Abstract

Recent treatments with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens have been shown to improve general clinical status in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; however, the prevalence of cognitive alterations and neurodegeneration has remained the same or has increased. These deficits are more pronounced in the subset of HIV patients with the inflammatory condition known as HIV encephalitis (HIVE). Activation of signaling pathways such as GSK3β and CDK5 has been implicated in the mechanisms of HIV neurotoxicity; however, the downstream mediators of these effects are unclear. The present study investigated the involvement of CDK5 and tau phosphorylation in the mechanisms of neurodegeneration in HIVE. In the frontal cortex of patients with HIVE, increased levels of CDK5 and p35 expression were associated with abnormal tau phosphorylation. Similarly, transgenic mice engineered to express the HIV protein gp120 exhibited increased brain levels of CDK5 and p35, alterations in tau phosphorylation, and dendritic degeneration. In contrast, genetic knockdown of CDK5 or treatment with the CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine improved behavioral performance in the water maze test and reduced neurodegeneration, abnormal tau phosphorylation, and astrogliosis in gp120 transgenic mice. These findings indicate that abnormal CDK5 activation contributes to the neurodegenerative process in HIVE via abnormal tau phosphorylation; thus, reducing CDK5 might ameliorate the cognitive impairments associated with HIVE.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enters the central nervous system (CNS) early in the progression of the disease, resulting in a spectrum of behavioral and motor alterations that range from mild cognitive deficits to dementia.1–4 Despite the notable efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in lowering HIV levels in plasma, recent studies have shown that HIV can persist in the CNS for a long period of time.5,6 Chronic presence of HIV in the brain is associated with neurodegenerative changes that contribute to cognitive alterations.4,7–10 Neuronal damage resulting from the neuroinflammatory process associated with HIV has been shown to lead to cognitive impairment.11–14 Increased life span of HIV patients and an increase in resistant strains of HIV has drawn attention to the prevalence of cognitive alterations in this population,8,15 and these deficits represent an important morbidity factor in HIV.3,6,16–18

HIV encephalitis (HIVE) is an inflammatory condition characterized by the presence of HIV-infected macrophages and microglial cells, astrogliosis, white matter damage, and neurodegeneration characterized by dendritic and synaptic damage in the neocortex and hippocampus.11 Viral proteins and cytokines produced by macrophages and microglia have been shown to induce neuronal dysfunction, neuron damage, and loss of nerve cells.19–28 HIV infection in the CNS has also been shown to promote neuronal calcium dysregulation, mitochondrial damage, oxidative stress,29,30 and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis.31 In addition, activation of calcium-dependent signaling pathways might also contribute to neurodegeneration. Among these, activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 (MAPK10; also known as c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3, or JNK3), double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR),32 glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β),7,33–35 and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5)7,36 have been shown to play a role.

Recent studies have shown that the abnormal activation of CDK5 might play a role in Alzheimer's disease (AD),37,38 Parkinson's disease39 and Huntington's disease.40 Under physiological conditions, CDK5 is activated by the neuron-specific proteins p35/p39; under pathological conditions, elevated intracellular calcium activates calpain-1, which in turns abnormally cleaves p35 into p25.38 The p25 fragment is more stable than p35 and constitutively activates CDK5,38 resulting in aberrant phosphorylation of neuronal substrates41 and in neuronal cell death. In patients with AD, the constitutively active p25/CDK5 complex results in the hyperphosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau, which is abundantly present in the neurofibrillary tangles and may contribute to neuronal cell death.37,38,41

Recent studies suggest that CDK5 might also play a role in the mechanisms of neurotoxicity in patients with HIV-associated cognitive alterations. For example, in a gene array study, we found that expression levels of CDK5 and related family members are dysregulated in the frontal cortex of patients with HIVE.42 Moreover, a recent study showed that in the brains of patients with HIV, calpain activity and the subsequent calpain-mediated generation of p25 from p35 were increased, leading to activation of the CDK5 pathway; however, the downstream targets involved in mediating the neurotoxic effects of HIV via abnormal CDK5 activation remain unclear.36 Thus, given the role of tau in CDK5-mediated neurotoxicity in AD, this protein is an important candidate to consider in the pathogenesis of HIVE.37,38

The primary objective of our study was to investigate in vivo the involvement of abnormal CDK5 activation and tau phosphorylation in the mechanisms of neurodegeneration in human cases of HIVE and in gp120 transgenic (Tg) mice. We found that abnormal activation of CDK5 resulted in aberrant tau phosphorylation, which in turn might contribute to dendritic damage and neurodegeneration. In contrast, partial genetic ablation of CDK5, or pharmacological manipulation with the CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine, reversed the tau pathology and neurodegenerative phenotype in the gp120 Tg mice.

Material and Methods

Subjects and Neuropathological Assessment

For the present study, HIV-positive cases with and without encephalitis were selected from a cohort of 43 HIV-positive cases from the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center and the California NeuroAIDS Tissue Network at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Subjects were excluded if they had a history of CNS opportunistic infections or non-HIV-related developmental, neurological, psychiatric, or metabolic conditions that might affect CNS functioning (eg, loss of consciousness exceeding 30 minutes, psychosis, substance dependence). For inclusion in the present study, a total of 16 age-matched cases were identified with and without encephalitis (n = 8 per group), and without other complications (Table 1). All cases had neuromedical and neuropsychological examinations within a median of 12 months before death. Most patients died as a result of acute bronchopneumonia or septicemia, and autopsy was performed within 24 hours of death. Autopsy findings were consistent with AIDS, and the associated pathology was most frequently due to systemic CMV, Kaposi sarcoma, and liver disease. In all cases, neuropathological assessment was performed in paraffin sections from the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices, and the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and brainstem stained with H&E, or immunolabeled with antibodies against p24 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, a marker of astrogliosis).43,44 The diagnosis of HIVE was based on the presence of microglial nodules, astrogliosis, HIV-p24 positive cells, and myelin pallor. Additional analysis was performed with a subset of five age-matched (non-HIV) cases from the UCSD-Medical Center Autopsy Service.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinico-Pathological Characteristics of HIV+ Cases with and without HIV Encephalitis

| Neuropathology diagnosis | Age | Sex | PM time | Brain weight | Cause of death | Neurocognitive diagnosis | CD4 counts | Plasma HIV RNA load | CSF HIV RNA load | History of stimulant dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 52 | F | 3 | 1300 | Diffuse alveolar damage | Normal | 315 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| Normal | 53 | M | 14 | 1410 | Bronchopneumonia | NPI | 420 | 4100 | 19 | No |

| Normal | 47 | M | 12 | 1200 | Bronchopneumonia | Normal | 48 | 404896 | 181 | Yes |

| Normal | 45 | M | 5 | 1220 | Bronchopneumonia | NPI | 785 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| Normal | 43 | M | 14 | 1210 | Septicemia | Normal | 320 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Normal | 46 | M | 18 | 1450 | Bronchopneumonia | MCMD | 6 | 1661323 | 688 | No |

| Normal | 56 | M | 6 | 1350 | Bronchopneumonia | Normal | 176 | 0 | 56 | No |

| Normal | 45 | M | 14 | 1410 | Congestive heart failure | Normal | 510 | 0 | 0 | No |

| HIV encephalitis | 31 | M | 8 | 1220 | Septicemia | HAD | 2 | 195352 | 15677 | Yes |

| HIV encephalitis | 39 | M | 12 | 1370 | Septicemia | NPI | 8 | 685115 | 2567 | No |

| HIV encephalitis | 40 | M | 10 | 1200 | Bronchopneumonia | HAD | 14 | 1615047 | 272277 | No |

| HIV encephalitis | 46 | M | 6 | 1125 | Septicemia | MCMD | 178 | 15001 | 116413 | No |

| HIV encephalitis | 43 | M | 6 | 1350 | Septicemia | HAD | 3 | 259000 | 47100 | No |

| HIV encephalitis | 37 | M | 12 | 1300 | Bronchopneumonia | HAD | 0 | 279747 | 9644 | Yes |

| HIV encephalitis | 27 | M | 8 | 1190 | Septicemia | NPI | 5 | 270951 | 592 | Yes |

| HIV encephalitis | 40 | F | 12 | 1040 | Bronchopneumonia | MCMD | 883 | 6962 | 29 | Yes |

PM, post-mortem; F, female; M, male; NPI, neuropsychological impairment; MCMD, minor cognitive/motor disorder; HAD, HIV-associated dementia.

Generation of GFAP-gp120 Tg Mice and Crosses with CDK5-Deficient Mice

For studies of CDK5 activation in an animal model of HIV-protein mediated neurotoxicity, Tg mice expressing high levels of gp120 under the control of the GFAP promoter were used.45 These mice develop neurodegeneration accompanied by astrogliosis, microgliosis,45 and memory deficits evinced in the water maze test.46 To study the effects of genetic CDK5 inhibition in vivo, CDK5 heterozygous deficient mice (Cdk5+/−) were crossed47 with the GFAP-gp120 Tg mice. Full ablation of both copies of CDK5 (Cdk5−/−)causes severe neurodevelopmental alterations, so to study CDK5 knockdown in the adult mouse brain, the Cdk5+/− animals were used as a model of reduced CDK5 activity. Cdk5+/− mice were kindly provided by the laboratory of Dr. Joseph Gleeson (UCSD). For in vivo studies, 12-month-old wild-type non-Tg, Cdk5+/−, gp120 Tg, or gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− crossed mice (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old) were tested in the water maze to assess learning and memory. The mice were sacrificed within one week of behavioral testing, and brains were removed for biochemical analyses of frozen or fixed brain tissues.

