Abstract

Background

Increasing evidence suggests a relationship between patient expectancies and chemotherapy induced nausea. However, this research has been primarily correlational in nature and has often failed to control for other possible contributing factors. Here, we examined the contribution of patient expectancies to the occurrence and severity of post-chemotherapy nausea using more stringent statistical techniques, namely hierarchical regression, and further extended upon previous research by including quality of life (QoL) in our analysis.

Methods

Six hundred and seventy-one first time chemotherapy patients taking part in a trial comparing antiemetic regimens answered questions regarding their expectancies for experiencing nausea. Patients then completed a diary assessing both the occurrence and severity of their nausea in the 4 days following treatment.

Results

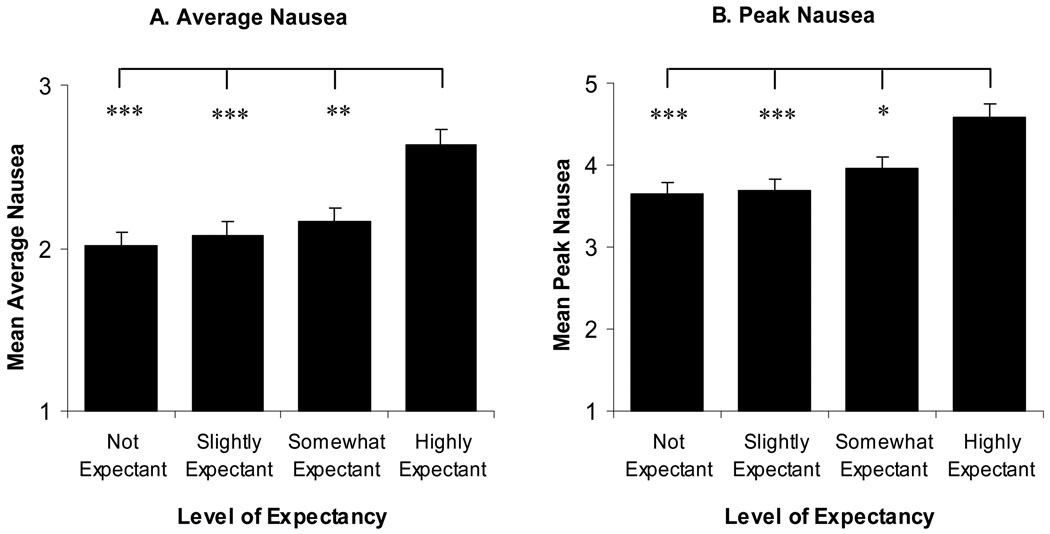

Stronger expectancies for nausea corresponded to greater average and peak nausea following chemotherapy and this was after controlling for age, sex, susceptibility to motion sickness, diagnosis, and QoL. Interestingly, patients classified as highly expectant (1st quartile) experienced significantly greater average and peak nausea than those classified as somewhat expectant, slightly expectant, and not expectant (2nd, 3rd and 4th quartile, respectively), while there were no differences between these lower levels of expectancy. Further, increases in average nausea led to a significant reduction in QoL post-chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Patient expectancies contribute to post-chemotherapy nausea and patients that are highly expectant of experiencing nausea appear to be at particular risk. Interventions that target these patients should reduce the burden of nausea and may also improve QoL.

Keywords: Expectancy, Placebo Effect, Quality of Life, Cancer, Chemotherapy, Nausea

Whilst prevention and control of emesis have improved greatly, nausea continues to be a significant burden to patients undergoing chemotherapy. The vast majority of cancer patients still report experiencing nausea at some point during their chemotherapy treatment1 and it is particularly troublesome for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapies such as cisplatin and doxorubicin2, 3. Nausea is often rated as one of the most severe and debilitating side effects of the treatment 4–6 and can negatively affect patients’ nutritional habits, ability to work, and motivation to follow recommended treatment regimens 6, 7. It is also inherently unpleasant and contributes significantly to poorer quality of life7–11

Given the continued high prevalence of chemotherapy related nausea and its detrimental impact on quality of life, determining what causes this nausea and how it might be reduced remains an important goal for clinicians and researchers alike. Patient expectancies represent one possible causal mechanism that is open to manipulation. Indeed, a growing body of evidence demonstrates a link between patient expectancies for nausea and their actual experience of both anticipatory12, 13 and post chemotherapy nausea1, 14–18. In one study, patients who believed that they were “very likely” to experience severe nausea from their chemotherapy treatment were 5 times more likely to subsequently experience severe nausea than those who believed that they were “very unlikely” to do so18.

