Abstract

Objective

To compare the medical severity of adolescents with eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS) to those with anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN).

Patients and Methods

Medical records of 1310 females aged 8 through 19 years treated for AN, BN, or EDNOS were retrospectively reviewed. EDNOS patients were subdivided into partial anorexia (pAN) and partial bulimia (pBN) categories if they met all but one DSM-IV criterion for AN or BN, respectively. Primary outcome variables were heart rate, systolic blood pressure, temperature, and QTc interval on electrocardiogram. Additional physiologically significant medical complications were also reviewed.

Results

25.2% had AN, 12.4% BN, and 62.4% had EDNOS. The medical severity of EDNOS patients was intermediate to that of subjects with AN and BN in all primary outcomes. Patients with pAN had significantly higher heart rates, systolic blood pressures, and temperatures than those with AN; patients with pBN did not differ significantly from those with BN in any primary outcome variable; however, subjects with pAN and pBN differed significantly from each other in all outcome variables. Patients with pBN and BN had longer QTc intervals and higher rates of additional medical complications reported at presentation than other groups.

Conclusions

EDNOS is a medically heterogeneous category with serious physiologic sequelae in children and adolescents. Broadening AN and BN criteria in pediatric patients to include pAN and pBN patients may prove to be clinically useful.

Keywords: Children and Adolescents, Adolescent Medicine, Eating Disorders, Child Psychiatry

Introduction

According to current diagnostic criteria, most pediatric patients with disordered eating are diagnosed with eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS), defined in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) as “disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for any specific Eating Disorder,”[1] a categorization that has long troubled practitioners.[2–9] While a handful of studies have examined bone density, fracture rates, or electrocardiograms in EDNOS patients[10–12], most studies on medical sequelae of disordered eating have focused on bulimia nervosa (BN) or anorexia nervosa (AN), and little work has documented the severity, frequency, or clinical significance of EDNOS in young people.[4, 8, 13–15]

Recent studies of EDNOS patients have focused on psychiatric features, comparing adult patients with partial AN (pAN) or partial BN (pBN) to patients meeting full DSM-IV criteria. Patients with pAN and pBN typically have similar psychological profiles to those meeting full criteria for AN and BN, while pAN and pBN differ significantly from each other despite both being subgroups of EDNOS. [4, 16–30]

Numerous medical organizations including the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that patients with severe malnutrition, bradycardia, hypotension, hypothermia, and orthostasis are critically ill and require hospitalization.[31–32] No study has examined how DSM-IV diagnostic criteria correlate with medical severity, and there are no data to validate the commonly held tenet that EDNOS is associated with lower medical severity.

This paper will review current diagnostic criteria and discuss their utility in predicting the medical severity of patients with eating disorders (EDs). Our goal is to describe a large group of pediatric EDNOS patients and compare them to pediatric AN and BN patients. In addition, we will compare the medical severity of EDNOS adolescents with pAN or pBN to those meeting full diagnostic criteria. We predicted that those with EDNOS and pAN or pBN would be less medically compromised than those with full DSM-IV syndromes. Furthermore, we predicted that pAN and pBN would differ significantly from one other with respect to meeting hospitalization criteria.

Patients and Methods

Subjects

All 1310 female patients aged 8–19 years diagnosed with AN, BN, or EDNOS in an academic pediatric ED program from January 1997 through April 2008 were identified. All subjects were initially clinically diagnosed by a board-certified psychiatrist or psychologist with expertise in the assessment of children and adolescents with ED, after diagnostic interviews with both patients and parents or guardians, and as part of a comprehensive evaluation by a multidisciplinary team. Both inpatients and outpatients were included. Because of small within-gender cell sizes that prevented adequate assessment of potential gender differences, male patients were excluded from analyses, as were patients found not to have a DSM-IV diagnosable ED during their evaluation or treatment. A waiver of informed consent and a HIPAA-compliant waiver of individual authorization were granted; all data collection protocols were approved by our Panel on Medical Research in Human Subjects and compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

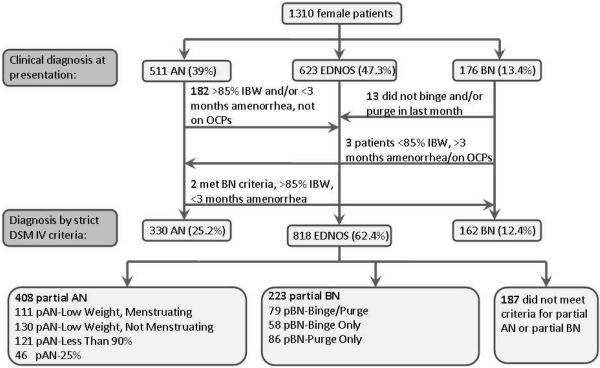

DSM-IV criteria for EDs are guidelines, and allow for latitude in their application in clinical settings. However, this study was designed to answer a primary research question of how DSM-IV diagnostic criteria predict medical outcomes; hence, a systematic retrospective review of all medical records was conducted by two independent assessors and reviewed by the primary investigator, to note relevant clinical parameters at presentation. When indicated after this comprehensive review, patients were recategorized from their original clinical ED diagnosis, using strict DSM-IV criteria (Figure 1). In premenarchal females, AN was diagnosed if weight and psychiatric criteria were met as per DSM-IV guidelines.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic Categorizations for Analyses