Roscovitine Infusion into GFAP-gp120 Tg Mice

For pharmacological treatments, an additional 24 mice (12-month-old non-Tg and gp120 Tg animals) received intracerebral infusions of vehicle (saline) alone or roscovitine (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at a concentration of 20 mg/kg into the lateral ventricle. Six mice per group received each treatment, as follows: n = 6 non-Tg with saline, n = 6 non-Tg with roscovitine, n = 6 gp120 Tg with saline, n = 6 gp120 Tg with roscovitine. For this purpose, mice were anesthetized, and under sterile conditions a 26-gauge stainless steel cannula was implanted stereotaxically into the lateral ventricle using the bregma as a reference (Franklin and Paxinos coordinates: bregma 0.5 mm; 1.1 mm lateral; depth 3 mm) and secured to the cranium using superglue. The cannula was connected via a 5-mm coil of V3 Biolab vinyl to a model 1007D osmotic minipump (Alzet, Cupertino, CA) surgically placed subcutaneously beneath the shoulder. The solutions were delivered at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/hour for 2 weeks. The pump was left for an additional 2 weeks and mice were tested in the water maze at 1 month after initiation of the infusions. All procedures were completed under the specifications set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (UCSD).

Water Maze Testing

In brief, as previously described,48 to evaluate learning and memory in the roscovitine-infused mice and in the gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice, the animals were trained in the water maze, beginning with a 3-day exposure to the visible platform (days 1 to 3). Then mice were tested for learning and memory with the hidden platform for 4 days (days 4 to 7), followed by one probe test and one final visible test trial on day 8. In the memory portion of the water maze behavioral test (probe test), the platform was removed to evaluate the time spent and distance traveled swimming in the target quadrant where the platform had been located. All experiments were approved by the UCSD Animal Subjects committee and were performed according to NIH recommendations for animal use.

Tissue Processing

In accordance with NIH guidelines for the humane treatment of animals, mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and were sacrificed by transcardial flush-perfusion with 0.9% saline. Brains were removed and divided sagittally. One hemibrain was postfixed in phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 48 hours and then was sectioned at 40 μm with a microtome (Vibratome 2000; Leica Microinstruments, Bannockburn, IL); the other hemibrain was snap-frozen and stored at −70°C for protein analysis. All experiments described were approved by the UCSD Animal Subjects committee and were performed according to NIH recommendations for animal use.

Immunoblot Analysis

Frontal cortex tissues from human and mouse brains were homogenized and fractionated using a buffer that facilitates separation of the membrane and cytosolic fractions (1.0 mmol/L HEPES, 5.0 mmol/L benzamidine, 2.0 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 3.0 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mmol/L magnesium sulfate, 0.05% sodium azide; final pH 8.8).49 In brief, as previously described,50,51 tissues from human and mouse brain samples (0.1 g) were homogenized in 0.7 mL of fractionation buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Samples were precleared by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature. Supernatants were retained and placed into appropriate ultracentrifuge tubes and were centrifuged at 436,000 × g for 1 hour at 4°C in a TL-100 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). This supernatant was collected, as representing the cytosolic fraction, and the pellets were resuspended in 0.2 mL of buffer and rehomogenized for the membrane fraction.

After determination of the protein content of all samples by a Pierce BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL), membrane and cytosolic fractions were loaded (20 μg total protein/lane), separated on 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gels, and electrophoresed in 5% morpholine propane sulfonic acid (MOPS) running buffer, and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membrane (Immobilon-P, 0.45 μm; Millipore, Billerica, MA) using NuPAGE transfer buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The membranes were blocked in either 5% nonfat milk/1% bovine serum albumin in PBS + 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) or in 5% bovine serum albumin in PBST for 1 hour. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CDK5 (C-8, 1:500), phosphorylated CDK5 (Tyr15, 1:500), p35/p25 (C-19, 1:500), CDK1/2 (AN21.2, 1:1000), or cyclin-D (H-295, 1:1000), all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were also probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies against CDK2 (M2, 1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pTau (Ser202, clone AT8, 1:1000; Pierce, Milwaukee, WI), total tau (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or a rabbit monoclonal antibody against total tau (1:1000; Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Blots were also probed with antibodies against pTau PHF-1 (Ser396/Ser404, 1:1000), CP13 (Ser202, 1:1000), CP9 (Thr231, 1:1000), and MC1 (conformation-specific tau antibody, 1:1000), generously provided by Dr. Peter Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine). After these primary antibodies, blots were stripped and probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against actin (C4, 1:1000; Millipore, Temecula, CA) as a loading control. Following incubation with primary antibodies, all blots were washed in PBS, incubated with secondary species-specific antibodies (1:5000 in bovine serum albumin-PBST; American Qualex, San Clemente, CA) and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ECL; Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). Images were obtained with the VersaDoc gel imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and semiquantitative analysis was performed using Quantity One software (version 4.5.1, Bio-Rad).

Immunocytochemical Analysis and Image Analysis

In brief, as previously described,51 microtome sections from the mid-frontal cortex (40 μm thick) of the HIV patients or from non-Tg, gp120 Tg, or Cdk5+/− mice were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CDK5 (1:1000, C-8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or p35/p25 (1:1000, C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CDK2 (1:250, M2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or cyclin-D (1:250, H-295, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or mouse monoclonal antibodies against pTau (Ser202, 1:1000, clone AT8, Pierce), CDK1/2 (1:250, AN21.2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or PHF1 (1:1000, generously provided by Dr. Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine), or a rabbit monoclonal antibody against total tau (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich). Primary antibody incubation was followed by incubation with secondary biotinylated IgG, then avidin-horseradish peroxidase and diaminobenzidine detection. All sections were processed under the same standardized conditions. Immunostained sections were imaged with an Olympus digital microscope, and assessment of levels of CDKs, p35, and tau immunoreactivity was performed using the Image-Pro Plus software package (version 4.5.1, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). For each case, a total of three sections (10 digital images per section, at ×400 magnification) were analyzed to estimate the average number of immunolabeled cells per unit area (mm2) and the average intensity of the immunostaining (corrected optical density).

Analysis of Neurodegeneration

The integrity of the neuronal structure was evaluated as previously described.52,53 In brief, blind-coded, 40-μm-thick microtome sections from mouse brains fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were immunolabeled with mouse monoclonal antibodies against microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2, a dendritic marker; 1:200; Millipore). After overnight incubation, sections were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:75; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), transferred to SuperFrost slides (Fisher Scientific, Tustin, CA), and mounted under glass coverslips with antifading medium (Vector Laboratories). All sections were processed under the same standardized conditions. The immunolabeled blind-coded sections were serially imaged with a laser scanning confocal microscope (MRC-1024; Bio-Rad) and analyzed with ImageJ v1.43 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD), as previously described.45,54 For each mouse, a total of three sections were analyzed; for each section, four fields in the frontal cortex and hippocampus were examined. Results were expressed as percent area of the neuropil occupied by immunoreactive signal. An additional set of sections were immunostained with the mouse monoclonal glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, an astroglial marker; 1:500; Millipore), followed by secondary biotinylated IgG, avidin-horseradish peroxidase, and diaminobenzidine detection. All sections were processed under the same standardized conditions. Immunostained sections were imaged with a digital Olympus microscope and the Image-Pro Plus program (version 4.5.1, Media Cybernetics).

Culture and Treatment of Primary Human Neuronal Cells

Primary human neurons (HNs) from normal fetal cerebral cortex were from ScienCell Research Laboratories (San Diego, CA). The primary human cells were obtained in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The HN cultures were characterized by the supplier using immunofluorescent methods with antibodies against neurofilament, MAP2, and β-III-tubulin. The majority of the cells (>95%) are terminally differentiated neurons. The HNs were negative for HIV-1, HBV, HCV, mycoplasma, bacteria, yeast, and fungi. The HNs were obtained from ScienCell Research Laboratories as cryopreserved secondary cultures and were used directly for experiments without further subculturing. Cells were plated onto polylysine/laminin-coated 96-well plates, glass coverslips, or cell culture plates in neuronal medium (NM; ScienCell Research Laboratories), which is a serum-free medium containing neuronal growth supplements. Cells were cultured for 24 hours to allow adherence to the coverslips or plates, followed by treatment with roscovitine (5 to 60 μmol/L) or gp120 (100 ng/mL) alone or in combination for up to 72 hours. Aliquots of the cell growth medium were taken at various time points and were analyzed for release of lactate dehydrogenase (a marker of cell toxicity) using the CytoTox96 assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For detection of apoptosis, the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) detection method with the ApopTag in situ apoptosis detection kit (Millipore) was used, with some modifications, as described previously.55–57 For assessment of dendrite development and integrity, cells on coverslips were immunolabeled with an antibody against MAP2 (as described above for microtome sections, under Analysis of Neurodegeneration). Coverslips were mounted under glass with antifading medium (Vector Laboratories) for confocal microscopy analysis.

Double Immunolabeling and Confocal Microscopy Imaging

Double-labeled immunocytochemical analysis was performed using the Tyramide Signal Amplification-Direct (Red) system (NEN Life Sciences, Boston, MA) to detect CDK5. Specificity of this system was tested by deleting each primary antibody. For this purpose, sections were double-labeled with the rabbit antibodies against CDK5 (1:20,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) detected with Tyramide Red, and pTau (AT8 and PHF-1) detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:75, Vector Laboratories), and sections were mounted under glass coverslips with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). All sections were processed simultaneously under the same conditions and experiments were performed twice for reproducibility. Sections were imaged with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Radiance 2000; Bio-Rad) system equipped with a Nikon Eclipse E600FN microscope and using a Nikon Plan Apo 60× oil objective (NA 1.4; oil immersion).

