Abstract

Background

While surgical epicardial lead placement is performed in a subset of CRT patients, data comparing survival following surgical vs. transvenous lead placement is limited. We hypothesized that surgical procedures would be associated with increased mortality risk.

Methods

Long-term event-free survival was assessed for 480 consecutive patients undergoing surgical (48) or percutaneous (432) LV lead placement at our institution from January 2000 to September 2008.

Results

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were similar between groups. While there was no statistically significant difference in overall event-free survival (p=0.13), when analysis was restricted to surgical patients with isolated surgical lead placement (n=28), event-free survival was significantly lower in surgical patients (p=0.015). There appeared to be an early risk (first ∼3 months post-implantation) with surgical lead placement, primarily in LV-lead only patients. Event rates were significantly higher in LV-lead only surgical patients than in transvenous patients in the first 3 months (p=0.006). In proportional hazards analysis comparing isolated surgical LV lead placement to transvenous lead placement, adjusted hazard ratios were 1.8 ([1.1,2.7] p=0.02) and 1.3 ([1.0,1.7] p=0.07) for the first 3 months and for the full duration of follow-up, respectively.

Conclusions

Isolated surgical LV lead placement appears to carry a small but significant up-front mortality cost, with risk extending beyond the immediate postoperative period. Long-term survival is similar, suggesting those surviving beyond this period of early risk derive the same benefit as CS lead recipients. Further work is needed to identify risk factors associated with early mortality following surgical lead placement.

Keywords: cardiac resynchronization therapy, epicardial lead, left ventricular lead, congestive heart failure

Introduction

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) improves outcomes for patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 35% and QRS duration ≥120 ms.(1) Surgical LV lead placement was employed in early CRT trials,(2-4) but more recent studies (and the current clinical standard of care) have employed transvenous (TV) leads placed in coronary sinus (CS) branches, with implantation success rates of approximately 90%.(5) Despite advances in CS catheter design and implantation technique (6-8) variation in CS anatomy precludes 100% success rates. Consequently, current guidelines acknowledge that surgical lead placement may still be indicated when transvenous lead placement fails.(1)

In the perioperative setting, Class III/IV heart failure is associated with a poorer prognosis. Concerns about surgical morbidity and mortality contributed significantly to the eventual dominance of TV CS lead placement as the procedure of choice. In patients for whom TV lead placement proves impossible, however, the risk inherent in surgical lead placement remains unclear, as available data are limited by sample size, heterogeneous samples, and follow-up duration.(9-15) Subgroup analysis has suggested an increased hazard associated with epicardial leads in diabetic patients.(16) Given the tenuous nature of the patient population and the risks inherent in cardiac surgery, an understanding of the risk increment accrued with surgical versus TV lead placement is essential to inform both clinicians and patients.

Methods

Subjects

All patients who underwent CRT device implant at Brigham and Women's Hospital between January 2000 and September 2008 were identified from the hospital's Electrophysiology Laboratory procedural database, based on the logged procedure name as well as the pulse generator type. A total of 715 possible CRT procedures were identified in a total of 584 patients. The target population was patients in whom CRT was being initiated, excluding those with prior history of CRT. For patients who underwent multiple TV procedures, only the first successful procedure (defined as successful biventricular pacing at discharge) was included (i.e., duration of event-free survival was measured from the point of CRT initiation after this first successful procedure). In 83 cases, the performed procedure involved a lead revision, generator change, or other procedure not involving institution of CRT. In 17 cases, TV lead placement failed but surgical placement was not attempted. In 1 case (TV lead placement), date of death could not be accurately defined (Social Security Death Index and Medical Record data were inconsistent), necessitating exclusion. In 2 cases, a TV CS lead was successfully placed with clinical benefit (including a ≥80% increase in ejection fraction) for months to years prior to rising LV lead impedance or new diaphragmatic stimulation necessitating surgical placement of a new lead. These subjects were also excluded from the analysis, as they did not represent the target population (patients at initiation of CRT). Finally, in 1 case, the initial implant utilized surgical leads, followed by a TV system, after which the abandoned LV surgical lead was reconnected ∼10 years after its placement; this subject was also excluded from analysis.

Of the remaining 480 cases, there were 48 surgically-placed leads from 8 surgeons and 432 CS leads performed by 13 electrophysiologists. Surgical procedures solely for the purpose of LV lead placement comprised 28 of the 48 surgical cases; three surgeons accounted for all of these cases. Of those cases, 4 employed robot assistance (2 of the 4 were converted to open thoracotomy), 5 were mini-thoracotomy, 3 were video-assisted thoracoscopic, and the remaining 16 were performed by standard thoracotomy. In all LV lead only cases, at least two LV epicardial leads were placed.

Clinical variables of interest

Age at CRT implantation, gender, and race were obtained from the medical chart. EF prior to implantation was determined from echocardiogram and/or nuclear stress test reports, as well as from inpatient and outpatient documentation. Pre-implant EF was unavailable for 16 CS cases and 2 surgical cases. Pre-operative electrocardiograms were unavailable in 4 surgical cases and 38 CS cases. Medical records were also reviewed for a history of atrial arrhythmia (atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, and/or atrial fibrillation), as well as the etiology of cardiomyopathy (ischemic vs. non-ischemic). QRS duration prior to implantation was obtained from automated electrocardiogram analysis, with manual review to ensure accuracy.

