Abstract

The host immune response directed against Helicobacter pylori is ineffective in eliminating the organism and strains harboring the cag pathogenicity island augment disease risk. Because eosinophils are a prominent component of H. pylori–induced gastritis, we investigated microbial and host mechanisms through which H. pylori regulates eosinophil migration. Our results indicate that H. pylori increases production of the chemokines CCL2, CCL5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by gastric epithelial cells and that these molecules induce eosinophil migration. These events are mediated by the cag pathogenicity island and by mitogen-activated protein kinases, suggesting that eosinophil migration orchestrated by H. pylori is regulated by a virulence-related locus.

Helicobacter pylori is the strongest known risk factor for peptic ulceration and gastric adenocarcinoma.1 Virtually all infected individuals develop co-existing gastric inflammation that persists for decades; however, only a fraction of colonized persons ever develop disease. Host genetic diversity and strain-specific virulence factors contribute to enhanced disease risk, and one such virulence locus is the cag pathogenicity island.1

Several cag genes encode components of a type IV secretion system that exports bacterial proteins into host cells. One such protein, CagL, functions as a bacterial adhesin that binds α5 β1 integrin receptors, triggering the delivery of the terminal gene product of the cag island, CagA, into host cells.2 After its injection into epithelial cells, CagA undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation, which leads to morphological changes in host cells that are reminiscent of unrestrained stimulation by growth factors.

In addition to CagA, the cag secretion system delivers components of H. pylori peptidoglycan into host cells, where they are recognized by nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 1 (Nod1), an intracytoplasmic pattern-recognition molecule. The sensing of H. pylori peptidoglycan by Nod1 activates nuclear factor κB and type I interferon.3–5 Another consequence of cag island–mediated H. pylori–epithelial cell contact is activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), such as p38, extracellular signal–related kinase (ERK) 1/2, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK).4,6

An independent H. pylori locus associated with gastric cancer is vacA, which encodes a secreted bacterial cytotoxin VacA.1 In vitro, VacA induces the formation of intracellular vacuoles, promotes apoptosis, and suppresses T-cell activation, which may contribute to the longevity of H. pylori colonization.

Chronic active gastritis induced by H. pylori is characterized by lymphocyte, plasma cell, macrophage, and eosinophil infiltration.7 Eosinophils are bone marrow–derived granulocytes that contain microbicidal proteins, such as major basic protein, eosinophil cationic protein, and eosinophil peroxidase, and eosinophil degranulation plays a pathogenic role in multiple diseases. Furthermore, enhanced eosinophil levels are present in many tumors, including those that arise within the gastrointestinal tract.8

Eosinophil migration is mediated by chemokines such as CCL2 (monocyte chemotactic protein 1), CCL3 (macrophage inflammatory protein 1), CCL5 (regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted), CCL11 (eotaxin 1), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), but the mechanism through which H. pylori recruits eosinophils to the gastric mucosa is unknown. Interaction of H. pylori with gastric epithelial cells results in the production of chemokines,1 which may potentially regulate the recruitment of eosinophils. Since H. pylori intimately interacts with gastric epithelial cells throughout the infection, we investigated whether chemokine secretion from H. pylori–infected gastric epithelial cells mediates eosinophil migration.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents

MKN28 human gastric epithelial cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO/BRL, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The p38 inhibitor SB203580 and the JNK1/2/3 inhibitor JNK inhibitor II (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) were used at a final concentration of 10 μmol/L. The MEK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was used at a final concentration of 50 μmol/L. MAPK inhibitors were added to confluent MKN28 cells 1 hour before co-culture with H. pylori. These inhibitors have been previously shown by our laboratory to completely inhibit the corresponding MAPK pathways.9

Bacterial Strains and Co-Culture

The H. pylori cag+ strain 60190 was used for all co-culture experiments. Isogenic cagA−, cagL−, slt− (leading to inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis), and vacA− null mutants were constructed by insertional mutagenesis using aphA (conferring kanamycin resistance) and were selected on Brucella agar with kanamycin (25 μg/mL).9 Heat-killed H. pylori were generated by heating bacteria to 80°C for 10 minutes.

