina M, Nilsson K, Oberg F. Positive histone marks are associated with active transcription from a methylated ICSBP/IRF8 gene. Gene. 2008;410(2):259–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang D, Thangaraju M, Browning DD, et al. IFN Regulatory Factor 8 Mediates Apoptosis in Nonhemopoietic Tumor Cells via Regulation of Fas Expression. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4775–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanno Y, Levi BZ, Tamura T, Ozato K. Immune cell-specific amplification of interferon signaling by the IRF-4/8-PU.1 complex. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25(12):770–9. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paris F, Grassme H, Cremesti A, et al. Natural ceramide reverses Fas resistance of acid sphingomyelinase(−/−) hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(11):8297–305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rotolo JA, Zhang J, Donepudi M, Lee H, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R. Caspase-dependent and -independent activation of acid sphingomyelinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(28):26425–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cremesti A, Paris F, Grassme H, et al. Ceramide enables Fas to cap and kill. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(26):23954–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Elojeimy S, Turner LS, et al. Acid ceramidase inhibition: a novel target for cancer therapy. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2293–8. doi: 10.2741/2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bielawska A, Bielawski J, Szulc ZM, et al. Novel analogs of D-e-MAPP and B13. Part 2: signature effects on bioactive sphingolipids. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(2):1032–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegel RM, Chan FK, Chun HJ, Lenardo MJ. The multifaceted role of Fas signaling in immune cell homeostasis and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(6):469–74. doi: 10.1038/82712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caldwell SA, Ryan MH, McDuffie E, Abrams SI. The Fas/Fas ligand pathway is important for optimal tumor regression in a mouse model of CTL adoptive immunotherapy of experimental CMS4 lung metastases. J Immunol. 2003;171(5):2402–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seki N, Brooks AD, Carter CR, et al. Tumor-specific CTL kill murine renal cancer cells using both perforin and Fas ligand-mediated lysis in vitro, but cause tumor regression in vivo in the absence of perforin. J Immunol. 2002;168(7):3484–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng M, Daley GQ. Expression of interferon consensus sequence binding protein induces potent immunity against BCR/ABL-induced leukemia. Blood. 2001;97(11):3491–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kagi D, Vignaux F, Ledermann B, et al. Fas and perforin pathways as major mechanisms of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Science. 1994;265(5171):528–30. doi: 10.1126/science.7518614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Egwuagu CE, Li W, Yu CR, et al. Interferon-gamma induces regression of epithelial cell carcinoma: critical roles of IRF-1 and ICSBP transcription factors. Oncogene. 2006;25(26):3670–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senkal CE, Ponnusamy S, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Ogretmen B. Antiapoptotic roles of ceramide-synthase-6-generated C16-ceramide via selective regulation of the ATF6/CHOP arm of ER-stress-response pathways. Faseb J. 2010;24(1):296–308. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]