Abstract

Objective

Research has examined various aspects of the validity of the research criteria for binge eating disorder (BED) but has yet to evaluate the utility of the five DSM-IV “indicators for impaired control” specified to help determine loss of control while overeating (i.e., binge eating). We examined the diagnostic efficiency of these indicators proposed as part of the research criteria for BED (eating until uncomfortably full, eating when not hungry, eating more rapidly than usual, eating in secret, and feeling disgust, shame, or depression after the episode).

Method

916 community volunteers completed a battery of measures including questions about each of the indicators. Participants were categorized into three groups: BED (N=164), bulimia nervosa (BN; N=83), and non-binge-eating controls (N=669). Four conditional probabilities (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive power [PPP], and negative predictive power [NPP]) as well as total predictive value (TPV) and kappa coefficients were calculated for each indicator criterion in separate analyses comparing BED, BN, and combined BED+BN groups relative to controls.

Results

PPPs and NPPs suggest all of the indicators have predictive value, with eating alone because embarrassed (PPP=.80) and feeling disgusted (NPP=.93) performing as the best inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively. The best overall indicators for correctly identifying binge eating (based on TPV and kappa) were eating when not hungry and eating alone because embarrassed.

Conclusions

All five proposed “indicators for impaired control” for determining binge eating have utility and the diagnostic efficiency statistics provide guidance for clinicians and the DSM-5 regarding their usefulness for inclusion or exclusion.

Keywords: binge eating, DSM-5, diagnostic efficiency, binge eating disorder

Since the inclusion of binge eating disorder (BED) in Appendix B of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) as a research criteria set in need of further study, numerous studies have provided empirical support for various aspects of the validity of this diagnostic construct (e.g., (Grilo et al., 2008; Grilo, Masheb, & White, 2010). In their critical review of the literature, Striegel-Moore and Franko (2008) concluded that sufficient empirical evidence exists supporting BED as a distinct and formal diagnosis in the DSM-5.

BED is defined by recurrent binge eating without inappropriate weight-control behaviors that characterize bulimia nervosa (BN). Binge eating is defined as overeating large quantities of food during which a subjective loss of control is experienced. The research criteria include a set of five “indicators of impaired control” provided with the goal of assisting in the determination of whether loss of control during overeating (i.e., binge eating) exists. These indicators were originally generated by experts based on clinical experience, but they have yet to be empirically evaluated or validated. In preparation for the DSM-5, various groups have examined aspects of the research criteria for BED (Striegel-Moore & Franko, 2008) including for example the frequency and duration stipulation requirements for binge eating (Wilson & Sysko, 2009). However, no studies have been reported testing the diagnostic utility of the proposed “indicators of impaired control.” Currently, the DSM-IV research criteria set for BED, but not for BN, requires the presence of at least 3 of 5 “indicators of impaired control”: eating until uncomfortably full, eating when not hungry, eating more rapidly than usual, eating in secret, and feeling disgust, guilt, or depression after the episode.

Diagnostic efficiency refers to the extent to which diagnostic criteria are able to discriminate persons with a given diagnosis from those without that diagnosis, as determined by the application of conditional probabilities (Grilo, Becker, Anez, & McGlashan, 2004; Grilo, McGlashan et al., 2001). Such analyses can be particularly relevant to the refinement or revision of criterion sets in classification or diagnostic schemes such as the DSM. The use of diagnostic efficiency has contributed to the refinement of some behavioral and diagnostic constructs (e.g., (Faraone, Biederman, Sprich-Buckminster, Chen, & Tsuang, 1993; Grilo et al., 2004; Milich, Widiger, & Landau, 1987; Waldman & Lilienfeld, 1991)), and such data previously influenced, to some degree, some DSM–IV Work Groups (Gunderson, Zanarini, & Kisiel, 1991). Such analyses also have considerable practical application for clinicians in terms of assisting them during evaluations and diagnostic decision making.

The present study examined the diagnostic efficiency of the “indicators for impaired control” proposed as part of the research criteria for BED in the DSM-IV. We used the internet to recruit participants for an on-line survey rather than a treatment-seeking or clinic-based sample. The survey included direct questions for each of the indicators and these criteria were examined in three diagnostic groups (BED, BN, and combined BED+BN). The three diagnostic groups were created using convergent data from established assessment measures for eating disorder psychopathology. Diagnostic efficiency statistics were calculated for the indicators separately for the BED, BN, and BN+BED groups; these analyses involved relevant data from “controls” comprising non-binge-eating and non-purging participants.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 916 community volunteers drawn from a larger series of 1298 respondents to online advertisements seeking volunteers aged 18 years or older for a research study about eating and dieting. These participants were selected from the larger sample based on criteria (described below) used to define our three eating disorder diagnostic groups (BED, BN, and BED+BN) and control group. Advertisements containing a link to an external web survey were placed on Craigslist internet classified ads in different United States cities (e.g., Los Angeles, Washington DC, San Antonio, Philadelphia, Boston, Baton Rouge, Tulsa, Austin, Oklahoma City, Seattle, San Francisco) and on Google banners. The advertisement appeared as a Google banner when users entered keywords: “weight gain; body image; binge eating; compulsive eating; obesity; obesity epidemic; obesity test; obesity studies; obesity quiz; weight questionnaire; weight quiz; weight studies; eating test; eating questionnaire.” The sample was 12.8% male (n=117) and 86.9% female (n=796); a total of n=3 participants did not report gender. The racial/ethnic distribution for the study sample was: 79.8% Caucasian, 5.6% Hispanic, 5.1% African American, 5.8% Asian, and 3.7% reporting “other” or missing.

