Abstract

Gene expression in the mitochondria of the kinetoplastid parasite Trypanosoma brucei is regulated primarily post-transcriptionally at the stages of RNA processing, editing, and turnover. The mitochondrial RNA-binding complex 1 (MRB1) is a recently identified multiprotein complex containing components with distinct functions during different aspects of RNA metabolism, such as guide RNA (gRNA) and mRNA turnover, precursor transcript processing, and RNA editing. In this study we examined the function of the MRB1 protein, Tb927.5.3010, which we term MRB3010. We show that MRB3010 is essential for growth of both procyclic form and bloodstream form life-cycle stages of T. brucei. Down-regulation of MRB3010 by RNAi leads to a dramatic inhibition of RNA editing, yet its depletion does not impact total gRNA levels. Rather, it appears to affect the editing process at an early stage, as indicated by the accumulation of pre-edited and small partially edited RNAs. MRB3010 is present in large (>20S) complexes and exhibits both RNA-dependent and RNA-independent interactions with other MRB1 complex proteins. Comparison of proteins isolated with MRB3010 tagged at its endogenous locus to those reported from other MRB1 complex purifications strongly suggests the presence of an MRB1 “core” complex containing five to six proteins, including MRB3010. Together, these data further our understanding of the function and composition of the imprecisely defined MRB1 complex.

Keywords: RNA editing, trypanosome, MRB1 complex, mitochondria, kinetoplast

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of African sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals, is a member of the clade Kinetoplastida within the phylum Euglenozoa. Members of this order are so named for their kinetoplast (k) DNA, the mitochondrial genome that is a dense catenated network of several dozen DNA maxicircles and thousands of minicircles. The maxicircles encode the traditional mitochondrial genes including ribosomal RNAs and proteins that are components of the respiratory complexes. Twelve of the 18 protein-coding genes present in the kDNA of T. brucei require post-transcriptional editing by uridine insertion and deletion to generate translatable mRNAs. Editing is directed by small (∼60 nt) trans-acting guide RNAs (gRNAs) that are encoded primarily on the minicircles (Blum and Simpson 1990; Sturm and Simpson 1990). The editing reaction is catalyzed by related 20S editosomes or RECCs (RNA editing core complexes), which include the required endonucleolytic, exonucleolytic, nucleoside transferase, and ligase activities (Rusché et al. 1997; Simpson et al. 2004; Lukeš et al. 2005; Stuart et al. 2005; Carnes et al. 2008).

Additional proteins that are not stably associated with the 20S editosomes act as direct or indirect editing accessory factors by affecting the editing process itself, substrate production, and RNA turnover. For example, the heterotetrameric MRP complex (MRP1/2) exhibits RNA annealing activity and is thought to affect editing by facilitating hybridization of some gRNAs to their cognate pre-mRNAs (Aphasizhev et al. 2003; Schumacher et al. 2006). RBP16, another RNA editing accessory factor, has also been shown to facilitate gRNA/pre-mRNA annealing in vitro (Ammerman et al. 2008). Individual knockdown of MRP1/2 and RBP16 demonstrates a role for these proteins in the editing of cytochrome b (CYb) and the stability of certain never-edited transcripts (Pelletier and Read 2003; Vondrušková et al. 2005). Recently, knockdown of MRP1/2 and RBP16 concurrently showed that they contained distinct and overlapping roles in editing and stability that are transcript and life-cycle stage dependent (Fisk et al. 2009a). Another protein, REAP-1, was believed to recruit pre-edited RNAs to the editosome (Madison-Antenucci and Hajduk 2001), but a more recent study of REAP-1 knockout cells suggests a role in RNA stability instead of editing (Hans et al. 2007).

Studies originally performed by Panigrahi et al. (2008) using monoclonal antibodies against mitochondrial proteins, and later confirmed by tandem affinity purification chromatography and mass spectrometry, identified a complex containing numerous proteins with RNA-binding and macromolecular interaction motifs. The complex was named the mitochondrial RNA-binding complex 1 (MRB1). Other groups have also identified this complex (a.k.a. guide RNA-binding complex [GRBC]) (Weng et al. 2008); however, both common and distinct components were reported in the MRB1 complex preparations from different laboratories (Hashimi et al. 2008; Panigrahi et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010). Additionally, some of the MRB1 complex components are also associated with the mitochondrial polyadenylation (kPAP1) complex (Weng et al. 2008). Several proteins associated with MRB1 have been characterized by RNAi-mediated knockdowns and found to impact diverse aspects of mitochondrial RNA metabolism. GAP1 and GAP2 (a.k.a. GRBC2 and GRBC1, or Tb927.2.3800 and Tb927.7.2570, respectively) as well as the REH2 RNP complex (Tb927.4.1500) bind gRNAs and are necessary for the expression and/or stability of the minicircle-encoded gRNAs (Weng et al. 2008; Hashimi et al. 2009; Hernandez et al. 2010). TbRGG2 (a.k.a. TbRGGm and Tb927.10.10830) is a protein with two RNA-binding domains (RRM and RGG), which is required for editing of extensively (pan) edited transcripts (Fisk et al. 2008; Acestor et al. 2009). Moreover, recent evidence suggests that TbRGG2 facilitates editing initiation and 3′–5′ progression of editing by affecting gRNA utilization (Ammerman et al. 2010). The RNA-binding protein, TbRGG1, functions in stabilizing edited RNAs and/or editing efficiency, and has an RNA-dependent interaction with the MRB1 complex (Vanhamme et al. 1998; Hashimi et al. 2008). NUDIX hydrolase (a.k.a. MERS1 or Tb11.01.7290) is required for the stability of edited and potentially pre-edited mRNAs (Weng et al. 2008; Hashimi et al. 2009). Two other MRB1 complex proteins, a C2H2 Zn finger motif containing protein Tb927.6.1680 and Tb11.02.5390 also affect edited mRNA levels (Acestor et al. 2009), but the roles of these proteins and many other MRB1 complex components have yet to be elucidated. Although all of these MRB1 proteins are essential for growth in the insect midgut stage of the parasite (procyclic form; PF) (Fisk et al. 2008; Hashimi et al. 2008, 2009; Weng et al. 2008; Acestor et al. 2009), they appear to have varied affects on mitochondrial RNA metabolism, and may not all be genuine components of all MRB1 complexes. Here, the term MRB1 complex is loosely defined by copurification, and we note that the roles of RNA-dependent interactions, subcomplex associations, and life-cycle stage-dependent interactions in defining this complex have to be addressed.

In all reported MRB1 complex purifications, five proteins are consistently present: GAP1, GAP2, Tb11.02.5390, Tb11.01.8620, and Tb927.5.3010 (Hashimi et al. 2008; Panigrahi et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010). In this study, we utilize RNAi and in vivo tagging and coimmunoprecipitation to examine the function of one of these common MRB1 proteins, Tb927.5.3010, which we term MRB3010. We show here that MRB3010 is essential for growth of both PF and pathogenic bloodstream form (BF) life-cycle stages of T. brucei. Down-regulation of MRB3010 leads to a dramatic inhibition of RNA editing with minimally edited RNAs being somewhat less affected than pan-edited RNAs. MRB3010 depletion does not impact total gRNA levels, but appears to affect editing at early stages of the process. Finally, we identify both RNA-dependent and RNA-independent interactions between MRB3010 and other MRB1 complex proteins. These studies increase our understanding of the function and composition of the imprecisely defined MRB1 complex.