A composite endpoint of time to death, ventricular-assist device (VAD) implantation, or orthotopic heart transplant was the primary outcome. Transplant and VAD placement were ascertained by query of the electronic medical record. Mortality status was queried both within the electronic medical record, as well as the Social Security Death Index (query performed 11/18/2008).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's Exact Test (2-tailed). Continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon Rank Sum with a 2-sample normal approximation (Z score). Event-free survival within and across groups was assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for both overall mortality, and the composite endpoint of death, VAD, or transplant. Event-free survival using the composite endpoint was also assessed for the first 3 months following CRT initiation, a time by which CRT benefits would be expected in the majority of “responders” based on the literature.(17-19) This mid-term assessment is also in line with the follow-up duration of multiple large-scale CRT trials.(20; 21) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards survival models were constructed to adjust for the contributions of baseline variables (demographic and clinical) to event-free survival for the composite endpoint, for the duration of follow-up and for the previously noted 3 month interval. For Cox analysis, EF was treated as a binomial variable (≤20% vs. >20%), as the continuous variable was skewed. For all comparisons, statistical significance was defined as p<0.05, without adjustment for multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 7.0.1 (SAS Institute, Inc.)

Results

TV CS lead placement was attempted in a total of 480 patients (123 female, 357 male) and was successful in 90% of subjects, with gender-specific success rates of 83% in women and 92% in men (p=0.008). Demographics for subjects with successful lead placement are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Coronary Sinus lead (n=432) |

Surgical Lead (n=48) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Implant (years) | 68.9 [59.8, 76.2] | 65.1 [58.9, 73.0] | 0.07 |

| Gender (% male) | 76 | 58.3 | 0.009 |

| Race (% white) | 90 | 87 | 0.45 |

| Non-ischemic CMP (%) | 47 | 44.7 | 0.76 |

| Atrial Arrhythmia (%) | 41 | 33 | 0.35 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 20 [15, 28] | 20 [15, 26] | 0.31 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 168 [150, 188] | 174 [157, 198] | 0.29 |

Median [95% CI] for age, QRS, and EF

A total of 48 patients underwent surgical lead placement. Subjects referred for surgical lead placement were more evenly distributed by gender (58% male) than were subjects receiving a TV CS lead (76% male). There was a trend toward younger age in surgical patients, compared to TV CS patients. Of note, transvenous CS lead placement prior to surgical lead placement was attempted in 29 of the 48 patients. In 1 of those 29 patients, mitral valve repair was performed at the time of surgical lead placement; for the other 28 patients, unsuccessful TV CS lead placement was followed by isolated surgical LV lead placement without associated valve procedures or bypass. In the 19 of 48 surgical patients who had not had attempted TV CS lead placement, surgical lead placement was performed at the time of another surgical procedure (bypass or valve).

Survival and event-free survival

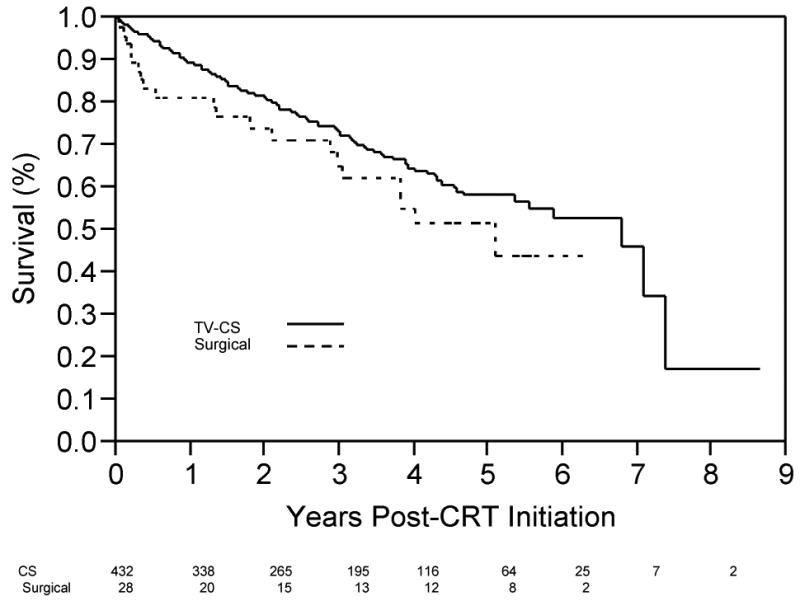

Characteristics of patients who reached the composite endpoint are shown in Table 2. For the TV CS group, events (death, VAD, or transplant) occurred in 142/432 (32.8%) of subjects over a mean follow-up time of 4.9 years (median survival time of 5.9 years). In the surgical cohort, 21/48 (43.8%) patients had events with a mean follow-up time of 3.5 years (median survival time of 4.0 years). Mortality following CRT initiation (Figure 1A) demonstrated a trend toward greater mortality with surgical lead placement (p=0.06, Wilcoxon log rank test), with early divergence of the curves in the first several months post-implantation. Event-free survival (composite endpoint of death, VAD placement, or transplant) demonstrated less separation between lead placement groups (Figure 1B, p=0.13, Wilcoxon Chi Square analysis), but again demonstrated an early divergence for ∼3 months, after which the slope of the survival curve slope paralleled the TV CS group. Of note, mortality accounted for all but 1 event (transplant in a patient who had received a TV CS lead) during this interval.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients reaching the composite endpoint.

| CS TV lead n=142/432 |

Surgical lead n=15/28 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Implant (years) | 71.5 [60.5, 77.3] | 63 [60.0, 73.0] | 0.38 |

| Gender (% male) | 82 | 73 | 0.49 |

| Race (% white) | 93 | 93 | 1.0 |

| Non-ischemic CMP (%) | 33 | 60 | 0.049 |

| Atrial Arrhythmia (%) | 44 | 60 | 0.28 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 20 [15, 25] | 15 [14, 21] | 0.058 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 162 [148.5, 190] | 195 [154, 209] | 0.14 |

Median [95% CI] for age, QRS, and EF

Figure 1.

