Abstract

In the exploration of sulfur-delivery reagents useful for synthesizing models of the tetracopper-sulfide cluster of nitrous oxide reductase, reactions of Ph3Sb=S with Cu(I) complexes of N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-2R,3R-cyclohexanediamine (TMCHD) and 1,4,7-trialkyltriazacyclononanes (R3tacn; R = Me, Et, iPr) were studied. Treatment of [(R3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6 (R = Me, Et, or iPr) with one equivalent of S=SbPh3 in CH2Cl2 yielded adducts [(R3tacn)Cu(S=SbPh3)]SbF6 (1–3), which were fully characterized, including by X-ray crystallography. The adducts slowly decayed to [(R3tacn)2Cu2(µ-η2: η2-S2)]2+ species (4–6) and SbPh3, or more quickly in the presence of additional [(R3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6 to 4–6 and [(R3tacn)Cu(SbPh3)]SbF6 (7–9). The results of mechanistic studies of the latter process were consistent with rapid intermolecular exchange of S=SbPh3 between 1–3 and added [(R3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6, followed by conversion to product via a dicopper intermediate formed in a rapid pre-equilibrium step. Key evidence supporting this step came from the observation of saturation behavior in a plot of the initial rate of loss of 1 versus the initial concentration of [(Me3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6. Also, treatment of [(TMCHD)Cu(CH3CN)]PF6 with S=SbPh3 led to the known tricopper cluster [(TMCHD)3Cu3(µ3-S)2](PF6)3 in good yield (79%), a synthetic procedure superior to that previously reported (Brown, E. C.; York, J. T.; Antholine, W. E.; Ruiz, E.; Alvarez, S.; Tolman, W. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13752–13753).

Introduction

The environmentally important reduction of N2O to N2 is catalyzed enzymatically by nitrous oxide reductase,1 which has been shown on the basis of X-ray crystallography2 and other spectroscopic techniques3 to contain a unique tetracopper-sulfide cluster supported by multiple histidine residues in its active site. The novel structure of this cluster and hypotheses for the mechanism of N2O coordination and reduction at its copper centers4 has stimulated extensive efforts to create copper-sulfur model complexes supported by N-donor ligands.5,6 These efforts have focused on the use of relatively few types of sulfur-containing reagents (e.g., S8 and Na2S2) in reactions with Cu(I) and Cu(II) species. Studies of the copper-sulfur compounds characterized so far have raised interesting bonding questions,7,8 and, in one instance, have led to the discovery of reactivity with N2O.6 Nonetheless, only a limited array of N-donor ligated copper-sulfur motifs have been characterized and an accurate model of the nitrous oxide active site has yet to be constructed.

In seeking to broaden the scope of available copper-sulfur complexes as a means to address mechanistic and electronic structural issues relevant to the enzyme active site, we are exploring reactions of copper precursors with an expanded array of sulfur-containing reagents. Several studies have shown that triphenyl antimony sulfide (Ph3Sb=S) is useful for sulfur transfer reactions,9 including for the preparation of transition metal sulfide complexes.10,11 The utility of Ph3SbS likely stems from the thermodynamic instability of the Sb-S bond, which is weaker than the related bonds in R3E=S (E = P or As) congeners.12 Herein, we report the results of an investigation of the reactivity of Ph3Sb=S with selected Cu(I) complexes of N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-2R,3R-cyclohexanediamine (TMCHD) and 1,4,7-trialkyltriazacyclononanes (R3tacn; R = Me, Et, iPr). Key findings include the isolation and structural characterization of novel LCu(I)-S=SbPh3 (L = R3tacn; R = Me, Et, iPr) adducts, which are the first examples of transition metal complexes bound to Ph3Sb=S to be structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography.13 These complexes subsequently decay cleanly to [Cu2(µ-η2:η2-S2)]2+ species, particularly when treated with additional [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6, and mechanistic insights for this process were obtained through kinetics studies. In addition, by using, Ph3Sb=S an improved synthetic route to the [Cu3S2]3+ core8 was discovered.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

All solvents and reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used as received unless otherwise noted. The solvents CH2Cl2, pentane, and Et2O were dried over CaH2 and distilled under vacuum or passed through solvent purification columns (Glass Contour, Laguna, CA). The complexes [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 (R = Me,14 Et,15 iPr116), [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]BPh4 (R = Et15 or iPr17), [(Me3tacn)2Cu2(S2)](SbF6)2,14 and [(TMCHD)Cu(CH3CN)]PF6 18 were prepared according to published procedures. All metal complexes were prepared and stored in a glovebox under a dry N2 atmosphere. Triphenylantimony sulfide (Ph3Sb=S) and 2,3-dimethylbutadiene were purchased from Strem and Aldrich, respectively, and were used without purification. NMR spectra were recorded on either Varian VI-300 or VXR-300 spectrometers at ~20 °C. Chemical shifts (δ) were referenced to residual solvent signal and integrated intensities compared to 1,3,5-trimethyloxybenzene added as an internal standard. UV-vis spectra were recorded on an HP8453 (190–1100 nm) diode-array spectrophotometer. Elemental analyses were performed by Robertson Microlit Laboratory (Ledgewood, NJ). Electrospray ionization mass spectra (ESI-MS) were recorded on a Bruker BioTOF II instrument. IR spectra were obtained using a ThermoNicolet Avatar 370 FT-IR.

