Abstract

Autophagy is a lysosome-mediated self-degradation process of eukaryotic cells that, depending on the cellular milieu, can either promote survival or act as an alternative mechanism of programmed cell death (PCD) in terminally differentiated cells. Despite the important developmental and medical implications of autophagy and the main form of PCD, apoptosis, orchestration of their regulation remains poorly understood. Here, we show in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, that various genetic and pharmacological interventions causing embryonic lethality trigger a massive cell death response that has both autophagic and apoptotic features. The two degradation processes are also redundantly required for normal development and viability in this organism. Furthermore, the CES-2-like basic region leucine-zipper (bZip) transcription factor ATF-2, an upstream modulator of the core apoptotic cell death pathway, is able to directly regulate the expression of at least two key autophagy-related genes, bec-1/ATG6 and lgg-1/ATG8. Thus, the two cell death mechanisms share a common method of transcriptional regulation. Together, these results imply that under certain physiological and pathological conditions, autophagy and apoptosis are co-regulated to ensure the proper morphogenesis and survival of the developing organism. The identification of apoptosis and autophagy as compensatory cellular pathways in C. elegans might help us to understand how dysregulated PCD in humans can lead to diverse pathologies, including cancer, neurodegeneration and diabetes.

Key words: Autophagy, Apoptosis, C. elegans, Early development, ATF-2

Introduction

During autophagy (cellular ‘self-eating’), parts of the cytoplasm are delivered into, and degraded within, lysosomes (Mizushima et al., 2008; Levine and Kroemer, 2008). The end products of autophagic degradation can be used to supply the cells with energy under conditions of starvation or provide building blocks for macromolecule synthesis. Autophagy is also required for the effective elimination of damaged, non-functional macromolecules and organelles, which can act as cellular toxins that interfere with cellular functions (Takács-Vellai et al., 2006; Vellai et al., 2009). Thus, autophagy might primarily promote cell survival. Accumulating evidence indicates, however, that autophagy can constitute an alternative mechanism of programmed cell death (PCD) (Maiuri et al., 2007; Kroemer and Levine, 2008), which eliminates superfluous or damaged cells during development or under cellular stress. For example, certain tissues of the Drosophila larva are degraded by a caspase-independent process, which has characteristic autophagic features (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). In mammals, several degenerative pathologies, such as various forms of neuronal demise and muscle atrophy, involve cell death triggered by insufficient or elevated autophagic activity (Levine and Kroemer, 2008). How the regulation of autophagy is linked to that of apoptosis, the main form of PCD, is a fundamental question in biology and has significant medical implications.

The yeast autophagy-related factor Atg6 constitutes a component of a conserved protein complex that is essential for formation of autophagosome membranes during macroautophagy (in this type of autophagy, a subcellular double-membrane-bound structure called the autophagosome is formed to sequester cytoplasmic materials and deliver them into lysosomes or vacuoles) (Klionsky, 2005). Both mammalian and Caenorhabditis elegans orthologs of Atg6 are able to bind the major anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 (B cell lymphoma) and CED-9 (cell death defective), respectively (Liang et al., 1998; Takács-Vellai et al., 2005). Consistently, inactivation of Atg6 orthologs trigger apoptotic cell death in these systems. The tumor suppressor p53 is another regulatory protein that links the apoptotic and autophagic processes; inhibition of the cytoplasmic form of p53 can induce autophagy in mammalian and nematode cells (Tasdemir et al., 2008). Furthermore, insulin and IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor) signaling functions as an upstream modulatory system of both autophagy and apoptosis (Levine and Kroemer, 2008). Hence, the interplay between autophagic and apoptotic processes is now well established. However, the mechanistic basis for how these processes are intertwined in the cellular stress response and during development still remains elusive. Here, we show that these cell death mechanisms share a common method of transcriptional control because expression of key autophagy regulatory genes is regulated by the well-characterized modulator of the core apoptotic cell death pathway, the CES-2-like basic region leucine-zipper (bZip) transcription factor ATF-2.

Results

Various conditions that induce embryonic lethality in C. elegans lead to a massive upregulation of autophagy genes

Initially, we were interested to uncover the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying cell death in response to inactivation of deoxyuridine triphosphate nucleotidohydrolase (dUTPase). This enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of dUTP into dUMP and pyrophosphate, providing the dUMP substrate for de novo dTMP synthesis and preventing uracil incorporation into DNA, which is one of the most common types of endogenously generated DNA damage (Vértessy and Tóth, 2009). In the absence of dUTPase, the cellular dUTP/dTTP ratio is elevated, leading to incorporation of uracil instead of thymine into the newly forming DNA. The DNA base excision repair pathway then removes uracil and restores thymine. When the amount of DNA damage exceeds the repair capacity of the cell, this process eventually leads to the activation of a genotoxic-stress-induced cell death program to eliminate the affected cell. Indeed, in C. elegans, RNA interference (RNAi) of dUTPase leads to embryonic lethality accompanied with activation of apoptosis in a DNA-repair-dependent, but p53-independent, manner (Dengg et al., 2006).