(A) Survival (free from all-cause mortality) as a function to time post-CRT initiation for patients with TV-CS leads (solid line) and surgical LV leads (dotted line). Number of patients in each group, by year, shown below x-axis. (B) Time post-CRT initiation free from the composite end-point (Transplant, VAD, death), for patients with TV-CS leads (solid line) and surgical LV leads (dotted line). Number of patients in each group, by year, shown below x-axis.

Surgical lead subjects – influence of other surgical procedures

As noted above, patients undergoing surgical LV lead placement consisted of two populations: patients for whom LV lead placement occurred at the time of another surgical procedure (n=20; coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and/or valve repair/replacement; 4 CABG only, 7 valve only, 9 valve + CABG) and patients for whom LV lead placement was the sole surgical indication (n=28). Patients in the LV lead-only group underwent surgical lead placement 1 to 441 days after attempted TV CS placement (median 14 days). Initiation of CRT in these patients was performed on the day of LV lead implantation. In contrast, post-operative CRT initiation tended to be delayed in patients undergoing other surgical procedures, with LV lead activation occurring at a mean interval of 153 days following surgery (range 0-4.3 years). While the only significant difference in baseline variables (Table 3) identified between groups was QRS duration, sample size limited the power of analysis.

Table 3. Baseline Characteristics (Surgical patients).

| Isolated LV lead n=28 |

LV lead + other procedure n=20 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Implant (years) | 62.8 [58.9, 72.8] | 67.3 [56.8, 73.5] | 0.56 |

| Gender (% male) | 60.7 | 55 | 0.77 |

| Race (% white) | 93 | 79 | 0.30 |

| Non-ischemic CMP (%) | 53.6 | 31.6 | 0.23 |

| Atrial Arrhythmia (%) | 39.3 | 25 | 0.36 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 18 [15, 25] | 20 [16, 30] | 0.16 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 182 [164, 207] | 162 [119, 182] | 0.004 |

