Summary

Understanding molecular immunity against mycobacterial infection is critical for the development of effective strategies to control tuberculosis (TB), which is a major health issue in the developing world. Host immunogenetic studies represent an indispensable approach to understand the molecular mechanisms against mycobacterial infection. A superb paradigm is the identification of rare mutations causing Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases (MSMD). Mutations in the interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) receptor genes are highly specific (although not exclusive) for mycobacterial infection. Only dominant negative mutations of STAT1 have specific susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. Mutations in the interleukin-12 (IL-12) signaling genes have phenotypes with non-specificity. Current studies highlight a complex molecular network in antimycobacterial immunity, centered on IFN-γ signaling.

Keywords: Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases, Interleukin-12, Interferon-gamma, IKBKG

Mycobacterial infection and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by the transmission of TB bacilli in aerosols. Before the advent of effective chemotherapy in the mid-twentieth century, more than half of patients with TB died within 5 years. The most common disease-causing species of TB bacilli is Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than two billion people in the world (one third of the world’s population) were infected by MTB in 2009, and about one in 10 will develop disease (http://www.who.int/tb/en/).

MTB infection initiates from the inhalation of aerosolized infectious droplets into the alveoli of the lungs. On entering the alveoli, MTB are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. The innate immune system of the host and the virulence of MTB are two key components that determine the outcome of the MTB infection. The alveolar macrophage with its phagosomes is both the site of elimination of MTB and the site of TB bacillus replication. Depending on host and bacterial factors, either the MTB will multiply and destroy the infected macrophages, and infect more macrophages, or be eliminated by the macrophage phagosomes. Subsequently, infected macrophages migrate to the draining lymph nodes, present MTB antigens to naïve CD4+ T-lymphocytes, and activate Th1 cellular immunity.

Dendritic cells play a critical role in priming the Th1 response.1 The activation of adaptive immunity takes 2–4 weeks. The Th1 response activates macrophages and the delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction, which is a double-edged sword with the beneficial effect of eliminating MTB and the harmful effect of tissue damage.2 Activated macrophages and lymphocytes accumulate at the site of infection and form granulomas. Caseous necrosis can be seen at the center of the granuloma, and occurs as a result of tissue damage caused by the DTH reaction. If MTB disseminate before the activation of adaptive cellular immunity, or the local infection cannot be contained by the cellular immune responses, symptomatic primary TB will develop.

Adaptive cellular immunity against MTB infection is critical to prevent primary TB. By inducing adaptive cellular immunity, bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG, named after the two pioneers who developed the virulence-reduced live vaccine of Mycobacterium bovis) vaccination has been successfully used in the prevention of primary TB in children.3–6 However, BCG is not helpful to clear MTB. MTB can remain dormant in granulomas for decades. During the lifetime of the host, a number of situations may impair the host immunity systemically (e.g., AIDS, diabetes, aging, etc.) or locally (e.g., silicosis or smoking), and cause the reactivation of MTB and the development of active TB. Knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying this complex process is critical for the development of effective prevention and treatment measures.

Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases (MSMD)

Familial atypical mycobacteriosis (FAM, MIM 209950) is a rare congenital condition characterized by familial inherited immunodeficiency to mycobacterial infection, which is more popularly known as Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases (MSMD). Mutations causing MSMD have been identified in several genes. Because of the lethal effects of the MSMD mutations, the frequencies of these mutations are extremely rare (<1/million).7 The identification of these MSMD mutations not only enables precise diagnosis and guided treatment for MSMD, but also highlights the central molecular mechanisms of host immunity to mycobacterial infection, which is a superb paradigm for clarifying the molecular immune mechanisms of a disease by the genetics approach.

MSMD has simple Mendelian inheritance patterns, i.e., autosome dominant, autosome recessive, or X-linked inheritance. Clinically, MSMD is characterized by serious disseminated infection in early childhood of low virulence mycobacteria, most commonly BCG vaccine. The patients are resistant to infection with most other bacteria, fungi, and parasites. The Mendelian inheritance suggests the disease is controlled by a single mutation. Both patterns of autosome inheritance and X-linked inheritance suggest that a mutation causing MSMD can be from either an autosome gene or an X-chromosome gene. This selective susceptibility to mycobacterial infection demonstrates the critical roles of mutated genes in immunity against mycobacteria.

The BCG vaccine is comprised of virulence-attenuated M. bovis sub-strains, and was first developed by Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin at the beginning of the twentieth century by culturing virulent M. bovis on bile-containing medium for 230 serial passages. The attenuation of virulence results from the mutations involving M. bovis proteins mediating its virulence, including ESX-1, PDIM/PGL, and PhoP.8 Live BCG bacilli induce the adaptive cellular immune responses by the cross-reactive antigens of MTB bacilli. The immunogenicity of BCG is mediated by M. bovis proteins different from those mediating its virulence. BCG vaccination is a highly cost-effective intervention against severe childhood TB, and is significantly associated with a reduction in the incidence of pulmonary TB and extrapulmonary disease in early childhood, such as meningitis and miliary TB.3–6 The BCG vaccination is not efficacious in the prevention of pulmonary TB in adolescents and adults, as it does not prevent the establishment of primary infection or reactivation of latent MTB.5,9,10 The administration of BCG vaccination in neonates is relatively safe. However, in individuals with MSMD mutations, disseminated infection and bacteremia may develop.

Seven genes have been identified with MSMD mutations. Six of the seven genes are involved in the signaling of two cytokines, i.e., interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-12 (IL-12). The other gene, IKBKG, participates in the regulation of IL-12 and IFN-γ signaling, and other immune processes by the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway. The major components involved in the signaling of these two cytokines are listed in Table 1. Among these signaling components, the three Janus tyrosine kinases, JAK-1, JAK-2, and TYK-2, are involved in the signaling of a number of cytokines besides IFN-γ and IL-12. STAT1 mediates the signaling of both IFN-γ and IFN-α/β, and STAT4 mediates the signaling of both IL-12 and interleukin-23 (IL-23).

Table 1.

Genes involved in interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-12 (IL-12) signaling

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Chromosome position | Nucleotide position (NCBI Build 37.2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Genes involved in IFN-γ signaling | |||

| IFNG | Interferon-gamma | 12q14 | Chr12: 68548550..68553521 |

| IFNGR1a | Interferon-gamma receptor-1 | 6q23–q24 | Chr6: 137518621..137540567 |

| IFNGR2a | Interferon-gamma receptor-2 | 21q22 | Chr21: 34775202..34809828 |

| JAK1 | Janus kinase 1 | 1p32.3–p31.3 | Chr1: 65298906..65432187 |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 | 9p24 | Chr9: 4985245..5128183 |

| STAT1a | Signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 | 2q32 | Chr2: 191833762..191878976 |

| 2. Genes involved in IL-12 signaling | |||

| IL12A | Interleukin 12 subunit p35 | 3q25.33–q26 | Chr3: 159706629..159713806 |

| IL12Ba | Interleukin-12 subunit p40 | 5q31.1–q33.1 | Chr5: 158741791..158757481 |

| IL12RB1a | Interleukin-12 receptor beta-1 chain | 19p13 | Chr19: 18170371..18197697 |

| IL12RB2 | Interleukin 12 receptor, beta 2 chain | 1p31.3–p31.2 | Chr1: 67773047..67862583 |

| TYK2a | Tyrosine kinase 2 | 19p13.2 | Chr19: 10461204..10491248 |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 | 9p24 | Chr9: 4985245..5128183 |

| STAT4 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 | 2q32.2–q32.3 | Chr2: 191894306..192015925 |

| 3. Other | |||

| IKBKGa | Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma |

Xq28 | ChrX: 153770459..153793261 |

Genes with MSMD (MIM 209950) mutations.