Procedures

Participants completed self-report questionnaires through the secure online data gathering website SurveyMonkey, a research-based web server with secure 128-data encryption. Participants were required to provide informed consent prior to completing the measures. No personal identifying information was collected. The study was approved by the Yale institutional review board.

Assessments and Measures

Participants provided basic demographic information, self-reported height and current weight, and completed a battery of self-report measures.

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire

(EDE-Q) (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994) is the self-report version of the Eating Disorder Examination interview (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) and assesses eating disorders and their features. The EDE-Q focuses on the past 28 days and assesses the frequency of different forms of overeating behaviors, including objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; defined as feeling a loss of control while eating unusually large quantities of food) and various inappropriate weight control methods (self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, etc.). The EDE-Q also comprises four subscales: dietary restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern. The EDE-Q has received psychometric support, including good test-retest reliability (Reas, Grilo, & Masheb, 2006) and convergence with the Eating Disorder Examination interview in studies with diverse disordered-eating groups (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001a, 2001b; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen, & Beumont, 2004; Wilfley, Schwartz, Spurrell, & Fairburn, 1997) and has especially good reliability for assessing purging behaviors (Mond, Hay, Rodgers, & Owen, 2007; Mond et al., 2004).

Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Patterns -- Revised

(QEWP-R; (Yanovski, 1993)) assesses a number of current and historical eating/weight variables. The QEWP-R, which was used in DSM-IV field trials, assesses each of the diagnostic criteria for BED and BN. The QEWP-R has received psychometric support for certain aspects of its validity (Brody, Walsh, & Devlin, 1994; Nangle, Johnson, Carr-Nangle, & Engler, 1994) including concordance with the EDE-Q in determining binge eating and BED (Celio, Wilfley, Crow, Mitchell, & Walsh, 2004; Elder et al., 2006).

Indicator Items

A series of questions was constructed to evaluate the DSM-IV “indicators for impaired control” items. In the QEWP-R questionnaire, the DSM-IV indicators of impaired control are evaluated only when individuals have endorsed overeating unusually large amounts of food while experiencing a loss of control; i.e., individuals who deny binge eating are instructed to “skip out” of those items specifically evaluating the indicators. In the current questionnaire, no skip outs were used. Participants responded to the general question “Do you have the following experiences when eating?” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Never” to “Always.” Specific experiences were: 1) Eating much more rapidly than usual? 2) Eating until you feel uncomfortably full? 3) Eating large amounts of food even though you are not physically hungry? 4) Eating alone because you are embarrassed by how much you were eating? 5) Feeling disgusted with yourself, depressed, or feeling very guilty after eating? In the current study, responses of “often” and “always” were considered to represent the presence of the symptom. The responses “never,” “rarely,” and “sometimes” were considered negative.1

Classification of Study Groups

Participants were classified according to binge eating status based on their responses on the EDE-Q and QEWP-R. To be classified as either BED or BN, an individual must have reported binge eating (i.e., “eating an unusually large amount of food” and “a sense of having lost control over eating”) at least four times over the previous four weeks. This once-weekly frequency stipulation follows the current proposal for the DSM-5 by the Eating Disorder Workgroup. In addition, participants classified as BED and BN also needed to respond affirmatively to the QEWP-R item evaluating binge eating (i.e., eating within any two-hour period what most people would regard as an unusually large amount of food). Individuals classified as BN also reported purging (i.e., self induced vomiting, laxative, or diuretic use as a means of controlling shape or weight) at least four times over the previous four weeks, as well as undue influence of body shape and/or weight in self evaluation (i.e., a score of “moderate importance” or greater on EDE-Q items). Participants classified as BED reported no purging behaviors in the previous four weeks. Participants reporting less frequent (i.e., less than weekly) binge eating and/or purging were excluded from analysis; therefore the non-binge-eating control group consisted of individuals who reported zero binge eating and purging episodes during the previous 28 days. A total of 1298 participants completed the EDE-Q and reported height and weight information yielding a BMI≥18.5. Of these, n=916 were included in the primary analyses. A total of 267 participants were excluded due to reporting infrequent binge or purge episodes (i.e., less than once weekly); 18 participants were excluded for skipping the binge and/or purge items on the EDE-Q. An additional 64 were excluded for reporting purge behaviors in the absence of binge eating, and 24 were excluded for denying binge eating on the QEWP-R item evaluating binge eating. The final sample, therefore, consisted of individuals with BMI≥18.5, who completed all key items on the EDE-Q and who qualified for BED or BN diagnosis based on responses on key items from the EDE-Q and QEWP-R. The control group consisted of individuals who denied binge eating and purging during the previous 28 days on the EDE-Q and QEWP-R.

Statistical Analysis

To examine the validity of the classification scheme (i.e., the diagnostic criterion groups), BED, BN, and control groups were compared on demographic and eating disorder variables using chi-square and ANOVA. Base rates and diagnostic efficiency efficacy statistics (Faraone et al., 1993; Grilo et al., 2004) were calculated for the DSM-IV indicator items for the BED and BN groups – separately and in combination – utilizing the control group data. We also explored the diagnostic efficiency indices separately by gender and using different diagnostic threshold levels (i.e., once versus twice weekly frequency criteria, in light of emerging research for DSM-5 (Wilson & Sysko, 2009)).

