Abstract

Bioincompatibility of peritoneal dialysis fluids (PDF) limits their use in renal replacement therapy. PDF exposure harms mesothelial cells but induces heat shock proteins (HSP), which are essential for repair and cytoprotection. We searched for cellular pathways that impair the heat shock response in mesothelial cells after PDF-exposure. In a dose-response experiment, increasing PDF-exposure times resulted in rapidly increasing mesothelial cell damage but decreasing HSP expression, confirming impaired heat shock response. Using proteomics and bioinformatics, simultaneously activated apoptosis-related and inflammation-related pathways were identified as candidate mechanisms. Testing the role of sterile inflammation, addition of necrotic cell material to mesothelial cells increased, whereas addition of the interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) antagonist anakinra to PDF decreased release of inflammatory cytokines. Addition of anakinra during PDF exposure resulted in cytoprotection and increased chaperone expression. Thus, activation of the IL-1R plays a pivotal role in impairment of the heat shock response of mesothelial cells to PDF. Danger signals from injured cells lead to an elevated level of cytokine release associated with sterile inflammation, which reduces expression of HSP and other cytoprotective chaperones and exacerbates PDF damage. Blocking the IL-1R pathway might be useful in limiting damage during peritoneal dialysis.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a frequently used renal replacement modality and an attractive alternative to hemodialysis. The main drawback of PD is the limited biocompatibility of commonly used PD fluids (PDF). Due to the high concentration of glucose and glucose degradation products resulting from heat sterilization, as well as acidic lactate buffer, PDF exposure causes damage to the mesothelial cells (MCs) that are lining the peritoneal cavity.1–3

Data available from in vitro and in vivo models of PD show that PDF exposure does not only result in cell death or damage. We have recently shown that cell damage by PDF or components thereof leads to a complex cellular stress response, where heat shock proteins (HSP) play an important role but other biological processes are also induced.4,5 HSP, a group of highly conserved proteins, are some of the best studied mediators of cellular repair. PDF exposure is able to induce HSP expression depending on the composition of the fluid6 and induced HSP confer cytoprotection to the stressed MCs.7,8

It has long been suspected that smoldering inflammation leads to a worse therapy outcome.9 Because both the signaling pathways involved in the regulation of the inflammatory response and the regulatory elements of the heat shock response share common elements, intracellular cross talk between these pathways will very likely play a role as soon as both pathways are triggered. This cross talk indeed can be observed in other models and resulted in impairment of the heat shock response.10

In this study, we hypothesized that HSP expression in MCs after acute exposure to PDF was inadequate, and searched for responsible pathways. With the aid of a combined proteomics and bioinformatics approach, we identified sterile inflammation as a candidate mechanism to explain increased susceptibility of MCs to PDF induced damage. The role of that pathway was further tested in a novel bioassay by inducing or inhibiting injury-mediated sterile inflammation. Finally, we evaluated effects of specific anti-inflammatory agents on the heat shock response of MCs exposed to PDF.

Material and Methods

Standard chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) if not specified otherwise.

Cell Culture

Immortalized human MCs (MeT-5A, ATCC CRL-9444) were maintained in 75 cm2 flasks (TPP; Techno Plastics Products AG, Trasadingen, Switzerland) with M199 culture medium (M4530, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 5.96 g/L HEPES, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin at 5% CO2 and 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. Medium was changed every other day. When confluent, cells were passaged by trypsinization to 6-well plates (TPP) for the experiments.

Experimental Design

MCs near confluence were exposed to a commercially available glucose-monomer/acidic lactate-based PDF (CAPD2; Fresenius, Bad Homburg, Germany) or sham medium changes using M199 culture medium as the control. After the exposition for 0.5 to 4 hours, cells were rinsed briefly with Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma) and subsequently kept in culture medium for a recovery period of 16 hours. All incubation periods were carried out at 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. To assess cell viability lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was determined using the TOX-7 assay kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

A series of experiments was carried out to evaluate the role of sterile inflammation in the in vitro model of PD. Necrotic cell material (NCM) was obtained from cell culture wells by mechanic homogenization of MCs in regular M199 growth medium. Cells grown in adjacent wells were pre-incubated with NCM for 24 hours before the standard PDF exposure experiments (1 hour PDF – 16 hours recovery) or sham treatment was carried out as the control. For the experiments with blockage of specific receptors, the pre-incubation medium, the NCM containing medium (if applicable), the PDF and the control medium were supplemented either with 100 μg of the tumor necrosis factor-α-mab (TNF-α-mab) infliximab (Remicade, Centocor Ortho Biotech, Horsham, PA) per milliliter of medium, or with 500 ng of the IL-1Ra anakinra (Kineret, Biovitrum AB, Stockholm, Sweden) per milliliter of medium. Medium supernatants from the recovery phase were collected and analyzed for secretion of the interleukins IL-6 and IL-8 using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (IL-6, eBioscience, San Diego, CA; IL-8, Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria).

Flow Cytometry

The modality of cell death of MCs after PDF exposure was assessed using the Apoptosis Detection Kit II (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Exposure to ultraviolet light (254 nm) was used as the positive control for induction of apoptosis. The recovery time after the exposure to PDF or sham treatment as the control was 2 hours for optimal assessment of apoptotic cell death. Measurements were carried out on a fluorescent-activated cell sorting flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson). Statistical analysis of the obtained data was performed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc. Ashland, OR) and SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Protein Sample Preparation

Cells were washed three times (250 mmol/L sucrose, 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7) and lysed by incubation with 1-mL lysis solution (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]−1-propanesulfonate [CHAPS], 10 mmol/L DTT, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% Pharmalyte 3–10 [GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden], 1 tablet of complete protease inhibitor [Roche, Basel, Switzerland] per 100 mL) per 3 × 107 cells for 45 minutes at 25°C. The resulting lysates were centrifuged for 30 minutes (14,000 × g, 10°C) and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until further processing. Total protein concentration of the samples was evaluated using the 2D-Qant kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's manual.

