Abstract

Background

Psychiatric emergencies such as acute psychomotor agitation or suicidality often arise in non-psychiatric settings such as general hospitals, emergency services, or doctors’ offices and give rise to stress for all persons involved. They may be life-threatening and must therefore be treated at once. In this article, we discuss the main presenting features, differential diagnoses, and treatment options for the main types of psychiatric emergency, as an aid to their rapid and effective management.

Method

Selective literature review.

Results and conclusion

The frequency of psychiatric emergencies in non-psychiatric settings, such as general hospitals and doctors’ offices, and their treatment are poorly documented by the few controlled studies and sparse reliable data that are now available. The existing evidence suggests that the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric emergencies need improvement. The treatment of such cases places high demands on the physician’s personality and conduct, aside from requiring relevant medical expertise. Essential components of successful treatment include the establishment of a stable, trusting relationship with the patient and the ability to “talk down” agitated patients calmly and patiently. A rapid and unambiguous decision about treatment, including consideration of the available options for effective pharmacotherapy, usually swiftly improves the acute manifestations.

Psychiatric emergencies are often, but not always, caused by mental illness. They require action without delay to save the patient and other persons from mortal danger or other serious consequences (1). Immediate treatment directed against the acute manifestations is needed, both to improve the patient’s subjective symptoms and to prevent behavior that could harm the patient or others.

Learning objectives

The learning objectives for readers of this article are:

to gain an overview of the major types of psychiatric emergency;

to know the legal basis (in Germany) for the prevention of harm to the patient and other persons, and to be able to apply it;

to become acquainted with the differential diagnosis of psychiatric emergencies and with effective strategies for treating them.

There are hardly any reliable data on the frequency of psychiatric emergencies in general and family practice, in the emergency rooms of general hospitals, or among the cases that are dealt with by emergency medical teams. In various studies, the prevalence rate of psychiatric emergencies has been estimated at anywhere from 10% to 60% (2). This rather wide variation may well reflect multiple inadequacies of method. Considering the current realities in the organization of medical care, as well as the public’s general aversion to mental disturbances of any kind, we should not be surprised that the initial care of psychiatric emergencies usually does not take place in specialized psychiatric institutions. Mentally ill persons who do not want to be stigmatized mainly tend to visit the emergency rooms of general hospitals, which are usually both easy to get to and open around the clock.

Prevalence.

The prevalence rate of psychiatric emergencies in non-psychiatric institutions such as general hospitals and general medical practices has been estimated at anywhere from 10% to 60%.

According to a retrospective study performed at the Hannover Medical School (Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, MHH), the rate of presentation of psychiatric patients to the emergency room in the year 2002 was 12.9% (3). 12% to 25% of emergency cases seen by the emergency medical services were psychiatric emergencies (4, 5). General practitioners and family physicians, who are the most broadly accepted providers of primary care, saw psychiatric emergencies in 10% of cases. Be this as it may, there are hardly any reliable data on this matter from the German-speaking countries, and differences in health care systems from one country to another may limit the generalizability of findings from any particular country (6, 7).

It follows from the above that all physicians need basic knowledge of the diagnostic and therapeutic steps to be taken in psychiatric emergencies. The same conclusion can be drawn from a number of studies in which it was found that as many as 60% of mental disturbances presenting to medical attention in primarily non-psychiatric facilities and hospitals are neither correctly diagnosed nor properly treated (2, 8).