First, four types of conditional probabilities were calculated. Sensitivity (SENS), or true-positive rate, refers to likelihood of the feature being present given the presence of the diagnosis. Specificity (SPEC), or true-negative rate, refers to the likelihood of the feature being absent given the absence of the diagnosis. Positive Predictive Power (PPP) refers to whether the presence of the feature accurately predicts the presence of the diagnosis (i.e., utility as an inclusion criterion). Negative Predictive Power (NPP) refers to whether the absence of that feature accurately predicts the absence of the diagnosis (i.e., utility as an exclusion criterion). Since diagnosticians are generally more interested in the likelihood of a diagnosis of a disorder given the presence or absence of a feature, PPP and NPP, respectively, are more useful than knowing the likelihood of a feature being present given the patient has or does not have a diagnosis (i.e., SENS and SPEC, respectively). Whereas sensitivity and specificity are independent of diagnosis base rate, PPP and NPP vary with diagnosis base rates (Faraone et al., 1993; Grilo et al., 1994). In general, PPP increases whereas NPP decreases with increasing diagnosis base rates (Baldessarini, Finklestein, & Arana, 1983; Finn, 1982; Meehl & Rosen, 1955).

In addition to the four conditional probabilities, we calculated Total Predictive Value (TPV), a measure of percentage agreement, which serves as an overall index of the indicator’s utility for correctly predicting the diagnosis (Faraone et al., 1993; Grilo et al., 2004). Lastly, we calculated a Kappa coefficient (Cohen, 1960), which corrects for chance agreement, for each indicator.

ANOVAs were used to test for diagnostic group differences in the reported frequency of each of the indicator items. As a conservative test, we performed a second set of ANOVAs on re-categorized groups using the twice-weekly (i.e., the DSM-IV) frequency criterion for binge eating and purging. Finally, we generated receiver operating characteristic curves to examine the optimal number of indicators required to accurately predict the presence of binge eating.

Results

Overall, 27% (n=247) of participants endorsed binge eating at a frequency of at least once per week. The overall base rate of BED was 18% (n=164) and the base rate of BN was 9% (n=83). The remaining 73% (n=669) denied any binge eating or purging during the previous 28 day period. The distribution of binge eating did not differ significantly as a function of gender or race. The mean BMI was 29.2 (SD=8.3) kg/m2; approximately 39.7% of the sample reported a BMI in the normal range (18.5<BMI<25 kg/m2), 23.5% reported a BMI in the overweight range (25≤BMI<30) and 36.8% of the sample reported a BMI in the obese range (BMI≥30).

Table 1 summarizes demographic and eating disorder variables separately for the study groups. The BED group reported significantly higher BMI than the BN and control groups, who did not differ significantly from each other. Study groups differed on key eating disorder variables, including binge eating and purging frequencies in the past 28 days, supporting the validity of our categorization. The study groups differed on all EDE-Q subscales and global score, with the BN group reporting greater disturbance than the BED group, who in turn reported greater disturbance than the control group.

Table 1.

Comparisons of BN, BED and Control groups on demography, BMI, and eating disorder variables

| BED (n=164) |

BN (n=83) |

Controls (n=669) |

Test statistic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | df | χ2 | p | ||

| Sex (Female) | 140 | 85.9 | 77 | 91.6 | 590 | 87.0 | 2, n=913 | 1.70 | .43 | |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | df | F | p | η2 | |

| Age | 36.96 | 12.01 | 33.94 | 11.38 | 34.38 | 12.87 | 2, 794 | 2.536 | .08 | 0.006 |

| BMIa, b | 32.57 | 9.08 | 28.78 | 8.22 | 28.45 | 7.96 | 2, 913 | 16.762 | <.001 | 0.035 |

| EDE-Q Binge eating episodesa, b, c | 9.57 | 7.05 | 14.05 | 13.68 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2, 913 | 452.307 | <.001 | 0.498 |

| EDE-Q Purging episodesb, c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 20.78 | 21.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2, 913 | 403.005 | <.001 | 0.469 |

| EDE-Q Restrainta, b, c | 2.42 | 1.56 | 4.08 | 1.31 | 1.90 | 1.51 | 2, 913 | 79.538 | <.001 | 0.148 |

| EDE-Q Eating Concernsa, b, c | 3.01 | 1.43 | 4.16 | 1.24 | 1.08 | 1.13 | 2, 913 | 362.414 | <.001 | 0.443 |

| EDE-Q Shape Concernsa, b, c | 4.74 | 1.08 | 5.42 | 0.66 | 3.09 | 1.67 | 2, 913 | 145.691 | <.001 | 0.242 |

| EDE-Q Weight Concernsa, b, c | 4.03 | 1.09 | 4.78 | 0.87 | 2.57 | 1.48 | 2, 913 | 147.869 | <.001 | 0.245 |

| EDE-Q Totala, b, c | 3.55 | 1.04 | 4.61 | 0.78 | 2.16 | 1.24 | 2, 913 | 223.421 | <.001 | 0.329 |

Note. BN and BED classification was determined by binge eating and/or purging at a frequency of once per week or more for the previous 28 days.

