Abstract

Objective

Many healthcare organizations (HCOs) including Kaiser Permanente, Johns Hopkins, Cleveland Medical Center, and MD Anderson Cancer Center, provide access to online health communities as part of their overall patient support services. The key objective in establishing and running these online health communities is to offer empathic support to patients. Patients' perceived empathy is considered to be critical in patient recovery, specifically, by enhancing patient's compliance with treatment protocols and the pace of healing. Most online health communities are characterized by two main functions: informational support and social support. This study examines the relative impact of these two distinct functions—that is, as an information seeking forum and as a social support forum—on patients' perceived empathy in online health communities.

Design

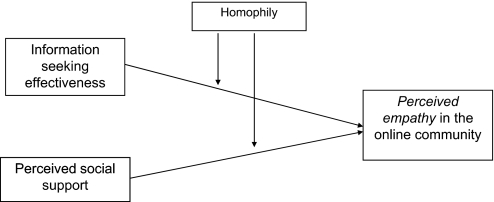

This study tests the impact of two variables that reflect the above functions of online health communities—information seeking effectiveness and perceived social support—on perceived empathy. The model also incorporates the potential moderating effect of homophily on these relationships.

Measurements

A web-based survey was used to collect data from members of the online health communities provided by three major healthcare centers. A regression technique was used to analyze the data to test the hypotheses.

Results

The study finds that it is the information seeking effectiveness rather than the social support which affects patient's perceived empathy in online health communities run by HCOs. The results indicate that HCOs that provide online health communities for their patients need to focus more on developing tools that will make information seeking more effective and efficient.

Keywords: Health informatics, machine learning, health information seeking, online, health communities, consumer health informatics, internet and health

Introduction

Consumer health information seeking through online health communities has been the focus of considerable attention as the number of patients relying on online health information has steadily increased.1–6 In the last few years the number of online health communities has increased rapidly as more patients seek to access alternate sources of health information as well as to connect with other patients with the same or similar disease. The large number of such communities is a testament to their popularity among health consumers.2 This has prompted many healthcare organizations (HCOs) including Kaiser Permanente, Johns Hopkins, etc, to provide access to online communities to their patients as part of their overall patient support services. A key gratification for patients from online communities is perceived empathy7–11 (ie, the empathy perceived by patients in an online health community based on their interactions and discourse with others). Perceived empathy has the potential to directly affect the success of the treatment and the healing process.12 13 Further, perceived empathy from online communities could supplement caregiver provided empathy, which is expensive and time consuming.

Despite its potential importance, there has been limited effort to conceptualize and measure perceived empathy. It is also not clear from previous studies what factors lead to or determine perceived empathy for members in online health communities. While patients' perceived empathy can be a critical outcome of online communities, online communities are often considered to have two major functions—as an information seeking forum and as a social support forum.14–19

This study aims to conceptualize and measure patients' perceived empathy in online health communities and to examine its key antecedents, specifically patients'/consumers' information seeking effectiveness and perceived social support.

At the same time, it is also important to consider the potential role of homophily as it has been suggested in previous research to be a key ingredient for the effective functioning of online health communities.20 21 Homophily is defined as the degree to which individuals are congruent or similar in certain attributes, such as demographic variables, beliefs, and values, etc.20

Here, we examine whether homophily moderates the impact of both information support and social support on perceived empathy. The study uses data collected through a web-based questionnaire survey from the members of online health communities provided by three academic health centers—the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins, MD Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas, and the Joslin Diabetes Center affiliated with Harvard Medical School.

