Abstract

The authors investigated use of the internet-based patient portal, kp.org, among a well-characterized population of adults with diabetes in Northern California. Among 14 102 diverse patients, 5671 (40%) requested a password for the patient portal. Of these, 4311 (76%) activated their accounts, and 3922 (69%), logged on to the patient portal one or more times; 2990 (53%) participants viewed laboratory results, 2132 (38%) requested medication refills, 2093 (37%) sent email messages, and 835 (15%) made medical appointments. After adjustment for age, gender, race/ethnicity, immigration status, educational attainment, and employment status, compared to non-Hispanic Caucasians, African–Americans and Latinos had higher odds of never logging on (OR 2.6 (2.3 to 2.9); OR 2.3 (1.9 to 2.6)), as did those without an educational degree (OR compared to college graduates, 2.3 (1.9 to 2.7)). Those most at risk for poor diabetes outcomes may fall further behind as health systems increasingly rely on the internet and limit current modes of access and communication.

Introduction

Internet-based patient portals enable patients to make appointments, view laboratory results, refill medications, and communicate with their physician, pharmacist, or nurse1–4 online, and emerging evidence suggests that using them may improve healthcare quality.5 For those with a chronic illness such as diabetes, patient portals can provide a vehicle to receive ongoing self-management support.3 6

Health-services research has revealed social disparities in diabetes outcomes by race/ethnicity and education.7 Some have attributed widening diabetes disparities8 to lower rates of uptake of advances in diabetes care by more vulnerable groups, and/or by the practitioners and settings that disproportionately care for them.9 The same populations subject to disparities in diabetes health outcomes are also more likely to lack access to information technology, a phenomenon known as the ‘digital divide.’10 11 Beyond this divide in internet access, only a limited body of research work has explored reported acceptance12 13 and use of internet-based patient portals for health across race/ethnicity.14–16

Examining whether social factors influence engagement with internet patient portals in diabetes has clinical and public health relevance. Therefore, we examined patient use patterns of an innovative internet-based patient portal within a well-characterized, large, diverse cohort of adult, medically insured patients with diabetes cared for in an integrated delivery system in the USA.

Case description: the internet patient portal ‘kp.org’

The secure patient portal, for all members, includes key features such as laboratory test results with interpretation and secure provider messaging. It also permits the clinical transactions of refilling medications and making medical appointments. In order to use the system, participants first had to use an internet-connected computer to request a password for the secure website (kp.org). After participants signed in once using a one-time default password, they were prompted to change their password, ‘activating’ their accounts. Once accounts are active, participants can ‘log on’ with their own passwords. KPNC does not offer computer or internet training for members, but internal staff are trained to help users who call for assistance.

Method of implementation

Study population

The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE, available at http://distancesurvey.org/) enrolled an ethnically stratified, random sample of patients from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) Diabetes Registry.17 KPNC is an integrated healthcare delivery system that provides comprehensive medical care to over 3 million members (30% of the entire Northern California population). Except for the extremes of income, the demographic characteristics of KPNC's patient population are similar to those of the overall population of Northern California.18

The survey methods and cohort profile have been described previously.17 The survey had a 62% response rate, yielding 20 188 respondents. For this analysis, we included only respondents who reported speaking and reading in English, having adequate vision (not legally blind), and being enrolled in KPNC throughout the study period, from January 1 to December 31, 2006. We obtained data on usage of the internet-based patient portal from the electronic member database. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Kaiser Foundation Research Institute and University of California San Francisco.

Measures

We examined which participants requested a password for the members-only website (kp.org), the proportion who activated their accounts by changing their default password, and the proportion who ‘logged on’ with their own user-generated password. Completion of the critical ‘logging on’ step then enabled the participant to perform several actions, including viewing laboratory test results, emailing their physicians or care team, requesting medication refills, and making appointments. The primary exposures of interest included self-reported race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and immigration status (born outside vs inside the US).