Variables and Outcomes

Predictor variables for primary analyses were categorical diagnoses of EDNOS, AN, and BN. To examine each separate criterion for AN and BN in the DSM-IV[1], patients with EDNOS were further divided into non-overlapping pAN and pBN categories:

-

1)

Partial BN-Binge/Purge: patients who binge eat and purge (defined by self-induced vomiting only) in the month prior to presentation, but with less frequency than defined in the DSM-IV.

-

2)

Partial BN-Binge only: patients who binge eat with no purging behaviors, similar to binge eating disorder (BED) but with any level of frequency of binge eating.

-

3)

Partial BN-Purge only: patients who purge with no binge eating behaviors.

-

4)

Partial AN-Low Weight/Menstruating: patients who met weight criteria for AN but not menstrual criteria.

-

5)

Partial AN-Low Weight/Not Menstruating: patients meeting menstrual and weight criteria for AN but not openly acknowledging psychiatric criteria, although exhibiting denial of the severity of their underweight along with weight and shape concerns by parental report sufficient to diagnose a clinical eating disorder.

-

6)

Partial AN-Less Than 90%: patients meeting menstrual criteria for AN who weighed more than 85% median body weight but less than 90%.

-

7)

Partial AN-25%: patients not in other categories of pAN or pBN, but who had lost more than 25 percent of pre-morbid weight at presentation. The DSM-III suggested patients with this degree of weight loss be eligible for the diagnosis of AN, even if they were not below 85% MBW,[33] though this convention was dropped for the DSM-IV.

Medical outcome variables were defined in Table 1, based on national guidelines for acute hospitalization in ED adolescents.[2, 32, 34] Primary outcomes were heart rate, blood pressure, temperature and QTc interval. Severe malnutrition was not a primary outcome in this study as pAN and pBN categories were partly defined by weight. Secondary outcome variables included rates of admission within two weeks of presentation, length of disease, complications attributed to the ED occurring prior to presentation, and complications occurring during the first hospital stay, if the hospitalization occurred within 2 weeks of presentation. There were no deaths in this series during the first hospital stay.

Table 1.

Medical Outcome Variables

| Bradycardia* | < 50 beats per minute |

|

| |

| Hypotension* | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg |

|

| |

| Orthostatic by heart rate | > 20 beat rise in heart rate from lying to standing |

|

| |

| Orthostatic by blood pressure | > 10 point drop in systolic blood pressure from lying to standing |

|

| |

| Hypothermia* | Oral temperature < 35.6 degrees Celsius |

|

| |

| QTc prolongation* | QTc interval > 440 ms |

|

| |

| Hypokalemia | Serum potassium < 3.2 |

|

| |

| Hypophosphatemia | Serum phosphorus < 3.0 |

|

| |

| Severe malnutrition | Percentage MBW < 75 |

|

| |

| Serious complications prior to first visit (obtained from the medical record as a report from patient, parent, or outside health care professional) | Arrhythmias |

| Ascites | |

| Edema | |

| Hematemesis | |

| Hypokalemia | |

| Hypophosphatemia | |

| Pancreatitis | |

| Pericardial effusion | |

| Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum | |

| Renal calculi | |

| Seizure | |

| Superior mesenteric artery syndrome | |

| Syncope | |

|

| |

| Serious hospital complications (noted by medical team during hospital stay and recorded in the medical record) | Hematemesis |

| Hypokalemia (potassium<3.0) | |

| Hypophosphatemia (phosphorus < 3.0) | |

| Pancreatitis | |

| Pericardial effusion | |

| QTc prolongation >450ms | |

| Refeeding syndrome | |

| Seizure | |

| Serious arrhythmias | |

| Superior mesenteric artery syndrome | |

| Syncope | |

| Transfer to the intensive care unit | |

| Vasopressor requirement | |

Primary outcomes were continuous: heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, and QTc interval.

