Abstract

NFκB is a family of transcription factors involved in immunity and the normal functioning of many tissues. It has been well studied in osteoclasts, and new data indicate an important role for NFκB in the negative regulation of bone formation. In this article, we discuss how NFκB activation affects osteoblast function and bone formation. In particular, we describe how reduced NFκB activity in osteoblasts results in an increase in bone formation via enhanced c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity, which regulates FOSL1 (also known as Fra1) expression. Furthermore, we discuss how estrogen and NFκB crosstalk in osteoblasts acts to oppositely regulate bone formation. Future NFκB-targeting treatments for osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory bone diseases could lead to increased bone formation concurrent with decreased bone resorption.

Introduction

The transcription factor NFκB represents a family of five mammalian proteins (c-Rel, RelA, RelB, NFκB1 and NFκB2) that regulate a wide variety of genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses, among many other functions.1 Some of the genes regulated by NFκB include cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), chemokines, interferons, and antiapoptotic proteins, such as BIRC2 (also known as cIAP1), BIRC3 (also known as cIAP2) and BCL2L1 (also known as Bcl-XL).1 In humans, dysregulation of NFκB activity is associated with, among other diseases, arthritis, autoimmunity, Alzheimer disease, diabetes and osteoporosis.2,3 Thus, components of the signal transduction pathway of NFκB are potential treatment targets in these diseases.

Inactive NFκB dimers reside in the cytoplasm through interaction with one of a family of inhibitory proteins called inhibitors of κB (IκBs). Activation of NFκB occurs through a wide variety of stimuli that lead to the activation of IκB kinase (IKK). IKK is a complex of three subunits: IKKα (also known as IKK1), IKKβ (also known as IKK2), and IKKγ (also known as NEMO). Phosphorylation of IκB by IKK targets the IκB for polyubiquitination and degradation.1 The NFκB homodimers or hetero-dimers can then enter the nucleus and activate transcription.

NFκB in osteoclasts

Osteoclasts are specialized cells of the monocyte–macrophage lineage that are responsible for bone resorption, whereas osteoblasts are responsible for building new bone. During adulthood there is a balance of osteoblasts and osteoclasts that facilitates normal bone remodeling and turnover. An increase in the osteoclast-to-osteoblast ratio has been implicated in osteoporosis, metastatic bone disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

The NFκB pathway in osteoclasts has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.4–6 Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL; also known as TNF ligand superfamily, member 11) is an essential cytokine in osteoclastogenesis, along with macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF).7 RANKL is expressed in osteoblasts, marrow stromal cells and T cells, and binds to the RANK receptor (also known as TNF receptor superfamily, member 11a) on osteoclast progenitor cells.7 Binding of RANKL to the RANK receptor leads to activation of TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6, and subsequent NFκB-mediated upregulation of osteoclast target genes.5

NFκB signaling, activated by RANKL, TNF or IL-1, can lead to the induction of osteoclast differentiation genes, prolonged survival of osteoclasts and increased bone resorption. Two main targets of NFκB in osteoclasts are the transcription factors c-Fos and NFATc1,8 which are transcriptionally upregulated by NFκB in response to RANKL signaling. In parallel, IL-1 activates NFκB to upregulate the expression of osteoclast genes CD40LG (also known as TRAP), CTSK (cathepsin K) and OSCAR (osteoclast associated receptor).9

Treatments targeting the RANKL or NFκB pathway, or both, have the potential to prevent bone degradation. A peptide inhibitor of NFκB activation, which prevents IKKα and IKKβ from binding to IKKγ, has been shown to block osteoclastogenesis and collagen-induced arthritis in mice.10 The RANKL pathway can be inhibited by osteo-protegerin (OPG; also known as TNF receptor superfamily, member 11b), which acts as a decoy receptor for RANKL. Denosumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against RANKL that acts like OPG to neutralize RANKL activity, is currently in late-stage clinical development as a treatment for osteoporosis.3

Genetic models of NFκB in bone

Rela knockout mice are embryonic lethal, preventing study of the effects of RelA on the adult skeleton. Relb knockout mice are viable, with no change in the uninduced osteoclast number and no apparent osteoblast phenotype.11 However, RelB is required for osteoclast differentiation in vitro and for optimal osteoclast induction in response to inflammation in vivo.11