RESULTS

MRB3010 is essential for growth of PF and BF life-cycle stage T. brucei

MRB3010 is a common component of all reported MRB1 complex purifications (Hashimi et al. 2008; Panigrahi et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010). The protein is highly conserved in trypanosomatids with homologs in Trypanosoma cruzi (Tc00.1047053510173.40), Trypanosoma vivax (TvY486_0502380), Trypanosoma congolense (TcIL3000.5.3280), Leishmania braziliensis (LbrM08_V2.0940), Leishmania infantum (LinJ08_V3.1080), and Leishmania major (LmjF08.1170) (Weng et al. 2008). The 57.7-kDa predicted MRB3010 protein exhibits at least 85% amino acid identity to these orthologs over the majority of its primary structure; however, the Trypanosoma proteins are distinguished by a 7-kDa extension at their N-termini, which is absent in Leishmania spp. (Supplemental Fig. 1). MRB3010 contains a ribosomal S2 signature domain, although the significance of this motif is unclear as the protein was not identified in purified mitochondrial ribosomes (Maslov et al. 2006; Zíková et al. 2008).

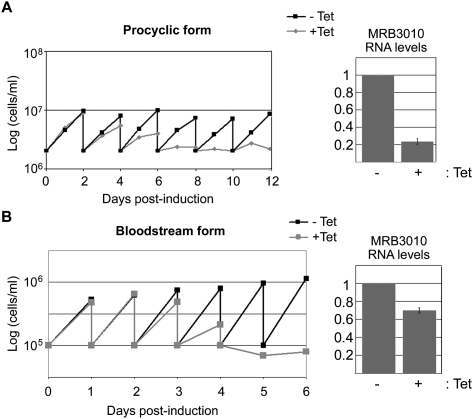

Several components of the MRB1 complex are required for optimal growth of PF (Fisk et al. 2008; Hashimi et al. 2008, 2009; Weng et al. 2008; Acestor et al. 2009) and BF T. brucei (Fisk et al. 2008; Hashimi et al. 2009). To determine whether MRB3010 is similarly important for growth of either life-cycle stage, we generated PF and BF cell lines expressing tetracycline (tet) regulatable RNAi against MRB3010. The online tool, RNAit, was used to determine an MRB3010 gene fragment that is suitable for RNAi and prevents off-target effects (Redmond et al. 2003). MRB3010 RNA levels in PF were reduced to ∼25% of wild-type levels upon tet induction, whereas levels in BF were reduced to ∼70% of those in uninduced cells as measured by qRT–PCR (Fig. 1). Because no antibodies are available for detection of MRB3010, we were unable to directly monitor changes in protein levels. Nevertheless, a dramatic growth defect was observed in both life-cycle stages upon MRB3010 depletion. In both PF and BF, cell growth began to slow between days 3 and 4 post-induction and ceased by days 8 and 5 in PF and BF, respectively. Thus, MRB3010 is essential for growth of both PF and BF T. brucei.

FIGURE 1.

MRB3010 is essential for growth in both PF and BF life-cycle stages. (A) Growth was measured in PF MRB3010 RNAi cells that were uninduced (black) or induced with 1 μg/mL tet (gray). Cell growth, plotted here on a logarithmic scale, was measured every 24 h. Cells were diluted every 2 d to a starting concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL. The bar graph on the right indicates the relative MRB3010 RNA levels in the tet-induced vs. uninduced cells as determined by quantitative RT–PCR. (B) Growth was measured in BF MRB3010 RNAi cells that were uninduced (black) or induced with 1 μg/mL tet (gray). Cell growth was measured every 24 h, followed by dilution of cells to a starting concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL. The bar graph on the right indicates the relative MRB3010 RNA levels in the tet-induced vs. uninduced cells as determined by quantitative RT–PCR.

MRB3010 depletion impacts RNA editing

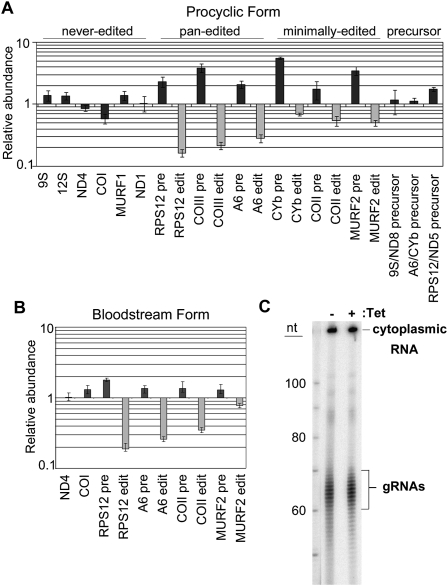

We next asked whether MRB3010 depletion affects the abundance of edited mRNAs, and if so, whether specific classes are altered. RNA from PF and BF cells was isolated after 4 d of tet-induction for use in quantitative PCR. In PF, we measured the levels of three pan-edited and three minimally edited mRNAs (Fig. 2A). Edited versions of pan-edited A6, RPS12, and COIII mRNAs were significantly decreased to levels 15%–35% of those of uninduced cells. The corresponding pre-edited versions were all increased in induced cells. Editing of minimally edited CYb, MURF2, and COII mRNAs was also affected, albeit more modestly, with edited RNA levels in induced cells between 50% and 70% of those in uninduced cells, and the corresponding pre-edited RNAs increased. We also analyzed the abundance of 9S and 12S mitochondrial rRNAs, which do not undergo editing, as well as four never-edited mRNAs. All never-edited RNAs were unchanged upon MRB3010 depletion, with the exception of a small decrease in COI RNA. To ask whether MRB3010 plays a role in precursor RNA processing we measured the levels of three precursors. Levels of 9S/ND8 and A6/CYb precursors were unchanged, while the RPS12/ND5 precursor was increased slightly. qRT–PCR analysis of a smaller panel of RNAs in BF MRB3010 RNAi cells revealed a similar pattern, with all three pan-edited RNAs examined exhibiting a dramatic decrease upon MRB3010 depletion. The edited versions of the minimally edited transcripts COII and MURF2 were also decreased, although to a lesser extent than were the pan-edited RNAs. Never-edited transcripts ND4 and COI were essentially unaffected. To determine whether the inhibition of editing observed upon MRB3010 depletion is a result of destabilization of the total gRNA population, as in knockdowns of the GAP1/2 and REH2 proteins (Weng et al. 2008; Hashimi et al. 2009), we assessed the levels of total gRNAs in PF MRB3010-depleted cells by guanylyltransferase labeling (Fig. 2C). We observed no change in the levels of gRNAs between uninduced and induced cells, demonstrating that MRB3010 has a function distinct from that of GAP1/2 or REH2. Together, these results indicate that MRB3010 plays a role in the RNA editing process. The accumulation of pre-edited mRNAs suggests that this role manifests, at least in part, at the initial stages of the process.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of MRB3010 depletion on the abundance of mitochondrial RNAs. (A) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of mitochondrial maxicircle transcripts from PF MRB3010 RNAi cells 4 d post-induction. Abundance of a given RNA in induced cells relative to that in the uninduced cells is plotted on a log scale. RNA levels were standardized against 18S rRNA, and the numbers represent the mean and standard deviation of at least six determinations. (B) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of mitochondrial maxicircle transcripts from BF MRB3010 RNAi cells 4 d post-induction. RNA levels were standardized against 18S rRNA and numbers represent the mean and standard deviation of at least three determinations. (C) Guanylyl transferase labeling of the total gRNA population from the PF MRB3010 RNAi cells 4 d post-induction. Fifteen micrograms of total RNA were labeled with [α-32P]GTP using guanylyl transferase and resolved on a denaturing gel. RNA input was standardized against the quantity of a labeled cytoplasmic RNA (indicated).