Note. Post-hoc Scheffe tests found:

significant difference between BED and Controls at p < 0.01 level

significant difference between BED and BN at p < 0.01 level

significant difference between BN and Controls at p < 0.01 level

Table 2 shows the base rates and diagnostic efficiency indices for the indicator items for impaired control in the BED and BN groups separately, as well as when combined (i.e., classified together into a single “binge eating” group). In each analysis, the comparison group consisted of individuals who denied any binge eating or purging in the previous 28 days. The most commonly reported indicator item was feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty after binge episodes, while the least frequently reported indicator was eating alone because of embarrassment. The positive predictive power (PPP) of each indicator item was lower when examining the BN group alone, which would be expected due to the lower base rate of the disorder (.09) as compared to the base rate of BED (.18). Examining the combined BED+BN group, the PPP values indicated that all of the indicator items have some predictive value in the diagnosis of binge eating. The NPP values were somewhat higher and range from .82 (eating rapidly) to .93 (feeling disgusted) in the combined group. Taking both PPP and NPP into consideration, the TPVs indicate that eating large amounts when not physically hungry and eating alone because embarrassed have the highest utility in identifying binge eating within the BED and BN groups individually as well as when combined.

Table 2.

Base rates and diagnostic efficiency indices for DSM-IV behavioral criteria for binge eating analyzed separately for BED (N=164), BN (N=83), and BED+BN (N=247) groups.

| Variable Criterion | BR | Sens | Spec | PPP | NPP | TPV | Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BED versus comparison group Base rate of BED diagnosis = .18 |

|||||||

| Eating much more rapidly than usual | .24 | .52 | .83 | .43 | .88 | .77 | .33 |

| Eating until uncomfortably full | .26 | .63 | .84 | .49 | .90 | .80 | .42 |

| Eating large amounts when not physically hungry | .23 | .66 | .88 | .57 | .91 | .84 | .51 |

| Eating alone because embarrassed | .11 | .40 | .96 | .71 | .87 | .85 | .44 |

| Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty afterward | .32 | .80 | .80 | .49 | .94 | .80 | .48 |

|

BN versus comparison group Base rate of BN diagnosis = .09 |

|||||||

| Eating much more rapidly than usual | .21 | .52 | .83 | .27 | .93 | .79 | .25 |

| Eating until uncomfortably full | .22 | .67 | .84 | .34 | .95 | .82 | .36 |

| Eating large amounts when not physically hungry | .18 | .69 | .88 | .42 | .96 | .86 | .44 |

| Eating alone because embarrassed | .09 | .54 | .96 | .62 | .95 | .91 | .53 |

| Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty afterward | .28 | .93 | .80 | .36 | .99 | .81 | .42 |

|

BED+BN versus comparison group Base rate of combined diagnoses = .27 |

|||||||

| Eating much more rapidly than usual | .27 | .52 | .83 | .53 | .82 | .75 | .35 |

| Eating until uncomfortably full | .29 | .64 | .84 | .59 | .86 | .78 | .47 |

| Eating large amounts when not physically hungry | .27 | .67 | .88 | .67 | .88 | .82 | .55 |

| Eating alone because embarrassed | .15 | .45 | .96 | .80 | .83 | .82 | .48 |

| Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty afterward | .38 | .84 | .80 | .60 | .93 | .81 | .57 |

Note. BN and BED classification was determined by binge eating and/or purging at a frequency of once per week or more for the previous 28 days.

Note. BED = binge eating disorder; BN = bulimia nervosa; sens = sensivity; spec = specificity; PPP = positive predictive power; NPP = negative predictive power; TPV = total predictive value.

All kappa coefficient values are significant at p<.001.

Table 3 shows the base rates and diagnostic efficiency indices for the indicator items separately by gender. The base rates of binge eating in the current sample were very similar among men (.25) and women (.27). The base rates of indicator items were similar for men and women for four of the five indicators. The rate of feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty after binge eating was more common among women (χ2 (1, n=912) = 8.19, p=.004) and was the most frequently reported indicator among women. Among men, the PPP for eating more rapidly than usual was relatively low (≤.5) and suggests that this symptom is not, by itself, an adequate predictor of binge eating. The symptom with the highest NPP for men and women was experiencing disgust, depression, or guilt after binge eating, suggesting that the absence of this feature is associated with the absence of binge eating in both men and women. For men, negative emotions after binge eating had the highest TPV and highest Kappa, whereas for women the feature with the highest TPV and Kappa was eating large amounts when not physically hungry.

Table 3.

Base rates and diagnostic efficiency indices for DSM-IV behavioral criteria for binge eating analyzed separately by gender in BED+BN (N=247).

| BR | Sens | Spec | PPP | NPP | TPV | Kappa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Criterion1 | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F |

| Eating much more rapidly than usual | .32 | .26 | .60 | .51 | .78 | .84 | .49 | .54 | .85 | .82 | .74 | .75 | .35 | .35 |

| Eating until uncomfortably full | .31 | .29 | .63 | .64 | .80 | .84 | .53 | .60 | .86 | .86 | .76 | .79 | .41 | .47 |

| Eating large amounts when not physically hungry | .21 | .27 | .47 | .69 | .87 | .88 | .56 | .68 | .83 | .89 | .77 | .83 | .36 | .57 |

| Eating alone because embarrassed | .15 | .15 | .40 | .46 | .94 | .96 | .71 | .82 | .82 | .83 | .80 | .83 | .40 | .49 |

| Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty afterward | .26 | .39 | .80 | .85 | .93 | .77 | .80 | .58 | .93 | .93 | .90 | .79 | .73 | .54 |

| M | .25 | .27 | .58 | .63 | .86 | .86 | .62 | .64 | .86 | .87 | .79 | .80 | .45 | .48 |

| SD | .07 | .09 | .15 | .15 | .07 | .07 | .13 | .11 | .04 | .05 | .06 | .03 | .16 | .08 |

| F (1, 8) | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.95 | |||||||

| p | .67 | .62 | .90 | .74 | .78 | .90 | .33 | |||||||

Note. BN and BED classification was determined by binge eating and/or purging at a frequency of once per week or more for the previous 28 days.