Statistical Analysis

All of the analyses were conducted on blind-coded samples. After the results were obtained, the code was broken and data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 4.0c, La Jolla, CA). Comparisons among groups were performed with unpaired Student's t-test and χ2 analysis, or by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's or Tukey-Kramer tests for comparisons among more than two groups. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Results

Alterations in CDK5 Expression Are Associated with Abnormal Tau Phosphorylation in Patients with HIVE

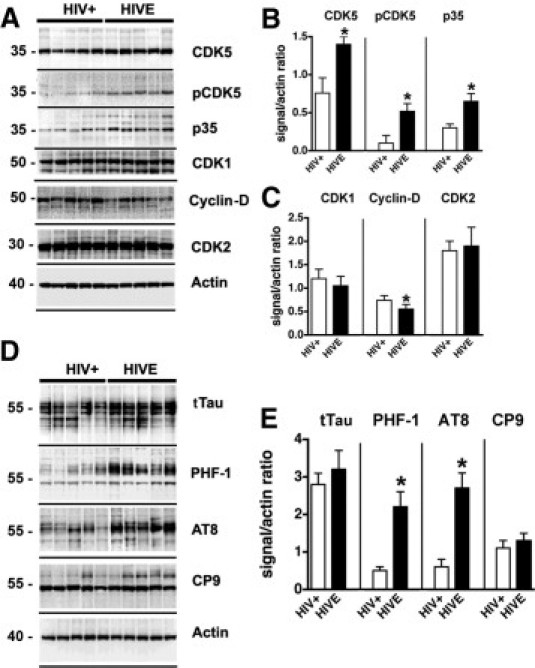

To characterize the alterations in the CDK5 signaling pathway in HIV patients with and without encephalitis, immunoblot analysis was performed. Both CDK5 and pCDK5 were identified as 35-kDa bands. Compared with HIV-positive control cases with no alterations in the brain, in cases with HIVE there was a 75% increase in the levels of total CDK5, and activated pCDK5 was increased approximately threefold in the frontal cortex (Figure 1, A and B). Similarly, levels of p35 were increased approximately twofold in HIVE cases (Figure 1, A and B). The cases analyzed with HIVE ranged from mild to severe, based on the number of microglial nodules and HIV p24 load (Table 1). There was a tendency for cases with more severe microgliosis to have higher levels of CDK5; however, this difference was not statistically significant (probably because of the great variability in HIV p24 levels in the HIVE cases). Other members of this kinase family, such as CDK1 (Figure 1, A and C) and CDK2 (Figure 1, A and C) did not differ between the two HIV groups analyzed. In cases with HIVE, however, cyclin-D was reduced by 20% (Figure 1, A and C).

Figure 1.

Immunoblot analysis of levels of CDKs and phosphorylated tau (pTau) expression in HIV encephalopathy (HIVE) cases. Western blot analysis was performed with frontal cortex homogenates from HIV-positive cases without encephalitis and from cases with HIVE. For each lane, 15 μg of the membrane fraction was used. A: Representative blot probed with antibodies against CDK5, pCDK5, p35/p25, CDK1, cyclin-D, and CDK2. B and C: Analysis of the immunoreactivity levels of CDKs and activators, expressed as ratios relative to actin levels (to correct for loading). D: Representative blot probed with antibodies against total tau (tTau), pTau Ser396 and Ser404 (PHF-1), pTau Ser202 (AT8), and pTau Thr231 (CP9). E: Analysis of the levels of tau immunoreactivity, expressed as ratios relative to actin levels (to correct for loading). *P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (n = 8 cases per group).

Previous studies in AD have shown that aberrant activation of CDK5 can result in abnormal phosphorylation of substrates such as tau38; however, the consequences of abnormal CDK5 activation in patients with HIV are unknown. Immunoblot analysis with antibodies against total tau (tTau) identified this microtubule binding protein as four bands between 50 kDa and 60 kDa (Figure 1D). The levels of tTau were comparable between HIV-positive cases with no brain alterations and those with HIVE (Figure 1, D and E). In contrast, the levels of phosphorylated tau (pTau), as detected by the PHF-1 and AT8 antibodies (which recognize phosphorylation at Ser386/Ser404 and Ser202 epitopes, respectively) were significantly increased in the frontal cortex of cases with HIVE (Figure 1, D and E). Other phospho-epitopes detected by the CP9 antibody (Thr231) (Figure 1, D and E) were not different between the control HIV-positive and HIVE groups.

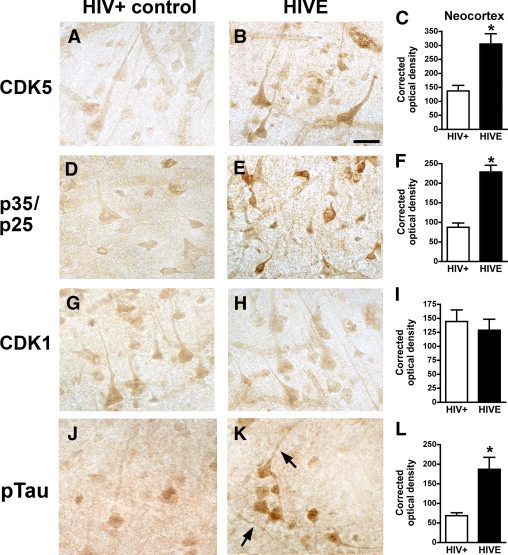

Similar to the Western blot results, immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against CDK5 (Figure 2, A–C) and p35/p25 (Figure 2, D–F) showed a significant increase in the levels of immunoreactivity in HIVE cases, compared with HIV-positive controls without encephalitis. In contrast, levels of CDK1 were similar between the groups (Figure 2, G–I). Moreover, levels of pTau detected with the PHF-1 antibody were significantly elevated in the cases with HIVE (Figure 2, J–L). In the HIV-positive control cases, only a mild immunoreactive signal (Figure 2J) was detected in the neuronal cell bodies. In contrast, in cases with HIVE, there was abundant pTau immunostaining in the cell bodies and axons of pyramidal neurons in the frontal cortex (Figure 2K). In the HIVE cases, there was also pTau immunoreactivity in the apical dendrites of some neurons and in the axons in the white matter tracts (Figure 2K).

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical analysis of CDKs and pTau immunoreactivity in HIVE cases. Representative bright-field images are shown from immunolabeled 40-μm-thick microtome sections from the frontal cortex. A and B: CDK5 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in layer III in HIV-positive (A) and HIVE (B) cases. C: Image analysis shows increased corrected optical density values of CDK5 immunoreactivity in HIVE cases, compared with HIV-positive controls. D and E: p35/p25 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in layer III in HIV-positive (D) and HIVE (E) cases. F: Image analysis shows increased corrected optical density values of p35/p25 immunoreactivity in HIVE cases, compared with HIV-positive controls. G and H: CDK1 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in layer III in HIV-positive (G) and HIVE (H) cases. I: Image analysis shows similar CDK1 levels in HIVE and HIV-positive controls. J: PHF-1 immunoreactivity in a control HIV-positive case. K: pTau (PHF-1 antibody) in pyramidal neurons and axons (arrows) in an HIVE case. L: Image analysis shows increased corrected optical density values of pTau (PHF-1) immunoreactivity in HIVE cases, compared with HIV-positive controls. *P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (n = 8 cases per group). Scale bar = 15 μm (all images).

Gp120 Tg Mice Display Alterations in CDK5 Expression and Abnormal Tau Phosphorylation

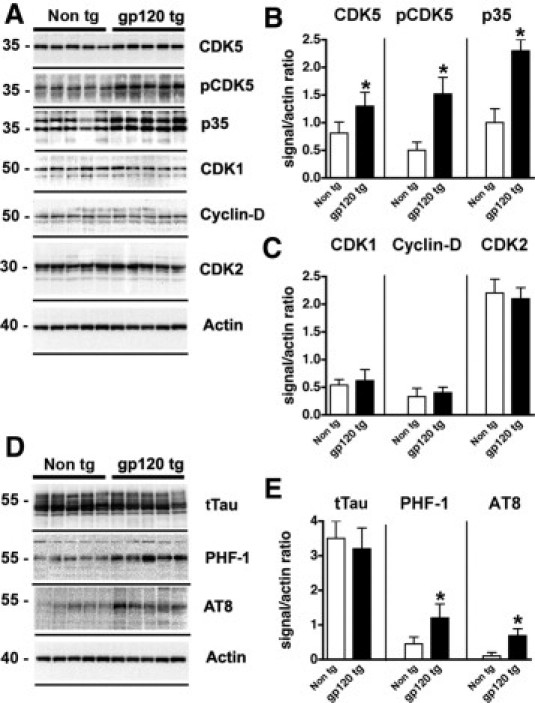

To investigate whether alterations in CDK5 activation and tau phosphorylation were also present in experimental models of HIV neurotoxicity, immunoblot analysis was performed in membrane fractions from brain homogenates of the GFAP-gp120 Tg mouse model.45 Compared with age-matched non-Tg littermate controls, in gp120 Tg mice there was a 70% increase in the levels of total CDK5, accompanied by a threefold increase in the levels of activated pCDK5 in the neocortex (Figure 3, A and B). Compared with non-Tg controls, the levels of p35 were increased by approximately twofold in gp120 Tg mice (Figure 3, A and B). Other members of this kinase family, such as CDK1, cyclin-D, and CDK2 (Figure 3, A and C), did not differ between the non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice. Immunoblot analysis with antibodies against tTau identified this microtubule binding protein as four bands between 50 kDa and 60 kDa (Figure 3D). The levels of tTau were comparable between the non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice (Figure 3, D and E). In contrast, the levels of pTau, as detected by the PHF-1 and AT8 antibodies (which detect the phosphorylation at Ser386/Ser404 and Ser202, respectively), were significantly increased in the gp120 Tg mice (Figure 3, D and E).