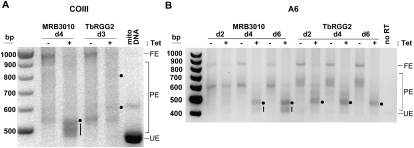

Having shown that MRB3010 depletion affects RNA editing, we wanted to further explore which steps in this process are compromised. To this end, we performed gene-specific RT–PCRs using primers to the constant 5′ and 3′ never-edited regions of pan-edited RNAs, which flank the large edited regions. This approach allows us to visualize the overall 3′–5′ progression of editing within the population of a given mRNA, because increased size of the PCR products correlates with increased U insertion (Schnaufer et al. 2001; Ammerman et al. 2010). We compared the defect in RNA editing in MRB3010-depleted cells with that in cells with ablated TbRGG2, in which both initiation and 3′–5′ progression of editing are compromised (Ammerman et al. 2010). When we analyzed the pan-edited COIII mRNA population by gene-specific RT–PCR, we found that depletion of MRB3010 results in accumulation of both pre-edited and small partially edited RNAs (Fig. 3A). It was striking that many of the partially edited mRNAs accumulating upon MRB3010 depletion cells are smaller than those in TbRGG2-depleted cells. We next analyzed the pan-edited A6 transcript. To confirm that the observed differential effect on editing between the MRB3010 and TbRGG2 RNAi cells is not the result of analysis of RNAs from different post-induction time points, we isolated RNA from MRB3010 and TbRGG2 cells on days 2, 4, and 6 post-induction. Similar to the results we obtained with COIII RNA, we observed accumulation of partially edited A6 mRNAs in MRB3010 depleted cells that are smaller than those seen upon the ablation of TbRGG2, in addition to products of the same size in both cell lines (Fig. 3B). The observation that the editing effect in MRB3010 knockdown cells manifests later than that in TbRGG2 knockdown cells may reflect distinct protein functions or simply different levels of target protein reduction. Together, these data indicate that MRB3010 affects both initiation and progression of RNA editing and that MRB3010 and TbRGG2 impact somewhat different aspects of the editing process.

FIGURE 3.

MRB3010 impacts an early step of the editing process. (A) Gel analysis of COIII RT–PCR reactions using RNAs from MRB3010 and TbRGG2 RNAi cells that were grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of tet for 4 (MRB3010) or 3 (TbRGG2) d. Primers specific to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the COIII gene amplify the entire population of the mRNAs including pre-edited (or unedited) (UE), partially edited (PE), and fully edited (FE) transcripts. Mitochondrial (Mito) DNA was used as a template control for sizing the pre-edited COIII transcript. Dots and dashes represent major editing pause sites in cells depleted for MRB3010 or TbRGG2. (B) Gel analysis of A6 RT–PCR reactions that were performed essentially as described in A, except that primers were specific to the 3′ and 5′ ends of the A6 gene and RNA was collected from MRB3010 and TbRGG2 RNAi cells that were grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of tet for 2, 4, and 6 d.

Association of MRB3010 with MRB1 complex components

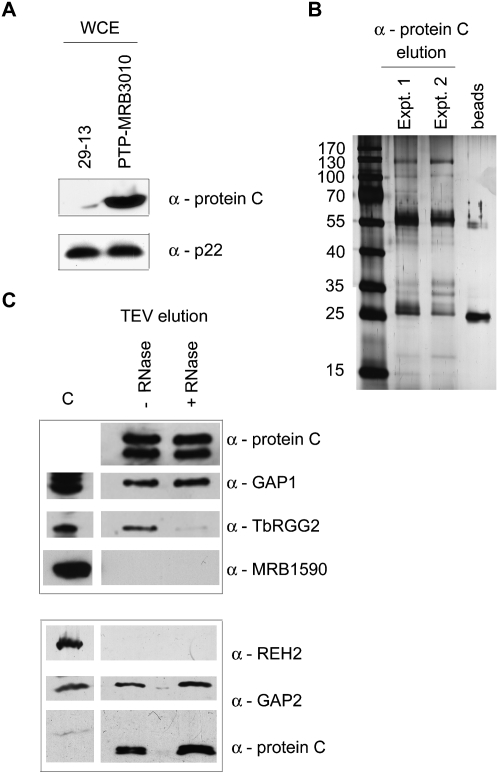

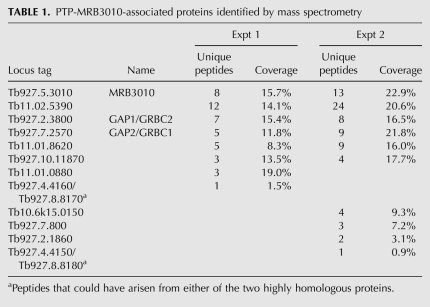

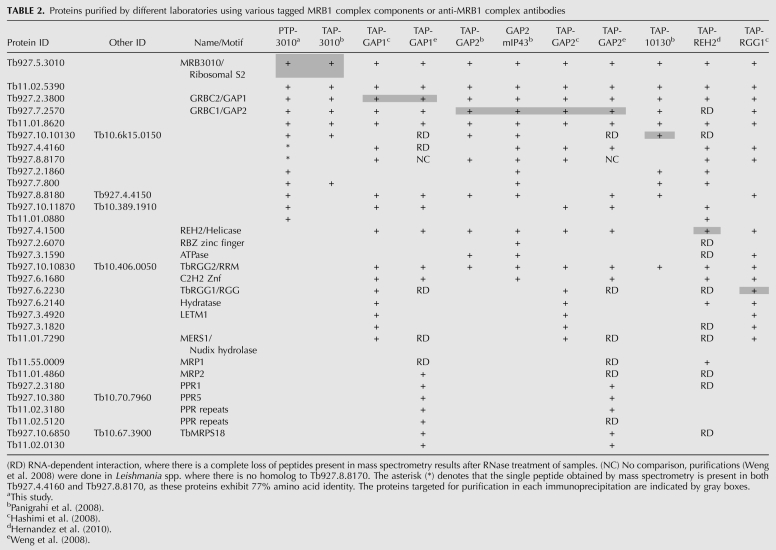

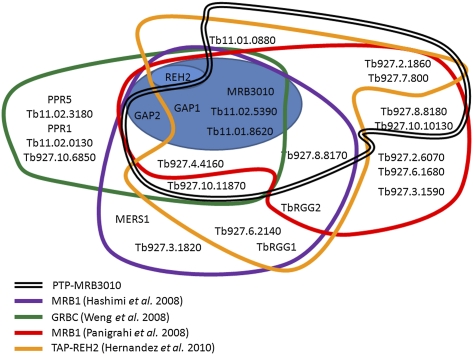

To directly examine the interaction of MRB3010 with MRB1 complex components, we generated a PF cell line expressing C-terminally PTP-tagged MRB3010 from the endogenous locus. The PF PTP-MRB3010 cells exhibited similar growth rates to the parental cells. The PTP tag allows the protein to be detected by anti-Protein C antibody (Fig. 4A) and to be subjected to tandem affinity purification (TAP) via sequential Protein A and Protein C chromatography (Schimanski et al. 2005). All previous MRB1 complex purifications have entailed overexpressed proteins (Hashimi et al. 2008; Panigrahi et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010). Here, expression of tagged MRB3010 from an endogenous locus alleviates any concerns regarding either spurious associations with abundant proteins or lack of association with true partners that are unavailable due to interaction with endogenous protein. We performed two PTP-MRB3010 tandem affinity purifications and examined aliquots of the purified proteins by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4B) and LC-MS/MS (Table 1). In addition to MRB3010, LC-MS/MS identified a total of 11 previously described MRB1 components. Of these 11 proteins, five were found in both experiments. In two cases (Tb927.4.4160/Tb927.8.8170 and Tb927.4.4150/Tb927.8.8180) we were unable to distinguish the origin of a given peptide that could have arisen from either two of two highly homologous proteins. The 11 proteins we identified as copurifying with PTP-MRB3010 have been previously reported in one or more TAP purifications of exogenously expressed MRB1 components, including GAPs, REH2, TbRGG1, MRB10130 (Tb927.10.10130), or MRB3010, and our set of proteins included all seven of the proteins previously purified with MRB3010-TAP (Hashimi et al. 2008; Panigrahi et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010) (Table 2). It was surprising that we failed to identify REH2 in PTP-MRB3010 purifications, because MRB3010 was purified with TAP-tagged REH2 (Hernandez et al. 2010) and REH2 was present in all GAP1/2 purifications (Table 1). However, REH2 was also absent from the MRB3010-TAP purification, which could be the result of the C-terminal tag of PTP-MRB3010 blocking this association, the MRB3010–REH2 interaction being transient, or the interaction being RNA dependent. The remaining proteins identified in tandem affinity purified MRB3010 eluates were presumed contaminants that are commonly observed in TAP purifications and/or have a nonmitochondrial localization (Supplemental Fig. 2). Notably, comparison of the cohorts of proteins identified by different groups with different tagged MRB1 complex components reveals five proteins present in all nine purifications: MRB3010, GAP1, GAP2, Tb11.02.5390, and Tb11.01.8260. These data suggest that the latter five proteins, potentially together with REH2, represent a core MRB1 subcomplex (see Fig. 7, below).