H. pylori was grown in Brucella broth supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum for 16 hours and then co-cultured with MKN28 cells at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Supernatants were collected 24 hours after infection by centrifugation, passed through 0.2-μm syringe filters (Corning, Corning, NY), aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use.

Eosinophil Isolation and Migration Assay

Eosinophils were isolated from peripheral blood of healthy volunteers that were H. pylori seronegative in accordance with the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University. Whole blood was diluted 1:1 with 2 mmol/L EDTA in PBS, layered over Histopaque (d = 1.077; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and centrifuged at 600 × g for 30 minutes. The granulocyte pellet was depleted of erythrocytes by hypotonic lysis, and eosinophils were isolated using a magnetic eosinophil isolation kit with the autoMACS instrument as per the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Purity of eosinophils was analyzed by flow cytometry using an anti-CD16 antibody and determined to be 99% or greater.

Migration assays were performed in 96-well ChemoTx plates (NeuroProbe Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) with a 5-μm pore polycarbonate filter as per the manufacturer's instructions. Co-culture supernatants, medium alone, or recombinant chemokines were added to plate wells, and 1 × 105 eosinophils were added to the top of the filter. Plates were incubated for 105 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2. Filters were then washed with PBS to remove eosinophils, scraped, and centrifuged to remove cells from the underside of the filter. For enumeration of migrated eosinophils, the following protocol was developed for this study. Flow cytometry absolute count standard beads (Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA) were added to each well (30,000 per well), and cells were quantified using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Beads and eosinophils were gated separately, and the stopping gate was set at 10,000 beads. The number of eosinophils collected was enumerated and then multiplied by the dilution factor (df = 3) to determine the total number of migrated eosinophils. A standard curve was generated by adding eosinophils directly to the wells of each plate via twofold serial dilution.

Quantification of Cytokines and Chemokines

Co-culture supernatants were assayed for cytokines and chemokines by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based systems (SearchLight System, Aushon Biotechnology, Woburn, MA; and Millipore, BioPharma, St. Charles, MO), in which captured antibodies were spotted in arrays with microplate wells to allow detection of cytokines simultaneously by chemiluminescence. Levels of CCL2, CCL5, and GM-CSF mRNA in MKN28 cell lysates co-cultured with or without H. pylori were assessed by real-time RT-PCR as previously described.9

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted by comparing mean levels of eosinophil counts and chemokine concentrations by grouping variables using repeated-measures analysis of variance. To estimate the difference between the number of migrated eosinophils cultured alone or in the presence of H. pylori strains, a linear mixed-effects model with a random intercept was used. A linear mixed-effects regression model was used to compare chemokine concentrations under different conditions. All analyses were conducted using the R statistical package, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