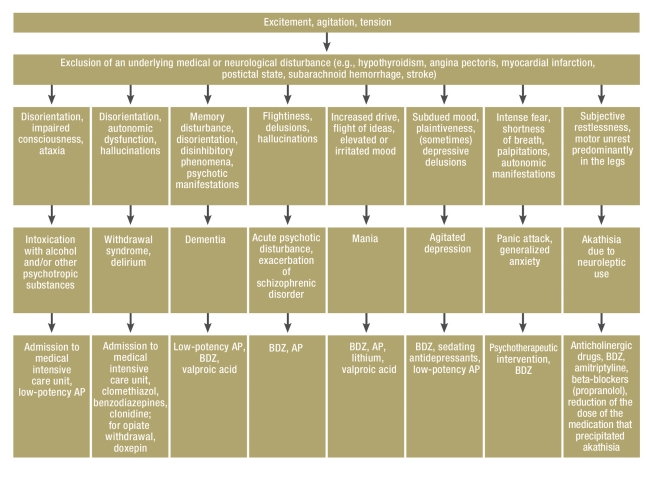

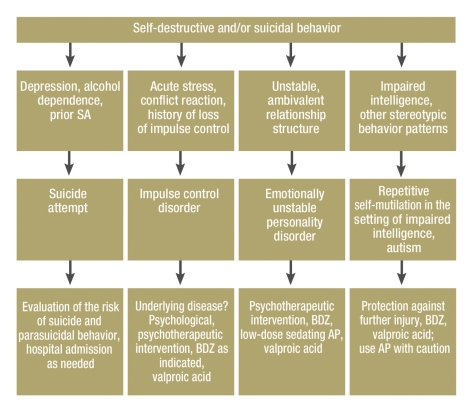

The two main types of psychiatric emergency are: (1) acute excitement with psychomotor agitation and (2) self-destructive or suicidal behavior. The goal of this article is to present the diagnostic and differential diagnostic aspects of these entities and to indicate how they can be treated. The algorithms shown in Figures 1 and 2 are intended as aids to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making; this is not to say that they must be rigorously followed in every case. In view of the lack of high-grade evidence in emergency psychiatry, the algorithms and treatment recommendations given here should be regarded as expert advice, rather than certain knowledge. They are based on the authors’ clinical experience, and they correspond to the current management of psychiatric emergencies in the Psychiatry Department at the University of Bochum (Germany). Every physician should, however, be familiar with the basic aspects of management of psychiatric emergencies that are covered in the next section.

Figure 1.

The differential diagnosis and acute treatment of psychomotor excitement and agitation AP, antipsychotic drugs; BDZ, benzodiazepines

Figure 2.

Differential diagnosis and acute treatment of self-destructive and suicidal behavior

AP, antibiotic drugs; BDZ, benzodiazepines; SA, suicide attempt

Current data.

There are hardly any reliable data on the frequency of psychiatric emergencies in the German-speaking countries, because only a few controlled studies have been performed and health care systems differ from one country to another.

The legal basis in Germany.

Paragraph 34 StGB, the law concerning mentally ill persons (PsychKG), and the law on guardianship are the legal basis for decisions that must be taken to prevent harm to the patient or others.

Basic aspects of management of psychiatric emergencies

Physicians who are not psychiatrists should nevertheless have basic knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric emergencies, as well as the legal basis (depending on the the jurisdiction in which they practice) for the treatment of the mentally ill. This is important, because acutely mentally ill persons often have limited insight into their illness and limited ability to cooperate with their treatment, and measures will sometimes need to be taken that restrict their personal freedom. In Germany, a major source of legal guidance in these matters is the law on mentally ill persons (“Psychisch-Kranken-Gesetz,” PsychKG). This law varies to some extent from one German federal state to another; it states that any physician—perhaps with the involvement and mediation of the Social Psychiatry Service—can petition the responsible court to commit a person with a mental disturbance to a psychiatric hospital because of an acute danger to this person or other persons, in order to avert harm. In some circumstances, help can be officially requested and obtained from the police and/or the fire department, if necessary (Box 1).

Box 1. The legal basis for intervention in psychiatric emergencies in Germany.

-

When there is a justifying emergency (Paragraph 34 StGB), medically indicated treatment measures may be taken

to prevent danger in an emergency

even when the patient lacks the capacity to consent

-

PsychKG (“Psychisch-Kranken-Gesetz,” the German law concerning mentally ill persons)

regulates the modalities of accommodation for the mentally ill (“involuntary commitment”)

varies from one federal state to another

Any physician or citizen can initiate judicial commitment proceedings in case of danger to a mentally ill person or to others.

Commitment is by the decision of a judge.

-

BtG (“Betreuungsgesetz,” the German law on guardianship)

If the patient is unable to take care of his or her own affairs because of illness, a guardianship can be established; once a guardianship has been established, the guardian can be consulted.

Petitions for guardianship can be submitted to the appropriate court and are usually decided on the basis of an expert medical (psychiatric) evaluation.

Guardianship can be only for a limited time, or with a restriction to certain areas (e.g., health care, place of residence).

modified from (9)

Initial contact.