Nfkb1 or Nfkb2 single-knockout mice have no obvious skeletal phenotype or gross skeletal deformities when these genes are targeted for deletion individually. Nfkb1/Nfkb2 double-knockout mice do not form osteoclasts in vivo or in vitro, and have osteopetrosis that can be partially rescued with bone marrow transplantation.12 The incomplete rescue suggests that there are other cell types (possibly osteoblasts or other cells of the microenvironment, such as stromal cells) that contribute to the osteopetrotic phenotype of these mice. However, bone formation in vivo was not evaluated in these mice. Nonetheless, to address the question of the microenvironment, co-cultures of osteoblasts and osteoclasts from wild-type and Nfkb1/Nfkb2 double-knockout mice were established in vitro. Isolated wild-type calvarial osteoblasts are not capable of inducing osteoclastogenesis from splenic precursors derived from Nfkb1/Nfkb2 double-knockout mice, whereas wild-type osteoblasts can induce osteoclast formation from wild-type splenic cells.13 This finding suggests that NFκB1 and NFκB2 are necessary in osteoclasts for osteoclast formation. In addition, osteoblasts from the Nfkb1/Nfkb2 double-knockout mice are also capable of inducing osteoclasts from wild-type splenic cells,13 indicating no role for NFκB1 and NFκB2 in osteoblastic induction of RANKL or in other mechanisms of osteoblastic regulation of osteoclasts. However, a role for NFκB1 and NFκB2 in osteoblast differentiation and mineralization was not examined.

IKKβ, a catalytic subunit of the IKK complex that mediates NFκB activation, has important roles in both osteoblast and osteoclast formation,14 whereas IKKα has no apparent role (or a redundant role). IKKα-deficient mice die shortly after birth and have rudimentary limbs, shorter jaws and absent or truncated tails, among other abnormalities.15 The limb defects are not due to problems in bone or cartilage. Interestingly, replacement of IKKα only in basal epidermal keratinocytes (the transgene is under the transcriptional control of cytokeratin 14 [CK14], creating the CK14–Ikka mouse) can correct the skeletal defects,16 suggesting no role for IKKα in osteoblasts. IkkaAA mice, which are homozygous for a knock-in mutant allele in which the activation loop serines of IKKα—whose phosphorylation is required for its activation—are replaced with ala-nines, are viable with lymphoid defects. Histomorphometric analysis of the bones of IkkaAA mice shows no change in the number of osteoclasts or osteoblasts in comparison to wild-type mice,14 confirming the results observed in CK14–Ikka mice. In comparison, IKKβ knockout mice are embryonic lethal. To study a bone phenotype, conditional IKKβ knockout mice (IkkbΔ) were created using mice with an Mx1 promoter (induced by interferon or polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid) driving Cre-recombinase expression crossed with mice harboring a ‘floxed’ Ikkb allele. In contrast to IkkaAA mice, IkkbΔ knockout mice were osteopetrotic and had decreased numbers of osteoblasts and osteoclasts at 7 months of age compared with wild-type mice.14

To further define how NFκB regulates osteoblast function and bone formation, Chang et al.20 generated transgenic mice in which a dominant negative (DN) IKKγ allele is expressed under the control of the osteoblast-specific bone γ-carboxyglutamate protein 2 (Bglap2; also known as osteo-calcin) promoter. As a result, NFκB activity is inhibited in mature osteoblasts, but not in osteoclasts. The Bglap2-IKK-DN mice have increased bone mineral density (BMD) at the ages of 2 and 4 weeks. The 2-week-old transgenic mice had the same number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts as wild-type mice, but an increased rate of bone formation. Furthermore, inhibition of NFκB in osteoblasts in vitro led to an increase in osteoblast mineralization, demonstrating the cell-autonomous activity of NFκB. Interestingly, there was no change in the number of osteoclasts, suggesting that NFκB in osteoblasts does not control osteoblastic regulation of osteoclastogenesis.1

There is no apparent skeletal phenotype in adult Bglap2-IKK-DN mice: the BMD and bone BV/TV (bone volume/trabecular volume) are increased in the transgenic mice at 2 and 4 weeks of age, but not at 2 or 6 months.20 NFκB activity is high during the development of wild-type bone (J. Chang et al., unpublished data), but not in adult bone, which accounts for the phenotype observed in the young and ovariectomized Bglap2-IKK-DN mice (see below).