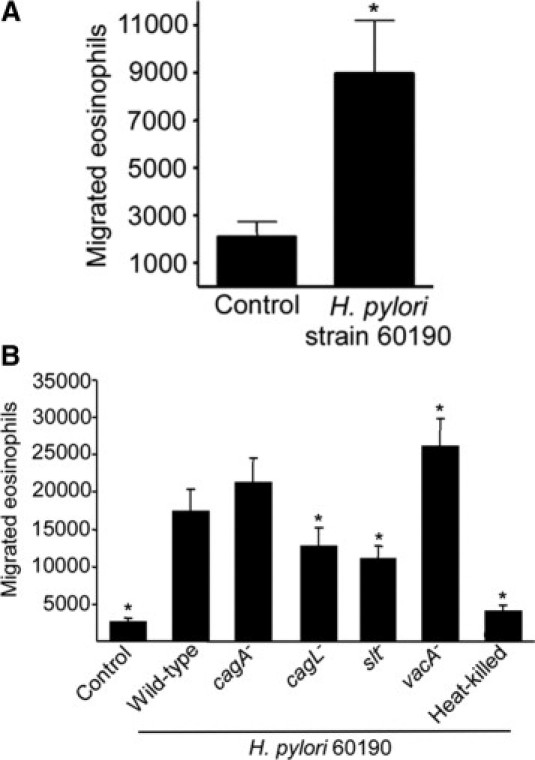

Eosinophils are a prominent component of the inflammatory infiltrate within H. pylori–infected gastric mucosa7; therefore, we determined whether co-culture of H. pylori with gastric epithelial cells could directly induce eosinophil migration. Supernatants from MKN28 cells with medium alone or co-cultured with H. pylori strain 60190 were used in migration assays. Co-culture supernatants from H. pylori–infected MKN28 cells significantly increased eosinophil migration compared with conditioned media from MKN28 cells alone (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Co-culture of H. pylori with gastric epithelial cells induces eosinophil migration and chemokine production. A: Eosinophil migration toward supernatants harvested from MKN28 cells cultured alone or in the presence of wild-type H. pylori strain 60190. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 7 experiments. *P < 0.003 vs control. B: Eosinophil migration toward supernatants harvested from MKN28 cells cultured alone (control) or in the presence of wild-type H. pylori strain 60190, isogenic cagA−, cagL−, slt−, or vacA− mutants, or heat-killed H. pylori. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 5 experiments. *P < 0.05 versus 60190.

Induction of eosinophil migration required live bacteria because heat-killed H. pylori were unable to induce eosinophil migration (Figure 1B). Therefore, we next investigated whether specific H. pylori virulence constituents mediate eosinophil migration by targeting genes within the cag pathogenicity island. MKN28 cells were cultured with medium alone or in the presence of wild-type H. pylori strain 60190 or isogenic cagA−, cagL−, slt−, or vacA− mutants, and supernatants were used in migration assays. The cagA− mutant was no different from the wild-type strain in terms of inducing eosinophil migration (Figure 1B). However, the cagL− mutant induced significantly less migration compared with levels induced by the wild-type strain (Figure 1B), indicating that eosinophil migration was dependent on CagL but not CagA. The slt− mutant, which limits the amount of peptidoglycan available for translocation by the cag secretion system,3 also induced significantly less eosinophil migration than the wild-type strain (Figure 1B). Thus, H. pylori infection of gastric epithelial cells is required for eosinophil migration, and this is dependent on a functional cag secretion system.

In contrast to the cag island mutants, supernatants from MKN28 cells co-cultured with the vacA− mutant induced significantly increased levels of eosinophil migration compared with wild-type H. pylori strain 60190 (Figure 1B).