FIGURE 4.

MRB3010 undergoes RNA-dependent and RNA-independent interactions with MRB1 complex components. (A) Western blot analysis of 29-13 or PTP-MRB3010 PF cells with anti-Protein C antibody confirms expression of the tandem affinity tagged MRB3010 protein (top). The p22 protein was used as a loading control (bottom). (B) Ten percent of two PTP-purified MRB3010 samples were separated on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining. Anti-Protein C beads were run as a control for unintended antibody elution. (C) IgG affinity purification of PTP-MRB3010 from cell extracts that were either RNase treated (+ RNase) or left untreated (− RNase). Proteins were eluted from IgG Sepharose 6 Fast Flow columns by TEV protease cleavage and electrophoresed on 10% (top) or 6% (bottom) SDS–polyacrylamide gels, followed by Western blotting with antibodies specific to Protein C (to detect MRB3010-ProtC) and various MRB complex components. (C) Control whole-cell extract, which is from either 29-13 PF cells (top) or PTP-MRB3010 cells (bottom).

TABLE 1.

PTP-MRB3010-associated proteins identified by mass spectrometry

TABLE 2.

Proteins purified by different laboratories using various tagged MRB1 complex components or anti-MRB1 complex antibodies

FIGURE 7.

Overlapping and distinct components of MRB1 complexes isolated by different methods. Gene DB numbers or common names of proteins identified by affinity purification and mass spectrometry from this study and previous studies are outlined in different colors. The blue oval indicates proteins that were identified in the majority of TAP purifications performed with tagged MRB1 components, which may constitute a core subcomplex. GAP2 was identified, but shown to be RNA dependent in the REH2-based purification (Hernandez et al. 2010). REH2 is highlighted because it was not detected with either MRB3010-based purification (Panigrahi et al. 2008; this study); however, the latter may be due to the C-terminal tag, since MRB3010 was detected in the reciprocal REH2-based purification (Hernandez et al. 2010). MRB1 complexes purified by Weng et al. (2008), Hernandez et al. (2010), and in this study were RNase treated, while MRB1 complexes purified by Panigrahi et al. (2008) and Hashimi et al. (2009) were not.

To confirm the LC-MS/MS findings and to determine whether some MRB3010 interactions depend on an RNA bridge, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. To avoid spurious RNase activity that may occur during tandem affinity purification (M Ammerman, unpubl.), we isolated PTP-MRB3010 solely through Protein A Sepharose chromatography, and released bound proteins by TEV protease cleavage. To assess the impact of RNA bridges, we compared samples that were untreated with those that were incubated with an RNase cocktail prior to purification. We then utilized available antibodies to detect proteins associated with MRB3010. Anti-Protein C was used to visualize CBP-MRB3010 and confirm equal recovery and loading. Two bands of CBP-MRB3010 of 55 kDa and 50 kDa were detected (Fig. 4C); the 50-kDa band is likely a breakdown product as it was not present in all preparations and its abundance increased with increasing manipulations of a sample. Immunoblot analysis with antibodies against selected MRB1 components shows that MRB3010 interacts with GAP1, GAP2, and TbRGG2 (Fig. 4C). The interactions with GAP1 and GAP2 appear to involve direct protein–protein contacts, as they are largely refractory to RNase treatment. In contrast, the interaction between MRB3010 and TbRGG2 is primarily RNA mediated and may have been disrupted during the tandem affinity purification used for the LC-MS/MS study. We also confirmed the LC-MS/MS results suggesting that PTP-MRB3010 does not stably interact with REH2 or Tb927.3.1590 (here called MRB1590).

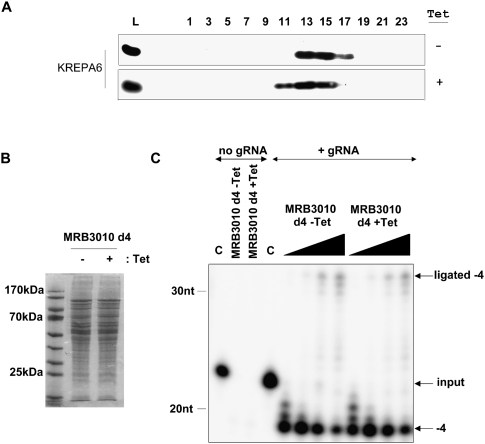

Because MRB3010 is required for efficient RNA editing (Figs. 2, 3), we next asked whether the integrity or activity of the RECC is affected by MRB3010 depletion. Mitochondria isolated from tetracycline-induced and uninduced PF MRB3010 RNAi cells were fractionated on 10%–30% glycerol gradients. The sedimentation pattern of the core RECC component KREPA6 was largely unchanged upon depletion of MRB3010 (Fig. 5A), demonstrating that RECC integrity is unaffected by MRB3010 depletion. To determine whether MRB3010 knockdown affects the activity of the RECC complex, editing assays were carried out on a precleaved deletion substrate using mitochondrial protein extract prepared from uninduced or induced PF MRB3010 RNAi cells. Extracts were analyzed on Coomassie-stained denaturing protein gels to confirm an equal recovery and overall protein profile (Fig. 5B). Precleaved editing assays were performed with the mRNA fragments U5-5″CL and U5-3″CL and gRNA gA6[14]PC-del (Igo et al. 2002). The 5′ and 3′ mRNA fragments are based on the A6 mRNA sequence immediately upstream of and downstream from the first editing site (ES1). The gA6[14]PC-del gRNA is complementary to the U5-5″CL and U5-3″CL fragments and specifies the deletion of four U's. Addition of mitochondrial extract to the RNA substrates resulted in the removal of four U's from the radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment 3′end (shift of the input 5′ mRNA down to −4 in Fig. 5C) and ligation of the 3′ mRNA fragment with the processed 5′ mRNA fragment from which four U's had been removed (shift of the 5′ mRNA up to ligated –4 in Fig. 5C). The assays shown in Figure 5C demonstrate that equal amounts of mitochondrial extracts from MRB3010 RNAi-uninduced or induced cells have equivalent amounts of precleaved editing activity (Fig. 5C). The resistance of RECC activity and integrity to MRB3010 depletion mirrors that seen upon knockdown of GAP1, GAP2, and MERS1 (Weng et al. 2008), and support the idea that the MRB1 complex is physically separate from the RECC, yet has a functional role in editing.

FIGURE 5.

MRB3010 knockdown does not affect RNA editing core complexes. (A) The effect of MRB3010 depletion on the sedimentation of the RNA editing core complex (RECC). Mitochondrial extracts from uninduced (− tet) or tet-induced (+ tet) PF MRB3010 RNAi cells 4 d post-induction were fractionated on 10%–30% glycerol gradients. Alternate gradient fractions were electrophoresed on SDS–polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted with anti-KREPA6 antibody. The mitochondrial extracts loaded on the gradient are shown on the left (abbreviated as L). (B) Equivalent amounts of mitochondrial extract purified from PF MRB3010 cells uninduced (−) or tet induced (+) for 4 d were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie staining. (C) Precleaved deletion editing assays were performed with [Γ -32P]ATP-radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment and 3′ mRNA fragment, but no gRNA (no gRNA); or radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment, 3′ mRNA fragment, and gRNA (+ gRNA). In the no gRNA experiments either a control with no protein (C) or 2.5 μL of the indicated extract was added. Nonspecific ribonucleases in the extracts degraded the radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment when gRNA was not present. In the experiments where gRNA was added either no protein (C) or 1, 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μL of the indicated extracts were added. The migration position of the input radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment is indicated. The −4 nonligated deletion product is labeled −4 and the ligated deletion product is labeled ligated −4.

