Abstract

The decision to remove or refold oxidized, denatured, or misfolded proteins by heat shock protein 70 and its binding partners is critical to determine cell fate under pathophysiological conditions. Overexpression of the ubiquitin ligase C-terminus of HSC70 interacting protein (CHIP) can compensate for failure of other ubiquitin ligases and enhance protein turnover and survival under chronic neurological stress. The ability of CHIP to alter cell fate after acute neurological injury has not been assessed. Using postmortem human tissue samples, we provide the first evidence that cortical CHIP expression is increased after ischemic stroke. Oxygen glucose deprivation in vitro led to rapid protein oxidation, antioxidant depletion, proteasome dysfunction, and a significant increase in CHIP expression. To determine if CHIP upregulation enhances neural survival, we overexpressed CHIP in vitro and evaluated cell fate 24 h after acute oxidative stress. Surprisingly, CHIP overexpressing cells fared worse against oxidative injury, accumulated more ubiquitinated and oxidized proteins, and experienced decreased proteasome activity. Conversely, using small interfering RNA to decrease CHIP expression in primary neuronal cultures improved survival after oxidative stress, suggesting that increases in CHIP observed after stroke like injuries are likely correlated with diminished survival and may negatively impact the neuroprotective potential of heat shock protein 70. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1787–1801.

Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are highly conserved, abundantly expressed proteins with diverse functions, including the assembly of multiprotein complexes, transport of nascent polypeptides, and regulation of protein folding (25). The HSP70 family also has broad neuroprotective properties under conditions of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, ischemia, and reperfusion, as well as in states of chronic neuronal stress (16, 26, 28). These protective functions have been attributed to the binding and sequestering of activated caspases and other cell death proteins (4, 32).

HSP70 is the major stress-inducible chaperone and is upregulated with thermal stress, oxidative injury, and after various acute and chronic insults (10). HSP70 operates as part of a multiprotein complex where associated co-chaperones can alter the function of the complex (3, 22, 41). For example, the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP competes with HSC70 organizing protein (HOP) for C-terminal HSP70 binding, whereas BCL2-associated anthanogene 1 (BAG-1) competes with HSC70 interacting protein (HIP) for N-terminal HSP70 binding. The formation of the HIP/HSP70/HOP is thought to direct HSP70 activity toward protein refolding, whereas the CHIP/HSP70/BAG-1 complex promotes client protein ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (3, 22).

The 26S proteasome is the major intracellular non-lysosomal proteolytic system essential for the rapid elimination of damaged proteins. The proteasome recognizes proteins that have been targeted for degradation via the interaction of the ubiquitin activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligating enzymes (E3) (9). Aberrant protein folding and trafficking as well as perturbations of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway have been associated with chronic neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's diseases (39). While protein aggregates are commonly observed in chronic neurodegenerative diseases, they have also been increasingly recognized as a pathological hallmark of acute neurological injury, including ischemia (52).

We have increasingly come to appreciate that HSP70 and CHIP are critical regulators of neuronal cell fate after injury. CHIP is a multifunctional ubiquitin ligase and its overexpression has been shown to afford neuroprotection by enhancing HSP70 client degradation activity (15). Other functions of CHIP include its ability to act as an autonomous molecular chaperone blocking proteotoxic stress (43) as well as a regulator of HSP70 expression (41). CHIP is also capable of impeding cell death associated with severe endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (23), suggesting that CHIP overexpression positively influences survival against chronic stress. While HSP70 induction is a common feature of neurological injury, alterations in CHIP expression after stress have not been evaluated in acute human neurological disorders and the ability of CHIP to alter cell survival after acute ischemic stress has not been assessed.

As stroke is the third leading cause of death and serious adult disability in the United States (42), identifying positive regulators of cell fate is essential for designing safe and effective neurotherapeutics.

In this work, we provide the first evidence that CHIP is upregulated in postmortem tissue from patients after transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or stroke, and we examined the effects of CHIP overexpression on cell survival after acute oxidative injury in vitro. Unlike chronic diseases, CHIP overexpression impairs neuronal survival and is associated with a loss in proteasome activity as well as increased levels of ubiquitinated and oxidized proteins in neural cells after oxidative stress. Moreover, silencing CHIP increased neuronal tolerance to oxidative injury, suggesting that sustained CHIP overexpression is harmful for neural survival. These data suggest that strategies to enhance CHIP activity and expression may have previously unappreciated deleterious consequences in acute neurological injuries.

Materials and Methods

User-friendly versions of all protocols and procedures in this work can be found on our lab website (www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/root/vumc.php?site=mclaughlinlab&doc=17838).

Reagents

XT-MOPS running buffer, Tris/Glycine transfer buffer, Criterion Bis-Tris gels, Laemmli buffer, and precision plus protein all blue standards were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories. Membrane-blocking solution was from Zymed. Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus was from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Inc., and Hybond P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes from GE Healthcare. Gel Code Blue Stain Reagent was obtained from Thermo Scientific.

For Western blots and immunofluorescence, the antibody to ubiquitinated proteins (Clone Fk2, PW8810) was purchased from Biomol. CHIP (PC711) antibody was purchased from Calbiochem. HSP40 antibody (SPA-400), HSP70 (HSP72) antibody (SPA-811), HSC70 antibody (SPA-816), and HSP90 antibody (SPA-830) were purchased from Assay Designs. The c-myc (9E10) antibody (sc-40) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. The glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase monoclonal antibody (AM4300) was purchased from Applied Biosystems/Ambion.

For tissue culture, fetal bovine serum was from Hyclone, and penicillin/streptomycin was obtained from Cambrex Bio Science. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, 11995) with high glucose, minimum essential medium (MEM, 51200), 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA 1×, trypan blue stain 0.4%, and hygromycin B in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 50 mg/ml) were purchased from Invitrogen.

Unless otherwise stated, all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Postmortem tissue

Dr. Rashad Nagra of the VA West Los Angeles Healthcare Center kindly provided postmortem human samples of cerebral cortex from the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center. Three patient categories were developed based on neuropathological diagnosis and available clinical data. Control cerebral cortical samples were obtained from subjects with no history of neurological disease and where cause of death was cancer without evidence of metastasis to the brain (prostate, breast, bladder, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma) (see Table 1 for patient data and postmortem interval [PMI]). The TIAs or subacute stroke category was compiled using patients who had a clinical history of TIAs where cause of death was attributed to other diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and congestive heart failure) or accidental death. These specimens had no cortical neuropathological lesions that were classified as being larger than microinfarctions or injury to the vasculature. Thickening of the vascular walls in both small and large vessels was, however, evident in several samples. Sections were matched for dissection region with subjects in the stroke category. The stroke category was comprised of patients who suffered non-hemorrhagic strokes associated with occlusion of the middle cerebral artery based on at least two of the following findings: clinical manifestations, imaging, or postmortem placement of plaques/emboli. The average patient age was 74.3 ± 2.94 years, and the average PMI was ≤15 h.

Table 1.

