Abstract

Evolution has long been understood as the driving force for many problems of medical interest. The evolution of drug resistance in HIV and bacterial infections is recognized as one of the most significant emerging problems in medicine. In cancer therapy, the evolution of resistance to chemotherapeutic agents is often the differentiating factor between effective therapy and disease progression or death. Interventions to manage the evolution of resistance have, up to this point, been based on steady-state analysis of mutation and selection models. In this paper, we review the mathematical methods applied to studying evolution of resistance in disease. We present a broad review of several classical applications of mathematical modeling of evolution, and review in depth two recent problems which demonstrate the potential for interventions which exploit the dynamic behavior of resistance evolution models. The first problem addresses the problem of sequential treatment failures in HIV; we present a review of our recent publications addressing this problem. The second problem addresses a novel approach to gene therapy for pancreatic cancer treatment, where selection is used to encourage optimal spread of susceptibility genes through a target tumor, which is then eradicated during a second treatment phase. We review the recent in Vitro laboratory work on this topic, present a new mathematical model to describe the treatment process, and show why model-based approaches will be necessary to successfully implement this novel and promising approach.

Keywords: Evolution, HIV, Combination Chemotherapy, Optimal Control

1. Introduction

The evolution of resistance has long been understood as the root cause of many problems in medicine. High mutation rates, short generation times and large populations make microorganism or viral infections situations in which dramatic evolutionary behavior can be observed in real time [37]. Likewise, in cancer therapy, high levels of genetic instability and high rates of cell turnover insure that resistance will quickly develop to any chemotherapeutic agent [51].

The extent of this problem has lead to significant work in modeling evolutionary dynamics, in order to design treatments that mitigate this risk. Accurate estimates of mutation and turnover rates, together with characterization of resistance mutations, are used to choose the formulation, dosing, and duration of treatment for HIV infection, bacterial infection, and cancer chemotherapy. An excellent primer on the mathematics of various types of evolutionary models can be found in [35]; this book also contains an excellent bibliography on classical applications of evolutionary models.

Evolutionary modeling has also been used to create conditions in which evolution is encouraged. Viral therapies have emerged which target tumor cells [19]. The potency of these treatments is often enhanced by creating an artificial environment in which increased potency results in increased fitness, after which the virus is allowed to evolve freely, resulting in a more potent therapy [33].

These applications of evolutionary modeling are critical to successful treatment of disease. However, these traditional applications of modeling can all be classified as “steady-state” applications; they manipulate conditions such that the likelihood of a desired treatment outcome is maximized, but the treatment options considered are static only. In recent years, a number of new applications of evolutionary modeling, in which dynamic treatment options are considered, have begun to emerge. These treatment options excite the transient dynamics of the mutation-selection equations, resulting in complicated dynamics. The complicated and sometimes counterintuitive treatment schedules which arise from this are excellent applications for modern control methods.

In the broader field of biomedicine, Dr. McAvoy and colleagues published an excellent snapshot review of various ways in which process control concepts are being applied in medicine [6]. In the spirit of that paper, we seek to do the same for emerging applications of dynamic evolutionary models in medicine, particularly those where systems and control theory-based approaches can play a significant role. In this paper, we review in-depth two of these emerging applications, and discuss the applicability of systems, control, and optimization techniques to these problems. One of these is in the area of HIV therapy, and one is in the area of combination chemotherapies for cancer. We also introduce the basic mathematics used to model mutation and selection, and review several classical applications of evolutionary modeling and their impact.

The paper is organized as follows: In Section 2 we briefly introduce the mathematical methods used to create dynamic models of evolution. In Section 3 we review classical applications of evolutionary modeling, including approaches that seek to suppress evolution and approaches that use selection to optimize treatment efficacy. In Section 4, we present a review of recent work [59, 21, 23, 22] showing how a dynamic multi-strain model of HIV infection can be used to create dynamic treatment schedules that reduce the risk of sequential treatment failures. In Section 5 we review a new approach in cancer therapy which relies on dynamic evolutionary processes to increase the effectiveness of a transgene therapy for tumor killing [28, 27]. We present a new mathematical model of the two-step treatment procedure described in the in Vitro studies, and demonstrate how two separate methods of clinical implementation will require the use of model-based strategies. In Section 6 we summarize the recent developments in this field, discuss the ways in which the field will benefit from controls-based approaches, and speculate on similar problems which may arise in the future.

2. Modeling Mutation and Selection

Evolution of resistance is driven by two processes: mutation and selection. In order for resistance to develop, a novel genetic characteristic must occur in the population, and it must persist and expand by providing a replicative advantage. The processes by which the novel genetic characteristics enter the population are broadly termed mutations, and the processes by which these mutant variations persist and grow are termed selection. In this section we introduce the mathematical methods commonly used for modeling these two processes.

2.1. Mutation

Mutations may occur in many different ways, and the dominant mutation mechanism will depend on the application. In HIV therapy, for instance, point substitutions, in which a single RNA nucleotide is randomly substituted for another, is the dominant mechanism by which mutant virus are generated [24], though other mutation events have been known to occur. In bacterial replication, plasmid exchange creates a mechanism by which whole genes can be added to the bacterial genome [49]. In cancer development, dramatic mutations such as whole or partial chromosome deletions tend to dominate [51].

All of these mutation events are binary random processes. Furthermore, they usually occur only during replication events, so they can be treated as discrete random processes. Therefore, if the per-replication likelihood of the mutation event is known, then the number of times that particular mutation is expected to occur during a fixed time-period can easily be computed from the replication rate and population size, and follows a Poisson distribution. If we consider the time history of the parent strain population size p(t), the average lifespan of an individual in that strain Tavg, and a per-replication mutation probability M, then the probability of finding exactly k mutations on the time interval [t0, tf] is

| (1) |

and the probability of finding any mutations would be 1 − Pt ∈ [t0,tf](0|p(t)). It is easy to see how this could be written as a function of tf, and be used to calculate average time to emergence for a mutant strain.

The mutation probability M in this case represents whatever mutational mechanism is most likely to produce the given mutation, which, as mentioned above, depends heavily on the particular application. In the special case where only point substitutions are considered (generally a good assumption for virus populations, as mentioned above), this may be written as M = μD, where μ is the per-replication probability of a single point substitution, and D is the number of point substitutions necessary to generate the mutation in question from the parent population. D is commonly termed the genetic distance, or in viral resistance applications, the genetic barrier height [4].

2.2. Selection

Mutation processes create population diversity, but do not, by themselves constitute evolution. A selection process by which certain mutations are either encouraged or discouraged is also necessary. This takes the form of either competition for a common limited resource or predation by a common predator (or both). The two examples considered in this paper take the form of competition for a common resource.

Selection takes place during the replication and death of the individuals in each subpopulation. These are essentially continuous stochastic processes, so modeling of selection can take the form of ordinary differential equations or stochastic differential equations, depending on how well the large number assumptions are satisfied [35]. Many selective processes can be modeled using ordinary differential equation models similar to:

| (2) |

where x(t) represents the population of shared resources, and y1(t), y2(t) are two mutational variants competing for those resources. The shared resources may be nutrients, or in the case of infectious processes, target hosts. It is easy to see how the equations may be scaled for an arbitrary number of mutational variants.

These simple equations are sufficient to describe three concepts common to evolutionary systems. The first is the concept of basic reproductive ratio, or R0. R0 is defined as the average number of viable offspring produced by each parent during its lifespan, assuming small numbers and abundant resources. In the context of differential equation modeling, it corresponds to the initial exponential growth rate, and can be written as

| (3) |

This is also referred to as the relative fitness. The values of the basic reproductive ratios determine the outcome of the competition for resources. In fact, for equations of the form Equation 2 with arbitrary numbers of mutational variants, only a single stable steady-state exists, with the mutational variant with the largest R0 value converging to a positive value, and all other variant populations converging to zero [37].