[(R3tacn)Cu(S=SbPh3)]SbF6 (R = Me (1), Et (2), or iPr (3))

All three complexes were prepared according to this illustrative procedure: In an inert atmosphere, to a solution of the S=SbPh3 (32 mg, 0.083 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added [(Me3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6 (43 mg, 0.083 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). After stirring for 1 h, the mixture was filtered and the volume of the filtrate was reduced to ~1 mL, and Et2O (15 mL) was added, resulting in formation of a yellow precipitate. The supernatant was decanted and the yellow powder was washed with Et2O (3 × 6 mL). The product was isolated in crystalline form by layering Et2O into a concentrated THF solution at −20 °C (65 mg, 92%). Analogous procedures were used to isolate 2 and 3 as yellow crystals in 41% and 32% yields, respectively. 1: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.77-7.61 (m, 15H), 2.59-2.53 Hz (m, 12H), 2.38 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR: (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 134.37, 133.44, 130.97, 55.03, 49.02 ppm. UV-vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH2Cl2]: 356 (2100). Anal. Calcd for C27H36CuF6N3SSb2: C, 37.90; H, 4.24; N, 4.91. Found: C, 37.77; H, 4.24; N, 4.99. ESI-MS: [Cu(Me3tacn)(S=SbPh3)]+ calc. m/z 620.0, found 620.3. FT-IR: 2859.2, 1480.5, 1460.1, 1437.5, 1363.4, 1300.0, 1152.8, 1130.2, 1089.4, 1065.5, 1017.0, 966.3, 984.1, 889.5, 773.5, 751.3, 735.4, 692.4, 656.4 cm−1. 2: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.74-7.60 (m, 15H), 2.60-2.53 Hz (m, 18H), 1.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 9H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 134.6, 133.4, 130.9, 55.3, 53.3, 13.0 ppm. UV-vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH2Cl2]: 356 (2300). Anal. Calcd for C30H42CuF6N3SSb2: C, 40.13; H, 4.72; N, 4.68. Found: C, 39.76; H, 4.70; N, 4.65. ESI-MS: [Cu(Et3tacn)(S=SbPh3)]+ calc. m/z 662.0, found 662.2. FT-IR: 2972.4, 1479.3, 1437.6, 1378.9, 1347.9, 1315.0, 1136.6, 1124.9, 1067.4, 1041.1, 1031.4, 995.7, 928.8, 897.9, 876.2, 860.3, 851.7, 827.1, 812.7, 796.8, 751.0, 739.1 cm−1. 3: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.73-7.59 (m, 15H), 2.66-2.61 Hz (m, 9H), 2.47-2.44 Hz (m, 6H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 18H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 138.75, 134.69, 133.38, 130.91, 58.29, 50.83, 19.70 ppm. UV-vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH2Cl2]: 356 (2300). Anal. Calcd for C33H48CuF6N3SSb2: C, 42.17; H, 5.15; N, 4.47. Found: C, 42.11; H, 5.23; N, 4.46. ESI-MS: [Cu(iPr3tacn)(S=SbPh3)]+ calc. m/z 704.1, found 704.3. FT-IR: 2965.7, 1491.5, 1478.4, 1437.0, 1386.8, 1368.5, 1351.5, 1299.1, 1265.1, 1167.0, 1129.4, 1067.2, 1020.3, 995.7, 968.1, 856.7, 841.0, 750.3, 737.9, 721.3, 692.6, 656.5 cm−1.

[(Et3tacn)2Cu2(µ-S2)](BPh4)2 (5)

Elemental sulfur (1.8 mg, 0.007 mmol) was added to a solution of [(Et3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]BPh4 (36 mg, 0.056 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL). After stirring for 2 h, solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield a brown solid. The brown solid was washed with Et2O (2 × 6 mL), extracted with DMF (2 mL), and then filtered. Slow diffusion of Et2O into the dark brown filtrate at room temperature afforded the product as deep green crystals (16 mg, 46%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, d7-DMF): δ = 7.32 (s, 16H), 6.96 (t, 16H), 6.81 (t, 8H), 3.16-3.09 Hz (m, 36H), 1.36 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 18H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, d7-DMF): δ = 137.11, 135.71, 126.33, 122.62, 93.84, 56.04, 54.64 and 12.39 ppm. UV-vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in DMF]: 410 (7400), 378 (7600). Anal. Calcd for C72H94B2Cu2N6S2: C, 68.83; H, 7.54; N, 6.69. Found: C, 68.45; H, 7.42; N, 6.70. FT-IR: 3052.7, 2978.9, 1579.6, 1478.5, 1465.9, 1386.9, 1270.4, 1258.5, 1144.8, 1122.9, 1069.9, 1033.3, 1018.3, 999.5, 921.0, 862.4, 842.3, 821.8, 792.9, 771.5, 742.3, 732.0, 710.1, 700.6, 668.2 cm−1.

[(iPr3tacn)2Cu2(µ-S2)](BPh4)2 (6)

A similar procedure to that used for the preparation of 5 was followed, except THF was used as the reaction solvent and the product was isolated as dark red crystals from CH2Cl2 at −20 °C (37% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.33 (s, 15H), 7.04 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 14H), 6.89 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 11H), 3.15-3.06 Hz (m, 5H), 2.95-2.74 (m, 4H), 2.65-2.46 (m, 11H), 2.33-2.20 (m, 10H), 1.26-1.08 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 36H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 136.44, 126.22, 122.42, 60.47, 51.75, 45.10, 19.79 and 18.46 ppm. UV-vis [λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1) in CH2Cl2]: 476 (7200), 380 (11000). Anal. Calcd for C78H106B2Cu2N6S2: C, 69.88; H, 7.97; N, 6.27. Found: C, 69.91; H, 7.78; N, 6.24. FT-IR: 3053.5, 2978.0, 1579.8, 1480.7, 1467.0, 1451.0, 1426.7, 1390.1, 1369.2, 1347.1, 1291.9, 1268.7, 1166.3, 1141.9, 1129.4, 1067.3, 1046.6, 1033.5, 962.4, 943.1, 841.7, 761.0, 749.3, 734.1, 705.6, 680.6, 668.1 cm−1.

