Abstract

Retinopathy of prematurity is a major side effect of oxygen therapy for preterm infants, and is a leading cause of blindness in children. To date, it remains unclear whether the initial microvascular obliteration is triggered by degradation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) α proteins or by other mechanisms such as oxidative stress. Here we show that prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 (PHD2), an enzyme mostly responsible for oxygen-induced degradation of HIF-α proteins, plays a major role in oxygen-induced retinopathy in mice. In neonatal mice expressing normal amounts of PHD2, exposure to 75% oxygen caused significant degradation of retinal HIF-α proteins, accompanied by massive losses of retinal microvessels. PHD2 deficiency significantly stabilized HIF-1α, and to some extent HIF-2α, in neonatal retinal tissues, and protected retinal microvessels from oxygen-induced obliteration. After hyperoxia-treated neonatal mice were returned to ambient room air, retinal vasculature in PHD2-deficient mice remained mostly intact and showed very little neoangiogenesis. These findings demonstrate a close association between PHD2-dependent HIF-α degradation and oxygen-induced retinal microvascular obliteration, and imply that PHD2 may be a promising therapeutic target to prevent oxygen-induced retinopathy.

Oxygen therapy is a significant risk factor of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), although a variety of other factors also contribute to the disease.1–3 In phase I of ROP development, premature infants may experience significant losses of retinal microvessels, which often are induced or worsened by oxygen therapy for respiratory insufficiency. In phase II, retinal tissues develop severe ischemia as a result of microvascular damage, resulting in robust retinal neoangiogenesis. Numerous aberrant microvessels are formed in phase II, which often exist as vascular tufts protruding from the inner retinal surface into the vitreous cavity. In severe cases, vascular defects eventually may result in retinal detachment and blindness.

A mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) was established by Smith et al4 that closely recapitulates many key aspects of ROP in human beings. The model entails exposure of neonatal mice to high levels of oxygen (phase I), followed by housing under normal room air (phase II). During oxygen exposure, retinal microvascular obliteration leads to large avascular areas, thus mimicking phase I of ROP development. After exiting the oxygen chamber, massive neoangiogenesis occurs in ischemic retinal tissues, leading to the formation of numerous vascular tufts.

The mechanism underlying OIR remains incompletely understood. However, one possibility is that hyperoxia triggers rapid degradation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) α subunits including HIF-1α and HIF-2α,5–7 both of which are important for the expression of angiogenic and endothelial cell survival factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A,8–9 angiopoietin (Angpt)-1,10 stromal differentiation factor (SDF)-1,11 and erythropoietin (EPO).12–13 Oxygen-dependent degradation of HIF-α subunits is mediated by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins including at least three isoforms (PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3), which also are referred to as HIF-prolyl hydroxylases or egg laying nine.14–16 PHDs use molecular oxygen as a substrate to hydroxylate specific prolyl residues in HIF-α subunits, tagging them for von Hippel-Lindau protein–dependent polyubiquitination in E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes and rapid degradation in proteasomes.17–23 Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-α subunits accumulate and translocate into the nucleus, where they form transcriptionally active heterodimers with HIF-1β.6

Although it is logical to speculate that oxygen-induced retinal microvascular obliteration may be mediated by HIF-α degradation, other mechanisms such as increased production of reactive oxygen species possibly also are involved.24–26 Thus, precise mechanisms remain to be investigated. In this study, we demonstrate that retinal HIF-α abundance is indeed diminished in neonatal mice exposed to hyperoxia, and that oxygen-induced degradation of retinal HIF-α is minimized by PHD2 deficiency. Furthermore, we present evidence that PHD2 deficiency alone is sufficient to protect retinal microvessels from oxygen-induced damages and prevent ROP-like phenotypes in mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Connecticut Health Center in compliance with Animal Welfare Assurance. Production and breeding of Phd knockout mice have been described previously.27,28 Disruption of floxed Phd2 allele was induced by daily oral gavage of tamoxifen (40 mg/kg of body mass) at postnatal day (P) 1 through P3. Approximately 25% of tamoxifen-treated Phd2f/f/Rosa26CreERT2/+ (Phd2 CKO) mice were excluded from experiments as a result of growth retardation. Studies using the mouse OIR model were performed according to Smith et al.4 The full model includes exposure of neonatal mice to 75% oxygen from P7 to P12 (phase I) and another 5 days under ambient room air (phase II, P12–P17). Variations of the full model are applied for specific purposes and are indicated where appropriate. For staging of neonatal mice, the day when a litter was born was considered P0.

Labeling of Retinal Blood Vessels by Lectins

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Racinus communis isolectin (RCA-I) (15 mg/kg body mass, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was injected into the left ventricular (LV) chamber of anesthetized mice, followed by perfusion with saline. Whole eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 minutes. Retinas were dissected, and then flat-mounted by radial incisions. Flat-mounted retinas were stained with Alexa 594–isolectin B4 (IB4; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Proliferation and Apoptosis Assays

Proliferative cells were labeled by intraperitoneal injection of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU, 120 mg/kg of body mass; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). After 1.5 hours, mice were euthanized, and whole eyes were isolated. Eyes including the attached retinas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes and stored in 70% ethanol. Retinas were isolated in PBS, incubated first in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS (30 minutes at room temperature), and then in 2 mol/L HCl (1 hour, 37°C). Subsequently, retinas were incubated with rat anti-BrdU (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) followed by Alexa Fluor 488–goat anti-rat IgG (Jackson Immunologicals, West Grove, PA). The same retinas were further stained with Alexa 594–isolectin B4 to reveal vascular structures including tufts.

Apoptotic cells were detected by Apoptag terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling staining kit (Millipore Biosciences, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Detection of Retinal Tissue Hypoxia

To label hypoxic tissues, hypoxia marker 2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3- pentafluoropropyl) acetamide (EF5; a gift from Cameron Koch, University of Pennsylvania) was injected intraperitoneally (25 mg/kg body weight). At 1.5 hours after injection, mice were perfused with saline. Whole eyes were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Retinas were dissected from fixed eyes, flat-mounted, permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100, and rinsed several times in PBS to remove unbound EF5. Bound EF5 was detected by immunofluorescence staining with Cy3-conjugated anti-EF5 (a gift from Cameron Koch, University of Pennsylvania).

Analyses of Pericyte Recruitment and Astrocyte Distribution

To visualize pericytes and astrocytes, fixed, flat-mounted retinas were incubated with anti-NG2 (Millipore Biosciences, Temecula, CA) and anti-GFAP (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA), respectively, followed by Alexa Fluor 488–goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen). Retinas were further stained with Alexa 594–IB4 and thoroughly washed with PBS.

Histology and Immunohistochemical Staining

Histological sections of retinas were prepared from 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded whole eyes. Vascular tufts were visualized by periodic acid-Schiff staining. Vascular structures including tufts also were visualized by immunohistochemical staining with rat anti-CD31 (Mec 13.3; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in conjunction with goat anti-rat IgG horseradish peroxidase.

