Abstract

Objective

To examine the effects of a multi-component, theory-based, 2.5-year intervention on children’s fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption, preferences, knowledge and body mass index (BMI).

Methods

Four inner city elementary schools in the Northeastern United States were randomized to an intervention (n = 149) or control group (n = 148) in 2005. F&V consumption during school lunch (measured by plate waste), preferences, and knowledge, as well as BMI were assessed five times across 3.5 years (pre-intervention, spring 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009). Hierarchical linear modeling was used to analyze program outcomes.

Results

At the first post-test assessment, children in the experimental group ate 0.28 more servings/lunch of F&V relative to children in the control group and changes in F&V consumption were found in each year throughout the program. However, this effect declined steadily across time so that by the delayed one-year follow-up period there was no difference between the groups in F&V consumption. There were persistent intervention effects on children’s knowledge. There were no effects on F&V preferences and BMI throughout the study.

Conclusion

Although there was initial F&V behavior change, annual measurements indicated a gradual decay of behavioral effects. These data have implications for the design of school-based F&V interventions.

Introduction

Many research teams have evaluated school-based fruit and vegetable (F&V) interventions. In a systematic review Knai et al. (2006) reported on nine studies that focused on elementary school-age children. Seven of the nine demonstrated significant improvements in children’s consumption as a result of school-based interventions with effects ranging from 0.30 to 0.99 servings/day. Additionally, Howerton et al. (2007) conducted a pooled analysis across seven school-based studies and found on average children in intervention groups ate 0.45 more servings of F&V relative to children in the control groups. While the duration of the intervention and evaluation tends to be one school year for most studies, a few programs describe an intervention that was provided to the same group of students across multiple years (Baranowski et al., 2000; Perry et al., 2004; Nicklas, 1998; Gortmaker et al., 1999a; Gortmaker et al., 1999b; Lytle et al., 2004). Only one of these multi-year intervention studies examined changes in students eating behaviors annually (Nicklas, 1998). In this study the population was adolescents and the final data collection phase occurred soon after the intervention was withdrawn. The majority of studies only use a pre-test/post-test evaluation design without an extended follow-up and children’s F&V consumption is assessed mostly by self-report rather than observation (Knai et al., 2006).

The current study was designed to add to the existing literature in three ways by: (1) examining annual changes in children’s F&V consumption, preferences, knowledge, and body mass index (BMI) in response to exposure to a multi-year, multi-component, theory-based intervention; (2) obtaining follow-up data one year after the intervention was withdrawn; and (3) measuring F&V consumption objectively using weighed plate waste. Plate waste is rarely used because it is time consuming; however, it provides one of the most precise measures of children’s consumption (Kirks & Wolff, 1985). It was hypothesized that children who received the intervention would demonstrate increased F&V knowledge, preferences and lunchtime consumption and lower BMI relative to a comparison group who did not receive the intervention. Additionally, it was hypothesized that the intervention effects would persist over time through the follow-up period. The primary dependent variable in this study was F&V consumption. The intervention was designed so that children were encouraged to eat more F&V. It was hypothesized that preferences for these foods would increase with repeated exposures (Birch & Marlin, 1982). Additionally, children received new information in an engaging format so knowledge was hypothesized to increase. BMI was included as a dependent variable for exploratory purposes.

