Abstract

Adenosine receptor agonists have potent antinociceptive effects in diverse preclinical models of chronic pain. In contrast, the efficacy of adenosine or adenosine receptor agonists at treating pain in humans is unclear. Two ectonucleotidases that generate adenosine in nociceptive neurons were recently identified. When injected spinally, these enzymes have long-lasting adenosine A1 receptor (A1R)-dependent antinociceptive effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models. Furthermore, recent findings indicate that spinal adenosine A2A receptor activation can enduringly inhibit neuropathic pain symptoms. Collectively, these studies suggest the possibility of treating chronic pain in humans by targeting specific adenosine receptor subtypes in anatomically defined regions with agonists or with ectonucleotidases that generate adenosine.

Keywords: adenosine monophosphate, preemptive analgesia, prostatic acid phosphatase, PAP, ecto-5’-nucleotidase, CD73

Adenosine as a therapeutic agent for pain

Adenosine is a purine nucleoside that can signal through four distinct receptors (A1R, A2AR, A2BR and A3R; also known as ADORA1, ADORA2A, ADORA2B and ADORA3). Of these receptors, A1R has received the greatest attention in pain-related studies. A1R is a Gi/o-coupled receptor that is expressed in nociceptive (pain-sensing) neurons, spinal cord neurons and other cells of the body [1–4]. Agonists of this receptor have well-studied antinociceptive (see Glossary) effects in rodents when injected intrathecally, including antihyperalgesic and antiallodynic effects [5]. Furthermore, intrathecal adenosine reduces allodynia and hyperalgesia in patients with chronic pain [6]. In some instances, these pain-relieving effects in humans persist for days to months [7, 8].

Although adenosine has antinociceptive effects in humans [5] and is being studied clinically (Table 1), adenosine and adenosine receptor agonists are not currently used to treat chronic pain in patients. There are several possible reasons for this. For one, there is uncertainty as to whether adenosine or adenosine receptor agonists treat spontaneous pain, a common symptom of chronic pain. In addition, adenosine has limited efficacy in patients (at the doses tested so far) and side effects (transient low back pain, headache) when injected intrathecally as a bolus [9, 10]. These side effects might result from the activation of adenosine A2 receptors—receptors that have pronociceptive (—pain-producing ) and vasodilatory effects when activated peripherally [1, 11]. Adenosine also reduces heart rate when administered intravenously, so there are serious cardiovascular obstacles that must be overcome if adenosine receptor agonists are to be administered systemically (Box 1).

Table 1.

Recent clinical trials that target adenosine receptors associated with chronic pain (clinicaltrials.gov).

| Clinical trial | Sponsor | Route | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clonidine verses adenosine to treat neuropathic pain [NCT00349921] | Wake Forest University (PIs: Eisenach & Rauck) | Intrathecal | Ongoing |

| Dose-response of adenosine for perioperative pain [NCT00298636] | Xsira Pharmaceuticals | Intravenous | Completed - no significant effect [23]. |

| The study of GW493838, an adenosine A1 agonist, in peripheral neuropathic pain [NCT00376454] | GlaxoSmithKline | Not indicated | Completed as of 2006 - results not reported |

| Efficacy and tolerability of novel A2A agonist in treatment of diabetic neuropathic pain (Drug: BVT.115959) [NCT00452777] | Biovitrum | Oral | Completed–was well-tolerated but did not significantly improve pain symptoms (Biovitrum press releasea) |

| Analgesic efficacy and safety study of T-62 in subjects with postherpetic neuralgia (T-62 is an A1R allosteric enhancer [85]) [NCT00809679] | King Pharmaceuticals | Oral | Terminated because some patients experienced transient elevations in liver enzymes |

| Use of AMP to improve tissue delivery of adenosine [NCT00179010] | Vanderbilt University (PI: Biaggioni) | Intrarterial | Suspended, in process of renewing drug application |

Abbreviations: PI, Principal Investigator

Box 1. Cardiovascular side effects of adenosine.

One of the main challenges associated with developing adenosine receptor agonists as analgesics is the need to minimize cardiovascular side effects. A1R is expressed in the atrioventricular and sinoatrial nodes of the heart, and A1R activation in these regions can appreciably slow heart rate. The FDA approved drug Adenocard® (an intravenous formulation of adenosine) exploits this aspect of cardiovascular physiology to treat supraventricular tachycardia—an irregularly fast heartbeat. Based on this physiology, a number of full A1R agonists were developed and tested as antiarrhythmics. Unfortunately, full A1R agonists cause high-grade atrioventricular block and other serious cardiovascular side effects [85]. In turn, these side effects have made it impractical to treat pain with systemic (oral or intravenous) full A1R agonists.

In contrast to full agonists, partial A1R agonists have modest to no effects on cardiovascular function when delivered systemically [85]. Partial agonists activate receptors at submaximal levels and, unlike full agonists, typically do not desensitize receptors. Encouragingly, two partial A1R agonists (CVT-3619-delivered orally; and INO-8875, formerly PJ-875-delivered intraocularly) were well tolerated and had no serious side effects in Phase I clinical trials for indications unrelated to pain. Different partial A1R agonists given systemically had antihyperalgesic effects in a neuropathic pain model with reduced hemodynamic/cardiovascular side effects [86, 87].

These studies collectively suggest that cardiovascular side effects represent a real but surmountable challenge when targeting A1R for analgesic drug development. Further testing of drugs that modulate A1R in preclinical pain models is certainly warranted. Future efforts could include intrathecal injections as well as local peripheral injections of A1R agonists, partial A1R agonists or adenosine-generating ectonucleotidases. While some would argue that the market for intrathecal or local injection therapeutics is small relative to that which can be served with an orally active pill, such injections are more likely to avoid A1R-associated cardiovascular side effects while also engage A1R at spinal or axonal sites. In light of the numerous preclinical studies showing that A1R activation is antinociceptive [5], successful and selective targeting of A1R could serve to benefit the patients who suffer daily from chronic pain.