Human Tissue Diagnosis and Postmortem Interval

| HSB number | Sex | Diagnosis | Age | Average (x) | Postmortem interval | x | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3565 | M | Cardiomyopathy | 76 | 11 | ||

| Control | 3346 | F | Congestive heart failure | 91 | 10 | ||

| Control | 3371 | M | Lung cancer | 52 | 16 | ||

| Control | 3397 | F | Breast cancer | 73 | 20 | ||

| Control | 3406 | F | Congestive heart failure | 72 | 73 | 20 | 15 |

| Stroke | 1714b | F | Stroke; hypertension | 80 | 3 | ||

| Stroke | 2113 | M | Massive right frontal stroke | 82 | 4 | ||

| Stroke | 2264 | M | Stroke; diabetes mellitus | 61 | 10 | ||

| Stroke | 3968 | F | Stroke; middle cerebral artery | 81 | 14 | ||

| Stroke | 3132 | M | Large cerebral infarction | 53 | 71 | 20 | 10 |

| TIA | 2435b | F | TIA; mild supranuclear palsy | 76 | 7 | ||

| TIA | 1947 | F | TIA; Alzheimer's disease | 78 | 9 | ||

| TIA | 1718 | F | TIA; dementia | 75 | 10 | ||

| TIA | 3333 | F | Strokes, mini, COPD | 89 | 19 | ||

| TIA | 2528b | F | Cerebral vascular infarction, chronic | 76 | 79 | 20 | 13 |

TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Primary neuronal cell culture

Primary cortical cultures were prepared from embryonic day 18 Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described with modest adaptations (34). Briefly, cortices were dissociated and the resultant cell suspension was adjusted to 335,000–350,000 cells/ml. Cells were plated 2 ml/well in 6-well tissue culture plates containing one 25 mm poly-L-ornithine-coated coverslip per well. Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in the growth medium composed of a volume to volume mixture of 84% DMEM, 8% Ham's F12-nutrients (11765; Sigma-Aldrich), 8% fetal bovine serum, 24 U/ml penicillin, 24 μg/ml streptomycin, and 80 μM L-glutamine. Glial proliferation was inhibited after 2 days in culture with 1-2 μM cytosine arabinoside, after which cultures were maintained in Neurobasal medium (21103; Invitrogen) containing B27 (17504-044; Invitrogen) and NS21 supplements (7) with antibiotics.

Neuronal oxygen glucose deprivation

Oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) experiments were preformed when cells were at least 2 weeks old (14–20 days in vitro), at which time point neurons represent at least 95% of the population as assessed by neuronal nuclei and glial fibrillary acidic protein staining (35). OGD was performed essentially as described (21) by complete exchange of the medium with deoxygenated, glucose-free Earle's balanced salt solution (150 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES; pH 7.3), bubbled with 10% H2/85% N2/5% CO2. Cultures were exposed to hypoxia in an anaerobic chamber (Billups-Rothberg) for various durations of time (5–90 min) at 37°C. Upon OGD termination, cells were washed with MEM/BSA/HEPES (0.01% BSA and 25 mM HEPES) and maintained in MEM/BSA/HEPES/2xN2 until cell viability was determined 18–24 h later using a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-based in vitro toxicity assay kit. Toxicity data were represented as averaged raw LDH values. As a positive control for inducing total neuronal degeneration, cultures were exposed to 100 μM N-methly-d-aspartate (NMDA) and 10 μM glycine in MEM/BSA/HEPES/2xN2 for 60 min. We have previously shown that these conditions induce total neuronal degeneration (32). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis to assess significant deviations from control.

Protein extract preparation

Protein extracts from primary neurons were prepared 24 h after exposure to OGD as previously described (32). After harvest in tris-based lysis buffer, a 150 μl aliquot was placed into a new Eppendorf tube containing dithiothreitol (50 mM) (DTT; D9779, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for the determination of total oxidized proteins as described in the OxyBlot methodology below.

Glutathione and oxidized glutathione measurement by high-performance liquid chromatography

To determine the consequences of OGD on antioxidant defenses, intracellular glutathione (GSH) concentrations were measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (48). After OGD, cultures were extracted with 5% perchloric acid/0.2M boric acid. Acid-soluble thiols were derivatized with iodoacetic acid and dansyl chloride and were analyzed by HPLC using a propylamine column (YMC Pack, NH2, Waters) and an automated HPLC system (Alliance 2695, Waters). The GSH and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) concentrations were normalized to protein content (Bio-Rad).

Determination of total oxidized protein levels using OxyBlot methodology

Derivatization of oxidized proteins was performed using the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, after addition of 50 mM DTT samples were divided into the derivatization reaction (DR) containing 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine and the negative control (NC) solution. Samples were stored at 4°C and run within 7 days. Equal protein concentrations were separated using 4–12% Criterion Bis-Tris gels and processed as described in the Immunoblotting section below. Antibodies specific for the detection of oxidized proteins were provided by the manufacturer.

Oxidative stress model of neural injury in HT-22 cells

HT-22 cells were derived from the immortalized H4 hippocampal murine neuroblastoma cell line, and were a generous gift from Pamela Maher (Salk Institute). This neural cell line was chosen because HT-22 cells are a well-characterized model of neural oxidative injury (30, 46). These cells undergo oxidative stress-induced toxicity upon exposure to glutamate, which blocks glutamate-cystine antiporters in the plasma membrane, resulting in GSH deficiency and oxidative cell death (46). HT-22 cells were maintained in DMEM with glutamine, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (0.2%). The CHIP overexpressing cell line, CHIP-6B, which we refer to as CHIP overexpressing, was derived by stable transfection with a full-length human CHIP cDNA with a myc-tag in a hygromycin-resistant vector and has been previously described (49). The medium for these HT-22 derived neural cells was supplemented with 50 mg/ml hygromycin B. Cells were grown in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passed by trypsinization when the cells' confluency reached 50%–80% (13).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (33). Semiquantitative analyses of immunoblots were performed and were noted per our previously described method by performing high resolution scans for densiometric quantification with Scion NIH IMAGE J. Values are expressed as mean increase above control levels (±SEM), and statistical analysis was performed by using two-tailed t-tests (32).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in 10% formaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 as we have previously described (17). For detection of ubiquitinated proteins, Fk2 (1:200) primary antibody was diluted in 1% BSA overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed with 1xPBS for a total of 30 min and incubated in cy-3 secondary antibody (1:500) for 60 min at room temperature. Cells were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPi) to observe nuclei. Coverslips were mounted and fluorescence was observed with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope. Cells that were loaded with propidium iodide (PI) were fixed in 10% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and counterstained with DAPi.

Proteasome activity measurement

To determine the consequences of chronic CHIP overexpression on protein turnover, the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome was measured by means of fluorogenic peptide substrates. Both neural lines were plated at a density of 100,000 cells per well in 6-well plates, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight. The following day, cells were exposed to glutamate (3 mM) to induce oxidative stress or to Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al (MG132; 10 μM) to inhibit proteasome activity (46). Oxidative stress was terminated by placing culture dishes on ice and scraping cells into the culture medium with a rubber policeman. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1,141 g and 4°C for 10 min. After removal of the supernatant, the pellet was washed carefully with ice cold 1xPBS, and resuspended in 400 μl lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM ATP, 0.035% SDS, and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.8). Fifty microliters of each sample was reserved for a protein assay, and the remaining 350 μl was used to determine proteasome activity. Addition of 40 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC to each sample was followed by a 30 min incubation in a 37°C water bath. The reaction was terminated by adding 13 μl ethanol and 87.5 μl ddH2O to quench the substrate. Hundred microliter aliquots from each sample were then added to a white 96-well plate (Corning Incorporated) in quadruplicate. Fluorescence was measured by using a SpectraFluorPlus plate reader at 360 nm excitation, 465 nm emission after a 3 s premeasurement delay, and a 40 μs integration time. All data represent the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments.

For the assessment of the chymotrypsin-like activity in neuron-enriched primary cultures, mature neurons were exposed to OGD as described above and extracts were prepared by placing plates on ice, then carefully washing cells twice with ice-cold 1xPBS and harvested as above in lysis buffer. Fifty microliters of each sample was reserved for a protein assay. The remaining 350 μl was used for the assessment of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome as described above. All data represent the mean ± SEM of four to seven independent experiments.

Glutamate toxicity assay in neural cells

Both neural cell lines were plated at a density of 30,000 cells per well in 24-well plates and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight. The following day, cells were treated by exchanging the medium with 0.5 ml medium containing glutamate (1, 3, or 5 mM) and glycine (10 μM). Sorbitol (1 M) solution was prepared in the culture medium to induce total cell death. Twenty-four hours after incubation at 37°C, cellular viability was photodocumented and assessed with an in vitro thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) toxicology assay as previously described (38). All data represent the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments.