Research model

Perceived empathy in online health communities

Patients' perceived empathy has been considered an important factor when providing care and it has been shown to have a direct impact on health outcomes.22–24 Healthcare professionals are routinely trained to show empathy towards their patients as it can have a direct impact on patients' satisfaction with the care as well as on their compliance with treatment procedures.25 26 Perceived empathy has also been found to expedite the healing process and is considered to be a key ingredient in the holistic, relationship-centered care of the bio-psycho-social model of primary care.23 24 It has also been found that empathic concern was greater among people who had the same or similar life experiences and life events.27 An interesting finding by Hodges et al27 was that perceived empathy was higher if the subjects knew that the people communicating with them had prior knowledge of the subjects' life experiences. This finding assumes importance in the context of online health communities as patients (health consumers) usually narrate their experiences in their queries and other members who respond to such queries typically have read those postings.

However, studies carried out in online communities did not evaluate whether patients actually perceived empathy during their interactions in the community. Many concentrated on mere discourse analysis to examine whether empathy was communicated.8 9 28 29 Further, the studies were not focused specifically on conceptualizing or measuring patient's perceived empathy. It is important to conceptualize and measure perceived empathy since, as noted earlier, empathic experience received from these communities is considered to be one of the main outcomes of patient interactions in these online health communities with direct impact on healing and other health outcomes.7–11

As such, a key objective of the current study is to define and measure perceived empathy in online health communities. Perceived empathy can be felt in an online community when one posts a query and gets responses from other community members. Perceived empathy can also be felt when reading through the discourse in an online community. Thus, it also involves one's perception while reading other members' messages when the messages are sympathetic, compassionate, sincere, sensitive, heart-felt, tolerant, and supportive. Hence, here perceived empathy is defined as an individual member's (ie, patient's) perception regarding other members' feelings of compassion, warmth, sincerity, and sensitiveness towards oneself and towards the problems one has narrated or posted in the online health community.

Effectiveness of health information seeking in online communities

Informational support or health information seeking in online health communities has been found to affect healthcare consumers' decision making.2 14 The effectiveness of this information seeking has also been found to affect their information competence and participation in healthcare.14 30 However, the impact of information seeking on emotional gratification such as perceived empathy has not yet received much research attention. Here we contend that the success of such information seeking or the extent of information seeking effectiveness is a critical antecedent to patients' perceived empathy in the online health community.

Hypothesis H1: Consumers' information seeking effectiveness in an online health community will be positively associated with their perceived empathy.

Perceived social support

In general, in the offline health context, social support has been associated with many health benefits including reduction of stress, minimizing the possibility of depression, and strengthening of the immune system.31 These benefits from social support, although not empirically proven, are considered to be some of the most critical benefits of online health communities.32 33

During chronic/terminal illnesses, people turn to online health communities specifically to interact with people who are in a similar situation and thereby receive empathy.8 10 11 In many cases, patients have reported that they receive much more understanding (or empathy) from the people in these communities than from their offline social network such as family members, friends, and coworkers.34 Empathy is perceived only when the patient perceives that others in the community have had similar experiences as well as an understanding of the situation the patient is going through. Social support in an online health community can lead to perceived empathy since members of such communities usually have either personal experience or indirect experience (through their family members and friends) of the disease.35 36

Hypothesis H2: Consumers' perceived social support in an online health community will be positively associated with their perceived empathy.

Homophily

According to the theory of homophily,37 most human communication will occur between a source and a receiver who are alike. Homophily with the people around one has been found to be a factor that makes people more comfortable in any given situation.38 In the context of online support groups, homophily has been found to enhance members' satisfaction with their interactions in the group.39 However, more importantly, in offline contexts, it has been found that patient's perceived empathy is greater when people with the same or similar life experiences and life events communicated with them and when such people shared their experiences about particular events.27

Sharing of experiences about diseases and treatment protocols is one of the key aspects of any online health community discourse. Thus here we argue that when patients perceive homophily with other patients, it likely enhances the impact of both information seeking effectiveness and social support on perceived empathy. It has been suggested that patients' learning and processing of health information is enhanced when such information is acquired from people who are like themselves or have similar disease experience.6 Thus, in the current context, when a patient perceives greater homophily with other members with whom they interact, they are also likely to be more efficient at processing and absorbing the information acquired from others, in turn, leading to higher perceived empathy. Similarly, when a patient perceives homophily with other members, the value of the supportive communication with those members also increases, in turn, leading to higher perceived empathy. Thus, we conclude that at higher levels of homophily, the impact of both information seeking effectiveness and perceived social support on perceived empathy is stronger (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

Hypothesis H3: Consumers' perceived homophily with the members in an online health community will positively moderate the impact of information seeking effectiveness on perceived empathy, such that the higher the homophily, the stronger will be the impact of information seeking effectiveness on perceived empathy.