Quantification of Cytokine Release Into the Supernatant

Following PDF exposure as well as NCM treatments we performed analysis of the secretion of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 into the supernatant during the recovery phase. The supernatants were removed and immediately cooled on ice. Aliquots used for the assessment of LDH release were stored separately from aliquots used for cytokine assessment to avoid repeated thawing of the samples. The cytokines were measured using dedicated ELISA kits (IL6: eBioscience, San Diego, CA; IL-8: Bender MedSystems GmbH, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Western Blotting

Equal amounts of protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, on a Bio-Rad Criterion cell using Criterion precast 12.5% Tris-HCl gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) of 1-mm thickness. Proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes immediately after the run by tank blotting using a Criterion blotting cell (Bio-Rad) and the according transfer buffer (200 mmol/L glycine, 25 mmol/L Tris base, 0.1% SDS, 20% methanol). The membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in Tris Buffered Saline with Tween 20 and then incubated with the primary antibody [Hsp72 (HSPA1), SPA-810, Stressgen/Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI; β-Tubulin, # 691261, MP Biochemicals, Solon, OH] for 16 hours. After incubation with secondary, peroxidase-coupled antibodies (Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-Mouse Ig/HRP P0260, Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA) detection was accomplished by using enhanced chemiluminescence solution (Western Lightning reagent, Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA), and a ChemiDoc XRS chemiluminescence detection system (Bio-Rad). The densitometric quantification of 1D bands was accomplished using the Bio-Rad QuantityOne software.

Statistical Tests

Statistical analysis of the data obtained from ELISA and western blotting experiments was performed using SPSS 16. Values from different groups were compared using t-tests or analysis of variance where appropriate with a minimum level of P < 0.05 for significance. In case of analysis of variance Tukey's HSD was used as posthoc test. To account for the requirements of statistical testing for non-parametrically distributed data, especially in the proteomics sections, significance was validated using a Wilcoxon 2-sample test for these data.

Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE) was performed using total protein from cell lysates of MCs following the workflow described recently.4 In brief, samples were concentrated and desalted using a modified methanol/chloroform precipitation, reconstituted with solubilization buffer [7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 30 mmol/L Tris/HCl pH 8.5, 1 tablet of Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor (Roche) per 100 mL] and left at 4–8°C overnight. Total protein amounts of 300 μg per IPG strip (Immobiline DryStrip pH 3–10, linear, 18 cm, GE Healthcare) were applied by rehydration loading using a final volume of the rehydration mix of 340 μL and a rehydration time of 16 hours. Isoelectric focusing was accomplished on a Multiphor II (GE Healthcare) electrophoresis unit by gradually increasing the voltage to 3500 V and a constant phase for another 5.5 hours. The strips were consecutively incubated for 2 × 15 minutes in 10-mL equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 2%w/v SDS, 25%w/v glycerol, 3.3%v/v 50 mmol/L Tris/HCl buffer pH 8.8, stained with bromphenol blue) first supplemented with 100 mg of DTT and then with 480 mg of 2-iodoacetamide. The second dimension SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out on Multiphor II electrophoresis units at 20°C using “Excelgel XL 12-14” ready cast gels (GE Healthcare) at 100 V, 25 mA, 30 W for 60 minutes in the first phase and 800 V, 40 mA, 50 W for 3 hours in the second phase. After the first phase the IPG strip was removed and the anodic buffer strip was moved to the position of the removed IPG strip. The run was stopped when the bromphenol blue stain reached the front of the cathodic buffer strip. The protein spots were visualized using Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining and the gels were scanned on an Imagescanner II (GE Healthcare) at 300 dpi, 16 bit gray-scale. Spot quantification was carried out using the Delta2D 3.6 software (Decodon GmbH, Greifswald, Germany) based on normalized relative spot volume (percent volume) on groupwise warped images.

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

Tryptic in-gel digestion of the excised protein spots was performed following the Shevchenko standard protocol with slight modifications.11 Gel plugs were excised with a scalpel, washed with water, water/acetonitrile (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 50 mmol/L NH4HCO3 buffer/acetonitrile, altogether eight times. Afterward the proteins in the gel plugs were reduced by adding a 10 mmol/L solution of dithiothreitol (in 50 mmol/L NH4HCO3 buffer) and incubating for 45 minutes at 56°C and then alkylated by adding a 55 mmol/L solution of iodoacetamide (in 50 mmol/L NH4HCO3 buffer) and incubating over 30 minutes at 25°C in the dark. The proteins were digested with a 12.5 ng/μl solution of trypsin in 50 mmol/L NH4HCO3 buffer at 37°C overnight. The cleaved peptides were eluted from the gel pieces with 50 μl of 25 mmol/L NH4HCO3 buffer (pH 8.5), 50 μl of 5% formic acid (Merck) and 50 μl 1:1 mixture of these solutions with acetonitrile. The pooled eluates were dried by vacuum centrifugation. Then the peptides were re-dissolved with 10 μl 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and sonicated briefly. The obtained solution was desalted by use of ZipTip columns (Millipore, Billerica, MA) containing C18 material.

MS and MS/MS analyses were performed on a MALDI TOF-TOF instrument (4700 Proteomics Analyzer; Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA) which was equipped with a Nd:YAG laser (355 nm). For MS experiments the acceleration voltage was 20 kV, for MS/MS 8 kV. The collision gas was N2. As the matrix α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was used at a concentration of 10 mg/mL in acetonitrile/0.1% TFA (3:2). On-target elution with μ-C18 ZipTips was performed. Mass accuracy was ± 50 ppm, 1 missed cleavage site was allowed. Finally, a combined search (MS + MS/MS) was performed using the software MASCOT with the Swiss-Prot database. Known masses of contaminating keratin and autodigestion products of trypsin were excluded from the searches. Calibration for the spectra was done by a solution of external peptide standards.

Bioinformatics Procedures

The core data set for performing bioinformatics analysis of the proteomic data were given by the list of identified proteins showing statistically significant difference in abundance (primary candidates), represented by all proteins in Supplementary Table S1 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Significance was derived by applying a t-test for comparing the distribution of intensities of matched spots for the control group and PDF stressed group (P < 0.05).

A bioinformatics expansion of the experimentally derived protein list was performed.4,12 Studying the putative interactions between candidates, and based thereon allowing a functional interpretation of their relevance in the context of cell stress, we generated protein interaction networks (PIN) using the Online Predicted Human Interaction Database (OPHID).13 OPHID provides information on interactions of the type protein A interacts with protein B. Processing a given candidate list (A, B, … , N) with OPHID results in a set of undirected graphs representing the interactions between the candidates. To enhance the data set for bioinformatics analysis, we extracted next neighbors of our primary candidates from the PIN and added these secondary candidates.14 A next neighbor X in the PIN is defined as A-X-B, where A and B are members of the primary candidate list, and X links A and B following the interaction data as given in OPHID.

For deriving a categorization of candidates in terms of biological processes and pathways we used the PANTHER classification system.15 Next to a contextual grouping of a given protein list, PANTHER provides information on enrichment or depletion of given proteins with respect to distinct processes or pathways by computing a χ2 test (with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing) comparing the number of candidates belonging to a process or pathway and the total number of proteins assigned to this process or pathway as given by the PANTHER classification.