Recently, several preclinical studies were published that further implicate adenosine receptors as targets for analgesic drug development. This review focuses on mechanistic insights that were gained from these studies and how insights from these studies could be leveraged to more discretely target adenosine receptors for pain control.

Effects on spontaneous pain

A1R activation reduces two common symptoms of chronic pain in humans and rodents, namely mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia [5, 6]. However, the most common and distressing symptom in patients is spontaneous pain [12]. This includes symptoms like burning or stabbing pain. Unlike patients, rodents cannot directly communicate their feelings to human observers, rendering it a challenge to assess how experimental drugs affect spontaneous pain in lab animals.

Recently, King and colleagues developed a conditioned place preference assay to study spontaneous pain-like behaviors in rats [13]. This assay is based on the assumption that relief of spontaneous pain in rodents is rewarding. As such, this assay can only be performed with drugs that are not intrinsically rewarding (thus excluding opioid analgesics which have reward and addiction potential). Using this model, King and colleagues found that clonidine and ω-conotoxin (ziconotide) reduced allodynia and spontaneous pain-like responses following nerve injury. In contrast, intrathecal adenosine reduced allodynia following nerve injury but did not inhibit spontaneous pain-like behaviors. These findings suggest that adenosine engages its targets centrally, because of its effects on allodynia, but does not engage neural pathways responsible for spontaneous pain-like responses. However, given that adenosine and ω-conotoxin act via a similar mechanism (both inhibit N-type calcium channels [14–16]), these contrasting results raise the question–why was ω–conotoxin effective at inhibiting spontaneous pain-like responses while adenosine was not?

In a different study designed to evaluate how drugs affect spontaneous pain-like responses in rodents, Martin and colleagues found that intrathecal clonidine reduced self-administration of the opioid heroin in rats whereas intrathecal adenosine did not [17]. As in the King study, these findings suggest that clonidine but not adenosine can block spontaneous pain following nerve injury (note that this conclusion is based on the assumption that opioids reduce the unpleasant/painful feelings associated with noxious stimuli in rodents). Likewise, in humans with neuropathic pain, intrathecal adenosine had no effect on spontaneous pain but reduced hyperalgesia and allodynia [18], suggesting that adenosine does not inhibit spontaneous neuropathic pain; however, in a surgical pain model, spinal A1R (but not A2AR) activation did inhibit spontaneous (nonevoked) pain [19]. It is thus possible that adenosine inhibits spontaneous pain in some conditions but not others. Such differences are not surprising given that the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying various chronic pain conditions differ [20]. An ongoing clinical trial comparing the analgesic efficacy of clonidine to adenosine may shed additional light on how these drugs affect spontaneous pain in humans (Table 1). Furthermore, new behavioral measures, like the mouse grimace scale [21], could be employed to study how adenosine receptor agonists inhibit additional spontaneous pain-like behaviors.

Preemptive analgesic effects of adenosine

Several groups found that adenosine administered intravenously shortly before and during major surgeries provided long-lasting postoperative pain relief and reduced the need for postoperative opioid analgesics [6, 22], highlighting a preemptive analgesic effect of adenosine. However, in a recent double-blind clinical trial, intravenous adenosine had no preemptive analgesic effects in a similar surgical setting [23]. Why this recent study failed when others succeeded is unclear, but could reflect differences in adenosine doses or differences in the timing of adenosine administration relative to incision.

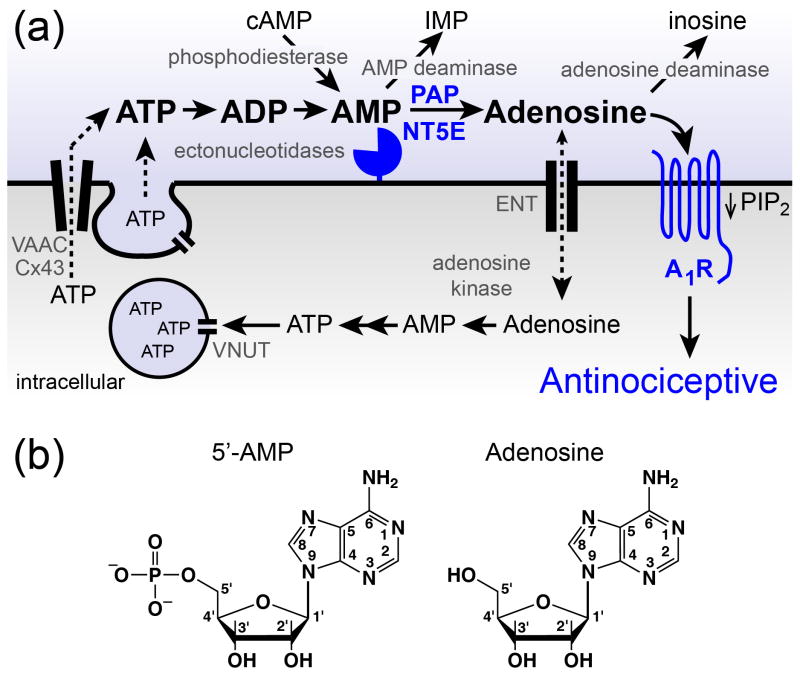

In mice, prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), an ectonucleotidase that generates adenosine over a three day period, provided an enduring (8 day) reduction in nociceptive sensitization if administered intrathecally one day before nerve injury or inflammation [24]. These preemptive antinociceptive effects of PAP were attributed to sustained A1R activation followed by depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), an essential signaling molecule that is required for pronociceptive receptors to sensitize neurons (Figure 1a). These mechanistic findings in rodents indicate that A1R in nociceptive neurons and possibly in spinal neurons must be activated before sensitization is initiated. Extrapolating these animal studies to patients, preemptive analgesia might thus require A1R activation before surgery (tissue damage) and maintained A1R activation during surgery.

Figure 1.