The fact that only one dominant strain persists in simple models of selection is known as the principle of competitive exclusion [37]. If the necessary conditions are met, the principle of competitive exclusion mean that mutation events that do not yield a competitive advantage can be neglected, as the selection dynamics quickly drive them extinct. This hold true for most viral systems, where the mutation rate is much slower than the turnover rate. In these systems, the viral populations tend to converge to a single dominant phenotype (the genotype remains heterogeneous, as many genetic mutations do not change the protein expressed by the gene). For cancer models, however, the cells are relatively long-lived, with lifespans comparable to the rate at which mutations are generated. In this case, the population of cancer cells tends to remain heterogeneous, although the fittest variants still dominate [51].

The elements Equation 3 are situation dependent; changing conditions, such as the addition of therapeutic drugs, change the value of R0. The goal of most antiviral, antibiotic, or antitumor therapies is to modify the elements of this equation through the application of appropriate drugs to reduce the value of R0 below 1. This creates a situation of exponential decline for the strain targeted, and the strain is said to be susceptible to the therapy. Conversely, if a particular therapy is unable to reduce R0 below 1 for a particular strain, that strain is termed resistant to the therapy.

Finally, when the values of any individual species in these equations approach zero, the large numbers assumptions necessary for ordinary differential equations modeling are no longer satisfied, and stochastic modeling methods must be used. An excellent example of this type of modeling in the context of early HIV infection can be found in [13]. The behavior of the system at these low numbers make it likely that the number of a particular species may drop to zero, after which it cannot rebound. This phenomenon is known as stochastic extinction, and needs to be considered whenever the trajectory values for any species approach very low levels.

The various mutant species competing for resources are known as quasispecies. A complete tutorial and review of quasispecies dynamics under a variety of circumstances is available in [37].

3. Medical Applications of Evolution

Evolutionary modeling has made a significant impact in the development of treatments for a number of human diseases. While the models are by nature dynamic, most of the applications have, up to this point, been static in nature, focusing either on a probabilistic analysis of initial conditions or a deterministic analysis of steady-state outcomes. Nevertheless, these applications have had dramatic impact. In this section, we introduce three applications of evolutionary modeling which are having significant impact in the treatment of HIV and cancer. This is by no means meant to be an exhaustive review of the use of these models, but is rather a sampling of typical uses of this type of modeling.

3.1. HIV and HAART

The use of evolutionary modeling with perhaps the most significant impact on medicine has to be the mathematical analysis of HIV infection and turnover by Drs. David Ho and Alan Perelson [10]. Before their research, the prevailing wisdom was that HIV was a relatively slow virus, with long life cycles and little cytotoxicity. Using the then-new technology of PCR amplification, the authors of the study measured the concentration of HIV virus in the blood following the application of the potent antiviral drug AZT. By fitting the results to an infection model similar to Equation 2, they were able to obtain an estimate of the virus daily turnover rate for an HIV patient of between 109 and 1010 virions per day, which hardly matched the prevailing wisdom of a slow virus. Using estimates of the base-pair substitution rate for HIV of μ = 3 * 10−5 [24], [41], they were able to use Equation 1 to determine why the use of antiviral drugs was failing to control HIV replication; with the high turnover rates they measured, the probability of a mutant variant with one point mutation (sufficient to yield resistance to a single antiviral drug) existing at the start of therapy was essentially 100%. The same equations were used to calculate how high the number of point substitutions yielding resistance would have to be in order to make resistance unlikely. The answer corresponded to a mutational barrier equivalent to using three antiviral drugs simultaneously, an approach now known as Highly Active Antiviral Therapy, or HAART [36], [39],[42]. The use of HAART in HIV therapy is largely responsible for the transition of the disease from a death sentence to a manageable chronic disease. Research in HIV therapy has continued to expand on the modeling work of Ho and Perelson, driving more modern developments such as the use of genotyping to estimate mutational barriers in drug-experienced patients and even planning antiviral treatment sequencing to minimize the loss of mutational barrier for future antiviral drug options, should resistance occur [12], [25].

3.2. Cancer Chemotherapy

An approach similar to the analysis described above for HIV therapy has also been applied to dose design for cancer treatment [16], [52]. The development of resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent imatinib (Gleevec) in late-stage chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has driven a search for multi-agent chemotherapies capable of eliminating the tumor in the presence of drug-resistance.

CML is a blood-borne cancer, and does not form solid tumors. Early-stage CML responds very well to imatinib, a small-molecule tyrosine-kinase pathway inhibitor [16]. Late-stage cancers, however, respond poorly. This is thought to be due to the pre-existence of drug-resistant strains generated during the high turnover period known as a blast crisis. Komarova and Wodarz performed an analysis similar to that carried out for HIV by Perelson and Ho, using known rates of occurrence for the various mutations that can generate imatinib-resistant strains. Using a variation of Equation 1, the analysis showed a combination therapy using at least two additional chemotherapeutic agents with limited patterns of cross-resistance should yield durable suppressive therapy even in late-stage chronic myeloid leukemia. Such a combination therapy should make the emergence of any multiple-drug resistant cancer strain before tumor eradication unlikely.

3.3. Fitness enhancement for therapeutic viruses

Certain experimental methods are using genetically engineered viruses as therapeutic agents. These viruses are used either alone, for their direct cytotoxic effects on the tumor [33], [3], or in combination, enhancing tumor susceptibility to a secondary chemotherapy [50], [55], [11],[48], [57], [58]. These viruses are usually variants of naturally occurring viruses. In order to enhance their effectiveness as antitumor agents, a common technique is to set up an artificial selection environment, in which enhancing the therapeutic activity of the virus also enhances the fitness (R0) of the virus. Essentially, the stable steady-state of the selection equations is manipulated to be in a beneficial location, and then natural evolutionary dynamics are used as a dynamic optimization method.

An example of this can be found in [18]. In this study, diversity is artificially introduced into a population of human adenoviruses, which are then selected for potency against cultured tumor cells. Adenoviruses are a well-studied virus for use in a variety of gene therapies, and they can be rendered cancer-specific by the deletion of a p53 repressor gene. However, the existing oncolytic virus strains suffer from poor oncolytic characteristics, including insufficient infectivity and cytotoxicity (β and a from Equation 3).

In order to generate a virus lineage with better oncolytic characteristics, the authors of the study set up a natural selection process in two steps. In the first step, they cultured adenovirus from seven separate viral subtypes in four different media of either breast, pancreatic, colon, or prostate cancer cells. The virus was cultured at a very high virus to target cell ratio, to encourage multiple virus to infect the same target cell, a situation with a high probability of generating recombinant daughter viruses. As soon as the cells began to show signs of virus-mediated lysis, the extracellular fluid was harvested and used to culture a fresh set of target cells. By this method, only the viruses exhibiting the fastest lysis would survive, and the viruses exhibiting the strongest infectivity would dominate.

After 20 passages, the selected viruses were purified and examined for significant increase of anti-tumor activity. A mutant virus cultured on the colon cancer cells was found which was more than 1000 times more potent than the parent viruses on the cultured colon cancer cell line, and between 9 and 100 times more potent on all other colon cancer lines tested. It was also oncospecific, lysing the cancerous cell lines at a rate greater than 100 times greater than the infection rate for normal cells. A well-defined evolutionary experiment was therefore able to create a novel virus with significant potential for anti-tumor therapy.