Methods

Subjects

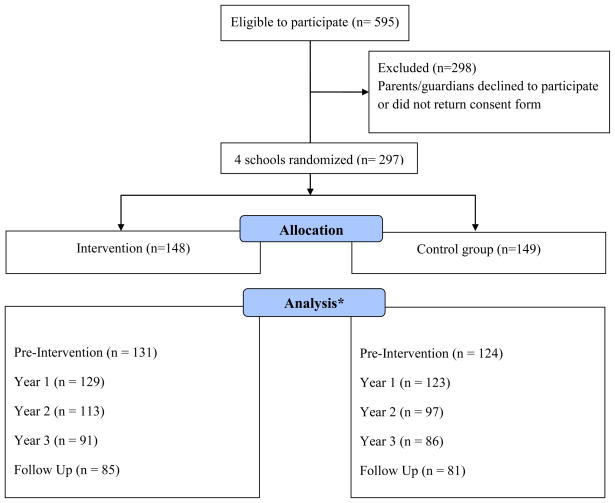

Kindergarten and first grade children (N = 297), who attended four inner city public schools from the same school district, participated in this study (experimental group = 149; control group = 148; see Figure 1). Most children were African American or Latino/a and received free or reduced price lunch. Baseline characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. All kindergarten and first grade students during the 2004–2005 and 2005–2006 school years were eligible to participate. Signed parental consent was required for inclusion in the program evaluation. Multiple approaches were used to obtain recruit participants (e.g., teacher meetings, principal support, classroom presentations, a motivational system to encourage bringing back forms; Blom-Hoffman et al., 2009) resulting in participation rates of 56% and 45% across the experimental and control groups, respectively.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participant progress through the phases of the study (Northeastern United States; 2005–2009).

Note: *The sample size represents the number of participants with either or both of the main outcome measures (F&V intake) available at each study phase. Only data from students who ate the school lunch were collected and analyzed. In each study phase this included > 95% of students in both groups. Almost all children were lost to follow up because they moved to another school.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information by Group (Baseline Data 2005, Northeastern U.S.)

| Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experimental (n = 149) | Control (n = 148) | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 6.2 (0.53) | 6.2 (0.60) |

| Gender (boys) | 51% | 51% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 29% | 36% |

| Latino | 41% | 51% |

| Asiana | 24% | 0% |

| White | 3% | 4% |

| Other | 2% | 9% |

| Children eligible for free or reduced price lunch | 94% | 88% |

| BMI-for-age z-score at pre-intervention | 0.80 (1.13) | 0.93 (1.07) |

Note.

Groups are significantly different.

Intervention description and monitoring

The 2.5-year program was based in social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), and included school-wide (daily loud speaker announcements), classroom (instructional DVD), lunchroom (daily stickers contingent on a bite of fruit or vegetable), and family (take-home activity books) components to promote F&V consumption with an emphasis on F&V in the school lunch (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008a; Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008b; Hoffman et al., 2010). Consistent with social learning theory, program components were designed to capture students attention and to increase retention of F&V nutrition information by having a variety of influential role models (i.e., the school principal, coaches, cartoon characters, videos with same age peers) deliver consistent information across multiple settings. The program was designed to: (a) include repetition of messages across settings, modalities, and messengers; (b) use symbolic and live role modeling; (c) incorporate vicarious and direct reinforcement; and (d) be implemented entirely by school staff. Unannounced observations, staff-completed logs and student interviews were used to assess implementation fidelity. Implementation data have been described previously (Hoffman et al., 2010). Overall, fidelity data indicated that intervention components designed to be implemented daily were implemented on the majority of school days at both schools across the 2.5 years of intervention. The classroom DVD was implemented as intended in Years 1 and 2 and rarely in Year 3.

Instruments

Four measures were used to evaluate the intervention: (a) weighed plate waste; (b) F&V preference questionnaire; (c) F&V knowledge questionnaire; and (d) BMI. Each was collected from participants at school on five occasions (see Table 2): winter 2006 (“Pre-intervention”), spring 2006 (“Year 1”), spring 2007 (“Year 2”), spring 2008 (“Year 3”) and spring 2009 (“Follow-Up”). Child race and ethnicity were obtained from caregivers who participated in a phone interview in their native language by a native speaker.

Table 2.

Timing of Assessments and Intervention Delivery (2005–2009; Northeastern United States)

| Sp ‘05 | F ‘05 | W ‘06 | Sp ‘06 | F ‘06 | W ‘07 | Sp ‘07 | F ‘07 | W ‘08 | Sp ‘08 | F ‘08 | W ‘09 | Sp ‘09 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | ||||||||||||||

| Assessment | Bsln | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | F/U | |||||||||