Heart rates (measured manually) and blood pressures (using a sphygmomanometer) were taken after lying supine for 5 minutes, and standing heart rate and blood pressure were taken after standing for two minutes. If heart rates or blood pressures were low supine, or if significant dizziness was reported, standing vital signs were not obtained. Temperatures were obtained orally using a digital thermometer. Electrocardiograms were performed by trained staff members using a standard 12-lead method. Weights were recorded in gowns with no clothing, and heights obtained using a stadiometer. As electrocardiograms and labs were performed clinically rather than as part of a research protocol, the majority but not all patients had these tests performed (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Description – Overall Dataset

| N | % | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1310 | 15.4 | 2.0 | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | 1273 | |||

| Caucasian | 959 | 75.3 | ||

| Asian | 105 | 8.2 | ||

| Hispanic | 96 | 7.5 | ||

| African American | 14 | 1.1 | ||

| Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.2 | ||

| Other | 96 | 7.5 | ||

|

| ||||

| Diagnosis | 1310 | |||

| Anorexia Nervosa (AN) | 330 | 25.2 | ||

| Bulimia Nervosa (BN) | 162 | 12.4 | ||

| Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) | 811 | 62.4 | ||

| Partial AN (pAN) | 408 | 31.1 | ||

| pAN-Low Weight/Menstruating | 111 | 8.5 | ||

| pAN-Low Weight/Not Menstruating | 130 | 9.9 | ||

| pAN-Less than 90% MBW | 121 | 9.2 | ||

| pAN-25% | 46 | 3.5 | ||

| Partial BN (pBN) | 223 | 17.0 | ||

| pBN-Binge/Purge | 79 | 6.0 | ||

| pBN-Purge Only | 86 | 6.6 | ||

| pBN-Binge Only | 58 | 4.4 | ||

|

| ||||

| Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR) – Breasts | 1020 | |||

| 1 | 54 | 5.3 | ||

| 2 | 51 | 5.0 | ||

| 3 | 120 | 11.8 | ||

| 4 | 332 | 32.5 | ||

| 5 | 463 | 45.4 | ||

|

| ||||

| Hormonal Contraception | 109 | 8.3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Months of disease | 1300 | 15.3 | 14.4 | |

|

| ||||

| Percentage of MBW | 1310 | 89.7 | 18.0 | |

|

| ||||

| Severe malnutrition | 218 | 16.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| Percentage weight loss | 1239 | 17.9 | 10.7 | |

|

| ||||

| Rate weight loss (%/month) | 1176 | 2.2 | 2.1 | |

|

| ||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 1310 | 61 | 15 | |

|

| ||||

| Bradycardia | 333 | 25.4 | ||

|

| ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 1308 | 106 | 11 | |

|

| ||||

| Hypotension | 81 | 6.2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Temperature (degrees Celsius) | 1298 | 36.7 | 0.5 | |

|

| ||||

| Hypothermia | 46 | 3.5 | ||

|

| ||||

| Change in heart rate | 1104 | 18 | 12 | |

|

| ||||

| Orthostatic by Heart Rate | 415 | 37.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| Change in systolic blood pressure | 1104 | 3 | 9 | |

|

| ||||

| Orthostatic by Blood Pressure | 62 | 5.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| QTc interval (milliseconds) | 1088 | 392 | 28 | |

|

| ||||

| QTc Prolongation | 41 | 3.8 | ||

|

| ||||

| Potassium (mmol/liter) | 1179 | 4.0 | 0.4 | |

|

| ||||

| Hypokalemia | 26 | 2.2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 1074 | 3.9 | 0.6 | |

|

| ||||

| Hypophosphatemia | 54 | 5.0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Met medical admission criteria | ||||

| Any | 848 | 64.7 | ||

| Any except weight | 790 | 60.3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Status at initial evaluation/presentation | ||||

| Outpatient | 685 | 52.3 | ||

| Inpatient | 624 | 47.7 | ||

|

| ||||

| Admitted to hospital or admission recommended within 2 weeks of first presentation | 894 | 68.3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Length of stay (days) if admitted | 890 | 17.3 | 11.7 | |

|

| ||||

| Serious hospital complications if hospitalized within 2 weeks of presentation | 169 | 19.0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Serious complications reported prior to presentation | 266 | 20.2 | ||

Percentage Median Body Weight (MBW)

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the equation: BMI = weight in kilos/(height in meters)2. BW was calculated using gender-specific 2000 CDC BMI-for-age growth charts for children and adolescents aged 2–20 years (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts). The 50th percentile BMI for exact age at presentation on the CDC chart was used to calculate an MBW, together with the height at presentation.

Rate of Weight Loss

Reported maximum weights were extracted from the medical record. Total weight loss prior to presentation was defined as the maximum weight minus the weight at presentation. Total percentage weight loss was defined as the total weight loss divided by the maximum weight, multiplied by 100. The rate of weight loss was defined as total percentage weight loss divided by the months from the date of maximum weight to the date of presentation. If the maximum weight was the weight at presentation, the total weight loss was zero, as was the rate of weight loss.