Transfections of neural cells and primary cortical neurons with CHIP siRNA

All small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were obtained from QIAGEN Science. The CHIP siRNA sequence used for experiments in HT-22 cells was 5′-CCCACTTGTGGCAGTGTACTA-3′. The CHIP siRNA sequence used for experiments in primary neuronal cultures was 5′-CCAGCTGGAGATGGAGAGTTA-3′. Amaxa reagents for the nucleofector electroporation were obtained from Lonza. Because of their high transfection efficiency (80%–90%), we used HT-22 cells for the biochemical determination of optimal CHIP knockdown. CHIP siRNA transfected cells were harvested at 24–72 h posttransfection and extracts were prepared for immunoblotting as described above.

For the transfection of HT-22 cells, the Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (VCA-1001, Lonza) was used following manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, HT-22 cells were grown to a 80% confluency, then trypsinized, and centrifuged at 1,141 g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml plating medium; cells were counted and adjusted to a final density of 1 × 106 cells per nucleofection sample. Cells were compacted by centrifugation at 1.141 g for 10 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl Cell Line Nucleofector solution. CHIP siRNA (25 nM) and green-fluorescent protein (GFP) (2 μg) were added to 97.5 μl of cell suspension and electroporated using Nucleofector program U-030. Cells were immediately placed in a 1:15 dilution of Hank's balanced salt solution for 10 min. Five hundred microliters of the cell suspension was transferred into each well of a 6-well dish containing 2 ml of the growth medium. All experiments using CHIP siRNA were conducted 72 h after transfection, as pilot experiments revealed this to be the amount of time needed for optimal knockdown of CHIP expression (Fig. 1).

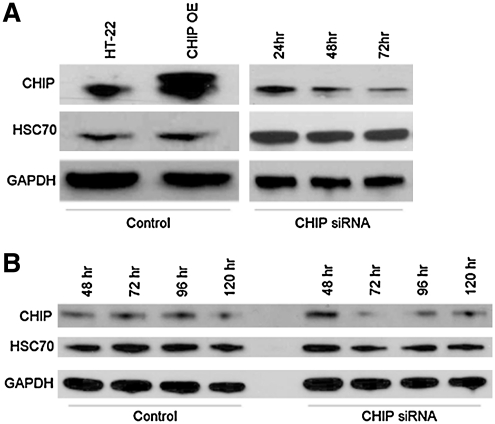

FIG. 1.

Optimal CHIP knockdown is achieved 72 h after transfection. (A) HT-22 cells and (B) young primary neurons were transfected with CHIP siRNA using the nucleoporation methodology. Cells were harvested at various time points post-transfection, and proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and probed with antibodies specific for CHIP, HSC70, or GAPDH. Optimal CHIP knockdown was achieved 72 h after transfection in both model systems. Comparable results were obtained in three additional independent experiments. CHIP, C-terminus of HSC70 interacting protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HSC70, heat shock cognate 70.

Subsequent neuronal siRNA experiments were performed as described above with the protocol modified to use the Rat Neuron Nucleofector Kit (VCA-1003, Lonza) and the Nucleofector program O-03. After the 10 min re-equilibration period, 250 μl of the cell suspension was plated into each well of a 6-well plate containing 2 ml of the growth medium. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells underwent a complete medium change.

Induction of oxidative injury in primary cortical cultures

To determine if neurons had altered vulnerability to acute oxidative injury when CHIP expression was decreased, young primary neurons (3 days in vitro) were exposed to glutamate (3 mM) for 9 h 3 days (72 h) after transfection with CHIP siRNA. Coverslips of CHIP siRNA transfected and control cortical cultures were transferred into a 24-well plate containing control or toxicity medium. Oxidative injury was induced by exchanging the growth medium with 0.5 ml MEM/BSA/HEPES medium containing glutamate (3 mM) and glycine (10 μM). Staurosporin (0.5 μM) was used as a positive control for cell death in these experiments. Upon treatment termination, cells were incubated with PI (10 μM) (P4170; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in MEM/BSA/HEPES for 10 min, fixed, and counterstained with DAPi. Cell viability was assessed by counting the number of neurons that were positive for PI and that showed chromatin condensation using DAPi staining.

Quantification of cell death in siRNA transfected neurons

The percentage of PI-positive cells in CHIP siRNA-transfected and control primary cultures after induction of oxidative injury was determined by cell counting. Neurons undergoing cell death were identified by nuclei with chromatin condensation as well as by intense PI staining. Counts were performed by individuals blinded to the treatment conditions. Three to five fields of view per coverslip from a total of 10–12 coverslips per condition were quantified as we have previously described (1). All data represent the average ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Results

CHIP levels are increased in human tissue after hypoxic injury

Overexpression of CHIP has been shown to be neuroprotective in animal and cell culture models of chronic neurodegenerative disorders, an effect that has been attributed to CHIP's E3 ligase activity by which damaged proteins are targeted for proteasomal degradation (23, 44). To evaluate if CHIP was altered by acute central nervous system injury, we compared the expression profiles of CHIP as well as HSP70 and HSC70 in postmortem human cerebral cortical tissue samples from individuals with no history of neurological injury (Control), those who had a recent history of transient ischemic attacks (TIA), or those who suffered from a fatal stroke (Stroke) due to the occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (Fig. 2A). Prior work has demonstrated that both the CHIP and HSP70 proteins are stable with postmortem intervals of up to 24 h (44). Therefore, only samples with a PMI shorter than 23 h were included in this study. Patients were matched for PMI and gender with an average age of 74 (see Table 1).

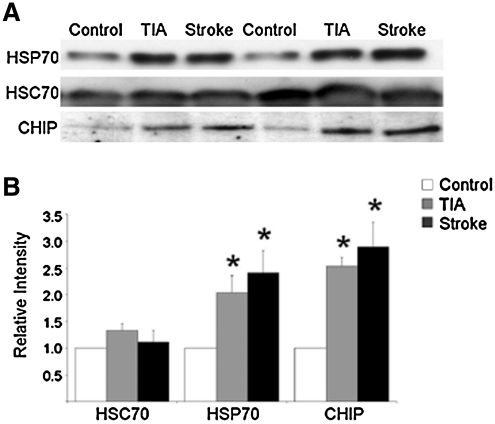

FIG. 2.

Hypoxic injury results in increased expression levels of HSP70 and CHIP in human tissue. (A) Postmortem specimens from patients who had experienced a fatal ischemic stroke of the middle cerebral artery (Stroke), history of TIA, or died from causes that were not associated with hypoxia, ischemia, or neurological compromise (Control) were probed for HSP70, the constitutively active chaperone HSC70, or CHIP. Twenty micrograms of protein was run in each lane and blots are representative of results obtained from five independent sample sets. (B) Alterations in protein expression were quantified by performing high-resolution scans for densitometric quantification with Scion NIH IMAGE J. Equal protein loading was ensured by protein assays and equal expression of HSC70. Values are expressed as means (±SEM) of five independent sample groups. *Statistical significance compared to control as determined by two-tailed t-test with p < 0.05. For detailed information on PMI, age, sex, and cause of death, see Table 1. TIA, transient ischemic attack; CHIP, C-terminus of HSC70 interacting protein; HSC70, heat shock cognate 70; HSP70, heat shock protein 70.

Using a total sample size of five patients from each group, we observed a significant increase in HSP70 expression levels in the cerebral cortex in both TIA and stroke samples compared to control tissue (Fig. 2B). The constitutively expressed form of the HSP70 family, HSC70, was not altered and was used as a loading control as previously described (32). We also observed a significant increase in CHIP expression levels in both TIA and stroke tissue (Fig. 2B).

GSH levels are decreased and oxidative protein damage is increased after neuronal exposure to OGD

To determine if the observed upregulation of CHIP was neuroprotective in an acute injury setting, we moved to a more pliable in vitro model of stroke. Mature neuron-enriched cultures were exposed to OGD for 5, 15, or 90 min followed by a 24 h recovery period. Representative photomicrographs of neurons exposed to OGD for 5 and 15 min demonstrate many healthy phase-bright neurons (Fig. 3A, B). Neurite retraction and a loss of phase-bright somas was evident after exposure to OGD for 90 min (Fig. 3C). These architectural changes were associated with a loss of viability as assessed by the release of the essential cytosolic enzyme LDH. Neither 5 nor 15 min OGD significantly increased LDH levels, whereas 90 min OGD induced cell death comparable to the 100% neurotoxicity observed in neurons that were exposed to 100 μM NMDA/10 μM glycine for 60 min (Fig. 3D) (32). We decided to use 100 μM NMDA to induce total cell death in our neuron enriched cultures, as previous studies have shown that exposure of neurons to 50 μM NMDA for 5 min is neurotoxic, whereas exposure to 100 μM NMDA results in 100% cell death at 24 h (8, 36, 47).