Note:

Base rate of binge eating (combined binge eating disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (BN)): .25 for men (n=117) and .27 for women (n=796). Sens = sensivity; spec = specificity; PPP = positive predictive power; NPP = negative predictive power; TPV = total predictive value. All kappa coefficient values are significant at p<.001.

Table 4 provides results of ANOVAs testing for group differences on each indicator measured in its original scaling (i.e., 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=always). As a conservative test, we also created study groups defined by the DSM-IV frequency stipulations for binge eating and purging episodes of occurring at least twice weekly. Analyses based on once-weekly and twice-weekly classifications were remarkably similar. For each feature, the BED and BN groups did not differ in frequency ratings, and both groups reported significantly higher levels than the control group.

Table 4.

Mean endorsement of behavioral indicators across BED, BN, and Control groups defined by the once-weekly and twice-weekly frequency threshold.

| BED vs BN vs Controls (1x/week) | BED (n=164) | BN (n=83) | Controls (n=669) | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | η2 | |

| Eating much more rapidly than usual | 3.52 | .93 | 3.49 | .87 | 2.63 | .97 | 2.87 | 1.03 | 77.01 | .14 |

| Eating until uncomfortably full | 3.66 | .76 | 3.70 | .78 | 2.73 | .83 | 2.98 | .92 | 121.59 | .21 |

| Eating large amounts when not physically hungry | 3.74 | .70 | 3.73 | .78 | 2.41 | .94 | 2.77 | 1.06 | 200.70 | .31 |

| Eating alone because embarrassed | 3.14 | 1.22 | 3.36 | 1.28 | 1.67 | .89 | 2.08 | 1.21 | 217.37 | .32 |

| Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty afterward | 4.12 | .86 | 4.44 | .63 | 2.56 | 1.15 | 3.01 | 1.30 | 222.39 | .33 |

| BED vs BN vs Controls (2x/week) | BED (n=81) | BN (n=40) | Neither (n=669) | Total | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | η2 | |

| Eating much more rapidly than usual | 3.54 | 1.00 | 3.90 | .84 | 2.63 | .97 | 2.79 | 1.04 | 60.32 | .13 |

| Eating until uncomfortably full | 3.86 | .75 | 3.90 | .74 | 2.73 | .83 | 2.90 | .92 | 99.87 | .20 |

| Eating large amounts when not physically hungry | 3.90 | .70 | 3.98 | .77 | 2.41 | .94 | 2.65 | 1.06 | 142.62 | .27 |

| Eating alone because embarrassed | 3.45 | 1.15 | 3.63 | 1.26 | 1.67 | .89 | 1.94 | 1.15 | 193.68 | .33 |

| Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty afterward | 4.26 | .85 | 4.45 | .60 | 2.56 | 1.15 | 2.83 | 1.27 | 131.62 | .25 |

Note. Scores reflect Likert scale where 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=always. Post-hoc Scheffe tests found that for all variables, both BED and BN significantly differed from controls at p<.001; BED and BN did not significantly differ on any variable.

Finally, we tabulated the number of individuals within each study group who reported at least three of the five features of binge eating. Chi-square analysis indicated that the study groups differed in the proportion meeting this threshold, χ2 (2, n=916)=365.2, p<.0001, with 7.3% of the control group, 65.2% of the BED group, 72.3% of the BN group reporting three or more of the indicator items for impaired control. The number of features present was strongly correlated with the number of binge episodes (r=.54, p<.001) and purge episodes (r=.29, p<.001) in the overall study group, suggesting that the number of features present is associated with severity of the disorder.

