Abstract

Our case report pertains to a 32-year-old woman initially presenting with left flank pain and gross haematuria throughout her urinary stream. CT of her kidney/ureter/bladder (CT KUB) revealed ureteric dilatation to the level of the bladder without evidence of renal calculus and subsequently a stent was inserted. She represented a month later with contralateral flank pain, and a transuretheral resection of bladder tumour was performed. Histopathological diagnosis was epithelioid angiosarcoma. Further imaging (MRI pelvis) revealed that the tumour arose from the posterior bladder wall with local invasion and regional lymph node metastasis. Ifosfamide and epirubicin chemotherapy with single-fraction radiotherapy induced significant reduction in tumour bulk, although this initial response was followed by the development of symptoms suggestive of disease progression. She died 19 months after initial diagnosis with persistent pulmonary and vertebral metastases although no autopsy was performed.

Background

Primary bladder angiosarcoma is an extremely rare malignancy that has not been well characterised in the literature. This case reports the first female patient to have true primary angiosarcoma affecting the bladder. Additionally, reliance of positive keratin staining on histopathology may lead to the false diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinoma in place of angiosarcoma.

Case presentation

Presenting symptoms were gross haematuria and left-sided flank pain. She was 32 years old and 6 months postpartum with her third child. Previous medical history was unremarkable, she was a non-smoker, she did not drink alcohol and there was no known exposure to vinyl chloride, thorium contrast or arsenic.

Investigations

Ultrasound at initial presentation revealed marked left renal pelvicalyceal dilatation with further hydroureter to the level of the ureteric orifice seen on CT abdomen. A small section of bladder tissue taken during subsequent cystoscopy underwent histopathological assessment, which reported malignant atypical cells, some of which contained large, hyperchromatic nuclei and mitotic figures. These features were not considered diagnostic.

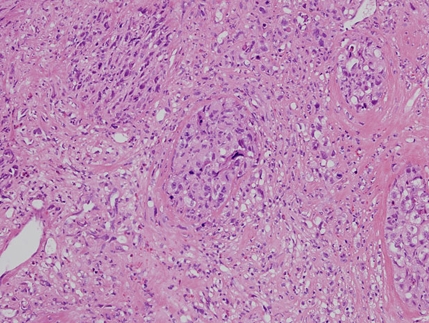

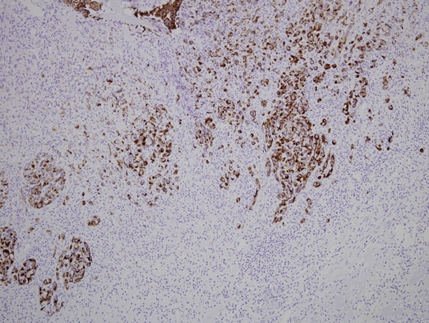

One month later, transurethral resection near the right ureteric orifice was performed. Nine pieces measuring 25×15×4 mm in totality were evaluated. In most areas, the tumour cells were arranged in nests and cors but some lined vascular channels (figure 1). In several sections, tumour cells contained abundant cytoplasm, occasionally associated with intracellular lumina containing erythrocytes. The tumour cells showed large, irregular nuclei and many had an epithelioid morphology. Numerous mitotic figures including atypical mitoses were seen. The overlying urothelium appeared reactive and hyperplastic. The tumour was concentrated in the lamina propria of the bladder and extended deeply into the detrusor muscle. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD31, fVIII-related antigen, ULEX and CD34, consistent with angiosarcoma. The cells also stained positively for cytokeratins: AE1/AE3 (moderate), Cam5.2 (CK8) (moderate) and MNF116 (strongly positive, figure 2). CK20 and ethidium monoazide bromide stains proved negative.

Figure 1.

Malignant epithelioid cells arranged in nests. H&E stain, objective magnification ×20.

Figure 2.

Nests of malignant cells stained strongly positive for pancytokeratin MNF116, objective magnification ×20.