Statistical Analysis

Data were described with standard mean and frequency statistics, and analyzed using chi-squared testing, Student's t-testing, and ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc comparisons testing on SPSS v17.0 software. In order to guard against Type I error in analysis of the primary aims, a Hochberg modified Bonferroni procedure was employed.[35] To further assess relationships between primary predictor and outcome variables, age and length of disease were added as covariates using ANCOVA.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2. Table 3 outlines medical differences between DSM-IV ED categories at presentation. The medical severity of EDNOS patients fell between that of subjects with AN and BN in most criteria examined. Differences were statistically significant for all primary outcomes. Pediatric patients with EDNOS had similar age, length of disease, and rate of weight loss as those with AN, but otherwise post hoc testing revealed that most differences in secondary outcomes were significant between all three diagnostic categories.

Table 3.

Comparison of EDNOS to AN and BN

| AN | EDNOS | BN | Chi | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.3 | 15.2 | 16.4 | 26.6***,1 | |

|

| |||||

| Months disease | 14.0 | 13.7 | 26.6 | 61.7***,1 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean %MBW | 75.8 | 92.0 | 106.6 | 242.6***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| % Severe malnutrition | 38.2 | 11.2 | 0 | 159.9*** | |

|

| |||||

| Mean % weight loss | 23.0 | 16.6 | 13.2 | 62.2***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean rate loss (%/mo) | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 12.9***,1 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean heart rate | 56 | 63 | 66 | 31.9***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| % Bradycardia | 38.5 | 23.3 | 9.3 | 53.9*** | |

|

| |||||

| Mean systolic blood pressure | 101 | 107 | 111 | 68.7***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| % Hypotension | 16.4 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 79.3*** | |

|

| |||||

| Mean temperature | 36.6 | 36.7 | 36.9 | 21.6***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| % Hypothermia | 5.8 | 3.3 | 0 | 10.8** | |

|

| |||||

| Mean change in heart rate | 18 | 19 | 17 | 1.8 | |

|

| |||||

| % Orthostatic by Heart Rate | 32.8 | 40.1 | 33.3 | 5.5† | |

|

| |||||

| Mean change in blood pressure | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.1 | |

|

| |||||

| % Orthostatic by Blood Pressure | 6.7 | 5.6 | 3.9 | 1.4 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean QTc interval | 388 | 393 | 401 | 10.3***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| % QTc Prolongation | 4.2 | 3.2 | 6.0 | 2.5 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean serum potassium | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 0.3 | |

|

| |||||

| % Hypokalemia | 2.2 | 1.7 | 4.8 | 5.6† | |

|

| |||||

| Mean serum phosphorus | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 14.6***,3 | |

|

| |||||

| % Hypophosphatemia | 8.3 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 9.4** | |

|

| |||||

| % Met admission criteria | |||||

| Any | 81.8 | 61.6 | 45.7 | 71.4*** | |

| Any except weight | 73.0 | 58.1 | 45.7 | 38.5*** | |

|

| |||||

| Mean length of stay in days | 20.3 | 16.3 | 11.5 | 20.0***,2 | |

|

| |||||

| % Serious hospital complications | 23.2 | 16.5 | 20.3 | 5.7† | |

|

| |||||

| % Serious prior complications | 16.4 | 19.7 | 31.5 | 15.9*** | |

p<.05

p<.01

p≤.001

p<.1

Significant differences on post-hoc testing between AN and BN; EDNOS and BN

Significant differences between all three groups on post-hoc testing

Significant differences between AN and BN; AN and EDNOS

Medical outcomes were compared between subjects with pAN and AN, pBN and BN, and pAN with pBN (Table 4). Patients with pAN did not differ from those with AN in sexual maturity rating (SMR), but patients with pBN were slightly less pubertally mature than their BN counterparts (SMR breast 4.5 vs. 4.7, t=2.6, p<.05; pubic hair 4.5 vs. 4.7, t=2.8, p<.01). All differences noted in primary analyses detailed in Tables 3 and 4 retained significance after the Hochberg modified Bonferroni correction was applied, except for those related to temperature differences between pBN and BN patients. Of note, all relationships between primary predictor and outcome variables remained significant after controlling for age and months of disease.

Table 4.

Comparisons of Medical Data Among Diagnostic Subgroups

| pAN | AN | Chi/t | pBN | BN | Chi/t | pAN vs. pBN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.0 | 15.3 | 2.3* | 15.7 | 16.4 | 4.1*** | −4.5*** |

|

| |||||||

| Months disease | 12.0 | 14.0 | 2.2* | 18.1 | 26.6 | 4.9*** | −5.5*** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean %MBW | 82.2 | 75.8 | −10.6*** | 104.7 | 106.6 | 1.1 | −19.5*** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean % weight loss | 20.2 | 23.0 | 3.6*** | 12.8 | 13.2 | 0.3 | 8.3*** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean rate loss (%/mo) | 2.7 | 2.4 | −2.1* | 1.9 | 1.4 | −2.2* | 3.9*** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean heart rate | 61 | 56 | −4.3*** | 66 | 66 | 0.6 | −3.1** |