Results

Responses of MCs to PDF Stress

Cellular viability, monitored by release of LDH, and expression of heat shock protein 72 (Hsp72) were evaluated after exposure of MCs to PDF (CAPD2). It becomes obvious that insults caused by PDF triggers the mesothelial heat shock response. Although expression of Hsp72 rises above control level in early time points when LDH release is still low, Hsp72 levels rapidly drop with increasing exposure times, associated with exacerbated mortality of MCs. The results shown in Figure 1 suggest an inadequate cellular heat shock response to PDF stress, leading to increased cell death potentially resulting from insufficient levels of Hsp72.

Figure 1.

PDF induces insufficient levels of HSP. Expression of Hsp72 as assessed by Western blot analysis and LDH release as a parameter for cellular damage over various exposure times. Hsp72 is shown in values normalized to the expression of β-tubulin to compensate for a potential decrease in cell number with increasing PDF exposure time and relative to control. Control samples underwent sham treatment with normal growth medium. The recovery time was 16 hours for all samples. Mean values are presented as percent-fraction of the observed maximum and were computed from three independent biological experiments with three biological replicates each (n = 9 per data point). LDH release of control samples was set to 0%. The error bars represent the standard error. Expression of Hsp72 dropped below the detection range (n.d.) in case of 4-hour exposure to PDF.

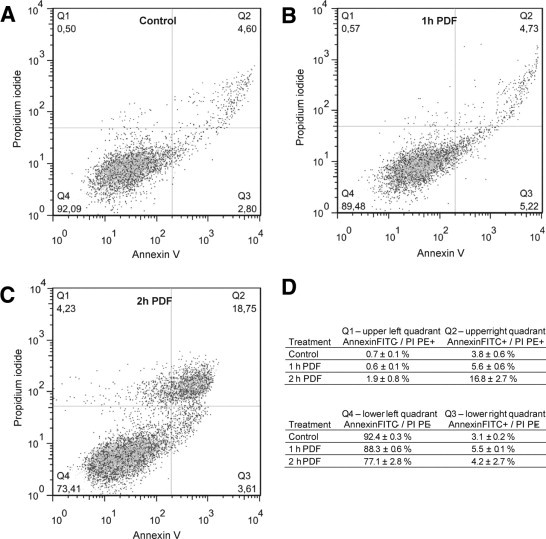

The modality of cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry. The results of propidium iodide/AnnexinV-fluorescein isothiocyanate double staining following PDF exposure or sham treatment are representative for a number of non-lethal (60 minutes) and lethal PDF exposure (120 minutes) and recovery (2 hours) times (Figure 2, A-C). Quantification of quadrant populations shows only a marginal shift to the lower right quadrant on exposure to PDF (Figure 2D). The absence of Annexin V positive viable cells, representing the apoptotic population, leads to the conclusion that the majority of non-viable MCs underwent necrotic cell death following acute exposure to pure PDF.

Figure 2.

Modality of cell death in experimental PD. Results from flow cytometry experiments after exposure of MCs to control medium (A) or PDF (B, C). The modality of cell death was assessed using standard propidium iodide (y axis) and AnnexinV-fluorescein isothiocyanate (x axis) labeling. Thresholds were set according to an unstained control (not shown) and applied to all samples as shown in the representative panels. The mean values and standard deviations of quadrant populations presented in D were computed from three independent biological experiments. PI, propidium iodide; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

To investigate the mechanisms of cell deterioration a proteomics experiment was carried out at the sublethal exposure time of 60 minutes. When the proteome of PDF stressed MCs was compared to a control cell proteome, 101 protein spots were found significantly altered (P < 0.05) in 5 “control” versus 5 “PDF stressed” gels. Robot-assisted picking of these proteins spots led to 53 successful identifications with 49 unique proteins shown in Figure 3A. The complete list of all identified protein spots is given in Supplementary Table S1 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 3.

Proteomics and bioinformatics approach. A: A representative Coomassie brilliant blue stained two-dimensional electrophoresis gel of the proteome of MCs. Proteins were separated by isoelectric point (pI) in the first dimension and molecular weight (MW) in the second dimension. Spots with significantly altered abundance (P < 0.05), where proteins could be identified by MS, are marked with arrows and labeled by Swiss-Prot identifiers according to Table 1 (“human” omitted). B: Representation of the PIN resulting from the expanded primary candidate list on the basis of OPHID interaction data. Proteomic (primary) candidates are depicted using black circles and next neighbors (secondary candidates) are depicted using light gray triangles, the lines denote the interaction edge.

For the analysis of pathways the number of proteins accessible in 2DGE experiments can by no means be regarded as complete, as low abundant or membrane-bound proteins as well as proteins which are not differentially expressed in their mode of action are hardly detected by this method. Therefore information on protein-protein interactions were obtained from the OPHID database. Of the 49 primary candidates (MS identified proteins showing significantly different abundance (P < 0.05) in the two-dimensional gels), 11 were not listed in OPHID. Expanding this candidate list of the remaining 38 proteins represented in OPHID by using the next neighbor approach resulted in additional 55 proteins (secondary candidates), giving a cumulative number of 93 candidates in total (see Supplementary Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The PIN resting on this list was a large subgraph holding 80 protein nodes and 216 protein interactions. The remaining 13 candidates were found in one additional subgraph, or did not show interactions.

Certainly, next neighbor expansion is prone for generating larger subgraphs. To test the impact of this effect, we computed the mean number of protein nodes of the largest subgraphs derived on the basis of 100 randomly selected lists of 38 proteins, each expanded by their respective next neighbors. This procedure resulted in a mean number of 21.8 nodes (SD 14.5), significantly lower (P < 0.05) than the number of protein nodes of the largest subgraph derived on the basis of the actual list of our candidates, indicating an increased functional interplay of these proteins. In particular two proteins, namely Hsp72 (Swiss-Prot accession HSP71_HUMAN) and the glucose regulated protein Grp78 (GRP78_HUMAN) form strong hubs in the largest subgraph, showing 28 protein edges each as shown in Figure 3B.

On the basis of the expanded protein list we identified involvement of 19 of the MS-identified proteins in significantly enriched (P < 0.05) processes or pathways using the PANTHER classification system. The list of these proteins and the expression profiles of the associated protein spots are given in Table 1 along with assignment to enriched processes.

Table 1.