To determine the nature of cellular processes underlying ectopic cell death in dUTPase-deficient nematodes, we performed a morphological analysis of embryos depleted for DUT-1, the nematode dUTPase. In agreement with previous results (Dengg et al., 2006), depletion of DUT-1 caused a fully penetrant embryonic lethality. Several cells of the arrested dut-1(RNAi) embryos displayed characteristic apoptotic features, including highly condensed electron-dense chromatin structures as visualized by electron microscopy (Fig. 1A,B). Furthermore, a nearly twofold increase in the number of apoptotic cell corpses and TUNEL-positive cells was observed in dut-1(RNAi) embryos compared with the wild type (Fig. 1C,D). Apoptosis in these embryos appeared to occur via the canonical cell death pathway because it required the cell-killing proteins CED-4/Apaf1 (Apoptotic protease activating factor) and CED-3/Caspase (Fig. 1C). Because p53 in mammals mediates the cellular response to genotoxic stress, we investigated whether the nematode p53-like protein CEP-1 is involved in cell death triggered by dUTPase deficiency by measuring the relative transcript levels of two CEP-1 target genes, egl-1 and ced-13 (Hofmann et al., 2002; Schumacher et al., 2005). In contrast to control animals, which were treated with ENU (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea), dut-1(RNAi) animals showed no significant transcriptional upregulation (Fig. 1E). These results were evident even in clk-2 and ung-1 mutant backgrounds (Fig. 1E), in which lethality and developmental defects of dut-1(RNAi) animals are known to be rescued (Dengg et al., 2006). Thus, cell death induced by uracil misincorporation into the DNA occurs largely in a CEP-1-independent manner, suggesting the importance of an alternative cell killing machinery in this process.

Fig. 1.

Apoptotic features of embryonic cells depleted of dUTPase. (A) Electron microscopic (EM) image of control cells, which show normal nuclear structure with dispersed and sparse heterochromatic areas. The embryos were fed with bacteria expressing an empty RNAi vector under inducing conditions. (B) The heterochromatic area shows prominent apoptotic morphology (arrows) in two cells of a dut-1(RNAi) (dUTPase deficient) embryo. Scale bars: 1 μm. (C) Depletion of DUT-1 causes an almost twofold increase in the number of apoptotic cell corpses in embryos. This type of cell death occurs in a CED-3- and CED-4-dependent, but LGG-1-independent manner. Red lines indicate the mean number of cell corpses. The lgg-1-deficient mutant strain is actually of lgg-1(tm3489); Ex[LGG-1::GFP] genotype. The translational fusion LGG-1 reporter is able to rescue viability in lgg-1(−) mutant larvae, but as a result of instability of the extrachromosomal array (Ex), the strain behaves as a genetic mosaic. (D) TUNEL staining of wild-type, nuc-1 mutant (positive control) and dut-1(RNAi) embryos. White dots indicate cells with fragmented DNA. The diagram shows the number of TUNEL-positive cells. Bars are mean ± s.e.m. For dut-1(RNAi) embryos, Student's t-test gives P<0.0001 compared with the control. (E) Depletion of DUT-1 is not accompanied with the activation of CEP-1/p53. Quantitative RT-PCR assay showing a weak induction of two CEP-1 targets, egl-1 and ced-13, in wild-type background (grey bars), clk-2(mn159) mutants (black bars) and ung-1(qa7600) mutants (red bars), following treatment with dut-1 RNAi. This contrasts with the strong induction following treatment with ENU (N-Ethyl-N-nitrosourea). clk-2 encodes a telomere-length-regulating protein that is required for the DNA-damage and S-phase-replication checkpoints (Ahmed et al., 2001), ung-1 encodes a uracil DNA glycosylase, which removes misincorporated uracil from the DNA (Dengg et al., 2006).

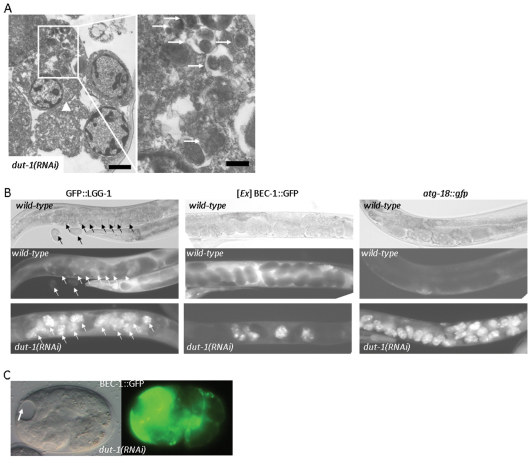

Indeed, we found that several cells in dut-1(RNAi) embryos displayed intense autophagic activity, which was evident from the accumulation of macroautophagic structures representing both autophagosomes and autolysosomes (Fig. 2A) (Meléndez et al., 2003; Sigmond et al., 2008). By contrast, in wild-type embryonic cells, in which autophagy-specific genes were reported to be active (Sigmond et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009), we could hardly detect autophagic structures by electron microscopy (Fig. 1A), suggesting very low levels of autophagic activity at this stage of development. Based upon these findings, we monitored the expression of three GFP (green fluorescent protein)-labeled autophagy-related genes, bec-1/ATG6, lgg-1/ATG8 and atg-18/ATG18, in wild-type versus dut-1(RNAi) embryos (in yeast, Atg8 is a ubiquitin-like protein that is attached to the phosphatidyl-ethanolamine of the growing double isolation membrane; Atg18 binds phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate in the isolation membrane) (Klionsky, 2005; Tóth et al., 2007; Tóth et al., 2008; Sigmond et al., 2008). These autophagy reporters showed a massive expression in embryos produced by hermaphrodites that were treated with dut-1 double-stranded RNA, compared with levels in embryos from animals treated with control RNA (Fig. 2B). Moreover, excessive accumulation of BEC-1 was often associated with obvious tissue atrophy (Fig. 2C). From this, we conclude that autophagy genes become massively upregulated in response to genotoxic stress.

Fig. 2.