|

| |||||||

| % Bradycardia | 28.7 | 38.5 | 7.9** | 12.1 | 9.3 | 0.8 | 22.5*** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean systolic blood pressure | 105 | 101 | −5.0*** | 111 | 111 | −0.04 | −8.1*** |

|

| |||||||

| % Hypotension | 5.1 | 16.4 | 25.3*** | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 5.7* |

|

| |||||||

| Mean temperature | 36.7 | 36.6 | −2.4* | 36.8 | 36.9 | 2.1† | −2.9** |

|

| |||||||

| % Hypothermia | 5.2 | 5.8 | .2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 7.4** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean change in heart rate | 19 | 18 | −1.6 | 19 | 17 | −1.1 | 0.4 |

|

| |||||||

| % Orthostatic by Heart Rate | 42.0 | 32.8 | 5.0* | 38.2 | 33.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean change in systolic blood pressure | 3 | 2 | −1.3 | 4 | 3 | −0.5 | −1.0 |

|

| |||||||

| % Orthostatic by Blood Pressure | 6.8 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean QTc interval | 390 | 388 | −0.8 | 399 | 401 | 0.7 | −3.7*** |

|

| |||||||

| % QTc prolongation | 2.5 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean serum potassium | 4.0 | 3.9 | −0.4 | 4.0 | 4.0 | −0.4 | −0.3 |

|

| |||||||

| % Hypokalemia | 1.3 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 0.4 | 2.2 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean serum phosphorus | 3.9 | 3.8 | −3.6*** | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.3 | −0.9 |

|

| |||||||

| % Hypophosphatemia | 5.2 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

|

| |||||||

| % Severe malnutrition | 22.5 | 38.2 | 21.4*** | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| % Met admission criteria | |||||||

| Any | 71.1 | 81.8 | 11.5*** | 47.5 | 45.7 | 0.1 | 34.2*** |

| Any except weight | 64.0 | 73.0 | 6.9** | 47.5 | 45.7 | 0.1 | 16.0*** |

|

| |||||||

| Mean length of stay in days | 17.8 | 20.3 | 2.6* | 13.8 | 11.5 | −1.5 | 3.1** |

|

| |||||||

| % Serious hospital complications | 18.2 | 23.2 | 2.4 | 19.0 | 20.3 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

|

| |||||||

| % Serious prior complications | 18.1 | 16.4 | 0.4 | 25.1 | 31.5 | 1.9 | 4.3* |

p≤.05

p<.01

p≤.001

Did not retain significance when Hochberg modified Bonferroni correction applied

In exploratory analyses, pAN subgroups were compared to AN and pBN subgroups to BN. Partial AN-Low Weight/Menstruating patients were significantly older, while those not meeting psychiatric criteria were the youngest (15.8 years vs. 14.3: pAN-Low Weight/Not Menstruating, 14.8: pAN-Less than 90%, 15.0: pAN-25%, and 15.3: AN, F=9.7, p<.001). Partial AN-Low Weight/Not Menstruating patients had the longest QTc intervals (394 vs 393: pAN-Low weight/Menstruating, 386: pAN-Less than 90%, 378: pAN-25%, F=3.0, p<.05), The pAN-25% group, despite being nearly at their MBW (97.7% MBW vs. 77.7: pAN-Low weight/Menstruating, 75.7: pAN-Low Weight/Not Menstruating, 87.2: pAN-Less than 90%, and 75.8: AN, F=198.8, p<.001), demonstrated the highest percentage of weight lost (34.0 vs. 19.6, 16.6, 19.2, and 23.0, F=32.9, p<.001) at the fastest rate (3.5%/month vs. 2.6, 2.8, 2.4, and 2.4, F=3.9, p≤.005). They also had higher rates of bradycardia (43.5% vs. 22.5, 28.5, 28.9, and 38.5, χ2=14.4, p<.01) and orthostasis by heart rate (57.1% vs., 52.7, 37.0, 32.4, and 32.8, χ2=18.0, p≤.001) than all other pAN subgroups. Patients in the pAN-Less than 90% group were more likely than all except AN to meet any admission criteria, excluding weight (76.1% vs. 66.7, 61.5, 59.5, and 73.0, χ2=11.8, p<.05). Patients with AN were most likely to be hypotensive (16.2% vs. 2.7: pAN-Low weight/Menstruating, 6.9: pAN-Low weight/Not Menstruating, 5.0: pAN-Less than 90%, and 6.5: pAN-25%, χ2=26.6, p<.001), and had the lowest phosphorus levels (3.7 vs. 3.9, 4.0, 3.9, and 3.8, F=3.7, p≤.005). There were no differences noted among pAN subgroups and AN with regards to rates of hypothermia, orthostatic hypotension, hypokalemia, serious hospital complications or in complications prior to presentation.