Identified Proteins Involved in Significantly Enriched Biological Processes

| Coefficient variation (%)⁎ |

Student's t-test |

Wilcoxon 2-sample test |

Coefficient variation (%)⁎ |

Student's t-test |

Wilcoxon 2-sample test |

PANTHER process |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Name | Ratio PDF† | Group control | Group PDF | P value PDF‡ | Sig. level PDF§ | Ratio anakinra¶ | Group PDF | Group PDF + anakinra | P value anakinra† | Sig. level anakinra§ | Number of peptides∥ | Mascot score⁎⁎ | MR†† | pI‡ | Swiss-Prot entry name | SwissProt prim. acc. no. | NCBI acc. no | Immunity and defense | Stress response | Protein complex assembly | Protein folding | Protein metabolism and modification |

| Heat shock 70-kDa protein 1 | 1.43 | 12 | 12 | 0.0020 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 19 | 18 | 0.072 | 0,05 | 26 | 1000 | 70280.1 | 1000 | 70280.1 | 5.48 | HSP71_HUMAN | P08107 | 3303 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 78-kDa glucose-regulated | 1.37 | 6 | 4 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 1.44 | 20 | 12 | 0.004 | 0005 | 5 | 102 | 72505.5 | 102 | 72505.5 | 5.07 | GRP78_HUMAN | P11021 | 3309 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Heat-shock protein beta-1 | 1.34 | 7 | 7 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.47 | 11 | 23 | 0.000 | 0005 | 5 | 260 | 22825.5 | 260 | 22825.5 | 5.98 | HSPB1_HUMAN | P04792 | 3315 | 1 | 1 | |

| Heat-shock protein beta-1 | 0.65 | 22 | 11 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 1.18 | 7 | 10 | 0.017 | 0,01 | 8 | 267 | 22825.5 | 267 | 22825.5 | 5.98 | HSPB1_HUMAN | P04792 | 3315 | 1 | 1 | |

| 150-kDa oxygen-regulated protein | 1.44 | 12 | 9 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.95 | 25 | 27 | 0.753 | 5 | 103 | 111494.3 | 103 | 111494.3 | 5.16 | HYOU1_HUMAN | Q9Y4L1 | 10525 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | 0.81 | 13 | 6 | 0.023 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 82 | 36 | 0.380 | 9 | 388 | 18229 | 388 | 18229 | 7.68 | PPIA_HUMAN | P62937 | 5478 | 1 | |||

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | 0.7 | 19 | 11 | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.82 | 78 | 55 | 0.663 | 3 | 182 | 12639.3 | 182 | 12639.3 | 7.74 | MIF_HUMAN | P14174 | 4282 | 1 | |||

| Calreticulin | 1.17 | 10 | 5 | 0.019 | 0.05 | 1.29 | 11 | 15 | 0.016 | 0025 | 11 | 323 | 48282.9 | 323 | 48282.9 | 4.29 | CALR_HUMAN | P27797 | 811 | |||

| FK506-binding protein 1A | 0.64 | 11 | 12 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 2 | 65 | 12000.1 | 65 | 12000.1 | 7.88 | FKB1A_HUMAN | P62942 | 2280 | ||||||||

| Small glutamine-rich tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein | 0.57 | 13 | 49 | 0.055 | 0.05 | 1.12 | 17 | 31 | 0.491 | 5 | 223 | 34269.8 | 223 | 34269.8 | 4.81 | SGTA_HUMAN | O43765 | 6449 | ||||

| Elongation factor 2 | 1.78 | 48 | 18 | 0.027 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 38 | 42 | 0.006 | 0005 | 10 | 173 | 96219.3 | 173 | 96219.3 | 6.41 | EF2_HUMAN | P13639 | 1938 | |||

| Ubiquitin | 1.6 | 27 | 27 | 0.045 | 0.05 | 2.17 | 58 | 46 | 0.047 | 0,05 | 3 | 96 | 8559.6 | 96 | 8559.6 | 6.56 | UBIQ_HUMAN | P62988 | 7311 | |||

| Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c reductase complex core protein | 1.38 | 22 | 7 | 0.013 | 0.05 | 1.38 | 77 | 32 | 0.368 | 4 | 92 | 48583.9 | 92 | 48583.9 | 8.74 | UQCR2_HUMAN | P22695 | 7385 | ||||

| Cytosol aminopeptidase | 1.27 | 14 | 7 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.81 | 22 | 35 | 0.269 | 18 | 516 | 56530 | 516 | 56530 | 8.03 | AMPL_HUMAN | P28838 | 51056 | ||||

| NEDD8 precursor | 0.66 | 18 | 27 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 2 | 75 | 9066 | 75 | 9066 | 7.98 | NEDD8_HUMAN | Q15843 | 4738 | ||||||||

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 | 0.43 | 26 | 34 | 0.01 | 0.025 | 1.38 | 23 | 24 | 0.061 | 0,05 | 10 | 602 | 37987.1 | 602 | 37987.1 | 6.66 | PCBP1_HUMAN | Q15365 | 5093 | |||

| Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c reductase complex core protein 2 | 0.41 | 24 | 43 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 1.38 | 77 | 32 | 0.368 | 5 | 306 | 48583.9 | 306 | 48583.9 | 8.74 | UQCR2_HUMAN | P22695 | 7385 | ||||

| Protein disulfide-isomerase | 1.12 | 5 | 6 | 0.018 | 0.01 | 1.16 | 14 | 7 | 0.051 | 0,05 | 11 | 380 | 57453.7 | 380 | 57453.7 | 4.73 | PDIA1_HUMAN | P07237 | 5034 | |||

Proteins are assigned to their biological processes as obtained from the PANTHER database.

‡‡Calculated pI of the polypeptide as obtained from Swiss-Prot database. Proteins indicated as bold rows were found in significantly altered between treatment of MC with PDF and PDF supplemented with anakinra.

Coefficient variation: Relative standard deviation in percent of the quantification data within the given groups.

Ratio PDF: fold-change of spot abundance of significantly altered PDF-stressed cells versus control cells in the initial experiment.

The column contains the P value of the t-test comparing the respective groups (control versus PDF group n = 5 per group; PDF versus PDF containing anakinra group n = 6 per group).

The column contains the level of significance of the Wilcoxon 2-sample test for the respective groups with an identical n per group as mentioned before (P value less than the given number).

Ratio anakinra: fold-change of spot abundance of cells treated with PDF containing anakinra versus PDF-stressed cells.

Number of peptides matching in the peptide mass fingerprint based identification.

Mascot protein score: obtained from the combined (MS+MS/MS data) database search.

Relative molecular mass of the protein as calculated from the amino acid sequence of the polypeptide without any co- or posttranslational modifications.

The results on the pathway level are given in Table 2. Proteomic pathway analysis suggests involvement of apoptotic and inflammatory pathways in the mesothelial stress response to PDF stress.

Table 2.