Hypothesis H4: Consumers' perceived homophily with the members in an online health community will positively moderate the impact of perceived social support on perceived empathy, such that higher the homophily, the stronger will be the impact of perceived social support on perceived empathy.

Method

Study design

Data were collected from members of three online health communities run by three major medical centers in the USA (the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins, MD Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas, and Joslin Diabetes Center affiliated with Harvard Medical School). The selection criteria required that the community should be an online patient community owned and run by an HCO and that it should allow open (public) access. Open access communities have more interactions than closed access communities and as such offer more data. In all three communities, the nature of the consumer interactions was similar—patients posted queries related to a particular disease or treatment and these queries were answered by peer healthcare consumers who had had experiences with the same disease/treatment (either direct experience or indirect experience through their loved ones).

A web-based questionnaire survey was used to collect data from the members of the three online communities. The respondents were sent emails inviting them to participate in the survey. The email included a link to the survey website. The respondents were people who had interacted in that online community in the previous month. The email addresses of these online community members were taken from their postings in the community. Approximately 800 consumers who had interacted in the above three online communities in the month before study commencement were identified. These respondents were sent emails inviting them to participate in the survey. Overall, 215 responses were received for an overall response rate of 26.8%. However, 32 incomplete responses had to be excluded, leaving a final set of 183 responses for data analysis.

Study measures

The study measures for perceived empathy were developed specifically for this study; the other measures were previously validated scales or adapted from previously validated scales.

Perceived empathy

To date, empathy research has been highly focused on measuring an individual's empathy towards others. For example, several instruments have been developed such as the Barrett-Lennard Relation Inventory40 for measuring nurses' empathy, the Davis41 Interpersonal Reactivity Index for measuring an individual's empathy, and the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy42 for measuring physicians' empathy. All of these are self-reported scales that only measure a person's capability for feeling empathy towards others.

Here perceived empathy reflects a patient's perception of other members' empathy towards him/her. Recent studies have developed scales to measure patients' perceived empathy from their physicians12 and from their nurses.13 There are no scales that measure perceived empathy in an online community. Hence, a new scale was developed for this study to specifically measure perceived empathy in an online health community.

The scale was developed based on our earlier definition of perceived empathy in the context of an online community. It was designed to measure compassion and sympathy perceived during interactions in the online community. Mere expressions of compassion and sympathy will not be perceived as empathy if the receiver does not perceive sincerity, understanding, warmth, and supportiveness in the message.27A semantic differential scale was developed, which had eight items: unsympathetic/sympathetic, not compassionate/compassionate, insensitive/sensitive, not heart-felt/heart-felt, cold/warm, sincere/insincere, tolerant/intolerant, and supportive/not supportive. The items were administered using a 7-point semantic differential scale. An exploratory factor analysis (principal component) using Varimax rotation was performed with eigenvalues >1 which extracted a single factor for perceived empathy. Table 1 lists the factor loadings for this scale. The scale had a reliability score of α=0.95.

Table 1.