Median [95% CI] for age, QRS, and EF

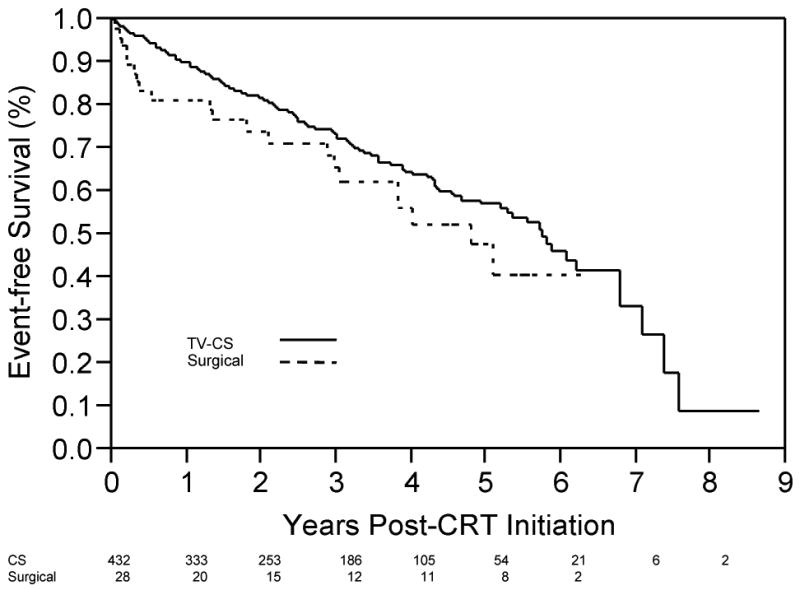

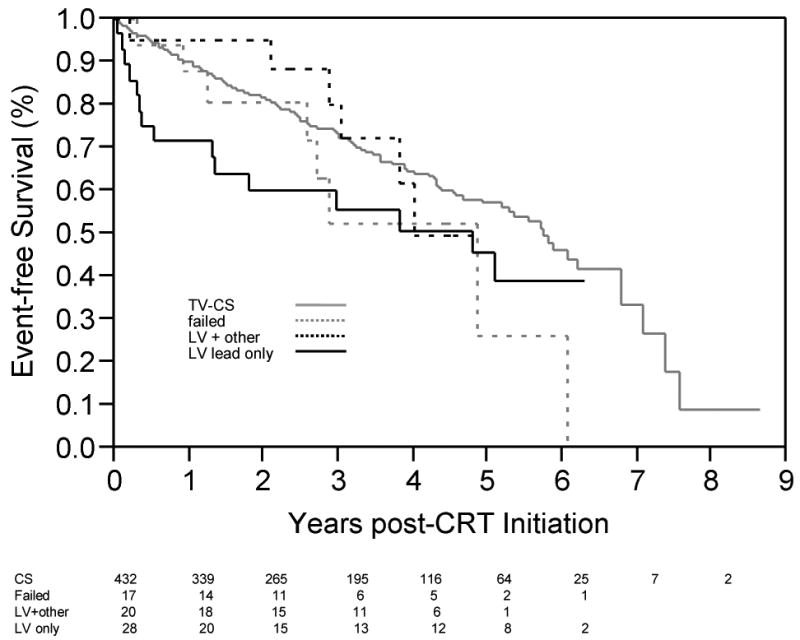

While there was no difference in event-free survival between the two surgical groups (p=0.061, Wilcoxon), there was a clear trend toward higher event rates in the LV lead-only group, with the curves converging at approximately 5 years after CRT initiation (see Figure 2). The early event rate observed in the Figure 1 appeared to be restricted to the LV lead only surgical group (see Figure 2). When time to composite endpoint was evaluated across all 3 groups (LV lead only, combined surgery, and TV CS), a significant difference was observed between groups (p=0.015, Wilcoxon). Survival analysis comparing TV CS lead recipients with patients undergoing isolated LV lead surgical placement found a significant difference in event rates for the composite end point (p=0.006, Wilcoxon). Details of the surgical technique, clinical variables, and outcome for each of the 28 LV-lead surgical cases is given in Table 4.

Figure 2. Event-free survival for individual surgical groups.

Time post-CRT initiation free from the composite end-point (Transplant, VAD, death), for patients who underwent LV-only surgery (black solid line) and LV lead placement at the time of bypass or valve (black dotted line). Patients with a TV-CS lead are shown in solid gray (matches Figure 1B solid line). Patients for whom TV-CS lead attempt failed, and who were not subsequently referred for surgical lead placement (i.e., no CRT performed) are also shown as a function of time after attempted CRT (gray dashed line). Number of patients at risk in each group, by year, is shown below x-axis.

Table 4. LV-only surgical patients – summary of technique, clinical factors, and outcome.

| Age | Surgeon | Technique | Status | Survival (Years) | Cause of Death | EF preop | CMP type | Prior Sternotomy | AF/AFL | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68 | S2 | Thoracotomy | 20% | nonischemic | ||||||

| 88 | S2 | Mini - Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.11 | unknown | 35-40% | nonischemic | 1 | Yes | |

| 66 | S2 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 2.96 | CHF | 15-20% | ischemic | 2 | hematoma | |

| 77 | S2 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.04 | CHF/VF | nonischemic | yes | VT/VF | ||

| 68 | S2 | Mini - Thoracotomy | Deceased | 5.08 | CHF/COPD | 20-25% | nonischemic | yes | respiratory failure, CHF | |

| 81 | S1 | Robot Assisted | Deceased | 1.79 | unknown | 15% | nonischemic | |||

| 74 | S1 | Thoracotomy1 | 15-25% | ischemic | ||||||

| 75 | S1 | Thoracotomy | 40% | ischemic | 1 | yes | ||||

| 79 | S1 | Thoracotomy | 25-30% | ischemic | 1 | ARF, CHF | ||||

| 64 | S1 | Thoracotomy | 20-25% | nonischemic | ||||||

| 78 | S1 | Thoracotomy | ischemic | 2 | ||||||

| 81 | S1 | Thoracotomy1 | Deceased | 3.83 | Malignancy | 15% | ischemic | Yes | ||

| 78 | S1 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.12 | CHF | 10-15% | nonischemic | Lung herniation, CHF, ARF | ||

| 65 | S1 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.29 | CHF | 10-15% | nonischemic | yes | ||

| 71 | S1 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.52 | CHF | 15% | ischemic | |||

| 52 | S1 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.19 | CHF/VT | 10-15% | nonischemic | MCA CVA, ARF, CHF | ||

| 67 | S2 | VATS | 35% | ischemic | 3 | yes | ||||

| 66 | S2 | VATS | Deceased | 0.32 | unknown | 15-20% | nonischemic | yes | ARF | |

| 41 | S1 | Robot Assisted | 15-20% | nonischemic | ||||||

| 61 | S1 | Thoracotomy | Transplant | 2.61 | 25% | ischemic | 1 | yes | ||

| 65 | S2 | VATS | 20-25% | ischemic | 1 | |||||

| 74 | S2 | Mini - Thoracotomy | Deceased | 1.31 | Malignancy | 25% | ischemic | 1 | yes | wound cellulitis |

| 80 | S2 | Mini - Thoracotomy | 15-20% | ischemic | 1 | C diff | ||||

| 61 | S2 | Mini - Thoracotomy | Deceased | 0.36 | unknown | 15% | nonischemic | 2 | Yes | arterial emboli, DVT |

| 54 | S2 | Thoracotomy | 25-30% | nonischemic | ||||||

| 44 | S2 | Thoracotomy | 30% | nonischemic | ||||||

| 64 | S3 | Thoracotomy | Deceased | 1.33 | CHF | 15-20% | ischemic | 1 | ||

| 45 | S2 | Thoracotomy | 25% | nonischemic | CHF |

ARF = acute renal failure, DVT = deep venous thrombosis, C Diff = Clostridium difficile infection, MCA CVA = middle cerebral artery cerebrovascular accident, CHF = congestive heart failure

Case begun with robot, but converted to open thoracotomy for technical reasons.

Of note, our database included 17 patients for whom attempted TV CS lead placement was unsuccessful who did not subsequently receive surgical LV leads, and thus never received CRT. When survival in that small sample was compared to patients who did receive CRT (Figure 2), event-free survival appeared similar to that for patients who receive CS leads for ∼3 years, after which patients who did not receive CRT had increased event rates.