Most pBN subgroups did not show significant differences from each other in medical hospitalization criteria, although small cell sizes precluded meaningful analyses of some categorical outcomes. Patients with BN were older (16.4 years vs. 15.8: pBN-Binge/Purge, 15.6: pBN-Purge only, and 15.6: pBN-Binge only, F=6.4, p<.001) and had disease longer than all pBN subgroups (26.6 months vs. 19.4, 16.5, and 18.7, F=8.5, p<.001). Partial BN-Purge only patients had lost weight faster than BN patients (2.4 % month vs. 1.5: pBN-Binge/Purge, 1.9: pBN-Binge Only, and 1.4: BN, F=3.0, p<.05). There were no differences between groups in mean percentage weight loss, blood pressure, orthostatic changes, potassium and phosphorus levels, length of stay if hospitalized, and complication rates.

Discussion

These analyses reveal that in this adolescent ED population, 62.4% are properly diagnosed with EDNOS, if strictly applying current DSM-IV standards. However, 61.6% of these EDNOS patients meet recommended criteria for medical hospitalization, and are more compromised than BN patients in most medical outcomes. Despite their younger age, they displayed similar disease duration and rates of weight loss, QTc prolongation, orthostasis, and hypokalemia as their full diagnostic counterparts. This is despite the fact that they weighed significantly more than patients with AN. These results do not support our initial hypothesis that EDNOS would be less medically severe than AN or BN.

We proposed new groupings of pAN and pBN patients within the EDNOS group, with each subgroup directly challenging one DSM-IV criterion for AN or BN. When pAN patients were compared to those with AN, there were few differences. pAN patients as a whole were less likely to have a low heart rate or blood pressure, but did not differ from AN patients on most other medical outcomes. Adolescents with pAN were younger and weighed significantly more, but had lost weight more rapidly than those with AN and had a shorter disease duration.

Of pAN subgroups, those EDNOS patients who had lost over 25% of their pre-morbid body weight (pAN-25) appeared more compromised than other subgroups of pAN, and even more than AN patients in some medical outcomes. This is the case despite being at a significantly higher, near “ideal” body weight, reminding us that malnutrition is a complex disease with manifestations at multiple weights. In addition, another pAN subgroup, those not meeting menstrual criteria (pAN-NM), was older, possibly indicating later recognition of the ED.

Patients with pBN were younger, had a shorter duration of disease, weighed less and had lost weight more rapidly than their BN counterparts. However, pBN patients and subgroups did not differ significantly from BN adolescents on most other medical outcomes examined.

When pAN was compared to pBN, pAN patients were more medically severe, with the exception of duration of illness and the QTc interval, where pBN patients had more months of disease and longer QTc intervals. This mirrors our comparison of BN to AN, where BN patients report nearly twice the duration of disease and longer mean QTc intervals. Patients with pAN and pBN were similar only in rates of hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, and orthostasis. This lends credence to the idea that EDNOS is too heterogeneous a category, as patients diagnosed differ more from each other than they do from AN and BN, respectively. EDNOS patients who narrowly miss criteria for AN and BN are often medically compromised and in need of treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the first published comparison of reported complications among ED adolescents from all DSM-IV diagnostic groups. While AN patients certainly had a high rate of objective medical complications observed during their first hospital stays, the complication profiles of other patients was hardly reassuring. Partial AN and pBN patients also displayed high rates of hospital complications at around 18% and 19% respectively, and BN and pBN patients reported significantly higher numbers of serious complications prior to presentation than their AN and pAN peers. While further prospective study is required to confirm these findings, they imply the need to better delineate predictors of complications and medical protocols in each DSM group separately, rather than measuring each group against an AN standard.

Limitations of this study include that it is a clinical sample from a subspecialty ED program, which limits its generalizability. It is also an exclusively female sample, and while it is critical that we better learn how to manage adolescent males with EDs, this study does not inform that pursuit. Data were collected retrospectively, and thus data may be missing for non-random reasons not yet identified. In addition, clinical decisions had been made which influenced the choice of laboratory tests, which may have introduced bias based on medical severity. In general, most variables were missing fewer than 10% of data, but phosphorus levels, electrocardiograms, and orthostatic testing were missing in 10–20% of subjects, thereby necessitating caution in the interpretation of these variables.

