Abstract

Diatoms survive in dark, anoxic sediment layers for months to decades. Our investigation reveals a correlation between the dark survival potential of marine diatoms and their ability to accumulate NO3− intracellularly. Axenic strains of benthic and pelagic diatoms that stored 11–274 mM NO3− in their cells survived for 6–28 wk. After sudden shifts to dark, anoxic conditions, the benthic diatom Amphora coffeaeformis consumed 84–87% of its intracellular NO3− pool within 1 d. A stable-isotope labeling experiment proved that 15NO3− consumption was accompanied by the production and release of 15NH4+, indicating dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA). DNRA is an anaerobic respiration process that is known mainly from prokaryotic organisms, and here shown as dissimilatory nitrate reduction pathway used by a eukaryotic phototroph. Similar to large sulfur bacteria and benthic foraminifera, diatoms may respire intracellular NO3− in sediment layers without O2 and NO3−. The rapid depletion of the intracellular NO3− storage, however, implies that diatoms use DNRA to enter a resting stage for long-term survival. Assuming that pelagic diatoms are also capable of DNRA, senescing diatoms that sink through oxygen-deficient water layers may be a significant NH4+ source for anammox, the prevalent nitrogen loss pathway of oceanic oxygen minimum zones.

Keywords: eukaryotic microbiology, marine ecology, N-cycle, nitrate ammonification, microalgae

Diatoms are eukaryotic phototrophs that are ubiquitous in both the pelagic and benthic zones of aquatic ecosystems. Approximately 40% of marine primary production is due to diatoms, making them key players in the global carbon cycle (1). Many diatoms take up and store NO3− intracellularly in concentrations of up to a few 100 mM (2–4), which exceeds ambient NO3− concentrations by several orders of magnitude. It is well documented that diatoms use intracellular NO3− for assimilatory NO3− reduction (2); however, the intracellular NO3− pool also might be used for dissimilatory NO3− reduction.

Mass sinking of pelagic diatom blooms is triggered by nutrient depletion in the surface layer of the water column (5). However, silicate depletion, not nitrate depletion, is the prevalent environmental cue for increased sinking rates (6). Therefore, the intracellular NO3− pool might not be depleted in diatoms that sink from the nutrient-poor surface layer to nutrient-rich deeper layers or the sediment surface. In fact, Lomstein et al. (7) found high intracellular NO3− pools in phytoplankton freshly deposited on the seafloor. A considerable fraction of the settled diatoms survive for months to decades as vegetative or resting cells in dark, anoxic sediment layers, in which neither photosynthesis nor aerobic respiration can occur (8–10). Benthic diatoms experience shifts to dark, anoxic conditions due to vertical migration behavior in the sediment (11) and burial by bioturbating animals (12). The occurrence of NO3−-storing diatoms in deep sediment layers increases the concentration of cell-bound NO3−, which has potential implications for nitrogen cycling (7, 13–15). However, the energy-providing metabolism that allows diatoms to survive in dark, anoxic sediments is not known, and the fate of the intracellular NO3− is unclear.

Dissimilatory NO3− reduction is common in many anaerobic prokaryotes, and was recently found in several eukaryotic taxa as well. The anaerobic protozoan Loxodes spp. respires NO3− to NO2− (16), and the two fungi Fusarium oxysporum and Cylindrocarpon tonkinense respire NO3− to N2O (17, 18). Complete denitrification of NO3− to N2 has been reported for NO3−-storing benthic foraminiferans (19, 20). Dissimilatory NO3− reduction also can lead to NH4+ formation in a pathway known as dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA), a process well documented in prokaryotes, such as large sulfur bacteria (21, 22). The only eukaryotes known to be capable of DNRA are fungi (23, 24). DNRA is involved in anaerobic energy generation via a two-step reaction sequence: NO3− reduction to NO2− is coupled to electron transport phosphorylation, whereas NO2− reduction to NH4+ is coupled to substrate-level phosphorylation (25). The second reduction step has only a small ATP yield and can thus be considered an electron sink that serves to regenerate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (26).

We hypothesize that dissimilatory NO3− reduction is a metabolism used by diatoms to survive darkness and anoxia. To test this hypothesis, we anexically cultured three pelagic and three benthic diatom strains to investigate the maximum storage capacity for intracellular NO3− and the correlation between the intracellular NO3− concentration and survival in darkness and anoxia. We further investigated the benthic diatom A. coffeaeformis with respect to the consumption of intracellularly stored NO3− after a sudden shift to dark/anoxic conditions and the production of intermediates and end products of denitrification and DNRA.

Results

Intracellular NO3− Accumulation.