Summary of measures and item loadings

| Construct | Items (item loading) |

| Perceived empathy (7-point semantic differential scale) | |

| During my interactions in the online community, I felt the community to be | |

| Unsympathetic/sympathetic | 0.890 |

| Sincere/insincere | 0.847 |

| Not compassionate/compassionate | 0.839 |

| Not heart-felt/heart-felt | 0.821 |

| Tolerant/intolerant | 0.816 |

| Insensitive/sensitive | 0.811 |

| Cold/warm | 0.776 |

| Supportive/not supportive | 0.616 |

| Information seeking effectiveness (7-point Likert-type scale) | |

| I obtain information that is readily usable | 0.920 |

| I obtain information that is credible | 0.906 |

| I obtain information that is relevant | 0.905 |

| I obtain information that is reliable | 0.897 |

| I obtain information in a timely manner | 0.886 |

| Perceived social support (7-point Likert-type scale) | |

| I could count on my friends in the discussion board when things went wrong | 0.904 |

| I had friends in the discussion board with whom I could share my joys and sorrows | 0.903 |

| I got the emotional help and support I needed from the discussion board | 0.901 |

| I could talk about my problems with the members in the discussion board | 0.890 |

| I knew someone in the discussion board who was a real source of comfort to me | 0.885 |

| Homophily (7-point semantic differential scale) | |

| Members in this community | |

| Behave like me/do not behave like me | 0.907 |

| Think like me/don't think like me | 0.854 |

| Have a health situation similar to mine/have a health situation different from mine | 0.851 |

| Are from a social class similar to mine/are from a social class different from mine | 0.846 |

| Are unlike me/are like me | 0.792 |

| Have a health background different from mine/have a health background similar to mine | 0.745 |

Effective information seeking

Effectiveness of information seeking was measured using a previously validated scale for measuring information search effectiveness in online communities.43 44 The scale had five items that reflect the effectiveness of the information that customers obtain from the online community. The items were administered using a 7-point Likert-type scale. A factor analysis (principal component) using Varimax rotation was performed with eigenvalues >1 which extracted a single factor for effectiveness of information seeking. Table 1 lists the factor loadings for this scale. The scale had a reliability score of α=0.94.

Perceived social support

This scale was adapted from an existing multidimensional scale developed specifically for measuring perceived social support.45 The scale was adapted to fit the context of online health communities. The scale had five items presented using a 7-point Likert-type scale. A factor analysis (principal component) using Varimax rotation was performed with eigenvalues >1 which extracted a single factor for perceived social support. The items and the factor loadings are given in table 1. The scale had a reliability score of α=0.94.

Homophily

Homophily with community members was measured by adapting an existing scale.46 A factor analysis (principal component) using Varimax rotation was performed with eigenvalues >1 which extracted a single factor for homophily. Six items were chosen after factor analysis. The items were administered using a 7-point semantic differential scale. The items and the factor loadings are given in table 1. This measure was found to have a reliability of α=0.91.

Data analysis

A majority of the respondents (41%) were 50–60 years old. The subjects were mostly female (70%). With regard to educational background, 37% of the respondents had an undergraduate degree, 27% had a master's degree, and 26% had completed high school. The respondents were more or less equally distributed among the four income levels specified: 27% had an income of $100 000 or above; 11% had an income between $80 000 and $100 000; 26% had an income between $50 000 and $80 000; and 25% had an income of less than $50 000. The majority of the respondents (65%) had been members of one of the three online health communities for more than 1 year.

Correlations among the study variables can be found in table 2. The reliability coefficient (α) for the various measures ranged from 0.81 to 0.95, exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.70 set by Fornell and Larcker47 (see table 2). Thus, all the constructs demonstrated good internal consistency. To check for discriminant validity, a pair-wise correlation test was conducted among all study items. We found that the correlations between items belonging to different constructs were all below 0.2, thereby demonstrating the discriminant validity of the measures. Another indicator of discriminant validity is when the variance extracted for each construct is higher than the squared correlation between the constructs.47 This was evaluated for each pair of constructs in the model; we found that all constructs satisfied this criterion, thus providing further evidence of the discriminant validity of the measures used.

Table 2.