4. Resistance Risk Reduction in HIV

While traditional applications of evolutionary modeling have been largely static in their analysis and treatment approaches, a small number of recent studies have focused on exploiting the transient dynamics of the models. These studies are especially interesting to controls engineers, as the complexity of solutions utilizing transient dynamics of nonlinear equations demand a model-based approach. In the area of HIV, one such study used stochastic models of evolutionary competition to determine the optimal switching pattern for HIV therapy when a patients viral load is controlled below the limit of detection [5]. The models predicted a decrease in the incidence of viral resistance if the treatments were switched every three months, whether or not resistance had emerged. This approach was evaluated in a small clinical trial, with significant success [26].

We have previously presented a second approach utilizing the transient evolutionary dynamics to find optimal therapy switching schedules when resistant virus has already emerged. Although HAART is effective at suppressing HIV virus, antiviral resistance is still problematic; 30–50% of all individuals being treated with a given HAART regime will develop virus resistant to that regimen [40]. Even when the patient switches their antiviral regimen, the resistant viruses remain in the patient’s viral reservoirs forever, and quickly re-emerge if the original regimen is ever reintroduced [7]. Any new regimen must therefore consist entirely of antiviral drugs that have never been used for that patient, and drugs with known cross-resistances with previously used drugs must also be avoided. There are 23 unique antiviral drugs approved for treating HIV, however, because of shared resistance profiles, only 3–7 sequentially usable therapy regimes are possible. Patients who sequentially develop resistant virus to more than two regimens are in danger of running out of effective treatments, which may lead to disease progression and death. Keeping treatment options available is especially important to those patients who have experienced more than one treatment failure.

Earlier work by Bonhoeffer and Ribeiro [2], [42] showed that, for HIV, a resistant virus was most likely to emerge immediately after switching drug therapy and the probability of emergence is directly proportional to viral load at the time of switching. High viral loads increase the risk of early failure by increasing the probability that viruses carrying resistance mutations are randomly generated during replication. An intervention that reduces the viral load prior to introducing a new treatment will reduce the risk of developing resistance to the new treatment, and thereby preserve future treatment options. In our previous works [59], [21], [23], [22], we developed an algorithm to optimize the treatment based on this idea. We present a review of these results here.

Two factors that influence the probability of emergence for a particular resistant viral strain are its relative fitness and genetic distance from existing strains. Mutations that confer resistance usually carry a relative fitness cost in the absence of treatment; they do not replicate as well as the wild-type in these circumstances. If they did not carry this fitness cost, the resistant strains would already be the dominant viral strain before treatment is introduced. In the absence of treatment, the wild virus will dominate due to its increased fit-ness, driving down the population of the resistant strain through competition for target cells. A mutation is effective only if it imparts a resistance to the current drug cocktail and the fitness cost is not so high that it would impair its ability to survive even if the wild type is being suppressed by the medication. Those resistant viruses that can survive are relatively few.

The genetic distance is the Hamming distance or the number of point mutations between the current virus and the virus that is resistant to a particular treatment. Because of the random nature of mutations, viruses with larger Hamming distance are less likely to emerge than those with a smaller one. The likelihood decreases as the power of the Hamming distance. The mutation rate for HIV is relatively large. If the number of mutations necessary to confer resistance to a particular antiviral treatment is 1, the emergence of a resistant virus is almost certain. However if the distance is 4 or greater, the probability of an emergence is vanishing small.

4.1. Fitness and Risk

Bonhoeffer and Ribeiro [2], [42] showed that a resistant virus was more likely to exist at the introduction of a new antiviral regimen than to be generated during its use. This is due to the fact that, during successful suppressive therapy, relatively few viral replication events are occurring, and consequently few mutations. This may be modeled as a stochastic process. If we assume a constant mutation rate, the probability of resistant virus emerging follows a Poisson distribution. The number of trials in this Poisson model is the number of viral replication events; due to the high rate of turnover for HIV, the entire viral population in a given patient can be assumed to turn over once per day. HIV virus does not reside only, or even primarily in the blood; it is found in all the lymphoid tissues as well. Previous studies [17], [4], [54], [56] have calculated the ratio between the viral load measured in the blood and the total viral burden in the patient. If multiple viral strains are present, a resistant virus may arise from any of them, and the total probability must be calculated. Let [v1, v2, …, vn] be the total viral burden for each of the n subspecies of viruses. Let [g1, g2, …gn] be the genetic distances where gi is the genetic distance between virus, vi, and a potential emerging resistant virus, ve. Assuming a constant point mutation rate of μ, the probability of ve existing at time t is:

| (4) |

where vi(t) is the viral burden of the ith subtype present in the patient at the time of introduction of the naive regimen. Fig. 1 shows the relationship between viral load and the risk of resistant mutant emergence. A resistant virus may pre-exist when the genetic distance is 1 or 2, but not if the genetic distance is 3 or higher.

Figure 1.

Resistance emergence risk vs. viral load

4.2. Multistrain Competition Model

As seen from Fig. 1, the key to reducing the risk of a resistant form of the virus evolving is to reduce the viral load. This may be accomplished by leveraging the competition for target cells between the various HIV strains present in the patient. Consider the example described by the following simplified, nonlinear ordinary differential equations:

| (5) |

In this reduced model, there are only two types of viruses, a wild type virus vw and a resistant virus, vr. The dynamics of the various viral reservoirs are approximated by constants, λw and λr. This is a good approximation, as the dynamics of the reservoirs, both uptake and clearance rates, are very slow compared to the rest of the system, and the reservoir sizes can therefore be assumed to be constant for the duration of the treatment. Inputs to the model include one failed treatment, u1 and a previously unused treatment u2. The states include the healthy CD4+ T cells, x, the infected CD4+ T cells; yw, infected by the wild type virus, vw; and yr, infected by the resistant virus, vr. These equations are arbitrarily scalable to any number of viral species. Table 1 shows the values of each parameter in this model used to generate the figures in this paper. These parameters were identified from time-series viral load data from a patient undergoing multiple treatment interruptions as part of the AutoVac study [45]. Details of the identification approach, and parameter data from several other patients, is reported in [22].

Table 1.