While there is no change in the number of osteoblasts in Bglap2-IKK-DN mice, mice with global IKKβ knockout do have decreased osteoblast numbers.14 Osteoclastic IKKβ may have an effect on the number of osteoblasts; however, osteoblast-specific knockout of IKKβ would be needed to verify the differences in the models.

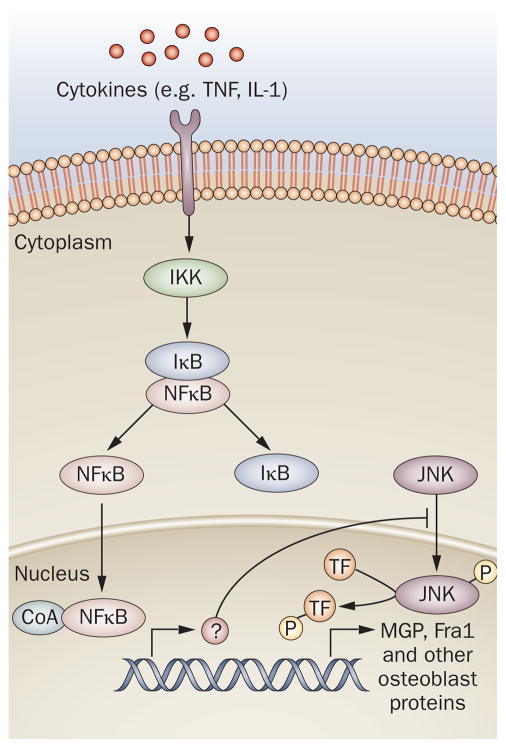

Decreased NFκB activity was found to increase c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity in osteoblasts from Bglap2-IKK-DN mice (Figure 1). NFκB has been shown to upregulate BIRC2 and GADD45B to suppress proapoptotic JNK signaling in fibroblasts17,18 and osteoclasts;19 however, it is not yet known how NFκB regulates JNK in osteoblasts. Is there a direct interaction between NFκB and JNK, or does NFκB increase transcription of a gene that regulates JNK activity as it does in fibroblasts?

Figure 1.

NFκB signaling in osteoblasts. Signaling induced by cytokines, such as TNF, leads to activation of IKK, which releases NFκB from IκB. Activation of NFκB inhibits JNK activity via an unknown mechanism. Inhibition of NFκB leads to enhanced JNK activation and the upregulation of Fra1, which in turn leads to the transcription of MGP and other osteoblast proteins involved in bone formation. Abbreviations: IκB, inhibitor of κB; IKK, IκB kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MGP, matrix Gla protein; TF, transcription factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TRAF, TNF receptor-associated factor.

Activated JNK has been shown to regulate the transcription of activator protein 1 (AP-1) in other tissues. As such, expression levels of several members of the AP-1 family were tested in Bglap2-IKK-DN osteoblasts, and the expression of Fos-related antigen 1 (Fra1; encoded by Fosl1) was shown to be increased (Figure 1).20 The importance of Fra1 in osteoblast function was demonstrated in vitro using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) directed against Fosl1. Knockdown of Fosl1 in osteoblasts resulted in decreased bone matrix mineralization. Knockout of Fosl1 in mice also demonstrates that Fra1 is necessary for bone matrix formation.21

In summary, a reduction in NFκB activity in osteoblasts results in an increase in bone formation via an increase in JNK activity, which regulates Fra1 expression. Julien et al.22 demonstrated that Fra1 directly binds to the promoter of matrix Gla protein (MGP), a key regulator of bone formation. These data suggest that NFκB represses osteoblast mineralization through a series of transcriptional and signaling events in mature osteoblasts.