[(R3tacn)Cu(SbPh3)]SbF6 (7, R = Me; 8, R = Et; 9, R = iPr)

These complexes were prepared similarly, according to the following representative procedure for 7. In an inert atmosphere, to a solution of SbPh3 (40.0 mg, 0.113 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added [(Me3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6 (58.0 mg, 0.113 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). The mixture was stirred 3 h, filtered, and the volume of the filtrate was reduced to ~1 mL under reduced pressure. A portion of Et2O (15 mL) was added to yield a white precipitate. The supernatant solution was decanted and the white powder was washed three times with Et2O (3 × mL). The white product was recrystallized by diffusion of Et2O into a concentrated CH2Cl2 solution at room temperature to generate the product as colorless crystals (71 mg, 76 %). 7: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.48-7.43 (m, 15H), 2.90 Hz (s, 12H), 2.73 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 135.87, 130.89, 130.27, 55.98, 50.69 ppm. Anal. Calcd for C27H36CuF6N3Sb2: C, 39.37; H, 4.41; N, 5.10. Found: C, 38.87; H, 4.61; N, 4.86. ESI-MS: [Cu(Me3tacn)(SbPh3)]+ calc. m/z 588.0, found 588.1. FT-IR: 1463.1, 1434.1, 1363.8, 1299.2, 1153.8, 1127.8, 1085.8, 1069.8, 1057.1, 1015.0, 1000.3, 985.9, 768.3, 737.6, 697.7 cm−1. 8 (68% yield): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.48-7.41 (m, 15H), 2.90-2.85 Hz (m, 18H), 1.15 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 9H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 135.85, 130.88, 130.26, 56.87, 54.68, 14.46 ppm. Anal. Calcd for C30H42CuF6N3Sb2: C, 41.62; H, 4.89; N, 4.85. Found: C, 41.50; H, 5.20; N, 4.92. ESI-MS: [Cu(Et3tacn)(S=SbPh3)]+ calc. m/z 662.0, found 662.2. FT-IR: 1434.2, 1375.8, 1338.5, 1121.2, 1067.2, 1037.6, 999.7, 931.38, 768.2, 737.3, 699.67 cm−1. 9 (70 % yield): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.49-7.41 (m, 15H), 3.15-3.11 (m, 3H), 2.93-2.89 Hz (m, 6H), 2.80-2.75 Hz (m, 6H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 18H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 135.9, 130.85, 130.25, 59.69, 51.77, 20.13 ppm. Anal. Calcd for C33H48CuF6N3Sb2: C, 43.66; H, 5.33; N, 4.63. Found: C, 43.30; H, 5.72; N, 4.62. ESI-MS: [Cu(iPr3tacn)(SbPh3)]+ calc. m/z 672.1, found 672.2. FT-IR: 1434.4, 1389.4, 1367.0, 1347.1, 1161.7, 1123.2, 1066.5, 997.3, 964.31, 756.2, 739.2, 720.6, 699.6 cm−1.

[(TMCHD)3Cu3(S)2](PF6)3 (12)

In an inert atmosphere, to a solution of the [(TMCHD)Cu(NCCH3)]PF6 (31 mg, 0.073 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added S=SbPh3 (29 mg, 0.049 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). After the mixture was stirred for 2 h, it was filtered and the solvent was removed from the filtrate under vacuum to yield a deep green solid, which was washed with Et2O (3 × 6 mL). The deep green powder obtained was crystallized from CH2Cl2 at −20 °C to form dark amber crystals of the product (28 mg, 79%). The product was identified by its X-ray crystal structure and the similarity of its UV-vis spectrum to previously reported data.8a

General Procedures for NMR Kinetics

In a glovebox, appropriate volumes of starting materials in CD2Cl2 were mixed in a vial and the volumes were quickly adjusted to 1 mL so that the concentrations of adducts 1–3 and [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 were 4.7 mM and 47 mM, respectively. The solution was then quickly transferred to a J. Young NMR tube that was removed from glovebox and placed in the spectrometer probe. The progress of the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy at room temperature with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. The initial rates were determined in experiments in which the first 5–10% of the reaction was followed; the rate constants were obtained by linear fitting of the initial rate change. In the experiments with 2,3-dimethylbutadiene, identical procedures were used except 20 equivalents of 2,3-dimethylbutadiene was added to the mixture. Data analysis and graphical representations were performed using the program Kaleidagraph.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of LCu(I)-S=SbPh3 Adducts and [L2Cu2(S2)]2+ Decay Products

Reaction of [(R3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6 (R = Me, Et, or iPr) with one equivalent of S=SbPh3 in CH2Cl2 yielded adducts 1–3, respectively, as yellow crystalline solids (Scheme 1). The complexes are stable in the solid state when stored under nitrogen, but in solution they decompose slowly (see below). The formulations of 1–3 are based on NMR, UV-vis, and FT-IR spectroscopy, CHN analysis, ESI-MS, and X-ray crystallography. Notable identifying features include (a) 1H NMR spectra with sharp peaks in the diamagnetic region and multiplets for the Ph3Sb=S hydrogen atoms shifted ~0.2–0.3 ppm downfield from uncomplexed Ph3Sb=S (Figure S1), (b) a shoulder in UV-vis spectra with λmax at ~350 nm (ε = ~2100–2300 M−1cm−1), and (c) parent ions [(R3tacn)Cu(SSbPh3)]+ with appropriate isotope patterns in ESI mass spectra (Figure S2).