Parameter values and definitions for Model 5

| Symbol | Definition (units) | Value |

|---|---|---|

| x | susceptible CD4+ T cells (cells*μL−1) | NA |

| yw | CD4+ T cells infected by wide-type virus (cells*μL−1) | NA |

| yr | CD4+ T cells infected by resistant virus (cells*μL−1) | NA |

| vw | Wild-type Virus ( copies*mL−1) | NA |

| vr | Resistant virus ( copies*mL−1) | NA |

| λ | CD4+ T-Cell Generation Rate (cells*μL−1 * d−1) | 118.17 |

| d | CD4+ T-Cell Death Rate (d−1) | 0.0998 |

| βw | Wild-type infection rate (copies−1 * mL * d−1) | 3.52e-6 |

| βr | Resistant infection rate (copies−1 * mL * d−1) | 3.52e-6 |

| ξw,1 | Efficacy of regimen u1 on the wild-type virus | 90% |

| ξw,2 | Efficacy of regimen u2 on the wild-type virus | 90% |

| ξr,1 | Efficacy of regimen u1 on the resistant virus | 0% |

| ξr,2 | Efficacy of regimen u2 on the resistant virus | 90% |

| u1 | Failed antiviral regimen dosing | {0, 1} |

| u2 | New antiviral regimen dosing | {0, 1} |

| aw | Wild-type virus-induced death rate (d−1) | 0.598 |

| ar | Resistant virus-induced death rate (d−1) | 0.748 |

| λw | Wild-type reservoir re-seeding rate (copies * mL−1 * d−1) | 0.001 |

| λr | Resistant virus reservoir re-seeding rate (copies * mL−1 * d−1) | 0.001 |

| γw | The proliferation rate of wide-type virus | 1000 |

| γr | The proliferation rate of resistant virus | 1000 |

| ωw | Wild-type burst size (copies * cells−1) | 1.136 |

| ωr | Resistant virus burst size (copies * cells−1) | 1.136 |

4.3. Treatment Optimization

Our objective is to find a drug-switching schedule that minimizes the risk of resistant virus pre-existing the new regimen. For patients with only a single previously failed regimen, this can be achieved using interrupted treatment schedules. Our previous works [59], [21], [23], [22] have addressed this problem in detail. Interrupted treatment schedules are avoided due to high rates of treatment failure associated with them. For patients who have failed more than one previous drug regimen, there are two approaches to treatment that can be used to dramatically reduce the risk of subsequent failure, and neither one uses treatment interruptions. The first method cycles through the previously failed regimens before returning to the currently failing regimen. The second method introduces a permuted antiviral regimen consisting of a mix of drugs from the previously failed regimens.

4.3.1. Regimen Cycling

Consider a patient with viral dynamics described by Equation 5 who has developed virus strains vr1 and vr2 resistant to two previous treatment regimens u1 and u2. If the viral strains resistant to those regimens are susceptible to the current regimen, they will have decayed to very low levels, and will take some time to re-emerge. Assuming no cross resistance, the currently dominant viral strain is likely susceptible to the original drug regimen u1 to which the strain vr1 developed resistance. Strictly speaking, so long as R0(vr1, u1) > R0(vr2, u1) and R0(vr1, u2) < R0(vr2, u2), where R0 is the basic reproductive ratio defined as

| (6) |

then a transient viral minimum significantly lower than the steady-state level of viral load may be achieved by this method, as previously reported in [59].

Our approach can be formulated as an optimal control problem in two steps. In the first step, the allowable patterns of treatment cycling where either u1(t) = 1 or u2(t) = 1 at any time t are searched to find a treatment pattern that minimizes the cost function

| (7) |

where P(ve(t) ≠ 0|vi(t)) is the cost function defined by Equation 4. If the genetic distances between the closest strain resistant to regimen u3 and vw, vr1, and vr2, respectively are all equal, this optimization returns the treatment cycling schedule with the largest decrease in total viral load prior to introducing the naive regimen. The second step involves robustly estimating the time at which the minimum in the risk is achieved, and switching to the naive regimen at this point.

Measurement of viral load has a laboratory delay of about 1 day, and involves drawing blood. The most frequently that it would be possible to make these measurements and change the treatment regimen would be once a week. To avoid the rapid evolution of resistance, treatments are always applied at a full therapeutic dose (u* ∈ {0, 1}). This gives a finite set of possible controls, which allows us to exactly solve the optimization problem above using exhaustive search. This can take as long as 0.5 hours on a desktop PC running MATLAB; however, this is far faster than our sampling time, and suffices. Figure 2 shows an example optimal switching schedule for a particular patient with two previously failed regimens.

Figure 2. Multiple Previous Failures: Regimen Cycling.

Shown are the populations of the total viral load (blue), resistant strain 1 (green), and resistant strain 2 (red). By switching between currently failing regimen u2 and previously failed regimen u1, it is possible to achieve a significant reduction in total viral load prior to introducing new regimen u3. Parameters are as in Table 1.

It is worth noting that the assumption that we can generate step changes in the drug concentrations and maintain constant drug levels is a simplification. The drug uptake and clearance dynamics are relatively fast, but the oral administration of the drug can cause “ripple” in the dosage level, with the trough level being potentially clinically significant [8]. However, the exact pharmacokinetics are beyond the scope of this discussion.

4.3.2. Permuted Regimen Introduction

Another approach to treating patients with multiple previously failed regimens is to use a permuted regimen. Although a permuted combination of the component drugs of previously failed regimens can not provide sufficient mutational barrier for long-term suppression, it will lead to a dramatic transient reduction in the viral load and the corresponding resistance risk. This is because, while virus exists which is resistant to each of the previous combination regimens, no large populations of virus exist which are resistant to the novel combination being used. The number of point mutations necessary to confer resistance to the combination regimen is either 1 (for two previously failed regimens) or 2 (for two or more previously failed regimens), so a resistant virus will almost certainly emerge, but the total viral load will drop significantly before this resistant virus has a chance to grow to significant levels. This has been reported previously in [21]; we review these results here.

Assuming that the two previously dominant resistant strains vr1 and vr2 are resistant to drug combinations a+b+c and A+B+C, respectively, then virus resistant to a permuted drug combination such as A+b+c will pre-exist at a rate roughly

| (8) |

where μ is the pointwise mutation rate for HIV and |vA − vr1|H is the number of point mutations in virus variant vr1 necessary to generate a virus vA with resistance to drug A and |vbc − vr2|H is the number of point mutations in virus variant vr2 necessary to generate a virus vbc with resistance to drugs b and c, respectively. Note that these are also the Hamming distances applied to the genetic sequences of the respective viruses. Fig. 3 shows the case where only one point mutation separates the dominant resistant strain from a strain resistant to the permuted regimen. Standard treatment introduces a naive regimen at switch point T1. By introducing a permuted regimen at T1, it is possible to achieve a greater than 2 order-of-magnitude reduction in viral load before introducing the naive regimen at T2. The reduction in risk of subsequent failure which this achieves varies according to the mutational barrier height of the new antiviral regimen, as shown in Figure 1. Table 2 compares the probability of treatment failure for the standard treatment, switching to the new regimen at time T1, with that for the permuted regimen approach, switching at time T2. Results are shown when the new regimen presents mutation barrier heights of 1, 2, or 3 respectively. The mutational barrier height of the permuted regimen is assumed to be 1.

Figure 3. Multiple Previous Failures: Permuted Regimens.

Following the introduction of a permuted regimen, the total viral load transiently crashes (solid lines). By switching to a new treatment regimen at the viral load minimum T2, rebound is prevented and resistance risk is minimized (dashed lines). The mutational barrier of the permuted regimen affects both the minimum time and the achievable reduction in risk.

Table 2.

Probability of resistant strain pre-existence at T1 and T2 for different mutational barriers.

| Mutational Barrier | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Switch Point T1 | 1 | 0.93 | 8.83 * 10−5 |

| Switch Point T2 | 1 | 0.0089 | 3.04 * 10−7 |

The permuted regimen provides insufficient mutational barrier to prevent resistance, so if a switch is not made, the viral load will rebound. The reduction in resistance emergence risk achieved by this intervention depends on the genetic distance of the dominant strain at the switch time to the closest strain with resistance to the naive regimen.

Figure 3 shows a comparison between the optimal switching time T2 where the permuted regimen has a mutational barrier of 1 and , where the mutational barrier is 2. The switching times and achievable viral load minima are quite different, which illustrates the sensitivity of this approach to the estimate of the pre-existing population of resistant virus calculated in Equation 8. In practice, this quantity is difficult to accurately estimate, so a closed-loop approach involving frequent sampling of the viral load will be necessary to robustly find the actual viral load minimum [44].

5. Thymidine-Kinase Mediated Suicide Therapy

Many chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer work by triggering apoptosis, or suicide mechanisms in the cancer cell. The natural evolution of cancer as it progresses is to lose the native apoptosis triggers, so many advanced-stage cancers are resistant to chemotherapeutic agents that work in this manner. Many groups have considered the use of targeted gene therapy in order to reintroduce susceptibility to the tumor; while this has worked well for in Vitro or murine model experiments, the spread of these susceptibility genes in Vivo has never been sufficient to allow for sufficient tumor death to affect survivability [1, 11, 19, 38, 43, 47, 48, 53].