The maximum intracellular NO3− concentrations reached during cultivation of diatom strains under optimal conditions (i.e., availability of light, O2, and nutrients) ranged from 0.4 mM (for Cylindrotheca closterium) to 274 mM (for A. coffeaeformis) (Table 1). The lack of substantial intracellular NO3− storage in C. closterium might have resulted from competition with bacteria contaminating the culture. The maximum intracellular NO3− concentration was not correlated with the habitat type of the different diatom species (pelagic or benthic). The residual NO3− concentrations in the growth medium at the time of cell harvesting were always lower than the intracellular NO3− concentrations (Table 1). The resulting enrichment factors (i.e., intracellular over extracellular NO3− concentration) ranged from 5 (for Ditylum brightwellii) to 391 (for A. coffeaeformis; Table 1). The maximum intracellular NO3− contents were not correlated with the cell volume (Table 1); that is, large diatom cells generally did not store more NO3− than small cells.

Table 1.

Intracellular NO3− accumulation in cultures of six diatom species from benthic and pelagic habitats

| Species name | Habitat type | Maximum intracellular NO3− content, fmol* | Cell volume, pL | Maximum intracellular NO3− concentration, mM† | NO3− concentration in growth medium, mM‡ | Enrichment factor |

| D. brightwellii | Pelagic | 111.6 (32.2) | 24.80 | 4.5 (1.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) |

| S. costatum | Pelagic | 3.7 | 0.33 | 11.1 | 0.1 | 111 |

| T. weissflogii | Pelagic | 113.1 (6.7) | 1.22 | 92.9 (5.5) | 0.9 (0.1) | 103 (5.4) |

| C. closterium | Benthic | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.4 | < 0.1 | NA |

| N. punctata | Benthic | 4.5 (0.3) | 0.11 | 40.6 (2.5) | 0.9 (0.1) | 45 (2.2) |

| A. coffeaeformis | Benthic | 128.8 (41.1) | 0.47 | 273.7 (87.4) | 0.7 (0.1) | 391 (69.0) |

NA, not applicable.

*Maximum intracellular NO3− content reached during cultivation under light/oxic conditions. Values are mean (SD) of three replicate culture tubes; S. costatum and C. closterium were analyzed only once.

†Calculated from maximum intracellular NO3− content and cell volume.

‡Measured at the time of cell harvesting for analysis of intracellular NO3− content.

Survival Under Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

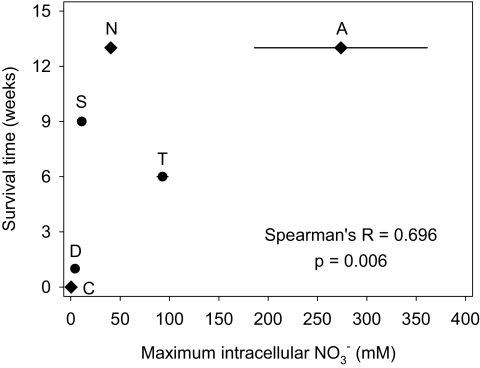

The maximum time of surviving dark/anoxic conditions was significantly positively correlated with the maximum intracellular NO3− concentration in the various diatom species (Fig. 1). In contrast, survival time was not correlated with the habitat of the diatom species. In single culture tubes of Nitzschia punctata and A. coffeaeformis, a maximum survival time of 28 wk was recorded. Cell counts did not reveal growth in any of the six tested diatom species incubated under dark/anoxic conditions. In contrast, all six species were actively growing before the start of the survival experiment.

Fig. 1.

Correlation between maximum intracellular NO3− concentration and survival time under dark/anoxic conditions in the diatom species D. brightwellii (D), S. costatum (S), T. weissflogii (T), C. closterium (C), N. punctata (N), and A. coffeaeformis (A). Circles denote pelagic species, diamonds denote benthic species. Values are mean concentration ± SD of three replicates; Spearman's R and probability P for nonlinear correlations are given.

Consumption of Intracellular NO3− in Response to Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

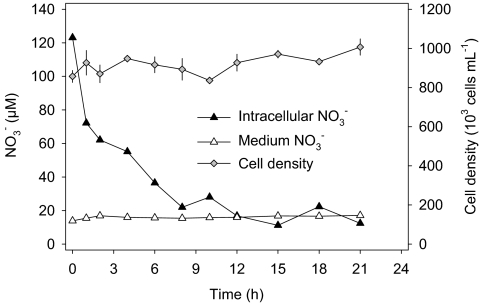

Intracellular NO3− was rapidly consumed in response to dark/anoxic conditions, with much of the consumption occurring during the first 8 h of the experiment (Fig. 2). Within 21 h of the experiment, 87% of the intracellular NO3− was consumed. The stable NO3− concentration in the growth medium indicated that intracellular NO3− was indeed consumed by A. coffeaeformis rather than lost to the growth medium (Fig. 2). The axenic A. coffeaeformis culture did not grow under dark/anoxic conditions (Fig. 2), whereas the culture was actively growing before the experiment.

Fig. 2.

Consumption of intracellular NO3− (expressed in μmol/L of growth medium) in an axenic A. coffeaeformis culture in response to dark/anoxic conditions. Time courses of NO3− concentration in the growth medium and of the mean cell density (± SE of four repeated counts) are also shown. Dark/anoxic conditions were initiated at 0 h.