Functional impact of the MSMD mutations

Mutations leading to MSMD are listed in the Supplementary Information (Table S1). The mutations have different impacts on gene structure and function.

Deletion/insertion

Based on DNA structure changes, three types of deletion/insertion (del/ins) mutations can be seen, i.e. deletion, insertion, and combined deletion/insertion. In the combined deletion/insertion, e.g., c. 1440_1447delins16 in the IL-12 receptor beta-1 chain gene ( IL12RB1),11 a DNA fragment from the 1440th to 1447th nucleotide in the IL12RB1 coding sequence is deleted, and a different fragment of 16 nucleotides is inserted in the same position.

The del/ins mutations have different impacts on the protein sequence. An in-frame del/ins mutation does not change the protein sequence downstream of the mutation site. For example, the c.295_306del in the interferon-gamma receptor-1 gene (IFNGR1, encoding IFNγR1)12 is a deletion of 12 nucleotides, or four amino acid codons. In contrast, if the deleted or inserted nucleotides are not in triplets, the protein open reading frame will be shifted from the mutation site. A frame-shift del/ins often causes a premature termination codon downstream, e.g., c.22delC in the IFNGR1 gene,13,14 which causes a frame-shift from the 8th codon, and produces a premature stop codon at six amino acids downstream. A premature termination codon may have two functional effects, i.e., the production of a truncated protein or accelerated messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation by nonsense-mediated decay (NMD). NMD is a protective mRNA surveillance mechanism to prevent the expression of truncated or erroneous protein by inducing the degradation of abnormal mRNA.15 An abnormal mRNA that activates the NMD pathway by the presence of a premature termination codon is degraded. Neither the mRNA translation initiation complex is formed, nor is the mRNA available for translation.

Splice site mutation

In the nascent mRNA precursors synthesized by gene transcription, intronic regions need to be removed from heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) to produce functional mRNA. hnRNA splicing, integrated in the unified gene expression process,16 is mediated by the spliceosomes. The 5′ splice site (splice-donor site) and the 3′ splice site (splice-acceptor site) of an intronic region have highly conserved consensus sequences, i.e., GT at the 5′ end and AG at the 3′ end. Mutations at the canonical splice sites cause the failure of intron splicing, and consequent exon skipping. Exon skipping may produce a premature termination codon, which can induce NMD. For example, the splice-donor site mutation c.200+1G>A at intron 2 of the IFNGR1 gene17,18 has the highly conserved GT dinucleotide replaced by AT, which abolishes the 5′ splice site and causes exon 2 skipping. The exon 2 skipping produces a stop codon immediately downstream.

Missense mutation

Missense mutations usually refer to single nucleotide mutations that cause an amino acid change. Compared to frame-shift or splice site mutations, missense mutations tend to have less impact on gene function. However, a single amino acid change in a conserved protein functional domain or at a critical functional site may have a dramatic impact on gene function. For example, an intra-chain disulfide bridge between Cys77 and Cys85 in the IFN-γ receptor α (IFNγR1, or IFNγRα) is essential for binding with IFN-γ.19 The missense mutations, c.230G>A (Cys77Tyr) and c.254G>A (Cys85Tyr), abolish the disulfide bridge and cause complete deficiency of IFNγR1 activity.12,20

Theoretically, the functional effect of a missense mutation can be predicted based on the sequence conservation across different species and the distance of the properties of two amino acids. A highly conserved region across different species, which can be located by multiple sequence alignments of orthologs, suggests its functional importance. The distance of two amino acids can be assessed by their physiochemical properties21 or evolutionary properties.22 Computer programs, e.g., SIFT23 and PolyPhen,24 can assist in the prediction of the functional effect of a missense mutation. SIFT makes the prediction based on sequence homology and physical properties of amino acids (http://sift.jcvi.org). PolyPhen predicts the function by protein structure analysis (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/). The combined usage of different algorithms can improve the prediction.

Nonsense mutations and start codon mutations

A nonsense mutation refers to the single nucleotide mutation that replaces an amino acid codon with a premature stop codon, which may produce a truncated protein (e.g., c.832G>T in the IFNGR1 gene25) or induce NMD (e.g., c.347C>A in the IFNGR1 gene26,27).

The mutation c.2T>A in IFNGR1 is in the start AUG codon. This mutation destroys the proper translation initiation site. For gene translation, an alternative and less efficient translation initiation site has to be used. A translation initiation site has the highly conserved consensus sequence, RCCAUGG, known as the Kozak sequence.28 The A nucleotide of the AUG start codon is referred to as position 1, and the preceding C nucleotide is referred to as position −1. R at position −3 (R−3) represents A or G. The AUG is essential. The G at position +4 (G+4) and R−3 are highly conserved. The replacement of G+4 or R−3 with another nucleotide has a dramatic impact on translation efficiency.29,30 During the initiation of translation, eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) bind to the mRNA poly-A tail and m7G cap, and recruit the ribosome 40S subunit carrying the eIF2 and methionyl transfer RNA (Met-tRNAi). The pre-initiation complex scans the mRNA to find the first proper Kozak sequence. The original translation initiation site on the IFNGR1 mRNA (NM_000416.2: 101–107) has the highly efficient Kozak sequence, AGCAUGG. The c.2T>A mutation abolishes the original initiation site, and causes the ribosome 40S subunit to continue the scanning of the mRNA to find an alternative initiation site. The next AUG codon on the IFNGR1 mRNA, GUCAUGC (NM_000416.2:131–137), does not have the conserved G+4. The third AUG codon, GAGAUGG (NM_000416.2: 155–161), is a proper Kozak sequence. The study by Wang and Rothnagel31 showed that A−3 has higher translational efficiency than G−3 in a Kozak sequence. Therefore, this alternative translation initiation site is predicted to be less efficient than the destroyed original one. Empirically, Kong et al. showed lower protein expression by the alternative initiation site, while the additional cryptic translation initiation site remained to be identified.32 Because of the remnant expression of IFNγR1, the patient with a homozygous c.2T>A mutation has the phenotype of partial IFNγR1 deficiency.

