Abstract

The low lumbar spine is deeply located in flexible segments, and has a physiologic lordosis. Therefore, burst fractures of the low lumbar spine are uncommon injuries. The treatment for such injuries may either be conservative or surgical management according to canal compromise and the neurological status. However, there are no general guidelines or consensus for the treatment of low lumbar burst fractures especially in neurologically intact cases with severe canal compromise. We report a patient with a burst fracture of the fourth lumbar vertebra, who was treated surgically but without fusion because of the neurologically intact status in spite of severe canal compromise of more than 85%. It was possible to preserve motion segments by removal of screws at one year later. We also discuss why bone fusion was not necessary with review of the relevant literature.

Keywords: Burst fracture, Low lumbar spine, Fusion

INTRODUCTION

Burst fractures of the low lumbar spine represent a small percentage of all spine injuries. The iliolumbar ligaments and location below the pelvic brim are two main features unique to these fractures compared to those that occur at the thoracolumbar region12). The indication for anterior decompression and bone grafting is severe canal compromise with neurological deficits that can not be decompressed by the many different approaches available1). However, the criteria for choosing surgery or conservative treatment for the management of low lumbar burst fractures still remains controversial especially in neurologically intact patients even with severe canal compromise2,7). We report a case of L4 burst fracture withsevere canal compromise of more than 85%, but without neurological deficits. A short segment fixation without fusion was performed with satisfactory results, without neurological aggravation.

CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old male patient fell from the fourth floor of a building and had severe low back pain when he was admitted to the hospital. The physical examination revealed no motor or sensory deficits in the legs, bilaterally. The deep tendon reflexes were normoreactive. There was no bladder or bowel dysfunction. There was also no neurological abnormality related to the cauda equina. Simple radiographs in the supine position revealed loss of anterior body height and widening of the pedicles of the L4 vertebra. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar region showed an L4 burst fracture with a spinous process fracture and severe canal compromise due to retropulsed bony fragments (Fig. 1). An operation was planned and performed four days after the injuries to ensure adequate recovery. Postural reduction was performed during this period to achieve a satisfactory reduction. The patient was reassessed for the presence of neurological deficits before the operation, and there was no aggravation of the neurological status compared to the initial examination. We performed short segment posterior fixation without bone fusion (Fig. 2). Distraction force was not applied to avoid moving of retropulsed fragments into the canal which could cause iatrogenic cauda equina syndrome. We did not perform decompression because there were no neurological deficits identified. The patient was allowed to ambulate in a brace on postoperative day 4, after removal of the suction drain. The TLSO brace was applied for three months after the operation. We performed removal of the implants 12 months after the initial operation because of the possibility of implant failure. A CT scan at the 1 year follow-up showed improved canal compromise to 40% (Fig. 3). After the removal of the implants, the patient was able to walk by himself without any difficulties. There were no neurological deficits related to cauda equina or radiculopathy during the 24 postoperative months of follow up.

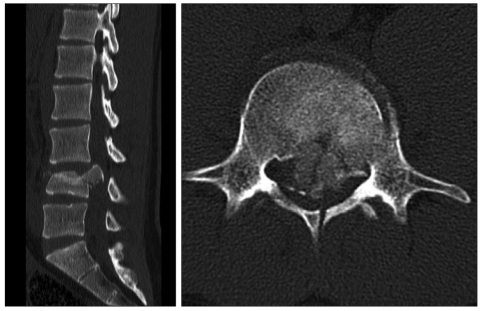

Fig. 1.

A 16-year-old male patient fell down and sustained unstable L4 bursting fracture. Preoperative computed tomography scans demonstrate about 85% canal encroachment and spinous process fracture in spite of neurologically intact status.

Fig. 2.

Postoperative simple radiographs show short segment fixation without fusion by posterior approach.

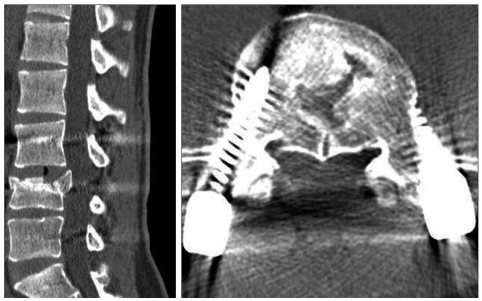

Fig. 3.

Computed tomographic scans at 1 year follow-up reveal bone healing and canal remodelling with improved canal compromise.