A limitation of any study of current medical hospitalization criteria for ED patients is that they were derived from expert consensus and not from longitudinal study. Bradycardia, hypotension, orthostasis, and hypothermia have clearly been shown in studies to be strong indicators of a malnourished state, and have therefore been adopted as indicators of medical severity in patients with EDs.[31–32] In addition, QTc prolongation has been shown to be a risk factor for sudden cardiac death,[36] which makes it the most concerning complication of the ones examined here. However, we do not have evidence that these findings mandate hospitalization, nor are we certain that hospitalization improves long-term medical outcomes. It is possible that in the future outpatient treatment regimens may prove to be equally effective and safe in treating these cardiac sequelae, and further prospective study is urgently needed to delineate the most appropriate type of interventions, and when they are indicated.

These analyses reveal that there exist adolescent ED patients within a larger EDNOS group who are medically similar to AN and BN patients. They provide a rationale to consider changes to the diagnostic criteria for adolescents with ED, as other authors have recently proposed.[3–4, 6, 9, 15–16, 25–26, 37–46] For example, cut-points of weights, duration of behaviors and endocrine dysfunction are not currently evidence-based and thus may not be truly reflective of medical severity.[47] Our study also suggests that current criteria for medical intervention may be most appropriate for adolescents with AN, but that we may miss critical opportunities for intervention and prevention in other ED groups.

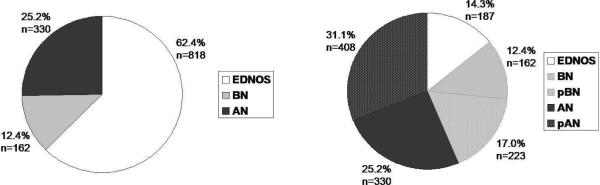

Finally, our data propose another possibility of diagnostic groupings, which are shown in Figure 2, illustrating the original percentage of patients in AN, BN, and EDNOS categories, and comparing that with a new grouping where pAN and pBN are counted as a subgroup of AN and BN, respectively. If patients with pAN and pBN are combined into AN and BN groups, only 14.3% of patients with “true” EDNOS remain, similar to another recent diagnostic reclassification of adult ED patients.[38] If over 60% of patients have EDNOS by DSM-IV criteria, they are effectively forced into diagnostic categories lacking definition, health care coverage, or medical knowledge. In adolescents and children especially, eating disorders are a devastating set of diseases with multiple long-term sequelae. It is clear that a diagnosis of EDNOS does not imply a reassuring medical profile, and these findings underscore the need to intervene early, even when young patients do not meet full diagnostic criteria for AN or BN. Future studies should be directed toward better defining the best clinical criteria by which we can intervene both medically and psychiatrically in these diverse set of illnesses.

Figure 2.

DSM-IV and Proposed Diagnostic Categories

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. Iris Litt for her support and help with editing of this manuscript, and all of the research assistants at the Stanford WEIGHT lab who have assisted with data collection for this study.

Funding disclosure: The project was funded in part by the Stanford Pediatric Research Fund, Jenny Wilson received funding from the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program, and Dr. Lock received funding from NIH K24 MH074467.

Abbreviations

- MBW

Median body weight

- %MBW

Percentage of median body weight

- BMI

Body mass index

- ED

Eating disorder

- EDNOS

Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified

- BN

Bulimia nervosa

- AN

Anorexia nervosa

- pAN

Partial anorexia nervosa

- pBN

Partial bulimia nervosa

- pBN-Binge/Purge

Partial bulimia nervosa, not meeting bingeing and purging frequency criteria

- pBN-Binge Only

Partial bulimia nervosa, bingeing but not purging

- pBN-Purge Only

Partial bulimia nervosa, purging but not bingeing

- pAN-Low Weight/Menstruating

Partial anorexia nervosa, not meeting menstrual criteria

- pAN-Low Weight/Not Menstruating

Partial anorexia nervosa, meeting weight and menstrual criteria

- pAN-Less Than 90%

Partial anorexia nervosa, 85–90% of median body weight

- pAN-25%

Partial anorexia nervosa, lost more than 25% of pre-morbid weight at presentation

- SMR

Sexual maturity rating

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Peebles, Dr. Hardy, Jenny Wilson, and Dr. Lock have no financial or personal relationships that could lead to conflict of interest.