IFN-γ signaling in MSMD

IFN-γ signaling

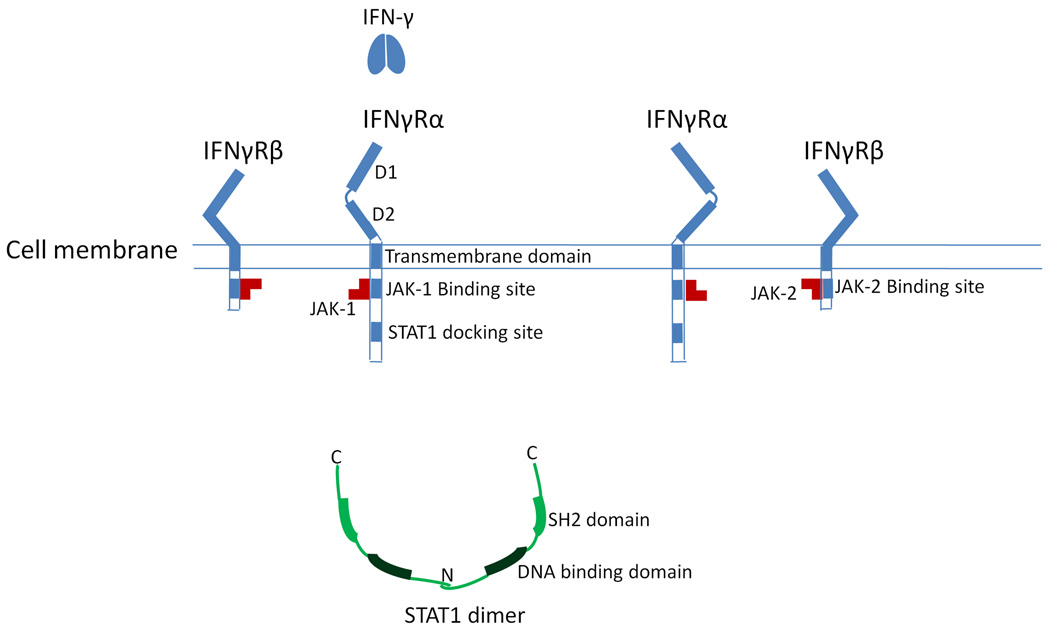

MSMD mutations have been identified in three genes involved in IFN-γ signaling, i.e., IFNGR1, the interferon-gamma receptor-2 gene (IFNGR2, encoding IFNγR2 or IFNγRβ), and the signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 gene (STAT1, encoding STAT1) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The proteins involved in interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) signaling. Without the binding of IFN-γ, the IFN-γ receptor subunits are not associated with each other. IFNγR1 binds with JAK-1, and IFNγR2 binds with JAK-2. STAT1 exists in the cytoplasm as a homodimer through the interaction of N-terminal domains.

The IFN-γ receptor on the cell surface is a complex comprised of two different proteins, IFNγR1 and IFNγR2. From the N-terminal, each protein has an extracellular region, a transmembrane region, and an intracellular region. Without the binding of IFN-γ, the monomers of IFNγR1 and IFNγR2 do not associate with each other. In the extracellular region of IFNγR1, there are two functional domains, D1 and D2. These two domains bind the IFN-γ ligand, and the interaction with the extracellular region of IFNγR2.33 In the intracellular region of IFNγR1, the important functional domains include a Janus kinase 1 (JAK-1) binding site and a STAT1 docking site when phosphorylated.34 JAK-1 binds with IFNγR1 constitutively. The extracellular domain of IFNγR2 has the function of stabilizing the structure and function of the IFNγR1 extracellular domain. The intracellular region of IFNγR2 contains a Janus kinase 2 (JAK-2) binding site, which associates with JAK-2 constitutively.35 The tyrosine kinase activities of JAK-1 and JAK-2 are interdependent. Inactivated STAT1 exists in the cytoplasm as a homodimer through the interaction of its N-terminal domain.36,37

With the binding of the homodimeric IFN-γ, two IFNγR1 subunits form a homodimer. Consequently, two IFNγR2 subunits are recruited to the IFNγR1 dimer. The binding of IFNγR2 to IFNγR1 brings the two Janus tyrosine kinases into physical proximity and initiates the tyrosine kinase activity, which phosphorylates and activates the STAT1 docking site on IFNγR1. The STAT1 SH2 domain binds to the docking site on IFNγR1, which enables the Janus kinases to phosphorylate the Tyr701 at the C-terminal tail segment of STAT1. Then, the phosphorylated STAT1 dissociates from the IFN-γ receptor complex. The SH2 domain of each STAT1 binds with the phosphorylated tail segment of the other STAT1, and forms the active STAT1 homodimer.38 The active STAT1 homodimer will translocate to the nucleus and regulate the transcription of IFN-γ induced genes. This process of IFN-γ signaling is shown in the Supplementary Information (Figure S1: IFN-γ signaling).

MSMD mutations in the IFN-γ signaling genes

People with MSMD mutations in each of the IFN-γ signaling genes have either complete or partial deficiency of the encoded protein. The inheritance model of the disease can be either autosome-recessive or autosome-dominant. Autosome-dominant inherited MSMD patients with mutations of the IFN-γ signaling genes always have partial gene deficiency. The partial gene deficiency is from the dominant negative effect by the expression of aberrant proteins. The aberrant proteins caused by the dominant-negative mutations cannot mediate IFN-γ signaling. Instead, the aberrant proteins interrupt the function of the wild-type protein, either by competition for the ligands or by effective inactivation of the wild-type protein through the formation of nonfunctional dimer. For example, the dominant-negative mutations from the IFNGR1 gene express stable truncated proteins.25,39–44 These truncated proteins have correct sequences for the extracellular and transmembrane domains, thus have the capability to compete for IFN-γ and dimerize with wild-type IFNγR1. Without the interruption by the aberrant proteins, the expression of a single wild-type allele is sufficient for gene function. This point is clearly demonstrated by the fact that heterozygous carriers of the mutations abolishing gene expression are healthy.

Complete deficiency of IFNγR1 or IFNγR2 has a much worse prognosis than partial deficiency.40 However, the immunodeficiency caused by the MSMD mutations from these two genes is specific for susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. This specificity highlights the critical function of IFN-γ signaling for immunity to mycobacteria.

Mutations of STAT1 downstream of the IFN-γ signaling

STAT1 participates in both the IFN-γ signaling of mycobacterial immunity and the IFN-α/β signaling of viral immunity, by different modes. In IFN-γ signaling, STAT1 acts as a homodimer. In contrast, in IFN-α/β signaling, STAT1 acts with STAT2 and interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) as the heterotrimeric transcription factor, interferon-stimulated transcription factor 3 (ISGF3).45 The mutations causing STAT1 deficiency have three different phenotypes, i.e. recessive-inherited complete deficiency,46–48 recessive-inherited partial deficiency,49 and dominant-inherited partial deficiency.47,50 IFN-γ production in response to BCG and IL-12 stimulation is normal in partial STAT1 deficiency,47 but impaired in complete STAT1 deficiency.46

Three mutations have been reported to cause recessive-inherited complete deficiency. Two mutations, c. 1760_1761del and c. 1927insA, are frame-shift deletion/insertions. The c.1760_1761del causes a frame-shift from the 587th codon and produces a premature stop codon 17 amino acids downstream.48 The c. 1927insA causes a frame-shift from the 643rd codon, and produces a premature stop codon three amino acids downstream.46,47 Both mutations, truncating the SH2 tail and transactivation domains of STAT1, abolish the protein expression by inducing NMD. Another mutation c. 1799T>C (Leu600Pro) is a missense mutation that causes a critical amino acid change in the SH2 domain.48 The SH2 domain is essential to form the active STAT1 homodimer by binding with the phosphorylated tail of the other STAT1. The missense Leu→Pro mutation at codon 600 abolishes the dimerization function of the SH2 domain, thus causing complete STAT1 deficiency in individuals with homozygous mutations. It is noteworthy that the mutated allele Pro600 has stable protein expression and that heterozygous individuals with this mutation are healthy without a dominant negative phenotype. Therefore, the SH2-mediated dimerization of STAT1 is the key to the dominant negative effect of MSMD mutations.