Correlations, means, SD, and reliability (α)

| Variables | Mean | SD | α Coefficient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Perceived empathy | 5.8 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 1 | |||

| 2. Information seeking | 5.6 | 1.4 | 0.94 | 0.473* | 1 | ||

| 3. Perceived social support | 4.6 | 1.86 | 0.94 | 0.215* | 0.372* | 1 | |

| 4. Homophily | 5.0 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 0.274* | 0.173† | 0.247* | 1 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Regression analysis was conducted to test the study hypotheses. The analysis also incorporated a dummy variable (termed ‘HCO’) to control for the effect of the HCO that was running the online community (eg, the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins, MD Anderson Cancer Center, or Joslin Diabetes Center). To test the interaction effect of homophily, two product variables were created: homophily and information seeking effectiveness; and homophily and perceived social support. These two products were included in regression analysis along with the other independent variables.

Before conducting the regression analyses, the data were tested for normality assumptions. Specifically, the Shapiro-Wilk W test was carried out on the data for each of the study constructs, which indicated that the test statistic W was not significant in each of those cases; thus, the normality assumption was found to hold for the study data.

Results

The results of the simple regression can be found in table 3. As predicted hypothesis, H1 was supported—information seeking effectiveness had a significant positive impact on perceived empathy (β=0.426, p<0.001). However, H2 was not supported—perceived social support did not have any impact on perceived empathy. Hypothesis H3 was supported—information seeking effectiveness moderated by homophily had a significant positive impact on perceived empathy (β=0.705, p<0.05). However, hypothesis H4 was not supported—perceived social support moderated by homophily did not have any impact on perceived empathy. Even though perceived social support was highly correlated with perceived empathy, this factor was not a predictor of perceived empathy. Homophily with members had a significant positive impact on perceived empathy (β=0.23, p<0.005).

Table 3.

Regression results (n=183)

| Variables | Perceived empathy | |||||

| β Coefficient | SE | p Value | β Coefficient | SE | p Value | |

| Constant | 2.76 | 0.076 | 0.151 | 0.900 | 0.546 | 0.425 |

| HCO (control variable) | 0.138 | 0.076 | 0.056 | 0.133 | 0.077 | 0.153 |

| Information seeking | 0.426 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.907 | 0.194 | 0.002 |

| Social support | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.654 | 0.057 | 0.158 | 0.850 |

| Homophily | 0.231 | 0.058 | 0.001 | 0.669 | 0.217 | 0.009 |

| Information seeking×homophily | 0.705 | 0.037 | 0.040 | |||

| Social support×homophily | 0.033 | 0.029 | 0.928 | |||

| R2 | 0.278 | 0.293 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.262 | 0.268 | ||||

HCO, healthcare organization.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the study sample was taken from online communities run by HCOs—the Department of Pathology at Johns Hopkins, MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Joslin Diabetes Center. These are highly reputable and large HCOs, which might limit the generalizability of the study findings to online communities run by lesser known and smaller HCOs. Second, the data were collected from open access communities. Whether a closed access community has more focus on social relationships than information seeking is an issue for future research in this area. Third, the sample included only those members who had publicized their emails in these online communities. This is a constraint for all studies that attempt to collect data from publicly accessible online communities; however, it also implies a potential sample bias and as such a study limitation here. While we acknowledge this potential limitation, we have also found that members who publicize their email addresses are likely to be repeat visitors (compared to those who do not publicize their email addresses) and, as such, form the most appropriate study subjects for the current study. Finally, the usable response rate was only 23%, although this is greater than the average 10% response rate in previous web-based surveys.48–50 One of the challenges with this kind of data collection is that email addresses found in public online communities can be outdated or inactive.48 Non-response due to technical factors, lack of interest, and/or boredom is considered quite common in web-based surveys.48 51 52 In addition, in this study, participation was voluntary and there were no incentives for completing the surveys. Nonetheless, the sample size is quite similar to those of other studies that have collected data from community members through web-based questionnaires.53

Discussion and implications

The findings from this study indicate that it is through information seeking effectiveness—rather than through social support—that patients perceive empathy in HCO-run online health communities. This suggests that HCOs running online health communities should focus on the information sharing and exchange component of their online communities.