Western Blotting

To determine the relationship between oxygen exposure and retinal HIF-α protein abundance, neonatal mice were placed in an oxygen chamber for 2 days between P7 and P9, and retinal nuclear extracts were prepared for Western blotting. To minimize re-accumulation of HIF-α proteins after mice were returned to room air, hyperoxia-treated neonatal mice were euthanized within 2 minutes after exiting the oxygen chamber, and bodies immediately were buried deep in ice. Whole eyes were removed from mice and placed in ice-cold PBS. Retinas were isolated in ice-chilled PBS, which was replaced frequently to maintain low temperatures. To prepare nuclear protein extracts, retinas were homogenized in ice-cold nuclear extraction buffer composed of 10 mmol/L HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L KCl, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.2 mmol/L deferoxamine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.1% NP-40, and 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Nuclei were collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in 20 mmol/L HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9), 420 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.2 mmol/L deferoxamine, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 25% glycerol (kept on ice). Antibodies were as follows: anti–HIF-1α (NB100-449; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO); anti–HIF-2α (NB100-122; Novus Biologicals); anti–HIF-1β (sc-5580; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-mouse PHD2, and anti–β-actin (sc-1616; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Data Quantification

Number of proliferative cells, apoptotic cells, branching points, and band intensities in Western blots were quantified with the assistance of the National Institutes of Health ImageJ program (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html). Neoangiogenesis and avascular areas were quantified with Adobe Photoshop CS4 as described by Smith et al.29 EF5-positive areas also were quantified with Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qPCR)

Total retinal RNA preparations were used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) analyses using SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA) and the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosciences). The following primers were used: Hif-1α, 5′-GCACGGGCCATATTCATGTC-3′ and 5′-CACGTCATGGGTGGTTTCTTG-3′; Hif-2α, 5′-AACGGCTCTGGTTTTGGGA-3′ and 5′-CCGTGCACTTCATCCTCATG-3′; Phd1, 5′-CATCAATGGGCGCACCA-3′ and 5′-GATTGTCAACATGCCTCACGTAC-3′; Phd2, 5′-TAAACGGCCGAACGAAAGC-3′ and 5′-GGGTTATCAACGTGACGGAC-3′; Phd3, 5′-CTATGTCAAGGAGCGGTCCAA-3′ and 5′-GTCCACATGGCGAACATAACC-3′; Vegfa, 5′-CACGACAGAAGGAGAGCAGAAGT-3′ and 5′-TTCGCTGGTAGACATCCATGAA-3′; fetal liver kinase (Flk)-1, 5′-TTTGGCAAATACAACCCTTCAGA-3′ and 5′-GCAGAAGATACTGTCACCACC-3′; Flt-1, 5′-TGGACCCAGATGAAGTTCCC-3′ and 5′-GCGATTTGCCTAGTTTCAGTCT-3′; Epo, 5′-ACTCTCCTTGCTACTGATTCCT-3′ and 5′-ATCGTGACATTTTCTGCCTCC-3′; Angpt-1, 5′-CGTCGTGTTCTGGAAGAATGA-3′ and 5′-CGTCGTGTTCTGGAAGAATGA-3′; Tie-2, 5′-CGGCCAGGTACATAGGAGGAA-3′ and 5′-TCACATCTCCGAACAATCAGC-3′; Sdf-1, 5′-GAGAGCCACATCGCCAGA-3′ and 5′-TTTCGGGTAAATGCACACTTG-3′; Cxcr-4, 5′-AGCATGACGGACAAGTAC-3′ and 5′-GATGATATGGACAGCCTTACAC-3′; endothelial nitric oxide synthase, 5′-TGAAGATCTCTGCCTCACTCATG-3′ and 5′-AGTCTCAGAGCCATACAGAATGGTT-3′; insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (Igfbp)-3, 5′-CCGAGTCTAAGCGGGAGACA-3′ and 5′-TCAGCACATTGAGGAACTTCAGA-3′; and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt), 5′-TCAGTCAACGGGGGACATAAA-3′ and 5′-GGGGCTGTACTGCTTAACCAG-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t-tests (two-tailed) were performed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Where variances were unequal between two groups in comparison, type was set to 3. Variations are presented as standard error of the mean.