The recent work of Martinez-Quintanilla et al. [27, 28], seeks to overcome this problem using dynamic evolutionary processes. Together with the susceptibility gene to the apoptosis trigger, they also transfect the cells with a resistance gene, providing resistance to another chemotherapeutic agent. This allows them to set up a selection phase using this second chemotherapeutic agent to encourage spread of the susceptibility gene before introducing the suicide trigger. If the spread of the susceptibility genes has been sufficient, then bystander effects could be sufficient to cause the entire tumor to go extinct.

The approach is elegant, but the dynamic nature of the system complicates the implementation. In order to evaluate the potential impact and drawbacks of this approach, we introduce ordinary differential equation models that capture the basic dynamics of this process. We use these models to explore the complications inherent in implementing this approach, both in Vitro and in Vivo. As pancreatic cancer, the target cell line in this study, forms solid tumors, spatial effects are expected to be important, but ODE models should be sufficient to illustrate the necessity of dynamic controls methods in this preliminary study.

5.1. Biological Background

In [27, 28], the authors transfect pancreatic carcinoma cell cancer lines with a plasmid containing two separate genes. The first gene, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) encodes an enzyme which makes the host susceptible to the action of the drug ganciclovir. Ganciclovir is inert in its administered state, but when phosphorylated by the enzyme encoded by HSV-TK, it becomes toxic. It is incorporated into host DNA during synthesis, resulting in apoptosis. It also diffuses into nearby cells, creating a bystander effect by which cells not directly susceptible to ganciclovir can nevertheless be killed by it.

The second gene carried on the plasmid in [28], is multidrug resistance gene 1 (MDR1). This gene encodes for the membrane bound protein P-glycoprotien, As its name suggests, expression of this gene provides resistance to a number of chemotherapeutic agents, especially docetaxel. It functions by interfering with the transport of docetaxel into the host cell. Docetaxel functions by stabilizing existing microtubule structures, causing a scarcity of free tubulin. This results in a situation where new microtubules cannot be formed and mitotic division of cells is disrupted.

The second gene carried on the plasmid on the other study [27] is dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). DHFR is naturally expressed in all cells, and is an enzyme which is critical to the production of folic acid, a precursor of the nucleic acid thymidine. Overexpression of DHFR confers resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent methotrexate (MTX). MTX works by binding to DHFR and preventing the creation of sufficient thymidine for DNA synthesis.

The main characteristic of either drug is to impede the spread of cancerous cells by preventing reproduction. In the case of a solid tumor, where there is a constant competition for nutrients, blood supply, and extracellular matrix, cells susceptible to chemotherapeutic drugs exhibit a much lower fitness than those that have immunity. Thus, susceptible cells, if not eradicated will at most constitute an insignificant (~0%) proportion of the total cell population under selective pressure as time increases.

The pharmacokinetics and toxicity profiles of docetaxel and methotrexate are well characterized [14, 9] and their use in cancer treatment is standard. Docetaxel does not show sufficient antitumor activity when used as a second-line treatment for pancreatic tumors [46], but it is not necessary for the treatment being considered that the selective chemotherapy be able to achieve tumor eradication, merely that it provide sufficient selective pressure to encourage the spread of the transfected cells through the tumor. The dosing required to achieve such selection would be no higher than a standard therapeutic level, and lower doses (with associated lower toxicities) might work as well. The duration of treatment necessary to achieve sufficient spread of the transfected cells will be discussed in the next section. It is not immediately clear whether this will require periods of treatment long enough to cause toxicity-related adverse events; further in Vivo studies would be necessary to evaluate this. The pharmacokinetics and toxicity profile of ganciclovir are also well understood, and it has been well-tolerated in human gene therapy trials using GSV-TK transfection [47].

Tumor cells can gain resistance to chemotherapy through two mechanisms: mutation or transfection of genetically engineered genes. Natural mutations occur as malignant cells constantly alter their phenotype, often obtaining multidrug resistance (MDR) in the process. The pre-existence of resistant cells is highly likely in late-stage pancreatic cancer, and must be assumed. These cells will be strongly selected for following treatment by their respective chemotherapeutic agent.

Following the introduction of transfected cells of either type, the authors treated the tumors with either doctaxel or MTX. Following this selection phase, the tumor was then treated with ganciclovir, and the total reduction in tumor size was measured. While the results were very promising, a number of dynamic issues related to this approach must be solved for this approach to be used in humans. We will illustrate this using dynamical models in the next two sections.

5.2. Non-Replication Competent Delivery Virus

In the studies mentioned above, the transfected tumor cells were transformed separately, then introduced into the tumor by injection. This approach would not be feasible in cancer therapy. In order to use this approach in humans, a delivery virus would need to be developed. The virus would need to come from a vector which was at least partially oncospecific, and could be made either replication incompetent or replication competent. We will consider both cases.

In the replication incompetent case, following the initial inoculation, a fixed number of the tumor cells will carry the two genes. An unknown number of the tumor cells will also carry natural resistance to the chemotherapeutic agents. Consider the system of differential equations

| (9) |

where x(t) are the chemotherapy sensitive/ganciclovir insensitive tumor cells (CS), y(t) are the chemotherapy resistant/ganciclovir insensitive natural resistant tumor cells (CR), and z(t) are the transfected chemotherapy resistant/ganciclovir sensitive resistant tumor cells (ICR). r, λ, and s are the exponential growth rates of the three populations, respectively, and Cx(t), Cy(t), and Cz(t) are the effects of the chemotherapy on the growth of the three populations, respectively. The growth of the total tumor is limited by a plateau population K; it is assumed that this would slowly increase over time, but not within the window of treatment. dx, dy and dz are the natural death rates of the three tumor subtypes, respectively. g(t) is the effect of ganciclovir on the sensitive cells, and is a measure of the strength of the bystander effects. b is a monotonic function of the relative concentration of z, almost certainly sigmoid in nature, which is the dimensionless approximation of likelihood of a particular cell of type x or y having a cell of type z as a nearest neighbor. Obviously, this is the function where ODE modeling is most likely to break down, but it is sufficient for a first investigation, as is a linear approximation of the sigmoid function b.

We assume logistic growth for our tumor. Several studies have shown this to be a good model for the growth of solid tumors, though many more recent studies show better fits for Gompertz growth models [15, 30, 29, 31]. In particular, [31] shows model parameter extraction for a number of logistic and Gompertz models for tumor growth from a murine model studies using several different cancer cell lines. Unfortunately, none of these studies were for a pancreatic cancer cell line, but the methods developed in these papers would work for fitting data from a pancreatic cell line, if that data were gathered. For this study, we chose not to use parameters gleaned from other cell lines, as this would appear misleadingly exact. Instead, we have used a nominal parameter set, with values as shown in Table 3, where the units of time are arbitrary.

Table 3.