Analyses

First, we determined the frequency of requesting a password for the patient portal, activation of accounts, log-ons to accounts, and use of individual health-services functions. We report the proportion of participants who completed the password request and activation steps. For log-ons and individual functions, we report the proportion who used the requisite function one or more times, versus those who never used that particular function. Second, we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the independent associations of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment to the outcome of logging on to the internet-based patient portal. However, in an attempt to differentiate between social disparities in use based on internet/computer access versus navigation, we separately performed the same analysis restricting to participants who requested a password for the patient portal and thus can be assumed to have some internet access. We accounted for design effects (stratified random sampling) throughout by applying expansion weights (reciprocal of the non-proportional sampling fractions (by race) to multivariate models).

Under the assumption that patient portals are intended to improve clinical outcomes, any improvements would require engaging patients with moderate to poor disease control. To examine whether there were any differences in use based on clinical indicators, we performed an exploratory analysis comparing the diabetes and cardiovascular intermediate outcomes of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c>9%), systolic blood pressure (SBP>130 mm Hg), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL>130 mg/dl) between those who did versus those who did not log on to the portal.

Example and observations

The 14 102 participants were ethnically diverse with varying educational attainment (table 1). During the 12-month study period, 5671 (40%) requested a password via the internet for the patient portal. Among these, whom we assume had sufficient access to the internet by virtue of request for a password for the patient portal, we observed a decrement in each step of the use process, 1360 (25%) did not activate their accounts using the mailed, default password, and an additional 389 (7%) never logged on to the patient portal using their own passwords (figure 1). Three thousand nine hundred and twenty-two logged on. Although each user could use multiple functions, among those who requested a password, 2990 participants (53%) viewed their laboratory results, 2132 (38%) requested prescription medication refills, 2093 (37%) sent email messages to their physicians/care team, and 835 (15%) made medical appointments using the internet-based patient portal.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N=14 102)

| Characteristic | N (%) or mean (SD) |

| Age (years) | |

| 30–39 | 578 (4) |

| 40–49 | 2065 (15) |

| 50–59 | 4604 (33) |

| 60–69 | 4519 (32) |

| 70 and above | 2336 (17) |

| Employment status | |

| Currently employed | 6464 (55) |

| Retired | 3976 (34) |

| Unemployed | 220 (2) |

| Disabled/poor health | 752 (6) |

| Student | 19 (0) |

| Homemaker/parent/care giver | 288 (2) |

| Female | 6885 (49) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African–American | 2899 (21) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3957 (28) |

| Latino | 1923 (14) |

| Asian American | 1253 (9) |

| Filipino | 1624 (12) |

| Other/mixed | 2446 (17) |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 10.1 (9) |

| Born outside the USA | 3408 (24) |

| Educational attainment | |

| No degree | 1397 (10) |

| High school degree or test-equivalent | 4099 (30) |

| Some college | 3739 (27) |

| College graduate/postgraduate | 4581 (33) |

Figure 1.

Proportion of users who requested a password who used each function one or more times during the study period (N=5671).

There were marked race/ethnic differences in use (figure 2A), with African–American (31%), Latino (34%), and Filipino (32%) participants least likely, and Asian (53%) and White (51%) participants most likely to both request a password for the internet-based patient portal (a marker for internet access and intent to use) and log on to the portal after requesting a password was completed (an early marker for navigability once access is obtained).

Figure 2.

(A) Proportion who requested a password and logged on to the internet-based patient portal, by race/ethnicity (for difference across ethnicities, p<0.01) and immigration (for difference by immigration status p=0.51) status (N=14 102). (B) Proportion who requested a password and logged on to the internet-based patient portal, by educational attainment (N=14 102). *For differences by educational attainment, p<0.01.

For example, 2006 (51%) of Caucasians compared to 887 (31%) of African–Americans requested a password for the patient portal. Of those who requested a password, 395 (21%) of Latinos logged on to the patient portal compared to 1496 (38%) of Caucasians. Moreover, we observed a consistent gradient with respect to educational attainment, such that those with higher educational attainment were more likely to both request a password and log on to the internet-based patient portal (figure 2B). We did not see any differences in patient portal use by immigration status (figure 2A).