Depletion of DUT-1 or dUTPase in C. elegans causes a massive upregulation of autophagy genes. (A) Transmission electron microscopic image showing a cell (arrowhead) with extremely high autophagic activity in a dut-1(RNAi) embryo. The left panel displays an enlargement of the same cell with autophagic elements in various stages of the degradation process (arrows). Note that this cell also shows apoptotic features such as chromatin condensation. Scale bars: 1 μm (left) and 0.25 μm (right). (B) dUTPase deficiency leads to a massive upregulation of three autophagic markers, GFP::LGG-1, BEC-1::GFP and atg-18::gfp (Aladzsity et al., 2007; Sigmond et al., 2008). In wild-type embryos, these GFP-labeled reporters show a faint expression, which manifests as dark balls within the hermaphrodites on the fluorescence pictures (middle panels). The corresponding differential interference contrast (DIC) pictures are in the upper panels. Reporter expression in the dut-1(RNAi) background is shown in the bottom panels: dut-1(RNAi) embryos expressing the reporters are seen as brightly fluorescent balls within the hermaphrodites. Intense expression of BEC-1 is only restricted to several dut-1(RNAi) embryos (white balls), which is due to the mosaicism of the non-integrated BEC-1 reporter. Arrows indicate embryos inside a hermaphrodite transgenic for GFP::LGG-1. (C) Excessive accumulation of a functional BEC-1::GFP reporter in a dut-1(RNAi) embryo is associated with tissue atrophy. The arrow indicates a necrotic area. Left, DIC image; right, the corresponding fluorescent image.

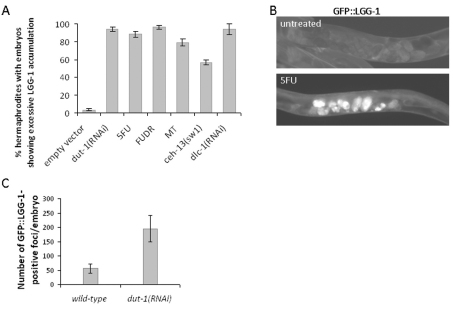

Next, we asked whether this characteristic of autophagy gene activity is specific to dUTPase deficiency or a more general response to diverse cell-death-inducing stimuli. To this end, we treated nematodes with 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate, two inhibitors of de novo dTMP biosynthesis (Longley et al., 2003; Fotoohi and Albertioni, 2008) or applied mutations (e.g. in the Hox gene ceh-13) or gene silencing (e.g. targeting dlc-1, which encodes a dynein light chain-1), which arrest development during embryogenesis (Fig. 3A). These diverse genetic and pharmacological interventions were highly effective in inducing the autophagy reporters used (Fig. 3A,B). Thus, the autophagic and apoptotic machineries appear to be co-induced in response to various stress factors. Hence, autophagy might contribute to the effective elimination of fatally compromised embryonic cells.

Fig. 3.

Various pharmacological and genetic interventions that cause embryonic lethality induce upregulation of autophagy genes. (A) Percentage of hermaphrodites containing embryos with upregulated (excessive) autophagic activity. Control, wild-type animals fed with bacteria containing the empty RNAi vector; dut-1(RNAi), dUTPase deficient animals; 5FU, animals treated with 150 mg/ml 5-fluorouracil.; FUDR, animals treated with 300 mg/ml 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine; MT, animals treated with 300 mg/ml methotexrate; ceh-13(sw1), animals defective for the anterior Hox paralog ceh-13/labial; dlc-1(RNAi), animals defective for dynein light chain. Each of these pharmacological and genetic interventions causes a highly penetrant embryonic lethality (Tihanyi et al., 2010) (for dlc-1, B.H. and T.V., unpublished data). Experiments were performed in triplicate, bars represent s.e.m. P<0.0001 (unpaired t-test). (B) Fluorescent images showing the accumulation of LGG-1 in embryos of wild-type background (top) versus in embryos treated with 5FU (bottom). (C) Depletion of DUT-1/dUTPase enhances autophagic activity in embryos. GFP::LGG-1-positive dots that are thought to correspond to autophagosomal structures were quantified in non-treated (control) and dut-1 RNAi-treated embryos at a single focal plane. Both the number and size of LGG-1-positive dots are higher in dut-1(RNAi) embryos than in control embryos.

We also asked whether autophagy activity – as our electron microscopic (EM) analysis suggested (Fig. 2A) – indeed became elevated in response to depletion of DUT-1. We scored GFP::LGG-1-positive foci specific to autophagosomal structures (note that we integrated the reporter and isogenized the transgenic strain before starting autophagosome quantification) at a given focal plane in control (fed with bacteria carrying the empty vector) and dut-1(RNAi) embryos, and found a significantly higher number of GFP-positive dots in the depleted animals (Fig. 3C). Thus, genotoxic stress triggers autophagic activity in embryos.

The autophagic and apoptotic gene cascades are required redundantly for the viability and development of C. elegans embryos

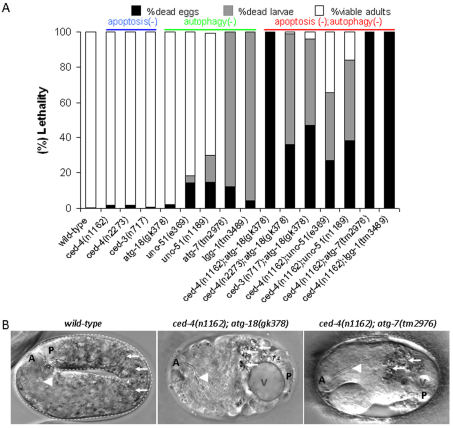

Because autophagy and apoptosis were activated together under various pathological conditions, we hypothesized that the two mechanisms interact in certain physiological processes during development. Unlike in mammals, apoptosis appears to be dispensable for development and viability in C. elegans because apoptosis-deficient single mutant nematodes develop into fertile adults exhibiting a superficially wild-type morphology and behavior (Ellis and Horvitz, 1986; Hengartner et al., 1992; Horvitz, 2003). For example, strong loss-of-function (lf) mutations in ced-4, which encodes an Apaf-1-like protein that is required for both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis, cause no significant change in the gross phenotype under normal growth conditions (Ellis and Horvitz, 1986). Indeed, ced-4(n1162) single mutant hermaphrodites displayed normal morphology and fertility, and they produced viable progeny (Fig. 4A). Similarly, mutant nematodes defective for CED-3 were also viable (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