Proteins that regulate extracellular adenosine levels also influence adenosine receptor activation. (a). ATP can be released from neurons and/or glial cells by vesicular and non-vesicular mechanisms. Vesicular nucleotide transporter (VNUT/ SLC17A9), volume activated anion channels (VAAC), Connexin 43 (Cx43). Ectonucleotidases (pacman-like symbol) hydrolyze extracellular nucleotides to adenosine. Adenosine acts on adenosine receptors, including A1R. Sustained A1R activation reduces PIP2 levels and has antinociceptive effects in animals. Adenosine is removed from the extracellular space by metabolic enzymes or by transport into cells via equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs). AMP deaminase metabolizes AMP to inosine monophosphate (IMP). Blue = proteins linked to nociceptive mechanisms by genetic experiments. (b). Structures of 5’-AMP and adenosine.

In the double-blind clinical trial showing no preemptive analgesic effects of intravenous adenosine, adenosine was administered at the time of incision until the end of surgery [23]. Since adenosine infusion began coincident with surgery, PIP2 levels were likely at normal levels when surgery was initiated. As a result, the —inflammatorysoup of chemicals released following tissue damage [20] would be expected to engage PIP2-dependent signaling and transcriptional mechanisms at normal levels [25]. Given that adenosine had preemptive analgesic effects in several clinical trials but not in this trial, additional clinical trials to resolve these differences are warranted. In any new trials, adenosine should be administered well before surgery initiation and one should make sure that adenosine receptors do not desensitize over the course of administration. It may also be worth comparing the preemptive analgesic effects of adenosine with other drugs that activate A1R selectively or for longer durations, such as ectonucleotidases (intrathecally), A1R agonists (provided they don’t cause receptor desensitization), or A1R partial agonists (which do not as readily desensitize receptors). These latter drugs may have more reproducible and larger preemptive analgesic effects when compared to adenosine.

Endogenous generation and metabolism of adenosine

ATP as a source of extracellular adenosine

Many of the studies reviewed here focus on the antinociceptive effects of extracellular adenosine so it is worth reviewing where this nucleoside comes from and how it is metabolized. All cells release ATP at low levels, and release is enhanced upon stimulation, inflammation, pH change, hypoxia, tissue damage or nerve injury [26–32]. Release can occur via vesicular and nonvesicular mechanisms (Figure 1a) that vary in importance depending on cell type [33–36]. For example, a vesicular nucleotide transporter (SLC17A9) pumps ATP into chromaffin granules of PC12 cells, and its knockdown reduced ATP exocytosis from these cells [35]. While SLC17A9 is broadly expressed in tissues such as the spinal cord and neurons of the brain [37], it is not yet known if this transporter pumps ATP into synaptic vesicles, and hence if SLC17A9 contributes to stimulated nucleotide release in sensory neurons or the central nervous system.

It was also recently found that ATP is released from the axons of mouse dorsal root ganglia neurons through a nonvesicular mechanism involving volume-activated anion channels (VAACs; Figure 1a) [36]. VAACs are chloride channels that open in response to cell swelling and membrane stretch and are capable of transporting ATP out of cells [36]. Incidentally, ATP levels are elevated in dorsal root ganglia following nerve injury (which serves as a model of neuropathic pain) [26]. It will be interesting to determine if VAACs and/or SLC17A9 contribute to elevated extracellular nucleotide levels in this and other pathological pain models.

Once released from cells, extracellular ATP is rapidly (<1 s) hydrolyzed to adenosine by a cascade of molecularly distinct ectonucleotidases [38, 39]. Ectonucleotidases have unique substrate specificities; some hydrolyze ATP and ADP to AMP (adenosine 5’-monophosphate; Figure 1b), whereas others hydrolyze AMP to adenosine. Extracellular ATP also signals through P2 purinergic receptors and has pronociceptive effects, including sensitization of nociceptive neurons and activation of spinal microglia, a cell type associated with neuropathic pain [40, 41]. Thus, mechanisms like receptor desensitization and ATP catabolism by ectonucleotidases terminate P2 purinergic receptor signaling.

Other sources of extracellular adenosine

Extracellular adenosine can originate from intracellular pools, where adenosine is passively transported out of cells through equilibrative nucleoside transporters [5] (Figure 1a). Although the process is slow, adenosine can also originate from intracellular or extracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) through the sequential actions of phosphodiesterases and ectonucleotidases [42–44].

Adenosine metabolism

Adenosine is ultimately removed from the extracellular space (Figure 1a) by mechanisms that include: (i) transport into the cell through equilibrative nucleoside transporters (when the extracellular adenosine concentration is higher than the intracellular concentration), (ii) metabolism to inosine by extracellular adenosine deaminase(s), and (iii) phosphorylation to AMP inside cells by adenosine kinase (this reduces the intracellular adenosine concentration, causing an influx of adenosine through equilibrative nucleoside transporters). Indeed, the half-life of extracellular adenosine can be extended by pharmacologically inhibiting these enzymes or transporters [44, 45]. Many of these inhibitors have antinociceptive effects in animal models [5, 46]. However, many of the pharmacological inhibitors used in these studies target multiple enzymes (Box 2). This makes it difficult to determine at a molecular level which enzyme(s) generate adenosine in tissues and hence which should be targeted for analgesic drug development.

Box 2. Inhibitors of adenosine metabolic enzymes target multiple gene products.

The drug 2’-deoxycoformycin (dCF, pentostatin) is commonly used to inhibit adenosine deaminase. While adenosine deaminase is classically treated as if it were one enzyme, there are at least three human genes (Ada, Ada2/Cecr1, Adal) whose products share significant sequence similarity, including within the catalytic domain (Cecr1 is not found in the mouse or rat genome) [88]. ADA and CECR1 both have adenosine deaminase activity and both are inhibited by dCF [88–90]. ADAL has not yet been tested for deaminase activity or sensitivity to dCF. Based on these facts, two to three gene products could contribute to adenosine deaminase activity in any given tissue.