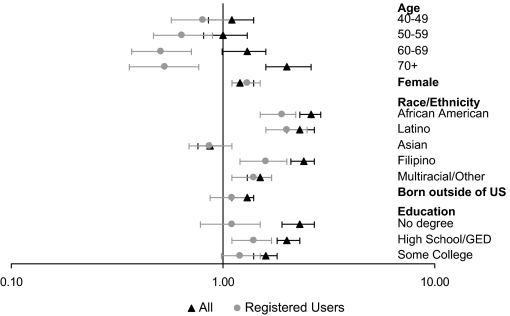

In analyses adjusted for age, sex, educational attainment, employment, immigration status, and race/ethnicity, we found that race/ethnicity and educational attainment were independently associated with logging on to the patient portal (figure 3). Compared to non-Hispanic Caucasians, African–American and Latino participants were more likely not to have ever logged on to the patient portal (AOR 2.6 and 2.3, respectively). This disparity persisted when we restricted the analysis to users that requested a password.

Figure 3.

ORs for not logging on to patient portal. GED, General Educational Development Test.

Compared to those with a college degree, those with a lower educational attainment were more likely to never have logged on. However, when we examined users who requested a password only, the strength of this pattern was attenuated and, with the exception of the comparison between high school and college graduates, became non-significant. Importantly, age over 70 years was associated with lack of use among the entire cohort; however, among users who requested a password, older subjects were more likely to log on to the patient portal compared to those under 40 (figure 3). When we examined use of the individual functions (lab results view, emails, appointments, medication refills), we found the relationships between race/ethnicity and educational attainment to be remarkably consistent with logging on and across all user functions (see appendix 1 and table 2 available online at www.jamia.org).

Finally, compared to those who used the patient portal, non-users were more likely to have suboptimal control of their diabetes and related risk factors, as demonstrated by a higher proportion with HbA1c>9% (17% vs 14%, p<0.01), SBP>130 mm Hg (50% vs 46%, p<0.01), and LDL>130 mg/dl (20% vs 18%, p<0.01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to examine actual use of an internet-based patient portal offered as a routine part of care by a population of patients with diabetes, a chronic disease with significant self-management demands. Older adults, those with less educational attainment, and certain racial/ethnic minority groups (African–Americans, Latinos, and Filipinos) were less likely than younger, more educated, and White, non-Latinos to request a password to use the patient portal, suggesting that problems with internet access, or differences in acceptance of internet patient portal use, may contribute to social disparities in use. However, among those with access and apparent intent to use (eg, those who requested a password), these same ethnic minority groups and those with lower educational attainment were less likely to employ the individual functions offered by the portal. Notably, among those who had sufficient computer access to request a password for the patient portal, older adults were more likely to log on than younger users, perhaps because of increased healthcare and self-management needs.

There are a number of potential mechanisms to explain our findings. First, participant and social constraints, such as lack of internet access and training, inadequate social support, competing time demands, limited literacy, and e-health literacy,19 may all influence use of an internet-based patient portal. Second, the patient portal design may demand better navigation skills than some participants have. Third, although KP promotes it aggressively, targeted dissemination via ethnic media and other means may be needed to reach racial/ethnic minorities and those with limited education attainment. Fourth, provision of internet and computer training would be expected to increase patient portal use, since there was a significant drop-off in use, even after requesting a password.