The mutation c.2086C>T causes recessive-inherited partial deficiency of STAT1. The c.2086C>T is a missense Pro→Ser mutation at the 696th codon. The functional effect of this mutation is from the regulation of gene expression rather than from the change of amino acid or protein structure. This mutation impairs, but does not abolish, STAT1 mRNA splicing, probably by disrupting an exonic splice enhancer.49

Three MSMD mutations in STAT1 have autosome-dominant inheritance, and all are missense mutations causing a single amino acid change with dominant negative effect. The mutations, c.958G>C and c. 1389G>T, cause nonconservative amino acid changes in the DNA binding domain.47 Another mutation c.2117T>C causes a nonconservative amino acid change at the STAT1 tail domain that interferes in the phosphorylation of Tyr701.50 The aberrant proteins expressed by these mutations have an intact SH2 domain that is able to dimerize with phosphorylated wild-type STAT1, and they therefore manifest a dominant negative effect by consuming wild-type STAT1 and forming nonfunctional dimer when activated by IFN-γ.

The diverse phenotypes of the STAT1 mutations provide further evidence for the central role of IFN-γ signaling in mycobacterial immunity. The recessive-inherited STAT1 deficiency, either partial or complete, results in susceptibility to both mycobacterial and viral infection, including herpes simplex virus-1 and Epstein–Barr virus. This fact can be explained by the impaired signaling of both IFN-γ and IFN-α/β in individuals with homozygous mutations. In contrast, the phenotype of dominant-inherited partial deficiency has selective susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. This selectivity points to the specific dominant-negative mechanism in IFN-γ signaling. In the IFN-γ signaling pathway, the expression of aberrant proteins by the mutated allele consumes the wild-type STAT1 by forming nonfunctional dimer. However, in IFN-α/β signaling, the wild-type STAT1 can form active ISGF3 that is unaffected by the mutated protein.

IL-12 signaling in MSMD

IL-12 signaling

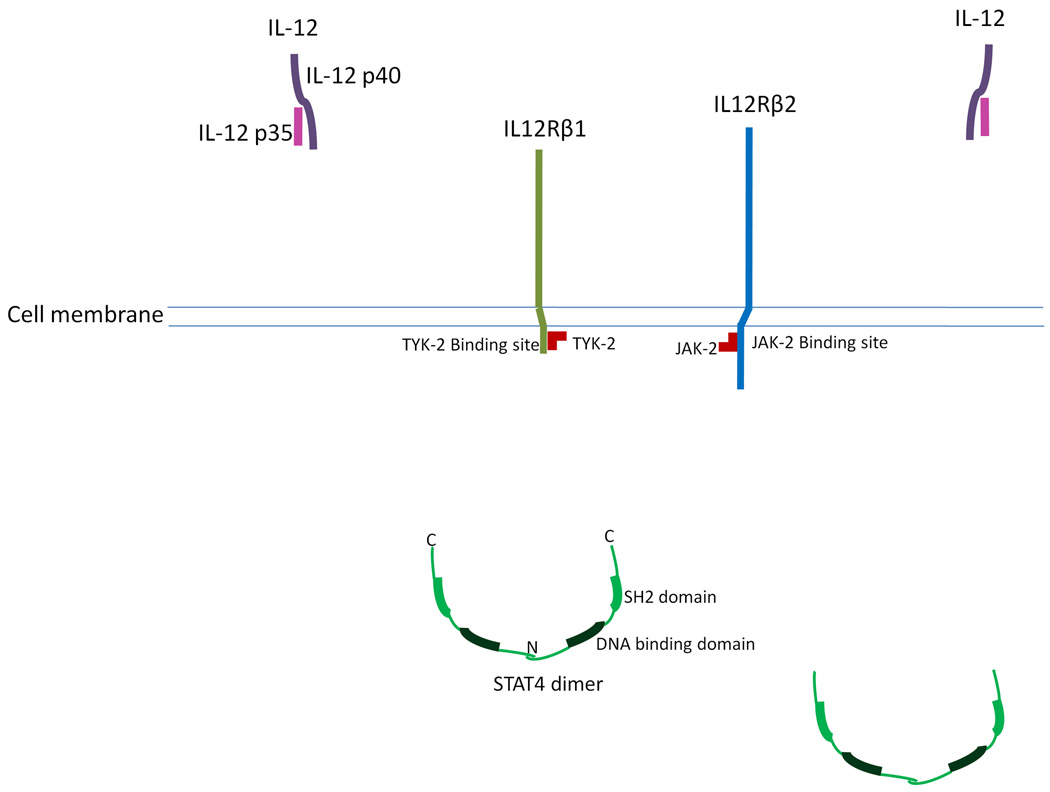

Mutations leading to MSMD have been identified in two genes involved in IL-12 signaling, i.e., the IL-12 subunit p40 gene (IL12B) and IL12RB1. The critical components involved in IL-12 signaling are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The critical components involved in interleukin-12 (IL-12) signaling. IL12R.β1 is associated with TYK-2, and IL12Rβ2 is associated with JAK-2. STAT4 exists in the cytoplasm as a homodimer through the interaction of the N-terminal domains. The active form of STAT4 is a tetramer.

Compared to the IFN-γ signaling complex, the IL-12 signaling complex is more heterogeneous.51 The active form of IL-12 is a heterodimer, comprised of a p35 subunit (encoded by the gene IL12A) and a p40 subunit (encoded by the gene IL12B).52 The p35 subunit is homologous to interleukin-6 (IL-6)53 and the p40 subunit is homologous to the extracellular domain of the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R).53 An active IL-12 receptor also requires two heterogeneous components, i.e., the β1 subunit (encoded by IL12RB1) and the β2 subunit (encoded by IL12RB2). Without the presence of IL-12, the IL-12 receptor subunits do not bind to each other. Each receptor subunit is associated with a Janus tyrosine kinase. The β1 subunit is associated with TYK-2 and the β2 subunit is associated with JAK-2.54 Inactivated STAT4 exists in the cytoplasm as a homodimer through the interaction of its N-terminal domain.37

In the presence of IL-12, each IL-12R subunit binds with an active IL-12 heterodimer. The interaction between the two sets of IL-12 and the receptor subunits forms the hexameric IL-12 signaling complex.52 The formation of the IL-12 signaling complex brings the two interdependent Janus kinases into close proximity, and the two kinases transactivate each other. Consequently, the Janus kinases phosphorylate Tyr800 at the cytoplasmic region of the β2 subunit that activates a STAT4 docking site. Upon activation of the STAT4 docking site, the STAT4 SH2 domain binds to the docking site, which enables the Janus kinases to phosphorylate the C-terminal tail segment of STAT4. Then, the phosphorylated STAT4 dissociates from the IL-12 receptor complex. The SH2 domain recognizes the phosphorylated tail segment of the other STAT4 dimer, and forms an active STAT4 tetramer.37 The active STAT4 tetramer will translocate to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of IL-12 induced genes. This process of IL-12 signaling is shown in the Supplementary Information (Figure S2: IL-12 signaling).