In addition to a role for NFκB in young, developing mice, studies in ovariecto-mized mice suggest that NFκB is involved in postmenopausal osteoporosis.20 After ovariectomy, Bglap2-IKK-DN mice had less bone loss in the vertebrae and femurs than did wild-type mice owing to a higher bone formation rate, again demonstrating a role for NFκB in the inhibition of osteoblast function and bone formation. Furthermore, Fra1 expression was significantly higher in the osteoblasts of ovariectomized trans-genic mice than in wild-type mice or sham-operated mice.

Inhibition of bone formation

Elevated expression of TNF, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-7 has been detected in a variety of chronic inflammatory bone diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and periodontal diseases. Interestingly, these cytokines are produced by macrophages, lymphocytes, osteoblasts and bone marrow stromal cells23,24 under the regulation of NFκB, and also stimulate NFκB signaling in the target cells. As a result, the number of osteoclasts is increased, leading to bone resorption, and osteoblast activity is repressed, leading to decreased mineralization.

That TNF can inhibit osteoblast differentiation and bone formation is well known. Using two models of osteoblast differentiation—fetal rat calvarial pre-osteoblasts and a murine calvarial clonal osteoblastic cell line (MC3T3-E1)—Gilbert et al.25 found that TNF inhibited cell differentiation by downregulating the transcription of Runx2, which regulates the expression of bone matrix proteins. RUNX2 protein stability has also been shown to be destabilized by TNF.26 Furthermore, TNF also represses the osteoblast transcription factor osterix (OSX).27 As a result of the reduced levels of the key osteoblast transcription factors RUNX2 and OSX, TNF inhibits the expression of the skeletal matrix proteins type I collagen and osteocalcin.28,29

During menopause, as estrogen levels decrease, BMD also decreases. Several papers have suggested different molecular mechanisms to explain this effect of estrogen in bone.30 A decrease in estrogen levels at menopause has been associated with an increase in serum levels of IL-1, IL-6, IL-7 and TNF.23 In addition to repressing cytokine production, estrogen also increases transcription of Fas ligand (also known as CD178) in osteoblasts, which leads to apoptosis of osteoclasts.31

Several hypotheses have been proposed for how 17β-estradiol (E2) can repress proinflammatory cytokines (Figure 2).32 Estrogen receptor α (ER-α) has been shown to associate with NFκB, which prevents NFκB binding to DNA and inhibits transcription of cytokines. A second hypothesis is that ER-α regulates IκB or IKK activity. A third hypothesis is that estrogen-induced ER-α can sequester coactivators (such as TIF2; also known as GRIP1 or NCOA2), p300 or CREBBP (also known as CREB-binding protein [CBP]) away from NFκB. A fourth hypothesis is that ER-α prevents IκB degradation, preventing NFκB activation. However, the studies that gave rise to these hypotheses were not performed in primary osteoblast cells. Whether there is a tissue-specific mechanism of estrogen-mediated repression of NFκB in osteoblasts is unclear.

Figure 2.

Estrogen signaling inhibits NFκB signaling. a | NFκB signaling inhibits osteoblast differentiation and mineralization while increasing transcription of proinflammatory cytokines. b | E2 signaling inhibits NFκB signaling through several possible mechanisms. (1) ER-α might modulate IKK activity. (2) ER-α prevents IκB degradation, preventing NFκB activation. (3) Estrogen-induced ER-α might sequester coactivators (such as TIF2, p300 or CREBBP) away from NFκB. (4) ER-α has been shown to associate with NFκB, preventing NFκB binding to DNA and inhibiting transcription of cytokines. As a result, osteoblast differentiation and mineralization is increased. Abbreviations: CoA, coactivator; ER-α, estrogen receptor α; IκB, inhibitor of κB; IKK, I κB kinase; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

TNF is regulated in opposite directions by E2 and NFκB. Both NFκB and unliganded ER-α are recruited directly to the TNF promoter to activate transcription after treatment with TNF (TNF can upregulate its own transcription in an auto-regulatory loop). Repression of TNF mRNA occurs as early as 30 min after E2 treatment, indicating that TNF is a direct target of E2. E2 leads to recruitment of TIF2, a member of the p160 family of coactivators and corepressors that is a corepressor for TNF,33 and subsequent down-regulation of TNF. E2 did not alter recruitment of NFκB to the TNF promoter.