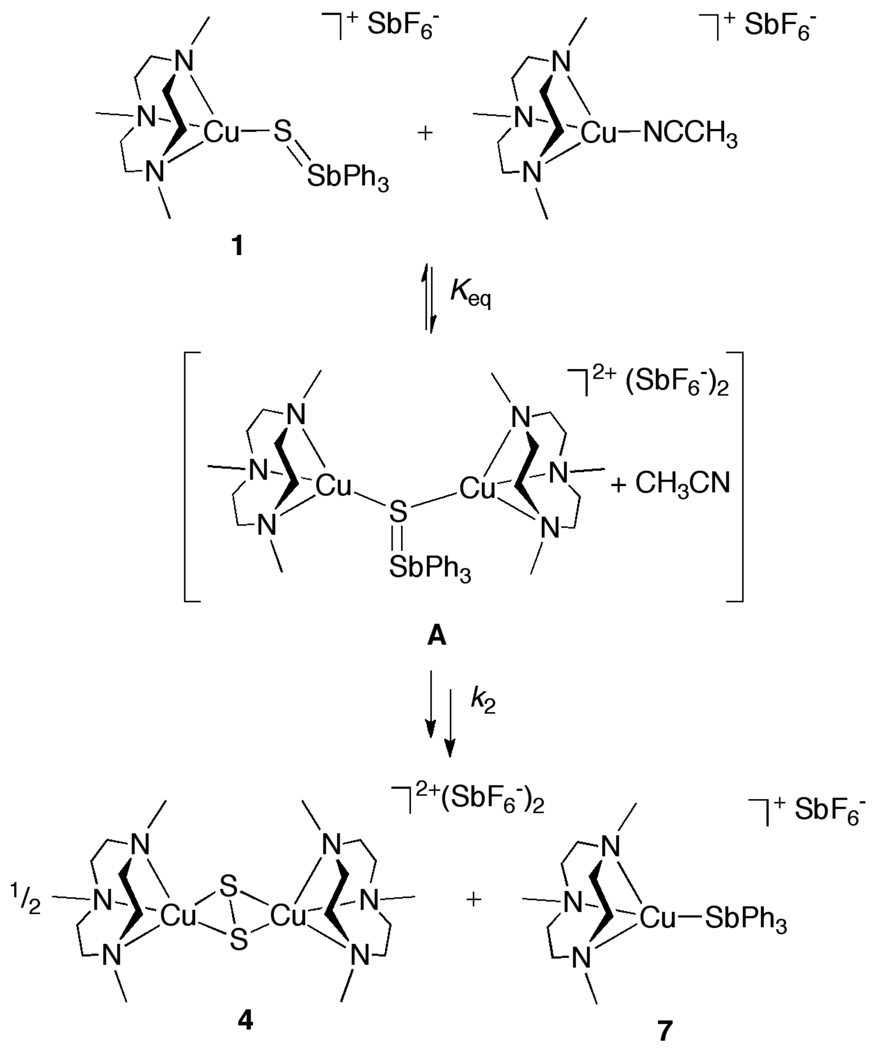

Scheme 1.

Reactions of Cu(I)-S=SbPh3 adducts.

The X-ray crystal structures of complexes 1–3 are shown in Figures 1 (1) and S3 (2 and 3), with selected bond distances and angles listed in Table 1. To our knowledge, they represent the first such structures with Ph3Sb=S coordinated to a metal center.19 They contain similar four-coordinate Cu(I) centers with highly distorted tetrahedral geometries characterized by τ4 values: 0.640 (1), 0.657 (2), and 0.634 (3).20 Essentially, the distortion involves perturbation of the Cu-S bonds from the idealized trigonal axis towards coplanarity with two of the N-donor atoms on the supporting ligand (N2 and N3 for 1, Figure 1), presumably as a result of steric interactions between the N-donor ligand substituents and the phenyl rings of the coordinated Ph3Sb=S moiety. These steric effects also appear to influence the Cu⋯Sb distance, which increases as the size of the R group of the ligand increases from 3.411 Å (1), 3.490 Å (2), to 3.547 Å (3). The Cu–S–Sb moiety adopts a ‘bent’ conformation with Cu–S–Sb bond angles between 100.1–104.6°. The average Cu–N bond lengths range between 2.06–2.17 Å, comparable to those in other copper(I) complexes of R3tacn ligands.17,21 The Cu–S distances of complexes 1–3 (2.167–2.203 Å) are shorter than typical copper(I)-thioether sulfur interactions (~ 2.30 Å), 22 and longer than copper(I)-thiolate interactions (2.13 ~ 2.18 Å),23 but comparable to known Cu(I)–S=PPh3 complexes (2.21 ~ 2.27 Å).24 Complexation of Ph3Sb=S to the copper center induces little if any change in the S–Sb bonding, as the S–Sb distances in 1–3 (2.281–2.283 Å) are only slightly longer than that in free S=SbPh3 (2.244(1) Å).25

Figure 1.

Representation of the X-ray crystal structure of 1, showing the cationic portion with all non-hydrogen atoms as 50% thermal ellipsoids (H atoms omitted for clarity, only heteroatoms labeled).

Table 1.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) for the X-ray structures of 1–3.a

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu1-N1 | 2.160(2) | 2.006(6) | 2.178(2) |

| Cu1-N2 | 2.107(2) | 2.030(8) | 2.161(2) |

| Cu1-N3 | 2.199(2) | 2.157(4) | 2.166(2) |

| Cu1-S1 | 2.1671(8) | 2.1813(10) | 2.2027(7) |

| S1-Sb1 | 2.2832(7) | 2.2735(9) | 2.2812(7) |

| Cu1⋯Sb1 | 3.411 | 3.490 | 3.547 |

| N1-Cu1-N2 | 84.96(9) | 91.3(3) | 84.52(8) |

| N1-Cu1-N3 | 83.41(8) | 71.1(2) | 84.08(8) |

| N2-Cu1-N3 | 83.96(9) | 82.2(3) | 84.39(8) |

| N1-Cu1-S1 | 114.17(6) | 115.8(2) | 127.05(6) |

| N2-Cu1-S1 | 148.91(7) | 150.2(2) | 143.48(6) |

| N3-Cu1-S1 | 120.92(6) | 117.09(10) | 113.59(6) |

| Cu1-S1-Sb1 | 100.06(3) | 103.14(4) | 104.55(3) |

Estimated standard deviations indicated in parentheses.