This type of evidence for expectancy induced nausea seems to fit in well with current research on the placebo effect in which expectancy is believed to play a key role19–22. Typically this research shows that positive expectancies can lead to beneficial health outcomes., for example pain relief23, 24. However, there is also evidence to suggest that negative expectancies can lead to adverse outcomes, often labeled the nocebo effect25, 26. One study found that when patients participating in a clinical trial of sulfinpyrazone or aspirin for unstable angina were warned about gastrointestinal discomfort they were much more likely to report subsequent gastrointestinal discomfort during treatment and had a 6-fold drop-out rate compared with patients who were not warned about this possibility27.

One limitation to previous research on expectancies and chemotherapy related nausea, however, is that it has been primarily correlational in nature. While this undoubtedly stems from the inherent impossibility of randomly assigning patients to different levels of expectancy, it nonetheless limits the certainty with which we can attribute a causal role to expectancy. Further, it is unclear whether nausea is directly proportional to patient expectancies or whether there is a certain level of expectancy required to produce an effect. If nausea is not directly proportional to patient expectancies it could be the case that those with a high level of expectancy experience more nausea than those with lower levels of expectancy. Conversely, perhaps having low expectancies for nausea has a protective effect and results in less nausea in these patients compared with those who have higher levels of expectancy.

The current study aimed to overcome these limitations in order to determine, with more confidence, whether expectancy contributes to post chemotherapy nausea. To do this, we adopted more conservative statistical techniques, namely hierarchical regression, to evaluate the independent contribution of expectancy to post chemotherapy nausea over and above other potential contributing factors such as, age, gender, susceptibility to motion sickness, and baseline QoL. We also categorized patients into groups according to their level of expectancy to investigate whether a particular level of expectancy either heightened or protected against the occurrence of nausea in patients undergoing chemotherapy. In addition to this, we conducted analyses examining the relationship between pre-treatment QoL and nausea expectancies as well as between post-treatment QoL and post-treatment nausea.

Methods

Participants

The patients were participants in a multicenter trial comparing antiemetic regimens for the treatment of delayed nausea. They were enrolled from 18 private practice oncology groups in the USA between June 12, 2001 and June 11, 2004. Eligible patients were 18 years or older with any cancer diagnosis and were about to receive their first chemotherapy treatment containing doxorubicin and antiemetic prophylaxis with a 5-HT-receptor antagonist, ondansetron, granisetron, or dolasetron plus dexamethasone or the equivalent dose of intravenous methylprednisolone on the day of treatment. Patients were randomized to one of three regimens for control of delayed nausea on Days 2 and 3 following chemotherapy: Arm 1-prochlorperazine 10mg p.o. every 8 hours, Arm 2-any first generation 5-HT3 RA using standard dosage, or Arm 3-prochlorperazine 10 mg p.o. as needed. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Only minimal differences were observed among study arms (see Hickok et al. for additional details2). In the following report, study arm will be statistically controlled for as appropriate.

Measures

At the time of enrolment patients completed a pre-treatment assessment comprising an on-study interview, a quality of life questionnaire, and an expectancy questionnaire. The on-study interview contained questions regarding demographics, previous treatment, and susceptibility to motion sickness. Quality of life was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-General (FACT-G; version 4). It is a widely used and well validated measure for assessing quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment28. The expectancy questionnaire has been previously used by our group29 and contained questions assessing patient expectancies for post-treatment nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and hair loss. Four of these questions assessed expectancies for nausea. One required the patients to rate the likelihood that they would experience nausea after their chemotherapy treatment on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“I am certain I will not have this”) to 5 (“I am certain I will have this”). A second question required the patients to rate the expected severity of their post chemotherapy nausea as “very mild or none at all”, “mild”, “moderate”, “severe”, “very severe”, or “intolerable”. A third question asked the patients to rate their perceived susceptibility to nausea compared with their friends and family as either “more”, “less”, or “the same”. A final question required patients to rate the likelihood of experiencing chemotherapy related nausea compared with other cancer patients with the same diagnosis and undergoing the same treatment, again as “more”, “less”, or “the same”. These four expectancy questions were then combined by averaging z-scores to produce a single expectancy measure.

Post-chemotherapy nausea was assessed via a 4-day patient diary developed by Burish et al.30 and Carey and Burish31 specifically for this purpose. The diary required the patients to rate the severity of their nausea on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (“not at all nauseated”) to 7 (“extremely nauseated”) for the morning, afternoon, evening, and night separately for each day. The diary was then used to calculate average nausea over the four days post-treatment as well as peak nausea, the highest severity rating for nausea at any time in the four days following treatment. At the end of the fourth day patients were again given the FACT-G to complete.