The apoptotic and autophagic processes are redundantly required for embryonic viability in C. elegans. (A) Viability of mutant animals defective in apoptosis (ced-4 and ced-3 single mutants), autophagy (unc-51, atg-7, atg-18 and lgg-1 single mutants) and both processes (the corresponding double mutant animals). The progeny of ced-4−/−; atg-18−/− double mutants generated by ced-4−/−; atg-18+/− mutant hermaphrodites were scored for the ability to develop into fertile adults. n1162 is a loss-of-function mutation, n2273 is a reduction-of-function (hypomorphic) mutation of ced-4. All of the ced-4(n1162); atg-18(gk378) double mutant animals die as embryos. A portion of ced-4(n2273); atg-18(gk378) and ced-3(n717); atg-18(gk378) double mutant embryos are able to hatch, but these animals arrest development at the early larval stages. Whereas atg-7(tm2976) mutants die as early larvae, all of them die as embryos in ced-4(n1162) mutant background. A similar extent of lethality was observed in lgg-1(tm3489) single mutant vs lgg-1(tm3489); ced-4(n1162) double mutant animals. For each genotype, approximately 300 embryos were assayed. (B) Nematodes defective for both the apoptotic and autophagic processes display severe morphological defects. The left panel shows an elongated, curved wild-type embryo. The middle and right panels show an arrested ced-4(n1162); atg-18(gk378) and ced-4(n1162); atg-7(tm2976) double mutant embryo, respectively. Double mutants exhibit severe body malformations and failure in body elongation. Arrowheads indicate the pharynx, arrows indicate gut fluorescent granules. A, anterior; P, posterior; V, vacuole.

We also examined viability in autophagy-deficient nematodes, and found that mutational inactivation of certain autophagy genes, such as unc-51 (which is similar to the yeast ATG1, which is involved in the initial steps of autophagy induction) (Klionsky, 2005), atg-7 (yeast ATG7 functions in the maturation of autophagic vacuole formation by activating Atg8) (Klionsky, 2005), lgg-1 (which is similar to yeast ATG8) (Meléndez et al., 2003; Aladzsity et al., 2007; Vellai et al., 2008), and atg-18, allow normal embryonic development (Fig. 3A). To explore the combined effect of apoptosis- and autophagy-deficient single mutations on the development of this organism, we generated double mutant nematodes that were defective for both processes. We first assayed survival in ced-4−; atg-18− double mutant animals. Progeny of homozygous ced-4−/−; atg-18−/− double mutants generated by ced-4−/−; atg-18−/+ hermaphrodites died at different stages of embryonic or early larval development, depending on the severity of the ced-4 allele carried (Fig. 4A). For example, ced-4(n1162); atg-18(gk378) double mutants exhibited a fully penetrant (100%) embryonic lethal phenotype (Fig. 4A). The arrested double mutant embryos displayed serious body malformations owing to failure in tissue patterning and body elongation (Fig. 4B). However, the presence of pharyngeal structures and gut autofluorescent granules in these double mutant embryos indicated that the specification of several cell types occurs normally. A similar extent of lethality was also observed in ced-3−/−; atg-18−/− double mutants (Fig. 4A). The viability and fertility of homozygous double mutants produced by ced-4 and ced-3 mutant hermaphrodites heterozygous for the atg-18 mutation can be explained by a maternal effect, which characterizes the inheritance of other autophagy-related genes (Takács-Vellai et al., 2005). To confirm that the developmental arrest phenotype is caused by simultaneous inactivation of apoptosis and autophagy, we also used unc-51, atg-7 and lgg-1 lf mutations to generate double mutants defective for both apoptosis and autophagy. Although the vast majority of atg-7(tm2976) single mutants arrested development at the early larval stages, atg-7(tm2976); ced-4(n1162) double mutants died exclusively as embryos (Fig. 4A). lgg-1(tm3489) mutant nematodes, which themselves developed into early larvae, also showed a highly penetrant embryonic lethality in ced-4 lf mutant genetic background (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, lf mutations in unc-51, which led to viable, fertile, but paralyzed adults, caused a highly penetrant embryonic and larval lethality in the presence of ced-4 lf mutations (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that the autophagic and apoptotic pathways are required redundantly for viability and normal development in C. elegans because single mutants deficient in either of the two processes can complete embryonic development, whereas animals defective for both processes die during embryogenesis.