Physicians making the initial contact with acutely mentally ill persons should show goal-orientation, rationality, and empathy. This is an important first step toward effective treatment.

Psychomotor agitation.

Psychomotor excitement and agitation can reflect many different underlying conditions, ranging from organic disease to a variety of mental illnesses.

In an emergency situation, the physician must establish conversational contact with the patient and take the history more rapidly and in more structured fashion than in a non-emergency psychiatric or medical interview, both because of the intensity of the patient’s disease state and because of the possible danger to the patient or others (9). Along with noting the patient’s main subjective complaints, the examiner must observe the patient’s behavior closely while examining him or her, paying attention to spontaneous movements and any signs of psychomotor agitation, tension, or impulsiveness. If persons other than the patient can supply any further history, the examiner should ask them specifically about the patient’s behavior or abnormalities of any other kind before the emergency situation arose.

The setting for the initial examination should be chosen to maximize the safety of the patient and the examiner (10– 12). Laying down clear structures, including telling the patient what type of behavior is expected of him or her, is a more sensible and probably more successful approach than simply applying restrictive measures without any critical thought behind them. Firmness, goal-orientation, rationality, and empathy are very important when one is dealing with acutely mentally ill persons, and this basic attitude should be communicated to the patient both verbally and non-verbally through the examiner’s behavior. The establishment of a personal approach to a highly excited patient, or to a fearful and suicidal one, through a friendly, empathetic, respectful, and understanding attitude is a vital component of the initial treatment and opens the way to the therapeutic steps that will be taken afterward (9, 11).

Before any treatment is initiated, organic disease should be ruled out, if possible. Thus, a thorough general medical and neurological examination is indispensable. Particularly when the diagnosis is unclear, further diagnostic tests such as cranial computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and relevant laboratory studies, should be performed without delay. Pharmacotherapy should be begun only if situational calming and confidence-building measures have been tried without success. The choice of medication and of its route of administration depends on the patient’s diagnosis and on the particular disease manifestations that are to be treated. Specific recommendations for optimal treatment can be found, for example, in the S2 guideline of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Neurology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde, DGPPN), which is entitled “Therapeutische Maßnahmen bei aggressivem Verhalten in der Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie” (therapeutic measures for aggressive behavior in psychiatry and psychotherapy).

Differential diagnostic considerations.

If possible, diagnostic tests to narrow down the differential diagnosis should be performed right away.

Psychomotor excitement and agitation

Diagnostic evaluation

Psychomotor excitement and agitation can reflect many different underlying conditions, ranging from organic disease to a variety of mental illnesses (12) (Figure 1).

Protect yourself first.

Trained nurses or other staff should be present on first contact with an aggressive, tense patient. Patients’ behavior in emergencies is unpredictable, nor is their strength easy to assess; the examiner’s first duty is to see to his or her own safety.

Depending on the patient’s baseline affective state and on the severity of the acute disturbance, psychomotor agitation can manifest itself as mild agitation with an anxious quality or as more severe conditions ranging to a highly excited state with marked aggressiveness. The following organic conditions can cause an excited state:

Talking down.

The treatment of acute states of excitement and agitation includes “talking down” and the use of sedating medications such as benzodiazepine or sedating antipsychotic drugs.

dementing diseases

medical illnesses such as hyperthyroidism or myocardial infarction

neurological disturbances such as encephalitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or postictal state.

Excited states in the setting of dementing diseases are usually associated with spatial and temporal disorientation, and commonly also with abnormal behavior. The possibility of an underlying medical illness should be ruled out (or confirmed) by a thorough diagnostic evaluation of the potential organic causes. Acute neurological disturbances of brain function usually impair consciousness; in some cases, such disturbances are hard to tell apart from intoxication with a psychotropic substance. Patients in an impulsive and hostile excited state need, above all, to be monitored in an intensive care setting while measures are taken to protect them from harming themselves or behaving aggressively toward others.

Suicidality.

Suicidality and self-destructive behavior account for up to 15% of psychiatric emergencies. Evaluating these conditions correctly is a challenging matter.