Statistical Analyses

Hierarchical regression was used to determine the predictors of post-chemotherapy nausea. Age, gender, and susceptibility to motion sickness comprised the first step, then diagnosis, followed by study arm, then baseline QoL, and finally expectancy. Diagnosis was dummy coded using breast cancer as the reference group and combining myeloma, endometrial, sarcoma, and bladder cancer patients into a single group because of their low numbers (see below). To assess the impact of level of expectancy on nausea we created four approximately equal groups using quartiles based on the combined expectancy measure. We classified the groups as not expectant (0–25th percentile), slightly expectant (26–50th percentile), somewhat expectant (50–75th percentile), and highly expectant (76–100th percentile). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was then used to compare these groups with follow-up pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni procedure to control the Type I error rate. Hierarchical regression was used to assess the impact of post-chemotherapy nausea on QoL. Here, age and gender were entered as the first step, followed by study arm, then baseline QoL, and then nausea in the final step. Finally, partial correlation was used to assess the relationship between quality of life before treatment and expectancy, controlling for age, gender, susceptibility to motion sickness, and diagnosis. The analyses were conducted separately for average nausea and peak nausea. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 12.0 and results were considered significant when p<0.05.

Results

Six hundred and ninety-one patients enrolled in the study, of which 671 provided evaluable data with an average age of 53 (range 25–90). The majority of these patients were female (94%), white (88%), and had received some college education (59%). Ninety percent had breast cancer, 9% had lymphoma, and the remaining 1% was a mix of myeloma, endometrial, sarcoma, and bladder cancer patients.

Overview of Nausea and Quality of Life

Five hundred and sixty-two (84%) patients reported at least some nausea in the four days following treatment and 165 (25%) reported severe nausea (rating of 6 or 7 on the 7-point scale). Overall, mean nausea on the four days following chemotherapy was 2.2 (SD=1.2) and the mean peak nausea was 4.0 (SD=2.1). Before their first chemotherapy treatment patients had a mean quality of life of 86.3 (SD=13.0), which decreased to 76.3 (SD=15.8) after the treatment.

Expectancy and Nausea

For average nausea, the overall model with age, gender, diagnosis, susceptibility to motion sickness, baseline quality of life, and expectancy included was significant and accounted for 16% of the variance (R2=0.16, F8,659=15.3, p<0.001). Expectancy had a significant impact on average nausea. Specifically, an increase of one standard deviation on the expectancy measure was associated with a 0.27 increase in average nausea after controlling for all other variables in the model (R2 change=0.02, b=−0.27, t659=4.18, p<0.001). Age and baseline quality of life were the only other significant predictors in the model. An increase in age of 10yrs was corresponded to a decrease of 0.3 points on average nausea (b=−0.03, t659=7.12, p<0.001), and a 10 point increase in baseline quality of life corresponded to a 0.1 decrease in average nausea (b=−0.008, t659=2.26, p=0.02).

For peak nausea, the overall model was also significant and accounted for 15% of the variance (R2=0.15, F8,659=14.3, p<0.001). Expectancy was again significant after controlling for all other variables. Here, an increase of 1 standard deviation on the expectancy measure corresponded to a 0.43 increase in peak nausea (b=−0.43, t659=3.86, p<0.001). As with average nausea, age and baseline quality of life were also significant predictors. A 10yr increase in age was associated with a 0.51 decrease in peak nausea (b=−0.05, t659=6.97, p<0.001). A 10 point increase in baseline quality of life corresponded to a 0.1 decrease in peak nausea (b=−0.01, t659=1.98, p<0.048). In addition, lymphoma patients reported less 0.84 points less peak nausea than breast cancer patients (b=−0.84, t659=2.28, p<0.02). Overall, expectancy accounted for 2% of the variance in both average nausea and peak nausea after controlling for all other variables.

Level of Expectancy and Nausea

Figure 1A shows average nausea across the different levels of expectancy. The ANCOVA, with age, gender, susceptibility to motion sickness, diagnosis, baseline quality of life, and study group as covariates, revealed that average nausea differed significantly as a function of level of expectancy (F3,658=8.9, p<0.001). Using pairwise comparisons, highly expectant patients reported significantly higher levels of average nausea than all other levels of expectancy. Specifically, highly expectant patients reported average nausea as 0.62 points higher than not expectant patients (t658=4.49, p<0.001), 0.56 points higher than slightly expectant patients (t658=4.12, p<0.001), and 0.47 points higher than somewhat expectant patients (t658=3.61, p=0.002). There were no significant differences in average nausea between somewhat expectant, slightly expectant, and not expectant patients (highest t659=1.18, p=1).

