Abstract

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED) is a group of rare multisystemic genetic syndromes that affects ectodermal structures such as skin, hair, nails, teeth and sweat glands. The authors present a case of a child with ocular and dermatological signs of HED along with severe involvement of other multiple organ systems. The family history could be traced to four generations and there was an observed trend of increase in severity of signs and symptoms occurring at younger age. The purpose of this case report is to create awareness in ophthalmic community of its diagnosis and clinical manifestations. This case highlights the role of multidisciplinary approach for management of systemic disease, genetic evaluation of affected individuals and carriers and genetic counselling.

Background

Ectodermal dysplasia (ED) is a group of rare multisystemic genetic syndromes that affects ectodermal structures such as skin, hair, nails, teeth and sweat glands. It may be hidrotic or hypohidrotic type. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED) is the most common subtype. We present a case of a child with ocular and dermatological signs of HED along with severe involvement of other multiple organ systems. The family history could be traced to four generations and there was an observed trend of increase in severity of signs and symptoms occurring at younger age. The purpose of this case report is to create awareness in ophthalmic community of its diagnosis and clinical manifestations. This case highlights the role of multidisciplinary approach for management of systemic disease, genetic evaluation of affected individuals and carriers and genetic counselling.

Case presentation

An 18-month-old male child was referred to our ophthalmology department with complaints of photophobia and watering in both eyes for past few months. On examination, the child had features of dry eyes with bulbar conjunctival injection, irregular corneal surface and punctuate epithelial erosions with positive fluorescein staining. The tear meniscus and tear film break-up time could not be evaluated due to young age of the child. The eyelashes and eyebrows were very scanty.

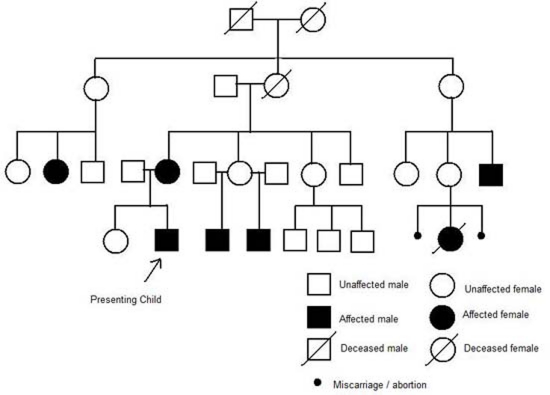

The skin around the eyes and face was thin, dry and eczematous. The scalp hair was thin, brittle and sparse (figure 1A,B). The child had delayed dentition with few malformed teeth (figure 2). He also had micrognathia and mild scoliosis.

Figure 1.

(A) Child with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (clinical features – dry, eczematous skin; sparse eyelashes and eyebrows). (B) Mother and child with features of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (dry, brittle, sparse hair; dry skin).

Figure 2.

Hypodontia with wide spaced pointed teeth.

The child had suffered from diarrhoea and vomiting most of his life and his weight was less than average for his age. The child was assessed by paediatric gastroenterologist and was found to have gastro-oesophageal reflux disease with biopsy proven oesophagitis and confluent pancolitis due to dysplastic mucosal lining.

The child had speech and breathing difficulties due to bilateral vocal cord palsy. He had also developed cellulitis of his left ear caused by Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus and eczema herpeticum of the chest wall.

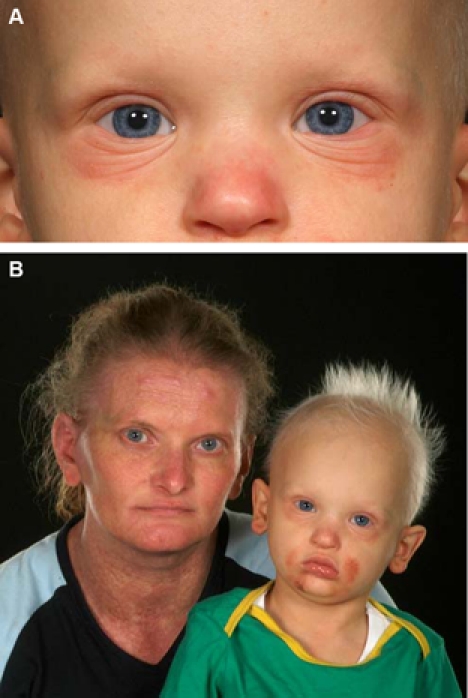

The mother of the child had dry skin, sparse hair and hypodontia (figure 1B).The family history in this case could be traced to four generations and all the affected family members including females had features of HED (figure 3). He was referred to a Geneticist and X linked recessive inheritance was established.

Figure 3.

Genogram of X linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.

Investigations

The diagnosis of HED is mainly clinical and based on family history. Carrier testing is possible for the X linked and autosomal recessive forms if the disease-causing mutation in the family is known.

Skin biopsy of hypothenar eminence demonstrate an absence or hypoplasia of eccrine sweat glands.

Sweat pore count using starch-iodide powder demonstrate absent pore in affected individuals and a mosaic pattern (areas of normal and absent pores) in carrier females.