| Intervention | 25 months |

Weighed plate waste

Procedures for assessing children’s lunchtime F&V consumption using weighed plate waste have been described in detail previously (Hoffman et al., 2010). All four schools used the same school lunch menus and portion sizes were similar across the schools. Assessments were conducted in the cafeterias on three days in each school during each data collection phase, so that a total of 60 days of data were collected across the study. Only foods served in the school lunch were measured. Vegetables included steamed green vegetables, steamed corn, and raw vegetables (salad or carrot sticks). Fruits were canned and fresh. Before children began eating three sample portions of each food were measured to determine the average portion size. After lunch food was weighed on a food scale that was accurate to 1 gram (Salter Model 2006, Kent, England). Each student’s remaining portion of fruit and vegetable was weighed separately. Trained research assistants (RAs), blind to study purposes, hypotheses and group assignments, observed children throughout the lunch period and collected trays. All children wore nametags. To assess reliability, two independent RAs simultaneously observed 24% of students across the study. Kappa coefficients for fruits (range = 0.69–0.92) and vegetables (range = 0.86–1.00) ranged from “moderate” to “almost perfect” agreement. Food intake was calculated as follows: Initial mean portion served in grams minus uneaten food in grams. Food and Drug Administration average servings sizes for fruit (140 g) and vegetables (85 g) were used to calculate changes in consumption in terms of serving size (Eldridge et al., 1998).

F&V preferences

Child-reported F&V preferences were assessed using an adapted Fruit and Vegetable Preference Questionnaire (A-FVPQ; Hoffman et al., 2010). The A-FVPQ consisted of 20 items (11 fruits; 9 vegetables). Students were shown a picture of each food item and asked to report how much they liked the food using a pictorial response scale (0=not at all, 1=a little, and 2=a lot). Scores on the fruit scale ranged from 0 to 22, and scores on the vegetable scale ranged from 0 to 18.

F&V knowledge

Children’s F&V knowledge was assessed using a 9-item instrument comprised of open-ended (n = 4) and multiple choice (n = 5) questions. Items were developed by the first author and included information highlighted in the intervention. To assess content validity a panel of five nutrition experts rated a pool of items on importance and age appropriateness. Next, the items were tested with a separate sample of 60 children in kindergarten through 4th grade to examine item difficulty level and 2-week, test-retest reliability. The items selected for the final version of the instrument varied in difficulty level and the test-retest correlations across the grade levels were moderately strong (r = 0.58–0.62).

Body mass index

The lead author measured children’s height and weight at school. Children removed shoes and sweaters prior to measurement. Systematic anthropometric techniques followed those described by Lohman et al. (1988). Weight was measured to 0.1 kg (Seca digital electronic scale, Creative Health Products, Plymouth, MI). Standing height was measured to 0.1 cm with a portable stadiometer (Shorr Productions, Olney, MD). BMI-for-age z-scores were calculated with EpiInfo (Dean et al., 2007), using normative data from the CDC 2000 reference growth charts (Ogden et al., 2002).

Child acceptability of intervention components

Children used a 3-point pictorial rating scale (☹= does not like; ☺ = likes a little; ☺☺ = likes a lot) to respond to questions assessing their perceptions of program components that were designed to be implemented daily (i.e., lunchtime stickers and morning announcements) in Years 2 and 3 (Hoffman et al., 2010).

Procedure

Study design

Among the four schools, the first author randomly chose two to participate in the intervention group and two to participate in the control group. The study design was longitudinal with measurements collected annually across five points. The intervention was implemented continuously across 2.5 school years (25 months) from February 2006 through June 2008. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northeastern University and by the school district’s research office.

Power calculations

Power calculations were conducted using Nquery Advisor 4.0 software. The assumptions used for sample size estimation were: Type I error of 5% (2-sided); 80% power or above to compare the difference between the intervention group and control group; equal number of students assigned to intervention and control groups. Data from a pilot study (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2004) were used to estimate the difference in F&V consumption between students in the intervention and control groups after the first year of program implementation. The pilot study measured plate waste with visual estimates, using the ordinal 6-point Comstock scale (Dubois, 1990; 5=91–100%; 4=76–90%; 3=51–75%; 2=26–50%; 1=11–25%; 0=0–10%) and found a 1.1 point difference on the scale (d = 0.61) from pre- to post- intervention. The study was powered to detect group differences in percent plate waste, whereas the analyses reported in this paper focused on grams of F&V consumed. However, given that grams consumed is closely associated with percent plate waste (r=−0.92 for fruit, r=−0.91 for vegetables at baseline, and based on scatterplots, it was clear that grams consumed was close to being a linear function of percent plate waste), power to detect group differences in grams consumed should be very similar to power to detect group differences in percent plate waste.