Figure 1.

Covariate adjusted mean (+SEM) average (A) and peak (B) nausea by level of expectancy. Highly expectant individuals reported both more average nausea and higher peak nausea than all other expectancy levels, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. No other differences were significant.

Figure 1B shows peak nausea for each level of expectancy. As with average nausea, the ANCOVA revealed significant differences in peak nausea as a function of level of expectancy (F3,658=6.5, p<0.001). Highly expectant patients reported peak nausea 0.94 points higher than not expectant patients (t658=3.88, p=0.001), 0.91 points higher than slightly expectant patients (t658=3.76, p=0.001), and 0.63 higher than somewhat expectant patients (t658=2.81, p=0.03). Again there were no differences between somewhat expectant, slightly expectant, and not expectant patients in terms of peak nausea (highest t658=1.41, p=0.96)

Expectancy and Pre-treatment Quality of Life

The partial correlation between expectancy and pre-treatment quality of life was significant (r=−0.29, t660=7.79, p<0.001). This means that stronger expectancy for post-chemotherapy nausea was associated with lower quality of life before treatment.

Impact of Nausea on Post-treatment Quality of Life

The overall model, with age, gender, baseline quality of life, average nausea, and peak nausea included was significant and accounted for 55% of the variability in post-chemotherapy quality of life (R2=0.55, F8,657=100, p<0.001). The only two significant predictors in the final model (Table 2) were baseline quality of life (b=0.58, t657=17.6, p<0.001) and average nausea (b=−5.1, t657=8.80, p<0.001). This means that even after controlling for age, gender, diagnosis, baseline quality of life, study group, and peak nausea, a 1 point increase in average nausea corresponded to a 5 point decrease in post-chemotherapy quality of life. Peak nausea was marginally non-significant (b=−0.65, t657=1.92, p=0.056). Together, average and peak nausea accounted for 20% of the variability in post chemotherapy quality of life (R2 change=0.20, F2,657=143, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Final step in the hierarchical regression of predictors of quality of life after chemotherapy treatment.

| Quality of Life | b | SE | β | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| Gender | 1.09 | 2.61 | 0.02 | 0.68 |

| Lymphoma† | −0.16 | 1.99 | 0.00 | 0.94 |

| Other Diagnosis† | −5.71 | 5.53 | −0.03 | 0.30 |

| Baseline QoL*** | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.47 | <001 |

| Study Group | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Average Nausea*** | −5.11 | 0.58 | −0.40 | <001 |

| Peak Nausea | −0.65 | 0.34 | −0.09 | 0.056 |

Dummy coded with breast cancer as the reference group.

Significant at p<0.001.

Discussion

As with previous studies1, 14–18, patient expectancies for nausea prior to chemotherapy were a significant predictor of the actual occurrence of nausea after treatment. Although expectancies accounted for only 2% of the variance in both average and peak nausea, this was after controlling for age, gender, susceptibility to motion sickness, and quality of life. As such, these results show an independent contribution of expectancy to post-chemotherapy nausea and thereby provide strong support for expectancy as a causal factor in chemotherapy related nausea.

A novel and interesting finding was that patients classified as highly expectant of nausea experienced higher levels of both average and peak nausea than all other levels of expectancy. Further none of the other levels, somewhat expectant, slightly expectant, and not expectant, differed significantly from one another. This suggests that nausea is not necessarily directly proportional to expectancies. Instead, in this case, it appears as though those that are highly expectant about experiencing nausea are particularly at risk, while lower levels share a similar decreased risk. This was also after controlling for age, gender, susceptibility to motion sickness, and quality of life, and again points to a causal influence of expectancy on post chemotherapy nausea.

A second novel finding was that stronger expectancies for nausea were associated with lower quality of life before treatment. Here, the direction of causality is uncertain. It is possible that having strong expectancies for nausea following chemotherapy could detract from quality of life before treatment by creating apprehension and stress regarding the treatment. Conversely, it could be that those with lower quality of life before treatment are in a poorer state of health and therefore expect to be affected more by the chemotherapy treatment.