Prenatal diagnosis using genetic mutation analysis is possible for pregnancies at increased risk if the disease-causing mutation in the family is known.

Indirect prenatal diagnosis may be performed by linkage analysis applied to chorionic villus samples at the 10th week of gestation for some EDs. Fetal skin biopsy may help identify the presence of decreased numbers of eccrine sweat glands.

Treatment

For the relief of eye symptoms, the child was prescribed with dark glasses and lubricating eye drops during the day and gel at night. The hydrocortisone cream was advised for relief of eczema around eyelids.

Discussion

Pure EDs are manifested by defects in ectodermal structures alone, while ED syndromes are defined by the combination of ectodermal defects in association with other anomalies. The most common EDs are X linked recessive HED (Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome) and hidrotic ED (Clouston syndrome). HED is estimated to affect at least 1 in 17 000 people worldwide. HED is a heterogenous group of disorders and so far more than 192 distinct disorders have been described.

Genetics and mode of inheritance

Mutations in the EDA, EDAR and EDARADD genes cause HED.1

The EDA, EDAR and EDARADD genes provide instructions for making proteins that work together during embryonic development. These proteins form part of a signalling pathway that is critical for the interaction between two cell layers, the ectoderm and the mesoderm. In the early embryo, these cell layers form the basis for many of the body’s organs and tissues. Mutations in the EDA, EDAR or EDARADD gene prevents normal interactions between the ectoderm and the mesoderm and impair the normal development of hair, sweat glands and teeth. The improper formation of these ectodermal structures leads to the characteristic features of HED.

HED may be inherited as X linked recessive, autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant pattern.

Most cases are caused by mutations in the EDA gene, which are inherited in an X linked recessive pattern. Males are affected by X linked recessive disorders much more frequently than females as males have only one X chromosome and one altered copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition. In females (who have two X chromosomes), a mutation must be present in both copies of the gene to cause the disorder.

In X linked recessive inheritance, a female with one altered copy of the gene in each cell is carrier. Female carriers in HED have mild features as few missing or abnormal teeth, sparse hair and some problems with sweat gland function. Female carriers may display a blaschkoid distribution of hypohidrosis (the lesions arranged in whorls and streaks corresponding to the lines of Blaschko which represent pathways of epidermal cell migration and proliferation during the development of the fetus) as a result of lyonisation and somatic mosaicism for the abnormal X chromosome.

Less commonly, HED results from mutations in the EDAR or EDARADD gene. EDAR mutations can have an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, and EDARADD mutations have an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. In autosomal dominant inheritance, one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. In autosomal recessive inheritance, two copies of the gene in each cell are altered. Most often, the parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder are carriers of one copy of the altered gene but do not show signs and symptoms of the disorder.

Clinical presentations of HED

Several ED syndromes may manifest in association with midfacial defects, mainly cleft lip, cleft palate or both. The three most commonly recognised entities are (1) ED, ectrodactyly and clefting (EEC) syndrome, (2) Hay–Wells syndrome or ankyloblepharon, ED and cleft lip/palate syndrome and (3) Rapp-Hodgkin syndrome, all of which are caused by mutations in the TP63 gene. HED results in abnormal development of structures including skin, hair, nail, teeth, eyes and sweat glands (table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

| System involved | Clinical features |

|---|---|

| Skin | Hypohidrosis, anhidrosis, heat intolerance, fever, dry, cracked skin, eczema, dermatitis |

| Hair | Hypotrichosis, dry, brittle, light coloured hair |

| Nail | Deformed, brittle, thin, ridged nails |

| Teeth | Hypodontia, anodontia, delayed dentition, wide spaced, pointed, discoloured teeth |

| Facial features | Frontal bossing, saddle nose, malar hypoplasia, mandibular hypoplasia |

| Otolaryngologic features | Hypoplastic alae nasi, atrophic rhinitis, ozena, pharyngitis, laryngitis, laryngeal mucous hyposecretion, vocal cord palsy, voice changes |

| Ophthalmic features | Dry eyes, corneal dryness, pannus, vascularisation and scarring, ankyloblepharon, blepharitis, trichiasis, loss of eyelashes and eyebrows, malformed meibomian glands |

| Respiratory features | Asthma, recurrent infections |

| Gastrointestinal features | Feeding difficulties, recurrent vomiting, chronic diarrhoea |

| Immune dysfunction | Depressed lymphocyte function, cellular immune hypofunction, increased susceptibility to recurrent nasal and respiratory infections. Allergic conditions as asthma, eczema, pruritus |

Systemic manifestations of HED

HED is primarily characterised by partial or complete absence of eccrine sweat glands causing lack of or diminished sweating (anhidrosis or hypohidrosis), heat intolerance and fever.2 3 The skin is dry and eczematous.

The scalp hair is sparse (hypotrichosis), fine, lightly pigmented, dry, brittle or abnormal in texture due to incomplete formation and reduced number of hair follicles.2

Teeth may be absent (anodontia), malformed or sparse (hypodontia), widely spaced, pointed and discoloured due to lack of enamel.4 Dentition may be delayed by up to 2 years.