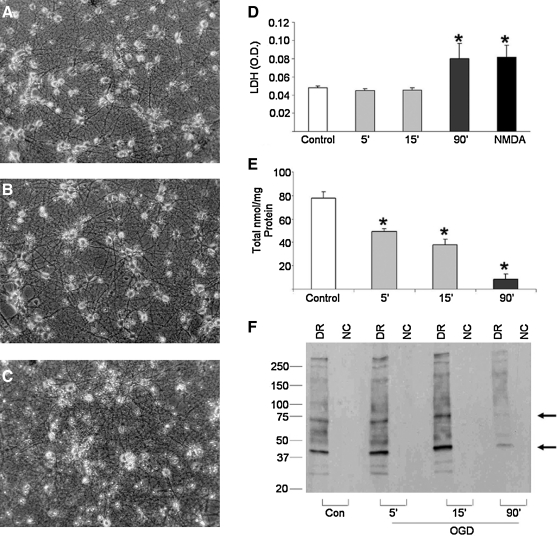

FIG. 3.

Neuronal exposure to OGD impairs antioxidant defenses and increases oxidative protein damage. Neuron-enriched primary cultures were exposed to OGD for 5–90 min and cell survival was determined by visually inspecting cells under phase-bright microscopy. Representative photomicrographs of cultures 24 h after the termination of (A) 5 min or (B) 15 min of OGD demonstrate many healthy phase-bright neurons with elaborate processes. Neurons exposed to OGD for (C) 90 min show loss of phase-bright somas and neurite retraction 24 h after OGD. (D) Cell viability was further assessed 24 h after OGD using an in vitro toxicology kit measuring the release of LDH from dead and dying neurons. Data demonstrate an increase in cell death as the duration of neuronal exposure to OGD increased. (E) Total glutathione levels were measured by the high performance liquid chromatography methodology 24 h after termination of OGD. Results reveal a significant decrease in total glutathione levels after OGD. (F) Oxidative protein damage was assessed using the OxyBlot methodology 24 h after termination of OGD. Levels of oxidized proteins increased after mild and modest OGD particularly in the 40 and 70 kDa ranges (arrow), but decreased robustly after lethal OGD. All data are expressed as means (±SEM) of four to seven independent experiments run in duplicate. *p < 0.05 using a one-tailed ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc analysis. DR, derivatization reaction; OGD, oxygen glucose deprivation; NC, negative control; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NMDA, N-methly-d-aspartate.

Enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathophysiology of many neurological disorders, including ischemic stroke (6, 37). Cells are able to counteract the deleterious effects of ROS under normal conditions via the activity of cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms, including the main cellular antioxidant GSH (30, 37). To assess if mild ischemic conditions were inducing antioxidant stress, we assessed total GSH levels 24 h after 5, 15, or 90 min of OGD. We observed a significant depletion of GSH levels, which was exacerbated with increasing OGD duration (Fig. 3E).

We next assessed ROS damage to proteins by detection of protein carbonyl group formation (12) and observed a moderate increase in total oxidized protein levels as well as an apparent increase in oxidation levels of proteins in the 40 and 70 kDa ranges (arrow) (Fig. 3F). We did not, however, observe an increase in protein oxidation at the 24 h time point after neuronal exposure to lethal ischemia (90′) (Fig. 3F). We believe that this result reflects the unrecoverable nature of this insult, inducing massive cell death within hours. This observation is supported by preliminary time course analyses using OxyBlot methodology (3 and 6 h after OGD) where severe OGD resulted in increased protein carbonyl formation (data not shown).

Neuronal exposure to OGD increases protein ubiquitination and alters proteasome function but does not robustly increase CHIP expression in vitro

As an E3 ubiquitin ligase, CHIP plays an important role in intervening after protein dysfunction via its ability to ubiquitinate damaged proteins, thereby targeting them for proteasomal degradation. Given the intensity of protein oxidation we observed in Figure 3F, we hypothesized that many of these oxidized proteins were likely to be tagged for proteasomal degradation. We therefore investigated if protein ubiquitination was altered after various durations of neuronal exposure to OGD. Using the Fk2 antibody, which detects mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins, we observed an increase in polyubiquitinated proteins, represented by a dark smear of higher molecular weight proteins 24 h after OGD. There was also a near-complete loss of monoubiquitinated protein species (arrow) after 90 min OGD, indicating that the majority of the cellular ubiquitin has been recruited to damaged proteins (Fig. 4A).

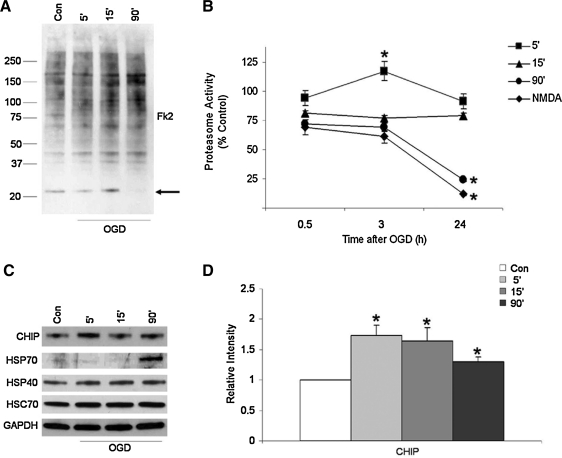

FIG. 4.

Neuronal OGD increases protein ubiquitination and alters proteasome function but does not substantially increase CHIP expression in vitro. Whole cell extracts of neuronal cultures were harvested 6 h after exposure to OGD. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and probed with antibodies specific to mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins (Fk2). (A) Protein polyubiquitination increased with prolonged exposure of neurons to OGD, while a near-complete loss of monoubiquitinated proteins is detected after lethal OGD (arrow). (B) Primary cultures were exposed to OGD for 5–90 min and harvested 30 min, 3 h, or 24 h after OGD, and proteasome activity was measured. Data represent the mean ± SEM for five independent experiments. *Statistical significance as determined by two-tailed t-test with p < 0.05. (C) Cells harvested 24 h after OGD show that CHIP expression levels are significantly increased after mild (5′) OGD, whereas HSP70 expression levels increase robustly after lethal (90′) OGD. Data are taken from representative experiments that were performed using at least four independent samples. (D) Alterations in CHIP protein expression were quantified by performing high-resolution scans for densitometric quantification with Scion NIH IMAGE J. Values are expressed as means (±SEM) of three independent culturing sessions. *Statistical significance compared to control as determined by two-tailed t-test with p < 0.05.

To determine if protein degradation was altered, we evaluated the effects of mild (5′), moderate (15′), or lethal (90′) OGD on neuronal proteasome activity. We observed that while mild OGD led to enhanced proteasome activity 3 h after the initial insult, it returned to baseline levels at 24 h. Moderate OGD did not affect proteasome activity at either time point we assessed, whereas lethal OGD and NMDA exposure resulted in a dramatic decrease in proteasome activity 24 h later (Fig. 4B). These data support a model in which the proteasome is able to clear damaged and ubiquitin-tagged proteins after mild ischemic stress, but protein turnover is dramatically impaired by lethal injury.

As we observed an increase in CHIP and HSP70 expression after TIA and stroke in humans, we next sought to determine if these changes were recapitulated in our in vitro system. Twenty-four hours after mild, moderate, or lethal OGD, CHIP levels were indeed significantly increased (Fig. 4C, D). Moreover, HSP70 was not substantially induced until we moved beyond a 15 min exposure, which we have shown to be the maximal subtoxic period of OGD that these cells can withstand (27) (Fig. 4C).