To complicate matters further, dCF and coformycin analogs also inhibit AMP deaminases [91]. Whether dCF inhibits all three molecularly defined AMP deaminases in humans and mice (AMPD1, AMPD2 and AMPD3) is unknown. Adenosine levels increase when adenosine deaminase inhibitors are used [92]. Given the numerous molecular targets for a drug like dCF, elevated adenosine levels could occur through complex mechanisms that include inhibition of adenosine deaminases (ADA, CECR1 and/or ADAL) and/or inhibition of AMPDs—because inhibition of AMPDs elevates AMP, which is subsequently hydrolyzed to adenosine by ectonucleotidases.

The drug 5-iodotubercidin (5-ITU) is commonly used to inhibit adenosine kinase [45]. Underappreciated is the fact that 5-ITU also inhibits equilibrative nucleoside transporters at essentially identical concentrations [93, 94]. Logically then, 5-ITU will primarily elevate extracellular adenosine by inhibiting nucleoside transport. Moreover, intracellular adenosine, which is elevated upon adenosine kinase inhibition, is not likely to exit the cell if transporters are blocked.

Identification of PAP and NT5E—two AMP ectonucleotidases in nociceptive neurons

Using histochemical and molecular approaches, the transmembrane isoform of PAP (also known as ACPP) was recently found to hydrolyze extracellular AMP in nociceptive dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons and in their spinal axon terminals [47, 48]. Since AMP hydrolysis in DRG and spinal cord was reduced but not eliminated in Pap−/− mice, this finding suggested additional ectonucleotidases were present. Indeed, PAP was subsequently found to be coexpressed with ecto-5’-nucleotidase (NT5E; also known as CD73) in nociceptive neurons [49]. NT5E was previously implicated in generating adenosine in nociceptive circuits using pharmacological inhibitors [50–52]. Similar to Pap−/ − mice, AMP hydrolysis in DRG and spinal cord was reduced but not eliminated in Nt5e−/ − knockout mice [53]. Collectively, these experiments provide genetic evidence that nociceptive neurons express at least two distinct enzymes that hydrolyze extracellular AMP: PAP and NT5E (Figure 1a).

Interestingly, nociceptive sensitization was enhanced following nerve injury or inflammation in Pap or Nt5e null mice [47, 49]. A similar behavioral phenotype was observed in A1R−/ − mice [54]. These and other animal model studies suggest that adenosine tonically inhibits nociception [55]. Indeed, adenosine acts through A1R to tonically inhibit excitatory neurotransmission in the dorsal spinal cord where nociceptive neurons terminate [56].

It is currently unknown which enzymes hydrolyze ATP and ADP in nociceptive circuits; however, there are several candidates. Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatases (ENPP1, ENPP2 and ENPP3) hydrolyze ATP directly to AMP whereas four different ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (ENTPD1, ENTPD2, ENTPD3 and ENTPD8) hydrolyze extracellular ATP and ADP to AMP [38]. Several of these ENTPDs are expressed in the spinal cord [57]. Under acidic pH conditions, PAP and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (ACP5) can also hydrolyze ATP and ADP [58, 59]. Also, alkaline phosphatases hydrolyze ATP, ADP and AMP under neutral pH and alkaline conditions [60]. This list of candidate ectonucleotidases likely is an underestimate, because other acid phosphatases have not yet been evaluated for ectonucleotidase activity. Identification of these additional ectonucleotidases will provide molecular insights into the enzymes that metabolize ATP and hence regulate purinergic receptor signaling in nociceptive circuits.

Possible use of recombinant ectonucleotidases to treat chronic pain

Recombinant proteins are used to treat a variety of medical conditions from diabetes to cancer. Recent studies suggest it might be possible to treat chronic pain by taking advantage of the adenosine-generating properties of recombinant ectonucleotidases. In support of this idea, a single intrathecal injection of secretory (nonmembrane bound) versions of PAP or NT5E had long lasting (2–3 day) antinociceptive effects in naïve mice and in mouse models of inflammatory pain and neuropathic pain [47, 53, 58]. In all cases, these antinociceptive effects were dependent on A1R activation, ruling out a role for activation of other adenosine receptor subtypes. PAP has an 11.7 day half-life in blood [61]. This long half-life at body temperature suggests recombinant PAP would be suitable for use in indwelling intrathecal pumps for longer lasting pain control. These pumps are currently used to deliver drugs like opioids and the peptide ω-conotoxin for extended-duration pain control in patients [62].

In light of the side effects and modest efficacy when adenosine is injected intrathecally [9, 10], adenosine-generating ectonucleotidases may have advantages to warrant testing in humans. First, adenosine has a short half-life in the blood (a few seconds) and in spinal cerebrospinal fluid (10–20 minutes) [6], so the limited efficacy of adenosine in humans might reflect rapid metabolism, especially at the sites of action. Often overlooked is the fact that metabolically stable analogs of adenosine (and not adenosine itself) were used in almost all animal studies to demonstrate that A1R activation is antinociceptive [5]. Notably, adenosine does not have antinociceptive effects in naïve rodents whereas stable analogs do [63]. Ectonucleotidases are stable in vivo and have A1R-dependent antinociceptive effects that last for 2–3 days in naïve and nerve injured/inflamed mice. This long duration of action might provide sustained analgesia in patients.

Ectonucleotidases also have an advantage in that they are catalytically restricted, generating adenosine in proportion to substrate (AMP) availability [58]. A bolus injection of an ectonucleotidase would not likely elevate adenosine above a physiologically relevant level, potentially having fewer side effects than bolus adenosine injections. Furthermore, ATP levels increase post nerve injury [26], providing additional substrate for ectonucleotidases to generate adenosine locally. Therefore, ectonucleotidases might generate higher levels of adenosine when animals or patients are in pain [26].