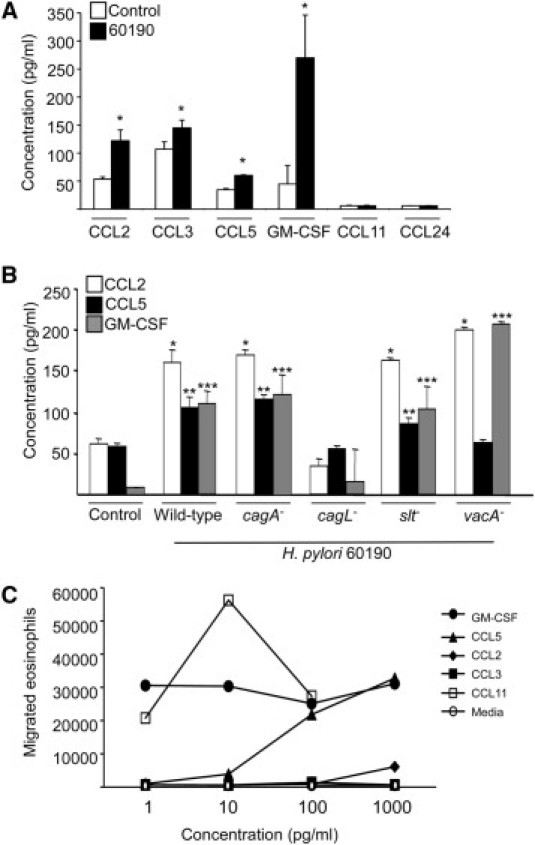

H. pylori induces production of a multitude of proinflammatory cytokines by gastric epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo.1 Having demonstrated that supernatants from H. pylori–infected MKN28 cells induce eosinophil migration, we next assayed for the presence of specific chemokines linked to eosinophil migration to define induced host elements that may mediate eosinophil migration in this context. These included CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CCL7, CCL8, CCL11, CCL13, CCL24, CCL26, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, interleukin-3, interleukin-5, and GM-CSF. Gastric epithelial cell production of only CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, and GM-CSF was significantly increased in the presence of H. pylori strain 60190 compared with medium alone (Figure 2A). Of interest, chemokines that inhibit eosinophil migration, such as CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, were not significantly altered by the presence of H. pylori (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Chemokines induced by H. pylori infection of gastric epithelial cells mediate eosinophil migration. A: Chemokine concentrations in the supernatants of MKN28 cells cultured alone or in the presence of H. pylori strain 60190. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 5 experiments. *P = 0.013, 0.047, 0.0002, and 0.021 for CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, and GM-CSF, respectively, versus uninfected controls. B: Chemokine concentrations in the supernatants of MKN28 cells cultured alone or in the presence of H. pylori wild-type strain 60190 or isogenic cagA−, cagL−, slt−, or vacA− mutants. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 5 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs CCL2 control. **P < 0.05 vs CCL5 control. ***P < 0.05 vs GM-CSF control. C: Eosinophil migration toward media alone or increasing concentrations of the chemokines CCL11 (positive control), GM-CSF, CCL5, CCL2, or CCL3.

Having identified bacterial virulence factors that mediate eosinophil migration (Figure 1B), we next investigated the ability of isogenic mutants that lacked these factors to alter production of secreted cytokines with chemotactic potential (Figure 2B). Similar to the results for eosinophil migration, the cagA− mutant was no different from the wild-type strain in terms of inducing chemokine secretion. In contrast, the cagL− mutant induced significantly less secretion of CCL2, CCL5, and GM-CSF into co-culture supernatants compared with levels induced by the wild-type strain (Figure 2B), consistent with results focused on eosinophil migration (Figure 1B). Of interest, inactivating slt had no discernible effect on chemokine induction compared with levels induced by wild-type H. pylori (Figure 2B). In contrast, for the vacA− mutant that increased eosinophil migration (Figure 1B), levels of CCL2 and GM-CSF were significantly increased, whereas CCL5 levels were significantly decreased by VacA-deficient co-culture supernatants when compared with wild-type H. pylori (Figure 2B).

We next performed functional assays to investigate the ability of individual chemokines induced by H. pylori/MKN28 co-culture to stimulate eosinophil migration. CCL11 was used as a positive control and potently induced eosinophil migration (Figure 2C). CCL2, CCL5, and GM-CSF, but not CCL3, stimulated eosinophil migration in a concentration-dependent manner, with GM-CSF being the most potent attractant (Figure 2C). Thus, three of the four chemokines induced by H. pylori infection of MKN28 cells were able to induce eosinophil migration.