Chronic CHIP overexpression alters chaperone expression profiles after oxidative injury in vitro

Given that the increase in CHIP expression in our neuronal model was not as robust as in the postmortem human tissue samples, we next sought to determine if cell viability was enhanced in neural systems exposed to acute oxidative stress when CHIP was overexpressed. The HT-22 derived neural line was generated by placing a CHIP-myc construct into the HT-22 cell line. HT-22's are a neural hippocampal cell line, and a well-characterized model of neural oxidative injury (30, 46). These cells are easy to transfect, reproducibly undergo glutamate-induced toxicity, and have many of the signaling systems essential for mediating ischemic injury (30, 46, 49).

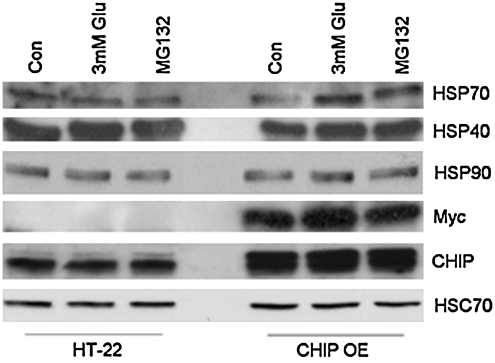

Given CHIP's function as a modulator of HSP70 expression and turnover (41), we first evaluated the effects of stable CHIP overexpression on expression profiles of inducible HSPs after acute oxidative injury by exposing neural cell lines to glutamate (3 mM) or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) for 3 h. We observed that HSP40 and HSP90 expression levels remained constant in the presence of glutamate in both neural lines while HSP70 levels increased in the HT-22 derived neural line upon exposure to glutamate. Myc and CHIP expression were used as positive controls to confirm the presence of the myc-tagged CHIP construct in this cell line (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

CHIP overexpression alters HSP expression profiles after oxidative injury. Both neural cell lines were treated with glutamate (3 mM) or proteasome inhibitor for 3 h, after which whole cell extracts were harvested and prepared for immunoblotting. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and probed with antibodies specific to HSP70, HSP40, HSP90, Myc, CHIP, or HSC70 as a loading control. Exposure to glutamate or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 both increased HSP70 levels in the HT-22 derived neural lines cells, whereas HSP40 and HSP90 expression levels remained constant in the presence of glutamate in these cells. Immunoblots represent results from five independent culturing sessions. MG132, Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al.

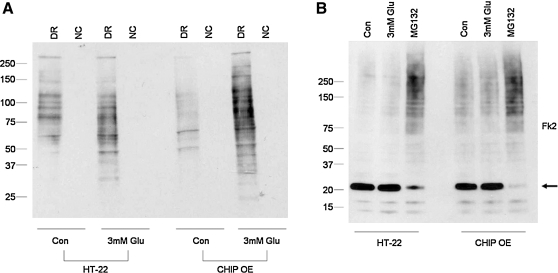

CHIP overexpression is associated with increased protein carbonyl formation after oxidative injury and enhanced baseline polyubiquitination

Given the extent of CHIP overexpression and HSP70 induction by stress, we next sought to determine if neural cells with chronically elevated CHIP levels experience alterations in the turnover of oxidized proteins. We exposed both neural cell lines to glutamate (3 mM) for 3 h after which cells were harvested and total protein carbonyl formation was examined. Under control conditions, HT-22 derived neural lines exhibited an apparent decrease in total protein oxidization compared to control cells. The presence of oxidized proteins increased in both cell types after exposure to glutamate but to a greater extent in the CHIP overexpressing cultures (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

CHIP overexpression increases protein carbonyl formation after exposure to glutamate and baseline protein ubiquitination. (A) Both neural cell lines were exposed to glutamate (3 mM) for 3 h, after which whole cell extracts were harvested and prepared for OxyBlotting. Exposure to glutamate results in higher levels of protein oxidation in HT-22 derived neural lines. (B) Both neural cell lines were treated with glutamate (3 mM) or proteasome inhibitor for 3 h, after which whole cell lysates were prepared for immunoblotting. Equal amounts of proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and probed for mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins using the Fk2 antibody. Results show increased levels of polyubiquitinated proteins in HT-22 derived lines cells at baseline. Proteasome inhibition results in a robust increase in polyubiquitinated protein levels along with a decrease in monoubiquitinated proteins (arrow) in both neural lines. Data represent results from five independent culturing sessions. DR, derivatization reaction; NC, negative control.

To determine if oxidized proteins were also being tagged for proteasomal degradation, we exposed both neural lines to glutamate (3 mM) or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) for 3 h after which cells were harvested and protein ubiquitination was analyzed by immunoblotting using the Fk2 antibody (Fig. 6B). We observed increased baseline levels of polyubiquitinated proteins in CHIP overexpressing cells represented by a smear of higher molecular weight proteins. Exposure of both neural cell types to the proteasome inhibitor MG132 resulted in a robust increase in polyubiquitinated proteins along with a decrease in monoubiquitinated protein levels (Fig. 6B; arrow), suggesting that the ubiquitin conjugating machinery in both cell lines was highly efficient.

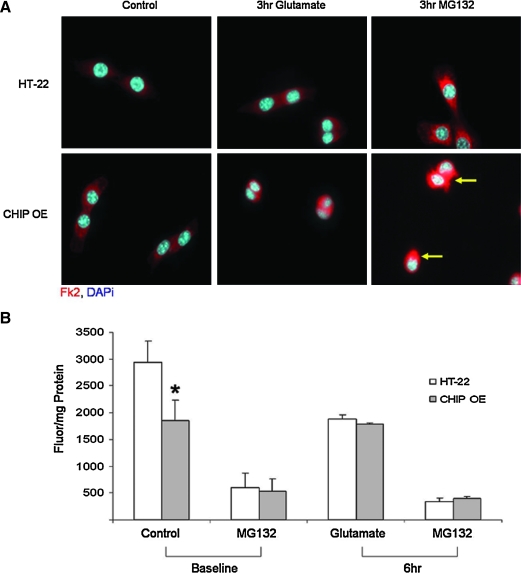

Exposure to oxidative injury results in an increase in ubiquitin inclusion bodies and a loss of proteasome activity in CHIP overexpressing cells

We next used immunofluorescence to evaluate the localization and morphology of ubiquitinated proteins in control and stressed cells. There was an appreciable increase in Fk2 staining after a 3 h exposure to either proteasome inhibition or oxidative challenge. Moreover, exposure to the proteasome inhibitor MG132 resulted in the formation of large, dense, cytosolic ubiquitin inclusion bodies that were predominantly localized in proximity to the nucleus in the HT-22 derived neural lines (arrow). This finding is consistent with the work by Dai et al. and Anderson et al., who demonstrate nuclear translocation of CHIP after exposure to stress (2, 11), thereby supporting CHIP's involvement in the stress response via its ability to interact with heat shock factor 1 and ultimately resulting in the induction of HSP expression (11, 41). In contrast, small, disperse inclusion bodies were observed in the cytosol of HT-22 cells (Fig. 7A). This staining is consistent with our biochemical assessment of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome in which we observed a significant loss of baseline proteasome function in the HT-22 derived neural line (Fig. 7B). A 6 h exposure to glutamate reduced proteasome activity equally in both neural lines (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that the chronic overexpression of CHIP decreases baseline proteasome activity, which is not toxic but results in the accumulation of damaged proteins within cells.

FIG. 7.