Therapeutic measures

The main objective in treating acute states of excitation and agitation is to keep the patient from inflicting harm on him- or herself and others. This is generally accomplished with pharmacotherapy (most often by sedation), which must not, however, be allowed to stand in the way of a further differential-diagnostic evaluation (13). “Talking down” is often successful: this is the attempt to calm the patient verbally by speaking with him or her in a friendly way, in an even tone, and maintaining conversational contact (1). An excited state may wear off over a short period of time only to come back rapidly and become even more severe than before (“the calm before the storm”), giving a misleading picture of the actual danger. One should, therfore, always try to have trained nurses or other auxiliary staff in the room during the initial contact with an aggressive, tense patient. Dealing with the patient too energetically may only increase his or her aggressiveness, and one should beware of overestimating oneself, as patients in excited states can muster great strength. In such cases, the examiner’s first duty is to see to his or her own safety.

Excited states with an anxious coloration in patients taking stimulants and hallucinogenic drugs are best treated with benzodiazepines (14) (Figure 1). In agitation due to withdrawal of alcohol, opioids, or sleeping medication, clomethiazol p.o. is the medication of first choice to prevent delirium, or to treat delirium that is already present; clonidine or a beta-blocker can be added to treat any accompanying autonomic manifestations, while an antipsychotic can be added to treat psychosis. Another way to treat alcohol withdrawal syndrome, particularly when it presents with seizures, is with a benzodiazepine, such as diazepam or lorazepam. Opioid withdrawal syndrome is treated instead with a sedating antidepressant, such as doxepin. When taking patients off benzodiazepines, one should take care not to lower the dose too quickly. Psychomotor excitement with aggressive behavior as a component of schizophrenic psychosis, a problem often necessitating police intervention (15), can be treated effectively with antipsychotic drugs (16) Box 2).

Box 2. Pharmacotherapy of a psychotic excited state.

Levomepromazine: 50 mg i.m. or 100 mg p.o. Possible acute adverse effects: hypotension, tachycardia, syncope

Haloperidol: 5–15 mg i.m. or i.v. Possible acute adverse effect: dyskinesia

Diazepam: 5–10 mg i.v.; highest daily dose, 40–60 mg; inject slowly, as it may depress respiration; lorazepam 2 mg

Zuclopenthixol: 100–200 mg i.m. as a short-term depot neuroleptic drug (acute schizophrenic psychoses, mania)

Olanzapin: 5–20 mg as an orodispersible tablet or i.m.

Risperidone: 2–4 mg as an orodispersible tablet

modified from (10)

Psychomotor excitement and agitation are also typical features of agitated depression, although, in this condition, the depressive mood is usually obvious, pointing the way to the correct diagnosis. In agitated depression, as in other types of depression, antidepressants take effect only after a delay; thus, a benzodiazepine or low-potency antipsychotic drug should be added on at once, to provide immediate relief. Excited states caused by panic attacks are best treated with benzodiazepines, if pharmacotherapy is the treatment chosen. States of excitement and agitation can be seen in acute stress reactions, too, or as a manifestation of diseases from the anxiety disorder spectrum; benzodiazepines are indicated in such cases as well, but they should be replaced as soon as possible with targeted psychotherapy because of the potential for abuse.

Hospitalization.

Patients who have attempted suicide, have complex psychosocial stress factors, are difficult to evaluate, and are not capable of reaching an agreement with a physician should be treated in the hospital, even against their will if necessary.

It should not be forgotten that a state of agitation can also be caused by antipsychotic or other dopaminergic medication, e.g., by metoclopramide. This type of agitation, called akathisia, is characterized by restless movements of (mainly) the legs when the patient either sits or stands, often accompanied by a distressing feeling of unrest. If akathisia is misinterpreted as a psychotic manifestation, a vicious circle can arise in which akathisia leads to an increase in the antipsychotic dose, leading to yet more akathisia. The first-line treatment of acute akathisia is with anticholinergic drugs, benzodiazepines, amitriptyline, or the beta-blocker propranolol. Moreover, the antipsychotic drug that induced akathisia should be changed, or its dose lowered.