-32P]ATP-radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment and 3′ mRNA fragment, but no gRNA (no gRNA); or radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment, 3′ mRNA fragment, and gRNA (+ gRNA). In the no gRNA experiments either a control with no protein (C) or 2.5 μL of the indicated extract was added. Nonspecific ribonucleases in the extracts degraded the radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment when gRNA was not present. In the experiments where gRNA was added either no protein (C) or 1, 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μL of the indicated extracts were added. The migration position of the input radiolabeled 5′ mRNA fragment is indicated. The −4 nonligated deletion product is labeled −4 and the ligated deletion product is labeled ligated −4.

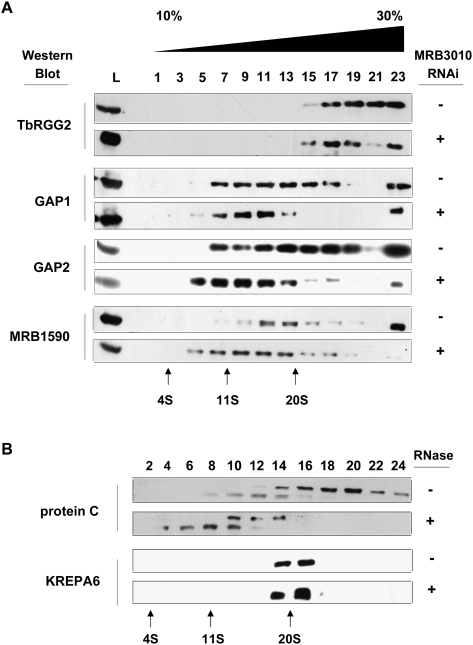

We next investigated the integrity of MRB1 complex(es) upon MRB3010 depletion. Mitochondrial lysates from uninduced and induced MRB3010 RNAi cells were fractionated on 10%–30% glycerol gradients, and the resulting fractions were analyzed by immunoblot for alterations in the sedimentation profiles of MRB1 components (Fig. 6A). TbRGG2 sedimented almost entirely in fractions 15–23, corresponding to particles of >20S, and its sedimentation was unaffected by MRB3010 levels. We note that the sedimentation of TbRGG2 is slightly different from what was previously published (Fisk et al. 2008); this may be the result of different sedimentation conditions or differential disruption of RNA-mediated interactions. In contrast, GAP1 and GAP2 sedimented broadly in fractions 7–17 (∼11S to >20S) of the gradient in uninduced cells, and upon depletion of MRB3010 their sedimentation shifted to fractions 5–13. MRB1590 exhibited a broad distribution (fractions 7–19) whose peak broadened from fractions 11–13 to fractions 7–13 (11S–20S) upon MRB3010 knockdown. Overall, the discernible change in sedimentation of GAP1 and GAP 2-containing complexes upon depletion of MRB3010 demonstrates a requirement for MRB3010 for the integrity of large complexes containing GAP1 and GAP2 proteins. The extension of the sedimentation of MRB1590 to lower fractions upon MRB3010 knockdown may suggest that MRB3010 and MRB1590 are in a common complex, or perhaps knockdown of MRB3010 made available additional proteins or complexes that can interact with MRB1590. Overall, the broad distributions of the different MRB1 complex component proteins on the gradients indicate heterogeneity in MRB1 complexes. MRB3010 appears to be required for stability of some, but not all of the complexes that contain MRB components.

FIGURE 6.

Glycerol gradient sedimentation of MRB complex components. (A) The effect of MRB3010 depletion on the sedimentation of TbRGG2, GAP1, GAP2, and MRB1590-containing complexes. Mitochondrial extracts from uninduced (− tet) or tet-induced (+ tet) PF MRB3010 RNAi cells 4 d post-induction were fractionated on 10%–30% glycerol gradients. Alternate gradient fractions were electrophoresed on SDS–polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. The mitochondrial extracts loaded on the gradient are shown on the left (abbreviated as L). (B) MRB3010 is part of a macromolecular complex that sediments at >20S and has RNA-dependent interactions. Mitochondrial extracts from PF PTP-MRB3010 cells that were either treated with an RNase cocktail (+) or left untreated (–) were fractionated and analyzed as described in A. The position of KREPA6-containing complexes is shown here as a 20S size standard.

With the obvious heterogeneity of MRB1 complexes demonstrated in Figure 6A, it became important to analyze the sedimentation profile of PTP-MRB3010 to determine the size(s) of the complex(es) with which it associates. To this end, mitochondria from PTP-MRB3010 cells were fractionated on 10%–30% glycerol gradients and analyzed by immunoblot, with KREPA6 marking the 20S region of the gradient (Fig. 6B). An anti-Protein C antibody detected the same two bands observed in PTP-MRB3010 pull downs (Fig. 4). The full-length PTP-MRB3010 protein is detected in fractions 14–24, where complexes of 20S or larger sediment. To determine whether MRB3010 association with some or all of these macromolecular complexes is RNA mediated, mitochondrial extracts were treated with a combination of RNases prior to glycerol gradient sedimentation. In Figure 6B, we show that upon RNase treatment, sedimentation of PTP-MRB3010 protein shifts to regions of 20S and lower, consistent with a disruption of PTP-MRB3010-containing complexes via removal of RNA-mediated interactions. This redistribution of MRB3010 demonstrates that the protein exists in complex(es) with RNA-dependent interactions. However, upon RNase treatment we did not observe any PTP-MRB3010 protein shifting to the very top of the gradient, indicating that in addition to engaging in RNA-dependent interactions, MRB3010 also makes RNA-independent contacts with a subset of proteins. Interestingly, comparison of the sedimentation profiles of MRB3010, MRB1590, TbRGG2, GAP1, and GAP2, particularly in uninduced samples (Fig. 6A), reveals substantially different patterns for the five proteins. Collectively, these data are consistent with an MRB1 complex comprising multiple subcomplexes connected by a network of protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions.

DISCUSSION

MRB3010 is a protein common to all MRB1 complex purifications. In this work, we demonstrate that this core MRB1 component is essential for growth and RNA editing in both PF and BF life-cycle stages of T. brucei. Depletion of MRB3010 resulted in a large reduction in the levels of pan-edited mRNAs and a smaller reduction in minimally edited mRNA levels. Total gRNA abundance is unaltered in MRB3010 knockdown cells. Further, MRB3010 depletion similarly affects the editing of COII and MURF2 minimally edited mRNAs, which utilize cis and trans acting gRNAs, respectively. Data indicate that MRB3010 exerts its effect on the editing process indirectly as the integrity and activity of the RECC appear unaltered upon MRB3010 depletion. Nevertheless, MRB3010 functions early in the editing process, as evidenced by the dramatic accumulation of pre-edited and small partially edited mRNAs in MRB3010 knockdown cells. Indeed, this phenotype is reminiscent of that observed upon depletion of several editosome components (Carnes et al. 2005; Salavati et al. 2006; Babbarwal et al. 2007; Tarun et al. 2008; Guo et al. 2010). We also showed that MRB3010 is required for the integrity of some complex(es) that contain MRB1 component proteins, and that it engages in both RNA-independent and RNA-dependent interactions with other MRB1 complex components.