Proportional hazards model

Patients who underwent combined surgical procedures (CABG and/or valve procedure at the time of LV lead placement) were excluded from analysis given the differences observed above between surgical groups. For the full duration of available follow-up, in univariate analysis (Table 5) examining the composite endpoint (VAD/transplant/death), by chi-square testing, only ischemic cardiomyopathy and EF ≤ 20% were statistically significant. Multivariate proportional hazards analysis to adjust for the effects of age, ejection fraction, gender, history of atrial arrhythmia, and type of cardiomyopathy found no significant hazard associated with surgical lead placement (HR 1.3 [1.0, 1.7], p=0.07). Of note, the point estimate for the surgical lead hazard ratio did not change when adjusting for comorbidities (univariate HR 1.3 [1.0, 1.7], p=0.08). In the multivariate proportional hazards model, low ejection fraction was the only factor associated with significant hazard (Table 5). In contrast, when analysis was restricted to the first 3 months following CRT initiation (Table 6), surgical lead placement was associated with significant hazard in both univariate (HR 2.0 [1.3, 3.0], p=0.004) and multivariate (adjusted HR 1.8 [1.1, 2.7], p=0.02) analysis. None of the other evaluated comorbidities were associated with increased hazard at this early post-procedural timepoint.

Table 5. Cox Proportionate Hazards Analysis for the composite endpoint*.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio [C.I.] |

p | Hazard Ratio [C.I.] |

p | |

| Surgical lead | 1.3 [1.0, 1.7] | 0.08 | 1.3 [1.0, 1.7] | 0.07 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1.3 [1.1, 1.5] | 0.005 | 1.2 [1.0, 1.4] | 0.09 |

| History atrial arrhythmia | 1.2 [1.0, 1.3] | 0.16 | 1.1 [1.0, 1.3] | 0.17 |

| Ejection fraction ≤ 20% | 1.2 [1.0, 1.4] | 0.03 | 1.2 [1.0, 1.5] | 0.02 |

| Age | 1.0 [1.0, 1.0] | 0.34 | 1.0 [1.0, 1.0] | 0.28 |

| Male Gender | 1.2 [1.0, 1.5] | 0.08 | 1.1 [0.9, 1.4] | 0.34 |

Analysis restricted to patients who underwent LV lead-only surgical procedures; patients with concomitant bypass or valve procedures were excluded.

Table 6. Cox Proportionate Hazards Analysis for the composite endpoint (first 3 months post-CRT initiation)*.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio [C.I.] |

p | Hazard Ratio [C.I.] |

p | |

| Surgical lead | 2.0 [1.3, 3.0] | 0.004 | 1.8 [1.1, 2.7] | 0.02 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 0.8 [0.5, 1.1] | 0.10 | 0.8 [0.5, 1.1] | 0.20 |

| History atrial arrhythmia | 1.3 [0.9, 1.8] | 0.14 | 1.3 [0.9, 1.9] | 0.12 |

| EF ≤ 20% | 1.1 [0.8, 1.6] | 0.53 | 1.1 [0.8, 1.6] | 0.51 |

| Age | 1.0 [1.0, 1.0] | 0.67 | 1.0 [1.0, 1.0] | 0.67 |

| Male Gender | 0.8 [1.1, 0.6] | 0.21 | 0.9 [0.6, 1.3] | 0.60 |

Analysis restricted to patients who underwent LV lead-only surgical procedures; patients with concomitant bypass or valve procedures were excluded.

Discussion

When CS lead insertion for CRT was first studied, a significant learning curve was demonstrated, with lead placement success rates beginning at 61% and rising to over 90%, and lead dislodgment rates dropping from 30% to 11% over a 6 year period.(22) Anatomical constraints in a subset of patients, however, have resulted in asymptotic success rates with an apparent ceiling of 90-95%. As such, an understanding of the risks of surgical lead placement is essential to guide selection of patients for this procedure.

In this single-center retrospective analysis of survival following initiation of CRT, we found evidence of an early risk of death or need for advanced heart failure therapy (transplant or VAD) following surgical lead placement, compared to percutaneous lead placement, with hazard extending approximately 3 months post-implantation. This hazard did not appear attributable to other factors (age, low ejection fraction, etiology of cardiomyopathy, gender, atrial arrhythmias), but rather, appeared specific to surgical lead placement. This early hazard appears to be restricted to patients who underwent LV lead-only surgical procedures. Of note, however, given the power limitations due to the low number of surgical patients, it is possible that other factors (in particular, atrial arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy etiology) do exert significant effects which are lost in this analysis (Type 2 errors).

Three-month survival post-CRT is a parameter of interest for several reasons. Based on the literature, clinical benefits of CRT should be present in the majority of “responders” by this time. Furthermore, this is reflective of the follow-up interval of several large-scale CRT trials.(20; 21) Earlier studies have demonstrated an apparent early divergence of survival in TV CS vs. surgical LV lead recipients over this same interval of time,(9; 15) but have not examined this interval to determine if the difference was significant.

The present study serves as an extension of a prior report examining the first 112 patients (14 of whom had surgically-placed leads) at our institution following FDA approval of CRT,(15) now with an almost four-fold increase in sample size. While that study found no significant different in 90-day survival between groups, there was a clear trend toward higher mortality in the surgical group (p=0.08). The lack of significance in that study likely reflected inadequate power due to the low sample size.