Dissimilatory NO3− Reduction in Response to Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

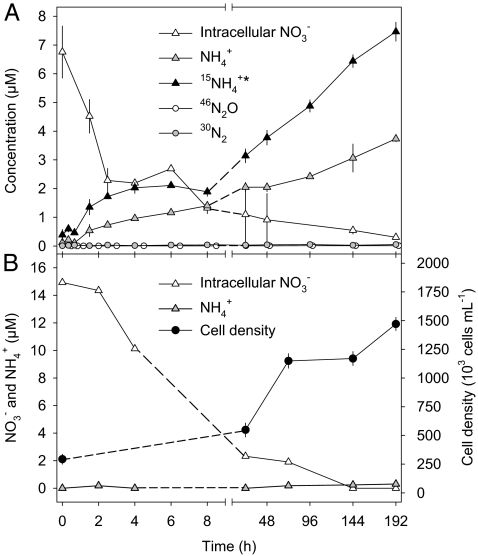

Axenic A. coffeaeformis cultures grown under light/oxic conditions with 1 mM 15NO3− or 14NO3− were harvested, washed, and transferred into NO3−-free artificial seawater enriched with 200 μM Na-acetate as an electron donor. Thus, for the subsequent experiments, the sole NO3− source was intracellularly stored 15NO3− or 14NO3−. Initial intracellular NO3− concentrations and cell densities differed slightly between the two pretreatments. When exposed to dark/anoxic conditions, axenic A. coffeaeformis cultures simultaneously consumed intracellular NO3− and produced NH4+ that was released into the growth medium (Fig. 3A). In contrast, when exposed to light/oxic conditions, axenic A. coffeaeformis cultures also consumed intracellular NO3−, but did not release NH4+ (Fig. 3B). A. coffeaeformis cultures exposed to light/oxic conditions were growing (Fig. 3B), whereas those exposed to dark/anoxic conditions were not (Fig. 2). Thus, the intracellular NO3− pool is used for assimilation during growth conditions and energy generation under dark/anoxic conditions. The production of 46N2O and 30N2 from intracellular 15NO3− under dark/anoxic conditions was negligible (Fig. 3A and Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Time course of N compounds in an axenic A. coffeaeformis culture in response to dark/anoxic conditions (A) and light/oxic conditions (B). Cells were preincubated with 15NO3− (A) or 14NO3− (B) in the growth medium under light/oxic conditions. Experimental conditions were initiated at 0 h. 15NH4+* denotes isotopically labeled N compounds measured with the hypobromite assay. Intracellular NO3− concentrations are expressed in μmol/L of growth medium. Values are mean ± SD of three replicate culture tubes are shown.

Table 2.

Cell-specific rates of N conversion by axenic A. coffeaeformis cultures in response to different experimental conditions

| Experimental conditions | Time interval | NO3− consumption, fmol cell−1 h−1 | NH4+ production, fmol cell−1 h−1 | 15NH4+* production, fmol cell−1 h−1 | 46N2O production, fmol cell−1 h−1 | 30N2 production, fmol cell−1 h−1 |

| Dark/anoxic | 0–2.5 h | −9.123 (2.631) | 1.365 (0.394) | 2.958 (0.853) | 0.007 (0.002) | 0.025 (0.007) |

| 8–192 h | −0.027 (0.008) | 0.058 (0.017) | 0.148 (0.043) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Light/oxic | 0–2.5 h | −4.101 (0.602) | <0.001 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8–192 h | −0.016 (0.002) | 0.001 | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not determined.

Rates were calculated from the time course of N compounds presented in Fig. 3 for the linear changes in concentration between 0 and 2.5 h and between 8 and 192 h of incubation. Cell densities were 194 ± 56 × 103 cells mL−1 (0–192 h) in the dark/anoxic incubation and 293 ± 43 (0–2.5 h) and 1,263 ± 163 × 103 cells mL−1 (8–192 h) in the light/oxic incubation. Values are mean (SD) for rates >0.001 fmol cell−1 h−1.

The rates of simultaneous NO3− consumption and NH4+ production under dark/anoxic conditions were higher in the early phase of the experiment (0–2.5 h) than in the late phase (8–192 h) (Table 2). Within 24 h of dark/anoxic incubation, 84% of the intracellular NO3− was consumed (Fig. 3A). Axenic A. coffeaeformis cultures preincubated with 15NO3− released 15NH4+* into the growth medium at about twice the rate of NH4+ release (Fig. 3A and Table 2). 15NH4+* denotes isotopically labeled N compounds measured with the hypobromite assay (see Materials and Methods for details). At the end of the experiment, the total amounts of NH4+ and 15NH4+* released corresponded to 56% ± 5% and 110% ± 10%, respectively, of the total amount of intracellular NO3− consumed (calculated from data presented in Fig. 3A).