Increases in average nausea resulted in poorer quality of life post-treatment, a result also consistent with previous research7–11. Here, a one point increase in average nausea corresponded to a 5 point decrease in quality of life. Interestingly, peak nausea did not have a significant impact on quality of life after controlling for average nausea. This tends to suggest that the continued presence of nausea has a more debilitating impact on chemotherapy patients’ quality of life compared with a severe bout of nausea. Average nausea and peak nausea independently of other variables accounted for 20% of the variability in post chemotherapy QoL, a very large effect. Clearly, not only does nausea remain prevalent, it also continues to be a significant burden to cancer patients’ quality of life.

Given the current findings, patient expectancies reflect a possible point of intervention to reduce chemotherapy induced nausea as well as to improve cancer patients’ quality of life. A variety of studies in areas other than oncology have already shown that expectancy manipulations can have a beneficial impact on health outcomes. Perhaps most relevant is evidence that enhancing positive expectancies can lead to decreased postoperative nausea in patients undergoing major gynecological surgery32 and protect against seasickness in naval cadets33. However, these types of manipulations may be more difficult to implement for cancer patients. First, it would be unethical to provide patients with unrealistically low expectancies regarding the likelihood of experiencing nausea as a result of their chemotherapy. Second, in addition to what cancer patients are told to expect from their treating health professionals, they will also draw on information from their family, friends, and the media. As such, any successful expectancy manipulation would have to consider the source of the patient’s expectancies and the significance attributed to that source before attempting to adjust any maladaptive expectancies.

The finding that highly expectant patients experience more nausea than not expectant, slightly expectant, and somewhat expectant patients, and that these latter three did not differ significantly from each other may provide one answer. It suggests that completely eradicating expectancies for nausea is not necessary to gain a significant clinical improvement. For example, if a patient was initially highly expectant but through discussion, or some other manipulation, became somewhat expectant, a significant decrease in both average nausea and peak nausea would be expected with a corresponding improvement in quality of life. Further reducing these expectancies to the level of slightly expectant, however, would produce only minimal additional benefit. Thus, a successful intervention might focus on patients that are highly expectant of experiencing nausea with the aim reducing these maladaptive expectancies rather than removing all expectancy. In doing so, the patient would remain aware that there is a possibility of experiencing nausea, thereby avoiding any ethical concerns regarding giving patient’s unrealistically low expectations of experiencing nausea. Further, a small reduction in expectancy is likely to be much easier to achieve than convincing a highly expectant patient that he/she is very unlikely to experience nausea following chemotherapy.

One possibility along these lines is to include a discussion of the patient’s expectancies regarding side effects as part of the chemotherapy education. This would allow for the identification of highly expectant patients and provide an excellent opportunity to discuss and challenge these potentially maladaptive expectancies. Given the relationship between expectancy and pre-treatment quality of life, reducing strong expectancies for nausea during chemotherapy education may also improve patients’ pre-treatment quality of life. To the best of our knowledge, patient expectancies are rarely, if ever, addressed in chemotherapy education.

Table 1.

Final step in the hierarchical regression of predictors of post chemotherapy nausea.

| A) Average Nausea | b | SE | β | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age*** | −.03 | .01 | −.27 | <001 |

| Gender | .13 | .28 | .02 | .65 |

| Motion Sickness | .02 | .10 | .01 | .84 |

| Lymphoma† | −.40 | .21 | −.10 | .06 |

| Other Diagnosis† | .42 | .60 | .03 | .48 |

| Study Group | .03 | .05 | .02 | .53 |

| Baseline QoL* | −.01 | .00 | −.09 | .024 |

| Expectancy*** | .27 | .06 | .17 | <001 |

| B) Peak Nausea | b | SE | β | Sig. |

| Age*** | −.05 | .01 | −.26 | <001 |

| Gender | −.10 | .49 | −.01 | .83 |

| Motion Sickness | .11 | .17 | .02 | .52 |

| Lymphoma†* | −.84 | .37 | −.12 | .023 |

| Other Diagnosis† | .20 | 1.03 | .01 | .85 |

| Study Group | .13 | .09 | .05 | .17 |

| Baseline QoL* | −.01 | .01 | −.08 | .048 |

| Expectancy*** | .43 | .11 | .15 | <001 |

Dummy coded with breast cancer as the reference group.

Significant at p<0.05,

Significant at p<0.001.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant U10CA 37420 from the National Cancer Institute, USA. Ben Colagiuri is a recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award. The authors wish to thank Phyllis Butow, PhD MClinPsych MPH (Medical Psychology Research Unit, School of Pscyhology, University of Sydney), Robert Boakes, PhD (School of Psychology, University of Sydney), and Luana Colloca, MD PhD (University of Turin Medical School, University of Turin) for their helpful comments on drafts.