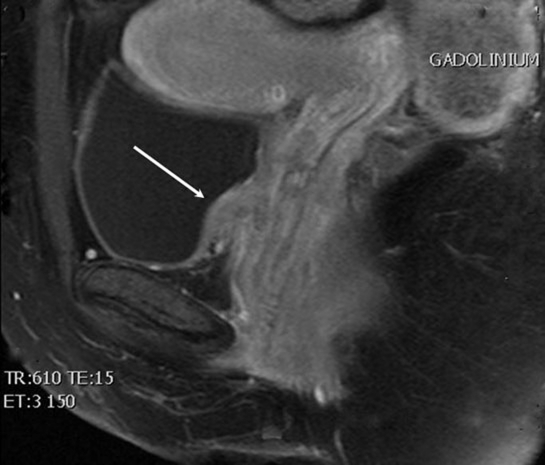

Pelvic MRI demonstrated the presence of a bladder wall nodule 12 mm anteroposterior and 9 mm craniocaudal in size (figure 3). Left superficial inguinal lymph nodes appeared enlarged with the largest measuring 18×10 mm. A left-sided obturator lymph node measured 15×10 mm.

Figure 3.

Immediate postcontrast (gadolinium) T1-weighted fat-saturated MRI of the pelvis revealing bladder mass invading the anterior vaginal wall (arrow).

Prior to chemotherapy, staging CT chest and abdomen revealed a 41×62×48 mm pelvic mass involving the posterior bladder wall, enlargement of a para-aortic lymph node left of the aorta (10 mm) and an enlarged left external iliac lymph node (10 mm). No evidence of metastatic involvement of the lungs, liver or skeletal elements was identified. After four cycles of chemotherapy, progress CT revealed a significant interval reduction in the size of the pelvic mass (48×27×32 mm) and reduction of the left para-aortic (4 mm) and left external iliac (5 mm) nodes.

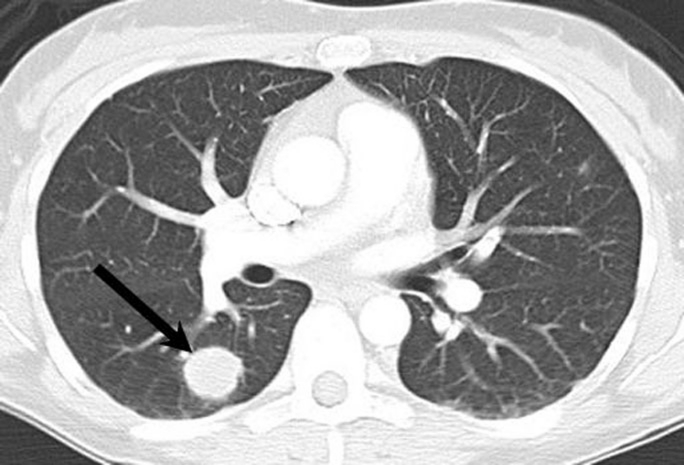

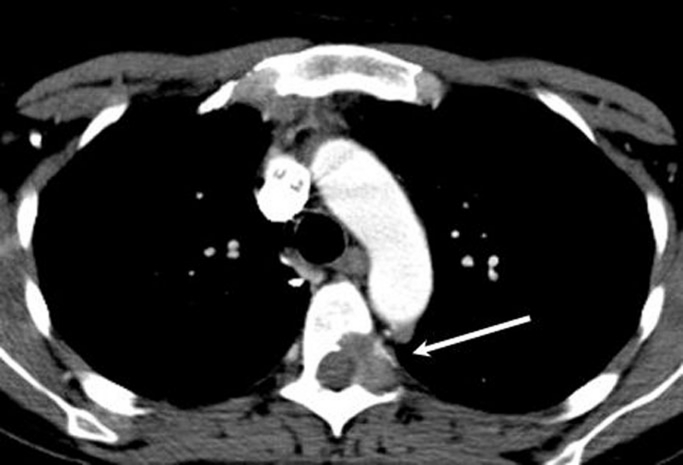

Over the next 9 months, our patient developed symptoms suggestive of local disease progression, which was reflected by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography (PET). She also developed metastatic disease in the lower lobe of the right lung (figure 4) and in the left pedicle of T5 as seen on CT (figure 5). Further PET scans revealed a partial response to paclitaxel chemotherapy.

Figure 4.

CT chest showing metastatic pulmonary lesion in the lower lobe of right lung (arrow).

Figure 5.

CT chest showing a metastatic lytic lesion in the left pedicle of T5 (arrow).