Cancer model symbol definitions

| Symbol | Definition | Value |

|---|---|---|

| x | Chemotherapy sensitive/ganciclovir insensitive cells | NA |

| y | Natural chemotherapy resistant/ganciclovir insensitive cells | NA |

| z | Transfected chemotherapy resistant/ganciclovir sensitive cells | NA |

| v | Delivery virus | NA |

| r | x growth rate | 1.0 |

| λ | y growth rate | 1.0 |

| s | z growth rate | 1.0 |

| Cx | Chemotherapy efficacy on x | 95% |

| Cy | Chemotherapy efficacy on y | 5% |

| Cz | Chemotherapy efficacy on z | 5% |

| dx | x natural death rate | 0.1 |

| dy | y natural death rate | 0.1 |

| dz | z natural death rate | 0.1 |

| K | Plateau population | 100 |

| g | Gancilcovir efficacy on z | 90% |

| b | Bystander effect efficacy | 90% |

| β | Viral infection rate | 0.001 |

| k | Virus burst size | 0.5 |

| a | Virus growth rate | 0.1 |

| u | Virus death rate | 0.3 |

The results of administration of chemotherapy following transfection can be seen in Figure 4. Following administration of the chemotherapy, the tumor size x+y+z and the proportion of tumor cells of subtype x both drop dramatically, and then tumor size rebounds as the two resistant populations y and z grow. The relative dominance of these two populations during this phase is entirely determined by their initial values.

Figure 4. Short-time scale effects.

The application of the chemotherapy quickly drives the non-resistant cells extinct. The relative ratios of the induced vs. natural resistant cells at the end of this period depend entirely on their initial ratios. Parameter values are as in Table 3

The success of ganciclovir therapy depends on its bystander effect, which grows in strength according to the proportion of transfected cells z in the total tumor population. The highest probability of tumor eradication is therefore achieved if the patient is switched from the selective chemotherapy agent to the ganciclovir when the maximum ratio of transfected cells z is achieved. Formulated as an optimal control problem, we want to switch from treatment strategy C(t) = 1, g(t) = 0 to strategy C(t) = 0, g(t) = 1 at time ts where t = ts maximizes the cost function:

| (10) |

Once ganciclovir is introduced the success or failure of the treatment at eradicating the tumor will depend on the relative concentration of ganciclovir sensitive cells z and the relative strength of the bystander effect b. Treatment will effect a minimum in the tumor size; if this nadir is small enough to cause stochastic extinction, then the treatment will have been successful. If, however, the tumor rebounds, it will be composed entirely of naturally chemotherapy resistant cells, so a second round of treatment will be impossible. Figure 4 shows treatment switched at the optimal time ts = 36, achieving a minimum tumor burden of 10% of the plateau population.

Since the outcome depends entirely on the maximization of the ratio of transfected cells prior to introducing ganciclovir, for the remainder of the discussion we will only plot the behavior of the tumor prior to introducing ganciclovir. It is worth investigating how the achievable maximum in Equation 10 changes as a function of the parameters in Equation 9. The achievable maximum depends on the relative fitness of the natural resistant cells versus the induced resistant cells. If the natural cells are even marginally more fit, then extended application of the chemotherapy will select for the natural mutants, as seen in Figure 5. The prevalence of ganciclovir-sensitive cells will reach a maximum, then decline. For optimal tumor killing, the ganciclovir should be introduced at this maximum.

Figure 5. Naturally resistant cells more fit.

Continued application of chemotherapy after the susceptible cells go extinct results in the fitter species driving the other remaining species extinct. Parameter values as in Table 3 except dz = 0.15

On the other hand, if the induced resistant cells are more fit, continued application of the chemotherapy will continue to select for them (Figure 6). Introduction of the ganciclovir should be delayed as long as possible in this case for maximum tumor killing. In this case, the limiting factor would be the toxicity of the chemotherapy, which would enforce a maximum tolerable length of administration.

Figure 6. Induced cells more fit.

Continued application of chemotherapy after the susceptible cells go extinct results in the fitter species driving the other remaining species extinct. Parameter values as in Table 3 except dz = 0.05

5.3. Replication-Competent Delivery Virus

An alternative approach is to use a replication competent virus vector to deliver the plasmid. This has considerable advantages from a dynamic perspective. Rather than having the initial value of the induced resistant cells fixed by the inoculation size, the replication competent viruses will continue to spread through the tumor, creating more ganciclovir-sensitive cells until the target cells are depleted.

There are some safety concerns associated with the use of replication competent delivery viruses, but the viruses can be engineered to be highly tumor-specific (using selective processes like those discussed in Section 3.3), and have been used successfully in human trials with very low reported rates of adverse side effects [1, 38, 47], including a trial which used a replication-competent oncospecific adenoviral vector for HSV-TK gene therapy in patients with advanced liver cancer [47], which showed non dose-limited side effects equivalent to mild flu symptoms.

It is not immediately clear whether the natural resistant mutants y would be susceptible to successful infection by the delivery virus. We will independently consider the optimal virus characteristics for both cases.

5.3.1. Non-susceptible natural resistant mutants

If the natural resistant mutants are not susceptible to infection by the delivery virus, then the system is described by the differential equations:

| (11) |

where β is the infection rate of the virus, a is the virus-induced death rate of the transfected cells, k is the burst size of the virus, and u is the natural death rate of the virus.

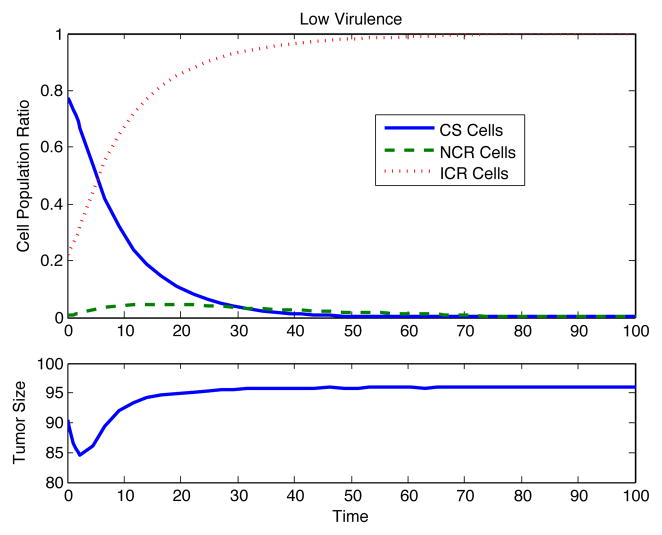

When designing a delivery virus, it is impossible to independently manipulate all the parameters. Assuming the virus is well-adapted to the host, the only way to increase the infection rate is by increasing the burst size, and increasing the burst size necessarily increases the membrane damage done by viral budding, which increases the virus-induced death rate. The choice, therefore, is between fast-spreading, high-virulence delivery viruses or slow-spreading, low-virulence delivery viruses.

A low-virulence virus is shown in Figure 7. In this case, the virus spreads optimally, achieving almost 100% prevalence in the tumor. By contrast, Figure 8 shows a high-virulence virus. In this case, the high virulence virus exhausts its target cells quickly, then fades from dominance, reaching a maximum prevalence of only 50%.

Figure 7. Replication-Competent Delivery Virus, Low Virulence.

The burst-size and cytotoxicity of viruses are fundamentally coupled. A low-virulence, slow-spreading virus can achieve greater spread, due to its lower cytotoxicity. Parameter values as in Table 3 except β = 0.005, a = 0.05, k = 0.5, u = 0.3

Figure 8. Replication-Competent Delivery Virus, High Virulence.

The burst-size and cytotoxicity of viruses are fundamentally coupled. A high-virulence, fast-spreading virus will achieve lower spread, due to its higher cytotoxicity. Parameter values as in Figure 7 except with β = 0.015, a = 0.15

5.3.2. Susceptible natural resistant mutants

If the natural mutants are susceptible to infection by the delivery virus, then the system is described by the differential equations:

| (12) |

and the outcome is shown in Figure 9. In this case, the induced resistant cells always achieve dominance, though a low-virulence vector still accomplishes this faster.

Figure 9. Replication-Competent Delivery Virus, Infects all Cells.