By monitoring solutions of 1 in CD2Cl2 by 1H NMR spectroscopy with an internal standard (Figure S4) at 20 °C the slow decay (t1/2 ~12h) of 1 to SbPh3 and the disulfido-dicopper( II) species [(Me3tacn)2Cu2(µ-η2:η2-S2)](SbF6)2 (4) was observed in accordance with the stoichiometry shown in Scheme 1. A similar decay reaction of 2 occurred to yield the respective disulfido-dicopper(II) complex (5, with SbF6− counterion), but at a significantly slower rate (t1/2 ~2d). Complex 3 decayed at a similar rate as 2, but the nature of the product(s) in this case was not clear. The disulfido-dicopper(II) complexes 4–6 formed much more rapidly and with higher yields/conversions upon addition of [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 to solutions of 1–3, but in these reactions the adducts [(R3tacn)Cu(SbPh3)]SbF6 (7, R = Me; 8, R = Et; 9, R = iPr) formed instead of free SbPh3 (Scheme 1).

The disulfido-dicopper(II) complexes 4–6 were identified by comparison of 1H NMR spectra with data reported previously (4)14 or obtained from independently prepared samples of the variants 5 and 6. These latter complexes were isolated as BPh4− salts by treating [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]BPh4 with S8 and were fully characterized by CHN analysis and NMR, FTIR, and UV-vis spectroscopy. Complexes 4–6 share similarly sharp 1H NMR features in the diamagnetic region, consistent with singlet ground states arising from disulfide-mediated antiferromagnetic coupling between the Cu(II) ions. They also share diagnostic S22− → Cu(II) LMCT transitions in UV-vis spectra at λmax 380–400 nm (ε ~8000–14,000). 26,7b In addition, the X-ray structure of 5 was solved (Figure 2). The X-ray structures of 5 is similar to that previously reported for 4,14 as illustrated by analogous S-S (4: 2.165(4) Å; 5: 2.150(1) Å) and Cu-Cu (4: 3.84 Å; 5: 3.88 Å) distances and square pyramidal coordination geometries (τ5 = 0.03 for 4 and 0.01 for 5).28

Figure 2.

Representation of the X-ray structure of 5 (BPh4− salt), showing the dicationic portion with all non-hydrogen atoms as 50% thermal ellipsoids (H atoms omitted for clarity, only heteroatoms labeled). Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg) are as follows: Cu1-N1, 2.202(3); Cu1-N2, 2.017(2); Cu1-N3, 2.003(2); Cu1-S1, 2.2152(8); S1-S1´, 2.1501(14); Cu1⋯Cu1´, 3.876; N1-Cu1-N2, 86.17(10); N1-Cu1-N3, 86.13(10); N2-Cu1-N3, 88.50(10); N1-Cu1-S1, 108.49(7); N2-Cu1-S1, 160.58(7); N3-Cu1-S1, 104.76(8); S1-Cu1-S1´, 58.03(3).

The adducts [(R3tacn)Cu(SbPh3)]SbF6 (7, R = Me; 8, R = Et; 9, R = iPr) formed in the reactions of 1–3 with [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 also were identified by comparison of 1H NMR spectra with data obtained from independently prepared samples. These samples were synthesized in good yield (~70%) from the reaction of SbPh3 with [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6. They were isolated as colorless crystalline solids and were fully characterized by CHN analysis, NMR and FTIR spectroscopy, and ESI-MS. Notably, the mass spectrum for each complex exhibits a parent ion with the appropriate isotope pattern for [(R3tacn)Cu(SbPh3)]+ (illustrated for R = Me in Figure S5).

Mechanistic Studies

A series of experiments were performed in order to gain insight into the reactions of the adducts 1–3 with [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 to yield the disulfido-dicopper( II) complexes 4–6 and the SbPh3 adducts 7–9 (Figure S6). First, the reactions of the complexes with identical supporting ligands under pseudo-first-order conditions (i.e., 1 + 10 equiv. [(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6, 2 + 10 equiv. [(Et3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6, and 3 + 10 equiv. [(iPr3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6) in CD2Cl2 were monitored as a function of time by 1H NMR spectroscopy. At initial concentrations [1–3]0 = 4.7 mM at 20 °C, the consumption of 1–3 followed first-order kinetics (Figures S6 and S7). The rates measured for the reactions of 2 and 3 are similar, with both being >~10 times slower than that of 1, as reflected by the measured kobs values (averages from 3 replicate runs) of 6.6(5) × 10−4 s−1 (1), 8.4(1) × 10−5 s−1 (2), and 6.0(4) × 10−5 s−1 (3). The results are roughly consistent with the relative steric profiles of the reactant pairs (1 < 2 ~ < 3) and support a mechanism wherein steric interactions among the reactant pairs influence the rate (e.g., involving interaction of the Cu(I)-S=SbPh3 adduct with the added Cu(I) reactant).

To further test this hypothesis, reactions of [(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 with 1 were examined by measuring initial reaction rates of disappearance of 1 as a function of [[(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6]0 (Figure 3). The initial rate saturates as the initial concentration of the added Cu(I) reagent increases. This finding is consistent with a mechanism (Scheme 2) involving an initial rapid pre-equilibrium (Keq) involving formation of a dicopper intermediate (A) followed by a rate-determining product formation step (k2). The fit of the data to the corresponding eq. 1 is shown in Figure 3 (solid line), yielding Keq = 200 M−1 and k2 = 1.2 × 10−4 s−1. The proposed structure for A is speculative, as it was not observed directly. While the product formation process from A (k2) must involve multiple steps, including a step in which a second sulfur atom is added, the decay of 1 is first order in [1] (see above) which implies that a unimolecular reaction of A is rate-controlling (e.g., cleavage of the S-Sb bond).

| eq. (1) |

Figure 3.

Plot of the initial rate of decay (1H NMR) of 1 vs. [[(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6]0 for the reaction of 1 with [(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 to yield 4 and 7 in CD2Cl2 at 20 °C. Each data point is an average of data for 3 replicate runs. Error bars span the range of values for the replicate runs. The line is a fit of the data to eq. 1 (R = 0.95).

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of 4 from the reaction of 1 with [(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6.