Results

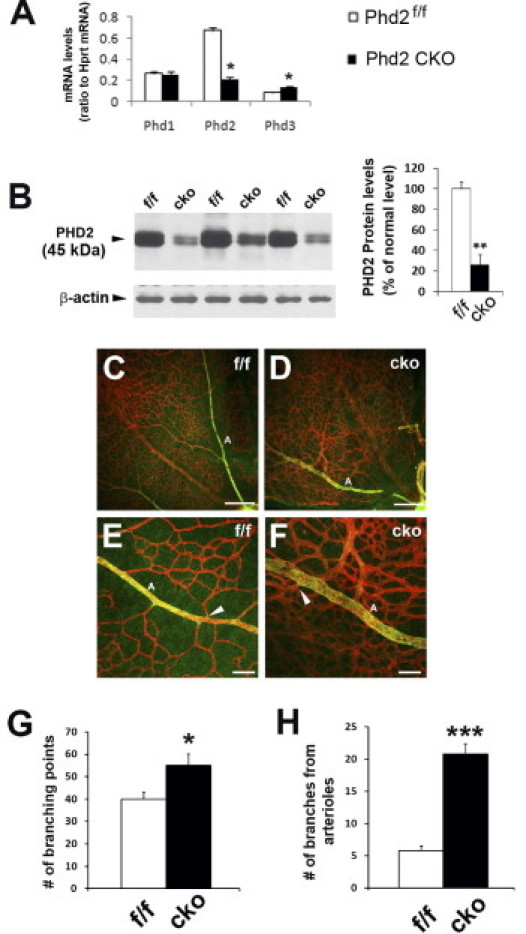

Retinal Vascular Development in PHD2-Deficient Mice

Phd2 was disrupted in neonatal mice by tamoxifen-mediated activation of Rosa26CreERT2, which was encoded by a CreERT2 complementary DNA insert at the Rosa26 locus.28 To determine knockout efficiency, we performed qPCR to compare relative Phd2 mRNA levels between tamoxifen-treated Phd2f/f/Rosa26CreERT2/+ (Phd2 CKO) and Phd2f/f mice. At P5 and P7, Phd2 mRNA levels in Phd2 CKO mice was reduced to 36% ± 4.8% (n = 4; P < 0.01) and 31% ± 3.7% (n = 6; P < 0.01) of Phd2f/f controls, respectively. The Phd1 and Phd3 mRNA levels also were quantified at P7. In Phd2 CKO mice, Phd1 mRNA was not altered, but Phd3 mRNA was increased to 154% ± 24% relative to Phd2f/f controls (n = 6; P < 0.05). Phd3 is a known target for HIF-1α, thus its increased expression as a result of PHD2 deficiency is not surprising.30–33 qPCR data at P7 are summarized in Figure 1A. At the protein level, Phd2 knockout efficiency was examined by anti-PHD2 Western blotting (P7), which demonstrated that PHD2 protein abundance was reduced significantly in Phd2 CKO retinas (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Characterization of Phd2 knockout and branching morphogenesis. Mice were treated with tamoxifen by oral gavage between P1 and P3, and euthanized at P7 for the following analyses. A: qPCR of retinal mRNA (n = 6 mice for each group). *P < 0.05. Phd2 CKO, tamoxifen-treated Phd2f/f/Rosa26+/CreERT2. B: Anti-PHD2 Western blotting of retinal protein extracts (n = 3 mice in each group). **P < 0.01. C and D: Alexa 594–IB4 staining of flat-mounted retinas. Images are oriented with the optic nerve head at the lower right corners. Scale bars = 200 μm. E and F: Arterial branches and flanking areas. A, arterial branches; arrowheads are pointed to examples of branching points. Scale bars = 50 μm. G: Quantification of branching points per 0.04-mm2 area. Areas selected for counting were located approximately midway between the optic nerve head and periphery, and were at least 50 μm away from large vascular branches, especially arterial branches (n = 5 mice for each group). *P < 0.05. H: Number of branching points along 400 μm of arterial branches. Counts were obtained from segments of primary arterial branches between approximately 0.5 and 0.9 mm from the optic nerve head (n = 5 mice for each group). ***P < 0.001. Error bars are standard error of the mean for all graphs.

Neonatal Phd2 CKO mice displayed varying degrees of growth retardation, but they remained viable for at least 3 weeks (viability beyond this stage has not been evaluated). To minimize potential complications originating from growth retardation, we chose to include in experiments only those Phd2 CKO mice that displayed no to mild growth retardation (body mass > 80% of Phd2f/f controls).

We first examined retinal branching morphogenesis at P7. Staining of flat-mounted retinas with Alexa 594-conjugated IB4 revealed increased branching morphogenesis in Phd2 CKO retinas along with apparently larger vascular profiles (Figure 1, C and D). By immunofluorescence staining with anti–smooth muscle cell actin, arterial branches were easily identifiable in both Phd2f/f and Phd2 CKO mice. Interestingly, although arterial branches in Phd2f/f retinas were flanked by capillary-free tissues, numerous microvascular branches were found along arterial branches in Phd2 CKO retinas (Figure 1, E and F).

We quantified branching points per 0.04-mm2 area at midway between the optic nerve head and retinal periphery (excluding areas within 50 μm from either side of arterial branches). As shown in Figure 1G, Phd2 CKO mice had 55 ± 5.1 branches, compared with 40 ± 3.0 in Phd2f/f mice (P < 0.05). Near arterial branches (especially along primary arterial branches), the difference was much more dramatic. Phd2 CKO mice had 21 ± 1.6 branching points per 400 μm of primary arterial branch, whereas the corresponding value in Phd2f/f mice was only 5.8 ± 0.7 (P < 0.001).

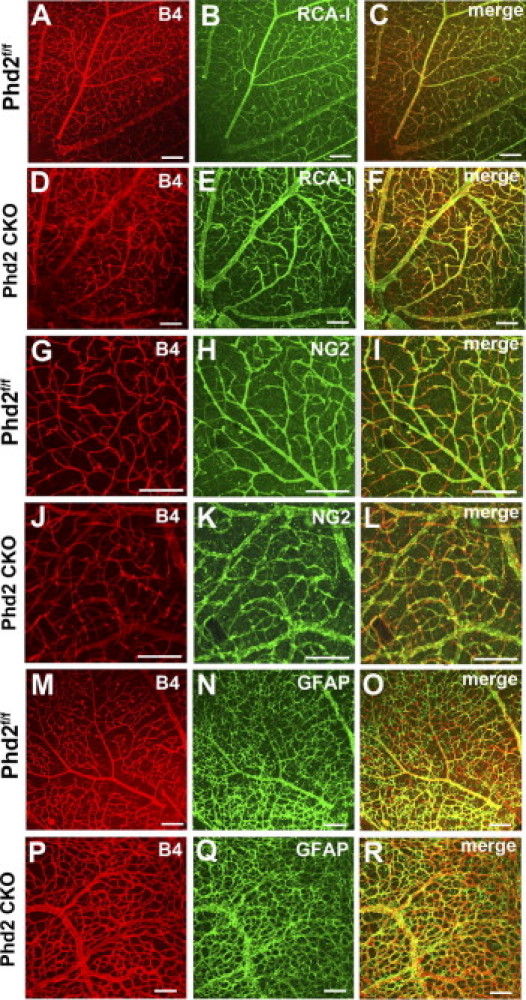

We also assessed several other vascular properties at P17, including perfusion of retinal vascular beds by the main circulatory system, recruitment of pericytes, and alignment with the astrocyte network. To determine whether retinal vascular beds were perfused properly, retinal vascular structures were double stained, first by LV injection of FITC–RCA-I lectin and then with Alexa 594–IB4 after retinas were isolated and flat-mounted. Vascular patterns labeled by these two methods appeared nearly identical in both Phd2f/f and Phd2 CKO mice (Figure 2, A–F), demonstrating that essentially all retinal blood vessels were perfused properly by the main circulation. Pericyte recruitment was examined by double staining of flat-mounted retinas with Alexa 594–IB4 and anti–NG-2. No apparent abnormalities were found (Figure 2, G–L). The alignment between retinal blood vessels and the astrocyte network also appeared normal, as indicated by well-matched vascular and astrocyte distribution patterns resulting from Alexa 594–IB4 and anti-GFAP double staining (Figure 2, M–R).

Figure 2.

Characterization of retinal vascular properties. For all of the following studies, mice were maintained under ambient room air and euthanized at P17. A–F: Analysis of perfusion properties (n = 5 mice per group). Retinal blood vessels were first labeled by FITC–RCA-I lectin (RCA-I) injected into the LV chamber, and subsequently by Alexa 594–IB4 (B4) after RAC-I–labeled retinas were flat-mounted. G–L: recruitment of pericytes (n = 3 mice for each group). Flat-mounted retinas were double-stained by Alexa 594–IB4 and rabbit anti-NG2/goat anti-rabbit IgG–Alexa 488. M–R: Association of blood vessels with astrocytes (n = 3 mice for each group). Flat-mounted retinas were double-stained by Alexa 594–IB4 and rabbit anti-GFAP/goat anti-rabbit IgG–Alexa 488. All images were taken from flat-mounted retinas by laser confocal microscopy. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Based on these analyses, we conclude that PHD2 deficiency led to increased branching morphogenesis and moderate alterations in retinal vascular patterning. However, several other fundamental vascular properties, such as perfusion, vascular maturation, and association with the astrocyte network, were not grossly affected.