Mice null for TNF and the TNF type 1 receptor were analyzed for their bone phenotype and showed increased BMD, resulting from elevated bone mineralization. No change in osteoclast number or serum carboxy-terminal collagen crosslinks (CTX, a marker of bone resorption) was observed. Furthermore, blockade of the NFκB pathway using inhibitory peptides enhanced osteoblast differentiation and mineralization.34 In comparison, transgenic mice overexpressing TNF are a well-established model for arthritis and osteoporosis.35 Not only do they have an increased number of osteoclast precursor cells,36 but the osteoblasts from these mice have a diminished capacity for mineralization.26 Together, these mouse models support a role for TNF activation of NFκB in the suppression of osteoblast function.

The post-ovariectomy decrease in BMD observed in mice or rats can be prevented by blocking cytokines that are normally repressed by E2. Independent neutralization of TNF, IL-1, IL-6 or IL-7 has been shown to inhibit bone resorption.37–39 Interestingly, a more favorable outcome is seen when both TNF and IL-1 are blocked compared with blockade of either cytokine alone.40 This was demonstrated in ovariectomized mice treated with either IL-1 receptor antagonist or TNF-binding protein. No effect was seen on bone when TNF and IL-1 were blocked in sham-ovariectomized mice, demonstrating the specificity of this effect to estrogen-regulated pathways.40

To elucidate the pathway downstream of cytokines in osteoblasts, Chang et al.20 used antibodies specific for the active form of the NFκB subunit RelA to show an increase in NFκB activity in osteoblasts after ovariectomy. By contrast, there was little active RelA observed in bones from Bglap2-IKK-DN mice. This is further evidence that estrogen regulates NFκB in osteoblasts in vivo; however, the mechanism of RelA activation remains unknown. More importantly, bone loss was found to be markedly reduced in Bglap2-IKK-DN mice after ovariectomy, suggesting that the activation of NFκB impairs osteoblastic bone formation. Based on our studies described here and other works on osteoclasts, we propose a novel model of osteoporosis: the activation of NFκB due to estrogen deficiency not only promotes osteoclast activation, osteoclast survival and bone resorption, but simultaneously inhibits osteoblast function.

Future research directions

Although better studied in T cells and osteoclasts, it is becoming evident that the NFκB pathway is also important in osteoblasts. Studies have shown a role for RelA in the regulation of the JNK pathway and Fra1. However, RelA is only one piece of the NFκB pathway. What are the receptors and ligands that activate the NFκB pathway in osteoblasts? Cytokines, TNF, bacterial lipo-polysaccharide and viruses are just a few of the agonists that activate NFκB in other tissues.1 Could there be osteoblast-specific agonists or receptors, or both? In osteoclasts, TRAFs 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 regulate NFκB downstream of RANK signaling: which TRAFs, if any, activate IKK in osteoblasts?

In addition to osteoporosis, levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are increased and bone formation is inhibited in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and the gum disease periodontitis. In the future, it will be important to test, by use of IKK-DN mice, whether the activation of NFκB in osteoblasts in these diseases is responsible for the compromised bone formation.

The genes that are directly regulated by NFκB in osteoblasts remain to be identified. While Fra1 is an indirect target of NFκB through the JNK signaling pathway, it is possible that NFκB may induce other genes that directly inhibit osteoblast function. TNF has been found to inhibit the expression of the osteoblast master transcription factors RUNX2 and OSX:25,27 it remains to be determined whether and how NFκB has a role in the inhibition of RUNX2 and OSX via TNF.

Another potential question concerns the function of NFκB at each stage of osteoblast differentiation. The inhibition of NFκB promotes alkaline phosphatase activity, Col1A1 transcription and osteocalcin activity in C2C12 mesenchymal cells. As osteoblasts are derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), it is important to rigidly test whether NFκB has a role in the regulation of osteoblast differentiation from MSCs. MSCs have been proposed for use in tissue regeneration and repair, and if the inhibition of NFκB promotes differentiation, the inhibition of NFκB could help to promote regeneration and to inhibit local inflammation.