Significantly Enriched Pathways after Next Neighbor Expansion

| 49 Primary candidates + secondary candidates from next neighbor expansion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway | Total no.⁎ | Expected no.† | Observed no.‡ | P value§ |

| Apoptosis signaling pathway | 131 | 0.53 | 15 | 1.78E-15 |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 71 | 0.29 | 10 | 7.50E-11 |

| Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway | 315 | 1.28 | 7 | 4.40E-02 |

Total number of genes in the given pathway in the PANTHER database.

Expected number (resulting from sample size) of candidates in any random dataset.

Observed number (after next neighbor expansion) of candidates.

Bonferroni corrected P value for overrepresentation of the given pathway.

Interestingly, the apoptotic pathway became relevant due to the differential expression of mainly anti-apoptotic players, which is in accordance with our data obtained from flow cytometry. Indeed, the proteins identified by MS in the course of our 2DGE experiment, which were involved in this pathway or showed interactions with next neighbors involved in this pathway, were chaperones with known apoptosis inhibiting function, namely Grp78 and Hsp72.

The enrichment of inflammation related pathways (Toll-like receptor and chemokine, cytokine signaling pathways) in MCs seems to be a highly relevant finding, as PDF toxicity is known to induce sterile peritoneal inflammation. Based on this observation we hypothesize that sterile inflammation mediated by damaged MCs might be a key to the deleterious alterations of the heat shock response after PDF exposure.

Sterile Inflammation

To test this hypothesis we exposed MCs near confluence for 24 hours to NCM harvested from neighboring cell culture wells by mechanic homogenization. After a recovery time of 16 hours secreted interleukins (IL-6 and IL-8) were measured in the recovery supernatant. The results show sterile inflammatory stimulation of the exposed MCs with significantly elevated interleukin levels (P < 0.01 for IL-6, P < 0.05 for IL-8) relative to the untreated control, as shown in Figure 4 (white and gray bars).

Figure 4.

Necrotic cell material (NCM) induces sterile inflammation. Secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 (A) and IL-8 (B) into the medium supernatant after pre-incubation of MCs with NCM from homogenized cells as assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Mean values are shown relative to control without NCM pretreatment (white bars) and are representative for three independent biological experiments with two biological replicates each (n = 6 per data point). The error bars represent the standard error. NCM pre-treatment is shown as gray bars. Hatched bars show the effects of the addition of the IL-1Ra anakinra (single hatched) and the anti-TNF-mab infliximab (cross-hatched). Significant differences in group-wise comparisons from analysis of variance tests are indicated with brackets (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01).

To further investigate the mechanism of inflammatory stimulation as co-factor of MC injury we performed experiments using substances, which inhibit potential signaling receptors like the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra, anakinra) and a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α (infliximab). The effects of these compounds on the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 are shown in Figure 4 as shaded bars. Whereas the addition of anakinra leads to significantly lowered secretion of IL-6 (P < 0.05) and to normal levels of IL-8 compared to control, the addition of infliximab had no specific effect.

In the same PDF exposure system, where the involvement of sterile inflammation was shown on the pathway level using proteomics methods, we assessed secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 into the medium supernatant. Compared to NCM treatment we found diminished amplitudes, but a similar pattern, suggesting similar pathogenic mechanisms.

As shown in Figure 5, anakinra was again able to effectively block the sterile inflammation induced in MCs during PDF exposure, supporting the hypothesis that sterile inflammation was triggered by damaged MCs and mediated by IL-1R dependent signaling.

Figure 5.

PDF induces a pattern of pro-inflammatory interleukins similar to NCM. Secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 (A) and IL-8 (B) into the medium supernatant after exposure of MCs to PDF as assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Mean values are shown relative to control without PDF exposure (white bars) and are representative for three independent biological experiments with two biological replicates each (n = 6 per data point). The error bars represent the standard error. PDF exposure is shown as gray bars. Hatched bars show the effects of the addition of the IL-1Ra anakinra (single hatched) and the anti-TNF-mab infliximab (cross-hatched). Significant differences in group-wise comparisons from analysis of variance tests are indicated with brackets (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01).

Because the addition of anakinra demonstrated significant reduction of inflammation in MCs as well after exposure to NCM and PDF, respectively, the effect of anakinra on the viability (LDH release) and the heat shock response (Hsp72 expression) was evaluated in a time-course experiment. Figure 6 shows the systematic effect of anakinra on MC viability and the heat shock response. The addition of anakinra delays cellular damage significantly (P < 0.05 at 1, 2, and 3 hours of exposure time). As soon as cellular damage occurs despite the addition of anakinra, the expression of Hsp72 is maintained at significantly higher levels (P < 0.05 at 2 and 3 hours of exposure time).

Figure 6.

Addition of anakinra enables higher expression of Hsp72. The graph shows the results of a time-course experiment with PDF (black bars) or PDF supplemented with the IL-1Ra anakinra (shaded bars). Control samples underwent sham treatment with normal growth medium. Data are representative for three independent biological experiments with two biological replicates each (n = 6). Bars represent mean values relative to control; error bars are shown as standard error. A: LDH release was assessed after various exposure times. Enzymatic measurements were carried out in the supernatant after a recovery of 16 hours. B: Hsp72 was assessed by Western blot from total protein lysates after a recovery of 16 hours. Values are normalized to the expression of β-tubulin to compensate for a potential decrease in cell number with increasing PDF exposure time. Asterisks indicate time-points with significant differences in pair-wise comparisons between PDF and PDF supplemented with anakinra (t-test; P < 0.05).

Finally, we investigated the mode of action of anakinra-mediated protection of MCs against PDF exposure in our proteomics model. Proteins with known association to PDF stress, as proven by their involvement in enriched biological processes or pathways (Table 1), were analyzed for their expression with or without the addition of anakinra to PDF using 2DGE as described before. The expression ratios of these proteins and the associated P values for a groupwise comparison are also given in Table 1.

More than 30% of these candidates revealed a significantly altered abundance (P < 0.05, expected 5%) in the gels produced from the anakinra experiment. Significant effects (P < 0.05) of anakinra on protein expression levels are visualized in Figure 7 in relation to the initial proteomics experiment.

Figure 7.

Proteomics evaluation of anakinra effects on MCs after PDF exposure. Expression profiles of proteins with known association to PDF stress after addition of the IL-1Ra anakinra to PDF. The abundance as measured from two-dimensional gel staining is given relative to control conditions of the initial experiment. All proteins presented in this graph show significant differences in spot abundance as well between control and PDF treatment as between PDF and PDF supplemented with anakinra (P < 0.05). Expression profiles are labeled with Swiss-Prot entry names as given in Table 1. The two profiles for Hsp27 (HSPB1_HUMAN) refer to two separate spots on the two-dimensional gels. Data are representative for three independent biological experiments with two biological replicates each (n = 6). Error bars represent the SE.