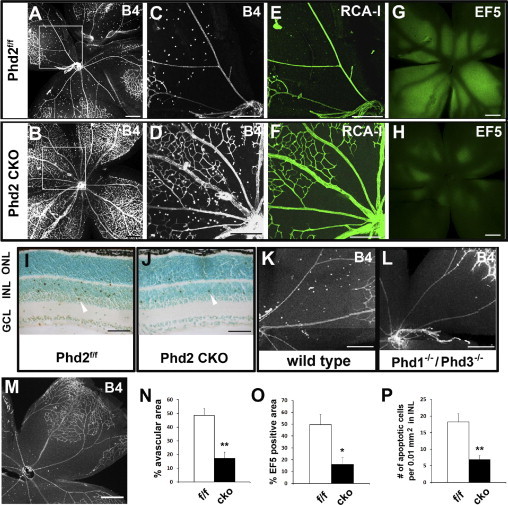

Resistance of PHD2-Deficient Retinal Vasculature to Oxygen-Induced Damages

We examined if PHD2 deficiency enabled retinal microvessels to better tolerate 75% oxygen. For this experiment, mice were analyzed at P12 after being exposed to 75% oxygen for 5 days (P7–P12). Oxygen-treated Phd2f/f mice showed large avascular areas (48.5% ± 5.2% of whole retinal areas) (Figure 3, A, C, and N). By contrast, equally treated Phd2 CKO mice had much smaller avascular areas (17.1% ± 4.7%) (Figure 3, B, D, and N) (P < 0.01). When tamoxifen-treated Phd2+/+/Rosa26CreERT2/+ mice were exposed to 75% oxygen, massive loss of retinal microvessels also occurred (Figure 3M). Thus, resistance of retinal microvessels to oxygen treatment was indeed dependent on PHD2 deficiency.

Figure 3.

Resistance of Phd2 CKO retinas to oxygen-induced damage. Mice in these studies were exposed to 75% oxygen for 5 days between P7 and P12. A–D: Staining of flat-mounted retinas with Alexa 594–IB4 (6 mice per group) at P12. C and D: Expanded images from boxed areas in A and B. E and F: Retinal blood vessels were stained by injection of FITC–RCA-I–lectin into the LV chamber of oxygen-exposed mice (3 mice per group). G and H: Labeling by hypoxia probe EF5 (3 mice per group). EF5 was injected intraperitoneally into oxygen-treated mice, and retinas were dissected after perfusion with saline. Hypoxic tissues were detected by immunofluorescence staining of flat-mounted retinas with Cy3–anti-EF5. I and J: Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling staining of retinal cross-sections (4 mice per group). After exiting the oxygen chamber, mice were left under room air for 6 hours before being euthanized for retina isolation. Arrowheads point to examples of apoptotic cells. K and L: Alexa 594–IB4–stained retinas from wild-type and Phd1−/−/Phd3−/− mice (3 mice per group). M: Alexa 594–IB4–stained retinas from Phd2+/+/Rosa26+/CreERT2 mice (3 mice per group). N: Quantification of avascular retinal tissues in oxygen-treated mice, presented as percentages of whole retinal areas (n = 6 for each group; P < 0.01). O: EF5-labeled (ie, strongly hypoxic) retinal tissues as percentages of whole retinal areas (n = 3 for each group; P < 0.05). P: Number of apoptotic cells per 0.01-mm2 area in the inner nuclear layer (n = 4 for each group; P < 0.01). Scale bars: 300 μm (A–H and K–M); 50 μm (I and J). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Error bars are standard error of the mean.

Next, we examined perfusion properties of retinal vascular beds in P12 mice treated with oxygen as in the earlier-described experiment. To label retinal blood vessels that were perfused properly by the main circulation, FITC–RCA-I lectin was injected into the LV chamber of Phd2f/f and Phd2 CKO mice after oxygen treatment. In central retinal tissues of Phd2f/f mice, FITC–RCA-I lectin–positive microvessels scarcely were found (Figure 3E). However, the corresponding region in Phd2 CKO mice contained numerous microvessels strongly stained by FITC–RCA-I lectin (Figure 3F). Thus, after 5 days of exposure to hyperoxia, loss of perfusion was much less severe in Phd2 CKO retinal tissues.

The earlier-described study was substantiated further by labeling hypoxic tissues with the hypoxia probe EF5. In brief, EF5 was injected intraperitoneally into oxygen-treated mice after they were returned to ambient room air (P12), and retinas from these mice were examined by anti-EF5 immunofluorescence staining. This experiment revealed that approximately 49.7% ± 8.7% of total retinal areas were EF5 positive in Phd2f/f mice, whereas only 16% ± 5.8% of total retinal areas were EF5-positive in Phd2 CKO mice (P < 0.01; Figure 3, G, H, and O). Thus, when oxygen-treated mice were returned to ambient room air, retinal tissue hypoxia was much less severe in Phd2 CKO mice.

To further investigate if PHD2 deficiency protected retinal tissues from oxygen-induced damages, we performed apoptosis assay. Briefly, mice were exposed to 75% oxygen between P7 and P12, and then returned to ambient room air for 6 hours. Retinal histological sections from these mice were analyzed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling staining. Because most signals were located within the inner nuclear layer, we focused our analysis on this layer of retinal tissue. In Phd2f/f retinas, 18.3 ± 2.5 apoptotic cells were counted per 0.01-mm2 area in the inner nuclear layer. In Phd2 CKO retinas, only 6.8 ± 1.3 apoptotic cells were present per equivalent area (P < 0.01; Figure 3, I, J, and P). These data confirmed that retinal tissues in Phd2 CKO mice were less sensitive to oxygen-induced damages.

In sharp contrast to Phd2 knockout, Phd1−/−/Phd3−/− double mutation was not protective. Oxygen treatment of Phd1−/−/Phd3−/− mice from P7 to P12 led to extensive microvascular losses in central retinal tissues, a finding that was indistinguishable from wild-type controls (Figure 3, K and L). Thus, PHD2 is a major prolyl hydroxylase isoform to mediate oxygen-induced microvascular disintegration in retinal tissues.