Figure 3.

Immunoblot analysis of levels of CDKs and pTau expression in gp120 Tg mice. Western blot analysis was performed with total homogenates from the cortex of non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice. For each lane, 15 μg of the membrane fraction was used. A: Representative blot probed with antibodies against CDK5, pCDK5, p35/p25, CDK1, cyclin-D, and CDK2. B and C: Analysis of the immunoreactivity levels of CDKs and activators, expressed as ratios relative to actin levels o correct for loading. D: Representative blot probed with antibodies against tTau, pTau Ser396 and Ser404 (PHF-1), and pTau Ser202 (AT8). E: Analysis of the levels of tau immunoreactivity, expressed as ratios relative to actin levels (to correct for loading). *P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old).

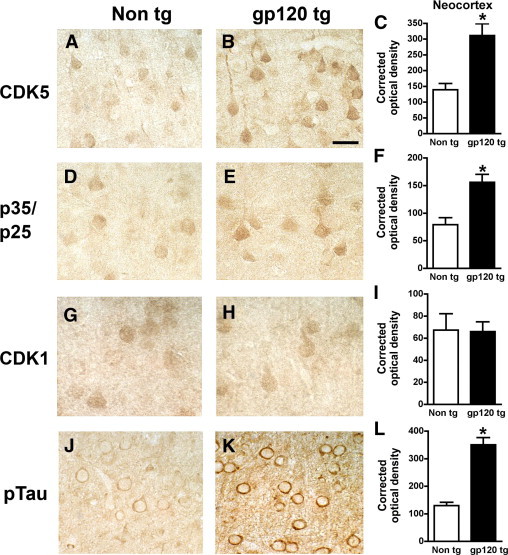

Similar to the immunoblot studies, immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against CDK5 (Figure 4, A–C) and p35/p25 (Figure 4, D–F) showed a significant increase in the levels of immunoreactivity in the gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls. In contrast, levels of CDK1 were similar between the two groups of mice (Figure 4, G–I). The levels of pTau immunolabeling using the PHF-1 antibody were significantly elevated in the gp120 Tg mice (Figure 4, J–L). In the Tg mice, abundant pTau immunoreactivity was detected in the cytoplasm of pyramidal neurons in the frontal cortex (Figure 4K) and hippocampus. In the gp120 Tg model, the majority of the gliosis and neuronal alterations are observed in the neocortex, hippocampus, and white matter, with some mild gliosis also present in the basal ganglia and brainstem.45 Notably, the alterations in CDK5 and pTau levels were more prominent in the regions with the highest gp120 levels (ie, the frontal cortex and hippocampus).

Figure 4.

Immunocytochemical analysis of CDKs and pTau immunoreactivity in gp120 Tg mice. All micrographs show representative bright-field images from the frontal cortex. A and B: CDK5 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in layer III in non-Tg (A) and gp120 Tg (B) mice. C: Image analysis shows increased CDK5 immunoreactivity, expressed as corrected optical density, in gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls. D and E: p35/p25 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in non-Tg (D) and gp120 Tg (E) mice. F: Image analysis shows increased p35/p25 immunoreactivity, expressed as corrected optical density, in gp120 Tg, compared with non-Tg control mice. G and H: CDK1 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in non-Tg (G) and gp120 Tg (H) mice. I: Image analysis shows similar CDK1 levels in non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice. J: PHF-1 immunoreactivity in non-Tg control mice. K: pTau (PHF-1 antibody) immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons of gp120 Tg mice. L: Image analysis shows increased pTau (PHF-1) immunoreactivity, expressed as corrected optical density, in gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls. *P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old). Scale bar = 15 μm (all images).

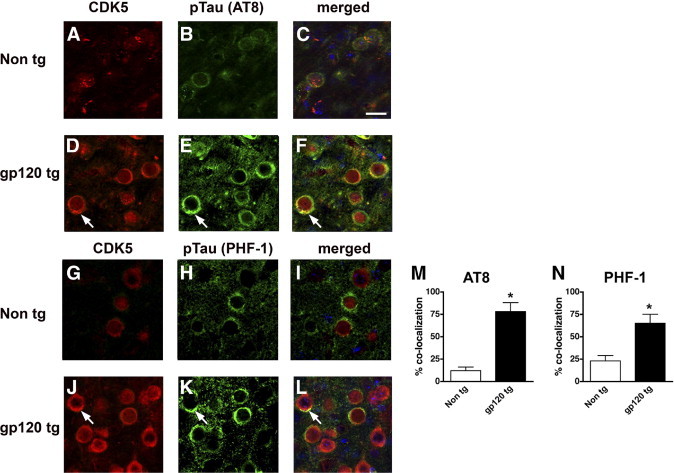

CDK5 Is Colocalized with Neurons Displaying Tau Phosphorylation in gp120 Tg Mice

To determine whether neurons displaying high levels of CDK5 immunoreactivity colocalized with pTau, double-immunolabeling studies were performed. Laser scanning confocal microscopy of the double-labeled sections showed that, in the non-Tg control mice, levels of CDK5 and pTau immunoreactivity with the AT8 or PHF-1 antibodies were mild (Figure 5, A, B, G, and H), and both markers colocalized in only approximately 10% to 20% of the neurons analyzed (Figure 5, C, I, M, and N). In contrast, in the gp120 Tg mice, CDK5 and pTau (AT8 or PHF-1) immunoreactivity were increased (Figure 5, D, E J, and K), and both markers colocalized in approximately 60% to 70% of the neurons analyzed (Figure 5, F, L, M, and N).

Figure 5.

Double-labeled immunocytochemical analysis of CDK5 and pTau colocalization in gp120 Tg mice. Laser scanning confocal micrographs are from the frontal cortex of non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice (12 months old) double-labeled with antibodies against CDK5 (red) and pTau (green). Cell nuclei (blue) were costained with DAPI. A–C: Low levels of CDK5 and pTau (AT8) immunoreactivity in non-Tg mice. D–F: High levels of CDK5 expression and colocalization (arrows) with pTau (AT8) in gp120 Tg mice. G–I: Low levels of CDK5 and pTau (PHF-1) immunoreactivity in non-Tg mice. J–L: High levels of CDK5 expression and colocalization (arrows) with pTau (PHF-1) in gp120 Tg mice. M and N: Semiquantitative analysis of the percentage of cortical neurons displaying colocalization of CDK5 and pTau immunoreactivity with the AT8 (M) or PHF-1 (N) antibodies in cortical neurons from non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice. *P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old). Scale bar = 10 μm (all images).

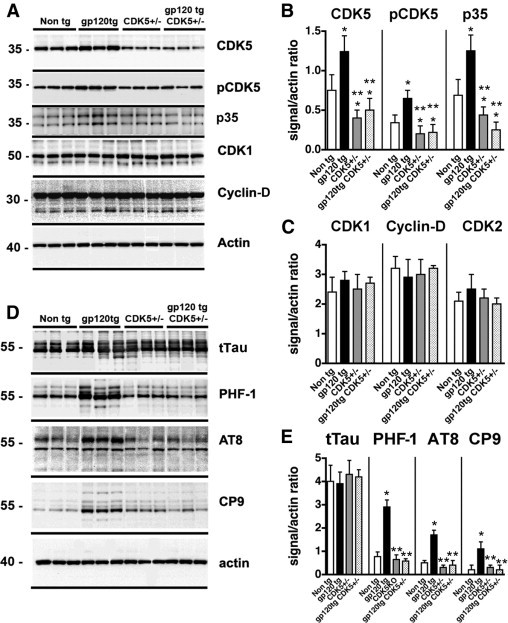

Cdk5 Knockdown Reduces the Accumulation of Phosphorylated Tau in gp120 Tg Mice

To verify that the increased expression and activation of CDK5 contributes to the abnormal phosphorylation of tau, gp120 Tg mice were cross-bred with CDK5 knockdown mice. Only CDK5 heterozygous mice (Cdk5+/−) were used for the study, because the homozygous-deficient genotype results in severe CNS developmental abnormalities.47 According to immunoblot analysis using membrane fractions, levels of CDK5, pCDK5, and p35 were increased in the gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls (Figure 6, A and B), but were reduced by approximately 60% in the Cdk5+/− and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice (Figure 6, A and B). However, levels of CDK1, cyclin-D, and CDK2 were comparable among the four groups of mice (Figure 6, A and C). Levels of tTau were similar among the non-Tg, gp120, and Cdk5+/− mice and the crosses (Figure 6, D and E). Compared with non-Tg mice, levels of pTau immunoreactivity with the PHF-1, AT8, and CP9 antibodies were elevated in gp120 Tg mice (Figure 6, D and E). In contrast, in the gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− group, levels of pTau were similar to those in controls (Figure 6, D and E).

Figure 6.