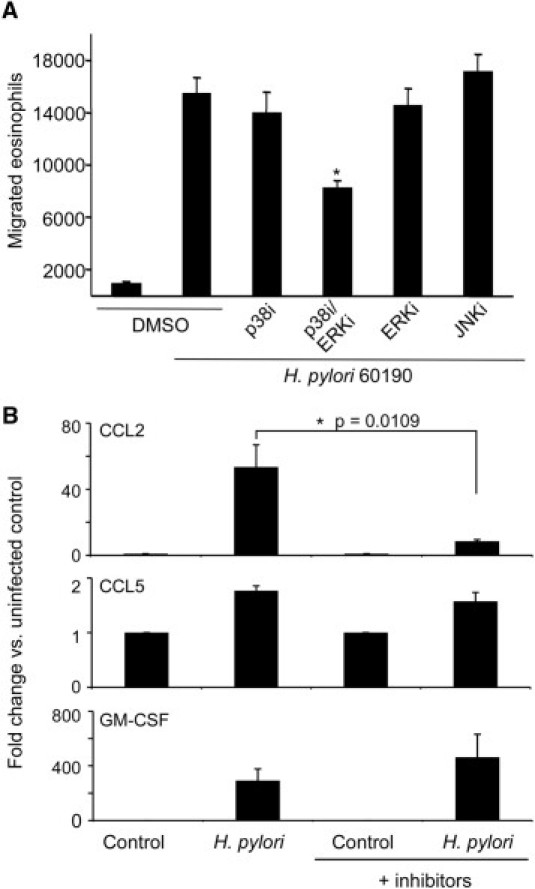

Having demonstrated that H. pylori co-culture with MKN28 cells mediates eosinophil migration, we next investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying these events. H. pylori induces MAPK signal transduction pathways in gastric epithelial cells,6 and these pathways can regulate cytokine secretion. Therefore, to ascertain whether these signaling components mediate eosinophil migration in response to H. pylori, MAPKs were disrupted via pharmacological inhibition, and migration was examined. Inhibition of JNK did not affect eosinophil migration (Figure 3A). Disruption of either p38 or ERK alone partially attenuated eosinophil migration; however, addition of p38 and ERK inhibitors together significantly decreased eosinophil migration (Figure 3A). These results indicate that p38 and ERK cooperate in mediating H. pylori–induced gastric epithelial cell stimulation of eosinophil migration.

Figure 3.

Effect of MAPK inhibition on H. pylori–induced eosinophil migration and gastric epithelial cell chemokine expression. A: Eosinophil migration toward supernatants harvested from MKN28 cells cultured alone or in the presence of wild-type H. pylori strain 60190 with or without SB203580 (p38i), PD98059 (ERKi), or JNK inhibitor II (JNKi). Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 5 experiments. *P < 0.05 versus 60190 in the presence of vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) alone. B: Chemokine expression in cell lysates harvested from MKN28 cells cultured alone or in the presence of H. pylori strain 60190 with or without SB203580 (p38i) and PD98059 (ERKi) as assessed by real-time RT-PCR. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 5 experiments. *P = 0.0109 versus 60190 in the presence of vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) alone.

To define more clearly the mechanism through which MAPK may exert effects on eosinophil migration, p38- and ERK-dependent pathways were disrupted in gastric epithelial cells co-cultured with or without H. pylori via pharmacological inhibition, and expression of CCL2, CCL5, and GM-CSF was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Inhibition of p38 and ERK significantly decreased CCL2, but not CCL5 or GM-CSF, expression compared with H. pylori–infected controls (Figure 3B). These results indicate that p38 and ERK likely alter eosinophil migration by different mechanisms, which is chemokine dependent.

Discussion

The gastrointestinal immune system is exquisitely poised to detect and respond to bacteria residing at mucosal surfaces. However, pathogens have developed multiple strategies to subvert the mucosal immune response; consequently, microbes contribute to the development of more than 1 million cases of cancer per year. H. pylori is the strongest identified risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, and persistence of this pathogen is mediated by an ineffective adaptive immune response that is characterized by insufficient TH1 and TH17 responses and inappropriate regulatory T-cell activation. Eosinophils can produce cytokines that influence both TH2 and TH1 responses and are well-positioned effectors to modify the T-cell response to H. pylori; thus, eosinophil infiltration likely contributes to the ability of H. pylori to infect its human host for decades.

Our data now implicate the cag pathogenicity island but not CagA per se as a necessary factor for recruitment of eosinophils in vitro, and these findings are consistent with studies using gastric tissue specimens. Previous reports have demonstrated that there is no correlation between eosinophil density in the gastric mucosa and CagA antibody titer in the same patients.10 Of interest, we also found that loss of VacA increased eosinophil migration in vitro, and these results are concordant with recent data demonstrating that VacA may counteract effects of the cag island in host cells.11,12