Discussion

In previous work, we reported that the same bioincompatible properties of PDF that induce MC injury also induce specific HSPs, which lead to repair and recovery in experimental PD.4,16,17 Consequently, the progressive peritoneal damage in the clinical setting of PD must at least, in part, be regarded as an imbalance between cellular injury and cytoprotective processes following cytotoxic PDF exposure.

Cell Damage and Repair Patterns in Response to PDF Exposure

In the first part of this study, we related cytoprotective stress responses to cellular survival in MCs following increasingly severe PDF stress. These results confirm the ability of PDF to induce HSP but also demonstrate that the expression of HSP rapidly falls below the control level beyond a threshold of PDF stress, resulting in severe exacerbation of cell death. This inadequately low HSP expression might be either passively caused by accidental cell death or actively induced by cellular reprogramming. Whereas the former cell fate can only be improved by decreasing PDF cytotoxicity, the latter fate might be open to alternate interventions. Programmed cell death via the apoptosis pathway would represent the prototype active cellular pathway. In immune cells, induction of apoptotic cell death via exposure to lethal cytokines resulted in an almost complete suppression of the heat shock response, mediated by caspase-dependent processes.18 In our study, such active induction of apoptosis was not responsible for the exacerbated cell death, as demonstrated by the almost complete absence of apoptosis markers in the fluorescent-activated cell sorting analysis. Similar results have been previously reported in omental-derived MCs following acute exposure to undiluted PDF.19 Together with the abrupt increase in LDH release, our data indicate alternate cellular processes that sensitize MCs to PDF exposure beyond the threshold. Combined cytotoxic insults and counteracting cellular reactions likely involve complex, interdependently regulated molecular mechanisms.20,21

The systems biology approach using proteomics and bioinformatics is particularly well suited to investigate such complex interplay of cellular responses.12 With this approach we could recently determine that acute PDF exposure leads to reduction of unspecific biological processes in favor of the MCs' response to stress including mechanisms for repair, cell structure modification, signal transduction, and carbohydrate metabolism.4,5 Enriched biological processes also confirmed cytoskeletal damage, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and cellular remodeling as mechanisms mediating MC injury. In our present study, we applied specific pathway analysis using a bioinformatically expanded list of proteomics candidates.12 Pathway analysis is a tool to validate the biological relevance of the experiment and to eliminate the fraction of false-positive candidates in every “omics” experiment before further interpretation.4 Our results demonstrate simultaneous activation of apoptosis-related pathways and inflammation during recovery of MCs from PDF exposure via database queries of the identified proteins. These data corroborate previous studies that have described apoptotic changes in MCs following either exposure to lethal cytokines, to toxic glucose degradation products, or to PDF in modified PDF exposure systems using Transwell culture apparatus.22–24 However, the acute exposure and recovery model used in the present study is not ideal for studying apoptosis in MCs but had been established for the investigation of cellular stress responses and short-term repair mechanisms.4,6–8 In this setting, the PDF exposure time chosen for the proteomics experiments has previously been shown to be sublethal, and our fluorescent-activated cell sorting results also revealed an almost absent rate of cell death.7 Accordingly, the spectrum of identified proteins was predominantly anti-apoptotic, reflecting an equilibrium of protective and lethal processes in PDF stressed MCs, which has also been observed in related models.25 Hsp72 was reported to counteract apoptosis by inhibition of oligomerization at the level of the apoptosome, by inhibition of translocation of the apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) to the nucleus and by negative interaction with JNK.26,27 Hsp27 is known to suppress apoptosis by Fas/FasL interaction.28 Less is known about the distinctive modes of action of the molecular chaperones Grp78 and HYOU1 (Orp150) although both show anti-apoptotic potential in other model systems.29,30

Potential Role of Inflammatory Processes

Peritoneal MCs are known to express cytokines and adhesion molecules, when stimulated.31,32 Our data revealed involvement of novel players like HSPs that can be assigned to immunity and defense processes, FK-binding protein (FKB1A), cyclophilin A (PPIA), and migration inhibitory factor (MIF). FKB1A and PPIA are members of the immunophilin family and are better known as receptors for the immunosuppressive drugs tacrolimus and cyclosporine.33 MIF represents a constitutively expressed cytokine that promotes transcription and translation of immune and inflammatory genes by inhibition of degradation of specific mRNA and transcription factors.34

Chronic peritoneal exposure to PDF has been suspected to be associated with sterile inflammatory processes.9 The danger model (injury-induced inflammation)35 suggests sensing of cellular injury by MCs with subsequent induction of peritoneal sterile inflammation: indeed, extracts from NCM, used as danger signals, recently induced cytokine and chemokine production in MCs via membrane-bound IL-1 receptor (IL-1R).36 IL-1R signals through a conserved intracellular region, termed the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain, representing a relevant overlap with TLR and TNF signaling pathways.37,38

Cell Damage and PDF Exposure Induce Inflammatory Signaling via IL-1R

In the next part of this study, we adapted the experiments from Eigenbrod et al36 by substituting NCM from macrophage and liver cell extracts with extracts from MCs. In this approach, exposure of normal MCs to injured MCs (using MC-derived NCM as surrogate for ambient cell injury) induced sterile inflammation, which resulted in elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8. The addition of anakinra led to a marked reduction of these inflammation markers. The drug anakinra is a recombinant polypeptide that represents a shortened isoform analog of the human IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra). The biological activity of anakinra derives from its ability to competitively inhibit IL-1 binding to the IL-1R.39 In contrast, addition of a monoclonal antibody against human TNF-α (infliximab) did not alter the elevated levels of IL-6 or IL-8 after NCM exposure. This ineffective inhibition of inflammation by blocking TNF-α likely reflects the absence of this ligand in the pure MC-derived NCM used for the stimulation experiments. Certainly, TNF-α and other relevant cytokines play a relevant role in intercellular peritoneal cross talk and in MC fate in more complex models of the in vivo situation of PD and peritonitis.25 However, our data provide clear evidence for IL-1R–mediated inflammation in MCs following NCM exposure.

Based on this model, we searched for evidence whether IL-1R-dependent cellular signal transduction is also responsible for the activation of inflammatory pathways in MCs following PDF exposure. Although sublethal, the chosen PDF stress caused sufficient MC damage to result in the release not only of intracellular LDH but also of danger signals into the supernatant. Similar to the artificial addition of NCM, PDF was able to induce sterile inflammation as evidenced by elevated levels of IL-6 and IL-8. Again, the addition of anakinra led to a substantial reduction of these inflammation markers, demonstrating that endogenous ligands of the IL-1R were responsible for the activation of pro-inflammatory signaling in experimental PD.