The effect of MRB3010 on RNA editing is distinct from that of other MRB1 components

It is striking that the effects of MRB3010 on RNA editing differ from those of other characterized MRB1 complex components. Even though GAP1 and GAP2 are also common to all MRB1 complex purifications, their apparent function in gRNA stabilization is distinct from the function of MRB3010, which does not impact gRNA stability. The function of MRB3010 also differs from that of TbRGG2, another MRB1 component studied by one of our laboratories (Fisk et al. 2008; Acestor et al. 2009; Ammerman et al. 2010). While depletion of either MRB3010 or TbRGG2 results in a dramatic decrease in the abundance of pan-edited mRNAs, TbRGG2 knockdown does not affect the abundance of minimally edited transcripts whose levels are reduced upon MRB3010 knockdown. Additionally, down-regulation of MRB3010 generally results in greater accumulation of pre-edited mRNAs than does TbRGG2 knockdown as evidenced by qRT–PCR. Gene-specific RT–PCR assays designed to assess the degree of 3′–5′ editing progression also revealed that editing is inhibited at earlier stages in the process in MRB3010-depleted cells than in TbRGG2-depleted cells. Comparisons of the relative levels of various mitochondrial RNAs between MRB3010 RNAi cells and those depleted for other MRB1 complex components, such as TbRGG1, MERS1, Tb927.6.1680, and Tb11.02.5390, also suggest a distinct effect of MRB3010 on mitochondrial RNA metabolism (Hashimi et al. 2008, 2009; Weng et al. 2008; Acestor et al. 2009). How these physically associated proteins impact editing at different stages, and how their effects are coordinated, will be a fascinating subject for future study.

The requirement for MRB3010 in maintaining the stability of complexes containing MRB1 components suggests a structural role for the protein, but we cannot rule out additional functions for MRB3010. An effect on early stages of editing suggests MRB3010 may impact gRNA and/or mRNA utilization, although recombinant MRB3010 does not appear to directly bind gRNAs or mRNAs in vitro using filter-binding assays (M. Ammerman, unpubl.). Moreover, because editing of COII mRNA is affected by MRB3010 knockdown, its effect cannot be restricted to trans-acting gRNAs. One likely possibility is that MRB3010, in the context of a subcomplex containing GAP1/2 proteins that bind gRNAs, is required for proper association of gRNA and/or mRNA with the editosome. In addition, we cannot rule out that the cumulative impact of MRB3010 knockdown on editing may reflect a combination of proteins and processes that have been affected, perhaps resulting from a role for MRB3010 in maintaining the stability of multiple MRB1 subcomplexes.

Macromolecular interactions within the MRB1 complex

Glycerol gradient sedimentation demonstrates that MRB3010 is associated with a large complex, greater than 20S, and that this complex has both RNA-dependent and RNA-independent interactions. Our coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that GAP1 and GAP2 are associated with PTP-MRB3010 following RNase treatment, while the interaction between MRB3010 and TbRGG2 is apparently RNA mediated. LC-MS/MS analysis of proteins purified by tandem affinity purification of endogenously tagged MRB3010 identified all of the proteins found when MRB3010 was overexpressed and purified in addition to six other MRB1 components, one of which was only previously reported to be associated with REH2 (Panigrahi et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010).

Numerous groups have characterized the MRB1 complex with the different purifications containing overlapping and distinct components (Table 2), making the exact composition of the MRB1 complex unclear. Figure 7 summarizes the proteins found in the various MRB1 purifications. Most purifications were done in the absence of RNase treatment; however, in the purifications where −/+ RNase treatment were compared we noted RNA-dependent (RD) protein associations in the cases where there was a complete loss of peptides in LC-MS/MS in RNase-treated samples (Table 2). The results from this study, in combination with those of previous groups, suggest that there is a set of proteins that form a core subcomplex of the MRB1 complex. This core includes GAP1, GAP2, Tb11.02.5390, Tb11.01.8620, Tb927.5.3010, and REH2 (Fig. 7, blue oval). While REH2 was not identified in pulldowns with either endogenously or exogenously tagged MRB3010, purifications of TAP-REH2 did contain MRB3010 (Hernandez et al. 2010). Whether the large C-terminal tag on MRB3010 prevents its normal association with REH2, or whether MRB3010 exists predominantly in a complex without REH2, has to be more closely examined. The consistent copurification of these six proteins suggests that they form a stable particle. However, it is also clear that these proteins do not function exclusively in this context. Copurification of the core subcomplex suggests that the proteins have a common activity when together, but this does not exclude the possibility that these proteins have other activities when they are outside the core subcomplex.

Another set of proteins, including Tb927.4.4160, Tb927.8.8170, and Tb927.10.11870, are present in most, but not all of the MRB1 purifications (Hashimi et al. 2008; Panigrahi et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010). These proteins may associate with the MRB1 core subcomplex individually and/or as components of another subcomplex(es). The observed variation in the composition of the MRB1 complex in preparations purified by tagging of different components likely reflects participation of these proteins in different subcomplexes that can affect more than one step of RNA editing and/or RNA metabolism. In addition, temporal association and disassociation of proteins and subcomplexes is also likely to contribute to the observed heterogeneity in MRB1. Moreover, some of the proteins may not be part of a complex, but may have dynamic and transient interactions with subunits of the complex or RNA. Additional data obtained in this study allow us to refine previous models of the MRB1 complex (Weng et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2010). Further analysis is necessary to define the direct protein–protein interactions and subcomplex compositions and to understand the role of the component proteins in this fascinating complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, RNA interference, and growth curves

The RNAi vector was prepared by amplifying a 506-bp fragment from nucleotides 832 to 1337 of the MRB3010 open reading frame with forward (GGATCCCTAAGCAAGAGGTTCGCCAC) and reverse (CTCGAGGTCTCCCCTGCATCCAGTAA) primers (BamHI and XhoI restriction sites are underlined) and introduced into the BamHI–XhoI restriction sites of p2T7-177. This DNA was transfected into procyclic form (PF) 29-13 and bloodstream form (BF) 427 cells, and transformants were selected with phleomycin. Clonal cell lines were selected by limiting dilution.

For integration of the tandem affinity purification PTP tag into the endogenous MRB3010 locus, primers ApaI 5′ RibS2 (PTP) (5′-CACGGGCCCATGCAAGCACAGAAAGCCG-3′) and NotI 3′ RibS2 (5′-CACGCGGCCGCGCTTGCGGTGTAGACCCACG-3′), encompassing nucleotides 502–1547 of the MRB3010 open reading frame, were used to amplify the 3′-end of MRB3010 and introduce it into the ApaI–NotI restriction sites of pC-PTP PURO (Fisk et al. 2009b). pC-PTP-MRB3010 was then restricted at the unique BpiI site within MRB3010 and transfected into 29-13 PF T. brucei cells. Cells harboring the insert were selected with puromycin and cloned by limiting dilution.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA from uninduced and tet-induced PF and BF MRB3010 RNAi cells was collected at day 4 following induction. Ten micrograms of RNA were treated with a DNA-free DNase kit (Ambion) to remove any residual DNA and reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers and the Taq-Man reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosciences). Twenty-five microliters of real time RT–PCR reactions were then performed with primers specific to pre-edited, edited, and never-edited mitochondrial transcripts as previously described (Carnes et al. 2005; Carnes and Stuart 2007) using a MyiQ real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Primers that flank the junctions of 9S/ND8, A6/CYb, and RPS12/ND5 adjacent genes were previously described (Acestor et al. 2009). Primers RibS2 qPCR Fwd (5′-CCGCTTTTCCTACTGTTGTG-3′) and RibS2 qPCR Rev (5′-ATATTGCGAGCAGAGAGGTG-3′), which amplify nucleotides 68–197 of the MRB3010 open reading frame, were designed to analyze MRB3010 mRNA levels. Results from PF cells were analyzed using iQ5 software (Bio-Rad). Data presented here are normalized using 18S rRNA, although many of the mRNA levels were also confirmed using a β-tubulin standard and found to be comparable to those standardized against 18S rRNA. The level of each RNA is represented as the mean and standard deviation of at least six determinations. Quantitative RT–PCR reactions using BF MRB3010 RNAi cells were performed essentially as described for the PF cells, except reactions were performed using a Rotorgene RG-3000 real time PCR detection system (Corbett Research) with at least three determinations, and data were quantified by the Pfaffl method (Carnes and Stuart 2007).