Discussion

Intracellular NO3− Aids Survival of Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

Viable diatom cells are buried in sediments at depths in which light and O2 are absent (8–10). These cells show only negligible signs of pigment degradation and start photosynthesizing immediately after being reexposed to light (10, 27, 28). The metabolism that enables diatoms to survive in this low-energy environment was previously not known. Our study results reveal a correlation between the ability of diatoms to survive dark/anoxic conditions and the capacity to store NO3− intracellularly. This finding suggests that NO3−-storing diatom species possess a nonphotosynthetic, anaerobic metabolism that involves NO3− as an electron acceptor. In fact, dissimilatory NO3− reduction to NH4+ (i.e., DNRA) was found in A. coffeaeformis, the diatom species with the highest intracellular NO3− concentration in the present study.

Most of the intracellular NO3− pool in A. coffeaeformis (84–87%) was consumed within 1 d after the experimental shift to dark/anoxic conditions. This could indicate that dissimilatory NO3− reduction is largely used for the energy-demanding transition of the diatoms from the growing to the resting stage, whereas the ability to store NO3− intracellularly is linked to long-term survival. Synthesis of enzymes and structural proteins that are essential for the transition to the resting stage requires energy and nitrogen equivalents that might both be provided by NO3− reduction. Once the resting stage has been reached, the energy demand of the cells should be much lower. In fact, the consumption rate of intracellular NO3− decreased by a factor of ∼300 only a few hours after the onset of dark/anoxic conditions in the stable-isotope labeling experiment (Table 2). A. coffeaeformis cultures grew in none of the experiments under dark/anoxic conditions. This observation suggests that intracellular NO3− is used during the transition to a resting stage in sediments or to sustain cell metabolism during temporary stays in dark/anoxic water layers.

DNRA, Not Denitrification, Mediates Dissimilatory NO3− Reduction.

Three lines of evidence indicate that in A. coffeaeformis, dissimilatory NO3− reduction under dark/anoxic conditions proceeds as DNRA rather than denitrification: (i) The consumption of intracellular 15NO3− resulted in the concomitant and equimolar release of 15NH4+* (i.e., 15N-labeled NH4+ and organic N compounds) into the growth medium; (ii) the consumption of intracellular 15NO3− resulted in the release of only trace amounts of 15N-labeled N2O and N2 into the growth medium; and (iii) in the presence of light and O2, consumption of intracellular NO3− did not result in the release of NH4+ into the growth medium.

The cellular release of NH4+ under dark/anoxic conditions merits particular attention because the growth medium did not initially contain any NH4+. Under such NH4+-limited conditions, NH4+ normally remains inside the cell for N assimilation (29, 30). This was indeed the case under light/oxic conditions when the A. coffeaeformis cultures were growing, but not under dark/anoxic conditions when the cultures were not growing. In addition, the total amount of 15NH4+* released balanced the total amount of intracellular 15NO3− consumed (see the next paragraph). We conclude that in A. coffeaeformis, NO3− reduction under dark/anoxic conditions is dissimilatory, probably using the added acetate as the electron donor. However, only half of the 15NH4+* released was actually NH4+, indicating that the other half of the 15NO3− was reduced to organic N compounds that also were released by the cell. These N compounds should not be considered assimilation products, given that they are excreted by the cell completely. More likely, they represent unidentified byproducts of DNRA (possibly methyl amines or urea) that are also measured by the hypobromite assay (31). The cell-specific DNRA rates of A. coffeaeformis measured at 0–2.5 h and 8–192 h after the shift to dark/anoxic conditions correspond to 0.246 and 0.012 nmol 15NH4+* per mg of protein per min, respectively (cellular protein content data from ref. 32). For comparison, the DNRA rate of sulfide-oxidizing Thioploca spp. is 1 nmol 15NH4+* per mg of protein per min (21).

The time courses of total intracellular 15NO3− and extracellular 15NH4+* were not perfectly correlated (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the consumption rate of total intracellular 15NO3− was initially higher and later lower than the release rate of 15NH4+* (Table 2). By the end of incubation, however, the total amount of intracellular 15NO3− consumed balanced the total amount of 15NH4+* produced. This observation suggests the transient accumulation of an unidentified intermediate product that was further reduced to NH4+, which was then released to the medium (33).

DNRA in Eukaryotic Organisms.

A. coffeaeformis, a eukaryotic phototroph, is capable of dissimilatory NO3− reduction via the DNRA pathway. So far, DNRA activity has been identified only in prokaryotes (reviewed in ref. 33) and in fungi (23, 24). Intriguingly, some fungi use their assimilatory NO3− and NO2− reductases for generating ATP by dissimilatory NO3− and NO2− reduction (24, 34). Such a dual use of enzymes could be also realized in diatoms. In addition, analysis of the first two diatom genomes (35, 36) revealed that these eukaryotic organisms have incorporated prokaryotic genes by horizontal gene transfer from various marine bacteria (37). Thus, diatom species may possess combinations of metabolisms that were never previously found together in one organism (38). In the case of A. coffeaeformis, these are obviously photosynthesis and dissimilatory NO3− reduction.

Significance of DNRA in the Life Cycle of Diatoms.