Self-destructive and suicidal behavior

Diagnostic evaluation

Suicidality and self-destructive behavior account for up to 15% of psychiatric emergencies (3, 15, 17). In this connection, the physician may face the very difficult task of gauging the risk of suicide in a patient who has already attempted suicide or who currently has suicidal ideation. The phases classically described by Pöldinger (18) and the pre-suicidal syndrome described by Ringel (19) are not always floridly present (17). In general, the suicide rate rises with advancing age (20). Further factors associated with an elevated risk of suicide include the following:

prior suicide attempts

alcohol and drug dependency

the loss of important persons in the patient’s life

long depressive episodes

prior psychiatric treatment

physical illness

unemployment or retirement

rejection of offers of help

a history of violent behavior.

About 98% of persons who commit suicide are either mentally or physically ill. Elderly men living alone are more likely to commit suicide than elderly women living alone. Living in a city, rather than the country, is a further risk. Suicide is also more common in the spring and summer than in the autumn and winter. Many suicide attempts are never detected as such: in Germany, where about 12 500 people commit suicide every year, the number of suicide attempts is estimated to be between 5 and 30 times higher than this. 80% of persons who commit suicide have previously stated their intention to do so—often, for example, to their family physician, through a remark such as “I can’t see any meaning to it all any more,” or the like. 30% to 40 % of suicide victims attempted suicide at least once beforehand (9, 17) (Box 3).

Box 3. Risk factors for suicidality.

-

Mental illness

depression, addiction, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder

-

Prior suicidality

expressions of suicidal intent

prior suicide attempts (especially in the recent past)

-

In older persons:

loneliness, widowhood/widowerhood

painful chronic disease impairing quality of life

-

In younger persons:

developmental and relationship difficulties

problems in the family, school, or job training

problems with illicit drugs

-

Traumatic experiences

loss of a partner, severely hurt feelings

loss of social, cultural, or political context

identity crises, disturbances of adaptation

long-term joblessness, lack of prospects

criminality, traffic offenses (with injury or mortal harm to another person)

Physical illness severely impairing quality of life

modified from (17)

It is often difficult to decide whether inpatient treatment is needed or outpatient treatment suffices. Reasons for hospital admission include

The main steps of treatment.

Creation of a doctor-patient relationship that the patient experiences as helpful and durable

Use of sedating medications such as benzodiazepines, antipsychotic drugs, and sedating antidepressants

a lack of social connections,

a history of impulsive behavior,

concrete plans for a suicidal act, or parasuicidal behavior.

In an emergency situation, it is often hard to tell at first whether the apparent suicide attempt was more a cry for help or an actual aggressive act against the self with the serious intention of committing suicide.

Therapeutic measures

In every case of self-destructive behavior or attempted suicide, emergency management should include the provision of immediate medical care (diagnosis and treatment of the underlying psychiatric disturbance), the elucidation of existing acute conflicts, and an attempt to establish a therapeutic bond that the patient experiences as helpful and durable, through the use of concrete agreements. The patient should be told about the possibility of, and perhaps the need for, an examination by a psychiatrist, and should be prepared for this examination. Particular caution is needed if the patient is uncooperative, refuses to accept help, trivializes the danger of the suicide attempt, or manifests an abrupt change to a highly relaxed or even euphoric mood. If suicidality persists, and no reliable agreement with the patient can be reached, then the patient must be admitted to a protected psychiatric ward for close observation and surveillance. Thus, in some cases, involuntary commitment in accordance with the law cannot be avoided. Self-destructive behavior (which may be repetitive) is not the same thing as suicidal or parasuicidal behavior; it is seen, for example, in patients with personality disorders, who, of course, are also at elevated risk of suicide attempts and suicide. Self-mutilating behavior with motor stereotypies of a self-damaging type is more commonly seen among intellectually impaired and autistic persons. Severe self-mutilation necessitates inpatient psychiatric crisis intervention and, possibly, physical restraint.

Prerequisites.

Psychiatric emergencies require rational care in a setting of interdisciplinary collaboration. It should be delivered with empathy and without overestimating one’s own capabilities as a physician.