Taken together, ectonucleotidases provide an enzymatic means to generate adenosine locally in the spinal cord and possibly in peripheral tissues. Their antinociceptive effects last for several days, suggesting recombinant versions of these enzymes could be developed for use in patients with chronic pain or to preemptively inhibit pain in surgical settings.

AMP and analogs as possible adenosine receptor prodrugs

When delivered spinally in mice, AMP (combined with 5-ITU to inhibit metabolism of extracellular adenosine) had antinociceptive effects that were partially dependent on Nt5e and fully dependent on A1R activation [49]. AMP also relieved pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia when administered intramuscularly in patients [64]. These observations suggest that AMP or AMP analogs might function as prodrugs—that is, drugs that are inactive until dephosphorylated to adenosine by ectonucleotidases. There is interest in evaluating AMP as an adenosine prodrug in humans (Table 1). Several 2-substituted AMP analogs were recently synthesized that can be hydrolyzed to A2AR agonists by NT5E in vitro [65]. It will be interesting to determine if these prodrugs are dependent on NT5E for activity in animals where multiple AMP hydrolytic enzymes are present. As a potential confound, 2-substituted AMP analogs (but not AMP) are agonists of P2Y receptors [66], a class of P2 purinergic receptors that have pro- and antinociceptive effects when activated [67]. Ultimately, for this prodrug strategy to succeed, AMP or analogs must not activate receptors until they are dephosphorylated by ectonucleotidases. To date, no receptors for AMP have been definitively identified.

Another observation to consider is that AMP can induce a hypometabolic, torpor-like state in mice when administered systemically [68]. Induction of this state by AMP does not require Nt5e [69], although involvement other ectonucleotidases (PAP and alkaline phosphatases) has not been ruled out. There is also controversy as to whether AMP induces a hypometabolic state via adenosine receptor-dependent or independent mechanisms [69, 70].

When taken together, AMP or related analogs could provide a small-molecule approach to target specific ectonucleotidases and adenosine receptors. By developing prodrugs that are dephosphorylated by ectonucleotidases in nociceptive neurons but not in the heart, it might be possible to administer these prodrugs systemically and bypass cardiovascular side effects (Box 1).

Antinociceptive effects of acupuncture require A1R activation

Acupuncture has been used for millennia to treat pain in humans. Perhaps surprisingly, acupuncture can also be performed and has antinociceptive effects in rodents. While there is ongoing debate as to whether the placebo effect contributes to acupuncture pain relief in humans [71, 72], this argument is unlikely to apply to rodents. In mice, acupuncture needle stimulation caused the localized release of nucleotides (ATP, ADP and AMP) as well as adenosine [73]. These antinociceptive effects of acupuncture were entirely dependent on A1R activation, suggesting a link between antinociception and extracellular adenosine. Although not directly tested, this suggests that ectonucleotidases convert nucleotides to adenosine in skeletal muscle. In addition, local injection of an A1R agonist into an acupuncture point had antinociceptive effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models, consistent with studies showing that peripheral A1R activation is antinociceptive [4, 74]. Therefore, it might be possible to treat pain in patients by locally injecting adenosine or A1R agonists. Local injections are unlikely to have cardiovascular side effects, which are associated with systemic A1R activation (Box 1) [1].

Acupuncture and adenosine receptor agonists have a relatively short duration of action (<4 hr) in chronic pain models when compared to ectonucleotidases (2–3 days) [47, 58, 73] . It will thus be interesting to determine if injection of recombinant ectonucleotidases like PAP into acupuncture points has longer lasting A1R-dependent antinociceptive effects (—Papupuncture ) than acupuncture or agonist injections. The basal concentration of AMP is greater than ATP, ADP or adenosine near acupuncture points [73], so there is ample substrate for PAP to hydrolyze. The link between A1R and acupuncture is also intriguing because it could explain why acupuncture isn’t always effective in humans. Caffeine is the most widely consumed psychoactive compound in the world and blocks A1R and A2AR. Interestingly, caffeine also blocks the antinociceptive effects of acupuncture in rats at doses that are comparable to what humans consume in a single cup [75, 76]. Whether or not caffeine affects acupuncture effectiveness in humans is unknown but clearly is important to study.

Recent developments in A1R and A2AR pharmacology

A1R activation inhibits nociceptive sensitization by depleting PIP2

Recently, it was found that sustained A1R activation by PAP leads to phospholipase C-mediated depletion of PIP2 in cultured cells and in mouse DRG [24]. Depletion of this essential phosphoinositide reduced noxious thermosensation, in part through inhibition of transient receptor potential cation channel V1 (TRPV1), a thermosensory channel that requires PIP2 for activity [77]. Depletion of PIP2 also enduringly reduced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia caused by inflammation, nerve injury and pronociceptive receptor activation.

Conversely, PIP2 levels were significantly elevated in DRG from Pap−/ − mice, which correlated with an enduring enhancement of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia [24, 47]. Sensitization was also enhanced when sensitizing stimuli were paired with direct intrathecal injection of PIP2 [24]. Importantly, nociceptive sensitization was only reduced or enhanced if PIP2 levels were reduced or elevated before the animals were inflamed, nerve injured or stimulated with pronociceptive ligands. These findings collectively suggest that A1R activation regulates an underlying —phosphoinositide tone that in turn influences noxious thermosensation and nociceptive sensitization.

A2AR agonists enduringly inhibit neuropathic pain symptoms

Recently, two different A2AR agonists (ATL313 and CGS21680) were found to enduringly reverse allodynia and hyperalgesia caused by nerve injury in rats (for up to four weeks after a single intrathecal injection) [78]. This represents a very long lasting antinociceptive effect and runs counter to previous studies showing that A2A/BR activation, at least when activated peripherally, has pronociceptive and vasodilatory effects [1, 11]. The doses of CGS21680 Loram and colleagues used to achieve these enduring effects were extraordinarily low—1 μM in 1 μL, which represents 1 pmol of drug. This is 15,000 times lower than the 15 nmol Effective Dose-50 calculated by Lee and Yaksh for CGS21680 when administered intrathecally in a neuropathic pain model [79]. Likewise, others found that 10 nmol CGS21680 injected intrathecally had no or short-lasting antinociceptive effects in surgical pain and inflammatory pain models [19, 80]. It is currently unclear why Loram and colleagues observed enduring antinociceptive effects with very low doses of CGS21680 while others observed no or short lasting antinociceptive effects in three different pain models with much higher doses of CGS21680.