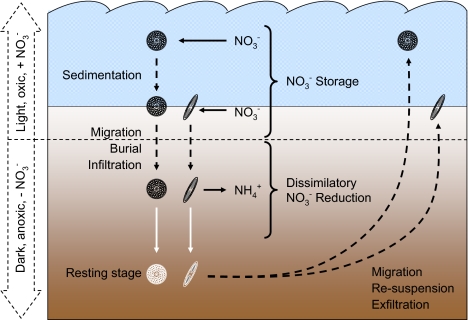

Dissimilatory NO3− reduction may have important functions in the life cycle of diatoms by providing a physiological means to (i) prepare the resting stage of a cell or (ii) bridge the temporary absence of light, O2, or nutrients. Under nutrient-replete conditions, diatoms take up NO3− for N assimilation, but they also may store NO3− and use it as an electron acceptor under dark/anoxic conditions (Fig. 4). In sediments, diatoms can be exposed to darkness and anoxia for short or long periods due to their own vertical migration (11), the activities of bioturbating animals (12), and the advective water flow through permeable sediments (39) (Fig. 4). DNRA activity may explain why the cellular metabolism of many diatoms remains relatively high in the absence of light and nutrients (28), and also why the recovery of diatoms from adverse conditions is immediate (27, 28). Thus, DNRA activity by buried diatoms may play a thus-far overlooked role in the functioning of sediments as seed banks for future diatom blooms (9).

Fig. 4.

Conceptual model of intracellular storage and dissimilatory reduction of NO3− by benthic and pelagic diatoms. Black arrows indicate cellular uptake or release of N compounds, black dashed arrows indicate transport of cells, and white arrows indicate physiological transition to resting stage. Block arrows on the left side and horizontal dashed line through the sediment delineate zones in which light, O2, and extracellular NO3− are present or absent. Diatom cells are stylized, with centric and pennate cells representing pelagic and benthic diatoms, respectively.

DNRA probably does not sustain the metabolism during long-term survival of diatoms under dark/anoxic conditions. Survival times of diatoms range from months to decades (summarized in refs. 8 and 9) and thus greatly exceed the turnover time of the intracellular NO3− pool determined in the present study. Even if this time span would be elongated by renewal of the NO3− pool through uptake from the sediment porewater (which has not yet been investigated), it seems unlikely that DNRA activity by diatoms could persist in deep sediment layers for decades.

Implications for Nitrogen Cycling.

Diatoms represent a massive and often overlooked cellular pool of NO3− in benthic aquatic ecosystems. Intertidal microphytobenthos harbors up to 10 times more NO3− than the sediment porewater (15), and the sedimentation of phytoplankton blooms further increases the cellular NO3− pool in sediments (7). The present study suggests that diatoms use this NO3− for DNRA under dark/anoxic conditions in the sediment (Fig. 4). The direct effect of DNRA by diatoms on the sedimentary nitrogen inventory may seem small, because NH4+ is rarely limiting in aquatic sediments. Nevertheless, DNRA by diatoms will retain fixed nitrogen in the sediment and thereby stimulate nitrification and indirectly denitrification and anammox as nitrogen removal pathways. If some of the diatoms die (e.g., due to mechanical disruption) before they have used up their intracellular NO3−, then other sediment microorganisms may use the NO3− directly for denitrification and anammox.

The NO3− storage capacity and dark survival potential of pelagic diatoms suggests that they are capable of DNRA as well. Assuming this, oceanic oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) are potentially important sites of DNRA activity by diatoms. Senescing diatom blooms sink out of the surface layer and pass deeper layers that are O2-poor, but NO3−-rich (6). Thus, sinking diatoms could exhibit DNRA activity in the dark/anoxic part of the water column at the expense of intracellular or extracellular NO3−. The prevalent nitrogen loss pathway in most OMZs is anammox, which requires NH4+ (40), which recently has been shown to be supplied by DNRA activity (41). Given their high abundance in the oceans (1), pelagic diatoms thus could be major transporters of NO3− and producers of NH4+ in the OMZs that are responsible for 30–50% of the nitrogen loss from the ocean (42, 43).

Materials and Methods

Strains and Cultivation.

Axenic strains of the marine diatoms D. brightwellii, Skeletonema costatum, Thalassiosira weissflogii, C. closterium, N. punctata, and A. coffeaeformis were obtained from the Provasoli–Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton. The diatoms were cultured in F/2 medium plus silicate (44) prepared with filtered (0.45 μm) and autoclaved North Sea seawater (salinity 35). The cultivation temperature was 15 °C, the light:dark cycle was 10:14 h, and the light intensity was 160 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The diatom strains maintained under these optimal growth conditions were frequently checked for possible contamination with bacteria by careful phase-contrast microscopy. All culture materials used in the experiments were also checked by DAPI staining of cell suspensions immobilized on polycarbonate membrane filters (0.2 μm; Osmonics). These checks were negative for all diatom strains except C. closterium. In the A. coffeaeformis experiments (see below), the possible contamination of culture materials by bacteria was also checked by PCR using bacteria domain-specific 16S rRNA gene primers (45); the results were negative.

Intracellular NO3− Accumulation.