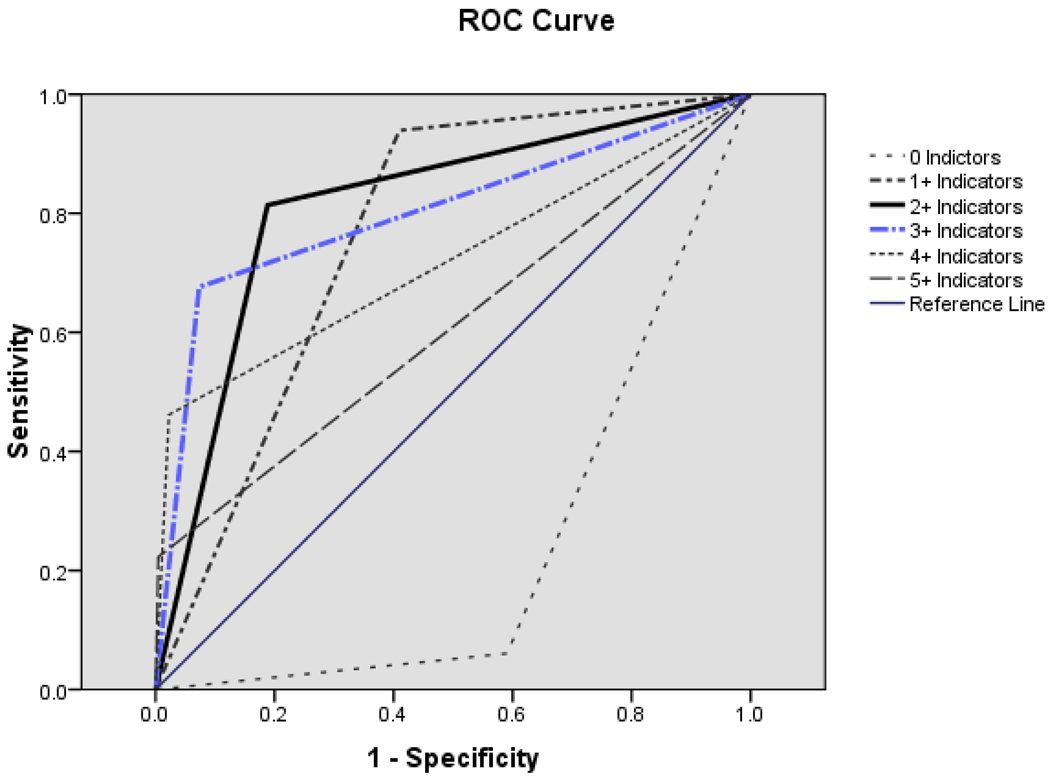

To further examine the clinical utility of the DSM-IV three-or-more indicator threshold, we constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, using the number of indicators endorsed to predict binge eating group membership. ROC curves allow testing the accuracy of the number of indicators endorsed for correctly predicting binge eating status (i.e., inclusion in the BED or BN group). ROC curves for the total number of indicators endorsed are shown in Figure 1. The area under the curve (AUC) for two-or-more indicators yielded the highest absolute value (0.813 (SE=.017), p<.001) for the null hypothesis of true area under the curve = 0.5. An AUC between .70 and .90 is generally viewed to reflect moderate accuracy in prediction (Streiner & Cairney, 2007). Inspection of this ROC analysis revealed that the presence of two-or-more indicators maximized sensitivity (.814) with a 1-specificity of .188. Since a lower false positive rate is desired (Streiner & Cairney, 2007), we also considered the ROC for three-or-more indicators, which yielded a highly significant AUC of .801, p<.001 (95% CI .764–.839), while minimizing the false positive rate (1-specificity value = .073) and maintaining a high sensitivity (.676). Thus, the presence of three-or-more indicators appears to be the best predictor of the presence of binge eating, maximizing sensitivity while protecting against false positives.

Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves predicting BED diagnosis based on number of behavioral indicators for binge eating.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrating the area under the curve (AUC) for the total number of indicators endorsed. A threshold of 3 or more (3+) indicators optimizes the AUC, yielding a high sensitivity (.68) while minimizing the 1-specificity (.07).

Discussion

This study represents, to our knowledge, the first empirical examination of the diagnostic efficiency of the indicators for impaired control to help determine binge eating proposed as part of the research criteria for BED (eating until uncomfortably full, eating large amounts of food when not hungry, eating more rapidly than usual, eating in secret, and feeling disgust, shame, or depression after the episode). Conditional probabilities across the BED, BN, and combined BED+BN groups in comparison to a control group suggest that each indicator has high predictive value with regard to BED and BN diagnoses. PPPs suggest all of the indicators have predictive value, with eating alone because embarrassed (PPP=.80) performing as the best inclusion criterion overall. NPPs were also strong; the highest exclusion criterion was feeling disgust, guilt, or depression after binge eating, indicating that the absence of this criterion was associated with the absence of binge eating. The best overall indicators for correctly identifying binge eating (based on TPV and kappa) were eating large amounts of food when not hungry and eating alone because embarrassed.

We also generated diagnostic efficiency statistics for men and women separately. Among men, the most common feature of binge eating was eating more rapidly than usual, whereas among women the most common feature was feeling disgust, depressed, or guilty afterward. For men, the feature with the greatest TPV was feeling disgust, depressed, or guilty afterward whereas for women the highest TPVs were eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry and eating alone because embarrassed. For both men and women, TPVs and Kappa coefficients were high for all indicators, indicating good diagnostic efficiency for all five of the proposed features for both gender groups.

Finally, we examined the optimal number of indicators to predict diagnoses involving binge eating (BED and BN). Consistent with the DSM and ICD-10 classification schemes for other disorders, a polythetic approach for the binge eating criteria set is used. This approach for binge eating requires that at least three of the five indicators be present. Our analysis of ROC curves found that the three-or-more level yielded the most accurate prediction of binge eating while minimizing the false positive rate.