Guanylyltransferase labeling

Total RNA from the PF MRB3010 RNAi cells uninduced or induced for 4 d with 1μg/mL of tet was purified using Trizol (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Contaminating DNA was removed from the RNA samples using the DNA-free kit (Ambion) following the accompanying protocol. Fifteen micrograms of RNA was labeled with 5 μCi [α-32P]GTP (800 Ci/mmol) in the presence of 1.5 pmol of guanylyltransferase DIR1-545 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 6 mM KCl, 2.5mM DTT, and 20 U of SUPERase-In (Ambion) for 30 min at room temperature (Hayman and Read 1999). Reactions were phenol:chloroform extracted twice, chloroform extracted once, and precipitated in the presence of 2 M ammonium acetate, 20 μg of glycogen, and ethanol. Samples were resuspended in 90% formamide loading buffer and resolved on an 8% acrylamide/7 M urea gel in 1X TBE.

RT–PCR analysis of mitochondrial mRNAs

A total of 30 mL of mid-log trypanosome culture were harvested and resuspended in 1 mL of Trizol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated as per the manufacturer instructions. Contaminating DNA was removed from the RNA using the DNA-free kit (Ambion) and subsequent phenol:chloroform extraction. The following primers that anneal to the never-edited 5′ and 3′ regions of the genes were used for RT–PCR analysis (restriction site underlined):

A6 5′ full NE (5′-AAAAATAAGTATTTTGATATTATTAAAGTAAA-3′),

A6 3′ (5′-ATTAACTTATTTGATCTTATTCTATAACTCC-3′),

COIII 3′ long (5′-AACTTCCTACAAACTACCAATAC-3′) (this primer includes the first two editing sites),

COIII 5′NE (5′-GCGAATTCATTGAGGATTGTTTAAAATTGA-3′).

A total of 50 μL of reverse transcription reactions were performed with 150 pmoles of oligo(dT) primer for COIII and 60 pmoles of A6 3′ primer for A6, and 1 μg of DNase-treated RNA in a 10-μL reaction by incubation at 70°C for 5 min, and slow cooling (30 min) to 20°C. The annealed primer was extended with Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 42°C. PCR reactions were carried out with 3.5 μL of the RT reaction and 20 pmol of gene-specific upstream and downstream primers. PCR was performed using an annealing temperature of 45°C, and products were analyzed on 2.5% agarose gels. Mitochondrial DNA was used as a template control for sizing the pre-edited COIII transcript.

Editing assays

Mitochondrial extracts were prepared by a rapid extract protocol from day 4-uninduced and tet-induced PF MRB3010 RNAi cells as described previously (Rusché et al. 2001; Law et al. 2005). Precleaved deletion assays were performed with the U5-5″CL 5′ mRNA fragment, the U5-3″CLpp 3′ mRNA fragment, and gA6[14]PC-del gRNA (Igo et al. 2002). The U5-5″CL RNA (5″-GGAAAGGGAAAGUUGUGAUUUU-3″) and the U5-3″CLpp RNA (5″-pGCGAGUUAUAGAAUAp-3″) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The gRNA gA6[14]PC-del was prepared by annealing the A6comp1 antisense oligo (GGAAAGGGAAAGTTGTGAGCGAGTTATAGAACCTATAGAACCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAC) to the T7 oligo (GTAATACGACTCACTATA) to act as a template for T7 transcription. The U5-5″CL RNA was labeled with  -32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas). RNAs were purified on 12% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels. Precleaved editing reactions were carried out as previously described (Igo et al. 2002).

-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas). RNAs were purified on 12% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels. Precleaved editing reactions were carried out as previously described (Igo et al. 2002).

Glycerol gradients

Hypotonic purifications of mitochondria from 7.5 × 109-uninduced and tet-induced PF MRB3010 RNAi cells and 5 × 109 PTP-MRB3010 cells were carried out as described previously (Hashimi et al. 2008). The enriched mitochondria were lysed in 1 mL of the lysis buffer (10 mM Tris at pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 μg/mL pepstatin, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM pefabloc) with 1% Triton X-100, for 15 min at 4°C. Lysates were cleared and loaded on 11-mL 10%–30% glycerol gradients and centrifuged at 38,000 rpm in a Beckman SW41 rotor for 12 h at 4°C. Individual 0.5-mL fractions were then collected from the top.

PTP purification and protein analysis

Then, 1.5 × 1010 PTP-MRB3010 PF cells were collected and PTP-MRB3010 was purified by tandem affinity chromatography as described previously (Schimanski et al. 2005; Günzl and Schimanski 2009), except for one minor modification. Prior to binding the IgG Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column, the supernatant was either treated with 40 U of RNaseOUT or with a RNase cocktail containing RNase A (0.1 U/μL), T1 (0.125 U/μL), V1 (0.001/μL), and micrococcal nuclease (0.03 U/μL) for 60 min in ice. TEV elutions from the IgG Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column were analyzed by Western blot. Elutions from the Protein C affinity column were subjected to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; Seattle BioMed). LC-MS/MS was performed using LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The LC system consisted of a fused-silica nanospray needle packed in-house with C18 reverse-phase material. The peptide samples were loaded onto the reversed phase column using a two-mobile-phase solvent system consisting of 0.4% acetic acid in water (A) and 0.4% acetic acid in acetonitrile (B). The mass spectrometer operated in a data-dependent MS/MS mode over the m/z range of from 400 to 2000. For each cycle, the five most abundant ions from each MS scan were selected for MS/MS analysis using 45% normalized collision energy. Dynamic exclusion was used to exclude ions that had been detected twice in a 30-sec window for 3 min. Data analysis involved submitting raw MS/MS data to Bioworks 3.3 (ThermoElectron) and searched using the Sequest algorithm against T. brucei protein database v. 4.0 (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/databases/T.brucei_sequences/T.brucei_genome_v4/), which included additional common contaminants such as human keratin. The Sequest output files were analyzed and validated by PeptideProphet (Keller et al. 2002). Proteins and peptides with a probability score of ≥0.9 were accepted.

Antibodies and Western blots

Fractions from glycerol gradients were electrophoresed on 10% or 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and probed with polyclonal antibodies against GAP1, which was produced against recombinant GAP1 protein (Bethyl Laboratories), GAP2 (Hashimi et al. 2009), TbRGG2 (Fisk et al. 2008), KREPA6 (Tarun et al. 2008) (a generous gift from Ken Stuart, Seattle Biomedical Research Institute), and MRB1590 (antibodies were produced against the peptide [CILPRDAGNSDKPLRD] of Tb927.3.1590 [Bethyl Laboratories]).

Whole-cell lysates from the 29-13 and PTP-MRB3010 cells (equivalent of 1 × 107 cells) were electrophoresed on 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with monoclonal anti-Protein C antibody (Sigma P7058) and polyclonal anti-p22 (Hayman et al. 2001). TEV elutions from tandem affinity purifications of PTP-MRB3010 were run on 6% and 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with anti-MRB1590 (described above), anti-Protein C, anti-GAP1, and anti-GAP2 (Hashimi et al. 2009), anti-TbRGG2 (Fisk et al. 2008), and anti-REH2 antibodies (Hernandez et al. 2010) (a generous gift from Jorge Cruz-Reyes, Texas A&M University).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yuko Ogata for performing the mass spectrometric analysis. We thank Jorge Cruz-Reyes and Ken Stuart for providing antibodies and Sara Zimmer for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant number RO1 AI061580 to L.K.R. and by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic 204/09/1667, the Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic (2B06129, LC07032, and 6007665801), and the Praemium Academiae award to J.L.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2446311.