The maximum intracellular NO3− concentration reached during the growth phase was determined for each strain by cultivation under optimal growth conditions. The cultures were repeatedly subsampled, after which the cells were washed three times with filtered and autoclaved NaCl solution (salinity 35), and then directly injected into the reaction chamber connected upstream to an NOx analyzer (CLD 86; EcoPhysics). At 90 °C, the acidified VCl3 (0.1 M) in the reaction chamber reduces both NO3− and NO2− that are liberated from the bursting cells to NO, which is measured by a chemiluminescence detector (46). For simplicity, the results of the NOx analyses are reported as NO3− concentrations throughout. The intracellular NO3− concentration was calculated from the total amount of NO3− in the injected subsample divided by the total cell volume of the respective diatom strain (see below). The NO3− concentration in the growth medium was determined after separation of cells and medium by gentle centrifugation (2 min at 100 × g) to avoid bursting of cells.

Determination of cell density in the subsamples was needed to monitor growth of the cultures and to calculate the intracellular NO3− concentration. This was done using a Fuchs–Rosenthal counting chamber and phase-contrast microscopy at 400× magnification. The strain-specific cell volume was determined by taking light micrographs of randomly chosen cells at 1,000× magnification (n > 100). Cell width and length were measured using UTHSCSA ImageTool (University of Texas Health Science Center). The strain-specific cell volume was estimated from these dimensions assuming a cylindrical cell shape.

Survival Under Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

Cultures of the five axenic diatom strains and the contaminated C. closterium strain (∼50 × 103 cells mL−1 for D. brightwellii and ∼500 × 103 cells mL−1 for all other strains) were transferred into sterile, completely dark Hungate bottles (50 mL) with a gas-tight septum in the lid. Through this lid, the headspace was flushed with N2 for 10 min to remove O2. Every few weeks, a subsample of each culture was obtained with a sterile syringe and transferred into a new culture flask containing fresh growth medium. As a measure of survival under optimal growth conditions (illuminated and oxic), the cultures were checked for growth or no growth within 1–2 wk of transfer. The last sampling of cells was carried out after 13 wk (in single cases after 28 wk), after which the Hungate bottles were opened to measure the O2 concentration in the cultures with a microsensor (47). O2 was not detected in any culture.

Consumption of Intracellular NO3− in Response to Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

A. coffeaeformis cells were grown under light/oxic conditions in F/2 medium plus silicate to allow uptake and intracellular storage of NO3−. After 2 d, the cells were harvested and washed three times with filtered and autoclaved NaCl solution (salinity 35; 10 min at 170 × g) to remove NO3− from the medium. After washing, the cells were transferred into artificial seawater (48) enriched with 200 μM Na-acetate, a commonly used electron donor for dissimilatory NO3− reduction (19) that promotes heterotrophic growth of many marine diatoms (49). Artificial seawater does not contain any NO3−, so the only source of NO3− in this experiment was NO3− stored intracellularly by the diatoms. Then 25 mL of the A. coffeaeformis cell suspension in artificial seawater was transferred into a sterile 50-mL Hungate bottle. The first subsample (0 h) was obtained before the Hungate bottle was sealed with a gas-tight septum and completely darkened with aluminum foil. The cell suspension was flushed with N2 for 15 min to remove O2. Subsamples were obtained with a sterile syringe at set time intervals over a 21-h period. For each subsample, 1 mL of well-mixed cell suspension was used to measure intracellular and extracellular NO3− concentrations as well as cell density (see above). To ensure that no O2 penetrated into the medium during sampling, the cell suspension was flushed again with N2 for several minutes after each sampling. All work was done under sterile conditions.

Dissimilatory NO3− Reduction in Response to Dark/Anoxic Conditions.

The pathway of dissimilatory NO3− reduction was studied with a stable isotope labeling experiment. Before the experiment, the intracellular NO3− pools of A. coffeaeformis cells were depleted by a starvation procedure. Axenic cells were washed three times with sterile NaCl solution (salinity 35; 10 min at 170 × g), transferred into artificial seawater (48), and exposed to dark and anoxic conditions for 2 d (see above). After this preincubation, no NO3− was detectable in the medium, and the intracellular NO3− concentration was <0.5 mM. A subsample of these cells was cultured under optimal growth conditions in F/2 medium plus silicate in artificial seawater enriched with 1 mM 15NO3− (98 atom%; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). After 5 d, a subsample of this culture was transferred into fresh F/2 medium plus silicate in artificial seawater, enriched with 1 mM 15NO3−, for 3 d. The cells were then harvested, washed three times with sterile NaCl solution (see above) to remove 15NO3− from the medium, and transferred into (15NO3−-free) artificial seawater enriched with 200 μM Na-acetate. Thus, the only NO3− source during this experiment was 15NO3− stored intracellularly by the diatoms.