Some comments regarding the utility of conditional probabilities for clinicians (Grilo et al., 2004) are warranted. Sensitivity and specificity, though valuable in some research applications, have limited use during the process of clinical assessment and diagnosis. Clinicians are more likely to be interested in the likelihood of a disorder given that the patient has a symptom (PPP) than in the likelihood of a symptom given that the patient has a disorder (sensitivity). Similarly, for clinicians, NPP is more useful than specificity. PPP gives us information about the value of a symptom as an inclusion criterion, whereas NPP reflects its value as an exclusion criterion (Faraone et al., 1993; Grilo et al., 2004). In general, PPP is likely to prove to be the more useful of the two, since the DSM approach to diagnosis focuses more on inclusion than exclusion. The advantage of TPV is that it relates to both inclusion and exclusion (Faraone et al., 1993). Coefficient kappa (Cohen, 1960) provides similar information in that it is a derivative of TPV, but controls for chance agreement. Coefficient kappa has an important advantage in that its scale does not tend to inflate the ability of criteria to predict diagnosis: a kappa of zero represents the instance in which agreement is no better than chance, whereas the same case might – depending on the base rates – result in a TPV much greater than zero. Thus, kappa may be the most appropriate index to consider when comparing groups with different base rates. On the other hand, the scale of TPV is more similar to that of PPP and NPP – and it is, therefore, more useful in discussions of diagnostic efficiency that include the consideration of conditional probabilities (Faraone et al., 1993; Grilo et al., 2004).

We briefly note several strengths and limitations of the study to provide context for the findings. Strengths of the study include a large non-treatment-seeking study group assessed anonymously using a validated instrument, the EDE-Q, along with convergent data from a second empirically-supported instrument – the QEWP-R, for determining BED and BN classification. Some research has suggested that the EDE-Q overestimates the frequency of OBEs, which might have led to misclassification of individuals with BED and BN (Crow, Agras, Halmi, Mitchell, & Kraemer, 2002). However, other research has found that the EDE-Q captured fewer OBEs when compared to the EDE interview among BN (Carter, Aime, & Mills, 2001) and BED patients (Wilfley et al., 1997). Therefore, we may have been less likely to include individuals without clinically significant binge eating. In two separate studies with BED, Grilo et al. (Grilo, Masheb et al., 2001a, 2001b) observed a significant correlation between frequencies of OBEs determined using the EDE and EDE-Q and the two methods did not differ significantly in the mean number of OBEs reported. Collectively, these findings support the use of the EDE-Q instrument, augmented by the QEWP-R, to create the criterion diagnostic groups (i.e., BN and BED), especially in light of empirical data showing its performance in detecting purging behaviors (Mond et al., 2007). However, the study groups were formed based on information from the past 28 days, rather than the DSM-IV duration requirements (i.e., three months for BN and six months for BED). Furthermore, we limited the BN group to include only those participants who reported purging behaviors. We did not attempt to create a BN non-purging group since the validity of the EDE-Q for assessing non-purging compensatory activities such as fasting and excessive exercise is uncertain. Future research should utilize interviews.

The current sample of BN participants reported a higher BMI than many epidemiological and clinical samples of BN to date. We speculate that there may be an increasing proportion of overweight individuals with BN as the population rate of overweight has increased (Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Curtin, 2010). Indeed, a recent study reported that increases in the prevalence of comorbid eating disorders and obesity have been greater than increases in either eating disorders or obesity alone (Darby et al., 2009) and research has documented an increased rate of BN in overweight and obese groups (Zachrisson, Vedul-Kjelsas, Gotestam, & Mykletun, 2008). The current sample of BN participants appears older than some clinical and epidemiologic studies of BN. We note, however, that our sample’s age was comparable to that in studies of eating disorders in recent nationally-representative samples in two countries (Darby et al., 2009; Zachrisson et al., 2008) and that our BN sample’s mean age of 33.9 years was slightly higher than the 30.1 mean age for BN reported by the large multisite McKnight Study in the United States (Agras, Crow, Mitchell, Halmi, & Bryson, 2009). Our requirement that participants be at least 18 years of age may have contributed to our observed mean age for BN. Nonetheless, these BMI and age characteristics of the BN group should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings.

A limitation of the current study is that the sample was predominantly female and Caucasian, therefore generalizability to the general population is limited. Future research utilizing larger samples of men and with greater ethnic/racial diversity will be necessary to replicate these findings regarding base rates and diagnostic efficiency indices for the diagnostic indicator items. Another potential limitation is our reliance on a sample of convenience comprising volunteers who self-selected to complete the survey over the internet. Generalizability of our findings to community samples who do not volunteer for research or to clinical samples of patients with BED and BN is uncertain. Future studies of diagnostic efficiency of these and other criteria should ascertain clinical samples which may be characterized by different base rates of the specific eating disorder diagnoses (BED and BN) considered here. This is important because PPP and NPP vary with diagnosis base rates (Faraone et al., 1993; Grilo et al., 1994); PPP tends to increase whereas NPP tends to decrease with increasing diagnosis base rates (Baldessarini et al., 1983; Finn, 1982; Meehl & Rosen, 1955). However, given that the goal was to determine the efficiency of the indicator items for impaired control, the ability to recruit a large control group in the same manner as the diagnostic groups was critical and enhances the validity of the current findings.

