In 1980, Garland and Garland proposed that the lower mortality rates from colorectal cancer in southern regions of the United States might be related to higher sunlight exposure in those areas via a vitamin D-related mechanism (1). Calcium also has modest protective effects against colorectal neoplasia(2). Many epidemiological studies indicate a relationship between intake of calcium and/or vitamin D and colorectal adenoma and cancer incidence(2–4); some clinical trial data support this relationship as well (described in more detail below). Vitamin D and calcium have become agents of great interest and intensive study for the chemoprevention of colorectal cancer, and the report by Fedirko et al. in this issue of the journal (5) addresses several gaps in this area of research. For example, there is a need for more evidence for an effective dose of vitamin D and calcium in human chemoprevention, for increased understanding of how vitamin D and calcium interact to affect colorectal cells, and for further investigations to identify biomarkers of vitamin D/calcium chemopreventive effects and pathways through which vitamin D and calcium exert these effects (6).

Several mechanisms of action for vitamin D and calcium related to chemoprevention have been studied. Vitamin D actions include induction of G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest (7, 8), promotion of cell differentiation, possibly via a pathway involving β-catenin (9, 10), and stimulation of apoptosis (11). Putative biological activities related to the apparently protective effects of calcium in the colon include binding of bile acids (12, 13), decreasing cytotoxicity of fecal water (14), inhibition of cellular proliferation (14, 15) , and induction of apoptosis (16). Although these mechanisms have been well-studied in animal models or in vitro, the paucity of studies of these agents’ potential modes of action within controlled studies of vitamin D and calcium supplementation in humans is an important research gap. This issue was addressed by Fedirko et al. in their translational analysis of apoptosis, an overlapping mechanism of action proposed for both vitamin D and calcium, in clinical-trial specimens.

These investigators conducted a double-blind, 2 ×2 factorial clinical trial in patients randomized to receive calcium carbonate (2.0 g per day) and/or vitamin D (800 IU per day; as cholecalciferol) or placebo. They evaluated the effects of these treatments on two markers of apoptosis, Bax and Bcl-2, in normal colon mucosa. Bax expression increased by a statistically significant 56% along the full length of the colonic crypts among individuals treated with vitamin D (versus placebo); Bax expression increased by a statistically nonsignificant 33% in patients receiving either calcium or calcium plus vitamin D (versus placebo). Therefore, the results of this well-designed study demonstrate that vitamin D supplementation in humans has significant effects on markers of apoptosis, providing support for the biological activity of this treatment regimen. Another research gap addressed by this study is the scant evidence for the minimal doses of calcium and vitamin D required for chemoprevention; this question has yet to be unequivocally clarified despite a substantial body of epidemiological research into the relationship of these agents with cancer risk.

Clinical data addressing the issue of dose come from perhaps the best-known clinical trial of combined calcium and vitamin D, which was conducted within the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) (17). This large trial randomized 18,716 women to receive elemental calcium (1000 mg per day) plus vitamin D (400 IU per day) as cholecalciferol, and 18,106 women to receive matching placebo (17) After a mean follow-up of 7 years, calcium plus vitamin D had no effect on the incidence of colorectal cancer (17). However, a nested case-control study found a statistically significant inverse trend between baseline concentrations of 25(OH)D, the biomarker of vitamin D status, and colorectal cancer incidence among WHI participants overall (p-trend = 0.02)(17). As might be expected, the results of the WHI trial generated several new questions, including the possibilities that the women randomized to the trial already had sufficient vitamin D and calcium intake and thus would not experience increased benefit from the study supplement, or that the WHI dose of vitamin D was too low to provide any protection against developing colorectal cancer (4, 17). Regarding the latter possibility, although WHI women in the calcium plus vitamin D arm had a 28% increase in circulating 25(OH)D concentrations two years post-randomization(17), it has been hypothesized that consumption of the recommended adequate intake (AI) of 400 IU/day of vitamin D would be unlikely to confer marked biological effects among people aged 50–69 years [reviewed by Hollis in ref. (18)]. Consistent with this hypothesis, larger doses of vitamin D than that (400 IU/day) employed in the WHI trial may be necessary for any measurable chemopreventive activity.