The chronic inflammatory response that develops in response to H. pylori is a critical mediator of gastric carcinogenesis, and evidence suggests that eosinophil recruitment may not only facilitate persistence but may also influence tumor progression.13 Investigations examining cytokine responses to the 30-kDa antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis have implicated p38 and ERK signaling as critical mediators of CCL2 expression,14 similar to our current results. Recruited eosinophils release cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β, which is involved in tissue remodeling and fibrosis. In chronically inflamed gastric tissue, proliferation of mesenchymal tissue can replace glandular tissue, leading to gastric atrophy, a lesion with premalignant potential for intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Thus, H. pylori–induced MAPK-dependent recruitment of eosinophils and subsequent release of fibrogenic cytokines may lower the threshold for cancer development at both early (gastritis) and later (gastric atrophy) steps in the cascade to gastric carcinogenesis.

In conclusion, our current results have defined mechanisms through which H. pylori enhance eosinophil recruitment to colonized gastric mucosa, which may play a significant role in pathogenesis and disease.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants CA 116087, CA 77955, and DK 58587 (R.M.P.) and DK 058404 (Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center).

T.A.N. and S.S.A. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Peek R.M., Jr, Blaser M.J. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nature Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwok T., Zabler D., Urman S., Rohde M., Hartig R., Wessler S., Misselwitz R., Berger J., Sewald N., Konig W., Backert S. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 2007;449:862–866. doi: 10.1038/nature06187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viala J., Chaput C., Boneca I.G., Cardona A., Girardin S.E., Moran A.P., Athman R., Memet S., Huerre M.R., Coyle A.J., DiStefano P.S., Sansonetti P.J., Labigne A., Bertin J., Philpott D.J., Ferrero R.L. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allison C.C., Kufer T.A., Kremmer E., Kaparakis M., Ferrero R.L. Helicobacter pylori induces MAPK phosphorylation and AP-1 activation via a NOD1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;183:8099–8109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe T.A.N., Fichtner-Feigl S., Gorelick P.L., Tsuji Y., Matsumoto Y., Chiba T., Fuss I.J., Kitani A., Strober W. NOD1 contributes to mouse host defense against Helicobacter pylori via induction of type I IFN and activation of the ISGF3 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1645–1662. doi: 10.1172/JCI39481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding S.Z., Olekhnovich I.N., Cover T.L., Peek R.M., Jr., Smith M.F., Jr., Goldberg J.B. Helicobacter pylori and mitogen-activated protein kinases mediate activator protein-1 (AP-1) subcomponent protein expression and DNA-binding activity in gastric epithelial cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53:385–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGovern T.W., Talley N.J., Kephart G.M., Carpenter H.A., Gleich G.J. Eosinophil infiltration and degranulation in Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF01298871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wedemeyer J., Vosskuhl K. Role of gastrointestinal eosinophils in inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:537–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien D.P., Romero-Gallo J., Schneider B.G., Chaturvedi R., Delgado A., Harris E.J., Krishna U., Ogden S.R., Israel D.A., Wilson K.T., Peek R.M., Jr. Regulation of the Helicobacter pylori cellular receptor decay-accelerating factor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23922–23930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801144200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moorchung N., Srivastava A.N., Gupta N.K., Malaviya A.K., Achyut B.R., Mittal B. The role of mast cells and eosinophils in chronic gastritis. Clin Exp Med. 2006;6:107–114. doi: 10.1007/s10238-006-0104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Argent R.H., Thomas R.J., Letley D.P., Rittig M.G., Hardie K.R., Atherton J.C. Functional association between the Helicobacter pylori virulence factors VacA and CagA. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:145–150. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tegtmeyer N., Zabler D., Schmidt D., Hartig R., Brandt S., Backert S. Importance of EGF receptor: HER2/Neu and Erk1/2 kinase signalling for host cell elongation and scattering induced by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein: antagonistic effects of the vacuolating cytotoxin VacA. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:488–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murdoch C., Muthana M., Coffelt S.B., Lewis C.E. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H.M., Shin D.M., Kim K.K., Lee J.S., Paik T.H., Jo E.K. Roles of reactive oxygen species in CXCL8 and CCL2 expression in response to the 30-kDa antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:46–56. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]