In the acutely suicidal phase, sedating medications, such as benzodiazepines, sedating antidepressants, and low-potency antipsychotic drugs, can be very helpful (Figure 2). The main immediate goal is the symptomatic treatment of anxiety with rapid restoration of calm. Lorazepam has been found to be particularly suitable and is now well established for this indication. The prescribing physician should make sure that the patient is not storing up the prescribed medication for another suicide attempt; thus, it is reasonable for the medication to be given under close medical supervision for a period of up to several days. Self-destructive behavior in intellectually impaired persons generally takes the form of jactations (rhythmic back-and-forth movements of the body), or of biting of the lips, hands, and arms; on the other hand, persons who are emotionally unstable or who have an emotionally unstable personality disorder of borderline type or an impulse-control disorder often present with recurrent self-inflicted cutting injuries. Most of these patients have a decreased sensitivity to pain. Repetitive self-injury in such cases is usually due to conflicts with the patient’s social environment; because of a low tolerance for frustration, the patient responds to these conflicts with severely hurt feelings or the desire to lower inner tension. It is especially difficult for the physician to establish robust contact with such patients in the setting of a psychiatric emergency, just as it is with suicidal patients in general; serious mistakes can be made (21) (Box 4).

Box 4. Common errors in the care of suicidal patients.

Failure to take expressed suicidal intent seriously

Failure to diagnose a mental illness

Delay or omission of hospitalization

Misinterpreting the patient’s tendency to minimize

Inadequate exploration of the current and (possibly) prior circumstances leading to suicidality

Inadequate attention to the history supplied by persons other than the patient

Excessively rapid search for opportunities for positive change

Overestimating one’s own therapeutic capabilities (the doctor’s or therapist’s feeling of omnipotence)

Misinterpretation of calmness in the period between the decision to commit suicide and the planned suicide

Non-comprehensive and non-binding treatment recommendations

modified from (17)

All suicidal patients and all patients who have attempted suicide should undergo psychotherapy and rehabilitation, either individually or in group therapy (22).

Reasons to hospitalize patients with psychiatric emergencies include.

lack of social contacts

history of impulsive behavior

concrete plans for a suicidal act, or parasuicidal behavior

Further information on CME.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education.

Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquiredonly through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire within 6 weeks of publication of the article. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit“uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

The solutions to the following questions will be published in issue 21/2011. The CME unit “Central Venous Port Systems as an Integral Part of Chemotherapy” (issue 9/2011) can be accessed until 15 April 2011.

For issue 17/2011, we plan to offer the topic “Hearing Impairment.”

Solutions to the CME questionnaire in issue 5/2011:

Delank K-S, Wendtner C, Eich HT, Eysel P:

The Treatment of Spinal Metastases.

Solutions: 1b, 2d, 3c, 4e, 5b, 6e, 7c, 8d, 9c, 10a

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

What percentage of psychiatric emergencies in institutions that are not primarily psychiatric fail to be recognized and appropriately treated?

up to 20%

up to 40%

up to 60%

up to 80%

up to 100%

Question 2

What does the abbreviation PsychKG stand for?

a kind of physical therapy with psychological approach

the psychotherapeutic patient interview

the German law concerning mentally ill persons

the Psychiatric Cooperative Group in Germany

the German law concerning psychiatric patients

Question 3

What portion of German mental health law provides the legal basis for the prevention of injury to a mentally ill person, or to other persons, in cases of psychiatric emergency?

Paragraph 34 StGB, PsychKG, BtG

Paragraph 203 and Paragraph 227 BGB

Article 2 GG and BtG

PsychKG and Paragraph 249 BGB

Paragraph 230 StGB and Article 104 GG

Question 4

Which of the following medications is least suitable for the treatment of an excited, agitated patient?

diazepam

zuclopenthixol

haloperidol

sertraline

levomepromazine

Question 5

What is the therapeutic goal of “talking down”?

to calm the patient verbally

to relax the patient with meditation exercises

to discuss the patient’s state of tension with the patient

to calm the patient through physical contact

to converse quietly with the patient

Question 6

Which of the following is associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide?

a steady job

brief episodes of melancholy

a steady relationship

physical illness

a large circle of friends

Question 7

A depressed patient with known alcohol dependence is brought to the psychiatric emergency room. She tried to commit suicide once before and has now been found attempting suicide again. What initial therapeutic steps should now be taken acutely?

extensive medical history and accompanying behavioral therapy

outpatient psychotherapy and prescription of a low-dose antipsychotic drug

outpatient gestalt therapy and prescription of a benzodiazepine and valproate

psychological and psychotherapeutic intervention, along with the administration of benzodiazepine and valproate as needed

determination of the risk of suicide and parasuicidal behavior, and admission to the hospital as needed