This hypothesis gained some support from work by Lappe and colleagues (19), who conducted a clinical trial of supplemental calcium (1400–1500 mg) with or without vitamin D as cholecalciferol (1100 IU) for lowering fracture risk in 1179 women. A statistically significant reduction in all-cancer incidence, a secondary endpoint, occurred in the calcium plus vitamin D arm (odds ratio=0.40; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.20–0.82), with a marginally significant result for calcium treatment alone (odds ratio=0.53; 95% CI=0.27–1.03). Although its number of cancer-endpoint events was relatively small (n=50), this trial highlights the importance of establishing an effective dose of vitamin D and calcium for cancer chemoprevention. The work of Fedirko et al. indicated that a vitamin D dose of 800 IU/day was sufficient to markedly increase Bax expression in adults aged 30–75 years (5). Therefore, although it has been argued that taking greater than 800 IU/day of vitamin D is necessary for optimal health among adults(18), the currently reported work demonstrates that putative chemoprotective effects of 800 IU/day can be detected via biomarker measurements in a human population.

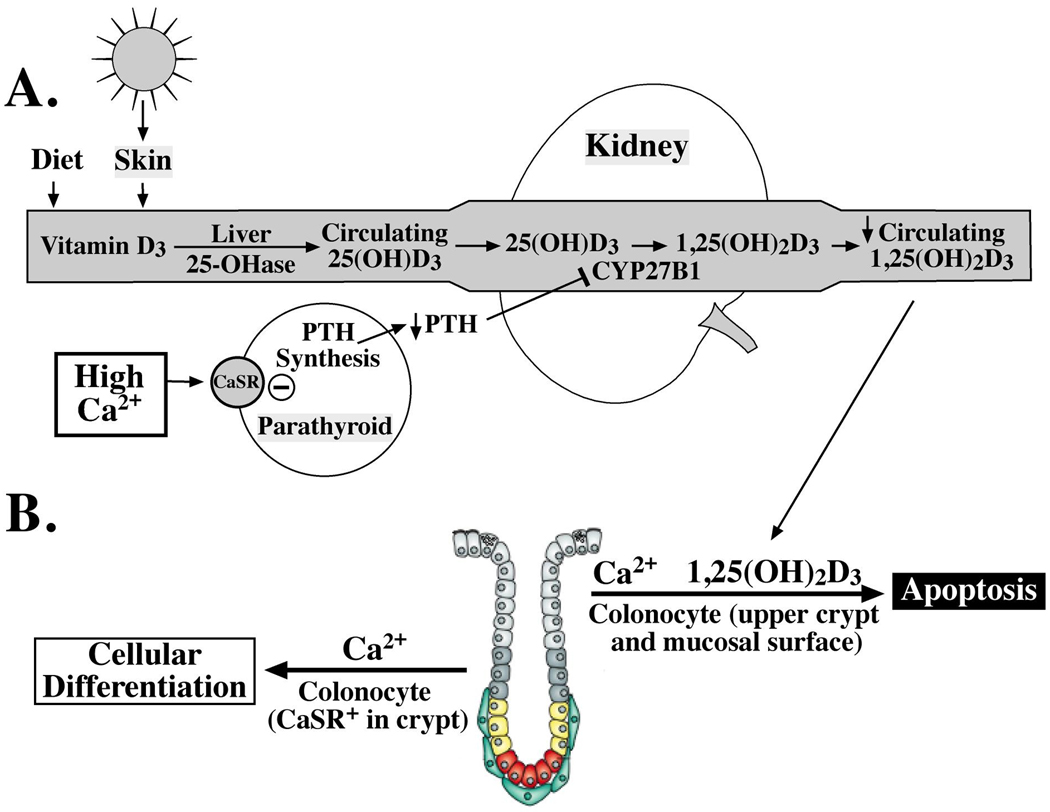

Both the work by Lappe et al. (19) and that of Fedirko et al. highlights the importance of exploring the interaction between calcium and vitamin D, as well as other potentially important contributors to this pathway on cancer endpoints that have been suggested by prior work (20–23). One such factor, estrogen, was examined in the WHI, where some women in the calcium/vitamin D treatment arm were concurrently randomized to either estrogen or placebo (23). The effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on outcome was modified by estrogen treatment (p-interaction = 0.018); women receiving the estrogen placebo plus calcium/vitamin D had a modest reduction in colorectal cancer risk (hazard ratio=0.71; 95% CI=0.46–1.09; versus calcium/vitamin D placebo), and women receiving estrogen plus calcium/vitamin D had a corresponding suggestive increase in this risk [hazard ratio=1.50; 95% CI=0.96–2.33; versus calcium/vitamin D placebo; ref. (23)]. Thus, the biological activity of both agents against carcinogenesis also very likely depends on multiple factors that affect the cellular environment, including hormones and other nutrients. Supporting this concept is the finding of Fedirko et al. that the combination of calcium and vitamin D is not as effective as vitamin D alone on promoting Bax expression. These findings are somewhat contrary to what has been described in some epidemiological and clinical studies (19–21), which suggest that calcium and vitamin D combined may be a more effective regimen than either agent alone against the development of colorectal neoplasia. Puzzling in light of the reported pro-apoptotic effects of both agents, the Fedirko et al. finding suggests that calcium not only did not add to but possibly blunted the apoptotic effects of vitamin D. A potential explanation for this observation comes from Whitfield (24). In normal colon cells, calcium appears to have a role in blocking cellular proliferation and promoting