MSMD mutations in the IL-12 signaling genes

MSMD caused by IL-12 signaling mutations is autosome-recessively inherited. The majority of these patients have complete deficiency of the corresponding gene, with the only exception being an MSMD case caused by the mutation Cys198Arg.55 IL-12 signaling is important in the activation of natural killer (NK) cells and T-cells, and in inducing Th1 immunity against mycobacterial infection, but it is not a unique pathway. In the presence of IL-12 signaling deficiency, Mycobacterium-infected macrophages can activate NK cells and a Th1 immune response to produce IFN-γ by an alternative pathway mediated by interleukin-18 (IL-18) signaling.56 Therefore, compared to complete IFN-γ signaling deficiency, not all cases with complete IL-12 signaling deficiency have MSMD.11,57 The immunodeficiency caused by the mutations of IL12B and IL12RB1 is less specific for mycobacterial infection than the IFN-γ signaling mutations. For example, Salmonella infection is also common and can be seen in 38% MSMD patients with IL12B mutations57 and 62% patients with IL12RB1 mutations.11 Other infections, such as Nocardia asteroides,57 Leishmania,58 and fungus,59 have also been reported. The combined immune deficiency may explain the poor prognosis of patients with IL-12 signaling mutations.

Mutation of TYK2 downstream of the IL-12 signaling

One mutation of the tyrosine kinase 2 gene (TYK2), encoding TYK-2, has also been reported to result in generalized BCG infection.60 A 4-bp deletion mutation c.209_212delGCTT causes a shift in the protein reading frame from codon 70 and a premature stop codon 20 amino acids downstream. Complete TYK-2 deficiency caused by this mutation interrupts IL-12 signaling downstream of the ligand-receptor interaction and results in susceptibility to generalized BCG infection. However, TYK-2 participates in the signaling of other cytokines as well, e.g., IFN-α/β and interleukin-10 (IL-10). The immunodeficiency caused by TYK-2 deficiency is therefore not specific for mycobacterial infection. The patient is also highly susceptible to other viral and fungal infections, and may suffer from atopic dermatitis with elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE).60

Besides IL-12 signaling, the proteins encoded by IL12B, IL12RB1, and TYK2, are also critical components of the IL-23 signaling pathway and the development of the Th17 response.61,62 Therefore, impaired IL-23 signaling may also be involved in the MSMD caused by these gene mutations and explain the non-specificity of infections. However, no effect of IL-23 on the production of IFN-γ or IL-12 was suggested in a previous study.63 Another study suggested that the role of IL-23 signaling may be less critical than that of IL-12 signaling in immunity against mycobacterial infection.64

MSMD mutations in the IKBKG gene

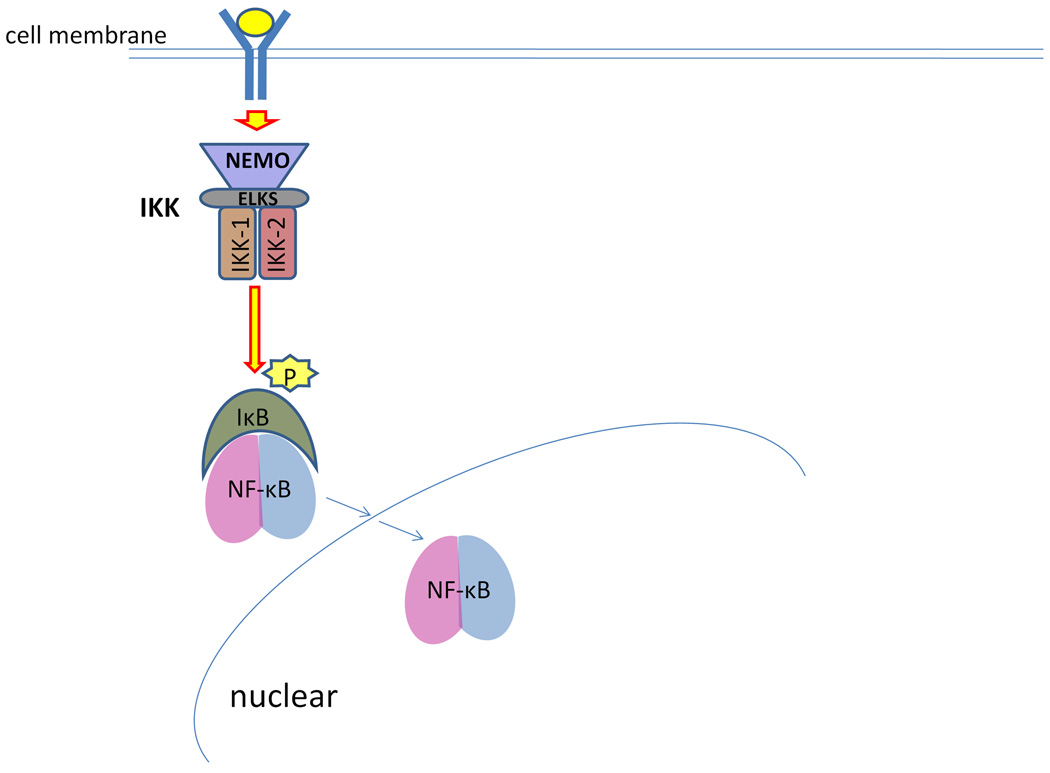

Besides the genes involved in IFN-γ and IL-12 signaling, a mutation in the gene IKBKG (the inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma) at chrXq28 has also been associated with MSMD.65 The protein encoded by IKBKG is also known as NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO), and mediates a critical NF-κB activation pathway. Inactive NF-κB dimer in cytoplasm is bound by the inhibitory proteins, known as the inhibitor of κB (IκB). The activation of NF-κB is mediated by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which phosphorylates IκB and induces the ubiquitination of IκB. The IKK complex is comprised of two catalytic subunits Ikk-1 and Ikk-2, the essential regulatory subunits NEMO and ELKS, and other proteins.66 The role of NEMO is to mediate cell surface signals to activate the IKK complex.67 Ubiquitinated IκB is degraded by the proteosomes in cytoplasm, and active NF-κB dimer is released. Active NF-κB dimer translocates to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of NF-κB target genes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Nuclear factor kappa B essential modulator (NEMO) and NF-κB activation. NEMO is a critical regulatory component of IκB kinase (IKK), which receives cell surface signals and activates the IKK catalytic subunits Ikk-1 and Ikk-2. Activated IKK phosphorylates IκB, and induces the degradation of IκB. Released by the inhibitory IκB, active NF-κB dimer translocates to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of target genes.