Many organizations that provide online communities (eg, the ‘patients like me’ community54) seem to have understood the importance of this factor and have started to provide users with tools to effectively search and extract the information they need as well as interpret and process the information. For example, in the ‘patients like me’ community, online community members are provided with tools that allow them to compile diverse types of information about community members, such as information on the medications used for treatment and statistics on the different medications used by members. This information is often displayed graphically, which makes it easier for members to find and absorb.55 By acknowledging online health communities as important repositories of information, HCOs can focus on developing tools that allow community members to seek out information that is relevant and useful, thereby enhancing members' experience of perceived empathy.

HCOs can also create information-rich environments by incorporating key design features into their online communities that enhance patients' information seeking effectiveness. Some of the design features that can be incorporated are content rating systems, knowledge centers, clean technical designs, and flow technologies. Rating systems that allow patients to rate the usefulness of responses not only improve the quality of responses but also allow other patients (who are ‘lurkers’56) to gauge more accurately the value of each response. In addition, results of informatics research on information seeking in static websites may be adaptable to the online community context. Keselman et al describe ways to help lay people seek health information effectively from static websites, including providing query formulation support tools, suggestions of alternative terms to make the query more specific, guides to facilitate the search process, and consumer friendly terminology linked to professional terminology.57 Some of these could be adapted to the online community context. Providing links to other information support sites from the online community can also improve the knowledge of all the community members, including understanding of complex medical terminology, and contribute to patient education, without significant additional investment by HCOs. This could also improve the consumers' ‘flow’ in the online community. Flow is defined as a state of consciousness where the user gets completely immersed in the activity and reaches a superior level of performance in that activity.58 Using designs that improve consumers' ‘flow’ in a computer mediated environment has been found to produce positive attitudes and positive experiences for the users.59

HCOs can also create knowledge centers that compile responses and present users with links to additional knowledge in that area which can aid patient education as well as improve knowledge sharing activities, although this may require allocation of additional HCO resources to the online communities. More activity in the community may not only improve the quality and quantity of knowledge available but also enhance the patient experience and learning in the community.40

The study findings also emphasize the importance of ‘homophily’ in an online health community, particularly its role in contributing to patient's perceived empathy via its moderating effect. Design features that enable community members to connect with other members with a similar health background would help them to perceive higher levels of homophily in their interactions. In this regard, HCOs may find it valuable to look at social networking sites such as Facebook60 and LinkedIn61 as a potential source of design features that could improve their online communities.

The lack of support for hypothesis H2 (ie, regarding the impact of social support) could be due to the characteristics of the study context. While, in general, social support is an important component of online health communities, patients who visit online health communities run by an HCO may view these communities as an extension of their relationship with the HCO, rather than primarily as a means of gaining support from peers. Specifically, patients may regard HCOs as repositories of information and may believe that the online health communities run by those organizations are likely to be forums for information exchange (rather than social networking). This suggests that factors such as ownership and the reputation and purpose of the managing organization could affect the perceived function of online health communities and how and why community members interact in them.

Future studies of online health communities run by non-HCOs (as well as those run by patients themselves) may yield different results. We suspect that in other contexts, social support may have a positive association with perceived empathy (although whether such effects are stronger than those of information seeking would need to be investigated). The finding from this study does not mean that HCOs should forego their focus on enhancing social relationships in these communities. Enhancing social relationships could further enhance the ‘empathic experience’ in the HCO-run communities.

Finally, the study findings indicate that informatics researchers should acknowledge the importance of online health communities as a venue for health information seeking as well as for social and emotional support, and incorporate both aspects into future studies. There are a number of information seeking questions worthy of future study in the context of online communities. For example, how do patients complement the information acquired from online communities? Are there ways in which online communities could enable them to better integrate information from other online and offline sources? Does the manner in which information is provided in the online community impact the effectiveness of information seeking? Further, is the reception and retention of information acquired from online health communities higher than that from static health websites?