Study strengths include a large, diverse population with uniform access to care, and detailed real-world assessments of use of an internet-based patient portal. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, because KP has a more robust patient portal than most other US healthcare delivery settings, results may not generalize to the uninsured or other healthcare settings. However, as internet-based patient portals become more widely available in the USA and abroad, these issues will emerge in other settings. Second, because the patient portal is available only in English, we excluded non-English speakers. Third, we did not directly measure participants' computer access, although an internal survey of KPNC members suggests that 90% of members aged 25–64 and 50% of members aged 65–79 have internet/computer access.20 As another proxy for access, we inferred that those who requested a password on-line had at least some level of access to the internet. Fourth, our explanatory analysis of indicators of diabetes control was intended to examine the reach of the patient portal, not to suggest any causal association between diabetes control and use of an internet patient portal.

Lessons learned

We observed pervasive racial/ethnic and educational disparities in use of a patient portal. Moreover, racial disparities in particular appear to extend beyond limitations in access to computer/internet. As services migrate to the internet, those most at risk for poor diabetes health outcomes are at risk of falling further behind as health systems increasingly rely on patient portal health service functions and limit the alternative modes of access and communication. The internet has potential to use visuals/spoken/multilingual techniques to enhance comprehensibility of healthcare and health promotion, but barriers to internet-based healthcare services require attention to disadvantaged groups and tailoring of services as well as expanded computer/internet access. Further research should include explicit study of the barriers to subsequent use among those who request a password but do not actually use the patient portal, as well as study of the impact of portal use on chronic disease health outcomes.

Footnotes

Funding: Funds were provided by National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases R01 DK65664 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development R01 HD046113. This work was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources (KL2 RR024130). US is supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality K08 HS017594. DS is supported by a grant from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R18 HS01726101, an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award ULRR024131.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the institutional review boards at Kaiser Foundation Research Institute and University of California San Francisco.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mulvaney SA, Rothman RL, Wallston KA, et al. An internet-based program to improve self-management in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:602–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong N, Powell J. Preliminary test of an Internet-based diabetes self-management tool. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:114–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RW, Wald JS, Poon EG, et al. Design and implementation of a web-based patient portal linked to an ambulatory care electronic health record: patient gateway for diabetes collaborative care. Diabetes Technol Ther 2006;8:576–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn JS, Aulakh V, Bosworth A. What it takes: characteristics of the ideal personal health record. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:369–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou YY, Kanter MH, Wang JJ, et al. Improved quality at Kaiser Permanente through e-mail between physicians and patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1370–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, et al. Individualized electronic decision support and reminders to improve diabetes care in the community: COMPETE II randomized trial. CMAJ 2009;181:37–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilder RP. Education and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2008 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2009. AHRQ Pub. No. 09-0002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health 2008;98:216–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: At A Glance Fact sheet Diabetes Successes and oppurtunities for population-based prevention and control. 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/AAG/pdf/diabetes.pdf (accessed 25 Jan 2010).

- 11.NHS Diabetes Health inequalities and diabetes. 2010. http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/our_work_areas/inequalities/ (accessed 26 Jan 2010).

- 12.Samal L, Hutton HE, Erbelding EJ, et al. Digital divide: variation in internet and cellular phone use among women attending an urban sexually transmitted infections clinic. J Urban Health 2010;87:122–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkar U, Piette JD, Gonzales R, et al. Preferences for self-management support: findings from a survey of diabetes patients in safety-net health systems. Patient Educ Couns 2008;70:102–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang BL, Bakken S, Brown SS, et al. Bridging the digital divide: reaching vulnerable populations. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:448–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roblin DW, Houston TK, 2nd, Allison JJ, et al. Disparities in use of a personal health record in a managed care organization. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:683–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu J, Huang J, Kinsman J, et al. Use of e-Health services between 1999 and 2002: a growing digital divide. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:164–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffet HH, Adler N, Schillinger D, et al. Cohort Profile: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE)—objectives and design of a survey follow-up study of social health disparities in a managed care population. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:38–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health 1992;82:703–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine Health Literacy, eHealth, and Communication Putting The Consumer First Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon NP. Readiness of Seniors in Kaiser Permanente's Northern California Region to Use New Information Technologies for Health Care-Related Communications: The HUNT Study. Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente, 2009 [Google Scholar]