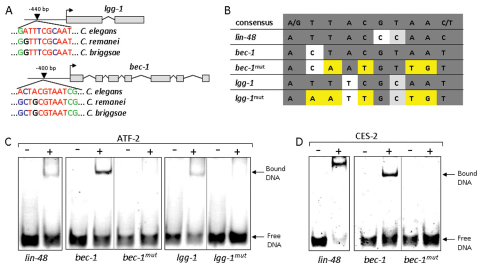

The CES-2-like transcription factor ATF-2 controls the expression of two key autophagy genes, bec-1/ATG6 and lgg-1/ATG8

Because at least three autophagy genes (bec-1, lgg-1 and atg-18) become upregulated during embryogenesis in response to various cell death stimuli (Fig. 2B), we searched for potential apoptosis-related transcription factors with the ability to co-regulate these genes. Strikingly, a CES-2 (cell death specification-2)-specific binding site was found in the upstream regulatory sequences of bec-1 and lgg-1, and these sites were also found to be highly conserved in two other Caenorhabditis species, C. briggsae and C. remanei (Fig. 5A,B). CES-2 is a basic region leucine-zipper (bZip)-like transcription factor that acts as an upstream regulator of the core apoptotic cell death pathway to eliminate the NSM neuronal sister cells (Metzstein et al., 1996). Inactivation of ces-2, however, does not interfere with embryonic viability, and the expression of this gene is restricted to a few cells during embryogenesis (Wang et al., 2006). Therefore, we looked for other CES-2-like transcription factors that have the potential to influence the expression of autophagy genes during early development. One of the closest ces-2 paralogs is atf-2 (cAMP-dependent transcription factor-2), which is broadly expressed in embryos and is required for their viability (Wang et al., 2006). atf-2, together with ces-2, regulates the anatomical and physiological features of the excretory duct cell by modulating expression of lin-48. We assessed whether in vitro translated full-length ATF-2 is able to bind to the potential bZip binding sites found in the bec-1 and lgg-1 regulatory sequences. By performing gel electrophoretic mobility shift assays, we could detect efficient binding of ATF-2 to the elements found in the bec-1 and lgg-1 promoters (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, CES-2 was also able to bind this regulatory region of bec-1 (Fig. 4D). By contrast, ATF-2 and CES-2 failed to bind these sites when the corresponding oligonucleotides were mutated at critical positions. We conclude that ATF-2 binds to the regulatory region of at least two key autophagy genes in vitro.

Fig. 5.

The CES-2-like transcription factor ATF-2 binds to the regulatory region of two key autophagy genes, lgg-1 and bec-1. (A) The regulatory regions of lgg-1 and bec-1 contain putative CES-2-like binding sites, which are conserved in C. briggsae and C. remanei. The numbers indicate the position of the binding sites, relative to the translational initiation sites (arrows). Red color indicates nucleotides that are conserved in the consensus site, non-conserved nucleotides are blue, conserved flanking nucleotides are indicated in green. (B) CES-2-like binding sites within the bec-1 and lgg-1 promoters. Strictly conserved bases are in grey, mutated positions are yellow. (C,D) ATF-2 and CES-2 bind to a conserved binding site in the regulatory region of bec-1 in vitro. ATF-2 is able to bind to a putative binding site of lgg-1 in vitro. ATF-2 at 10 μM (C) or CES-2 at 5 μM (D) were mixed with the corresponding oligonucleotides (at 1 μM) and loaded onto native PAGE. lin-48 oligonucleotide was used as a positive control (Wang et al., 2006).

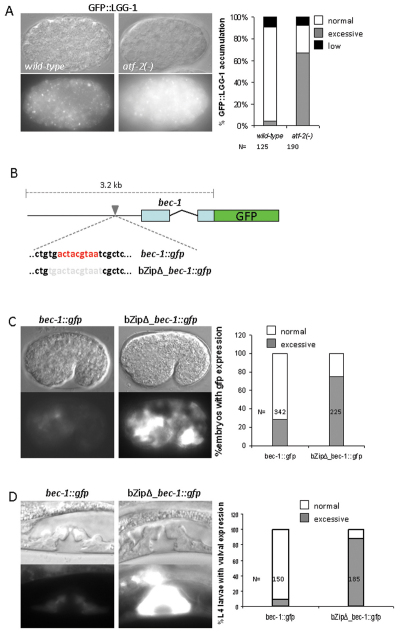

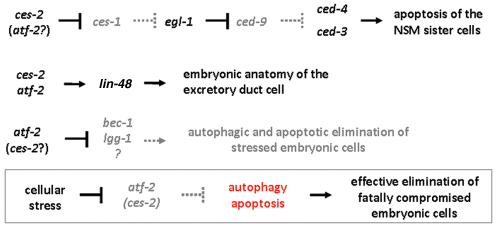

If atf-2 (and possibly also ces-2) mediates or contributes to stress-induced cell death by modulating the activity of certain autophagy genes, we hypothesized that autophagy gene expression should be altered in an ATF-2-deficient background. Indeed, LGG-1 was massively upregulated in atf-2(tm467) mutant embryos, as compared with the wild type (Fig. 6A). We observed a similar extent of BEC-1 upregulation in the atf-2-deficient background (data not shown). Because ATF-2 deficiency causes a highly penetrant embryonic lethality (85%, n=570) (Wang et al., 2006), changes in the expression levels of lgg-1 and bec-1 could, in principle, result from an indirect effect. To exclude this possibility, we generated a transcriptional fusion bec-1::gfp reporter, in which the potential CES-2-like binding site was mutated (Fig. 6B), and examined whether this modification affects bec-1 activity in an otherwise wild-type background. Expression of this bZipΔ_bec-1::gfp reporter was higher in several cells than that of the corresponding wild-type bec-1::gfp reporter (Fig. 6C,D). Upregulation of bec-1 as a result of the absence of the ATF-2 binding site was evident in both embryonic and larval stages. These results suggest that ATF-2 controls the activity of autophagy-related genes in vivo. In conclusion, we demonstrated that a CES-2-like transcription factor might couple the autophagic and apoptotic processes in the control of cell death (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