To date, health information seeking studies have primarily focused on static websites such as Medline and on search engines.57 62 There has not been much focus on patients' information seeking patterns and behaviors in online health communities. In an online community, consumers could be searching for personalized information that would either supplement or reinforce the information that they have already received from other sources.6 They could be looking for ‘experiential’ information.6 This type of information seeking has not been properly explored in the informatics literature. More studies in this area would enhance our understanding of how information seeking effectiveness can be improved in online communities.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University at Albany, SUNY (protocol number 08-066).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cotton SR, Gupta SS. Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1795–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jadad AR, Enkin MW, Glouberman S, et al. Are virtual communities good for our Health. BMJ 2006;332:925–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkelman WJ, Choo CW. Provider-sponsored virtual communities for chronic patients: improving health outcomes through organizational patient-centered knowledge management. Health Expect 2003;6:352–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurent MR, Vickers TJ. Seeking health information online: Does Wikipedia matter? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:471–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran JA, Murphy AL, Abidi SS, et al. Bridging the gap: knowledge seeking and sharing in a virtual community of emergency practice. Eval Health Prof 2009;32:312–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Grady LA, Witteman H, Wathen CN. The experiential health information processing model: supporting collaborative web-based patient education. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preece J, Ghozati K. Observations and explorations of empathy online. In: Rice RR, Katz JE, eds. The Internet and Health Communication: Experience and Expectations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc, 2001:237–60 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preece J. Empathic communities: balancing emotional and factual communication. Interact Comput 1999;12:63–7 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamberg L. Online empathy for mood disorders: patients turn to internet support groups. JAMA 2003;289:3073–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn J. An exploration of helping processes in an online self-help group focusing on issues of disability. Health Soc Work 1999;24:220–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malik SH, Coulson NS. Coping with infertility online: an examination of self-help mechanisms in an online infertility support group. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:315–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof 2004;27:237–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson JK. Relationships between nurse-expressed empathy, patient-perceived empathy and patient distress. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;27:317–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Hawkins R. Computer-based support systems for women with breast cancer. J Am Med Assoc 1999;281:1268–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, et al. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups:systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ 2004;328:1166–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan PF, Ripich S. Use of a home-care computer network by persons with AIDS. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1994;10:258–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coulson NS, Buchanan H, Aubeeluck A. Social support in cyberspace: a content analysis of communication within a Huntington's disease online support group. Patient Educ Couns 2007;68:173–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinert C, Whitney AL, Hill W. Chronically ill rural women's view of health care. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care 2005;5:38–52 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gooden RJ, Winefield HR. Breast and prostate cancer online discussion boards: a thematic analysis of gender differences and similarities. J Health Psychol 2007;12:103–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Touhey JC. Situated identities, attitude similarity, and interpersonal attraction. Sociometry 1974;37:363–74 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Walther JB, Pingree S, et al. Health information, credibility, homophily, and influence via the Internet: Web sites versus discussion groups. Health Commun 2008;23:358–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price S, Mercer S, MacPherson H. Practitioner empathy, patient enablement and health outcomes: a prospective study of acupuncture patients. Patient Educ Couns 2006;63:239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rakel DP, Hoeft TJ, Barrett BP, et al. Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Fam Med 2009;41:494–501 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novack DH. Realizing Engel's vision: psychosomatic medicine and the education of physician-healers. Psychosom Med 2003;65:925–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro J, Morrison EH, Boker JR. Teaching empathy to first year medical students: evaluation of an elective literature and medicine course. Educ Health(Abingdon) 2004;17:73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comstock LM, Hooper EM, Goodwin JM, et al. Physician behaviors that correlate with patient satisfaction. J Med Educ 1982;57:105–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges SD, Klein KJK, Veach D, et al. Giving birth to empathy: the effects of similar experience on empathic accuracy, empathic concern, and perceived empathy. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2010;36:398–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeil U. Social support in empathic online communities for older people. In People and Computers XXI: HCI.but not as we know it. Proceedings of the 21st British HCI Group Annual Conference on HCI. UK: British Computer Society, 2008;Volume 2:255–6 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng J, Lazar J, Preece J. Empathic and predictable communication influences online interpersonal trust. Behav Inf Technol 2004;23:97–106 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Inter Med 2001;16:435–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dean A, Lin N. The stress buffering role of social support: problems and prospects for systemic investigation. J Health Soc Behav 1977;32:321–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaudoin CE, Tao CC. Benefiting from social capital in online support groups: an empirical study of cancer patients. CyberPsychol behav 2007;10:587–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen S, Syme SL. Social support and health. New York: Academic Press, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rheingold H. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uchino B, Cacioppo J, Kiecolt-Glaser J. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull 1996;119:488–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trobst KK, Collins RL, Embree JJ. The role of emotion in social support provision: gender, empathy, and expressions of distress. J Soc Pers Relat 1994;11:45–62 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lazarsfeld P, Merton RK. Friendship as a social Process: a substantive and methodological analysis. In: Berger M, Abel T, Page CH, eds. Freedom and Control in Modern Society. New York: Van Nostrand, 1954:18–66 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Infante D, Rancer A, Womack D. Building Communication Theory. 3rd edn Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright KB. The communication of social support within an on-line community for older adults: a qualitative analysis of the SeniorNet community. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication 2000;1:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett-Lennard GT. Empathy cycle: refinement of a nuclear concept. J Couns Psychol 1981;28:91–9 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;44:113–26 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas 2001;61:349–66 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nambisan P, Watt JH. Online Community Experience (OCE) and its impact on customer attitudes: an exploratory study. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing 2008;2:150–75 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nambisan P. Conceptualizing Customers' Online Community Experience (OCE): an experimental study. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising 2009;5:309–28 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988;52:30–41 [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCroskey JC, Richmond VP, Daly JA. The development of a measure of perceived homophily in interpersonal communication. Hum Commun Res 1975;1:323–32 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fornell C, Larker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res.1981;18:39–50 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watt JH. Internet systems for evaluation research. In: Gay G, Bennington TL, eds. Information Technologies in Evaluation: Social, Moral, Epistemological, and Practical Implications. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999:23–44 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Couper MP, Traugott MW, Lamias MJ. Web survey design and administration. Pub Opinion Quart 2001;65:230–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solomon DJ. Conducting Web-based surveys. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2001;7 Retrieved from the Web on January 8, 2010. http://pareonline.net/genpare.asp?wh=4&abt=Solomon [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dillman DA, Bowker DK. The Web questionnaire challenge to survey methodologists. 2001. Retrieved from the Web on January 8, 2010. http://survey.sesrc.wsu.edu/dillman/zuma_paper_dillman_bowker.pdf

- 52.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Methods. 2nd edn New York: Wiley, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanis M. Health-related on-line forums: what's the big attraction? J Health Commun 2008;13:698–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.http://www.patientslikeme.com

- 55.Frost JH, Massagli MP. Social uses of personal health information within PatientsLikeMe, and online patient community: What can happen when patients have access to one another's data. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preece J, Nonnecke B, Andrews D. The top five reasons for lurking: improving community experiences for everyone. Comput Human Behav 2004;20:201–23 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keselman A, Browne AC, Kaufman DR. Consumer health information seeking as hypothesis testing. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:484–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: HarperCollins, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Novak TP, Hoffman DL, Yung YF. Measuring the customer experience in online environments: a structural modeling approach. Marketing Science 2000;19:22–42 [Google Scholar]

- 60.http://www.facebook.com

- 61.http://www.linkedln.com

- 62.Lau AY, Coiera EW. Do people experience cognitive biases while searching for information? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:599–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]