References

- 1.Roscoe JA, Hickok JT, Morrow GR. Patient expectations as predictor of chemotherapy-induced nausea. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02895775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-receptor antagonists versus prochlorperazine for control of delayed nausea caused by doxorubicin: a URCC CCOP randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:765–772. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70325-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, et al. Nausea and emesis remain significant problems of chemotherapy despite prophylaxis with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 antiemetics: a University of Rochester James P. Wilmot Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program Study of 360 cancer patients treated in the community. Cancer. 2003;97:2880–2886. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carelle N, Piotto E, Bellanger A, et al. Changing patient perceptions of the side effects of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer. 2002;95:155–163. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin AM, Butow PN, Coates AS, et al. On the receiving end. V: Patient perceptions of the side effects of cancer chemotherapy in 1993. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:189–195. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klastersky J, Schimpff SC, Senn HJ. Supportive Care in Cancer. New York: Marcel Deckker; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osoba D, Zee B, Warr D, et al. Effect of postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting on health-related quality of life. The Quality of Life and Symptom Control Committees of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s005200050078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballatori E, Roila F. Impact of nausea and vomiting on quality of life in cancer patients during chemotherapy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:46–58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballatori E, Roila F, Ruggeri B, et al. The impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on health-related quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen L, de Moor CA, Eisenberg P, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and impact on patient quality of life at community oncology settings. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindley C, Hirsch J, O'Neill C, Transau M, et al. Quality of life consequences of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 1992;1:331–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00434947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR. The role of patients' expectations in the development of anticipatory nausea related to chemotherapy for cancer. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2001;28:843–850. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery GH, Tomoyasu N, Bovbjerg DH, et al. Patients' pretreatment expectations of chemotherapy-related nausea are an independent predictor of anticipatory nausea. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998 Spr 1998;Vol 20(2):104–108. doi: 10.1007/BF02884456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haut MW, Beckwith BE, Laurie JA, Klatt N. Postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1991;9:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA, Redd WH, et al. Nonpharmacologic factors in the development of posttreatment nausea with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer. 1988;61:379–385. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880115)61:2<379::aid-cncr2820610230>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH. Pre-infusion expectations predict post-treatment nausea during repeated adjuvant chemotherapy infusions for breast cancer. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2000;5:105–119. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes VA, Watson PM, McDaniel RW, et al. Expectation and occurrence of postchemotherapy side effects: nausea and vomiting. [see comment] Cancer Pract. 1995;3:247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roscoe JA, Bushunow P, Morrow GR, et al. Patient expectation is a strong predictor of severe nausea after chemotherapy: a University of Rochester Community Clinical Oncology Program study of patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:2701–2708. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirsch I. Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am Psychol. 1985;40:1189–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirsch I. The placebo effect: An interdisciplinary exploration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. Specifying nonspecifics: Psychological mechanisms of placebo effects; pp. 166–186. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirsch I. How expectancies shape experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart-Williams S, Podd J. The Placebo Effect: Dissolving the Expectancy Versus Conditioning Debate. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:324–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colloca L, Benedetti F, Colloca L, Benedetti F. Placebos and painkillers: is mind as real as matter? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nrn1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery GH, Kirsch I. Classical conditioning and the placebo effect. Pain. 1997;72:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, et al. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. [see comment] JAMA. 2002;287:622–627. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn RA, Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26:607–611. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers MG, Cairns JA, Singer J, Myers MG, Cairns JA, Singer J. The consent form as a possible cause of side effects. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1987;42:250–253. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Hickok JT, et al. The efficacy of acupressure and acustimulation wrist bands for the relief of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. A University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program multicenter study. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2003;26:731–742. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burish TG, Carey MP, Krozely MG, et al. Conditioned side effects induced by cancer chemotherapy: prevention through behavioral treatment. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:42–48. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey MP, Burish TG. Etiology and treatment of the psychological side effects associated with cancer chemotherapy: A critical review and discussion. Psychol Bull. 1988;104:307–325. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.104.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams AR, Hind M, Sweeney BP, et al. The incidence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients exposed to positive intra-operative suggestions. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:340–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb14190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eden D, Zuk Y. Seasickness as a self-fulfilling prophecy: Raising self-efficacy to boost performance at sea. J Appl Psychol. 1995;80:628–635. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.80.5.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]