REFERENCES

- Acestor N, Panigrahi AK, Carnes J, Zíková A, Stuart KD 2009. The MRB1 complex functions in kinetoplastid RNA processing. RNA 15: 277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman ML, Fisk JC, Read LK 2008. gRNA/pre-mRNA annealing and RNA chaperone activities of RBP16. RNA 14: 1069–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman MA, Presnyak V, Fisk JC, Foda BM, Read LK 2010. TbRGG2 facilitates kinetoplastid RNA editing initiation and progression past intrinsic pause sites. RNA 16: 2239–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Nelson RE, Simpson L 2003. A 100-kD complex of two RNA-binding proteins from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae catalyzes RNA annealing and interacts with several RNA editing components. RNA 9: 62–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbarwal VK, Fleck M, Ernst NL, Schnaufer A, Stuart K 2007. An essential role of KREPB4 in RNA editing and structural integrity of the editosome in Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 13: 737–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum B, Simpson L 1990. Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo(U) tail involved in recognition of the preedited region. Cell 62: 391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes J, Stuart KD 2007. Uridine insertion/deletion editing activities. Methods Enzymol 424: 25–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes J, Trotter JR, Ernst NL, Steinberg A, Stuart K 2005. An essential RNase III insertion editing endonuclease in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 16614–16619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes J, Trotter JR, Peltan A, Fleck M, Stuart K 2008. RNA editing in Trypanosoma brucei requires three different editosomes. Mol Cell Biol 28: 122–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk JC, Ammerman ML, Presnyak V, Read LK 2008. TbRGG2, an essential RNA editing accessory factor in two Trypanosoma brucei life cycle stages. J Biol Chem 283: 23016–23025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk JC, Presnyak V, Ammerman ML, Read LK 2009a. Distinct and overlapping functions of MRP1/2 and RBP16 in mitochondrial RNA metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 29: 5214–5225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk JC, Sayegh J, Zurita-Lopez C, Menon S, Presnyak V, Clarke SG, Read LK 2009b. A type III protein arginine methyltransferase from the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem 284: 11590–11600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günzl A, Schimanski B 2009. Tandem affinity purification of proteins. Curr Protoc Protein Sci 55: 19.19.1–19.19.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Ernst NL, Carnes J, Stuart KD 2010. The zinc-fingers of KREPA3 are essential for the complete editing of mitochondrial mRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS ONE 5: e8913 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans J, Hajduk SL, Madison-Antenucci S 2007. RNA-editing-associated protein 1 null mutant reveals link to mitochondrial RNA stability. RNA 13: 881–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimi H, Zíková A, Panigrahi AK, Stuart KD, Lukeš J 2008. TbRGG1, an essential protein involved in kinetoplastid RNA metabolism that is associated with a novel multiprotein complex. RNA 14: 970–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimi H, Čičová Z, Novotná L, Wen YZ, Lukeš J 2009. Kinetoplastid guide RNA biogenesis is dependent on subunits of the mitochondrial RNA binding complex 1 and mitochondrial RNA polymerase. RNA 15: 588–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman ML, Read LK 1999. Trypanosoma brucei RBP16 is a mitochondrial Y-box family protein with guide RNA binding activity. J Biol Chem 274: 12067–12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman ML, Miller MM, Chandler DM, Goulah CC, Read LK 2001. The trypanosome homolog of human p32 interacts with RBP16 and stimulates its gRNA binding activity. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 5216–5225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Madina BR, Ro K, Wohlschlegel JA, Willard B, Kinter MT, Cruz-Reyes J 2010. REH2 RNA helicase in kinetoplastid mitochondria: ribonucleoprotein complexes and essential motifs for unwinding and guide RNA (gRNA) binding. J Biol Chem 285: 1220–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igo RP Jr, Weston DS, Ernst NL, Panigrahi AK, Salavati R, Stuart K 2002. Role of uridylate-specific exoribonuclease activity in Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing. Eukaryot Cell 1: 112–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R 2002. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem 74: 5383–5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law JA, Huang CE, O'Hearn SF, Sollner-Webb B 2005. In Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing, band II enables recognition specifically at each step of the U insertion cycle. Mol Cell Biol 25: 2785–2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukeš J, Hashimi H, Zíková A 2005. Unexplained complexity of the mitochondrial genome and transcriptome in kinetoplastid flagellates. Curr Genet 48: 277–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison-Antenucci S, Hajduk SL 2001. RNA editing-associated protein 1 is an RNA binding protein with specificity for preedited mRNA. Mol Cell 7: 879–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslov DA, Sharma MR, Butler E, Falick AM, Gingery M, Agrawal RK, Spremulli LL, Simpson L 2006. Isolation and characterization of mitochondrial ribosomes and ribosomal subunits from Leishmania tarentolae. Mol Biochem Parasitol 148: 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi AK, Zíková A, Dalley RA, Acestor N, Ogata Y, Anupama A, Myler PJ, Stuart KD 2008. Mitochondrial complexes in Trypanosoma brucei: a novel complex and a unique oxidoreductase complex. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 534–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier M, Read LK 2003. RBP16 is a multifunctional gene regulatory protein involved in editing and stabilization of specific mitochondrial mRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 9: 457–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond S, Vadivelu J, Field MC 2003. RNAit: an automated web-based tool for the selection of RNAi targets in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 128: 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusché LN, Cruz-Reyes J, Piller KJ, Sollner-Webb B 1997. Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J 16: 4069–4081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusché LN, Huang CE, Piller KJ, Hemann M, Wirtz E, Sollner-Webb B 2001. The two RNA ligases of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex: cloning the essential band IV gene and identifying the band V gene. Mol Cell Biol 21: 979–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salavati R, Ernst NL, O'Rear J, Gilliam T, Tarun S Jr, Stuart K 2006. KREPA4, an RNA binding protein essential for editosome integrity and survival of Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 12: 819–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimanski B, Nguyen TN, Günzl A 2005. Highly efficient tandem affinity purification of trypanosome protein complexes based on a novel epitope combination. Eukaryot Cell 4: 1942–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaufer A, Panigrahi AK, Panicucci B, Igo RP Jr, Wirtz E, Salavati R, Stuart K 2001. An RNA ligase essential for RNA editing and survival of the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. Science 291: 2159–2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher MA, Karamooz E, Zíková A, Trantírek L, Lukeš J 2006. Crystal structures of T. brucei MRP1/MRP2 guide-RNA binding complex reveal RNA matchmaking mechanism. Cell 126: 701–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L, Aphasizhev R, Gao G, Kang X 2004. Mitochondrial proteins and complexes in Leishmania and Trypanosoma involved in U-insertion/deletion RNA editing. RNA 10: 159–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart KD, Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Panigrahi AK 2005. Complex management: RNA editing in trypanosomes. Trends Biochem Sci 30: 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm NR, Simpson L 1990. Kinetoplast DNA minicircles encode guide RNAs for editing of cytochrome oxidase subunit III mRNA. Cell 61: 879–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ Jr, Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Proff R, Deng J, Hol W, Stuart K 2008. KREPA6 is an RNA-binding protein essential for editosome integrity and survival of Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 14: 347–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhamme L, Perez-Morga D, Marechal C, Speijer D, Lambert L, Geuskens M, Alexandre S, Ismaili N, Göringer U, Benne R, et al. 1998. Trypanosoma brucei TbRGG1, a mitochondrial oligo(U)-binding protein that co-localizes with an in vitro RNA editing activity. J Biol Chem 273: 21825–21833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vondrušková E, van den Burg J, Zíková A, Ernst NL, Stuart K, Benne R, Lukeš J 2005. RNA interference analyses suggest a transcript-specific regulatory role for mitochondrial RNA-binding proteins MRP1 and MRP2 in RNA editing and other RNA processing in Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem 280: 2429–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng J, Aphasizheva I, Etheridge RD, Huang L, Wang X, Falick AM, Aphasizhev R 2008. Guide RNA-binding complex from mitochondria of trypanosomatids. Mol Cell 32: 198–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zíková A, Panigrahi AK, Dalley RA, Acestor N, Anupama A, Ogata Y, Myler PJ, Stuart K 2008. Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial ribosomes: affinity purification and component identification by mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 1286–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]