Immunoblot analysis of CDKs and pTau levels in crosses between gp120 Tg and Cdk5+/− mice. Western blot analysis was performed with homogenates from the cortex of animals generated from the crosses. For each lane, 15 μg of the membrane fraction was used. A: Representative blot probed with antibodies against CDK5, pCDK5, p35/p25, CDK1, and cyclin-D. B and C: Analysis of the immunoreactivity levels of CDKs and activators, expressed as ratios relative to actin levels (to correct for loading). D: Representative blot probed with antibodies against tTau, pTau Ser396 and Ser404 (PHF-1), pTau Ser202 (AT8), and pTau Thr231 (CP9). E: Analysis of the levels of tau immunoreactivity, expressed as ratios relative to actin levels (to correct for loading). *P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test, compared with control non-Tg mice (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old). **P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, compared with gp120 Tg mice.

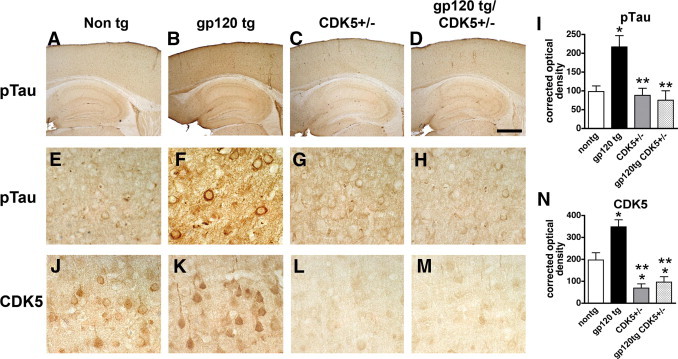

Consistent with the immunoblot studies, immunocytochemical analysis showed that, compared with non-Tg mice (Figure 7, A and E), in the gp120 Tg mice (Figure 7, B and F) there was a significant increase in the levels of pTau immunoreactivity in neurons and the neuropil throughout the neocortex and hippocampus (Figure 7I). In contrast, in the gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice (Figure 7, D, H, and I), the levels of pTau immunoreactivity were similar to those in controls (Figure 7, E–I). Similar patterns of increased CDK5 and p35/p25 immunoreactivity were detected at lower-power imaging in neurons and the neuropil throughout the cortex and hippocampus of gp120 Tg, mice, compared with non-Tg controls (data not shown). Higher-power images of immunocytochemical analysis with an antibody against CDK5 confirmed that, compared with non-Tg mice, immunoreactivity levels were increased in the gp120 Tg animals, whereas in the Cdk5+/− and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/−, levels were approximately 50% less than in the non-Tg controls (Figure 7, J–N).

Figure 7.

Effects of CDK5 knockdown on pTau immunoreactivity in gp120 Tg mice. Micrographs are representative bright-field images from brain sections of non-Tg, gp120 Tg, Cdk5+/−, and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. A–D: Low-magnification view of the neocortex and hippocampus in brain sections from non-Tg, gp120 Tg, Cdk5+/−, and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice immunostained with an antibody against pTau (PHF-1). E–H: Higher-magnification view shows pyramidal neurons in the neocortex of non-Tg, gp120 Tg, Cdk5+/−, and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− immunostained with an antibody against pTau (PHF-1). I: Image analysis shows increased levels of pTau (PHF-1) immunoreactivity in gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg and Cdk5+/− mice. J–M: Higher-magnification view of CDK5 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neurons in the neocortex of non-Tg, gp120 Tg, Cdk5+/−, and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. N: Image analysis shows reduced CDK5 levels, expressed as corrected optical density values, in Cdk5+/− and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice, compared with non-Tg controls. *P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test, compared with control non-Tg mice (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old). **P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, compared with gp120 Tg. Scale bar: 375 μm (A–D); 25 μm (E–H and J–M).

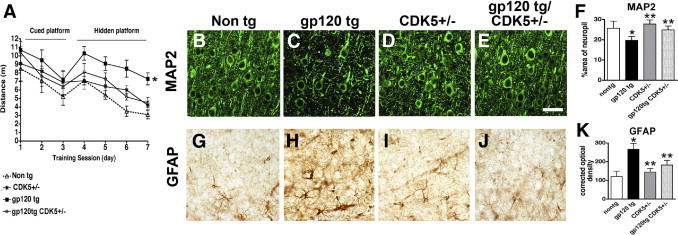

Genetic and Pharmacological Reduction of CDK5 Expression or Activation Ameliorates the Neurodegenerative Pathology in gp120 Tg Mice

Increased activation of CDK5 might be associated with neurodegeneration in HIVE and in gp120 Tg mice, and knocking down CDK5 in gp120 Tg mice was found to reduce levels of tau phosphorylation. In this context, it is possible that reducing CDK5 might decrease the neurodegenerative pathology in gp120 Tg mice. For this purpose, control mice and crosses between gp120 Tg and Cdk5+/− mice were tested in the water maze, and neurodegeneration was assessed by immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy (Figure 8). During the training segment (visible platform) of the water maze test, all mice performed at similar levels, indicating that no motor deficits were present (Figure 8A). In contrast, during the spatial learning period of the test (submerged platform), the gp120 Tg animals exhibited impaired performance, taking a longer path before locating the platform than did the non-Tg mice (Figure 8A). Compared with the gp120 Tg mice, the gp120 Tg mice in the Cdk5+/− background performed similarly to the non-Tg controls and to the Cdk5+/− mice (Figure 8A). Analysis of markers of neurodegeneration showed that, compared with non-Tg controls, in the gp120 Tg mice there was a decrease in MAP2-immunoreactive dendrites in the neocortex (Figure 8, B, C, and F) and an increase in GFAP levels (a marker of astrogliosis) (Figure 8, G, H, and K). In contrast, gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− displayed levels of MAP2 and GFAP immunoreactivity similar to non-Tg and Cdk5+/− controls (Figure 8, B–K).

Figure 8.

Effects of CDK5 knockdown on water maze performance and markers of neurodegeneration in gp120 Tg mice. A: Performance in the visible (days 1 to 3) and hidden (days 4 to 7) portions of the water maze test in crosses between gp120 Tg and Cdk5+/− mice. During the visible portion of the test, mice from all four groups performed with similar abilities; during the hidden part of the test (submerged platform), gp120 Tg mice took a longer path to complete the test, compared with non-Tg mice. The Cdk5+/− and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice performed similarly to the non-Tg controls. B–E: Laser scanning confocal micrographs show MAP2 immunolabeling of the neuropil in the neocortex of non-Tg, gp120 Tg, Cdk5+/−, and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. F: Image analysis shows decreased levels of MAP2 immunoreactivity in gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls, and recovery in the gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. G–J: Bright-field micrographs show astroglial cells immunolabeled with antibody against GFAP in the neocortex of non-Tg, gp120 Tg, Cdk5+/−, and gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. K: Image analysis shows increased GFAP immunoreactivity in gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg, and recovery in the gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. *P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test, compared with control non-Tg mice (n = 8 mice per group, 12 months old). **P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, compared with gp120 Tg. Scale bar = 25 μm (all images).

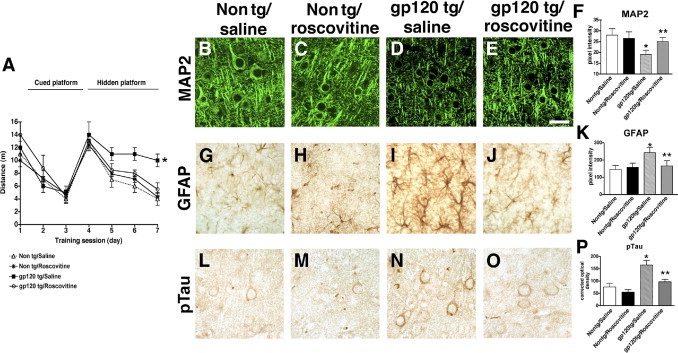

To further verify that down-modulating the abnormal activation of the CDK5 pathway rescues the neurodegenerative defects and tau pathology in the gp120 Tg mice, an alternative pharmacological approach was implemented. For this purpose, mice received intraventricular infusions either with the CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine or with saline as a vehicle control, followed by behavioral and immunocytochemical analyses (Figure 9). During the training segment of the test (visible platform), all mice performed at similar ability levels (Figure 9A). During the spatial learning period of the test (hidden platform), however, compared with the saline- or roscovitine-treated non-Tg mice, the saline-treated gp120 Tg animals exhibited impaired performance, taking a longer path to locate the platform (Figure 9A). In contrast to the saline-treated gp120 Tg mice, the roscovitine-treated gp120 Tg performed with similar ability as the saline-treated non-Tg group (Figure 9A). As expected, saline- or roscovitine-treated non-Tg controls displayed comparable levels of MAP2 and GFAP immunoreactivity, whereas saline-treated gp120 Tg mice showed reduced levels of MAP2-immunoreactive dendrites (Figure 9, B–D and F) in the neocortex and an increase in levels of astrogliosis (GFAP) (Figure 9, G–I and K). Notably, roscovitine-treated gp120 Tg mice displayed levels of MAP2 and GFAP immunoreactivity similar to saline-treated non-Tg controls (Figure 9, B–K).

Figure 9.