ATF-2 influences the expression of lgg-1 and bec-1 in vivo. (A) Excessive lgg-1 expression in an atf-2 mutant embryo (right panel) compared with the wild type (left panel). White puncta represent autophagic structures (autophagosomes). The diagram shows the percentage of embryos with excessive accumulation of LGG-1 in wild-type versus atf-2− mutant background. (B) Scheme for two bec-1 transcriptional reporters. In the wild-type sequence (bec-1::gfp), red color indicates the nucleotides of the potential CES-2 binding site. In the mutated construct (bZipΔ_bec-1::gfp), grey color indicates the nucleotides that were removed from the wild-type reporter. (C) In the absence of CES-2 binding site (bZipΔ_bec-1::gfp), bec-1 is upregulated in several cells of a comma stage embryo, compared with the wild-type reporter (bec-1::gfp) at the same developmental stage. The figure shows the percentage of embryos with excessive bec-1 expression. (D) In the absence of the CES-2 binding site, bec-1 is excessively expressed in the vulval tissue at the L4 larval stage. The figure shows the percentage of larvae with excessive bec-1 expression in the vulva. Top panels are Nomarski images; bottom, fluorescent images. The corresponding fluorescent images (wild-type vs mutant backgrounds) were captured with the same exposure times.

Fig. 7.

Model for a shared transcriptional control of autophagy and apoptosis in C. elegans. CES-2 and ATF-2 redundantly activates apoptotic cell death in the sister cells of NSM neurons (top) (Wang et al., 2006). CES-2 and ATF-2 cooperatively promote lin-48 transcription to control the anatomy of the excretory duct cell (middle). ATF-2, and possibly CES-2, inhibits the expression of autophagy genes in embryonic cells (bottom). Cellular stress leads to overactivation of autophagy genes, probably through repressing atf-2 and ces-2, which in turn promotes the death of the affected cell (box). Arrows indicate activation, bars represent inhibitory interactions. EGL-1, BH3-only protein; LIN-48, transcription factor.

Discussion

An understanding of how the autophagic and apoptotic machineries are co-regulated under various physiological and pathological conditions is a fundamental issue in biological research (Kroemer and Levine, 2008; Vellai et al., 2009). In this study, we show that various adverse conditions leading to embryonic lethality upregulate autophagy genes as part of the cell death response (Figs 2 and 3). Thus, autophagy might participate in the effective elimination of fatally compromised cells. This finding supports a dual role for lysosomal degradation in maintaining cellular functions: autophagy primarily promotes cell survival (Mizushima et al., 2008; Levine and Kroemer, 2008), but, depending on the actual cellular milieu, excessive autophagic activity can contribute to, or mediate, cell loss (Maiuri et al., 2007; Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Tóth et al., 2007; Vellai et al., 2007; Kroemer and Levine, 2008).

Autophagy has recently been shown to be required for neuronal development in the mouse embryo and for the specification of somatic and germ cells in C. elegans (Zhang et al., 2009; Fimia et al., 2007). According to our present data, autophagy genes are required redundantly with the core apoptotic cell death pathway for early development and viability in C. elegans (Fig. 4). Although mutant nematodes defective for either of the two processes can survive embryonic development, lf mutations in certain autophagy genes cause severe defects in tissue patterning and body elongation in an apoptosis-deficient background. These results indicate a more general role for autophagy genes in early animal development, and can also explain why apoptosis alone seems to be dispensable for nematode embryogenesis. During embryonic development of C. elegans, the core apoptotic pathway is activated in about 100 cells, whose degrading materials might serve as nutrients for the surviving cells (Angelo and Van Gilst, 2009). In the absence of apoptotis, autophagic activity (cellular self-digestion) might compensate for the absence of this nutrient supply. When both autophagy and apoptosis are compromised, starving embryonic cells might undergo cell death, probably by necrosis, which would eventually arrest development at different stages. Alternatively, proteins that mediate cellular differentiation could be degraded by autophagic and apoptotic processes. The lack of such protein degradation might lead to severe defects in early developmental events.

Human beclin-1 and nematode BEC-1 were previously shown to interact with the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and CED-9, respectively, but found to be dispensable for developmentally regulated apoptosis (Liang et al., 1998; Takács-Vellai et al., 2005). In addition, lf mutations in bec-1 cause embryonic lethality in the absence of maternally deposited BEC-1 (Takács-Vellai et al., 2005). If bec-1 is an essential gene, how do the autophagic and apoptotic processes function redundantly during development? BEC-1 is a multifunctional protein that might not exclusively affect autophagy. Thus, we excluded bec-1 mutant animals from double mutant experiments in this study (Fig. 4).

In support of a direct coupling of these two major death pathways, we identified a bZip-like transcription factor that might co-regulate the autophagic and apoptotic processes under stressful conditions (Figs 5 and 6). The linkage between these two different mechanisms of PCD therefore appears to be more intimate than previously anticipated (Fig. 7). Because the autophagic and apoptotic processes are evolutionarily conserved across divergent animal phyla, similar developmental roles and shared regulatory mechanisms as shown here in nematodes might also operate in higher organisms. This could reflect co-evolution of the two main mechanisms of PCD in Metazoa.