Cytokine Receptor Antagonists Might Be Used as Potential Cytoprotective Agents

In the final part of this study, we related sterile inflammation to increased susceptibility of MCs to PDF cytotoxicity. The addition of anakinra indeed resulted in cytoprotection of MCs, as demonstrated by markedly reduced MC damage with blockade of sterile inflammation. PDF exposure times could be doubled for equal amounts of cell death. LDH release following standard exposure of 1 hour was completely normalized to control levels. These findings clearly indicate that IL-1R–mediated signal transduction sensitized MCs to PDF cytotoxicity. The clinical relevance of this novel pathomechanism was recently pointed out in a peritonitis model, where high levels of pro-inflammatory ligands in PD effluents could also be blocked specifically by IL-1b antibodies.40 It has been previously shown that pro-inflammatory stimuli sensitize human cells to subsequent insults, exacerbating cellular death.41 This phenomenon has been called the heat shock paradox.42 Although the inflammatory stimulus in these experiments consisted of lipopolysaccharide-mediated Toll-like receptor signaling, this signaling pathway is known to overlap with the IL-1R pathway via the TIR domain, suggesting that IL-1 and LPS might induce a common effector mechanism that sensitize cells to subsequent stress.

To further deepen our understanding of molecular mechanisms responsible for cytoprotection by reduced cellular inflammation, we analyzed effects of anakinra on expression of proteins involved in relevant biological processes during recovery from PDF. A third of the re-detected proteins demonstrated a significantly altered abundance (p < 0.05) in the anakinra experiment, indicating the relevance of one or several of these players in this phenomenon. The major subgroup of proteins that were increased following blockade of IL-1R consisted of cytoprotective molecular chaperons such as Hsp27 (HSPB1), Grp78, and calreticulin.43 Grp78 and calreticulin are endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins and are expected to be up-regulated by the glucose-based PDF.17,44 It is conceivable that IL-1R signaling results in a dampening of these effectors of the cellular stress response, and that this dampening (heat shock paradox-like phenomenon) could be released by the addition of anakinra. The differential abundance of two Hsp27 isoforms are caused by altered phosphorylation of this actin-binding chaperon, most likely due to known anakinra effects on p38 activation.45 Additional altered proteins are involved in protein synthesis (eEF2) and protein degradation (ubiquitin). These proteins have not previously been associated with IL-1R-mediated signaling but likely reflect the general effects of reduced inflammation, such as improved protein turnover. A recent transcriptomics study comparing the global genomic response to cells subjected to heat shock or LPS stress has also demonstrated overlapping expression patterns between these stimuli in a subset of genes that has functional annotation to chemokine related biology, including IL-1, supporting indirectly our data in the PDF exposure model.46

In summary, this new concept of PDF stress allows to delineate the deleterious effect of sterile inflammation in MCs after exposure to cytotoxic PDF (Figure 8). Danger signals, released from injured MCs, lead to an elevated level of cytokine release associated with sterile inflammation via IL-1R-mediated pathways. This sterile inflammation reduces expression of cytoprotective chaperones and exacerbates MC damage on PDF exposure. Our findings, based on proteomics and bioinformatics techniques as well as confirming standard techniques, raise the possibility that agents that block the actions of IL-1 might be useful in limiting peritoneal damage during PD.

Figure 8.

New concept of peritoneal dialysis fluid (PDF) stress. Scheme of mesothelial cell monolayer exposed to peritoneal dialysis PDF. The current model of cytotoxic damage is extended with the model of sterile inflammation, which is revealed by pathway analysis and confirmed in experiments simulating sterile inflammation. Danger signals, released from injured cells, lead to sterile inflammation in adjacent cells via IL-1 receptor (IL-R)-mediated pathways. This sterile inflammation affects cytoprotective responses and exacerbates cell death on PD fluid exposure.