To summarize, with these relative methodological strengths and weaknesses as context, this first empirical examination of the diagnostic efficiency of the indicators for impaired control over eating revealed that each indicator has high predictive value with regard to BED and BN diagnoses. Eating alone because embarrassed performed as the best inclusion criterion overall and feeling disgust, guilt, or depression after binge eating performed as the best exclusion criterion (i.e., its absence predicted the absence of BED and BN). The best overall indicators for correctly identifying binge eating as either BED or BN (based on TPV and kappa) were eating large amounts of food when not hungry and eating alone because embarrassed. Additional studies are needed with diverse patient groups characterized by different base rates of diagnoses in order to examine further the efficiency of these indicators for impaired control over eating.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement/Grant support: Dr. White was funded, in part, by NIH K23 DK071646 and Dr. Grilo was supported, in part, by NIH K24 DK070052.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp

The cut-point of often-or-greater was selected based on several reasons. From a clinical and face validity perspective, an endorsement of “sometimes” could correspond with only occasional occurrence. Consideration of a “sometimes” response as indicative of the presence of the feature would yield higher base-rates for the indicators which would, in turn influence some of the conditional probability statistics. Thus, we explored the potential impact of a different cut-point empirically on the diagnostic efficiency indices. Utilizing the cut-point of sometimes (or greater) yielded much higher base rates of the feature (ranging from .33 to .70) and yielded lower TPVs and kappas than did the often-or-greater cut-point. In addition, the specificity values were quite low, indicating a greater risk of false positives. Conversely, the cut-point of always yielded low base-rates of the indicators (≤.05 for 4 indicators), very low sensitivities (<.2 for 4 indicators), very high specificities (all >.9), and ultimately lower TPVs than the often-or-more cut point. Therefore, because the often-or-more cut-point maximized the conditional probabilities and TPVs for each indicator, we chose it as the ideal cut-point to indicate the presence of the indicator items.

References

- Agras WS, Crow S, Mitchell JE, Halmi KA, Bryson S. A 4-year prospective study of eating disorder NOS compared with full eating disorder syndromes. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:565–570. doi: 10.1002/eat.20708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ, Finklestein S, Arana GW. The predictive power of diagnostic tests and the effect of prevalence of illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40(5):569–573. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790050095011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody ML, Walsh BT, Devlin MJ. Binge eating disorder: reliability and validity of a new diagnostic category. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(2):381–386. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Aime AA, Mills JS. Assessment of bulimia nervosa: a comparison of interview and self-report questionnaire methods. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30(2):187–192. doi: 10.1002/eat.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Mitchell J, Walsh BT. A comparison of the binge eating scale, questionnaire for eating and weight patterns-revised, and eating disorder examination questionnaire with instructions with the eating disorder examination in the assessment of binge eating disorder and its symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36(4):434–444. doi: 10.1002/eat.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Agras WS, Halmi K, Mitchell JE, Kraemer HC. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: a multicenter study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;32(3):309–318. doi: 10.1002/eat.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby A, Hay P, Mond J, Quirk F, Buttner P, Kennedy L. The rising prevalence of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviors from 1995 to 2005. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42(2):104–108. doi: 10.1002/eat.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder KA, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Brody ML. Comparison of two self-report instruments for assessing binge eating in bariatric surgery candidates. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:545–560. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination (12th ed.) New York: Guildford Press; 1993. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment; pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Sprich-Buckminster S, Chen W, Tsuang MT. Efficiency of diagnostic criteria for attention deficit disorder: toward an empirical approach to designing and validating diagnostic algorithms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):166–174. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE. Base rates, utilities, and DSM-III: shortcomings of fixed-rule systems of psychodiagnosis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1982;91(4):294–302. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Becker DF, Anez LM, McGlashan TH. Diagnostic efficiency of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: an evaluation in Hispanic men and women with substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(1):126–131. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Hrabosky JI, White MA, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, Masheb RM. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder and overweight controls: refinement of a diagnostic construct. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):414–419. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA. Significance of Overvaluation of Shape/Weight in Binge-eating Disorder: Comparative Study With Overweight and Bulimia Nervosa. Obesity. 2010;18(3):499–504. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001a;69(2):317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obesity Research. 2001b;9(7):418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, et al. Internal consistency, intercriterion overlap and diagnostic efficiency of criteria sets for DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104(4):264–272. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Kisiel CL. Borderline personality disorder: A review of data on DSM-III-R descriptions. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1991;5:340–352. [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE, Rosen A. Antecedent probability and the efficiency of psychometric signs, patterns, or cutting scores. Psychological Bulletin. 1955;52(3):194–216. doi: 10.1037/h0048070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich R, Widiger TA, Landau S. Differential diagnosis of attention deficit and conduct disorders using conditional probabilities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(5):762–767. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.5.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Self-report versus interview assessment of purging in a community sample of women. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15(6):403–409. doi: 10.1002/erv.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(5):551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangle DW, Johnson WG, Carr-Nangle RE, Engler LB. Binge eating disorder and the proposed DSM-IV criteria: psychometric analysis of the Questionnaire of Eating and Weight Patterns. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(2):147–157. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199409)16:2<147::aid-eat2260160206>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner D, Cairney J. What’s under the ROC? An introduction to receiver operating characteristics curves. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52:121–128. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL. Should binge eating disorder be included in the DSM-V? A critical review of the state of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:305–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman ID, Lilienfeld SO. Diagnostic efficiency of symptoms for oppositional defiant disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(5):732–738. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Schwartz MB, Spurrell EB, Fairburn CG. Assessing the specific psychopathology of binge eating disorder patients: interview or self-report? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35(12):1151–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Sysko R. Frequency of binge eating episodes in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: Diagnostic considerations. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42(7):603–610. doi: 10.1002/eat.20726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski S. Binge eating disorder: current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Research. 1993;1:306–324. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachrisson HD, Vedul-Kjelsas E, Gotestam KG, Mykletun A. Time trends in obesity and eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(8):673–680. doi: 10.1002/eat.20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]