Clinical trial disclosure: This article does not report the results of a clinical trial.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treatment of patients with eating disorders,third edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7 Suppl):4–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bravender T, et al. Classification of child and adolescent eating disturbances. Workgroup for Classification of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents (WCEDCA) Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):S117–22. doi: 10.1002/eat.20458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified“ (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machado PP, et al. The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(3):212–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholls D, Chater R, Lask B. Children into DSM don't go: a comparison of classification systems for eating disorders in childhood and early adolescence. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(3):317–24. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<317::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peebles R, Wilson JL, Lock JD. How do children with eating disorders differ from adolescents with eating disorders at initial evaluation? J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(6):800–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson GT, Shafran R. Eating disorders guidelines from NICE. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):79–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairburn CG, et al. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: implications for DSM-V. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(8):1705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panagiotopoulos C, et al. Electrocardiographic findings in adolescents with eating disorders. Pediatrics. 2000;105(5):1100–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strokosch GR, et al. Effects of an oral contraceptive (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) on bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(6):819–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestergaard P, et al. Fractures in patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other eating disorders--a nationwide register study. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32(3):301–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grilo CM, et al. Natural course of bulimia nervosa and of eating disorder not otherwise specified: 5-year prospective study of remissions, relapses, and the effects of personality disorder psychopathology. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(5):738–46. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Tovim DI, et al. Outcome in patients with eating disorders: a 5-year study. Lancet. 2001;357(9264):1254–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Marchesini G. Is amenorrhea a clinically useful criterion for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa? Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(12):1290–4. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.le Grange D, et al. DSM-IV threshold versus subthreshold bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(6):462–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockert W, Kaplan AS, Olmsted MP. Eating disorder not otherwise specified: the view from a tertiary care treatment center. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):S99–S103. doi: 10.1002/eat.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade TD. A retrospective comparison of purging type disorders: eating disorder not otherwise specified and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry DT, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Comparison of Patients with Bulimia Nervosa, Obese Patients with Binge Eating Disorder, and Nonobese Patients with Binge Eating Disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:589–594. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000087185.95446.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hay P, Fairburn C. The validity of the DSM-IV scheme for classifying bulimic eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(1):7–15. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199801)23:1<7::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizes JS, Sloan Denise M. An Empirical Analysis of Eating Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified: Preliminary Support for a Distinct Subgroup. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23:233–242. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199804)23:3<233::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog DB, Hopkins Julie B., Burns Craig D. A Follow-Up Study of 33 Subdiagnostic Eating Disordered Women. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;14(3):261–267. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199311)14:3<261::aid-eat2260140304>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricca V, et al. Psychopathological and clinical features of outpatients with an eating disorder not otherwise specified. Eat Weight Disord. 2001;6(3):157–65. doi: 10.1007/BF03339765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunnell DW, Shenker I. Ronald, Nussbaum Michael P., Jacobson Marc S., Cooper Peter. Subclinical Versus Formal Eating Disorders: Differentiating Psychological Features. Int J Eat Disord. 1990;9(3):357–362. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh BT, Sysko R. Broad categories for the diagnosis of eating disorders (BCD-ED): An alternative system for classification. Int J Eat Disord. 2009 doi: 10.1002/eat.20722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas JJ, Vartanian LR, Brownell KD. The relationship between eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) and officially recognized eating disorders: meta-analysis and implications for DSM. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(3):407–33. doi: 10.1037/a0015326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keel PK, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2009 doi: 10.1002/eat.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agras WS, et al. A 4-year prospective study of eating disorder NOS compared with full eating disorder syndromes. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(6):565–70. doi: 10.1002/eat.20708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt U, et al. Do adolescents with eating disorder not otherwise specified or full-syndrome bulimia nervosa differ in clinical severity, comorbidity, risk factors, treatment outcome or cost? Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(6):498–504. doi: 10.1002/eat.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eddy KT, et al. Eating disorder not otherwise specified in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(2):156–64. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cd9cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rome ES, Ammerman S. Medical complications of eating disorders: an update. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rome ES, et al. Children and adolescents with eating disorders: the state of the art. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e98–108. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Third Edition. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golden NH, et al. Eating disorders in adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):496–503. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straus SM, et al. Prolonged QTc interval and risk of sudden cardiac death in a population of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(2):362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. An empirical study of the classification of eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):886–95. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S. Eating disorder not otherwise specified in an inpatient unit: the impact of altering the DSM-IV criteria for anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(5):340–9. doi: 10.1002/erv.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keel PK, et al. Application of a latent class analysis to empirically define eating disorder phenotypes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(2):192–200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell JE, et al. Latent profile analysis of a cohort of patients with eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):95–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sloan DM, Mizes JS, Epstein EM. Empirical classification of eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2005;6(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Striegel-Moore RH, et al. An empirical study of the typology of bulimia nervosa and its spectrum variants. Psychol Med. 2005;35(11):1563–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wade TD, Crosby RD, Martin NG. Use of latent profile analysis to identify eating disorder phenotypes in an adult Australian twin cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(12):1377–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson DA, Gleaves DH, Stewart TM. Categorical versus dimensional models of eating disorders: an examination of the evidence. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/eat.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wonderlich SA, et al. Eating disorder diagnoses: empirical approaches to classification. Am Psychol. 2007;62(3):167–80. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thaw JM, Williamson DA, Martin CK. Impact of altering DSM-IV criteria for anorexia and bulimia nervosa on the base rates of eating disorder diagnoses. Eat Weight Disord. 2001;6(3):121–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03339761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson TL A, AE A Critical Examination of the Amenorrhea and Weight Criteria for Diagnosing Anorexia Nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:175–182. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]