Possible mechanisms of early hazard

Given clinical criteria for candidacy for CRT (Class III/IV congestive heart failure), patients referred for LV lead placement are generally high risk operative candidates. For instance, historical perioperative mortality rates for CABG in patients with severe LV dysfunction can exceed 30%.(23) Intraoperative events would be expected to influence event rates for a relatively narrow window of time post-procedure; the observed window (3 months) of increased event rates extends beyond what one would typically attribute to perioperative complications, which are generally considered as falling within the index hospitalization. Length of stay for surgical LV lead placement is on generally less than 14 days and averages under a week (13; 14; 24), although longer length of stay has been reported in other studies.(12) It is possible that surgical lead placement may lead to worsening clinical heart failure, either directly or secondary to renal insufficiency or other noncardiac perioperative complication. While it is possible that a prolonged TV CS attempt immediately prior to surgical lead placement could have resulted in acute renal insufficiency and/or decompensated heart failure, surgery followed the TV CS attempt by a median of 14 days, and hazard did not appear higher with shorter intervals between TV CS attempt and operative placement. Further work will be required to determine what factor(s) predispose patients to early events following surgical LV lead placement.

Prior literature examining surgical LV lead placement

Studies to date of surgical LV lead placement reflect a variety of limitations, including mortality assessment restricted to the immediate post-operative period(11; 13) or the first post-procedural year,(12; 14) temporally offset samples (surgical patient population implanted prior to TV CS lead availability compared to TV CS subjects),(12) a high proportion of anteriorly-placed leads in surgical subjects,(12) and surgical samples in which 33% of subjects had received successful CRT via a TV CS prior to surgery.(14) Finally, VAD implantation or transplant were not specifically addressed in previous studies. While higher mortality has been observed with post-thoracotomy patients previously in univariate analysis but that difference was attributed to differences in medical therapy, and did not persist in multivariate analysis.(10)

The recent propensity matched analysis by Ailawadi and colleagues found no statistically significant differences in survival in their analysis, a similar pattern of early mortality in postoperative patients was evident, with 30-day mortality rates similar to that observed in our cohort.(9) Early survival was not explicitly compared in that study.

The use of a composite endpoint (VAD, transplant, or death) offers a better outcome metric than does mortality. Furthermore, the duration of follow-up in the present study is longer than in prior analyses. Finally, the surgical cadre in this analysis is a more congruent population than that in prior comparisons, offering greater insight into the question of event-free survival following surgical lead placement at CRT initiation. Surgical lead placement in patients who have demonstrated clinical benefit from CRT, only to suffer TV CS lead failure, represent a different population, as do patients who undergo LV lead placement at the time of another surgical procedure, as demonstrated in this study.

The trend towards improved event-free survival in combined surgical patients (lead placement at the time of CABG and/or valve procedure), relative to LV lead-only surgical subjects, is difficult to interpret given our inability to capture patients in whom events occurred following surgery but prior to CRT initiation. More detailed examination of these two populations is warranted in order to determine if cardiologists should be more aggressive in encouraging our surgical colleagues to empirically place LV epicardial leads at the time of CABG / valve procedures in patients who, while not currently CRT candidates, may have a future need for CRT. A recent abstract randomizing 178 patients with dysynchrony undergoing CABG to empiric epicardial CRT lead implantation versus CABG alone demonstrated clinical benefit of CRT initiated at CABG.(25) Further work is necessary to determine the role of surgical epicardial lead placement in patients undergoing CABG or valve surgery.

Prior experience and the published literature (26-28) would suggest that surgical leads may be less stable over time than are TV leads, with rising impedance and higher failure rates, although such differences have not been universally observed.(10) However, no patients who received surgical LV leads in this study were subsequently referred for LV lead revision; all subsequent procedures in these patients consisted of generator change or, in a single case, RV lead revision. This is the second study to look at long-term survival of epicardial LV leads.(9) While the nature of data collection in this study limits our ability to draw strong conclusions about the chronic durability of these leads, the results do suggest that they leads are relatively reliable. Further study is warranted to clarify relative durability of surgical LV leads.

Surgical mortality – effect of surgical technique

The mortality associated with surgical CRT lead placement appears to depend in part upon the technique, with mortality rates of 16-33% in the first year.(4; 29) Small studies have examined alternative surgical approaches designed to minimize surgical morbidity and mortality, including video-assisted epicardial lead placement(30) and robotic-assisted surgical techniques,(31; 32) with lower operative mortality than traditional approaches. There is a single-center, single-surgeon comparison of mini-thoracotomy and endoscopic (video- or robot-assisted) approaches in a series of 41 patients reporting ∼70% survival at 12 months; long-term mortality between groups was not directly compared.(33)

Alternative non-surgical methods to achieve LV lead placement in patients for whom TV CS fails are also being developed, including trans-septal LV lead placement(34; 35) and transvenous pericardial lead placement.(36) Further experience with these approaches may obviate the need to perform thoracotomy in patients for whom CS lead placement proves untenable.