Statistical analyses

In this study, students were nested within schools and data were collected for each student at multiple time points. Analyses were conducted at the time point (within-student) level, taking into account the repeated measurements within students. School was treated as a fixed effect (i.e., differences among school means were modeled) rather than as a random effect (modeling the correlation among students within schools), due to the small number of schools, making it unlikely that random school effects could be accurately estimated (Brown & Prescott, 1999). Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used to analyze the data, due to the ability of HLM to accommodate repeated measures and to handle missing data that are typical in longitudinal analyses (Beunckens et al., 2005; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000). A separate model was constructed for the amount of fruit consumed (intake in grams/lunch) and the amount of vegetables consumed (intake in grams/lunch). Group differences in each measure Yij (i denotes yearly measures within students and j denotes students) after the intervention (Years 1, 2, and 3 and Follow-Up) were modeled as follows:

In the model equation, β0j is an intercept term, β1 is the estimated effect of group and β2 through βn represent the estimated effects of a set of adjustment variables, specifically the dependent variable measured at pre-intervention and sex, race/ethnicity, BMI z-score, F&V preference, and school. Model estimates are interpreted as estimated fruit/vegetable consumption in Year 1 through Follow-Up after statistically controlling for differences in the amount consumed at pre-intervention and the other adjustment variables. Models with a similar structure were also constructed for F&V preferences, knowledge scores and BMI-for-age z-scores (BMI not measured in post-intervention Year 1).

There were missing data at pre-intervention and follow-up time points. Multiple imputation (PROC MI and MIANALYZE in SAS) was selected to handle missing data (Tang et al, 2005). The missing at random (MAR) assumption required for multiple imputation seemed plausible, because missingness was primarily caused by absenteeism and students transferring to different schools.

Diagnostics indicated that all models were reasonably consistent with statistical assumptions. The amount of fruit consumed was compared with the amount of vegetables consumed using paired t-tests, a separate test for each study year. All tests of significance were one-sided (hypotheses: experimental > control for fruit and vegetable intake and preferences and knowledge scores, experimental < control for BMI) and performed at the α = 0.05 level. The intra-class correlation (ICC) is reported as an estimate of the proportion of the variance in F&V consumption that was between as opposed to within students (ICC = τ00/(τ00 + σ2); Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992), after taking the adjustment variables into account. Cohen’s d, interpreted as the standardized difference between groups, was used as an indicator of effect sizes (d values around 0.2 have been considered “small,” 0.5 are “medium,” and 0.8 are “large”; Cohen, 1988).

Results

Group differences in fruit and vegetable consumption

Means for the F&V consumption measures by study group and year are shown in Table 3. Preliminary analyses showed that at pre-intervention, the groups differed only on vegetable intake, which was about 3 g/lunch greater among children in the experimental group (p<0.05). All remaining analyses examining group differences statistically controlled for F&V intake at pre-intervention.

Table 3.

Mean (95% CI) for Measures of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Grams by Study Group and Year

| Consumption measure | Group | Pre-intervention | Study Year | Follow-Up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

| Fruit intake, gram/lunch | Experimental | 28 (23, 33) | 45 (40, 50)*** | 34 (30, 39)*** | 33 (29, 38) | 30 (26, 34) |

| Control | 28 (22, 33) | 27 (22, 32) | 23 (18, 28) | 32 (28, 37) | 34 (29, 39) | |

| Vegetable intake, gram/lunch | Experimental | 11** (9, 13) | 17 (15, 20)*** | 15 (12, 17)* | 16 (13, 19)* | 14 (11, 16) |

| Control | 9 (7, 10) | 8 (6, 10) | 8 (6, 10) | 11 (8, 13) | 12 (9, 14) | |

Notes. (1) Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data. All available data from all time points were utilized to impute the missing data. Because more data were available in the present analysis (5 waves) than in the prior analysis (3 waves, Hoffman et al, 2010), this caused slight changes in some of the reported estimates, but in no case did this alter the statistical significance or direction of the reported differences. (2) Significant differences between the experimental and control groups are noted as follows:

p<0.001

p<0.05

p<0.10.

(3) This study was conducted in the Northeastern United States. All data were collected between 2005–2009.

Children in the experimental group consumed more fruit compared with children in the control group in Years 1 and 2 of the program. In Year 1 children in the experimental group consumed 22 more grams of fruit per lunch (95% CI: 14 – 30 g, p<0.0001, Cohen’s d=0.69, ICC = 0.12; 0.21 serving/lunch) compared with children in the control group. In Year 2, children in the experimental group consumed 15 more grams of fruit per lunch (95% CI: 6 – 23 g, p<0.0005, Cohen’s d=0.49; 0.15 serving/lunch) compared with children in the control group. In Year 3 and Follow-Up, the children in the experimental group did not consume more fruit than children in the control group, p>0.05 (experimental minus control fruit intake, Year 3=4 g, 95% CI: −5 – 13 g; Follow-Up = −1 g, 95% CI: −9 – 7 g).