differentiation; however, even at very early stages of carcinogenesis, calcium promotes cellular proliferation and resistance to apoptosis (24). This suggests that calcium may exhibit a functional duality depending on the state of the colonocyte or its location in the crypt; thus, calcium may in some cases have opposing actions to vitamin D-stimulated apoptosis (Figure 1). A further possibility suggested by the Fedirko et al. finding is that the two nutrients may affect apoptosis at different time points. For example, the impact of vitamin D on Bax expression may be more direct and thus earlier (versus that of calcium), and the impact of calcium on this pathway may be more indirect and thus later (versus that of vitamin D) via the release of caspases or by some other regulatory event (16).

Fig. 1.

Interactions between vitamin D and calcium in colorectal carcinogenesis. A, regarding the intricate biological relationship between calcium (Ca2+) and vitamin D homeostasis, higher concentrations of Ca2+ inhibit the secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH); the lack of PTH downregulates CYP27B1 activity, leading ultimately to lower circulating concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3, the hormonal form of vitamin D. In turn, this effect would reduce the 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated apoptosis that is illustrated in panel B [colon crypt modified from Humphries and Wright(27)]. B, calcium has a critical role in regulating cell, or colonocyte, turnover in colon crypts. The presence of calcium may have pro-differentiative and/or pro-apoptotic effects, depending on the state of the cell as well as its location in the crypt. As cells move toward the lumen in normal crypts, the presence of Ca2+ stimulates terminal differentiation via binding to and activation of calcium-sensing receptors (CaSRs). As cells reach the mucosal surface, Ca2+ can induce apoptosis. However, in adenomatous crypts, Ca2+ may actually stimulate proliferation and the production of apoptosis-resistant cells.

Another possibility is related to the intricate biological interactions between calcium and vitamin D, which make it difficult to study the effects of these two nutrients on colorectal neoplasia in isolation(25). The hormonal form of vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D3, has a critical role in calcium homeostasis (26). Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is secreted as calcium concentrations decrease, resulting in increased production of 1,25(OH)2D3. This process in turn increases the absorption of calcium in the gut and stimulates the release of calcium from the bone, which ultimately suppresses PTH secretion (Fig. 1). Because of this tightly regulated feedback loop, the presence of adequate or elevated calcium in the diet may in fact suppress the synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 at the cellular level, or lower the homeostatic set-point for 1,25(OH)2D3 production, which would then attenuate apoptosis stimulated by this active vitamin D metabolite (Fig. 1). Further research should clarify how vitamin D functions in the presence in the presence of other nutrients, particularly calcium.