Exposure to oxidative injury leads to an increase in ubiquitin inclusion bodies and a loss of proteasome activity in CHIP overexpressing cells. (A) Cells were exposed to glutamate (3 mM) for 3 h in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM). Immunofluorescence was performed using an Fk2 antibody (red) to evaluate ubiquitinated proteins alongside DAPi (blue) to stain cell nuclei. The increase in ubiquitin aggregates in stressed cells overexpressing CHIP is highlighted with arrows. (B) Both cell lines were exposed to glutamate (3 mM) for 6 h and the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome was measured using the fluorescent substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC. CHIP overexpression results in decreased baseline proteasome activity. Data are expressed as fluorescence per mg protein and represent the (±SEM) of six independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. *Statistical significance as determined by two-tailed t-test with p < 0.05, n = 6. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

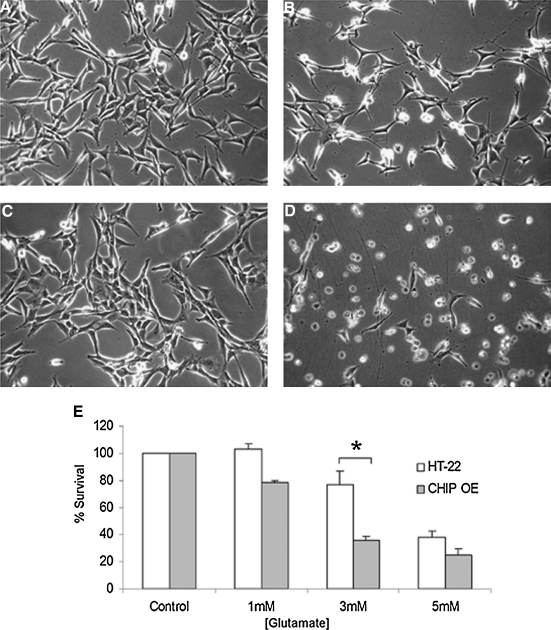

Chronic CHIP overexpression increases vulnerability to oxidative injury in vitro

Taken together, these data suggest that neural cells that stably overexpress CHIP experience a baseline level of protein turnover inhibition, which could alter cell fate in response to acute injury. To test this hypothesis, both cell lines were exposed to extracellular glutamate (1, 3, or 5 mM) and incubated for 24 h. Cells were visually inspected using phase microscopy and death was assessed by biochemical viability assays. Representative photomicrographs were taken 24 h later (Fig. 8A–D). Both cell lines underwent mitotic division at similar rates, as confirmed by Ki-67 staining (Stankowski, Cohen, and McLaughlin, unpublished observations), were adherent, and showed healthy cellular morphology (Fig. 8A, C). Exposure to 3 mM glutamate for 24 h increased cell detachment, neural shrinkage, and cell death, all of which were more pronounced in the HT-22 derived neural line (Fig. 8B, D). CHIP overexpression was associated with a 50% decrease in cell viability after exposure to glutamate (3 mM; Fig. 8E).

FIG. 8.

CHIP overexpression increases vulnerability to oxidative injury in vitro. Neural cell lines were treated with glutamate (3 mM) for 24 h after which cell viability was determined by visually inspecting cells under phase-bright microscopy. (A) Photomicrographs of control HT-22 cells, (B) HT-22 cells exposed to 3 mM glutamate for 24 h, (C) HT-22 derived neural control cultures, and (D) those exposed to 3 mM glutamate for 24 h. Note the loss of adherent cells in B and D compared to respective controls and enhanced neural shrinkage and pyknosis in HT-22 derived cells compared to HT-22 cells exposed to glutamate. (E) Both cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of glutamate for 24 h and cell viability was assessed with MTT assays. Data are expressed as percent survival compared to the control and represent the mean ± SEM of five independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. *Statistical significance as determined by two-tailed t-test with p < 0.05, n = 5.

Neuronal tolerance to acute oxidative injury is enhanced when CHIP expression is silenced

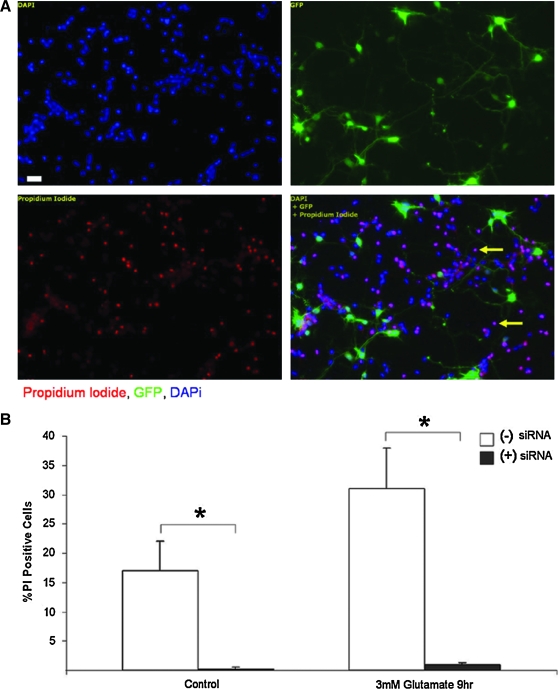

As chronic CHIP overexpression was deleterious to neural survival after acute oxidative stress, we next sought to determine if blocking CHIP expression would increase neuronal tolerance in this paradigm. Primary neuronal cultures were transfected with CHIP siRNA and a GFP reporter followed by exposure to glutamate (3 mM) 72 h later. The 72 h time point was chosen because pilot experiments using CHIP siRNA determined that optimal CHIP protein knockdown in primary neurons occurs at this time point (Fig. 1B). The 30% transfection efficiency we achieved with this system made it amenable to immunofluorescence and cell counting to assess injury but not to biochemical analysis. Three days after CHIP silencing, neurons were exposed to mild oxidative stress for 9 h followed by incubation in PI to assess neuronal viability. We observed PI uptake predominately in cells that were not transfected with CHIP siRNA or GFP (Fig. 9A, arrows). Cell counts revealed that 17% of the nontransfected cells were PI positive under control conditions, whereas only 1% of neurons in which CHIP expression levels were suppressed were positive for PI (Fig. 9B). This suggests that decreasing CHIP expression increases survival after electroporation and transfection stress. Nine hours after exposure to acute oxidative injury, there was a significant increase in cells that took up PI. Thirty percent of nontransfected cells were positive for the cell death marker, whereas decreased CHIP levels dramatically improved survival with only 2% of green transfected cells also including the red staining of PI (Fig. 9A). Taken together, these data suggest that reducing CHIP expression levels renders neurons more resistant to acute oxidative injury.

FIG. 9.

Decreasing CHIP expression enhances neuronal tolerance to oxidative stress. (A) Primary cultures were transfected with CHIP siRNA upon dissociation and plated. After 72 h, cells were exposed to glutamate (3 mM) for 9 h followed by incubation in PI (10 μM) for 10 min and fixed for immunofluorescent analysis of PI uptake (red) in cells that received CHIP siRNA (green). See Figure 1B for verification of decreased CHIP expression in neurons induced by siRNA electroporation optimized to 72 h. (B) Quantification of the percent of nontransfected and CHIP transfected neurons positive for the cell death marker PI. Cell counts performed by three independent investigators of >1500 neurons revealed a significant decrease in PI uptake in neurons transfected with CHIP siRNA after exposure to acute oxidative stress. Results represent data from three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by two-tailed ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis performed on a group effect with *p < 0.05. Scale bar = 100 μM. PI, propidium iodide; siRNA, small interfering RNA. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Discussion

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States with 88% of all stroke cases being ischemic in nature (42). The cellular and molecular mechanisms associated with neuronal death after ischemic stroke have been extensively studied. Yet, we have failed to design effective neurotherapeutics that can increase neuronal survival (19). Although many preclinical studies have demonstrated the neuroprotective effects of HSP70 (45, 50), we are only beginning to understand the mechanisms by which protection is afforded.

The major protective effects of the HSP70 chaperone complex are associated with sequestering activated proteases and enhancing protein refolding and degradation (18). The ability of cells to monitor the folding status of newly synthesized proteins via the help of HSPs, including HSP70 and HSP90, thereby assuring the preservation of native protein conformations, is essential for cellular survival (20). Although it was traditionally perceived that HSP70 and HSP90 work together to determine protein fate, recent studies by Yoichi Osawa's group demonstrate a refined version of this classical model by proposing that HSP90 and HSP70 engage in opposing roles in protein triage decisions (40). Specifically, the updated model by Pratt et al. proposes that HSP90 is the first molecular chaperone to act on a client protein and to govern protein triage via HSP90's ability to interact with ligand binding clefts, which open in response to oxidative damage, leading to the exposure of hydrophobic protein residues (40). The interaction between HSP90 and the open protein cleft is suggested to prevent further unfolding of the protein. If, however, protein unfolding reaches a degree that can no longer be controlled by HSP90's cycling activities, the client protein is sent to the HSP70 complex, which can then direct these proteins toward either the refolding or the degradation pathway through its association with various co-chaperone networks (3, 22, 40).