Materials and Methods

Strains and genetics

Wild-type worms were C. elegans var. Bristol (N2). The genotypes of other strains were as follows: ced-4(n1162)III, ced-4(n2273)III, ced-3(n717)IV, atg-18(gk378)V, atg-7(tm2976)IV, unc-51(e369)V, unc-51(n1189)V, lon-1(e185)III, nuc-1(e1392)X, ceh-13(sw1)III, atf-2(tm467)II, buEx070[plgg-1::LGG-1::GFP + rol-6(su1006)], swEx520[pbec-1::BEC-1::GFP + rol-6(su1006)], buEx080[pbZip_bec-1::GFP + rol-6(su1006)], sEx13209[atg-18::GFP], Ex[atf-2::GFP + unc-119(+)]; unc-119(e2498)III; him-5(e1490)V. To generate ced-4; atg-18 double mutant animals, ced-4− single mutant hermaphrodites were mated with heterozygous atg-18(gk378); lon-1(e185) mutant males (lon-1 is closely linked to ced-4). Non-Lon double mutant hermaphrodites that did not segregate Lon progeny were selected, and their progeny were screened for homozygous atg-18 and ced-4 mutations by PCR-based genotyping and subsequent sequencing.

Assaying viability of embryos

5–10 gravid, well-fed hermaphrodites were transferred onto agar plates for 5 hours to lay eggs (around 100 embryos per plate). The number of arrested embryos was determined 2 days later. Each strain was examined in triplicates. The F1 progeny of homozygous double mutants generated by hermaphrodites that are heterozygous for atg-18, unc-51 or atg-7 mutations were scored.

Statistical analysis

The homogeneity of replicates was tested by G statistics. The independence of the separate mutation effects on the survival rates was investigated by testing for the significance of the three-way interaction in the corresponding hierarchical log-linear model.

Electron microscopy

Worms were cut into pieces in a fixative of 3.2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde dissolved in 0.15 M cacodylate buffer. After an overnight aldehyde fixation, samples were washed and embedded in agar. Further processing included postfixation in 0.5% OsO4 and 1% uranyl acetate, dehydration in ascending ethanol series followed by propylene oxide. Samples were embedded by T004 TAAB resin kit with DMP-30. Sections were stained with lead citrate and examined in a JEM100CX II electron microscope.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from 25 worms for each condition and strain analyzed. RNA concentrations were measured and equal amounts reverse transcribed using the Quantitect kit (Qiagen). Between 0.2 and 0.5 μl of the reverse transcription reactions were used for quantitative real-time PCR using the SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma) on an iCycler iQ5 (Bio-Rad). Cycling conditions were: 1× 5 minutes at 5°C and 50 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 20 seconds at 60°C, 40 seconds at 72°C. Fluorescence was measured after each 72°C step. Relative expression levels were determined using the tbg-1 transcript as a standard. Experiments were performed in triplicate. The following reverse and forward primers were used. tbg-1, 5′-AAGATCTATTGTTCTACCAGGC-3′ and 5′-CTTGAACTTCTTGTCCTTGAC-3′; egl-1, 5′-CCTCAACCTCTTCGGATCTT-3′ and 5′-TGCTGATCTCAGAGTCATCAA-3′; ced-13, 5′-GCTCCCTGTTTATCACTTCTC-3′ and 5′-CTGGCATACGTCTTGAATCC-3′. One primer in each pair was designed to bind at the site of an exon-intron boundary to ensure that only cDNA corresponding to processed mRNA was amplified.

Generation of a mutated bec-1::gfp reporter

A genomic fragment containing a bec-1 regulatory region and part of the coding region (covering the first two exons) was amplified with the primers: 5′-CCCAAGCTTGGGAAAAATGCTCTTTATTGGAAAATTG-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCGCGGAGCATCCGAGATGAGCTTC-3′. The resulting fragment was digested with BamHI and HindIII, and cloned into pPD95.75. Transgenic animals were generated and analyzed. Primers used to generate the mutated bZipΔ_bec-1::gfp reporter were: 5′-CGAAGGCACTGAGCGACAGACGGATGGACG-3′ and 5′-CGTCCATCCGTCTGTCGCTCAGTGCCTTCG-3′. A QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) was used to generate the mutated reporter construct.

Gel mobility shift assay

Interaction between His-affinity-purified recombinant full-length ATF-2 and CES-2 proteins and oligonucleotides corresponding to the newly identified potential CES-2-targeted regulatory elements within the promoter regions of lgg-1 and bec-1 was assessed on native TBE-PAGE (8% gels) using ethidium bromide staining. CES-2 was used at 5 μM and ATF-2 at 10 μM final concentration and 1 μM of the oligonucleotides were used in each assay. The protein and oligonucleotide mixtures were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature before loading onto the gel.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Helen M. Chamberlin for the ces-2 and atf-2 cDNA clones, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center funded by the NIH and Shohei Mitani (National Bioresource Project, Japan) for nematode strains. This work was supported by grants from the Hungarian Scientific Research Funds OTKA K68372, K75843 and NK78012 to T.V., OTKA PD75477 to K.T.-V., the National Office for Research and Technology (TECH_08_A1/2-2008-0106) to T.V., and OTKA K68229; CK78646, National Office for Research and Technology JÁP_TSZ_071128_TB_INTER, Hungary; Howard Hughes Medical Institutes #55005628 and #55000342; Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung, Germany; FP6 SPINE2c LSHG-CT-2006-031220 and TEACH-SG LSSG-CT-2007-037198, EU to B.G.V., OTKA-PD 72008 and NIH 1R01TW008130-01 to J.T., and the Research Council of Norway to H.N. and M.D. J.T., T.V. and K.T.-V. are grantees of the János Bolyai scholarship and T.V. and H.N. were members of the COST Action (BM0703) Cancer Control and Genomic Integrity. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