NEMO-mediated NF-κB activation regulates the transcription of a number of target genes involved in development and immunity. Mutations causing complete NEMO deficiency cause embryonic death in males and extremely skewed X inactivation and familial incontinentia pigmenti in females.68 Mutations causing partial NEMO deficiency (i.e., hypomorphic mutations) have the phenotype of ectodermal dysplasia and immunodeficiency. The immunodeficiency caused by partial NEMO deficiency involves both innate immunity, by impairing toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling, and adaptive immunity. For the adaptive immune deficiency, both cellular and humoral immunity are impaired.69 Such patients are susceptible to both pyogenic bacteria and mycobacterial infection.70 Selective susceptibility to mycobacterial infection has also been reported, associated with an X-linked recessive MSMD.65 Empirically, the mutations leading to MSMD have been shown to impair the production of IL-12.65 In addition, NEMO mutations may also impair the production of IL-18.71 The combined defect of impairing both IL-12 and IL-18 production can explain the impaired IFN-γ signaling and the specific mycobacterial susceptibility. However, compared with the NEMO mutations causing combined immunodeficiency, the NEMO mutations with selective MSMD phenotype have a less serious impact on NEMO gene function. The selective susceptibility may reflect the necessity of intact innate and adaptive immunity for protection against mycobacterial infection.

Summary

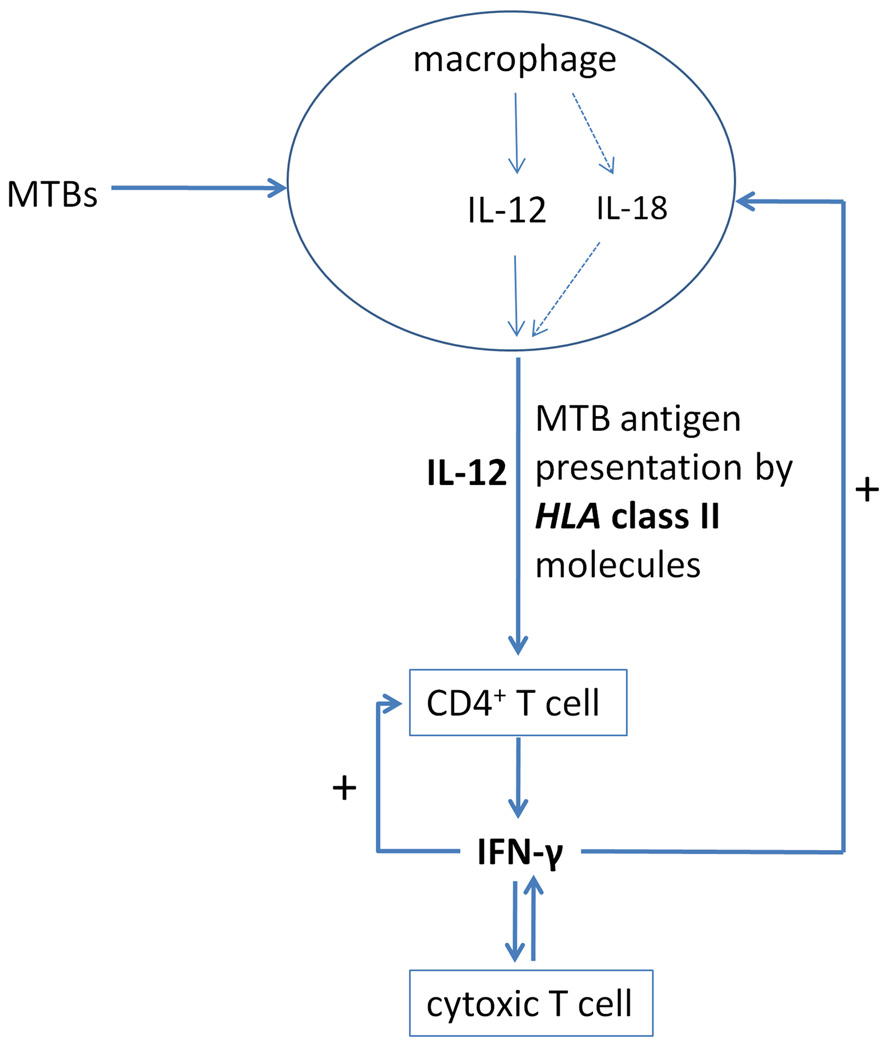

The genetic studies of MSMD demonstrate a complex molecular network involved in the immunity to mycobacterial infection (Figure 4). After phagocytizing MTB, proinflammatory macrophages present mycobacterial antigens to CD4+ T-lymphocytes and secrete IL-12.72 The HLA class II molecules on the surfaces of macrophages present mycobacterial antigens to the T-cell receptors (TCR) on the surfaces of CD4+ T-cells. NEMO-mediated NF-κB activation regulates both IL-12 secretion in macrophages and the TCR signaling in CD4+ T-cells. Partial NEMO deficiency can result in selective susceptibility to mycobacterial infection.

Figure 4.

Molecular mechanisms of immunity to mycobacteria revealed by immunogenetic studies.

IL-12 signaling induces the generation of Th1 cells from antigen-activated naïve CD4+ T-cells. Complete IL-12 signaling deficiency by either IL12B or IL12RB1 mutations, has low penetrance and a better prognosis in MSMD, which suggests that macrophages can induce a Th1 response independent of IL-12. Complete IL-12 signaling deficiency is not specific to mycobacterial infection, and Salmonella infection is common. These facts suggest that IL-12 signaling plays important, but not central, roles in antimycobacterial immunity. Downstream TYK-2 mediates the signaling of IL-12, as well as other cytokines, such as IFN-α/β and IL-10. Complete TYK-2 deficiency results in susceptibility to mycobacterial, viral, and fungal infections, as well as atopic dermatitis with elevated serum IgE.

Activated Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ. IFN-γ signaling provides positive feedback to both macrophages and CD4+ T-cells, which amplifies the Th1 response. Complete IFN-γ signaling deficiency caused by mutations of the IFN-γ receptor genes, IFNGR1 or IFNGR2, is highly specific for mycobacterial infection. Downstream STAT1 mediates the signaling of IFN-γ, as well as IFN-α/β. Complete or partial STAT1 deficiency caused by homozygous mutations results in susceptibility to both mycobacterial and viral infections. Only dominant negative mutations of STAT1 have specific susceptibility to mycobacterial infection, depending on the different functional modes of STAT1 in the signaling of IFN-γ and IFN-α/β. This evidence demonstrates that IFN-γ signaling plays a central role in antimycobacterial immunity.