If the delivery virus is able to successfully infect the natural chemotherapy resistant cells, then the induced resistant cells will dominate even with a significant fitness disadvantage. Parameters as in Figure 7

It is clear to see that model-based control techniques will be necessary to fully implement this system. In this short analysis, we have shown that initial inoculations are critical when using non-replication competent delivery virus and that optimal introduction times for ganciclovir depend on the relative fitness of the natural and induced resistant tumor cells. In the case of the replication competent delivery virus, we showed that low-virulence vectors achieved superior theoretical spread. However, we have not fully considered how to optimize the spread of a virus with given fitness parameters. We considered only the case of continuous chemotherapy during the selection phase; with a replication competent virus, it may be that patterns of pulsed chemotherapy achieve superior spread of the plasmid, and consequently improved tumor killing. In general, for an allowable set of chemotherapy schedules  on an open time interval T, we we would want to find ts, C*(t) solving the optimization:

on an open time interval T, we we would want to find ts, C*(t) solving the optimization:

| (13) |

subject to the system dynamics. The design of  , which could explicitly take into consideration the toxicity of the chemotherapies, remains an open problem.

, which could explicitly take into consideration the toxicity of the chemotherapies, remains an open problem.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we reviewed the application of dynamic modeling to evolutionary systems, as applied to medicine. We briefly reviewed the basic mathematical methods used to model mutation and selection processes. We showed some of the ways in which static or asymptotic analysis of these models has contributed in dramatic ways to the practice of medicine and the improving of human health. These applications are broad, and include HIV therapy, cancer treatment, and therapeutic virus development.

We then reviewed two recent approaches which depend on the transient dynamics of the evolutionary system in order to improve the therapeutic outcome. The first is an HIV treatment approach which attempts to dynamically alter the genetic makeup of the viral load prior to introduction of a new antiviral therapy, in order to reduce the risk of resistance evolving to the new therapy. The second is a gene-therapeutic approach to pancreatic cancer treatment which relies on a dynamic selection process to optimally spread a susceptibility gene, hopefully allowing total eradication of the tumor.

In both of these cases, we demonstrated that dynamic modeling was absolutely critical to understanding the complex dynamics of the systems involved. The approaches necessary to achieve the optimal therapeutic outcomes are complicated and non-intuitive. In each case we demonstrated the usefulness of an model-based control formulations in achieving the maximum theoretical medical benefit from each approach.

These applications, while new, do not exist in isolation. Evolutionary systems, especially those concerning drug resistance, are becoming increasingly problematic in medicine. The spread of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) through hospitals and managed-care situations is an increasingly serious problem, and treatment is becoming more difficult [20] and expensive [34]. Optimal treatment approaches, both to minimize the emergence of MRSA and to maximally suppress it when it does emerge[32], will almost certainly be developed. Drug resistance will continue to be a problem in HIV and cancer therapy, and innovative evolutionary model-driven approaches will continue to positively impact those fields. Dynamic modeling of evolutionary processes is an emerging field with important medical applications, and control systems theory is well placed to play a significant role.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rutao Luo, Email: rutaoluo@udel.edu.

LaMont Cannon, Email: lccannon@udel.edu.

Jason Hernandez, Email: jhrnandz@udel.edu.

Michael J. Piovoso, Email: piovoso@psu.edu.

Ryan Zurakowski, Email: ryanz@udel.edu.