In summary, epidemiological evidence provides support for calcium and vitamin D as a chemopreventive regimen for colorectal cancer (2–4, 19), and the study by Fedirko et al. (5) is a timely and important contribution of translational science to understanding the underlying biology of vitamin D and/or calcium effects in colorectal carcinogenesis. This study offers additional support for induction of apoptosis as a mechanism of action of vitamin D and provides insight into the minimum dose of vitamin D that may be required to elicit a chemopreventive response in the colon. Nonetheless, further questions remain, particularly about potential interactions between vitamin D and calcium and other factors in the cellular environment.

References

- 1.Garland CF, Garland FC. Do sunlight and vitamin D reduce the likelihood of colon cancer? Int J Epidemiol. 1980;9:227–231. doi: 10.1093/ije/9.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J. Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003548.pub4. (Online) CD003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei MY, Garland CF, Gorham ED, et al. Vitamin D and prevention of colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2958–2969. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt PR. New insights into calcium, dairy and colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4429–4433. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedirko VBR, Flanders WD, et al. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on markers of apoptosis in normal colon mucosa: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cancer Prevention Research. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis CD. Vitamin D and cancer: current dilemmas and future research needs. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2008;88:565S–569S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.565S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang QM, Jones JB, Studzinski GP. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 as a mediator of the G1-S phase block induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in HL60 cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheikh MS, Rochefort H, Garcia M. Overexpression of p21WAF1/CIP1 induces growth arrest, giant cell formation and apoptosis in human breast carcinoma cell lines. Oncogene. 1995;11:1899–1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer HG, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Espada J, et al. Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. The Journal of cell biology. 2001;154:369–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong NA, Pignatelli M. Beta-catenin--a linchpin in colorectal carcinogenesis? Am J Pathol. 2002;160:389–401. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64856-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haussler MR, Haussler CA, Jurutka PW, et al. The vitamin D hormone and its nuclear receptor: molecular actions and disease states. J Endocrinol. 1997;154:S57–S73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newmark HL, Wargovich MJ, Bruce WR. Colon cancer and dietary fat, phosphate, and calcium: a hypothesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;72:1323–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagengast FM, Grubben MJ, van Munster IP. Role of bile acids in colorectal carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipkin M, Newmark H. Effect of added dietary calcium on colonic epithelial-cell proliferation in subjects at high risk for familial colonic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1381–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511283132203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pence BC. Role of calcium in colon cancer prevention: experimental and clinical studies. Mutat Res. 1993;290:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90036-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, et al. Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:6407–6418. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:684–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005;135:317–322. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, et al. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;85:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grau MV, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Vitamin D, calcium supplementation, and colorectal adenomas: results of a randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:1765–1771. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters U, McGlynn KA, Chatterjee N, et al. Vitamin D, calcium, and vitamin D receptor polymorphism in colorectal adenomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1267–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs ET, Martinez ME, Alberts DS. Research and public health implications of the intricate relationship between calcium and vitamin D in the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:1736–1737. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding EL, Mehta S, Fawzi WW, et al. Interaction of estrogen therapy with calcium and vitamin D supplementation on colorectal cancer risk: reanalysis of Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. International journal of cancer. 2008;122:1690–1694. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitfield JF. Calcium, calcium-sensing receptor and colon cancer. Cancer letters. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs ET, Haussler MR, Martinez ME. Vitamin D activity and colorectal neoplasia: a pathway approach to epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2061–2063. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quarles LD. Endocrine functions of bone in mineral metabolism regulation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3820–3828. doi: 10.1172/JCI36479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humphries A, Wright NA. Colonic crypt organization and tumorigenesis. Nature reviews. 2008;8:415–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]