The experiment was started by flushing the culture with He for 60 min to remove O2 and then transferring the anoxic culture into 33 culture tubes (12 mL; Labco) wrapped in aluminum foil. At set time intervals over a 192-h period, three culture tubes each were killed to obtain subsamples for measuring cell density, intracellular and extracellular NO3− concentrations, and concentrations of NH4+, 15NH4+, 15N-N2O, and 15N-N2 in the growth medium. Cell density and intracellular and extracellular NO3− concentrations were determined as described above. Subsamples (2.5 mL) for NH4+ and 15NH4+ analysis were centrifuged (10 min at 170 × g), and the cell-free supernatant was frozen at −20 °C for later analysis. NH4+ was measured photometrically according to the method of Kempers and Kok (50), and 15NH4+ was measured using the hypobromite assay of Warembourg (51), followed by N2 analysis by gas chromatography–isotope ratio mass spectrometry (VG Optima; Isotech). The hypobromite assay actually measures the sum of 15NH4+ and 15N-labeled volatile N compounds such as methyl amines (31), which we denote by 15NH4+*. Subsamples (9.5 mL) for 15N-N2O and 15N-N2 analysis were killed by adding 100 μL of saturated HgCl2 solution. 15N-N2O and 15N-N2 were measured by gas chromatography–isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Increases in 15N-N2O concentration with time indicate incomplete denitrification activity, whereas increases in 15N-N2 indicate complete denitrification activity.