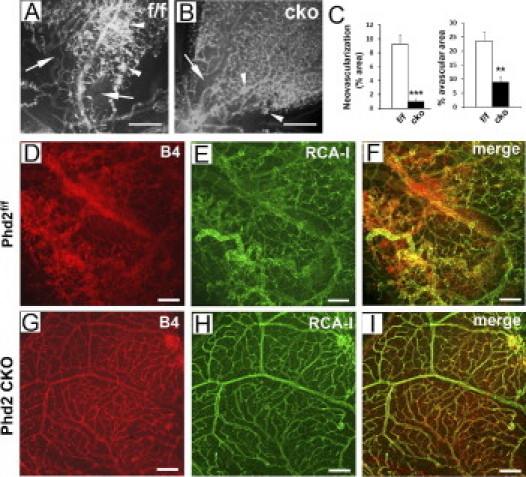

Diminished Retinal Tissue Ischemia and Neoangiogenesis in Phd2 CKO Mice during Phase II of the OIR Model

We also examined retinal vascular properties using the full OIR model. In each of the experiments described in this section, mice were examined at P17, after sequential treatments of 75% oxygen from P7 to P12 and ambient room air from P12 to P17. In Phd2f/f mice, extensive neoangiogenesis was observed (Figure 4A, arrowheads). By contrast, neoangiogenesis was minimal in equally treated Phd2 CKO mice (Figure 4B, arrowheads). On average, neoangiogenesis was present in 9.5% ± 1.3% of whole retinal areas in Phd2f/f mice, whereas the corresponding number for Phd2 CKO mice was only 0.96% ± 0.43% (P < 0.001; Figure 4C, left). Although Phd2 CKO retinas showed very little neoangiogenesis, they were more fully occupied by normal-looking vascular structures than Phd2f/f controls (Figure 4, A and B). In Phd2f/f mice, 23.5% ± 3.3% of entire retinal areas were avascular, whereas in Phd2 CKO mice only 8.8% ± 2.1% of retinal areas were avascular (P < 0.01; Figure 4C, right).

Figure 4.

Lack of significant OIR in Phd2 CKO mice. All mice were analyzed at P17, after being sequentially exposed to 75% oxygen (P7–P12) and ambient room air (P12–P17). A and B: Alexa 594–IB4–stained retinas. Arrowheads indicate neovascular areas; arrows indicate avascular areas. C: Percentage of retinal areas that were neovascular (left) or avascular (right) (n = 4 mice per group). ***P < 0.001 for neoangiogenesis; **P < 0.01 for avascular areas. D–I: Analysis of retinal perfusion properties (n = 3 mice per group). Retinas were double-stained, first by injecting FITC–RCA-I lectin into the LV chamber (E and H) and then by Alexa 594–IB4 staining of flat-mounted retinas (D and G). Vascular patterns labeled by the two methods matched poorly for Phd2f/f retinas (F) but superimposed nearly perfectly for Phd2 CKO retinas (I). Scale bars: 200 μm (A and B); 100 μm (D–I).

To evaluate perfusion properties after sequential oxygen and room air treatments, we examined retinal vascular patterns at P17 by double labeling with FITC–RCA-I lectin (injected into the LV chamber) and Alexa 594–IB4 (flat-mount staining). In Phd2f/f retinas, large patches of irregularly shaped structures were found that were positive for Alexa 594–IB4 but negative for FITC–RCA-I lectin (Figure 4, D–F). This finding indicated that in phase II, poorly organized vascular structures were formed in Phd2f/f retinas, which were not connected to the systemic circulation. By contrast, retinas from Phd2 CKO mice were equally labeled by both methods, resulting in nearly perfect superimposition of FITC–RCA-I lectin and Alexa 594–IB4–stained patterns (Figure 4, G–I). Therefore, we conclude that in the mouse OIR model, PHD2 deficiency helped preserve the connectivity of the retinal vascular network to the systemic vascular system.

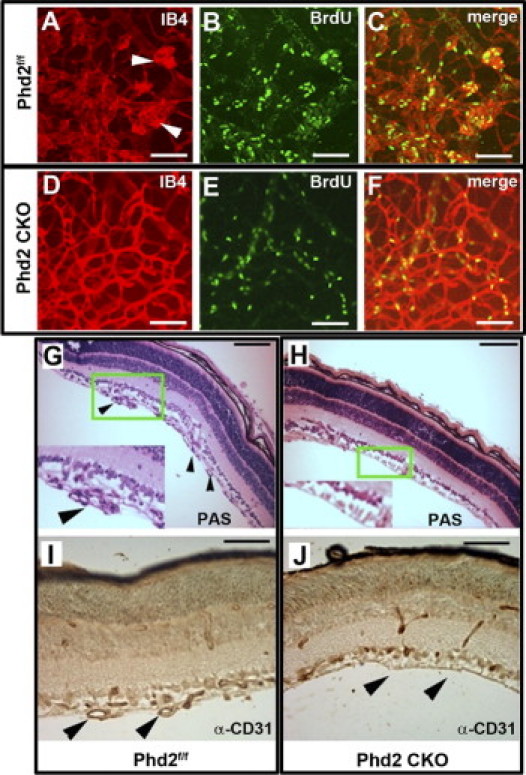

Retinal neoangiogenesis typically is associated with increased endothelial cell proliferation. Thus, we double-labeled retinas with BrdU and Alexa 594–IB4 at the end of phase II (P17). As shown in Figure 5, A–F, the majority of BrdU-labeled cells were superimposed with vascular tufts. Furthermore, Phd2 CKO mice had significantly fewer BrdU-positive cells (27.3 ± 5.0/0.04 mm2 for Phd2f/f mice; 10.7 ± 2.3/0.04 mm2 for Phd2 CKO mice; P < 0.05). In addition to the earlier-described double-labeling experiment, we also examined the formation of vascular tufts by periodic acid-Schiff staining of histological sections. Vascular tufts were abundantly present in Phd2 CKO retinas but were difficult to find in Phd2f/f controls (Figure 5, G and H). Similar results were obtained by anti-CD31 immunohistochemical staining (Figure 5, I and J). These findings confirmed that PHD2 deficiency prevented proliferative retinopathy in the mouse OIR model.

Figure 5.

Analyses of vascular proliferation and tuft formation. Mice were analyzed at P17 after being exposed to 75% oxygen for 5 days between P7 and P12, followed by ambient room air between P12 and P17. A–F: Comparison of distribution patterns between vascular tufts and proliferative (BrdU-positive) cells (n = 3 mice per group). Vascular structures including tufts were stained by Alexa 594–IB4 (A and D); proliferative cells were labeled by BrdU (bright green signals in B and E). Arrowheads in A point to vascular tufts. C and F: Merged images. G and H: Periodic acid-Schiff staining of retinal cross-sections. Three mice were used for each genotype. Insets are enlarged from areas marked by green rectangles. Arrowheads in G indicate vascular tufts. I and J: Anti-CD31 immunohistochemical staining of retinal sections. Arrowheads in I point to vascular tufts; arrowheads in J indicate lack of vascular tufts in the inner retinal surface of Phd2 CKO mice. Three mice were used for each genotype. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Molecular Changes in PHD2-Deficient Retinas