Footnotes

Supported by the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung (C.A.) and by the FWF (Austrian Science Fund) Project P18130-B13 (C.A.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.034.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Topley N., Kaur D., Petersen M.M., Jorres A., Williams J.D., Faict D., Holmes C.J. In vitro effects of bicarbonate and bicarbonate-lactate buffered peritoneal dialysis solutions on mesothelial and neutrophil function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:218–224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V72218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorres A., Bender T.O., Finn A., Witowski J., Frohlich S., Gahl G.M., Frei U., Keck H., Passlick-Deetjen J. Biocompatibility and buffers: effect of bicarbonate-buffered peritoneal dialysis fluids on peritoneal cell function. Kidney Int. 1998;54:2184–2193. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witowski J., Topley N., Jorres A., Liberek T., Coles G.A., Williams J.D. Effect of lactate-buffered peritoneal dialysis fluids on human peritoneal mesothelial cell interleukin-6 and prostaglandin synthesis. Kidney Int. 1995;47:282–293. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kratochwill K., Lechner M., Siehs C., Lederhuber H.C., Rehulka P., Endemann M., Kasper D.C., Herkner K.R., Mayer B., Rizzi A., Aufricht C. Stress responses and conditioning effects in mesothelial eells exposed to peritoneal dialysis fluid. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1731–1747. doi: 10.1021/pr800916s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lechner M., Kratochwill K., Lichtenauer A., Rehulka P., Mayer B., Aufricht C., Rizzi A. A proteomic view on the role of glucose in peritoneal dialysis. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2472–2479. doi: 10.1021/pr9011574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbeiter K., Bidmon B., Endemann M., Bender T.O., Eickelberg O., Ruffingshofer D., Mueller T., Regele H., Herkner K., Aufricht C. Peritoneal dialysate fluid composition determines heat shock protein expression patterns in human mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1930–1937. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidmon B., Endemann M., Arbeiter K., Ruffingshofer D., Regele H., Herkner K., Eickelberg O., Aufricht C. Overexpression of HSP-72 confers cytoprotection in experimental peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2300–2307. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endemann M., Bergmeister H., Bidmon B., Boehm M., Csaicsich D., Malaga-Dieguez L., Arbeiter K., Regele H., Herkner K., Aufricht C. Evidence for HSP-mediated cytoskeletal stabilization in mesothelial cells during acute experimental peritoneal dialysis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F47–F56. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00503.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flessner M.F. Inflammation from sterile dialysis solutions and the longevity of the peritoneal barrier. Clin Nephrol. 2007;68:341–348. doi: 10.5414/cnp68341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper P.L. Insulin Signaling: GSK-3, heat shock proteins and the natural history of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a hypothesis. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2007;5:220–230. doi: 10.1089/met.2007.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perco P., Rapberger R., Siehs C., Lukas A., Oberbauer R., Mayer G., Mayer B. Transforming omics data into context: bioinformatics on genomics and proteomics raw data. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2659–2675. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown K.R., Jurisica I. Online predicted human interaction database. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2076–2082. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Platzer A., Perco P., Lukas A., Mayer B. Characterization of protein-interaction networks in tumors. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mi H., Guo N., Kejariwal A., Thomas P.D. PANTHER version 6: protein sequence and function evolution data with expanded representation of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D247–D252. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arbeiter K., Bidmon B., Endemann M., Ruffingshofer D., Mueller T., Regele H., Eickelberg O., Aufricht C. Induction of mesothelial HSP-72 upon in vivo exposure to peritoneal dialysis fluid. Perit Dial Int. 2003;23:499–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aufricht C., Endemann M., Bidmon B., Arbeiter K., Mueller T., Regele H., Herkner K., Eickelberg O. Peritoneal dialysis fluids induce the stress response in human mesothelial cells. Perit Dial Int. 2001;21:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schett G., Steiner C.W., Groger M., Winkler S., Graninger W., Smolen J., Xu Q., Steiner G. Activation of Fas inhibits heat-induced activation of HSF1 and up-regulation of hsp70. FASEB J. 1999;13:833–842. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.8.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alscher D.M., Biegger D., Mettang T., van der Kuip H., Kuhlmann U., Fritz P. Apoptosis of mesothelial cells caused by unphysiological characteristics of peritoneal dialysis fluids. Artif Organs. 2003;27:1035–1040. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2003.07222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z.G., Kim K.S., Park H.C., Choi K.H., Lee H.Y., Han D.S., Kang S.W. High glucose activates the p38 MAPK pathway in cultured human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2003;63:958–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vargha R., Bender T.O., Riesenhuber A., Endemann M., Kratochwill K., Aufricht C. Effects of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition on acute stress response in human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3494–3500. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amore A., Cappelli G., Cirina P., Conti G., Gambaruto C., Silvestro L., Coppo R. Glucose degradation products increase apoptosis of human mesothelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:677–688. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catalan M.P., Subira D., Reyero A., Selgas R., Ortiz-Gonzalez A., Egido J., Ortiz A. Regulation of apoptosis by lethal cytokines in human mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2003;64:321–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang A.H., Chen J.Y., Lin Y.P., Huang T.P., Wu C.W. Peritoneal dialysis solution induces apoptosis of mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1280–1288. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santamaria B., Benito-Martin A., Ucero A.C., Aroeira L.S., Reyero A., Vicent M.J., Orzaez M., Celdran A., Esteban J., Selgas R., Ruiz-Ortega M., Cabrera M.L., Egido J., Perez-Paya E., Ortiz A. A nanoconjugate Apaf-1 inhibitor protects mesothelial cells from cytokine-induced injury. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravagnan L., Gurbuxani S., Susin S.A., Maisse C., Daugas E., Zamzami N., Mak T., Jaattela M., Penninger J.M., Garrido C., Kroemer G. Heat-shock protein 70 antagonizes apoptosis-inducing factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:839–843. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosser D.D., Caron A.W., Bourget L., Denis-Larose C., Massie B. Role of the human heat shock protein hsp70 in protection against stress-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5317–5327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehlen P., Schulze-Osthoff K., Arrigo A.P. Small stress proteins as novel regulators of apoptosis: Heat shock protein 27 blocks Fas/APO-1- and staurosporine-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16510–16514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bando Y., Tsukamoto Y., Katayama T., Ozawa K., Kitao Y., Hori O., Stern D.M., Yamauchi A., Ogawa S. ORP150/HSP12A protects renal tubular epithelium from ischemia-induced cell death. FASEB J. 2004;18:1401–1403. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1161fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J., Lee A.S. Stress induction of GRP78/BiP and its role in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:45–54. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bender T.O., Riesenhuber A., Endemann M., Herkner K., Witowski J., Jorres A., Aufricht C. Correlation between HSP-72 expression and IL-8 secretion in human mesothelial cells. Int J Artif Organs. 2007;30:199–203. doi: 10.1177/039139880703000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jorres A., Ludat K., Lang J., Sander K., Gahl G.M., Frei U., DeJonge K., Williams J.D., Topley N. Establishment and functional characterization of human peritoneal fibroblasts in culture: regulation of interleukin-6 production by proinflammatory cytokines. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2192–2201. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7102192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J., Farmer J.D., Jr., Lane W.S., Friedman J., Weissman I., Schreiber S.L. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calandra T., Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:791–800. doi: 10.1038/nri1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eigenbrod T., Park J.H., Harder J., Iwakura Y., Nunez G. Cutting edge: critical role for mesothelial cells in necrosis-induced inflammation through the recognition of IL-1 alpha released from dying cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:8194–8198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Most R.G., Currie A.J., Robinson B.W., Lake R.A. Decoding dangerous death: how cytotoxic chemotherapy invokes inflammation, immunity or nothing at all. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:13–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C.J., Kono H., Golenbock D., Reed G., Akira S., Rock K.L. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen C.M., Faulenbach M., Vaag A., Volund A., Ehses J.A., Seifert B., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Donath M.Y. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1517–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witowski J., Tayama H., Ksiazek K., Wanic-Kossowska M., Bender T.O., Jorres A. Human peritoneal fibroblasts are a potent source of neutrophil-targeting cytokines: a key role of IL-1beta stimulation. Lab Invest. 2009;89:414–424. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y., Voegeli T.S., Liu P.P., Noble E.G., Currie R.W. Heat shock paradox and a new role of heat shock proteins and their receptors as anti-inflammation targets. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007;6:91–100. doi: 10.2174/187152807780832274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeMeester S.L., Buchman T.G., Cobb J.P. The heat shock paradox: does NF-kappaB determine cell fate? FASEB J. 2001;15:270–274. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0170hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ni M., Lee A.S. ER chaperones in mammalian development and human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3641–3651. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aufricht C. HSP: helper, suppressor, protector. Kidney Int. 2004;65:739–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uekawa N., Nishikimi A., Isobe K., Iwakura Y., Maruyama M. Involvement of IL-1 family proteins in p38 linked cellular senescence of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 2004;575:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong H.R., Odoms K., Sakthivel B. Divergence of canonical danger signals: the genome-level expression patterns of human mononuclear cells subjected to heat shock or lipopolysaccharide. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.