Recently, increased attention has been drawn to the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP as a possible target for neurotherapeutic development. This dual-function cochaperone/E3 ligase has been predominantly studied in the context of chronic neurodegenerative diseases, supporting a model whereby CHIP overexpression enhances the degradation of damaged proteins and substitutes for the loss of other ubiquitin ligases, thereby providing neuroprotection (23, 44). In addition to studies investigating the role of CHIP on cellular survival in the central nervous system, Zhang et al. demonstrate a protective role of CHIP in the context of myocardial infarction (51). These findings underline the fact that CHIP's benefits are not restricted to the brain and that CHIP can potentially be considered as a target for the development of therapeutics for a variety of diseases. Moreover, Zhang et al. present data that are opposite to our here-presented findings, as this group demonstrates that the presence of CHIP offers cardioprotection after myocardial infarction (51), whereas our data show increased neuronal death after acute ischemic injury in the presence of high CHIP levels. Overall, these results underscore the complexity of CHIP, whereby organs respond differently to varying levels of this E3 ubiquitin ligase after different types of injury.

Although the majority of studies investigating CHIP function have focused on its role in chronic neurodegenerative diseases, CHIP's role in determining cell fate in acute neurological disorders has not been assessed. In order for CHIP to target damaged proteins for degradation, it interacts with HSP70 and HSP90. HSP upregulation is a common feature in both acute and chronic neurological diseases and the expression levels of HSPs, including HSP70 and HSP90, have been shown to be increased after cerebral ischemia (14).

Given our observation that CHIP is upregulated in patients who suffered TIA or stroke, one may infer that the cellular response to acute injury is far more complex than previously appreciated, involving not only the upregulation of HSP70, but more so the upregulation of entire chaperone networks. Further, we hypothesize that the energetic status of neurons after mild or moderate insults versus lethal insults plays an important role in determining cellular outcome. That is, neuronal ATP levels are increased after mild OGD, and drastically decreased after lethal OGD (Zeiger and McLaughlin, unpublished observation), suggesting that cells contain sufficient ATP after a mild insult in order for molecular chaperones and the proteasome to work efficiently. In contrast, we predict that the lack of energy reserves after lethal OGD prevents protein quality control systems from properly assembling chaperone networks that normally promote damaged protein removal and support proteasome activity.

To our knowledge, our results are the first evidence that CHIP expression levels are increased in the human cerebral cortex after ischemic stroke. While our neuronal in vitro model is a reproducible and accessible platform to mimic TIAs and stroke, the degree of CHIP upregulation in this model system was not as pronounced as in the human tissue samples. This observation may be due to the fact that we used neuron-enriched cultures for our OGD experiments, which allow us to better detect neuronal CHIP expression levels as compared to the human tissue samples which include neurons and glia. Due to our concern that we would not be able to fully capture the molecular effects of CHIP upregulation on cell fate, we decided to move into the HT-22 cells that allow us to stably drive CHIP expression at high levels.

The HT-22 neural cells were chosen for our studies because they have been used extensively to model oxidative injury (29, 46). In this model, the addition of extracellular glutamate blocks the glutamate-cystine antiporter in the plasma membrane, leading to the loss of the key intracellular antioxidant GSH. The absence of functional NMDA receptors in these cells makes for a near pure oxidative insult versus a mixed oxidative and excitotoxic insult (29, 30, 46).

Although we initially hypothesized that increasing CHIP would be neuroprotective, we observed quite the opposite in modeling chronic CHIP overexpression using neural cells. Although we did not observe significant alterations in GSH or GSSG levels in our cell lines using HPLC analysis (data not shown), we found that chronic CHIP overexpression was associated with decreased proteasome function, increased protein inclusion formation, increased levels of total oxidized proteins, and poor survival after acute oxidative injury. Increased protein ubiquitination and a loss of proteasome activity have also been reported after ischemic stress in animal models, but they have never been linked to increases in expression levels of CHIP or other E3 ligases (24).

We hypothesize that the mechanism by which chronic CHIP overexpression interferes with protein turnover is linked to either increased substrate generation or decreased substrate turnover. We favor a model in which CHIP overexpression leads to a physiological overload of polyubiquitinated proteins, thereby resulting in decreased substrate cleavage as CHIP-tagged substrates compete with the fluorogenic proteasome substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC for access to the proteasome. Our data further support a model in which CHIP overexpression may fundamentally alter baseline proteasome activity.

This evidence is the first to show that chronic CHIP overexpression proves to be detrimental to cell survival, while the reduction of CHIP levels increases neuronal tolerance to acute oxidative injury. In accordance with our studies investigating the effects of CHIP knockdown on cellular outcome after acute oxidative injury, studies by Casarejos (31) also demonstrate that the knockout of the E3 ligase Parkin may be beneficial for cell survival. While we investigated the effect of glutamate-induced oxidative stress on cell fate, Casarejos' group applied mild proteasomal inhibition. Given that the failure of the proteasome has been implicated in various chronic neurodegenerative diseases (5), studies investigating the effect of Parkin knockout on cell survival after long-term proteasome inhibition would be able to more fully capture the pathologies observed in chronic neurodegenerative diseases. In our model, chronic CHIP overexpression results in decreased baseline proteasome activity, thereby providing a pliable model to examine the effects of long-term proteasome inhibition on cellular survival.

Taken together, this work is the first evidence that CHIP expression levels are elevated in the cerebral cortex of patients after ischemic stroke. Our data support a model whereby chronic CHIP overexpression in neural cells can impair protein turnover and cellular survival after acute oxidative injury. Moreover, by moving to primary neuronal cultures, we found that short-term silencing of CHIP significantly decreases vulnerability to oxidative stress. This suggests that the observed increase in CHIP expression in ischemic stroke may be detrimental to cell survival and that any strategy to develop genetic or small molecule therapies targeting CHIP may indeed have short-term benefits, yet chronic upregulation of CHIP may worsen cellular outcome in the context of acute neurological injury.