In Year 1 children in the experimental group consumed 7 more grams of vegetables per lunch (95% CI: 3 – 10 g, p<0.005, Cohen’s d=0.47, ICC=0.18; 0.07 servings/lunch) compared with children in the control group. In Year 2, children in the experimental group consumed 3 more grams of vegetables per lunch (95% CI: −0.5 – 6.5 g, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.24, 0.04 servings/lunch) compared with children in the control group. In Year 3, children in the experimental group again consumed 3 more grams of vegetables per lunch (95% CI: −0.2 – 6.7 g, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.28; 0.04 servings/lunch) compared with the control group. However, at Follow-Up, children in the experimental group did not consume more vegetables than children in the control group, p>0.05 (experimental minus control vegetable intake = 0 g, 95% CI: −4 – 5 g).

Changes in intake of F&V in the control group over time were examined (Year 1 vs. Year 2, Year 1 vs. Year 3, Year 1 vs. Follow-Up). For fruit intake, in the control group, intake increased significantly between Year 1 and Follow-Up (p s<0.05); for vegetable intake, in the control group, intake increased significantly between Years 1 and 3, and also between Year 1 and Follow-Up (p s<0.05).

Group differences in student F&V preferences

Students fruit preferences were higher than their vegetable preferences across all five time points, and preferences were remarkably stable across time (fruit preference range M=18.0–19.2; SD=2.2–3.5; vegetable preference range M=10.8–11.8; SD=2.4–3.4). After adjusting for pre-intervention fruit and vegetable preferences, the experimental group did not express greater preference for fruit than the control group in any post-intervention year, p>0.05 (experimental minus control fruit preference, Year 1 = −0.12, 95% CI: −0.85, 0.61; Year 2 = 0.33, 95% CI: −0.49 – 1.14; Year 3 = −0.19, 95% CI: −1.09 – 0.71; Follow-Up = 0.26, 95% CI: −0.64 – 1.17), nor did the experimental group express greater preference for vegetables than the control group in any post-intervention year, p>0.05 (experimental minus control vegetable preference, Year 1 = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.92 – 0.75; Year 2 = −0.05, 95% CI: −0.91–0.81; Year 3 =−0.54, 95% CI: −1.36 – 0.29; Follow-Up = −0.05, 95% CI: −1.16 – 1.05).

Group differences in student knowledge

During every post-intervention year, knowledge scores for experimental group children were about one-half to two-thirds of a point greater than knowledge scores for control group children, p<0.05 (experimental minus control knowledge scores, Year 1: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.01 – 0.96, p<0.05, Cohen’s d= 0.25; Year 2: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.004 – 1.02, p<0.05, Cohen’s d= 0.28; Year 3: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.09 – 1.25, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.36; Follow-Up: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.03 – 0.95, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.34).

Group differences in body mass index (BMI)

BMI was measured at Pre-intervention and in Years 2 and 3 and at Follow-Up. BMI-forage z-scores for experimental group children did not differ from those for control group children during any post-intervention year, p>0.05 (experimental minus control BMI-for-age z-scores, Year 2: 0.07, 95% CI: −0.11 – 0.24; Year 3: 0.08, 95% CI: −0.15 – 0.31; Follow-Up: 0.16, 95% CI: −0.06 – 0.37).

Child acceptability

Across Years 2 and 3 most children reported lunchtime stickers helped them eat their F&V at lunch “a lot” (Year 2=87%; Year 3=66%) and that they liked the stickers “a lot” (Year 2=73%; Year 3=66%). In both years, 78% of children reported liking the morning announcements “a lot.”