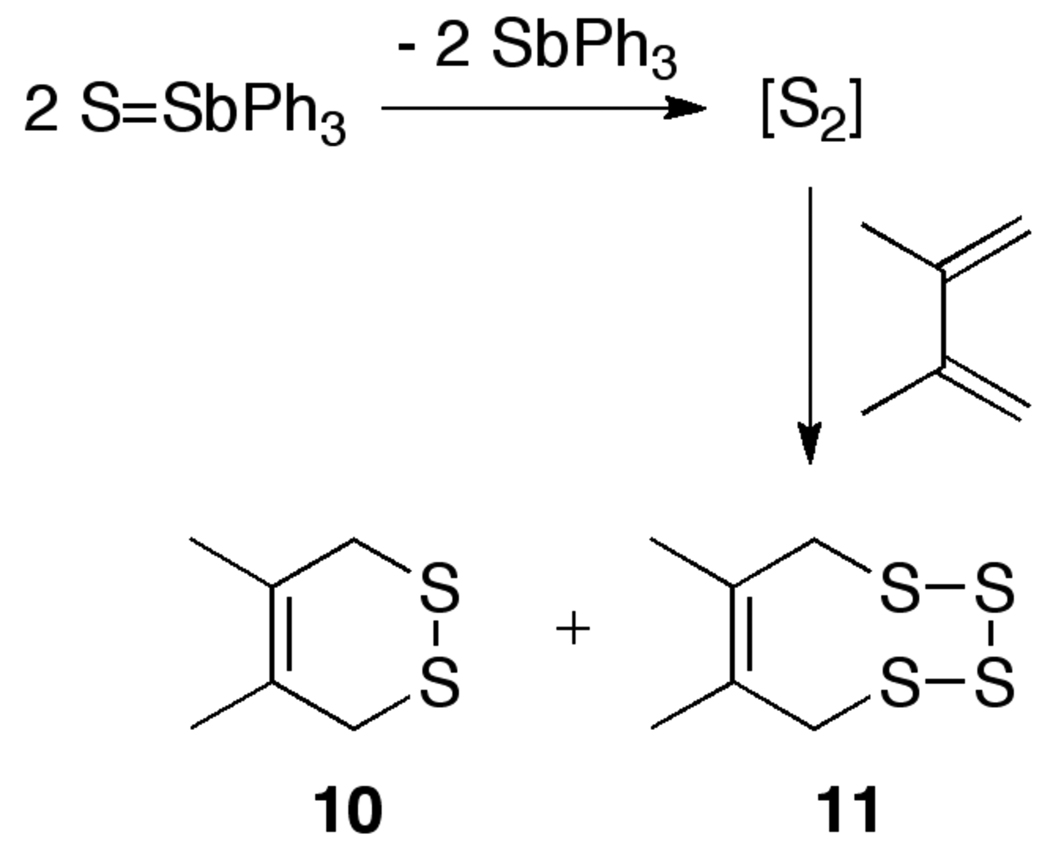

We also considered the possibility that the reactions of 1–3 to form the disulfido-dicopper(II) complexes 4–6 might involve decomposition of S=SbPh3 to S2.9a This decomposition was reported to occur in CS2 via a second-order process with a rate constant of 0.014(2) M−1s−1 at 35 °C, with the release of S2 suggested by the formation of cyclic sulfides 10 and 11 when 2,3-dimethylbutadiene was used as a trapping reagent (Scheme 3). We found that mixtures of S=SbPh3 (4.7 mM) and 2,3-dimethylbutadiene (20 equiv.) in CD2Cl2 at 20 °C were unchanged after ~3 d, with no evidence for formation of 10 or 11. In a second experiment, 1H NMR spectroscopic monitoring of a mixture of 1 and 2,3-dimethylbutadiene (20 equiv.) revealed slow generation of 10 and loss of 1 via a first-order process with a rate constant equal to 1.4(4) × 10−5 s−1 (t1/2 = ~14 h). There was no evidence for the presence of the disulfido-dicopper(II) complex 4 during this process. Interestingly, under identical conditions 4 also decayed in the presence of 2,3-dimethylbutadience to yield 10. This reaction of 4 is characterized by a first-order rate constant of 1.7(3) × 10−4 s−1, corresponding to a rate approximately 10 times faster than that of the reaction of 1 to yield 10. The rate of decay of 1 to yield 10 in the presence of 2,3-dimethylbutadiene is similar to that observed for the decay of 1 to 4 in its absence, suggesting that S2 formation cannot be ruled out in the pathways of both reactions. However, these reactions are significantly slower than that for the reaction of 1 with [(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 to give 4 and 7. On this basis and in view of the kinetic data described above, it appears unlikely that S2 formation is important in the reaction of 1 with [(Me3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6.

Scheme 3.

Decay of S=SbPh3 to S2 as determined by trapping with 2,3-dimethylbutadiene.