In addition, A2AR activation significantly reduced microglial and astroglial activation and elevated the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-10. Nerve injury activates microglial cells, which contribute to the maintenance of neuropathic pain [41]. A2AR activation might —reset microglial cells to a quiescent state. Interestingly, microglial cells express A2AR only when activated [81], which could explain why A2AR agonists had enduring antinociceptive effects in neuropathic animals but not in naïve animals [78]. These findings might also explain why adenosine receptor activation has long lasting (days to months) pain-relieving effects in some neuropathic pain patients [5]. In patients who did not experience long-lasting relief, the dose of adenosine might have been too low or too high to appropriately activate A2AR. Alternatively, A2AR-expressing microglia might not contribute to pain in some patients. More trials are certainly warranted in neuropathic pain patients with additional intrathecal doses of adenosine and/or with A2AR agonists.

Concluding remarks

Previous efforts aimed at treating pain with adenosine have failed, and cardiovascular side effects (Box 1) negate the use of full A1R agonists in pill form (systemic delivery). However, in no way do these failures negate the use of other routes of administration, more creative drug design, use of ectonucleotidases or use of partial agonists, such as those that appear to be safe when administered systemically in humans (Box 1). There is no question that adenosine receptors have been validated in the setting of chronic pain [5], although whether these receptors inhibit spontaneous pain in humans is still an open question (Box 3). The recent findings linking adenosine to the antinociceptive effects of acupuncture in mice suggest that peripheral engagement of A1R could underlie the pain-relieving effects of this procedure in humans. Localized activation of adenosine receptors, either spinally or in peripheral tissues, might be the key to unlocking the therapeutic potential of these receptors. Localized activation could minimize or eliminate cardiovascular side effects when compared to systemic drug delivery while providing non-addictive treatment options for patients with chronic pain.

Box 3. Outstanding Questions.

Does caffeine block the pain-relieving effects of acupuncture in humans?

Can the pain-relieving effects of acupuncture be extended by pharmacologically blocking adenosine metabolism?

Do partial A1R agonists (delivered orally) inhibit pain in humans with minimal side effects?

Can A1R agonists or recombinant ectonucleotidases inhibit pain in humans if injected locally, via spinal route or in the periphery near sensory nerve bundles?

Do A1R agonists or recombinant ectonucleotidases have preemptive analgesic effects in humans?

As has been shown for an adenosine-generating ectonucleotidase [24], is thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia enduringly reduced if an A1R agonist is administered before and during nerve injury or inflammation?

Will a selective A2AR agonist (delivered intrathecally) enduringly reverse the symptoms of neuropathic pain in humans?

Which additional ectonucleotidases hydrolyze ATP, ADP and AMP in nociceptive circuits?

Will pharmaceutical companies report their proprietary data related to adenosine receptor agonists so that more informed clinical trials can be performed?

Acknowledgments

I thank Julie Hurt and Sarah Street for comments. This work was supported by grants from NINDS (R01NS060725, R01NS067688).

Glossary Box

- Allodynia

pain caused by a stimulus that is not normally painful. As an example, clothing hurts when it rubs against sunburned skin

- Antinociceptive

inhibition of behaviors associated with or caused by noxious stimuli or sensitization. Examples of nociceptive behavior includes hindpaw withdrawal, foot licking or shaking, paw guarding

- Ectonucleotidases

secreted or membrane-bound enzymes that dephosphorylate extracellular nucleotides (ATP, ADP and/or AMP)

- Equilibrative nucleoside transporters

this family includes ENT1-4 (also known as SLC29A1-4) and transports adenosine into or out of cells depending on the relative intracellular and extracellular adenosine concentration. For example, adenosine is transported outside the cell through these transporters if the intracellular adenosine concentration is higher than the extracellular concentration

- Hyperalgesia

increased sensitivity to an already noxious stimulus. As an example, a hot shower hurts more when skin is sunburned

- NT5E

ecto-5’-nucleotidase (also called CD73) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane protein that generates adenosine extracellularly by dephosphorylating AMP. αβ-methylene-ADP is a commonly used inhibitor of NT5E [82] and does not inhibit PAP [53]

- P2 purinergic receptors

divided into P2X and P2Y families based on distinct molecular structures and pharmacology. P2X receptors are a family of two-transmembrane ligand-gated ion channels and can be activated by ATP. P2Y receptors are a family of seven transmembrane GPCRs that can be activated by ATP, ADP and other nucleotides

- PAP

prostatic acid phosphatase, an ectonucleotidase that dephosphorylates extracellular AMP at neutral and acidic pH. PAP can also dephosphorylate ATP and ADP at acidic pH [58]. There is a secreted and a transmembrane isoform of PAP [47, 83]. Both isoforms are derived from the same gene product but are produced from alternatively spliced transcripts. A cytoplasmic (—cellular ) isoform of PAP has also been described [84]; however, there is no direct empirical evidence to support the existence of this isoform (http//www.cell.com/neuron/comments/S0896-6273(08)00750-2)

- Preemptive analgesic

a drug that when administered shortly before and during surgery has the ability to reduce postoperative pain and the need for postoperative analgesics. Recent data with rodents suggests the timing of A1R activation relative to injury/inflammation is critical to achieve preemptive analgesia