References

- 1.Alvarez RD, Curiel DT. A phase I study of recombinant adenovirus vector-mediated intraperitoneal delivery of herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) gene and intravenous ganciclovir for previously treated ovarian and extraovarian cancer patients. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8(5):597–613. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.5-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonhoeffer S, Nowak MA. Pre-existence and emergence of drug resistance in HIV-1 infection. Proc Biol Sci. 1997;264(1382):631–637. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang G, Xu S, Watanabe M, Jayakar HR, Whitt MA, Gingrich JR. Enhanced oncolytic activity of vesicular stomatitis virus encoding SV5-F protein against prostate cancer. J Urology. 2010;183(4):1611–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colgrove R, Japour A. A combinatorial ledge: reverse transcriptase fidelity, total body viral burden, and the implications of multiple-drug HIV therapy for the evolution of antiviral resistance. Antiviral Res. 1999;41(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Amato RM, D’Aquila RT, Wein LM. Management of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: modelling when to change therapy. Antivir Ther (Lond) 1998;3(3):147–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle F, Jovanovic L, Seborg D, Parker RS, Bequette BW, Jeffrey AM, Xia X, Craig IK, McAvoy T. A tutorial on biomedical process control. J Proc Cont. 2007;17:571–594. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997;278(5341):1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher CV, Anderson PL, Kakuda TN, Schacker TW, Henry K, Gross CR, Brundage RC. Concentration-controlled compared with conventional antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. AIDS. 2002;16(4):551–60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita Y, Nakamura T, Aomori T, Nishiba H, Shinozaki H, Yanagawa T, Takagishi K, Watanabe H, Okada Y, Nakamura K, Horiuchi R, Yamamoto K. Pharmacokinetic individualization of high-dose methotrexate chemotherapy for the treatment of localized osteosarcoma. J Chemother. 2010;22(3):186–90. doi: 10.1179/joc.2010.22.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho DD, Neumann AU, Perelson AS, Chen W, Leonard JM, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373(6510):123–6. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishida D, Nawa A, Tanino T, Goshima F, Luo CH, Iwaki M, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Yamamoto E, Ino K, Tsurumi T, Nishiyama Y, Kikkawa F. Enhanced cytotoxicity with a novel system combining the paclitaxel-2′-ethylcarbonate prodrug and an HSV amplicon with an attenuated replication-competent virus, HF10 as a helper virus. Cancer Lett. 2010;288(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang H, Deeks SG, Kuritzkes DR, Lallament M, Katzenstein D, Albrecht M, DeGruttola V. Assessing resistance costs of antiretroviral therapies via measures of future drug options. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1001–1008. doi: 10.1086/378355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalili S, Armaou A. An extracellular stochastic model of early HIV infection and the formulation of optimal treatment policy. Chem Eng Sci. 2008;63(17):4361–4372. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kloft C, Wallin J, Henningsson A, Chatelut E, Karlsson MO. Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model for neutropenia with patient subgroup identification: comparison across anticancer drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(18):5481–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komarova NL, Wodarz D. ODE models for oncolytic virus dynamics. J Theor Biol. 2010;263:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komarova NL, Wodarz D. Drug resistance in cancer: principles of emergence and prevention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(27):9714–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korber BT, Kunstman KJ, Patterson BK, Furtado M, McEvilly MM, Levy R, Wolinsky SM. Genetic differences between blood- and brain-derived viral sequences from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: evidence of conserved elements in the V3 region of the envelope protein of brain-derived sequences. J Virol. 1994;68(11):7467–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7467-7481.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn I, Harden P, Bauzon M, Chartier C, Nye J, Thorne S, Reid T, Ni S, Lieber A, Fisher K, Seymour L, Rubanyi GM, Harkins RN, Hermiston TW. Directed evolution generates a novel oncolytic virus for the treatment of colon cancer. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(6):e2409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurdow R, Schniewind B, Boehle AS, Haye S, Boenicke L, Dohrmann P, Kalthoff H. Resistance developing after long-term ganciclovir prodrug treatment in a preclinical model of NSCLC. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(2B):827–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luna CM, Boyeras Navarro ID. Management of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23(2):178–84. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328336a23f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo R, Piovoso MJ, Zurakowski R. A generalized multi-strain model of HIV evolution with implications for drug-resistance management. Proc American Control Conference. 2009:2295–2300. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo R, Piovoso MJ, Zurakowski R. Modeling-error robustness of a viral-load preconditioning strategy for HIV treatment switching. Proc American Control Conference. 2010:5155–5160. doi: 10.1109/acc.2010.5530483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo R, Zurakowski R. A new strategy to decrease risk of resistance emerging during therapy switching in HIV treatment. Proc American Control Conference. 2008:2112–2117. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansky LM. Forward mutation rate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in a T lymphoid cell line. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 1996;12(4):307–14. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Cajas JL, Wainberg MA. Antiretroviral therapy: optimal sequencing of therapy to avoid resistance. Drugs. 2008;68(1):43–72. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Picado J, Negredo E, Ruiz L, Shintani A, Fumaz CR, Zala C, Domingo P, VilarÛ J, Llibre JM, Viciana P, Hertogs K, Boucher C, D’Aquila RT, Clotet B S.W.A.T.C.H Study Team. Alternation of antiretroviral drug regimens for HIV infection. a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(2):81–89. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Quintanilla J, Cascallo M, Fillat C, Alemany R. Antitumor therapy based on cellular competition. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20(7):728–38. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Quintanilla J, Cascallo M, Gros A, Fillat C, Alemany R. Positive selection of gene-modified cells increases the efficacy of pancreatic cancer suicide gene therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(11):3098–107. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marusić M, Bajzer Z, Freyer JP, Vuk-Pavlović S. Modeling autostimulation of growth in multicellular tumor spheroids. Int J Biomed Comput. 1991;29(2):149–58. doi: 10.1016/0020-7101(91)90005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marusić M, Bajzer Z, Freyer JP, Vuk-Pavlović S. Analysis of growth of multicellular tumour spheroids by mathematical models. Cell Prolif. 1994;27(2):73–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1994.tb01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marusić M, Bajzer Z, Vuk-Pavlović S, Freyer JP. Tumor growth in vivo and as multicellular spheroids compared by mathematical models. Bull Math Biol. 1994;56(4):617–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02460714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBryde ES, Pettitt AN, McElwain DLS. A stochastic mathematical model of methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus transmission in an intensive care unit: predicting the impact of interventions. J Theor Biol. 2007;245(3):470–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng X, Nakamura T, Okazaki T, Inoue H, Takahashi A, Miyamoto S, Sakaguchi G, Eto M, Naito S, Takeda M, Yanagi Y, Tani K. Enhanced antitumor effects of an engineered measles virus edmonston strain expressing the wild-type N, P, L genes on human renal cell carcinoma. Mol Ther. 2010;18(3):544–51. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nathwani D. Health economic issues in the treatment of drug-resistant serious gram-positive infections. J Infect. 2009;59(Suppl 1):S40–50. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(09)60007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowak MA. Evolutionary dynamics: exploring the equations of life. Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowak MA, Bonhoeffer S, Shaw GM, May RM. Anti-viral drug treatment: dynamics of resistance in free virus and infected cell populations. J Theor Biol. 1997;184(2):203–217. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nowak MA, May RM. Virus Dynamics: Mathematical Principles of Immunology and Virology. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oldfield EH, Ram Z, Culver KW, Blaese RM, DeVroom HL, Anderson WF. Gene therapy for the treatment of brain tumors using intra-tumoral transduction with the thymidine kinase gene and intravenous ganciclovir. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4(1):39–69. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.1-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perelson AS, Neumann AU, Markowitz M, Leonard JM, Ho DD. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science. 1996;271(5255):1582–6. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perrin L, Telenti A. HIV treatment failure: testing for HIV resistance in clinical practice. Science. 1998;280(5371):1871–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preston BD, Poiesz BJ, Loeb LA. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1988;242(4882):1168–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2460924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribeiro RM, Bonhoeffer S. Production of resistant HIV mutants during antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(14):7681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenfeld ME, Vickers SM, Raben D, Wang M, Sampson L, Feng M, Jaffee E, Curiel DT. Pancreatic carcinoma cell killing via adenoviral mediated delivery of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Ann Surg. 1997;225(5):609–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199705000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosero E, Zurakowski R. Closed-loop minimal sampling method for determining viral-load minima during switching. Proc of the American Control Conference. 2010:460–461. doi: 10.1109/acc.2010.5530993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruiz L, Carcelain G, Martínez-Picado J, Frost S, Marfil S, Paredes R, Romeu J, Ferrer E, Morales-Lopetegi K, Autran B, Clotet B. HIV dynamics and T-cell immunity after three structured treatment interruptions in chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2001;15(9):F19–27. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saif MW, Syrigos K, Penney R, Kaley K. Docetaxel second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a retrospective study. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(7):2905–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sangro B, Mazzolini G, Ruiz M, Ruiz J, Quiroga J, Herrero I, Qian C, Benito A, Larrache J, Olagüe C, Boan J, Peñuelas I, Sádaba B, Prieto J. A phase I clinical trial of thymidine kinase-based gene therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer gene therapy. 2010 Aug; doi: 10.1038/cgt.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Searle PF, Chen M, Hu L, Race PR, Lovering AL, Grove JI, Guise C, Jaberipour M, James ND, Mautner V, Young LS, Kerr DJ, Mountain A, White SA, Hyde EI. Nitroreductase: a prodrug-activating enzyme for cancer gene therapy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31(11):811–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skurray RA, Firth N. Molecular evolution of multiply-antibiotic-resistant staphylococci. Ciba Found Symp. 1997;207:167–91. doi: 10.1002/9780470515358.ch11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe Y, Kojima T, Kagawa S, Uno F, Hashimoto Y, Kyo S, Mizuguchi H, Tanaka N, Kawamura H, Ichimaru D, Urata Y, Fujiwara T. A novel translational approach for human malignant pleural mesothelioma: heparanase-assisted dual virotherapy. Oncogene. 2010;29(8):1145–54. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wodarz D, Komarova NL. Computational biology of cancer: lecture notes and mathematical modeling. World Scientific Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wodarz D, Komarova NL. Emergence and prevention of resistance against small molecule inhibitors. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15(6):506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolkersdörfer GW, Thiede C, Fischer R, Ehninger G, Haag C. Adenoviral p53 gene transfer and gemcitabine in three patients with liver metastases due to advanced pancreatic carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9(1):16–25. doi: 10.1080/13651820600839555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong JK, Ignacio CC, Torriani F, Havlir D, Fitch NJ, Richman DD. In vivo compartmentalization of human immunodeficiency virus: evidence from the examination of pol sequences from autopsy tissues. J Virol. 1997;71(3):2059–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2059-2071.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao L, Li X, Niu N, Qian J, Xie G, Wang Y. Dichloroacetate (DCA) enhances tumor cell death in combination with oncolytic adenovirus armed with MDA-7/IL-24. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010 Feb; doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu T, Wang N, Carr A, Nam DS, Moor-Jankowski R, Cooper DA, Ho DD. Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in blood and genital secretions: evidence for viral compartmentalization and selection during sexual transmission. J Virol. 1996;70(5):3098–107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3098-3107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zurakowski R, Wodarz D. Modeling and control for in vitro combination therapy using ONYX-015 replicating adenovirus. Proc American Control Conference. 2006:4794–4799. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zurakowski R, Wodarz D. Model-driven approaches for in vitro combination therapy using ONYX-015 replicating oncolytic adenovirus. J Theor Biol. 2007;245(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zurakowski R, Wodarz D. Treatment interruptions to decrease risk of resistance emerging during therapy switching in HIV treatment. Proc 46th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. 2007:5174–5179. [Google Scholar]