References

- Ahmed S., Alpi A., Hengartner M. O., Gartner A. (2001). C. elegans RAD-5/CLK-2 defines a new DNA damage checkpoint protein. Curr. Biol. 11, 1934-1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aladzsity I., Tóth M. L., Sigmond T., Szabó E., Bicsák B., Barna J., Regos A., Orosz L., Kovács A. L., Vellai T. (2007). Autophagy genes unc-51 and bec-1 are required for normal cell size in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 177, 655-660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo G., Van Gilst M. R. (2009). Starvation protects germline stem cells and extends reproductive longevity in C. elegans. Science 326, 954-958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. L., Baehrecke E. H. (2007). Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell 131, 1137-1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengg M., Garcia-Muse T., Gill S. G., Ashcroft N., Boulton S. J., Nilsen H. (2006). Abrogation of the CLK-2 checkpoint leads to tolerance to base-excision repair intermediates. EMBO Rep. 7, 1046-1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis H. M., Horvitz H. R. (1986). Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell 44, 817-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimia G. M., Stoykova A., Romagnoli A., Giunta L., Di Bartolomeo S., Nardacci R., Corazzari M., Fuoco C., Ucar A., Schwartz P., et al. (2007). Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature 447, 1121-1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotoohi A. K., Albertioni F. (2008). Mechanisms of antifolate resistance and methotrexate efficacy in leukemia cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 49, 410-426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M. O., Ellis R. E., Horvitz H. R. (1992). Caenorhabditis elegans gene ced-9 protects cells from programmed cell death. Nature 356, 494-499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann E. R., Milstein S., Boulton S. J., Ye M., Hofmann J. J., Stergiou L., Gartner A., Vidal M., Hengartner M. O. (2002). Caenorhabditis elegans HUS-1 is a DNA damage checkpoint protein required for genome stability and EGL-1-mediated apoptosis. Curr. Biol. 12, 1908-1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz H. R. (2003). Nobel lecture. Worms, life and death. Biosci. Rep. 23, 239-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D. J. (2005). The molecular machinery of autophagy: unanswered questions. J. Cell Sci. 118, 7-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Levine B. (2008). Autophagic cell death: the story of a misnomer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 1004-1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B., Kroemer G. (2008). Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132, 27-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. H., Kleeman L. K., Jiang H. H., Gordon G., Goldman J. E., Berry G., Herman B., Levine B. (1998). Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J. Virol. 72, 8586-8596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley D. B., Harkin D. P., Johnston P. G. (2003). 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 330-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri M. C., Zalckvar E., Kimchi A., Kroemer G. (2007). Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 741-752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez A., Tallóczy Z., Seaman M., Eskelinen E. L., Hall D. H., Levine B. (2003). Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science 301, 1387-1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzstein M. M., Hengartner M. O., Tsung N., Ellis R. E., Horvitz H. R. (1996). Transcriptional regulator of programmed cell death encoded by Caenorhabditis elegans gene ces-2. Nature 382, 545-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N., Levine B., Cuervo A. M., Klionsky D. J. (2008). Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451, 1069-1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher B., Schertel C., Wittenburg N., Tuck S., Mitani S., Gartner A., Conradt B., Shaham S. (2005). C. elegans ced-13 can promote apoptosis and is induced in response to DNA damage. Cell Death Differ. 12, 153-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmond T., Barna J., Tóth M. L., Takács-Vellai K., Pásti G., Kovács A. L., Vellai T. (2008). Autophagy in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Enzymol. 451, 521-540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takács-Vellai K., Vellai T., Puoti A., Passannante M., Wicky C., Streit A., Kovács A. L., Müller F. (2005). Inactivation of the autophagy gene bec-1 triggers apoptotic cell death in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 15, 1513-1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takács-Vellai K., Bayci A., Vellai T. (2006). Autophagy in neuronal cell loss: a road to death. BioEssays 28, 1126-1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdemir E., Maiuri M. C., Galluzzi L., Vitale I., Djavaheri-Mergny M., D'Amelio M., Criollo A., Morselli E., Zhu C., Harper F., et al. (2008). Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 676-687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tihanyi B., Vellai T., Ari E., Regos Á., Müller F., Takács-Vellai K. (2010). The C. elegans Hox gene ceh-13 regulates cell migration and fusion in a non-colinear way. Implications for the early evolution of Hox clusters. BMC Dev. Biol. 10, 78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth M. L., Simon P., Kovács A. L., Vellai T. (2007). Influence of autophagy genes on ion channel-dependent neuronal degeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1134-1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth M. L., Sigmond T., Borsos É., Barna J., Erdélyi P., Takács-Vellai K., Orosz L., Kovács A. L., Csikós G., Sass M., et al. (2008). Longevity pathways converge on autophagy genes to regulate life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Autophagy 4, 330-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellai T., Tóth M. L., Kovács A. L. (2007). Janus-faced autophagy. A dual role of cellular self-eating in neurodegeneration? Autophagy 3, 461-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellai T., Bicsák B., Tóth M., Takács-Vellai K., Kovács A. L. (2008). Regulation of cell growth by autophagy. Autophagy 4, 507-509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellai T., Takács-Vellai K., Sass M., Klionsky D. J. (2009). The regulation of aging: does autophagy underlie longevity? Trends Cell Biol. 19, 487-497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vértessy B. G., Tóth J. (2009). Keeping uracil out of DNA: physiological role, structure and catalytic mechanism of dUTPases. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 97-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Jia H., Chamberlin H. M. (2006). The bZip proteins CES-2 and ATF-2 alter the timing of transcription for a cell-specific target gene in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 289, 456-465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yan L., Zhou Z., Yang P., Tian E., Zhang K., Zhao Y., Li Z., Song B., Han J., et al. (2009). SEPA-1 mediates the specific recognition and degradation of p granule components by autophagy in C. elegans. Cell 136, 308-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]