Discussion

This study was a controlled evaluation of a multi-year, multi-component, theory-based F&V intervention, implemented with young children across 2.5 school years, and evaluated annually to examine incremental changes in F&V consumption, preference, knowledge, and BMI. Consistent with interventions that yielded dietary improvements (Sahay et al., 2006) and interventions that were effective in reducing childhood obesity (Cole et al., 2006), the intervention in this study was grounded in social learning theory (Blom-Hoffman, 2008), engaged the family (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008), used a participatory model, delivered a clear message, and provided sufficient training and on-going support to school personnel. To our knowledge it represents the first evaluation of a multi-year F&V promotion intervention that tracked yearly program effects with young children. The study design included a delayed follow-up one year after intervention withdrawal. The primary dependent variable, F&V consumption, was measured using weighed plate waste, providing a precise estimate of children’s eating behavior. Results indicated that after the first five months of intervention, children in the experimental group ate 0.28 more servings/lunch of F&V compared with children in the control group. After 15 months of intervention, the intervention effect diminished to 0.19 additional F&V servings/lunch. After 25 months of intervention and at the delayed follow-up there was no difference between the two groups, except for a small difference in vegetable consumption in Year 3. Additionally, there were unexpected increases in F&V consumption among students in the control group over time. The reasons for this unexpected effect are unclear given that no other school-wide F&V initiatives were implemented during this time in the control schools. Children who received the intervention did demonstrate small increases in knowledge relative to the control group, which persisted over time. There were no intervention-related effects on children’s F&V preferences or BMI.

The initial findings from the end of Year 1 are somewhat consistent with other studies (Knai et al., 2006; Howerton et al., 2007); the slightly lower difference found in the current study may be a function of the more accurate plate waste methodology used and the assessment of lunchtime-only consumption. Beyond Year 1 a steady decay of the intervention’s effect was observed. Interestingly, the only other study that evaluated annual changes in students consumption over multiple years similarly found significant improvements in F&V consumption after two years of intervention, which were not observed by the end of the third intervention year (Nicklas et al., 1998). Together, these two studies demonstrate that initial pre-post gains in students F&V consumption are difficult to maintain over a longer period of time.

It is unclear why the behavioral findings decayed in the current study. Two possibilities are that the intervention was better suited for younger children or that students became bored with it. Student-reported acceptability of the lunchtime component declined over time, so perhaps students were less motivated to earn a sticker from lunch monitors as they got older. Indeed, the Year 3 findings indicated that students ate just enough of their vegetable to earn a sticker. This issue raises important questions for future research regarding the necessary dose of an intervention over time to yield enduring behavior change.

Although this study did not demonstrate sustained changes in behavior, there were significant changes in knowledge that were maintained throughout the study. Nicklas et al. (1998) also found that knowledge change persisted despite the lack of sustained behavior change. This finding makes sense given that students should not forget information they learned previously, and these enduring knowledge gains may be helpful over time.

Surprisingly, children’s F&V preferences remained remarkably stable across the intervention. Unlike a prior study that modified the F&V served and then showed improvements in children’s F&V preferences (Weber Cullen et al., 1997), the intervention in the current study did not attempt to make the foods served more palatable. This may be why there were no changes in students F&V preferences. Across both groups, children reported higher preferences for fruits and lower preferences for vegetables. Despite their strong fruit preferences, students still did not eat the majority of fruit served. It is unclear if modifying the foods served or making changes in the school environment would have helped improve F&V consumption over time.

Baseline BMI-for-age z-scores indicated that children in both groups were almost one standard deviation above average. It was hypothesized that BMI-for-age may decrease at the group level as a function of participating in the intervention. However, this hypothesis was not supported. This is not surprising, given the exclusive focus on F&V consumption. Obesity is the result of complex, multi-faceted factors (Klein et al., 2008) and its prevention requires a more comprehensive approach than that employed in this study (e.g., The HEALTY Study Group, 2010). Although F&V consumption is one important component of a healthy diet, many eating (and physical activity) behaviors need to be targeted to decrease BMI.

Limitations

Limitations included the number of schools that participated in the study due to significant costs per school enrolled which impacts generalizeability and may lead to biased estimates due to inability to account for clustering of students within schools; a moderate consent rate; and the attrition rate over the years. Study strengths include the longitudinal design with annual assessment points, the use of an objective, precise means of measuring F&V intake, a delayed follow-up period and the inner-city study setting with a racially and ethnically diverse group of participants.