DISCUSSION

Burst fractures of low lumbar spine are uncommon injuries of spine. The iliolumbar ligaments and location below the pelvic brim are two stabilizing factors that are unique to these fractures compared with those of thoracolumbar junction. Treatment must be individualized and taken into account the injury pattern, neurological status and anatomical approaches available. Treatments for low lumbar burst fractures are conservative or surgical, either posterior stabilization or by applying an anterior approach9,10). But, there is no strict guideline or consensus regarding the proper approach for such lesion. Kostuik et al.7) suggested that indication for stabilization in the absence of neurologic deficits for burst fracture of thoracolumbar or low region is greater than 50% canal compromise in conjunction with loss of height and local kyphosis because of potential for bone fragment displacement and spinal stenosis by degeneration related to disc and endplate injury. Yazar et al.13) also insisted that anterior decompression and stabilization should be performed for low lumbar burst fractures in case of more than 70% of canal compromise due to risk of future displacement, even though there were no neurologic deficits. However, in the neurologically intact patients, conservative care including initial bed rest with postural reduction, subsequent wearing of brace and ambulation has been an effective treatments for low lumbar burst fractures2,8). Many reports suggested that neurological damage occurs at the moment of injury when the anatomy is most distorted, and there is no correlation between the neurological deficits and the extent of subsequent recovery with spinal canal4,9). The present patient had no neurological deficits, even though he had more than 85% canal compromise. This may be attributed to the position of the conus medullaris, and whether neurological deficit occurs depends on the involvement of the cord, conus medullaris, and cauda equina level. The most common location of conus medullaris is at the lower third of L1. So, in subjects having the spinal cord above the L2 level and cauda equina below it, retropulsed intracanalicular bone fragments at the T11-L1 levels was likely to cause more damage than that of low lumbar spine11). The nerve roots of cauda equina have similarity to the peripheral nerves in capacity for functional recovery. Moreover, the spinal canal is widest in low lumbar region. Finn et al.5) reported no correlation of the degree of neurologic deficits with the amount of canal compromise at time of injury. He also insisted no evidence for the progression of displacement of bone fragments in low lumbar burst fractures and no significant kyphosis with brace treatment. An et al.1) also reported poor results with long level instrumentation and good results achieved with nonoperative treatment. We performed short segment posterior fixation because there was no neurologic deficit, although he had severe canal compromise. With such operation, early ambulation is possible and preserve motion segments by removal of screws compared with long level instrumentation and fusion6). Moreover, the advantages of short segment fixation without fusion in this patient also include immediate pain relief, elimination of donor site pain, reducing blood loss and short operative time. Initially, we were worried about the risk of future displacement which might cause cauda equina syndrome or neural injury. However, he did not require posterior decompression for claudication at the level of injury and canal remodelling was observed at one year follow-up evaluation. Moreover, progressive kyphosis or vertebral collapse did not occur during the follow-up period. Klerk et al.3) reported that the process of remodeling mainly takes place during the first year after injury and after this period, there is little further remodeling. It is for this reason that we removed implants and observed the canal compromise at follow-up 1 year.

CONCLUSION

Even though spinal canal compromise is greater than 85%, it is possible to have no neurological deficit in low lumbar spine. Short segment fixation without bone fusion can be considered as another treatment option for such case owing to its advantages of rapid pain relief, early ambulation, and preserving motion segments.

References

- 1.An HS, Simpson JM, Ebraheim NA, Jackson WT, Moore J, O'Malley NP. Low lumbar burst fractures: comparison between conservative and surgical treatments. Orthopedics. 1992;15:367–373. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19920301-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan DP, Seng NK, Kaan KT. Nonoperative treatment in burst fractures of the lumbar spine (L2-L5) without neurologic deficits. Spine. 1993;18:320–325. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Klerk LW, Fontijne WP, Stijnen T, Braakman R, Tanghe HL, van Linge B. Spontaneous remodeling of the spinal canal after conservative management of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Spine. 1998;23:1057–1060. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199805010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.el Masry WS, Short DJ. Current concept: spinal injuries and rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10:484–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finn CA, Stauffer ES. Burst fractures of the fifth vertebra. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, Park SK, Joy H, Ryu Jk, Kim SW, Ju CI. Bone cement augmentation of short segment fixation for unstable burst fracture in severe osteoporosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;44:8–14. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.44.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kostuik JP. Anterior fixation for burst fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine with or without neurological involvement. Spine. 1988;13:286–293. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198803000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraemer WJ, Schemitsch EH, Lever J, McBroom RJ, McKee MD, Waddell JP. Functional outcome of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficit. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:541–544. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohanty SP, Venkatram N. Does neurological recovery in thoracolumbar and lumbar burst fractures depend on the extent of canal compromise? Spinal Cord. 2002;40:295–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuyama K, Abe E, Chiba M, Ishikawa N, Sato K. Outcome of anterior decompression and stabilization for thoracolumbar unstable burst fractures in the absence of neurologic deficits. Spine. 1996;21:620–625. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saifuddin A, Burnett SJ, White J. The variation of position of the conus medullaris in an adult population. A magnetic resonance imaging study. Spine. 1998;23:1452–1456. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199807010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seybold EA, Sweeney CA, Fredrickson BE, Warhold LG, Bernini PM. Functional outcome of low lumbar burst fractures. A multicenter review of operative and nonoperative treatment of L3-L5. Spine. 1999;24:2154–2161. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199910150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yazar T, Cebesoy O, Soydan C, Köse C. Acute burst fracture of the low lumbar vertebra managed by anterior surgery. Journal of Ankara Medical School. 2004;26:41–45. [Google Scholar]