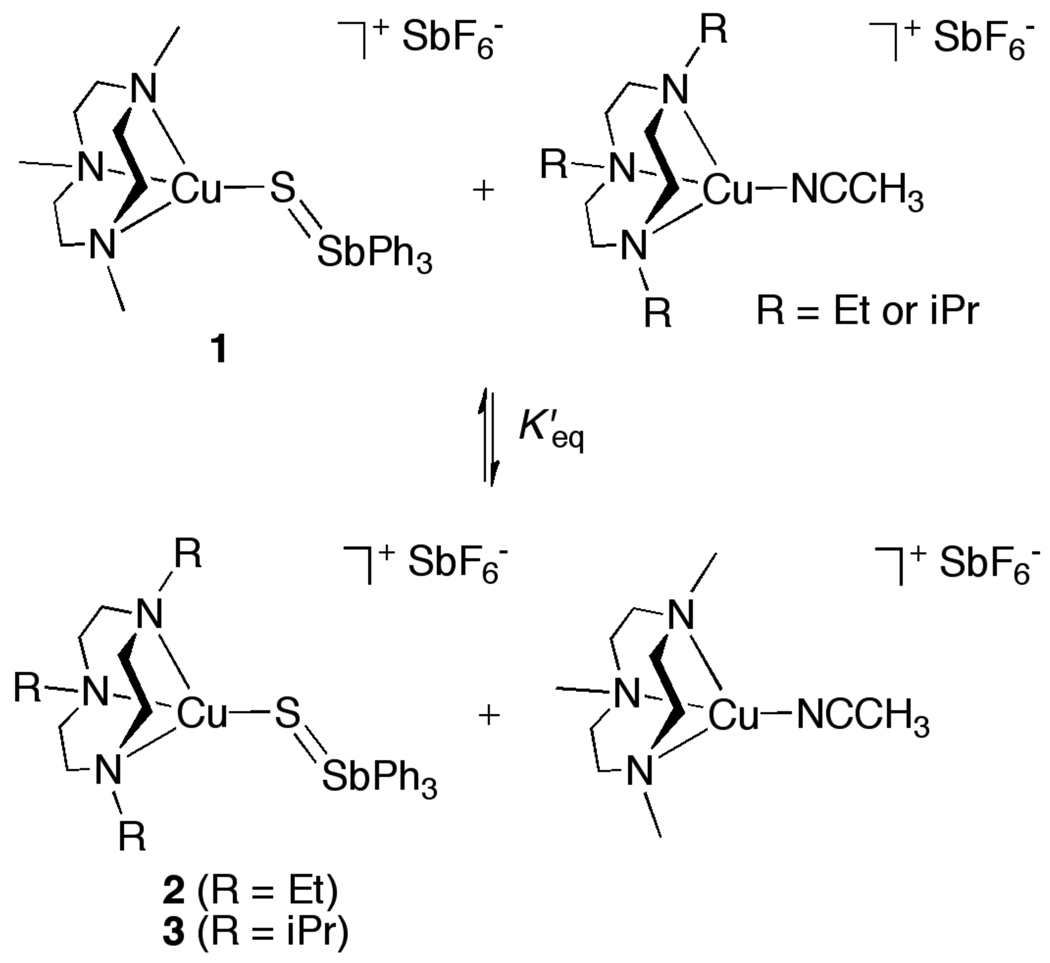

This latter reaction is further complicated by exchange of the S=SbPh3 unit between the Cu(I) centers. This exchange was identified by 1H NMR spectroscopy and ESI-MS analysis of the reaction of 1 with [(R3tacn)Cu(CH3CN)]SbF6 (R = Et or iPr). Shortly after mixing, the 1H NMR spectrum showed peaks due to all four species in the equilibrium shown in Scheme 4. From the relative integrations after equilibrium was reached (~10 min), K’eq values of 0.41 (R = Et) or 0.054 (R = iPr) were measured. These results were corroborated by ESI-MS (Figure S8), where parent ion peak envelopes for the cationic portions of 1 and 2 (R = Et, ~1:1 ratio) or 1 and 3 (R = iPr, ~6:1 ratio) were observed immediately after mixing of the respective reagents. The trend in K’eq values correlates inversely with the degree of steric interactions between the ligand substituents and the bound S=SbPh3 moiety (K’eq decreases as the steric interactions increase, R = Et < iPr). Importantly, equilibration is rapid relative to the decay to the disulfido-dicopper(II) complexes, and thus occurs prior to the suggested pathway for the decay reaction shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 4.

Equilibration of Cu(I)-S=SbPh3 and Cu(I)-NCCH3 complexes.

Reaction of S=SbPh3 with [(TMCHD)Cu(NCCH3)]PF6

In contrast to the reactions with the Cu(I) complexes of R3tacn ligands that led to isolable Cu(I)-S=SbPh3 adducts, no such adducts were identified when the Cu(I) complex of the bidentate diamine TMCHD was treated with S=SbPh3. Instead, the known tricopper cluster [(TMCHD)3Cu3(S)2](PF6)3 (12) was isolated cleanly in good yield (79%). This procedure for the synthesis of 12 is superior to that previously reported involving use of S8,8a facilitating advanced spectroscopic studies of the cluster aimed at addressing contentious bonding and oxidation state issues.8 Presumably, an initial Cu(I)-S=SbPh3 adduct forms in the reaction, but due to its lower coordination number is more prone to oligomerization than the analogs supported by the tridentate R3tacn ligands.