Limitations

This analysis spans almost a decade of CRT experience, over the course of which there have been considerable technical hardware advances as well as technical improvements for both electrophysiologists and surgeons. The number of patients in the surgical group is small, particularly when restricted to LV-lead only patients; this limits the power of analysis, and may have resulted in Type 2 errors. Due to the retrospective, observational nature of this analysis, we cannot exclude the presence of unmeasured confounders underlying the observed differences between groups. In particular, subjects for whom TV lead placement failed who were not referred to surgery may differ systematically from those who were referred for surgery. The decision to not refer a patient was at the primary electrophysiologist's discretion, as well as the individual patient; there were not systemic criteria employed. Patients requiring isolated LV lead surgery may represent a sicker cohort than those with TV leads. Certainly, the subjects who underwent LV lead placement at the time of another cardiothoracic surgery procedure represent a different group than those who underwent LV lead-only surgery. As noted above, patients in the former group who had LV leads placed at the time of surgery but did not survive to be referred to electrophysiology for utilization of those leads would not have been captured in our patient selection process, limiting the interpretability of this group. However, we would not expect any such selection bias in the LV-lead only surgical group, who in all cases were referred after a failed CS lead placement attempt.

Given the nature of the patient population (observational, largely a referral population), knowledge of the details of medical comorbidities (e.g., chronic renal failure) and medical management of the patients in this study is limited. Similarly, systematic follow-up echocardiograms were not available on a significant fraction of the subjects, preventing assessment of CRT efficacy as assessed by echocardiographic measures in the two groups.

Conclusions

Both surgical and TV CS LV lead placement are durable methods of providing CRT. Recipients of LV surgical leads comprise a relatively diverse population, particularly those in whom LV lead placement is an “add-on” procedure performed at the time of bypass or valve, versus those for whom LV lead placement is the sole indication for surgery. When analysis is restricted to LV-lead only surgical patients versus TV CS patients, both early (3 month) and long-term event-free survival (using the composite endpoint) are significantly different, with higher event rates in surgical patients. Further work is needed to identify prognostic factors conveying increased risk with surgical lead placement, to characterize the role/indications for LV lead placement at the time of other surgical procedures and to establish the impact of isolated LV surgical leads on quality of life, especially given the upfront risks.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lewis was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation career development grant.

Financial Support: Amy Leigh Miller: NIH/NHLBI T32 Training Grant

Abbreviations List

- CABG

coronary artier bypass graft

- CS

coronary sinus

- CRT

cardiac resynchronization therapy

- CRT-D

cardiac resynchronization / defibrillator

- ICD

implantable cardiac defibrillator

- LV

left ventricle

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- TV

Transvenous

- VAD

ventricular assist device

Footnotes

Relationship with Industry:

Usha Tedrow: Medtronic, Boston Scientific, St Jude, Speaking honoraria, Modest. Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Research grant, Modest.

Bruce Koplan: Medtronic, Boston Scientific, St. Jude – Speaking honoraria, Modest. Biosense Webster, Consultant, Modest.

Laurence Epstein: Medtronic, Boston Scientific, St. Jude – Speaking honoraria, Modest. Biosense Webster, Consultant, Modest.

Eldrin Lewis: Medtronic, Consultant, Modest.