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–64. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulte G, et al. Distribution of antinociceptive adenosine A1 receptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn, and relationship to primary afferents and neuronal subpopulations. Neuroscience. 2003;121:907–16. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reppert SM, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rat A1-adenosine receptor that is widely expressed in brain and spinal cord. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1037–48. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-8-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima FO, et al. Direct blockade of inflammatory hypernociception by peripheral A1 adenosine receptors: Involvement of the NO/cGMP/PKG/KATP signaling pathway. Pain. 2010;151:506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawynok J. Adenosine and ATP receptors. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;177:309–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-33823-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashida M, et al. Clinical application of adenosine and ATP for pain control. J Anesth. 2005;19:225–35. doi: 10.1007/s00540-005-0310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch ME, et al. Intravenous adenosine alleviates neuropathic pain: a double blind placebo controlled crossover trial using an enriched enrolment design. Pain. 2003;103:111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsten R, Gordh T., Jr An A1-selective adenosine agonist abolishes allodynia elicited by vibration and touch after intrathecal injection. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:844–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199504000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenach JC, et al. Intrathecal but not intravenous opioids release adenosine from the spinal cord. J Pain. 2004;5:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind G, et al. Drug-enhanced spinal stimulation for pain: a new strategy. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:57–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-33079-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Direct cutaneous hyperalgesia induced by adenosine. Neuroscience. 1990;38:757–62. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90068-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backonja MM, Stacey B. Neuropathic pain symptoms relative to overall pain rating. J Pain. 2004;5:491–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King T, et al. Unmasking the tonic-aversive state in neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1364–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolphin AC, et al. Calcium-dependent currents in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurones are inhibited by an adenosine analogue. J Physiol. 1986;373:47–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mynlieff M, Beam KG. Adenosine acting at an A1 receptor decreases N-type calcium current in mouse motoneurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3628–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03628.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidtko A, et al. Ziconotide for treatment of severe chronic pain. Lancet. 2010;375:1569–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin TJ, et al. Opioid self-administration in the nerve-injured rat: relevance of antiallodynic effects to drug consumption and effects of intrathecal analgesics. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:312–22. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200702000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenach JC, et al. Intrathecal, but not intravenous adenosine reduces allodynia in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain. 2003;105:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zahn PK, et al. Adenosine A1 but not A2a receptor agonist reduces hyperalgesia caused by a surgical incision in rats: a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein-dependent process. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:797–806. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000286982.36342.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basbaum AI, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009;139:267–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langford DJ, et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat Methods. 2010;7:447–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gan TJ, Habib AS. Adenosine as a non-opioid analgesic in the perioperative setting. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:487–94. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000267260.00384.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habib AS, et al. Phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial of intravenous adenosine for perioperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:1085–91. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818db88c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sowa NA, et al. Prostatic acid phosphatase reduces thermal sensitivity and chronic pain sensitization by depleting phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10282–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2162-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji RR, et al. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:135–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuka Y, et al. Altered ATP release and metabolism in dorsal root ganglia of neuropathic rats. Mol Pain. 2008;4:66. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon CJ, et al. Regulation of epidermal homeostasis through P2Y2 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1680–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koizumi S, et al. Ca2+ waves in keratinocytes are transmitted to sensory neurons: the involvement of extracellular ATP and P2Y2 receptor activation. Biochem J. 2004;380:329–38. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura F, Strittmatter SM. P2Y1 purinergic receptors in sensory neurons: contribution to touch-induced impulse generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10465–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gourine AV, et al. Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP. Science. 2010;329:571–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1190721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arcuino G, et al. Intercellular calcium signaling mediated by point-source burst release of ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9840–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152588599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin JH, et al. A central role of connexin 43 in hypoxic preconditioning. J Neurosci. 2008;28:681–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3827-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang J, et al. Connexin 43 hemichannels are permeable to ATP. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4702–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabirov RZ, Okada Y. ATP release via anion channels. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:311–28. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-1557-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawada K, et al. Identification of a vesicular nucleotide transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5683–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800141105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fields RD, Ni Y. Nonsynaptic communication through ATP release from volume-activated anion channels in axons. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra73. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sreedharan S, et al. Glutamate, aspartate and nucleotide transporters in the SLC17 family form four main phylogenetic clusters: evolution and tissue expression. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann H. Ectonucleotidases in the nervous system. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;276:113–28. discussion 128–30, 233–7, 275–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunwiddie TV, et al. Adenine nucleotides undergo rapid, quantitative conversion to adenosine in the extracellular space in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7673–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07673.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakagawa T, et al. Intrathecal administration of ATP produces long-lasting allodynia in rats: differential mechanisms in the phase of the induction and maintenance. Neuroscience. 2007;147:445–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuda M, et al. Neuropathic pain and spinal microglia: a big problem from molecules in "small" glia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gereau RWt, Conn PJ. Potentiation of cAMP responses by metabotropic glutamate receptors depresses excitatory synaptic transmission by a kinase-independent mechanism. Neuron. 1994;12:1121–9. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brundege JM, et al. The role of cyclic AMP as a precursor of extracellular adenosine in the rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1201–10. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sawynok J, Liu XJ. Adenosine in the spinal cord and periphery: release and regulation of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:313–40. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kowaluk EA, Jarvis MF. Therapeutic potential of adenosine kinase inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:551–64. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGaraughty S, et al. Anticonvulsant and antinociceptive actions of novel adenosine kinase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:43–58. doi: 10.2174/1568026053386845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zylka MJ, et al. Prostatic acid phosphatase is an ectonucleotidase and suppresses pain by generating adenosine. Neuron. 2008;60:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor-Blake B, Zylka MJ. Prostatic acid phosphatase is expressed in peptidergic and nonpeptidergic nociceptive neurons of mice and rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sowa NA, et al. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) inhibits nociception by hydrolyzing AMP to adenosine in nociceptive circuits. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2235–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5324-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sweeney MI, et al. Morphine, capsaicin and K+ release purines from capsaicin-sensitive primary afferent nerve terminals in the spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:447–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torres IL, et al. Effect of chronic and acute stress on ectonucleotidase activities in spinal cord. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patterson SL, et al. A novel transverse push-pull microprobe: in vitro characterization and in vivo demonstration of the enzymatic production of adenosine in the spinal cord dorsal horn. J Neurochem. 2001;76:234–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sowa NA, et al. Recombinant ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) has long lasting antinociceptive effects that are dependent on adenosine A1 receptor activation. Mol Pain. 2010;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu WP, et al. Increased nociceptive response in mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor. Pain. 2005;113:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keil GJ, 2nd, DeLander GE. Altered sensory behaviors in mice following manipulation of endogenous spinal adenosine neurotransmission. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;312:7–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian L, et al. Excitatory synaptic transmission in the spinal substantia gelatinosa is under an inhibitory tone of endogenous adenosine. Neurosci Lett. 2010;477:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rozisky JR, et al. Neonatal morphine exposure alters E-NTPDase activity and gene expression pattern in spinal cord and cerebral cortex of rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;642:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sowa NA, et al. Recombinant mouse PAP has pH-dependent ectonucleotidase activity and acts through A(1)-adenosine receptors to mediate antinociception. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zimmermann H. Prostatic acid phosphatase, a neglected ectonucleotidase. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:273–5. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9157-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Millan JL. Alkaline Phosphatases : Structure, substrate specificity and functional relatedness to other members of a large superfamily of enzymes. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:335–41. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vihko P, et al. Secretion into and elimination from blood circulation of prostate specific acid phosphatase, measured by radioimmunoassay. J Urol. 1982;128:202–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52818-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams JA, et al. Ziconotide: an update and review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1575–83. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.9.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Post C. Antinociceptive effects in mice after intrathecal injection of 5′-N-ethylcarboxamide adenosine. Neurosci Lett. 1984;51:325–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sklar SH, et al. Herpes zoster. The treatment and prevention of neuralgia with adenosine monophosphate. JAMA. 1985;253:1427–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.253.10.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.El-Tayeb A, et al. Nucleoside-5′-monophosphates as Prodrugs of Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Agonists Activated by ecto-5′-Nucleotidase (dagger) dagger Contribution to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Division of Medicinal Chemistry of the American Chemical Society. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7669–7677. doi: 10.1021/jm900538v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyer JL, et al. Identification of potent P2Y-purinoceptor agonists that are derivatives of adenosine 5′-monophosphate. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1959–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malin SA, Molliver DC. Gi- and Gq-coupled ADP (P2Y) receptors act in opposition to modulate nociceptive signaling and inflammatory pain behavior. Mol Pain. 2010;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J, et al. Constant darkness is a circadian metabolic signal in mammals. Nature. 2006;439:340–3. doi: 10.1038/nature04368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Daniels IS, et al. A role of erythrocytes in adenosine monophosphate initiation of hypometabolism in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20716–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swoap SJ, et al. AMP does not induce torpor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R468–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00888.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao ZQ. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;85:355–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ernst E. Acupuncture: what does the most reliable evidence tell us? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:709–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldman N, et al. Adenosine A1 receptors mediate local anti-nociceptive effects of acupuncture. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:883–888. doi: 10.1038/nn.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aley KO, Levine JD. Multiple receptors involved in peripheral alpha 2, mu, and A1 antinociception, tolerance, and withdrawal. J Neurosci. 1997;17:735–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu C, et al. Involvement of purines in analgesia produced by weak electro-acupuncture. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 1994;19:59–62. 54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zylka MJ. Needling adenosine receptors for pain relief. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:783–4. doi: 10.1038/nn0710-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rohacs T, et al. Phospholipase C mediated modulation of TRPV1 channels. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;37:153–63. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8027-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Loram LC, et al. Enduring reversal of neuropathic pain by a single intrathecal injection of adenosine 2A receptor agonists: a novel therapy for neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14015–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3447-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee YW, Yaksh TL. Pharmacology of the spinal adenosine receptor which mediates the antiallodynic action of intrathecal adenosine agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1642–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Poon A, Sawynok J. Antinociception by adenosine analogs and inhibitors of adenosine metabolism in an inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia model in the rat. Pain. 1998;74:235–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Orr AG, et al. Adenosine A(2A) receptor mediates microglial process retraction. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:872–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Colgan SP, et al. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Quintero IB, et al. Prostatic acid phosphatase is not a prostate specific target. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6549–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Veeramani S, et al. Cellular prostatic acid phosphatase: a protein tyrosine phosphatase involved in androgen-independent proliferation of prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:805–22. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kiesman WF, et al. A1 adenosine receptor antagonists, agonists, and allosteric enhancers. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;193:25–58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89615-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schaddelee MP, et al. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling of the anti-hyperalgesic and anti-nociceptive effect of adenosine A1 receptor partial agonists in neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;514:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van Schaick EA, et al. Selectivity of action of 8-alkylamino analogues of N6-cyclopentyladenosine in vivo: haemodynamic versus anti-lipolytic responses in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:607–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maier SA, et al. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a novel protein family closely related to adenosine deaminase. J Mol Evol. 2005;61:776–94. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0046-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Iijima R, et al. The extracellular adenosine deaminase growth factor, ADGF/CECR1, plays a role in Xenopus embryogenesis via the adenosine/P1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2255–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zavialov AV, Engstrom A. Human ADA2 belongs to a new family of growth factors with adenosine deaminase activity. Biochem J. 2005;391:51–7. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Magalhaes-Cardoso MT, et al. Ecto-AMP deaminase blunts the ATP-derived adenosine A2A receptor facilitation of acetylcholine release at rat motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 2003;549:399–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Golembiowska K, et al. Modulation of adenosine release from rat spinal cord by adenosine deaminase and adenosine kinase inhibitors. Brain Res. 1995;699:315–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00926-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parkinson FE, Geiger JD. Effects of iodotubercidin on adenosine kinase activity and nucleoside transport in DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sinclair CJ, et al. Nucleoside transporter subtype expression: effects on potency of adenosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1037–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]