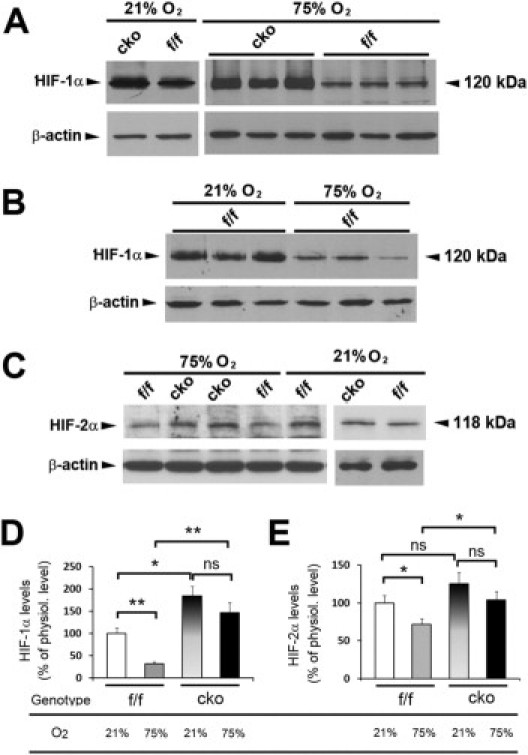

To determine how oxygen affected the abundance of HIF-α proteins, we performed Western blotting assays. Briefly, mice were either exposed to 75% oxygen for 2 days from P7 to P9 (75% O2) or remained untreated (21% O2). At P9, oxygen-treated or untreated mice were euthanized, and nuclear extracts were prepared from retinas. Unless otherwise specified, HIF-α levels are presented as percentages relative to values in untreated Phd2f/f mice, with the latter being arbitrarily set at 100%. In Phd2 CKO mice without oxygen treatment, HIF-1α levels were 164% ± 16.2% (P < 0.05) (Figure 6, A and D). After oxygen treatment, HIF-1α levels remained high in Phd2 CKO retinas (137% ± 12.4%). The difference between oxygen-treated and untreated Phd2 CKO mice was statistically insignificant (P = 0.26). By contrast, in oxygen-treated Phd2f/f mice, retinal HIF-1α protein levels dropped to 32% ± 5.9% (P < 0.01) (Figure 6, B and D). Thus, retinal HIF-1α levels in oxygen-treated Phd2 CKO mice was 4.3-fold ± 0.38-fold relative to equally treated Phd2f/f mice (P < 0.01). These data are consistent with the possibility that HIF-1α in Phd2 CKO retinas may resist oxygen-induced degradation. Some examples comparing retinal HIF-1α levels in oxygen-treated Phd2 CKO and Phd2f/f mice are shown in Figure 6A (right panel).

Figure 6.

Western blotting analyses of HIF-1α and HIF-2α levels. Mice were analyzed at P9, either housed continuously under room air (21% O2) or with a 2-day treatment of 75% O2 between P7 and P9 (75% O2). Retinal nuclear extracts were used for all experiments. A: Comparison of HIF-1α abundance between Phd2f/f (f/f) and Phd2 CKO (cko) mice. B: Comparison of HIF-1α abundance in Phd2f/f mice with and without a 2-day exposure to 75% O2 between P7 and P9. C: Anti–HIF-2α Western blots. D and E: Quantification of HIF-1α (D) and HIF-2α (E) protein levels. All band intensities were normalized against β-actin. Graphs summarize data from the following number of mice tested for each group: i) anti–HIF-1α blotting: n = 8 for Phd2f/f (21% O2); n = 3 for Phd2 CKO (21% O2); n = 8 for Phd2f/f (75% O2); n = 3 for Phd2 CKO (75% O2); ii) anti–HIF-2α blotting: n = 8 for Phd2f/f (21% O2); n = 8 for Phd2f/f (75% O2); n = 6 for Phd2 CKO (21% O2); n = 6 for Phd2 CKO (75% O2). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. ns, not significant (P > 0.05). Error bars are standard error of the mean.

HIF-2α displayed qualitatively similar changes in response to PHD2 deficiency and/or oxygen treatment. Quantitatively, however, the changes were much less robust (Figure 6, C and E). Without exposure to 75% oxygen, HIF-2α levels in Phd2 CKO mice were 125% ± 15% of Phd2f/f controls, but this apparent increase was statistically insignificant (P = 0.195). After hyperoxia treatment, HIF-2α protein levels in Phd2 CKO retinas trended lower to 103% ± 11.3%, but the reduction was insignificant (P = 0.276). In oxygen-treated Phd2f/f mice, HIF-2α protein levels were reduced to 71.9% ± 7.4% (P < 0.05). Importantly, when oxygen-treated Phd2 CKO and Phd2f/f mice were compared, it was clear that Phd2 CKO mice had significantly higher levels of retinal HIF-2α (144% ± 15.7% relative to oxygen-treated Phd2f/f mice; P < 0.05).

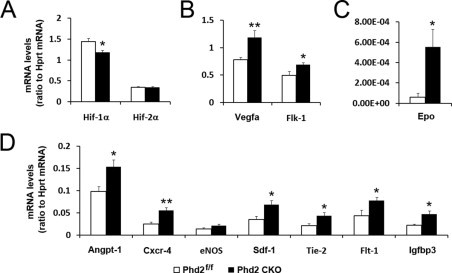

We also performed qPCR to determine the expression levels of various genes whose protein products are involved in angiogenesis and/or vascular integrity. Some of these genes, such as Vegfa,8,34 Sdf-1,10,35 and Epo,12,13,36 are HIF targets. For this study, mice were exposed to 75% oxygen for 16 hours between P7 and P8, and total retinal RNA samples were isolated for qPCR analyses. This particular combination of age and oxygen treatment was chosen for the study based on the assumption that molecular changes occurring at the early phase of oxygen treatment are more likely to reflect responses to oxygen exposure, whereas those occurring later into oxygen treatment may be complicated by additional events, such as tissue damage and poor perfusion.

As expected, Hif-1α and Hif-2α mRNA levels were not increased in PHD2-deficient retinas (Figure 7A). However, Hif-1α mRNA level was reduced unexpectedly, although the reduction was modest. The precise reason for this finding currently is unknown. Importantly, most of the tested mRNAs, including Vegfa, Flk-1 (Figure 7B), Epo (Figure 7C), Sdf-1, Cxcr-4, Angpt-1, Tie-2, Flt-1, and Igfbp-3 (Figure 7D), were more abundant in PHD2-deficient retinal tissues.

Figure 7.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses for mRNA abundance. Total retinal RNA samples were isolated from mice at P8 after a prior exposure to 75% oxygen for 16 hours between P7 and P8. Data are presented as ratios between signal intensities of specific mRNAs and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) (n = 6 for each group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Error bars are standard error of the mean

Discussion

A major conclusion from this study is that oxygen-induced retinal microvascular obliteration is mediated mostly by PHD2. Improved vascular integrity in PHD2-deficient retinas was associated closely with increased HIF-α stability, especially HIF-1α. When mice expressing normal levels of PHD2 were exposed to 75% O2, nuclear HIF-1α abundance was reduced dramatically in retinal tissues, accompanied by massive losses of retinal microvessels. However, in oxygen-treated Phd2 CKO neonatal mice, high levels of retinal HIF-1α persisted, along with well-preserved retinal vascular networks. Given that HIF-α proteins are crucial for the expression of important endothelial cell growth and survival factors, we suggest that in Phd2 CKO retinas, increased stability of HIF-α (more notably HIF-1α) at least partially explains why PHD2-deficient retinal microvessels are more resistant to oxygen treatment. On the other hand, data from this study do not rule out possible involvement of other mechanisms as well.