Effects of roscovitine infusion on water maze performance and markers of neurodegeneration in gp120 Tg mice. A: Performance in the visible (days 1 to 3) and hidden (days 4 to 7) portions of the water maze test in non-Tg or gp120 Tg mice treated with saline control or roscovitine. During the visible portion of the test, mice from all four groups performed with similar abilities; during the hidden part of the test (submerged platform), saline-treated gp120 Tg mice took a longer path to complete the test, compared with saline- or roscovitine-treated non-Tg controls. The roscovitine-treated gp120 Tg mice performed similarly to the non-Tg controls. B–E: Laser scanning confocal micrographs show MAP2 immunolabeling of the neuropil in the neocortex of saline- or roscovitine-treated non-Tg or gp120 Tg mice. F: Image analysis shows decreased MAP2-immunoreactive dendrites in saline-treated gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls, and recovery in the gp120 Tg mice treated with roscovitine. G–J: Bright-field micrographs show astroglial cells immunolabeled with antibody against GFAP in the neocortex of saline- or roscovitine-treated non-Tg or gp120 Tg mice. K: Image analysis shows increased GFAP immunoreactivity in saline-treated gp120 Tg mice, compared with non-Tg controls, and recovery in the gp120 Tg mice treated with roscovitine. L–O: Bright-field micrographs show pyramidal neurons in the neocortex of saline- or roscovitine-treated non-Tg or gp120 Tg mice immunostained with antibody against pTau (PHF-1). P: Image analysis shows reduced levels of pTau immunoreactivity in roscovitine-treated gp120 Tg mice, compared with saline-treated gp120 Tg mice. *P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test, compared with control non-Tg mice (n = 6 mice per group, 12 months old). **P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, compared with gp120 Tg. Scale bar = 25 μm.

To confirm whether the reversal of tau hyperphosphorylation observed in gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− animals could be recapitulated with pharmacological inhibition of CDK5, tau immunoreactivity was assessed in the brains of non-Tg and gp120 Tg mice treated with roscovitine (Figure 9, L–P). This analysis demonstrated that, similar to genetic knockdown of CDK5 levels, pharmacological inhibition with roscovitine significantly reduced the abnormal tau phosphorylation detected in the brains of gp120 Tg mice (Figure 9, O and P). Taken together, these studies suggest that modulating the CDK5 pathway—either by partial genetic ablation or using a pharmacological approach—rescues the behavioral and neurodegenerative deficits in gp120 Tg mice via a mechanism involving reduced tau hyperphosphorylation.

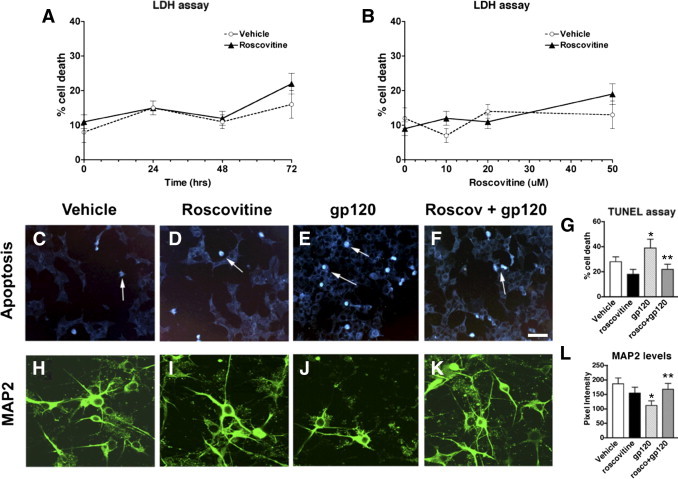

Roscovitine Is Protective Against gp120-Induced Toxicity in Primary Human Neuronal Cell Cultures

To further confirm that roscovitine is neuroprotective against gp120 in an independent system, we exposed primary human neurons to gp120 alone or with roscovitine pretreatment. First, to assess potential cytotoxicity of the drug treatment in the cultured cells, we analyzed the dose- and time-dependent effects of roscovitine (Figure 10, A and B). Using a cytotoxicity assay that measures lactate dehydrogenase release into the medium, these studies showed that, at a dose of 5 to 20 μmol/L for up to 48 hours, roscovitine was well tolerated and did not compromise neuronal survival above vehicle control (Figure 10, A and B). When primary human neuronal cultures were treated with gp120 (100 ng/mL) for 48 hours, significant cell damage, as illustrated by the apoptosis assay (TUNEL), and a reduction in MAP2-immunoreactive dendrites was observed, compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 10, C, E, G, H, J, and L). In contrast, pretreatment with roscovitine at 20 μmol/L for 24 hours was protective against gp120 toxicity (Figure 10, C–L). These results are consistent with the in vivo studies in Tg mice, and support the contention that roscovitine is neuroprotective against the toxic effects of gp120 in models of HIV-associated neurotoxicity.

Figure 10.

Time course and dose-response analysis of viability of primary human neuronal cells treated with roscovitine, gp120, or both roscovitine and gp120. A: Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) viability assay of time course experiment of cells exposed to 20 μmol/L roscovitine for 0 to 72 hours. B: LDH viability assay of dose response experiment with cells treated with 0 to 50 μmol/L roscovitine for 24 hours. C–G: Increased apoptosis (TUNEL assay) in cells treated with gp120 is rescued by roscovitine pretreatment. H–L: Decreased MAP2-immunoreactivity in cells treated with gp120 is rescued by roscovitine pretreatment. *P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's test, compared with vehicle-treated control cultures (n = 3). **P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, compared with gp120 treatment. Scale bar = 25 μm (all images). Arrows indicate apoptotic cell nuclei.

Discussion

The present study showed that, in the brains of patients with HIVE and in gp120 Tg mice, increased expression of CDK5 can lead to neurotoxicity via abnormal tau phosphorylation. This is consistent with recent studies showing that aberrant activation of the CDK57,36 and GSK3β7,33–35,58 signaling pathways contribute to the neurodegenerative pathology in patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. Although a previous study focused on the role of p35 and CDK5 activation via the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR),36 the present study investigated the contribution of abnormal activation of this pathway to tau hyperphosphorylation in patients with HIVE. In patients with AD, abnormal activation of CDK5 and GSK3β have been implicated in the aberrant phosphorylation of tau and associated substrates.37,38,59–62 The hyperphosphorylation of tau has been associated with neurodegeneration via apoptosis.63–65 Moreover, in some amyloid precursor protein (APP) Tg models of AD, deletion of tau is protective.66,67 The p25/CDK5 complex associates with the neurofibrillary tangles in patients with AD,68 and CDK5 has been shown to abnormally phosphorylate tau at Ser 199, 202, 396, and 404,69 sites that are recognized by the AT8 and PHF-1 antibodies.70

In the present study, the levels of immunoreactivity with both of these phosphorylation epitope-specific tau antibodies were elevated in patients with HIVE and in gp120 Tg mice. In the HIVE cases and in gp120 Tg mice, AT8 and PHF-1 immunoreactivities were associated with pyramidal neurons and irregular axons, and were colocalized with neurons displaying increased CDK5 levels. However, it is worth noting that the patterns of AT8 and PHF-1 immunolabeling in patients with HIVE were different from what has been observed in patients with AD. Although in advanced AD cases the pTau immunoreactivity is associated with dystrophic neurites, neuropil threads, and neurofibrillary tangles,71–75 in HIVE cases and in gp120 Tg mice there was diffuse nonfibrillar pTau immunostaining detected in neurons and throughout the neuropil. Increased CDK5 and p35/p25 immunoreactivities were also detected throughout the neuropil of HIVE brains and gp120 Tg mice, reflecting the expression of these proteins in various cellular compartments that extend into the dendritic arbor and synapses. The diffuse pattern of pTau immunolabeling was reminiscent of what has been described in patients with preclinical AD or in the pretangle stage,71,76 suggesting that in HIVE some of the initial triggering events are present, even though other features such as amyloid β accumulation in AD are evident only at later stages. Recent studies have shown that in older patients with HIVE, the levels of amyloid β are increased.77–80 This accumulation of amyloid β could trigger enhanced aberrant tau phosphorylation, and so the potential effects of aging on p25/CDK5 activation in patients with HIVE deserve further investigation.

Further supporting a role for CDK5 and tau in the neurodegenerative pathology of HIV infection, the present study showed that knockdown of CDK5 in gp120 Tg mice ameliorated the learning and memory deficits displayed in the water maze, decreased the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau, reduced astrogliosis, and rescued the dendritic neuronal alterations as revealed by using an antibody against MAP2. Because homozygous CDK5 ablation results in severe CNS developmental abnormalities,47,81 for the present study we used hemizygous knockout mice (Cdk5+/−) for crosses with the gp120 Tg mice. Of note, although tau hyperphosphorylation was reduced in gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice, compared with gp120 Tg animals, there was no significant reduction in Cdk5+/− mice compared with wild-type controls. This may be a consequence of the presence of a number of different kinases that are capable of phosphorylating tau, including GSK3β and CaMK-II (among others). Under physiological conditions, these other kinases may maintain levels of phosphorylated tau at normal and nontoxic levels. Furthermore, there is some crosstalk between the GSK3β and CDK5 signaling pathways,82 so it is possible that GSK3β may compensate to some extent for the partial loss of CDK5 activity. In contrast, abnormal activation induced by gp120 might be alleviated by the reduction of CDK5 expression, resulting in decreased levels of hyperphosphorylated tau in gp120 Tg/Cdk5+/− mice. In fact, because levels of CDK5 were elevated in HIVE cases and in gp120 Tg mice, it is possible that the knockdown might function by normalizing the activity of CDK5 down to baseline levels.