Implications for therapy

Currently, many drugs used in the treatment of osteoporosis are bone resorption inhibitors.41 Although these types of drugs inhibit bone resorption, they are unable to increase or restore bone mass in human patients with osteoporosis. As patients with osteoporosis may have lost more than 50% of bone mass at the time of diagnosis, the lack of anabolic activity of antiresorptive agents is a critical shortcoming in this therapeutic approach.42 According to our studies, targeting NFκB might provide a novel and efficacious treatment strategy in patients with osteoporosis or other inflammatory bone diseases. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, which is used to treat multiple myeloma, has been found to promote bone formation by stabilizing RUNX2,43 and it is known that proteasome inhibitors inhibit NFκB by blocking I Ba degradation.1,44 According to our results, bortezomib might also promote bone formation through the inhibition of NFκB. However, it should be pointed out that NFκB has also been found to have a critical role in the inhibition of apoptosis.45,46 As apoptosis of osteoblasts has been suggested to have a role in the development of osteoporosis,47 there could be concerns that the inhibition of NFκB in differentiated osteoblasts might induce massive apoptosis, resulting in more deleterious bone loss. However, we found that the inhibition of NFκB in IKK-DN mice did not increase osteoblast apoptosis in vivo.20 It is well known that various growth factors are highly deposited in the bone marrow and bone matrix. These growth factors may promote cell survival through Akt or ERK signaling pathways and overcome NFκB inhibition. In fact, bone morphogenetic protein signaling has previously been shown to overcome TNF-mediated apoptosis independently of NFκB.48

Conclusions

NFκB has important roles in both osteoblasts and osteoclasts that affect bone regulation. Chang et al.20 have shown that a reduction in NFκB activity in osteoblasts results in an increase in bone formation. Furthermore, we propose that the reduction of NFκB activity mediated by estrogen not only reduces osteoclast activation and bone resorption, but simultaneously increases osteoblast function. Identifying a drug that not only inhibits bone resorption, but also promotes new bone formation, would be a major therapeutic advance. Targeting NFκB could provide a novel and efficacious treatment strategy for osteoporosis and other inflammatory bone diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a K12 BIRCWH grant to S. A. Krum from the NIH/ORWH (HD001400-08) and by DE17684, DE019412, DE016513, DE13848 from National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research and CA100849 from National Cancer Institute to C.-Y. Wang. The authors would like to thank Benny Gee, UCLA Life Sciences, for help with the figures.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