Our observation that retinal HIF-α is greatly reduced in oxygen-treated Phd2f/f mice contradicts a recent report that concluded that retinal HIF-α proteins in wild-type mice were not affected by hyperoxia.37 Although the exact reasons for such a discrepancy are unknown, it may be informative to note that our initial findings also indicated that retinal HIF-α levels were not reduced in oxygen-treated Phd2f/f mice. However, the following two modifications, both of which are described in detail in the Materials and Methods section, allowed us to more accurately determine retinal nuclear HIF-α levels in oxygen-treated mice. First, we suspected that between the removal of mice from the oxygen chamber and homogenization of isolated retinas, de novo HIF-α synthesis might occur in retinal cells, which might remain viable for some time. Thus, we made various efforts to minimize possible do novo synthesis and accumulation during this time period, including euthanizing mice as swiftly as possible after exiting the oxygen chamber, maintaining euthanized mice deep in ice, dissecting retinas in PBS prechilled in ice, and performing homogenization in ice-cold buffers; second, because transcriptionally active HIF-α proteins are localized in the nucleus, we prepared nuclear extracts instead of total retinal lysates for Western blotting analyses.

Because Rosa26CreERT2 is broadly expressed, we cannot exclude the possibility that HIF-α in nonretinal tissues also might exert their effects on retinal development and vascular stability, possibly mediated by circulating angiogenic factors.38 On the other hand, the accumulation of retinal HIF-α in Phd2 CKO mice correlated with up-regulated retinal expression of HIF target genes known to be important for angiogenesis and vascular stability. Thus, it is very likely that retinal PHD2 may directly mediate retinal vascular development and oxygen-dependent microvascular obliteration. This viewpoint agrees well with previous findings indicating that reduced retinal expression of angiogenic factors such as VEGF-A and IGFBP-3 contributed to oxygen-induced microvascular losses.39,40

Protection of retinal microvessels was incomplete in Phd2 CKO mice, which showed some microvascular losses after being exposed to 75% oxygen. Although this outcome might reflect the contribution of other mechanisms, such as oxidative stress,41 it can be explained more simply by the presence of residual PHD2 proteins. In addition, it also is possible that PHD1 and/or PHD3 might compensate for PHD2 in Phd2 CKO mice, although in the presence of a normal amount of PHD2 these other PHD isoforms are not noticeably involved in oxygen-induced vascular damages. In this regard, it is interesting to note that Phd3 mRNA is up-regulated in PHD2-deficient retinas.

In the mouse OIR model, superior structural integrity in Phd2 CKO mice also extended to offer improved preservation of vascular functions. In Phd2f/f mice, numerous vascular tufts were formed in phase II as a result of overproliferation of vascular endothelial cells. The presence of numerous vascular tufts is indicative of nonfunctional and mislocated microvessels. Indeed, retinal vascular structures were poorly perfused when Phd2f/f mice were subject to OIR treatment. In Phd2 CKO mice, however, vascular tufts were rarely found, and retinal microvessels displayed normal perfusion properties.

It is well known that HIF-α accumulation in ischemic retinal tissues contributes to neoangiogenesis and formation of vascular tufts.42,43 In Phd2 CKO mice, HIF-α proteins, especially HIF-1α, are present at increased levels. Nonetheless, other than increased branching morphogenesis, which generates extra but mostly normal blood vessels, there is little neoangiogenesis to form vascular tufts. Although precise answers are not yet available to explain this phenomenon, we believe that several reasons may partially account for the lack of neoangiogenesis in Phd2 CKO retinas. First, both HIF-1α and HIF-2α accumulate to high levels during retinal ischemia in the mouse OIR model,37 and functional studies indicated that HIF-2α may play a crucial role in retinal neoangiogenesis.42,43 In Phd2 CKO retinas, HIF-1α accumulates to high levels, whereas HIF-2α accumulation is modest. Second, the timing of HIF-α accumulation is different. In Phd2 CKO mice, high levels of HIF-1α are already present early during retinal vascular development, whereas HIF-α accumulation in the OIR model bursts abruptly after mice are returned to room air.37 Third, hypoxia in ischemic retinal tissues may in theory inhibit hydroxylase activities of all PHD isoforms, whereas in the present study only PHD2 is deficient. Finally, in phase II of the OIR model, retinal tissue hypoxia in Phd2 CKO mice is minimal compared with equally treated Phd2f/f mice. It is highly likely that lack of severe ischemia may be a major reason for the lack of oxygen-induced retinopathy (neoangiogenesis) in Phd2 CKO mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that PHD2 deficiency protects Phd2 CKO mice from oxygen-induced retinopathy. In phase I of the OIR model, Phd2 CKO mice show significantly improved microvascular integrity, and in phase II these mice are almost free of neoangiogenesis. These findings raise the hope that it might be possible to protect human beings from OIR by specifically targeting PHD2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin Claffey, Nancy Ryan, Athanasia Skoura, and Vivienne Ho for technical assistance, Alex Joyner for Rosa26CreERT2/+ mice, and Cameron Koch for EF5 and anti-EF5.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R01EY019721) and the March of Dimes (grant FY07-273).