Amy Miller: no relationships/disclosures

Daniel Kramer: no relationships/disclosures

References

- 1.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NAM, III, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) Developed in Collaboration With the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:e1–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auricchio A, Stellbrink C, Sack S, Block M, Vogt J, Bakker P, Huth C, et al. Long-term clinical effect of hemodynamically optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with heart failure and ventricular conduction delay. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:2026–2033. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01895-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins SL, Hummel JD, Niazi IK, Giudici MC, Worley SJ, Saxon LA, Boehmer JP, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients with intraventricular conduction delay and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;42:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins SL, Yong P, Scheck D, McDaniel M, Bollinger F, Vadecha M, Desai S, et al. Biventricular pacing diminishes the need for implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;36:824–827. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA, Wiebe N, Rowe B, Spooner C, Crumley E, Hartling L, et al. Systematic Review: Cardiac Resynchronization in Patients with Symptomatic Heart Failure. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-5-200409070-00101. 381-W-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepard RK, Ellenbogen KA. Challenges and Solutions for Difficult Implantations of CRT Devices: The Role of New Technology and Techniques. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2007;18:S21–S25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkhardt JD, Wilkoff BL. Interventional electrophysiology and cardiac resynchronization therapy: delivering electrical therapies for heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115:2208–2220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leon AR. New tools for the effective delivery of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2005;16 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.50186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ailawadi G, LaPar DJ, Swenson BR, Maxwell CD, Girotti ME, Bergin JD, Kern JA, et al. Surgically placed left ventricular leads provide similar outcomes to percutaneous leads in patients with failed coronary sinus lead placement. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daoud E, Kalbfleisch S, Hummel J, Weiss R, Augustini R, Duff S, Polsinelli G, et al. Implantation Techniques and Chronic Lead Parameters of Biventricular Pacing Dual-Chamber Defibrillators. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2002;13:964–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doll N, Piorkowski C, Czesla M, Kallenbach M, Rastan AJ, Arya A, Mohr FW. Epicardial versus transvenous left ventricular lead placement in patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy: results from a randomized prospective study. Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeon. 2008;56:256–261. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koos R, Sinha AM, Markus K, Breithardt OA, Mischke K, Zarse M, Schmid M, et al. Comparison of left ventricular lead placement via the coronary venous approach versus lateral thoracotomy in patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mair H, Sachweh J, Meuris B, Nollert G, Schmoeckel M, Schuetz A, Reichart B, et al. Surgical epicardial left ventricular lead versus coronary sinus lead placement in biventricular pacing. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2005;27:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puglisi A, Lunati M, Marullo AGM, Bianchi S, Feccia M, Sgreccia F, Vicini I, et al. Limited thoracotomy as a second choice alternative to transvenous implant for cardiac resynchronisation therapy delivery. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah RV, Lewis EF, Givertz MM. Epicardial left ventricular lead placement for cardiac resynchronization therapy following failed coronary sinus approach. Congestive Heart Failure. 2006;12:312–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2006.05568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fantoni C, Regoli F, Ghanem A, Raffa S, Klersy C, Sorgente A, Faletra F, et al. Long-term outcome in diabetic heart failure patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2008;10:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Marco T, Wolfel E, Feldman AM, Lowes B, Higginbotham MB, Ghali JK, Wagoner L, et al. Impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy on exercise performance, functional capacity, and quality of life in systolic heart failure with QRS prolongation: COMPANION trial sub-study. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2008;14:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soliman OI, Theuns DA, ten Cate FJ, Anwar AM, Nemes A, Vletter WB, Jordaens LJ, et al. Baseline predictors of cardiac events after cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with heart failure secondary to ischemic or nonischemic etiology. American Journal of Cardiology. 2007;100:464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soliman OI, Geleijnse ML, Theuns DA, Nemes A, Vletter WB, van Dalen BM, Motawea AK, et al. Reverse of left ventricular volumetric and structural remodeling in heart failure patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. American Journal of Cardiology. 2008;101:651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivero-Ayerza M, Theuns DA, Garcia-Garcia HM, Boersma E, Simoons M, Jordaens LJ. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on overall mortality and mode of death: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Heart Journal. 2006;27:2682–2688. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley DJ, Bradley EA, Baughman KL, Berger RD, Calkins H, Goodman SN, Kass DA, et al. Cardiac resynchronization and death from progressive heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Jama. 2003;289:730–740. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso C, Leclercq C, d'Allonnes FR, Pavin D, Victor F, Mabo P, Daubert JC. Six year experience of transvenous left ventricular lead implantation for permanent biventricular pacing in patients with advanced heart failure: technical aspects. Heart. 2001;86:405–410. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawachi K, Kitamura S, Hasegawa J, Kawata T, Kobayashi S, Mizuguchi K, Nishioka H, et al. Increased risk of coronary artyer bypass grafting for left ventricular dysfunction with dilated left ventricle. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;38:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jutley RS, Waller DA, Loke I, Skehan D, Ng A, Stafford P, Chin D, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic implantation of the left ventricular pacing lead for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Pacing & Clinical Electrophysiology. 2008;31:812–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romanov A, Pokushalov E, Cherniavkiy A, Prohorova D, Goscinska-Bis K, Bis J, Bochenek A, et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting with concomitant cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with ischemic heart failure: results from a multicenter study. European Journal of Heart Failure Supplements. 2010;9:S117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odim J, Suckow B, Saedi B, Laks H, Shannon K. Equivalent Performance of Epicardial Versus Endocardial Permanent Pacing in Children: A Single Institution and Manufacturer Experience. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2008;85:1412–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patwala A, Woods P, Clements R, Albouaini K, Rao A, Goldspink D, Tan LB, et al. A prospective longitudinal evaluation of the benefits of epicardial lead placement for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2009;11:1323–1329. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sachweh JS, Vazquez-Jimenez JF, Schöndube FA, Daebritz SH, Dörge H, Mühler EG, Messmer BJ. Twenty years experience with pediatric pacing: epicardial and transvenous stimulation. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2000;17:455–461. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakker PF, Meijburg HW, de Vries JW, Mower MM, Thomas AC, Hull ML, Robles de Medina EO, et al. Biventricular Pacing in End-Stage Heart Failure Improves Functional Capacity and Left Ventricular Function. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 2000;4:395–404. doi: 10.1023/a:1009854417694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabor S, Prenner G, Wasler A, Schweiger M, Tscheliessnigg KH, Smolle-Jüttner FM. A simplified technique for implantation of left ventricular epicardial leads for biventricular resynchronisation using video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2005;28:797–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jansens JL, Jottrand M, Preumont N, Stoupel E, de Canniere D. Robotic-enhanced biventricular resynchronization: an alternative to endovenous cardiac resynchronization therapy in chronic heart failure. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2003;76:413–417. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeRose JJ, Ashton RC, Belsley S, Swistel DG, Vloka M, Ehlert F, Shaw R, et al. Robotically assisted left ventricular epicardial lead implantation for biventricular pacing. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41:1414–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navia JL, Atik FA, Grimm RA, Garcia M, Vega PR, Myhre U, Starling RC, et al. Minimally Invasive Left Ventricular Epicardial Lead Placement: Surgical Techniques for Heart Failure Resynchronization Therapy. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2005;79:1536–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Gelder BM, Scheffer MG, Meijer A, Bracke FA. Transseptal endocardial left ventricular pacing: an alternative technique for coronary sinus lead placement in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuta B, Lines I, MacIntyre I, Haywood GA. Biventricular ICD implant using endocardial LV lead placement from the left subclavian vein approach and transseptal puncture via the transfemoral route. Europace. 2007;9:1038–1040. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mickelsen SR, Ashikaga H, Desilva R, Raval AN, Mcveigh E, Kusumoto F. Transvenous Access to the Pericardial Space: An Approach to Epicardial Lead Implantation for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2005;28:1018–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]