Conclusion

Many studies have documented the short-term effects of school-based F&V promotion interventions. This study examined intervention effects on eating behaviors over a 3.5 year period and found positive changes in knowledge throughout the study and on consumption in the early years. Although initial findings were encouraging and consistent with prior literature, persistent declines were observed in the experimental group over time. This finding has implications for the design of school-based F&V promotion interventions, including the need to address the now documented decline in consumption as study years go on.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [K23HD047480]. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jessica A. Hoffman, Northeastern University

Douglas R. Thompson, Thompson Research Consulting

Debra L. Franko, Northeastern University

Thomas J. Power, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Stephen S. Leff, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Virginia A. Stallings, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

References

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Davis M, Resnicow K, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Lin LS, Smith M, Wang DT. Gimme 5 Fruit, Juice, and Vegetables for fun and health: Outcome evaluation. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:96–111. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beunckens C, Molenberghs G, Kenward MG. Direct likelihood analysis versus simple forms of imputation for missing data in randomized clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2005;2:379–386. doi: 10.1191/1740774505cn119oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of Eating Behaviors Among Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101S:539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Marlin DW. I don’t like it; I never tried it: Effects of exposure on two-year-old children’s food preferences. Appetite. 1982;3:353–360. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(82)80053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hoffman J. School-based promotion of fruit and vegetable consumption in multi-culturally diverse, urban schools. Psychol Sch. 2008;45:16–27. doi: 10.1002/pits.20275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hoffman J, Leff SS, Franko DL, Weinstein E, Beakley K, Power TJ. Using a multi-component, partnership-based approach to improve participation rates in school-based research. School Ment Health. 2009;1:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s12310-008-9000-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hoffman J, Kelleher C, Power TJ, Leff SS. Promoting healthy food consumption among young children: Evaluation of a multi-component nutrition education program. J Sch Psychol. 2004;42:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hoffman J, Wilcox KA, Dunn L, Leff SS, Power TJ. Family involvement in school-based health promotion: Bringing nutrition information home. School Psych Rev. 2008;37:567–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H, Prescott R. Applied mixed models in medicine. Wiley; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cole K, Waldrop J, Auria D, Garner JH. An integrative research review: Effective school-based childhood overweight interventions. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2006;3:166–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2006.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AG, Arner TG, Sunki GG, Friedman R, Lantinga M, Sangam S, Zubieta JC, Sullivan KM, Brendel KA, Gao Z, Fontaine N, Shu M, Fuller G, Smith DC, Nitschke DA, Fagan RF. Epi Info™, a database and statistics program for public health professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois S. Accuracy of visual estimates of plate waste in the determination of food consumption. J Am Diet Assoc. 1990;90:382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge AL, Smith-Warner SA, Lytle LA, Murray DM. Comparison of 3 methods for counting fruits and vegetables for fourth-grade students in the Minnesota 5 a day power plus program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:777–782. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Cheung LWY, Peterson KE, Ghomitz G, Cradle JH, Dart H, et al. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999a;153:975–983. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, Laird L. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999b;153:409–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JA, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Stallings VA, Power TJ. Longitudinal behavioral effects of a school-based fruit and vegetable promotion program. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:61–71. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howerton MW, Bell BS, Dodd KW, Berrigan D, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Nebeling L. School-based nutrition programs produced a moderate increase in fruit and vegetable consumption: Meta and pooling analyses from 7 studies. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39:186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein EG, Lytle LA, Chen V. Social Ecological Predictors of the Transition to Overweight in Youth: Results from the Eating for Energy and Nutrition at Schools (TEENS) Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirks BA, Wolff HK. A comparison of methods for plate waste determinations. J Am Diet Assoc. 1985;85:328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knai C, Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M. Getting children to eat more fruit and vegetables: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2006;42:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman TG, Roche AR, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Human Kinetics; Champaign, IL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA, Murray DM, Perry CL, Story M, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY, Varnell S. School-based approaches to affect adolescents diets: Results from the TEENS study. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:270–287. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas TA, Johnson CC. Outcomes of a high school program to increase fruit and vegetable consumption: Gimme 5- a fresh nutrition concept for students. J Sch Health. 1998;68:248–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Kuzmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CL, Bishop DB, Taylor GL, Davis M, Story M, Gray C, et al. A randomized school trial of environmental strategies to encourage fruit and vegetable consumption among children. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:65–76. doi: 10.1177/1090198103255530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay TB, Ashbury FD, Roberts M, Rootman I. Effective components for nutrition interventions: A review and application of the literature. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:418–427. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The HEALTY Study Group. A school-based intervention for diabetes risk reduction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]