The mechanisms by which HIV might dysregulate CDK5 are not completely clear. HIV or HIV proteins could interfere with the transcriptional regulation of p35 and CDK5.42 Of note, in the present study we found increased immunoreactivity of CDK5 and p35, and a more substantial increase in levels of active pCDK5 in the brains of HIVE patients and gp120 Tg mice, compared with controls. This difference is most likely due to the requirement for interaction of CDK5 with p35/p25 for activation. Several groups have previously demonstrated that levels of p35/p25 are the rate-limiting step for CDK5 activation, and that CDK5 activity correlates more closely with p35/p25 levels than with total CDK5 levels.83,84 Thus, the twofold to threefold increase in p35 activator levels that we observed in HIVE brains and in gp120 Tg mice, in combination with a twofold increase in total CDK5 levels, may account for the more substantial threefold to fivefold increase detected in CDK5 autophosphorylation and activity.

Another possible mechanism regulating increased CDK5 activity in HIVE and mouse models might involve the ability of HIV proteins (eg, gp120) and excitotoxins23,25,85,86 released by HIV-infected microglia to trigger increased intracellular calcium influx.87,88 This, in turn, could activate calpain cleavage of p35 into p25 and result in abnormal activation of CDK5.36 This is consistent with the proposed neurotoxic mechanism of abnormal CDK5 activation in AD,37,38 and with studies in the brains of HIV patients and in primary neurons treated with conditioned media from HIV-infected macrophages showing NMDAR-dependent activation of p25/CDK5.36

In agreement with a role for aberrant CDK5 activation in neurodegeneration in HIV models, a previous in vitro study by Wang et al36 showed that treatment with the CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine protected primary neurons from the neurotoxic effects of HIV-infected monocyte-derived macrophages. This is consistent with the present in vitro studies demonstrating neuroprotection by roscovitine against gp120 toxicity in primary human neuronal cultures. Moreover, we also showed that intracerebral infusion of roscovitine with an osmotic minipump ameliorated the behavioral deficits and reduced the neurodegenerative and tau pathology in gp120 Tg mice. It should be noted that, in addition to its action as an inhibitor of CDK5, roscovitine is also active against a number of CDKs at inhibitory concentration IC50 values of <1 μmol/L, including CDK1, CDK2, CDK7, and CDK9.89,90 Although CDK5 is the predominant CDK expressed in the adult brain, and is likely the primary target of roscovitine delivered intracerebrally, this fact highlights the importance of developing more selective pharmacological inhibitors of CDK5.

In the present study, roscovitine was delivered intracerebrally because it has previously been predicted to have only a limited ability to enter the brain, with a logBB value of −0.81.91 However, recent studies have demonstrated transport of this inhibitor across the blood-brain barrier, and therapeutic efficacy in models of acute brain injury.92,93 Previous pharmacokinetic studies showed after a single intraperitoneal dose of roscovitine, in rat pups equivalent levels of the drug were detected in blood and brain compartments, and roscovitine induced a significant functional CDK5 inhibition in all brain regions studied at 2 hours.94 In contrast, in adult rats, levels of roscovitine in the brain were approximately 70% to 80% lower than levels in the blood.94,95 Notably, although levels of roscovitine were lower in the brain than in the blood of adult animals, no metabolites of the drug were detected in the brain, compared with a number of metabolites present in blood and other tissues.95 Thus, the observed therapeutic efficacy of peripherally-delivered roscovitine in models of neuronal injury may be related to a relative resistance of roscovitine to degradation in the brain compartment. Together, these studies suggest that roscovitine may have measurable neuroprotective effects in models of neurodegeneration when administered peripherally.

The neuroprotective effects of roscovitine observed in the present study are consistent with findings from previous studies showing that roscovitine infusion ameliorates neurodegenerative alterations in a model of Niemann-Pick disease,96 and in a model of traumatic brain injury.97 In these models, roscovitine also reduced abnormal phosphorylation of tau. Similarly, in gp120 Tg mice in the Cdk5 heterozygous deficient background, we showed a reversal of behavioral and neurodegenerative alterations, and significantly reduced accumulation of pTau.