Many individuals with HED have characteristic facial features, including a prominent forehead (frontal bossing); underdeveloped nostrils (hypoplastic alae nasi), sunken nasal bridge (saddle nose); and sunken cheeks (malar hypoplasia) or micrognathia (mandibular hypoplasia).

HED variably affects the mucous lining of gastrointestinal tract and respiratory tract. The mucous glands may be absent, reduced in number or may not function normally.

The feeding difficulties are attributed to undersecretion of saliva, hypodontia causing problems with chewing, tasting and swallowing food. Voice changes are due atrophic rhinitis, hypoplastic alae nasi, laryngeal mucous hyposecretion and vocal cord palsy.5

Growth failure may occur due to undernutrition and recurrent infections.6

It may be associated with decreased function of certain components of the immune system (eg, depressed lymphocyte function, cellular immune hypofunction), potentially causing an increased susceptibility to recurrent nasal and respiratory infections. Certain allergic conditions as asthma, eczema, pruritus are also common.

Ocular manifestations in HED

HED primarily presents with features of dry eyes, corneal vascularisation and pannus. Complications may include corneal scarring, ulcers and perforation. They are caused by the combined effect of dysplasia, tear deficiency and eye infection.

Lid abnormalities as recurrent inflammation of lid margins, trichiasis and loss of eyelashes and eyebrows are also present. Meibomian glands may be absent or have missing orifices and secretions.7

The corneal changes and meibomian gland deformities have been described in a subtype of ED called ‘EEC syndrome’.8 EEC syndrome may also be associated with atresia of nasolacrimal duct system.9 Kaercher10 has done extensive work on determining the alteration of meibomian glands by technique of transillumination (meibomianoscopy) in patients with ED syndromes. His investigations have identified partial loss of glands, coarsening of acini and complete absence of meibomian glands distributed symmetrically in lids.

Management

A multidisciplinary team is required for management of HED and normal development of child. An individual affected by HED is prone to hyperthermia hence advised to maintain cool surrounding temperature with air conditioning, light clothing, plenty of fluids and avoiding direct sunlight. Topical emmolients are required for dry eczematous skin and dermatological consultation for infective and allergic skin conditions. Alopecia can be managed by using wigs for cosmesis.

The dental anomalies in HED starts at an early age and a paediatric dentist plays a major role in dental evaluation and treatment at various stages of development. The child may need dentures and dental implants with frequent replacement as child grows.11

The feeding difficulties due to maldevelopment of teeth and malabsorption due to mucosal inflammation may affect the growth of child. This would require prompt evaluation by gastroenterologist and a dietician for nutritional advice.

Speech and language therapist, otolaryngologist and respiratory physician plays a major role in vocal development and treatment of chronic respiratory conditions.

Other members of the family must be examined for signs of this syndrome and offered genetic counselling.

The ocular features in ED may range from mild to sight threatening symptoms. Early diagnosis and treatment is recommended. The treatment may range from use of lubricants for treatment of dry eyes to surgical management of its complications. The purpose of this case report is to increase awareness of this disorder among ophthalmologists as a part of multidisciplinary team.

Learning points.

-

▶

HEDs is a group of rare multisystemic genetic syndromes that affects ectodermal structures such as skin, hair, nails, teeth and sweat glands.

-

▶

The ocular features in ED may range from mild to vision threatening symptoms. Early diagnosis and treatment is recommended.

-

▶

A multidisciplinary approach is required for management of systemic diseases.

-

▶

Genetic evaluation of affected individuals and carriers and genetic counselling may play a role in predicting disease in future progeny.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs Joanne Carmichael and Mr Liam Carmichael (medical photographers) and medical illustration department of Rotherham General Hospital.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Wright JT, Grange DK, Richter MK. Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. In: Pagon RA, Bird TC, Dolan CR, et al. (eds). GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993–2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouse C, Siegfried E, Breer W, et al. Hair and sweat glands in families with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: further characterization. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:850–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg D, Weingold DH, Abson KG, et al. Sweating in ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. A review. Arch Dermatol 1990;126:1075–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clauss F, Manière MC, Obry F, et al. Dento-craniofacial phenotypes and underlying molecular mechanisms in hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED): a review. J Dent Res 2008;87:1089–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel E, McCurdy EA, Shashi V, et al. Ectodermal dysplasia: otolaryngologic manifestations and management. Laryngoscope 2002;112:962–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motil KJ, Fete TJ, Fraley JK, et al. Growth characteristics of children with ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. Pediatrics 2005;116:e229–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mondino BJ, Bath PE, Foos RY, et al. Absent meibomian glands in the ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, cleft lip-palate syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1984;97:496–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mawhorter LG, Ruttum MS, Koenig SB. Keratopathy in a family with the ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting syndrome. Ophthalmology 1985;92:1427–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Käsmann B, Ruprecht KW. Ocular manifestations in a father and son with EEC syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1997;235:512–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaercher T. Ocular symptoms and signs in patients with ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004;242:495–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhanrajani PJ, Jiffry AO. Management of ectodermal dysplasia: a literature review. Dent Update 1998;25:73–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]