Summary and Conclusions

In explorations ultimately aimed at preparing copper-sulfur complexes to model the active site of nitrous oxide reductase, we have found that Ph3Sb=S forms stable adducts [(R3tacn)Cu(S=SbPh3)]SbF6 (1–3), the first examples of which have been structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography. These adducts undergo slow decay in solution to form [(R3tacn)2Cu2(µ-η2:η2-S2)]2+ species (4–6) and SbPh3. Conversion to 4–6 is accelerated by addition of [(R3tacn)Cu(NCCH3)]SbF6 to 1–3, and yield [(R3tacn)Cu(SbPh3)]SbF6 (7–9) as coproduct instead of free SbPh3. Mechanistic studies of this reaction revealed rapid exchange of Ph3Sb=S between the Cu(I) sites and pre-equilibrium formation of a dicopper intermediate. We speculate that the dicopper intermediate contains a bridging Ph3Sb=S moiety and that the rate-controlling step in the reaction involves loss of Ph3Sb from that intermediate. Subsequent more rapid events that ultimately result in [Cu2(µ-η2:η2-S2)]2+ core formation remain unclear. Reaction of [(TMCHD)Cu(CH3CN)]PF6 with S=SbPh3 did not lead to an observable adduct, and instead led to the known tricopper cluster [(TMCHD)3Cu3(µ3-S)2](PF6)3 in good yield. Overall, the results demonstrate the utility of Ph3Sb=S for delivering sulfur to Cu(I) centers supported by N-donor ligands, cleanly yielding thermodynamically stable [Cu2(µ-η2:η2-S2)]2+ and [Cu3S2]3+ cores.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (R37 GM47365 to W.B.T.) for financial support of this research and Victor G. Young, Jr., for assistance with the X-ray crystallography.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Illustrative experimental procedures, spectra, and kinetics results, and representions of the X-ray crystal structures of complexes 2 and 3 (PDF); X-ray structural data (CIFs). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Zumft WG, Kroneck PMH. Adv. Microb. Phys. 2007;52:107–227. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(06)52003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Brown K, Tegoni M, Prudêncio M, Pereira AS, Besson S, Moura JJ, Moura I, Cambillau C. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:191–195. doi: 10.1038/73288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown K, Djinovic-Carugo K, Haltia T, Cabrito I, Saraste M, Moura JJ, Moura I, Tegoni M, Cambillau C. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41133–41136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Paraskevopoulos K, Antonyuk SV, Sawers RG, Eady RR, Hasnain SS. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;362:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Rasmussen T, Berks BC, Sanders-Loehr J, Dooley DM, Zumft WG, Thomson AJ. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12753–12756. doi: 10.1021/bi001811i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen P, Cabrito I, Moura JJG, Moura I, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10497–10507. doi: 10.1021/ja0205028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Alvarez ML, Ai J, Zumft W, Sanders-Loehr J, Dooley DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:576–587. doi: 10.1021/ja994322i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ghosh S, Gorelsky SI, DeBeer George S, Chan JM, Cabrito I, Dooley DM, Moura JJG, Moura I, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3955–3965. doi: 10.1021/ja068059e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Oganesyan VS, Rasmussen T, Fairhurst S, Thomson AJ. Dalton Trans. 2004:996–1002. doi: 10.1039/b313913a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chen P, Gorelsky SI, Ghosh S, Solomon EI. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4132–4140. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Solomon EI, Sarangi R, Woertink JS, Augustine AJ, Yoon J, Ghosh S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:581–591. doi: 10.1021/ar600060t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. York JT, Bar-Nahum I, Tolman WB. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2008;361:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2007.06.047. and references cited therein.

- 6.Bar-Nahum I, Gupta AK, Huber SM, Ertem MZ, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2812–2814. doi: 10.1021/ja808917k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sarangi R, York JT, Helton ME, Fujisawa K, Karlin KD, Tolman WB, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:676–686. doi: 10.1021/ja0762745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen P, Fujisawa K, Helton ME, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6394–6408. doi: 10.1021/ja0214678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Brown EC, York JT, Antholine WE, Ruiz E, Alvarez S, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13752–13753. doi: 10.1021/ja053971t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mealli C, Ienco A, Poduska A, Hoffmann R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2864–2868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Alvarez S, Hoffmann R, Mealli C. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:8358–8373. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Berry JF. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:2719–2724. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Jason ME. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:2641–2646. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baechler RD, Stack M, Stevenson K, Vanvalkenburgh V. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon. 1990;48:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Bauer A, Capps KB, Wixmerten B, Abboud KA, Hoff CD. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:2136–2142. doi: 10.1021/ic981221x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zuo J-L, Zhou H-C, Holm RH. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:4624–4631. doi: 10.1021/ic0301369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Groysman S, Holm RH. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:4090–4102. doi: 10.1021/ic062441a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Groysman S, Wang J-J, Tagore R, Lee SC, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12794–12807. doi: 10.1021/ja804000k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue JP. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4747–4783. doi: 10.1021/cr050044w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capps KB, Wixmerten B, Bauer A, Hoff C. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2861–2864. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lobana TS. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 1989;37:495–588. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bar-Nahum I, York JT, Young VG, Jr, Tolman WB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:533–536. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.See Supporting Information.

- 16.(a) Haselhorst G, Stoetzel S, Strassburger A, Walz W, Wieghardt K, Nuber B. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1993:83–90. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cahoy J, Holland PL, Tolman WB. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:2161–2168. doi: 10.1021/ic990095+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahapatra S, Halfen JA, Wilkinson EC, Pan G, Wang X, Young VG, Jr, Cramer CJ, Que L, Jr, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:11555–11574. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahadevan V, Hou Z, Cole AP, Root DE, Lal TK, Solomon EI, Stack TDP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11996–11997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Transition metal complexes of S=SbPh3 have been reported, although none have been characterized structurally by X-ray crystallography: King MG, McQuillan GP. J. Chem. Soc. (A) 1967:898–901. ; (b) Kuhn N, Schumann H. J. Organomet. Chem. 1986;304:181–193. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hieber W, John P. Chem. Ber. 1970;103:2161–2177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Powell D, Houser R. Dalton Trans. 2007:955–964. doi: 10.1039/b617136b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Lam BMT, Halfen JA, Young VG, Jr, Hagadorn JR, Holland PL, Lledós A, Cucurull-Sánchez L, Novoa JJ, Alvarez S, Tolman WB. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:4059–4072. doi: 10.1021/ic000248p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Halfen JA, Young VG, Jr, Tolman WB. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2102–2103. doi: 10.1021/ic971216d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Halfen JA, Mahapatra S, Wilkinson EC, Gengenbach AJ, Young VG, Jr, Que L, Jr, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:763–776. [Google Scholar]; (d) Halfen JA, Mahapatra S, Olmstead MM, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:2173–2174. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ohrenberg C, Liable-Sands LM, Rheingold AL, Riordan CG. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:4276–4283. doi: 10.1021/ic010273a. and references cited therein.

- 23. Melzer MM, Li E, Warren TH. Chem. Commun. 2009:5847–5849. doi: 10.1039/b911643e. and references cited therein.

- 24.Reigle R, Casadonte D, Bott S. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 1994;24:769–773. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Weller F, Dehnicke K. Naturwissenschaften. 1981;68:523–524. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pebler J, Weller F, Dehnicke K. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1982;492:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown EC, Bar-Nahum I, York JT, Aboelella NW, Tolman WB. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:486–496. doi: 10.1021/ic061589r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, van RijnJ, Verschoor GC. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984:1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.