In conclusion, the present study showed that aberrant activation of the CDK5 pathway might play a role in neurodegeneration in HIVE via accumulation of pTau. Furthermore, these results support the possibility that treatment with roscovitine or a derivative with improved brain penetration parameters and enhanced specificity could represent a promising possibility for developing new neuroprotective treatments for patients with HIV-associated cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory of Dr. Joseph Gleeson (University of California, San Diego) for providing the Cdk5+/− mouse line, and Dr. Peter Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) for providing the tau antibodies.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the NIH (MH062962, MH076681, MH79881, MH45294, MH59745, MH58164, DA026306, and DA12065) and by the California NeuroAIDS Tissue Network (U01 MH83506). The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) is supported by Center award MH62512 from the NIH-National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- 1.Gendelman H.E., Persidsky Y., Ghorpade A., Limoges J., Stins M., Fiala M., Morrisett R. The neuropathogenesis of the AIDS dementia complex. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl A):S35–S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McArthur J. Neurological manifestations of AIDS. Medicine. 1987;66:407–437. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198711000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McArthur J.C., Haughey N., Gartner S., Conant K., Pardo C., Nath A., Sacktor N. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia: an evolving disease. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:205–221. doi: 10.1080/13550280390194109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González-Scarano F., Martín-García J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell J.E. An update on the neuropathology of HIV in the HAART era. Histopathology. 2004;45:549–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray F., Chrétien F., Vallat-Decouvelaere A.V., Scaravilli F. The changing pattern of HIV neuropathology in the HAART era. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:429–440. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crews L., Patrick C., Achim C.L., Everall I.P., Masliah E. Molecular pathology of neuro-AIDS (CNS-HIV) Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:1045–1063. doi: 10.3390/ijms10031045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everall I.P., Hansen L.A., Masliah E. The shifting patterns of HIV encephalitis neuropathology. Neurotox Res. 2005;8:51–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03033819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence D.M., Major E.O. HIV-1 and the brain: connections between HIV-1-associated dementia, neuropathology and neuroimmunology. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diesing T.S., Swindells S., Gelbard H., Gendelman H.E. HIV-1-associated dementia: a basic science and clinical perspective. AIDS Read. 2002;12:358–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masliah E., Heaton R.K., Marcotte T.D., Ellis R.J., Wiley C.A., Mallory M., Achim C.L., McCutchan J.A., Nelson J.A., Atkinson J.H., Grant I. Dendritic injury is a pathological substrate for human immunodeficiency virus-related cognitive disorders: HNRC Group The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:963–972. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masliah E., Ge N., Achim C.L., DeTeresa R., Wiley C.A. Patterns of neurodegeneration in HIV encephalitis. J NeuroAIDS. 1996;1:161–173. doi: 10.1300/j128v01n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masliah E., Ge N., Mucke L. Pathogenesis of HIV-1 associated neurodegeneration. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:57–67. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiley C.A., Achim C.L. Human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis and dementia. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:559–560. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wendel K.A., McArthur J.C. Acute meningoencephalitis in chronic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: putative central nervous system escape of HIV replication. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1107–1111. doi: 10.1086/378300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacktor N., McDermott M.P., Marder K., Schifitto G., Selnes O.A., McArthur J.C., Stern Y., Albert S., Palumbo D., Kieburtz K., De Marcaida J.A., Cohen B., Epstein L. HIV-associated cognitive impairment before and after the advent of combination therapy. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:136–142. doi: 10.1080/13550280290049615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maschke M., Kastrup O., Esser S., Ross B., Hengge U., Hufnagel A. Incidence and prevalence of neurological disorders associated with HIV since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:376–380. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant I., Heaton R., Atkinson J., Group H. Neurocognitive disorder in HIV-1 infection. HIV and dementia: proceedings of the NIMH-sponsored conference “Pathogenesis of HIV infection of the brain: impact on function and behavior”. In: Oldstone M.B.A., Vitkovic L., editors. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 1995. pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nath A. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) proteins in neuropathogenesis of HIV dementia. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(Suppl 2):S193–S198. doi: 10.1086/344528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul M., Lipton S.A. Chemokines and activated macrophages in HIV gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8212–8216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meucci O., Fatatis A., Simen A.A., Bushell T.J., Gray P.W., Miller R.J. Chemokines regulate hippocampal neuronal signaling and gp120 neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14500–14505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders V.J., Pittman C.A., White M.G., Wang G., Wiley C.A., Achim C.L. Chemokines and receptors in HIV encephalitis. AIDS. 1998;12:1021–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giulian D., Vaca K., Noonan C. Secretion of neurotoxins by mononuclear phagocytes infected with HIV-1. Science. 1990;250:1593–1596. doi: 10.1126/science.2148832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulliam L., Zhou M., Stubblebine M., Bitler C.M. Differential modulation of cell death proteins in human brain cells by tumor necrosis factor alpha and platelet activating factor. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:530–538. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981115)54:4<530::AID-JNR10>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pulliam L., Clarke J.A., McGuire D., McGrath M.S. Investigation of HIV-infected macrophage neurotoxin production from patients with AIDS dementia. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(06)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z., Trillo-Pazos G., Kim S.Y., Canki M., Morgello S., Sharer L.R., Gelbard H.A., Su Z.Z., Kang D.C., Brooks A.I., Fisher P.B., Volsky D.J. Effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on astrocyte gene expression and function: potential role in neuropathogenesis. J Neurovirol. 2004;10(Suppl 1):25–32. doi: 10.1080/753312749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brandimarti R., Khan M.Z., Fatatis A., Meucci O. Regulation of cell cycle proteins by chemokine receptors: a novel pathway in human immunodeficiency virus neuropathogenesis? J Neurovirol. 2004;10(Suppl 1):108–112. doi: 10.1080/753312761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martín-García J., Kolson D.L., González-Scarano F. Chemokine receptors in the brain: their role in HIV infection and pathogenesis. AIDS. 2002;16:1709–1730. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozdener H. Molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 associated neurodegeneration. J Biosci. 2005;30:391–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02703676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipton S. HIV-related neuronal injury: Potential therapeutic intervention with calcium channel antagonists and NMDA antagonists. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:181–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02780669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garden G.A., Budd S.L., Tsai E., Hanson L., Kaul M., D'Emilia D.M., Friedlander R.M., Yuan J., Masliah E., Lipton S.A. Caspase cascades in human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4015–4024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-04015.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alirezaei M., Watry D.D., Flynn C.F., Kiosses W.B., Masliah E., Williams B.R., Kaul M., Lipton S.A., Fox H.S. Human immunodeficiency virus-1/surface glycoprotein 120 induces apoptosis through RNA-activated protein kinase signaling in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11047–11055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2733-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashimoto M., Sagara Y., Everall I.P., Mallory M., Everson A., Langford D., Masliah E. Fibroblast growth factor 1 regulates signaling via the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta pathway: Implications for neuroprotection. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32985–32991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maggirwar S.B., Tong N., Ramirez S., Gelbard H.A., Dewhurst S. HIV-1 Tat-mediated activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta contributes to Tat-mediated neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1999;73:578–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewhurst S., Maggirwar S.B., Schifitto G., Gendelman H.E., Gelbard H.A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3 beta) as a therapeutic target in neuroAIDS. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2:93–96. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., White M.G., Akay C., Chodroff R.A., Robinson J., Lindl K.A., Dichter M.A., Qian Y., Mao Z., Kolson D.L., Jordan-Sciutto K.L. Activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 by calpains contributes to human immunodeficiency virus-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2007;103:439–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumann K., Mandelkow E.M., Biernat J., Piwnica-Worms H., Mandelkow E. Abnormal Alzheimer-like phosphorylation of tau-protein by cyclin-dependent kinases cdk2 and cdk5. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:417–424. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80849-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee M.S., Kwon Y.T., Li M., Peng J., Friedlander R.M., Tsai L.H. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature. 2000;405:360–364. doi: 10.1038/35012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qu D., Rashidian J., Mount M.P., Aleyasin H., Parsanejad M., Lira A., Haque E., Zhang Y., Callaghan S., Daigle M., Rousseaux M.W., Slack R.S., Albert P.R., Vincent I., Woulfe J.M., Park D.S. Role of Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of Prx2 in MPTP toxicity and Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2007;55:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anne S.L., Saudou F., Humbert S. Phosphorylation of huntingtin by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 is induced by DNA damage and regulates wild-type and mutant huntingtin toxicity in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7318–7328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1831-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahlijanian M.K., Barrezueta N.X., Williams R.D., Jakowski A., Kowsz K.P., McCarthy S., Coskran T., Carlo A., Seymour P.A., Burkhardt J.E., Nelson R.B., McNeish J.D. Hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofilament and cytoskeletal disruptions in mice overexpressing human p25, an activator of cdk5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040577797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masliah E., Roberts E.S., Langford D., Everall I., Crews L., Adame A., Rockenstein E., Fox H.S. Patterns of gene dysregulation in the frontal cortex of patients with HIV encephalitis [Erratum appeared in J Neuroimmunol 2005, 162:197] J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Achim C.L., Heyes M.P., Wiley C.A. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus, immune activation factors, and quinolinic acid in AIDS brains. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2769–2775. doi: 10.1172/JCI116518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masliah E., Achim C., Ge N., DeTeresa R., Terry R., Wiley C. Spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neocortical damage. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:321–329. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toggas S.M., Masliah E., Rockenstein E.M., Rall G.F., Abraham C.R., Mucke L. Central nervous system damage produced by expression of the HIV-1 coat protein gp120 in transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;367:188–193. doi: 10.1038/367188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D'Hooge R., Franck F., Mucke L., De Deyn P.P. Age-related behavioural deficits in transgenic mice expressing the HIV-1 coat protein gp120. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4398–4402. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohshima T., Ward J.M., Huh C.G., Longenecker G., Veeranna, Pant H.C., Brady R.O., Martin L.J., Kulkarni A.B. Targeted disruption of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 gene results in abnormal corticogenesis, neuronal pathology and perinatal death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11173–11178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rockenstein E., Adame A., Mante M., Moessler H., Windisch M., Masliah E. The neuroprotective effects of Cerebrolysin in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease are associated with improved behavioral performance. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:1313–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pham E., Crews L., Ubhi K., Hansen L., Adame A., Cartier A., Salmon D., Galasko D., Michael S., Savas J.N., Yates J.R., Glabe C., Masliah E. Progressive accumulation of amyloid-beta oligomers in Alzheimer's disease and in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice is accompanied by selective alterations in synaptic scaffold proteins. FEBS J. 2010;277:3051–3067. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cole G., Dobkins K., Hansen L., Terry R., Saitoh T. Decreased levels of protein kinase C in Alzheimer brain [Erratum appeared in Brain Res 1991, 558:177] Brain Res. 1988;452:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masliah E., Rockenstein E., Veinbergs I., Mallory M., Hashimoto M., Takeda A., Sagara, Sisk A., Mucke L. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rockenstein E., Mante M., Alford M., Adame A., Crews L., Hashimoto M., Esposito L., Mucke L., Masliah E. High beta-secretase activity elicits neurodegeneration in transgenic mice despite reductions in amyloid-beta levels: implications for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32957–32967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rockenstein E., Adame A., Mante M., Larrea G., Crews L., Windisch M., Moessler H., Masliah E. Amelioration of the cerebrovascular amyloidosis in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with the neurotrophic compound cerebrolysin. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mucke L., Abraham C., Ruppe M., Rockenstein E., Toggas S., Alford M., Masliah E. Protection against HIV-1 gp120-induced brain damage by neuronal overexpression of human amyloid precursor protein (hAPP) J Exp Med. 1995;181:1551–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biebl M., Cooper C.M., Winkler J., Kuhn H.G. Analysis of neurogenesis and programmed cell death reveals a self-renewing capacity in the adult rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2000;291:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper-Kuhn C.M., Kuhn H.G. Is it all DNA repair?: Methodological considerations for detecting neurogenesis in the adult brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;134:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biebl M., Winner B., Winkler J. Caspase inhibition decreases cell death in regions of adult neurogenesis. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1147–1150. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200508010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schifitto G., Zhong J., Gill D., Peterson D.R., Gaugh M.D., Zhu T., Tivarus M., Cruttenden K., Maggirwar S.B., Gendelman H.E., Dewhurst S., Gelbard H.A. Lithium therapy for human immunodeficiency virus type 1-associated neurocognitive impairment. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:176–186. doi: 10.1080/13550280902758973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wen Y., Planel E., Herman M., Figueroa H.Y., Wang L., Liu L., Lau L.F., Yu W.H., Duff K.E. Interplay between cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta mediated by neuregulin signaling leads to differential effects on tau phosphorylation and amyloid precursor protein processing. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2624–2632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5245-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rockenstein E., Torrance M., Adame A., Mante M., Bar-on P., Rose J.B., Crews L., Masliah E. Neuroprotective effects of regulators of the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta signaling pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease are associated with reduced amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1981–1991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4321-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noble W., Planel E., Zehr C., Olm V., Meyerson J., Suleman F., Gaynor K., Wang L., LaFrancois J., Feinstein B., Burns M., Krishnamurthy P., Wen Y., Bhat R., Lewis J., Dickson D., Duff K. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by lithium correlates with reduced tauopathy and degeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6990–6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500466102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flaherty D.B., Soria J.P., Tomasiewicz H.G., Wood J.G. Phosphorylation of human tau protein by microtubule-associated kinases: gSK3beta and cdk5 are key participants. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:463–472. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001101)62:3<463::AID-JNR16>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mookherjee P., Johnson G.V. tau phosphorylation during apoptosis of human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2001;921:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mattson M.P. Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:120–129. doi: 10.1038/35040009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Augustinack J.C., Schneider A., Mandelkow E.M., Hyman B.T. Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:26–35. doi: 10.1007/s004010100423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roberson E.D., Scearce-Levie K., Palop J.J., Yan F., Cheng I.H., Wu T., Gerstein H., Yu G.Q., Mucke L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ittner L.M., Ke Y.D., Delerue F., Bi M., Gladbach A., van Eersel J., Wölfing H., Chieng B.C., Christie M.J., Napier I.A., Eckert A., Staufenbiel M., Hardeman E., Götz J. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Augustinack J.C., Sanders J.L., Tsai L.H., Hyman B.T. Colocalization and fluorescence resonance energy transfer between cdk5 and AT8 suggests a close association in pre-neurofibrillary tangles and neurofibrillary tangles. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:557–564. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gong C.X., Liu F., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K. Post-translational modifications of tau protein in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:813–838. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Plattner F., Angelo M., Giese K.P. The roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 in tau hyperphosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25457–25465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vincent I., Rosado M., Davies P. Mitotic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:413–425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmidt M.L., Lee V.M., Trojanowski J.Q. Relative abundance of tau and neurofilament epitopes in hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1069–1075. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mandelkow E.M., Mandelkow E. Tau in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:425–427. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]