Concerning the critical roles of IFN-γ in the Th1 response, the genetic findings in the MSMD studies may also shed light on the molecular genetics studies of other infectious diseases where the Th1 response plays a key role. Recent studies have demonstrated that IFNGR1 mutation may cause fungal infections, such as coccidiomycosis and histoplasmosis in humans73, 74 and Cryptococcus infection in mice.75 It has also been suggested that common DNA polymorphisms of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 are associated with susceptibility in malaria,76 hepatitis B,77 hepatitis C,78 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,79 and leishmaniasis.80 The molecular network highlighted by the MSMD studies warrants further study in these infectious diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that no competing interests exist. We appreciate the helpful comments from the peer reviewers. We apologize to all colleagues whose work could not be cited owing to space limitations. SPF and JBM are funded by an NIH grant (CMHD P20MD000170-019001) from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The Funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tian T, Woodworth J, Sköld M, Behar SM. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ cells delays the CD4+ T cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and exacerbates the outcome of infection. J Immunol. 2005;175:3268–3272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Ann Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, Wilson ME, Burdick E, Fineberg HV, et al. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. Meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA. 1994;271:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer TF. Preventing tuberculosis with bacillus Calmette–Guerin vaccine: a meta-analysis of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31 Suppl 3:S64–S67. doi: 10.1086/314072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues LC, Diwan VK, Wheeler JG. Protective effect of BCG against tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:1154–1158. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.6.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2006;367:1173–1180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casanova JL, Blanche S, Emile JF, Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi S, Altare F, et al. Idiopathic disseminated bacillus Calmette–Guerin infection: a French national retrospective study. Pediatrics. 1996;98(4 Pt 1):774–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Tran V, Leung AS, Alexander DC, Zhu B. BCG vaccines: their mechanisms of attenuation and impact on safety and protective efficacy. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:70–78. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.2.7210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The role of BCG vaccine in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. A joint statement by the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1996;45(RR-4):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. BCG vaccine. WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004;79:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fieschi C, Dupuis S, Catherinot E, Feinberg J, Bustamante J, Breiman A, et al. Low penetrance, broad resistance, and favorable outcome of interleukin 12 receptor beta1 deficiency: medical and immunological implications. J Exp Med. 2003;197:527–535. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jouanguy E, Dupuis S, Pallier A, Döffinger R, Fondanèche MC, Fieschi C, et al. In a novel form of IFN-gamma receptor 1 deficiency, cell surface receptors fail to bind IFN-gamma. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1429–1436. doi: 10.1172/JCI9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland SM, Dorman SE, Kwon A, Pitha-Rowe IF, Frucht DM, Gerstberger SM, et al. Abnormal regulation of interferon-gamma, interleukin-12, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1095–1104. doi: 10.1086/515670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vesterhus P, Holland SM, Abrahamsen TG, Bjerknes R. Familial disseminated infection due to atypical mycobacteria with childhood onset. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:822–825. doi: 10.1086/514939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lykke-Andersen J, Shu MD, Steitz JA. Communication of the position of exon- exon junctions to the mRNA surveillance machinery by the protein RNPS1. Science. 2001;293:1836–1839. doi: 10.1126/science.1062786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orphanides G, Reinberg D. A unified theory of gene expression. Cell. 2002;108:439–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierre-Audigier C, Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi S, Altare F, Rauzier J, Vincent V, et al. Fatal disseminated Mycobacterium smegmatis infection in a child with inherited interferon gamma receptor deficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:982–984. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altare F, Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Fondaneche MC, Fizame C, Ribierre F, et al. A causative relationship between mutant IFNgR1 alleles and impaired cellular response to IFNgamma in a compound heterozygous child. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:723–726. doi: 10.1086/301750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuber D, Friedlein A, Fountoulakis M, Lahm HW, Garotta G. Alignment of disulfide bonds of the extracellular domain of the interferon gamma receptor and investigation of their role in biological activity. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2423–2430. doi: 10.1021/bi00060a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noordzij JG, Hartwig NG, Verreck FA, De Bruin-Versteeg S, De Boer T, Van Dissel JT, et al. Two patients with complete defects in interferon gamma receptor- dependent signaling. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:490–496. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlin S, Ghandour G. Comparative statistics for DNA and protein sequences: multiple sequence analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:6186–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonnet GH, Cohen MA, Benner SA. Exhaustive matching of the entire protein sequence database. Science. 1992;256:1443–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1604319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, Lathe W, 3rd, Kondrashov AS, Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:591–597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villella A, Picard C, Jouanguy E, Dupuis S, Popko S, Abughali N, et al. Recurrent Mycobacterium avium osteomyelitis associated with a novel dominant interferon gamma receptor mutation. Pediatrics. 2001;107 doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newport MJ, Huxley CM, Huston S, Hawrylowicz CM, Oostra BA, Williamson R, et al. A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1941–1949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levin M, Newport MJ, D’Souza S, Kalabalikis P, Brown IN, Lenicker HM, et al. Familial disseminated atypical mycobacterial infection in childhood: a human mycobacterial susceptibility gene? Lancet. 1995;345:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozak M. An analysis of vertebrate mRNA sequences: intimations of translational control. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:887–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozak M. Recognition of AUG and alternative initiator codons is augmented by G in position +4 but is not generally affected by the nucleotides in positions +5 and +6. EMBO J. 1997;16:2482–2492. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang XQ, Rothnagel JA. 5′-Untranslated regions with multiple upstream AUG codons can support low-level translation via leaky scanning and reinitiation. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:1382–1391. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong XF, Vogt G, Chapgier A, Lamaze C, Bustamante J, Prando C, et al. A novel form of cell type-specific partial IFN-gammaR1 deficiency caused by a germ line mutation of the IFNGR1 initiation codon. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter MR, Windsor WT, Nagabhushan TL, Lundell DJ, Lunn CA, Zauodny PJ, et al. Crystal structure of a complex between interferon-gamma and its soluble high- affinity receptor. Nature. 1995;376:230–235. doi: 10.1038/376230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bach EA, Aguet M, Schreiber RD. The IFN gamma receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:563–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogt G, Chapgier A, Yang K, Chuzhanova N, Feinberg J, Fieschi C, et al. Gains of glycosylation comprise an unexpectedly large group of pathogenic mutations. Nat Genet. 2005;37:692–700. doi: 10.1038/ng1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Vinkemeier U, Zhao Y, Jeruzalmi D, Darnell JE, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of a tyrosine phosphorylated STAT-1 dimer bound to DNA. Cell. 1998;93:827–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ota N, Brett TJ, Murphy TL, Fremont DH, Murphy KM. N-domain-dependent nonphosphorylated STAT4 dimers required for cytokine-driven activation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:208–215. doi: 10.1038/ni1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krause CD, Lavnikova N, Xie J, Mei E, Mirochnitchenko OV, Jia Y, et al. Preassembly and ligand-induced restructuring of the chains of the IFN-gamma receptor complex: the roles of Jak kinases, Stat1 and the receptor chains. Cell Res. 2006;16:55–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storgaard M, Varming K, Herlin T, Obel N. Novel mutation in the interferon- gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:137–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorman SE, Picard C, Lammas D, Heyne K, van Dissel JT, Baretto R, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet. 2004;364:2113–2121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17552-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Lammas D, Dorman SE, Fondanche MC, Dupuis S, et al. A human IFNGR1 small deletion hotspot associated with dominant susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. Nat Genet. 