S. A. Krum, J. Chang and C.-Y. Wang researched data for the article. S. Krum, G. Miranda-Carboni and C.-Y. Wang made substantial contributions to the discussion of the article’s content. S. A. Krum, G. Miranda-Carboni and C.-Y. Wang were involved in writing the article. All the authors took part in review/editing of the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109 (Suppl):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granic I, Dolga AM, Nijholt IM, van Dijk G, Eisel UL. Inflammation and NF-κB in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:809–821. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geusens P. Emerging treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis—focus on denosumab. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:241–250. doi: 10.2147/cia.s3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimi E, Ghosh S. Role of nuclear factor-κB in the immune system and bone. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee ZH, Kim HH. Signal transduction by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B in osteoclasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soysa NS, Alles N. NF-κB functions in osteoclasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamashita T, et al. NF-κB p50 and p52 regulate receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and tumor necrosis factor-induced osteoclast precursor differentiation by activating c-Fos and NFATc1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18245–18253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH, et al. The mechanism of osteoclast differentiation induced by IL-1. J Immunol. 2009;183:1862–1870. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimi E, et al. Selective inhibition of NF-κB blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaira S, et al. RelB is the NF-κB subunit downstream of NIK responsible for osteoclast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3897–3902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708576105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iotsova V, et al. Osteopetrosis in mice lacking NF-κB1 and NF-κB2. Nat Med. 1997;3:1285–1289. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franzoso G, et al. Requirement for NF-κB in osteoclast and B-cell development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3482–3496. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruocco MG, et al. IκB kinase (IKK)β, but not IKKα, is a critical mediator of osteoclast survival and is required for inflammation-induced bone loss. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1677–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeda K, et al. Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKα. Science. 1999;284:313–316. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sil AK, Maeda S, Sano Y, Roop DR, Karin M. IκB kinase-α acts in the epidermis to control skeletal and craniofacial morphogenesis. Nature. 2004;428:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature02421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Smaele E, et al. Induction of gadd45β by NF-κB downregulates pro-apoptotic JNK signalling. Nature. 2001;414:308–313. doi: 10.1038/35104560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang G, et al. Inhibition of JNK activation through NF-κB target genes. Nature. 2001;414:313–317. doi: 10.1038/35104568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaira S, et al. RelA/p65 promotes osteoclast differentiation by blocking a RANKL-induced apoptotic JNK pathway in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2088–2097. doi: 10.1172/JCI33392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang J, et al. Inhibition of osteoblastic bone formation by nuclear factor-κB. Nat Med. 2009;15:682–689. doi: 10.1038/nm.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eferl R, et al. The Fos-related antigen Fra-1 is an activator of bone matrix formation. EMBO J. 2004;23:2789–2799. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Julien M, et al. phosphate-dependent regulation of MGP in osteoblasts: role of ERK1/2 and Fra-1. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1856–1868. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeilschifter J, Köditz R, Pfohl M, Schatz H. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:90–119. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R. Estrogen deficiency and bone loss: an inflammatory tale. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1186–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert L, et al. Expression of the osteoblast differentiation factor RUNX2 (Cbfa1/AML3/Pebp2αA) is inhibited by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2695–2701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaneki H, et al. Tumor necrosis factor promotes Runx2 degradation through up-regulation of Smurf1 and Smurf2 in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4326–4333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509430200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu X, Gilbert L, He X, Rubin J, Nanes MS. Transcriptional regulation of the osterix (Osx, Sp7) promoter by tumor necrosis factor identifies disparate effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase and NFκB pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6297–6306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding J, et al. TNF-α and IL-1β inhibit RUNX2 and collagen expression but increase alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization in human mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 2009;84:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert LC, Rubin J, Nanes MS. The p55 TNF receptor mediates TNF inhibition of osteoblast differentiation independently of apoptosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:e1011–e1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00534.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krum SA, Brown M. Unraveling estrogen action in osteoporosis. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1348–1352. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.10.5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krum SA, et al. Estrogen protects bone by inducing Fas ligand in osteoblasts to regulate osteoclast survival. EMBO J. 2008;27:535–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalaitzidis D, Gilmore TD. Transcription factor cross-talk: the estrogen receptor and NF-κB. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cvoro A, et al. Distinct roles of unliganded and liganded estrogen receptors in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell. 2006;21:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, et al. Endogenous TNFα lowers maximum peak bone mass and inhibits osteoblastic Smad activation through NF-κB. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:646–655. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keffer J, et al. Transgenic mice expressing human tumour necrosis factor: a predictive genetic model of arthritis. EMBO J. 1991;10:4025–4031. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, et al. Systemic tumor necrosis factor α mediates an increase in peripheral cD11bhigh osteoclast precursors in tumor necrosis factor α-transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:265–276. doi: 10.1002/art.11419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitazawa R, Kimble RB, Vannice JL, Kung VT, Pacifici R. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor binding protein decrease osteoclast formation and bone resorption in ovariectomized mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2397–2406. doi: 10.1172/JCI117606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jilka RL, et al. Increased osteoclast development after estrogen loss: mediation by interleukin-6. Science. 1992;257:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1621100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weitzmann MN, Roggia C, Toraldo G, Weitzmann L. & Pacifici, R Increased production of IL-7 uncouples bone formation from bone resorption during estrogen deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1643–1650. doi: 10.1172/JCI15687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimble RB, et al. Simultaneous block of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor is required to completely prevent bone loss in the early postovariectomy period. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3054–3061. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.7.7789332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3318–3325. doi: 10.1172/JCI27071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deal C. Future therapeutic targets in osteoporosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:380–385. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832cbc2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukherjee S, et al. Pharmacologic targeting of a stem/progenitor population in vivo is associated with enhanced bone regeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:491–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI33102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-κB pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–765. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-κB. Science. 1996;274:784–787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-κB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kousteni S, et al. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen S, et al. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis by nuclear factor κB-independent bone morphogenetic protein/Smad signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39259–39263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105335200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]