Abbreviations Used

- CHIP

C-terminus of HSC70 interacting protein

- DAPi

4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GSH

glutathione

- HIP

HSC70 interacting protein

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HSC70

heat shock cognate 70

- HSP

heat shock protein

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MEM

minimum essential medium

- MG132

Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartic acid

- OGD

oxygen glucose deprivation

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI

propidium iodide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Drs. Cam Patterson and Leonard Petrucelli for helpful discussion and providing reagents, to Mrs. Jacquelynn Brown for the generation and maintenance of primary neuronal cultures, Drs. Gregg Stanwood and Pat Levitt for helpful suggestions, as well as to the members of the McLaughlin lab. Dr. Rashed Nagra generously provided tissue samples from the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center, VA West Los Angeles Healthcare Center, which is sponsored by the NINDS/NIMH, National MS Society, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This work was supported by NIH grants NS050396 (BM), NIEHS ES014668 (JC), the Vanderbilt Neuroscience predoctoral training Fellowship T32 MH064913 (JS), training grant MH065215 (SLHZ), and the Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. Statistical and graphical support was provided by P30HD15052 (Vanderbilt Kennedy Center).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Aizenman E. Stout AK. Hartnett KA. Dineley KE. McLaughlin B. Reynolds IJ. Induction of neuronal apoptosis by thiol oxidation: putative role of intracellular zinc release. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1878–1888. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson LG. Meeker RB. Poulton WE. Huang DY. Brain distribution of carboxy terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) and its nuclear translocation in cultured cortical neurons following heat stress or oxygen-glucose deprivation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;15:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arndt V. Rogon C. Höhfeld J. To be, or not to be–molecular chaperones in protein degradation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2525–2541. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7188-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beere HM. Green DR. Stress management—heat shock protein-70 and the regulation of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berke SJS. Paulson HL. Protein aggregation and the ubiquitin proteasome pathway: gaining the UPPer hand on neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan PH. Reactive oxygen radicals in signaling and damage in the ischemic brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:2–14. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y. Stevens B. Chang J. Milbrandt J. Barres BA. Hell JW. NS21: re-defined and modified supplement B27 for neuronal cultures. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;171:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi DW. Excitotoxic cell death. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coux O. Tanaka K. Goldberg AL. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cyr DM. Hohfeld J. Patterson C. Protein quality control: U-box-containing E3 ubiquitin ligases join the fold. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:368–375. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai Q. Zhang C. Wu Y. McDonough H. Whaley RA. Godfrey V. Li HH. Madamanchi N. Xu W. Neckers L. Cyr D. Patterson C. CHIP activates HSF1 and confers protection against apoptosis and cellular stress. EMBO J. 2003;22:5446–5458. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalle-Donne I. Rossi R. Giustarini D. Milzani A. Colombo R. Protein carbonyl groups as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;329:23–38. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(03)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis JB. Maher P. Protein kinase C activation inhibits glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in a neuronal cell line. Brain Res. 1994;652:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhodda VK. Sailor KA. Bowen KK. Vemuganti R. Putative endogenous mediators of preconditioning-induced ischemic tolerance in rat brain identified by genomic and proteomic analysis. J Neurochem. 2004;89:73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickey CA. Patterson C. Dickson D. Petrucelli L. Brain CHIP: removing the culprits in neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirnagl U. Becker K. Meisel A. Preconditioning and tolerance against cerebral ischaemia: from experimental strategies to clinical use. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:398–412. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du S. McLaughlin B. Pal S. Aizenman E. In vitro neurotoxicity of methylisothiazolinone, a commonly used industrial and household biocide, proceeds via a zinc and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7408–7416. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07408.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giffard RG. Xu L. Zhao H. Carrico W. Ouyang Y. Qiao Y. Sapolsky R. Steinberg G. Hu B. Yenari MA. Chaperones, protein aggregation, and brain protection from hypoxic/ischemic injury. J Exp Biol. 2004;207((Pt 18)):3213–3220. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginsberg MD. Neuroprotection for ischemic stroke: past, present and future. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:363–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Zulueta M. Feldman AB. Klesse LJ. Kalb RG. Dillman JF. Parada LF. Dawson TM. Dawson VL. Requirement for nitric oxide activation of p21(ras)/extracellular regulated kinase in neuronal ischemic preconditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:436–441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hohfeld J. Cyr DM. Patterson C. From the cradle to the grave: molecular chaperones that may choose between folding and degradation. EMBO Rep. 2001;10:885–890. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imai Y. Soda M. Hatakeyama S. Akagi T. Hashikawa T. Nakayama K-I. Takahashi R. CHIP is associated with Parkin, a gene responsible for familial Parkinson's disease, and enhances its ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol Cell. 2002;10:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller JN. Huang FF. Zhu H. Yu J. Ho YS. Kindy MS. Oxidative stress-associated impairment of proteasome activity during ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiang JG. Tsokos GC. Heat shock protein 70 kDa: molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;80:183–201. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labiche LA. Grotta JC. Clinical trials for cytoprotection in stroke. NeuroRx. 2004;1:46–70. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legos JJ. McLaughlin B. Skaper SD. Strijbos PJLM. Parsons AA. Aizenman E. Herin GA. Barone FC. Erhardt JA. The selective p38 inhibitor SB-239063 protects primary neurons from mild to moderate excitotoxic injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;447:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01890-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo Y. DeFranco DB. Opposing roles for ERK1/2 in neuronal oxidative toxicity: distinct mechanism of ERK1/2 action at early versus late phases of oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16436–16442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maher P. The effects of stress and aging on glutathione metabolism. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:288–314. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maria JC. Rosa MS. José AR-N. Ana G. Juan P. Jose GC. Justo García de Y. Maria AM. Parkin deficiency increases the resistance of midbrain neurons and glia to mild proteasome inhibition: the role of autophagy and glutathione homeostasis. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1523–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin BA. Hartnett KA. Erhardt JA. Legos JJ. White RF. Barone FC. Aizenman E. Caspase 3 activation is essential for neuroprotection in preconditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0232966100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLaughlin BA. Pal S. Tran MP. Parsons AA. Barone FC. Erhardt JA. Aizenman E. p38 activation is required upstream of potassium current enhancement and caspase cleavage in thiol oxidant-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3303–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03303.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLaughlin BA. Nelson D. Erecinska M. Chesselet MF. Toxicity of dopamine to striatal neurons in vitro and potentiation of cell death by a mitochondrial inhibitor. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2406–2415. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin BA. Nelson D. Silver IA. Erecinska M. Chesselet M-F. Methylmalonate toxicity in primary neuronal cultures. Neuroscience. 1998;86:279–290. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNamara D. Dingledine R. Dual effect of glycine on NMDA-induced neurotoxicity in rat cortical cultures. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3970–3976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03970.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta SL. Manhas N. Raghubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54:34–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musiek ES. Breeding RS. Milne GL. Zanoni G. Morrow JD. McLaughlin B. Cyclopentenone isoprostanes are novel bioactive products of lipid oxidation which enhance neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1301–1313. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrucelli L. Dawson TM. Mechanism of neurodegenerative disease: role of the ubiquitin proteasome system. Ann Med. 2004;36:315–320. doi: 10.1080/07853890410031948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pratt WB. Morishima Y. Peng H-M. Osawa Y. Proposal for a role of the Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery in making triage decisions when proteins undergo oxidative and toxic damage. Exp Biol Med. 2010;235:278–289. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian S-B. McDonough H. Boellmann F. Cyr DM. Patterson C. CHIP-mediated stress recovery by sequential ubiquitination of substrates and Hsp70. Nature. 2006;440:551. doi: 10.1038/nature04600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosamond W. Flegal K. Furie K. Go A. Greenlund K. Haase N. Hailpern SM. Ho M. Howard V. Kissela B. Kittner S. Lloyd-Jones D. McDermott M. Meigs J. Moy C. Nichol G. O'Donnell C. Roger V. Sorlie P. Steinberger J. Thom T. Wilson M. Hong Y the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosser MFN. Washburn E. Muchowski PJ. Patterson C. Cyr DM. Chaperone Functions of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase CHIP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22267–22277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahara N. Murayama M. Mizoroki T. Urushitani M. Imai Y. Takahashi R. Murata S. Tanaka K. Takashima A. In vivo evidence of CHIP up-regulation attenuating tau aggregation. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1254–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharp FR. Massa SM. Swanson RA. Heat-shock protein protection. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:97–99. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Leyen K. Siddiq A. Ratan RR. Lo EH. Proteasome inhibition protects HT22 neuronal cells from oxidative glutamate toxicity. J Neurochem. 2005;92:824–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Engelhardt J. Coserea I. Pawlak V. Fuchs EC. Köhr G. Seeburg PH. Monyer H. Excitotoxicity in vitro by NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L. Chen Y. Sternberg P. Cai J. Essential roles of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway in regulating Nrf2-dependent antioxidant functions in the RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1671–1678. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X. Defranco DB. Alternative effects of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway on glucocorticoid receptor down-regulation and transactivation are mediated by CHIP, an E3 ligase. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1474–1482. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yenari MA. Heat shock proteins and neuroprotection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;513:281–299. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0123-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang C. Xu Z. He X-R. Michael LH. Patterson C. CHIP, a cochaperone/ubiquitin ligase that regulates protein quality control, is required for maximal cardioprotection after myocardial infarction in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2836–H2842. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01122.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang F. Liu CL. Hu BR. Irreversible aggregation of protein synthesis machinery after focal brain ischemia. J Neurochem. 2006;98:102–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]