Question 8

Which of the following is a common error in dealing with suicidal patients?

including the patient’s spouse or partner in the treatment

delivering psychotherapy in a group-therapy setting

misinterpreting the patient’s tendency to trivialize

rapidly organizing admission to an inpatient facility

showing empathy while speaking with the patient

Question 9

Which of the following is a sedating antidepressant used to treat opioid withdrawal syndrome in the psychiatric emergency setting?

alfentanil

pipamperone

valproic acid

lithium

doxepin

Question 10

Which of the following are rare presentations of psychiatric emergencies?

visual hallucinations, illusory misidentifications, suggestibility, and fidgeting

cognitive disturbances and intermittent disorientation

dermatozoal delusion and obsessive-compulsive manifestations

psychomotor excitation and agitation or self-destructive or suicidal behavior

depression

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Rössler W, Riecher-Rössler A. Hewer W, Rössler W, editors. Versorgungsebenen in der Notfallpsychiatrie Das Notfall Psychiatrie Buch. Urban & Schwarzenberg. 2002:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arold V. Das Problem der Diagnostik psychischer Störungen in der Primärversorgung. In: Arold V, Diefenbacher A, editors. Psychiatrie in der klinischen Medizin. Darmstadt: Steinkopf; 2004. pp. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kropp S, Andreis C, Wildt B, Sieberer M, Ziegenbein M, Huber TJ. Characteristics of psychiatric patients in the accident and emergency department. Psychiat Prax. 2007;34:72–75. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pajonk FG, Schmitt P, Biedler A, et al. Psychiatric emergencies in prehospital emergency medical systems: a prospective comparison of two urban settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pajonk FG, D Amelio R. Psychosocial emergencies-agitation, aggression and violence in emergency and search and rescue services. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2008;43:514–521. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1083093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li PL, Jones I, Richards J. The collection of general practice data for psychiatric service contracts. J Public Health Med. 1994;16:87–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson AE, Emmerson WB, Frost AD, Powell JL. “GP Psych Opinion”: evaluation of a psychiatric consultation service. Med J Aust. 2005;183:87–90. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herzog T, Stein B. Ungenügende Identifizierung und Berücksichtigung psychischer Störungen Konsiliar- und Liaisonpsychosomatik und -psychiatrie. In: Herzog T, Stein B, Söllner W, Franz M, editors. Stuttgart, New York: Schattauer; 2003. pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berzewski H. Allgemeine Gesichtspunkte Der psychiatrische Notfall. In: Berzewski H, editor. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neu P. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 2008. Akutpsychiatrie. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abderhalden C, Nedham I, Dassen T, Haifens R, Haug HJ, Fischer JE. Structured risk assessment and violence in acute psychiatric wards: randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:44–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guedj M. Emergency situations in psychiatry. Rev Prat. 2003;53:1180–1185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdos BZ, Hughes DH. Emergency psychiatry: a review of assaults by patients against staff at psychiatric emergency centers. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1175–1177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zealberg JJ, Brady KT. Substance abuse and emergency psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22:803–817. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fähndrich E, Neumann M. The police in psychiatric daily routine. Psychiatr Prax. 1999;26:242–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas P, Alptekin K, Gheorghe M, Mauri M, Olivares JM, Riedel M. Management of patients presenting with acute psychotic episodes of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:193–212. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfersdorf M. Therapie der Suizidalität. In: Möller HJ, editor. Therapie psychischer Erkrankungen. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme; 2006. pp. 1144–1163. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pöldinger W. Erkennung und Beurteilung von Suizidalität. In: Reimer C, editor. Suizid: Ergebnisse und Therapie. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1982. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ringel E. Düsseldorf: Maudrich; 1953. Der Selbstmord. Abschluß einer krankhaften psychischen Entwicklung. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Althaus D, Hegerl U. Ursachen, Diagnose und Behandlung von Suizidalität. Nervenarzt. 2004;75:1123–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00115-004-1824-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dick B, Sitter H, Blau E, Lind N, Wege-Heuser E, Kopp I. Behandlungspfade in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. Nervenarzt. 2006;77:14–18. doi: 10.1007/s00115-005-1916-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronisch T. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme; 2002. Psychotherapie von Suizidalität. [Google Scholar]