References

- 1.Chen M., Citil A., McCabe F., Leicht K.M., Fiascone J., Dammann C.E., Dammann O. Infection: Oxygen, and immaturity: interacting risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity. Neonatology. 2010;99:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000312821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith L.E. Pathogenesis of retinopathy of prematurity. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:469–473. doi: 10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidary G., Vanderveen D., Smith L.E. Retinopathy of prematurity: current concepts in molecular pathogenesis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24:77–81. doi: 10.1080/08820530902800314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith L.E., Wesolowski E., McLellan A., Kostyk S.K., D'Amato R., Sullivan R., D'Amore P.A. Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arjamaa O., Nikinmaa M. Oxygen-dependent diseases in the retina: role of hypoxia-inducible factors. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang B.H., Rue E., Wang G.L., Roe R., Semenza G.L. Dimerization: DNA binding, and transactivation properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17771–17778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ema M., Taya S., Yokotani N., Sogawa K., Matsuda Y., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsythe J.A., Jiang B.H., Iyer N.V., Agani F., Leung S.W., Koos R.D., Semenza G.L. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saint-Geniez M., Kurihara T., Sekiyama E., Maldonado A.E., D’Amore P.A. An essential role for RPE-derived soluble VEGF in the maintenance of the choriocapillaris. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18751–18756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly B.D., Hackett S.F., Hirota K., Oshima Y., Cai Z., Berg-Dixon S., Rowan A., Yan Z., Campochiaro P.A., Semenza G.L. Cell type-specific regulation of angiogenic growth factor gene expression and induction of angiogenesis in nonischemic tissue by a constitutively active form of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Circ Res. 2003;93:1074–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000102937.50486.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceradini D.J., Kulkarni A.R., Callaghan M.J., Tepper O.M., Bastidas N., Kleinman M.E., Capla J.M., Galiano R.D., Levine J.P., Gurtner G.C. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semenza G.L., Wang G.L. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5447–5454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kertesz N., Wu J., Chen T.H., Sucov H.M., Wu H. The role of erythropoietin in regulating angiogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;276:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein A.C., Gleadle J.M., McNeill L.A., Hewitson K.S., O'Rourke J., Mole D.R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M.I., Dhanda A., Tian Y.M., Masson N., Hamilton D.L., Jaakkola P., Barstead R., Hodgkin J., Maxwell P.H., Pugh C.W., Schofield C.J., Ratcliffe P.J. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruick R.K., McKnight S.L. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivan M., Haberberger T., Gervasi D.C., Michelson K.S., Gunzler V., Kondo K., Yang H., Sorokina I., Conaway R.C., Conaway J.W., Kaelin W.G., Jr Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13459–13464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192342099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell P.H., Wiesener M.S., Chang G.W., Clifford S.C., Vaux E.C., Cockman M.E., Wykoff C.C., Pugh C.W., Maher E.R., Ratcliffe P.J. The tumour suppressor protein PVHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutter C.H., Laughner E., Semenza G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha protein expression is controlled by oxygen-regulated ubiquitination that is disrupted by deletions and missense mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4748–4753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080072497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallio P.J., Wilson W.J., O'Brien S., Makino Y., Poellinger L. Regulation of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6519–6525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semenza G.L. Involvement of oxygen-sensing pathways in physiologic and pathologic erythropoiesis. Blood. 2009;114:2015–2019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-189985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong G.H. Regulation of angiogenesis by oxygen sensing mechanisms. J Mol Med. 2009;87:549–560. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0458-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myllyharju J. HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases and their potential as drug targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:3878–3885. doi: 10.2174/138161209789649457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fandrey J., Gassmann M. Oxygen sensing and the activation of the hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1)–invited article. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;648:197–206. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2259-2_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uno K., Prow T.W., Bhutto I.A., Yerrapureddy A., McLeod D.S., Yamamoto M., Reddy S.P., Lutty G.A. Role of Nrf2 in retinal vascular development and the vaso-obliterative phase of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byfield G., Budd S., Hartnett M.E. The role of supplemental oxygen and JAK/STAT signaling in intravitreous neoangiogenesis in a ROP rat model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3360–3365. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardy P., Dumont I., Bhattacharya M., Hou X., Lachapelle P., Varma D.R., Chemtob S. Oxidants, nitric oxide and prostanoids in the developing ocular vasculature: a basis for ischemic retinopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:489–509. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda K., Cowan A., Fong G.H. Essential role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis of the adult vascular system. Circulation. 2007;116:774–781. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda K., Ho V.C., Takeda H., Duan L.J., Nagy A., Fong G.H. Placental but not heart defects are associated with elevated hypoxia-inducible factor alpha levels in mice lacking prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8336–8346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00425-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connor K.M., Krah N.M., Dennison R.J., Aderman C.M., Chen J., Guerin K.I., Sapieha P., Stahl A., Willett K.L., Smith L.E. Quantification of oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse: a model of vessel loss, vessel regrowth and pathological angiogenesis. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minamishima Y.A., Moslehi J., Padera R.F., Bronson R.T., Liao R., Kaelin W.G., Jr A feedback loop involving the Phd3 prolyl hydroxylase tunes the mammalian hypoxic response in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5729–5741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00331-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aprelikova O., Chandramouli G.V., Wood M., Vasselli J.R., Riss J., Maranchie J.K., Linehan W.M., Barrett J.C. Regulation of HIF prolyl hydroxylases by hypoxia-inducible factors. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:491–501. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marxsen J.H., Stengel P., Doege K., Heikkinen P., Jokilehto T., Wagner T., Jelkmann W., Jaakkola P., Metzen E. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes its degradation by induction of HIF-alpha-prolyl-4-hydroxylases. Biochem J. 2004;381:761–767. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stiehl D.P., Wirthner R., Koditz J., Spielmann P., Camenisch G., Wenger R.H. Increased prolyl 4-hydroxylase domain proteins compensate for decreased oxygen levels: Evidence for an autoregulatory oxygen-sensing system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23482–23491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikeda E., Achen M.G., Breier G., Risau W. Hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation and increased mRNA stability of vascular endothelial growth factor in C6 glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19761–19766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zagzag D., Krishnamachary B., Yee H., Okuyama H., Chiriboga L., Ali M.A., Melamed J., Semenza G.L. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6178–6188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruber M., Hu C.J., Johnson R.S., Brown E.J., Keith B., Simon M.C. Acute postnatal ablation of Hif-2alpha results in anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2301–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608382104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mowat F.M., Luhmann U.F., Smith A.J., Lange C., Duran Y., Harten S., Shukla D., Maxwell P.H., Ali R.R., Bainbridge J.W. HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha are differentially activated in distinct cell populations in retinal ischaemia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sears J.E., Hoppe G., Ebrahem Q., Anand-Apte B. Prolyl hydroxylase inhibition during hyperoxia prevents oxygen-induced retinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19898–19903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805817105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lofqvist C., Chen J., Connor K.M., Smith A.C., Aderman C.M., Liu N., Pintar J.E., Ludwig T., Hellstrom A., Smith L.E. IGFBP3 suppresses retinopathy through suppression of oxygen-induced vessel loss and promotion of vascular regrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10589–10594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang K.H., Chan-Ling T., McFarland E.L., Afzal A., Pan H., Baxter L.C., Shaw L.C., Caballero S., Sengupta N., Li Calzi S., Sullivan S.M., Grant M.B. IGF binding protein-3 regulates hematopoietic stem cell and endothelial precursor cell function during vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10595–10600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702072104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kojima H., Otani A., Oishi A., Makiyama Y., Nakagawa S., Yoshimura N. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor attenuates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells and exhibits functional and morphological protective effect in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Blood. 2010;117:1091–1100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morita M., Ohneda O., Yamashita T., Takahashi S., Suzuki N., Nakajima O., Kawauchi S., Ema M., Shibahara S., Udono T., Tomita K., Tamai M., Sogawa K., Yamamoto M., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. HLF/HIF-2alpha is a key factor in retinopathy of prematurity in association with erythropoietin. EMBO J. 2003;22:1134–1146. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dioum E.M., Clarke S.L., Ding K., Repa J.J., Garcia J.A. HIF-2alpha-haploinsufficient mice have blunted retinal neoangiogenesis due to impaired expression of a proangiogenic gene battery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2714–2720. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]