1999;21:370–378. doi: 10.1038/7701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arend SM, Janssen R, Gosen JJ, Waanders H, de Boer T, Ottenhoff TH, et al. Multifocal osteomyelitis caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with a genetic defect of the interferon-gamma receptor. Neth J Med. 2001;59:140–151. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(01)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waibel KH, Regis DP, Uzel G, Rosenzweig SD, Holland SM. Fever and leg pain in a 42-month-old. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:239–243. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61949-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raszka WV, Trinh TT, Zawadsky PM. Multifocal M. intracellulare osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent child. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1994;33:611–616. doi: 10.1177/000992289403301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehrhardt C, Seyer R, Hrincius ER, Eierhoff T, Wolff T, Ludwig S. Interplay between influenza A virus and the innate immune signaling. Microbes Infect. 12:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapgier A, Wynn RF, Jouanguy E, Filipe-Santos O, Zhang S, Feinberg J, et al. Human complete Stat-1 deficiency is associated with defective type I and II IFN responses in vitro but immunity to some low virulence viruses in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;176:5078–5083. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chapgier A, Boisson-Dupuis S, Jouanguy E, Vogt G, Feinberg J, Prochnicka- Chalufour A, et al. Novel STAT1 alleles in otherwise healthy patients with mycobacterial disease. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dupuis S, Jouanguy E, Al-Hajjar S, Fieschi C, Al-Mohsen IZ, Al-Jumaah S, et al. Impaired response to interferon-alpha/beta and lethal viral disease in human STAT1 deficiency. Nat Genet. 2003;33:388–391. doi: 10.1038/ng1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chapgier A, Kong XF, Boisson-Dupuis S, Jouanguy E, Averbuch D, Feinberg J, et al. A partial form of recessive STAT1 deficiency in humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1502–1514. doi: 10.1172/JCI37083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dupuis S, Dargemont C, Fieschi C, Thomassin N, Rosenzweig S, Harris J, et al. Impairment of mycobacterial but not viral immunity by a germline human STAT1 mutation. Science. 2001;293:300–303. doi: 10.1126/science.1061154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gately MK, Renzetti LM, Magram J, Stern AS, Adorini L, Gubler U, et al. The interleukin-12/interleukin-12-receptor system: role in normal and pathologic immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:495–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoon C, Johnston SC, Tang J, Stahl M, Tobin JF, Somers WS. Charged residues dominate a unique interlocking topography in the heterodimeric cytokine interleukin- 12. EMBO J. 2000;19:3530–3541. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merberg DM, Wolf SF, Clark SC. Sequence similarity between NKSF and the IL- 6/G-CSF family. Immunol Today. 1992;13:77–78. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zou J, Presky DH, Wu CY, Gubler U. Differential associations between the cytoplasmic regions of the interleukin-12 receptor subunits beta1 and beta2 and JAK kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6073–6077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.6073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lichtenauer-Kaligis EG, de Boer T, Verreck FA, van Voorden S, Hoeve MA, van de Vosse E, et al. Severe Mycobacterium bovis BCG infections in a large series of novel IL-12 receptor beta1 deficient patients and evidence for the existence of partial IL-12 receptor beta1 deficiency. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:59–69. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Obregon C, Dreher D, Kok M, Cochand L, Kiama GS, Nicod LP. Human alveolar macrophages infected by virulent bacteria expressing SipB are a major source of active interleukin-18. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4382–4388. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4382-4388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Picard C, Fieschi C, Altare F, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Hajjar S, Feinberg J, et al. Inherited interleukin-12 deficiency: IL12B genotype and clinical phenotype of 13 patients from six kindreds. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:336–348. doi: 10.1086/338625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanal O, Turkkani G, Gumruk F, Yel L, Secmeer G, Tezcan I, et al. A case of interleukin-12 receptor beta-1 deficiency with recurrent leishmaniasis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:366–368. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000258696.64507.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moraes-Vasconcelos D, Grumach AS, Yamaguti A, Andrade ME, Fieschi C, de Beaucoudrey L, et al. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis disseminated disease in a patient with inherited deficiency in the beta1 subunit of the interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23 receptor. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:e31–e37. doi: 10.1086/432119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Morio T, Watanabe K, Agematsu K, Tsuchiya S, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ottenhoff TH, Verreck FA, Hoeve MA, van de Vosse E. Control of human host immunity to mycobacteria. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005;85:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cruz A, Khader SA, Torrado E, Fraga A, Pearl JE, Pedrosa J, et al. Cutting edge: IFN-gamma regulates the induction and expansion of IL-17-producing CD4 T cells during mycobacterial infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:1416–1420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chackerian AA, Chen SJ, Brodie SJ, Mattson JD, McClanahan TK, Kastelein RA, et al. Neutralization or absence of the interleukin-23 pathway does not compromise immunity to mycobacterial infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6092–6099. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00621-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Filipe-Santos O, Bustamante J, Haverkamp MH, Vinolo E, Ku CL, Puel A, et al. X-linked susceptibility to mycobacteria is caused by mutations in NEMO impairing CD40-dependent IL-12 production. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1745–1759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sigala JL, Bottero V, Young DB, Shevchenko A, Mercurio F, Verma IM. Activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB requires ELKS, an IkappaB kinase regulatory subunit. Science. 2004;304:1963–1967. doi: 10.1126/science.1098387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sebban H, Yamaoka S, Courtois G. Posttranslational modifications of NEMO and its partners in NF-kappaB signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smahi A, Courtois G, Vabres P, Yamaoka S, Heuertz S, Munnich A, et al. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Nature. 2000;405:466–472. doi: 10.1038/35013114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orange JS, Levy O, Geha RS. Human disease resulting from gene mutations that interfere with appropriate nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Immunol Rev. 2005;203:21–37. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orange JS, Jain A, Ballas ZK, Schneider LC, Geha RS, Bonilla FA. The presentation and natural history of immunodeficiency caused by nuclear factor kappaB essential modulator mutation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Döffinger R, Smahi A, Bessia C, Geissmann F, Feinberg J, Durandy A, et al. X- linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency is caused by impaired NF-kappaB signaling. Nat Genet. 2001;27:277–285. doi: 10.1038/85837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verreck FA, de Boer T, Langenberg DM, Hoeve MA, Kramer M, Vaisberg E, et al. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vinh DC, Masannat F, Dzioba RB, Galgiani JN, Holland SM. Refractory disseminated coccidioidomycosis and mycobacteriosis in interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e62–e65. doi: 10.1086/605532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zerbe CS, Holland SM. Disseminated histoplasmosis in persons with interferon- gamma receptor 1 deficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:e38–e41. doi: 10.1086/432120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou Q, Gault RA, Kozel TR, Murphy WJ. Protection from direct cerebral Cryptococcus infection by interferon-gamma-dependent activation of microglial cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:5753–5761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Naka I, Patarapotikul J, Hananantachai H, Tokunaga K, Tsuchiya N, Ohashi J. IFNGR1 polymorphisms in Thai malaria patients. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1406–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou J, Chen DQ, Poon VK, Zeng Y, Ng F, Lu L, et al. A regulatory polymorphism in interferon-gamma receptor 1 promoter is associated with the susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Immunogenetics. 2009;61:423–430. doi: 10.1007/s00251-009-0377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nalpas B, Lavialle-Meziani R, Plancoulaine S, Jouanguy E, Nalpas A, Munteanu M, et al. Interferon gamma receptor 2 gene variants are associated with liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Gut. 2010;59:1120–1126. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Do H, Vasilescu A, Diop G, Hirtzig T, Coulonges C, Labib T, et al. Associations of the IL2Ralpha, IL4Ralpha, IL10Ralpha, and IFN (gamma) R1 cytokine receptor genes with AIDS progression in a French AIDS cohort. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Salih MA, Ibrahim ME, Blackwell JM, Miller EN, Khalil EA, ElHassan AM, et al. IFNG and IFNGR1 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in Sudan. Genes Immun. 2007;8:75–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.