As a negative control, an axenic culture of A. coffeaeformis pregrown in F/2 medium plus silicate enriched with 1 mM 14NO3− was washed three times with sterile NaCl solution to remove NO3− from the medium (see above) and then transferred into NO3−-free artificial seawater enriched with 200 μM Na-acetate. The culture (200 mL) was incubated under light/oxic conditions. At set time intervals over a 192-h period, subsamples were obtained to measure intracellular and extracellular NO3− concentrations as well as the concentration of NH4+ in the growth medium (see above). Cell density was determined throughout the experimental incubation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technicians of the Microsensor Group of MPI Bremen and K. Kohls for practical assistance; L. P. Nielsen and M. M. M. Kuypers for fruitful discussions, and two anonymous reviewers for comments that helped improve the manuscript. Financial support was provided by the Max Planck Society.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Nelson DM, Treguer P, Brzezinski MA, Leynaert A, Queguiner B. Production and dissolution of biogenic silica in the ocean: Revised global estimates, comparison with regional data and relationship to biogenic sedimentation. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1995;9:359–372. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lomas MW, Glibert PM. Comparisons of nitrate uptake, storage, and reduction in marine diatoms and flagellates. J Phycol. 2000;36:903–913. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Needoba JA, Harrison PJ. Influence of low light and a light:dark cycle on NO3- uptake, intracellular NO3-, and nitrogen isotope fractionation by marine phytoplankton. J Phycol. 2004;40:505–516. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Høgslund S. Nitrate storage as an adaptation to benthic life. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University; 2008. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smetacek VS. Role of sinking in diatom life-history cycles: Ecological, evolutionary and geological significance. Mar Biol. 1985;84:239–251. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bienfang PK, Harrison PJ, Quarmby LM. Sinking rate response to depletion of nitrate, phosphate and silicate in four marine diatoms. Mar Biol. 1982;67:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomstein E, Jensen MH, Sørensen J. Intracellular NH4+ and NO3- pools associated with deposited phytoplankton in a marine sediment (Aarhus Bight, Denmark) Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1990;61:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis J, Harris ASD, Jones KJ, Edmonds RL. Long-term survival of marine planktonic diatoms and dinoflagellates in stored sediment samples. J Plankton Res. 1999;21:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQuoid MR, Godhe A, Nordberg K. Viability of phytoplankton resting stages in the sediments of a coastal Swedish fjord. Eur J Phycol. 2002;37:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jewson DH, Lowry SF, Bowen R. Co-existence and survival of diatoms on sand grains. Eur J Phycol. 2006;41:131–146. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consalvey M, Paterson DM, Underwood GJC. The ups and downs of life in a benthic biofilm: Migration of benthic diatoms. Diatom Res. 2004;19:181–202. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamp A, Witte U. Processing of 13C-labelled phytoplankton in a fine-grained sandy-shelf sediment (North Sea): Relative importance of different macrofauna species. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2005;297:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sayama M. Presence of nitrate-accumulating sulfur bacteria and their influence on nitrogen cycling in a shallow coastal marine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:3481–3487. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3481-3487.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Høgslund S, Nielsen JL, Nielsen LP. Distribution, ecology and molecular identification of Thioploca from Danish brackish water sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;73:110–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Robledo E, Corzo A, Papaspyrou S, Jimenez-Arias JL, Villahermosa D. Freeze-lysable inorganic nutrients in intertidal sediments: Dependence on microphytobenthos abundance. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;403:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay BJ, Span ASW, Harman JMP. Nitrate respiration in primitive eukaryotes. Nature. 1983;303:333–336. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoun H, Tanimoto T. Denitrification by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum and involvement of cytochrome P-450 in the respiratory nitrite reduction. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11078–11082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Usuda K, Toritsuka N, Matsuo Y, Kim DH, Shoun H. Denitrification by the fungus Cylindrocarpon tonkinense: Anaerobic cell growth and two isozyme forms of cytochrome P-450nor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:883–889. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.883-889.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Risgaard-Petersen N, et al. Evidence for complete denitrification in a benthic foraminifer. Nature. 2006;443:93–96. doi: 10.1038/nature05070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piña-Ochoa E, et al. Widespread occurrence of nitrate storage and denitrification among Foraminifera and Gromiida. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1148–1153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908440107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otte S, et al. Nitrogen, carbon, and sulfur metabolism in natural thioploca samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3148–3157. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.3148-3157.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preisler A, et al. Biological and chemical sulfide oxidation in a Beggiatoa inhabited marine sediment. ISME J. 2007;1:341–353. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou ZM, et al. Ammonia fermentation, a novel anoxic metabolism of nitrate by fungi. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1892–1896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takasaki K, et al. Fungal ammonia fermentation, a novel metabolic mechanism that couples the dissimilatory and assimilatory pathways of both nitrate and ethanol: Role of acetyl CoA synthetase in anaerobic ATP synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12414–12420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Megonigal JP, Hines ME, Visscher PT. Anaerobic metabolism: Linkages to trace gases and aerobic processes. In: Schlesinger WH, editor. Biogeochemistry. Oxford, UK: Elsevier-Pergamon; 2004. pp. 317–424. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonin P. Anaerobic nitrate reduction to ammonium in two strains isolated from coastal marine sediment: A dissimilatory pathway. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;19:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters E, Thomas DN. Prolonged nitrate exhaustion and diatom mortality: A comparison of polar and temperate Thalassiosira species. J Plankton Res. 1996;18:953–968. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy AM, Cowles TJ. Effects of darkness on multi-excitation in vivo fluorescence and survival in a marine diatom. Limnol Oceanogr. 1997;42:1444–1453. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole JA, Brown CM. Nitrite reduction to ammonia by fermentative bacteria: Short-circuit in the biological nitrogen cycle. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;7:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vargas A, Strohl WR. Utilization of nitrate by Beggiatoa alba. Arch Microbiol. 1985;142:279–284. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Risgaard-Petersen N, Rysgaard S, Revsbech NP. Combined microdiffusion–hypobromite oxidation method for determining 15N isotope in ammonium. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1995;59:1077–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 32.De la Pena MR. Cell growth and nutritive value of the tropical benthic diatom, Amphora sp., at varying levels of nutrients and light intensity, and different culture locations. J Appl Phycol. 2007;19:647–655. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohan SB, Cole JA. The dissimilatory reduction of nitrate to ammonia by anaerobic bacteria. In: Bothe H, Ferguson S, Newton WE, editors. Biology of the Nitrogen Cycle. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Science; 2007. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watsuji TO, Takaya N, Nakamura A, Shoun H. Denitrification of nitrate by the fungus Cylindrocarpon tonkinense. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:1115–1120. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armbrust EV, et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: Ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science. 2004;306:79–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1101156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowler C, et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature. 2008;456:239–244. doi: 10.1038/nature07410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowler C, Vardi A, Allen AE. Oceanographic and biogeochemical insights from diatom genomes. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2010;2:333–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen AE, Vardi A, Bowler C. An ecological and evolutionary context for integrated nitrogen metabolism and related signaling pathways in marine diatoms. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrenhauss S, Witte U, Buhring SL, Huettel M. Effect of advective pore water transport on distribution and degradation of diatoms in permeable North Sea sediments. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;271:99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuypers MMM, et al. Massive nitrogen loss from the Benguela upwelling system through anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6478–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502088102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam P, et al. Revising the nitrogen cycle in the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4752–4757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812444106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruber N, Sarmiento JL. Global patterns of marine nitrogen fixation and denitrification. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1997;11:235–266. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Codispoti LA, et al. The oceanic fixed nitrogen and nitrous oxide budgets: Moving targets as we enter the anthropocene? Sci Mar. 2001;65:85–105. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guillard RR, Ryther JH. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms, I: Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can J Microbiol. 1962;8:229–239. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muyzer G, Hottenträger S, Teske A, Waver C. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA: A new molecular approach to analyse the genetic diversity of mixed microbial communities. In: Akkermanns AD, et al., editors. Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1995. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braman RS, Hendrix SA. Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium (III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal Chem. 1989;61:2715–2718. doi: 10.1021/ac00199a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Revsbech NP. An oxygen microsensor with a guard cathode. Limnol Oceanogr. 1989;34:474–478. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kester DR, Duedall IW, Connors DN, Pytkowicz RM. Preparation of artificial seawater. Limnol Oceanogr. 1967;12:176–178. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X, et al. Effects of organic carbon sources on growth, photosynthesis, and respiration of Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Appl Phycol. 2009;21:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kempers AJ, Kok CJ. Re-examination of the determination of ammonium as the indophenol blue complex using salicylate. Anal Chim Acta. 1989;221:147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warembourg FR. Nitrogen fixation in soil and plant systems. In: Knowles R, Blackburn TH, editors. Nitrogen Isotope Techniques. New York: Academic; 1993. pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]