Differential diagnosis

The most common primary bladder tumour is the transitional cell carcinoma, accounting for 90% of bladder cancer. Of these, 60% exhibit focal squamous differentiation with intracellular keratin.1 In our case, the presence of endothelial markers and primitive intracytoplasmic vasculature with erythrocytes is indicative of angiosarcoma despite positive staining for cytokeratins.2 Pelvic MRI confirmed the bladder as the primary organ involved. Other differentials include metastases to the bladder, possible primary lesions including melanoma and carcinoma of the stomach, breast and lung as well as contiguous spread from the female genital tract.2

Treatment

Due to the extension of disease up to the para-aortic lymph nodes, curative surgery was not possible. She was therefore referred for palliative chemoradiotherapy – six cycles of ifosfamide and epirubicin with single-fraction radiotherapy (4 Gy) for haematuria and per vaginal blood loss.

On re-presentation with persistent pelvic pain and polycythaemia vera (PV) blood loss after chemoradiotherapy, she was treated with 10 cycles of pelvic radiotherapy (3 Gy), fentanyl patches, methadone, pregabalin and paracetamol.

The discovery of metastatic pulmonary lesions necessitated further chemotherapy, and weekly paclitaxel was selected given recent evidence of clinical benefit in systemic angiosarcoma.3

Outcome and follow-up

There was significant symptomatic improvement and reduction in tumour size after six cycles of ifosfamide and epirubicin. Local and metastatic progression manifested over a 9-month period as persistent pelvic pain, PV blood loss and development of pulmonary and vertebral lesions. Paclitaxel appeared to limit disease progression to a visible extent as seen on progress PET scans. She died approximately 19 months after the diagnosis of angiosarcoma was made. No autopsy was performed.

Discussion

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare and represent less than 1% of all cancers. Angiosarcoma constitutes 2% of these soft tissue sarcomas.4 They can occur in any region of the body, although more than 50% arise in the head and neck.5

A literature search using PubMed revealed 15 cases of angiosarcoma affecting the bladder, with the present case being the sixteenth.2 6–20 All cases are summarised in Tables 1–3. Of these 16 cases, six cases involved prior exposure to abdominopelvic radiotherapy,10–13 17 20 one case initially presented with a cutaneous manifestation of angiosarcoma,19 one case appeared to be a variant of Kaposi’s sarcoma16 and two cases arose from haemangiomas,7 9 leaving five previous cases to be true primary bladder angiosarcomas with the current case being the sixth.2 6 8 14 15 18 With the inclusion of the current case, the mean age at diagnosis of true primary bladder angiosarcoma (excluding those mentioned above) is 54.5 (range 32–78). Haematuria was the presenting feature in all but one case. Five of the six cases of primary angiosarcoma arose in male patients. Metastatic extension to at least regional lymph nodes was documented in four of the six cases. All cases except the present case incorporated surgical management, with cystoprostatectomy in three cases and partial cystectomy in two cases. Transuretheral resection of bladder tumour was performed in the current case. Chemotherapy was utilised in two cases and radiotherapy was used in three cases. In four cases with documented outcomes, the length of survival after diagnosis was highly variable (mean 20.75 months, range 2–54). Chemoradiotherapy appeared to increase the length of survival (36.5 months vs 5 months without chemoradiotherapy). Greater survival has been documented in patients with angiosarcoma who undergo adjuvant radiotherapy while the benefit of chemotherapy is somewhat unclear.4

Table 1.

Primary status, age, sex and clinical presentation of angiosarcomas arising in the bladder

| Case and authors | Primary/associated with RFs | Age/sex and clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Jungano9 | Arose from haemangioma | 54/M – obstruction and intermittent haematuria |

| Casal et al7 | Arose from haemangioma | 85/F – haematuria, dysuria and weight loss |

| Wasmer et al19 | Initial cutaneous presentation, 6/12 later haematuria | 61/M – haematuria, diminished stream and hesitancy |

| Schwartz et al16 | ?variant of Kaposi’s sarcoma – cutaneous lesions | 46/M – painless full-stream haematuria |

| Stroup and Chang18 | Primary | 68/M – gross haematuria with clots |

| Nanus et al12 | Adjuvant radiotherapy 16 years prior for ovarian dysgerminoma | 47/F – obstruction |

| Angiosarcoma initially presented in ileum, labium | ||

| Morgan et al11 | Had intraperitoneal radium 9 years prior for endometrial adenocarcinoma | 72/F – intermittent painless vaginal bleeding and haematuria |

| Aragona et al6 | Primary | 78/M – dysuria, gross haematuria |

| Ravi15 | Primary | 55/M – intermittent painless haematuria |

| Navon et al13 | Radiotherapy 13 years prior for prostate cancer | 78/M – single episode of gross haematuria |

| Engel et al,8 Pazona et al14 | Primary | 47/M – intermittent haematuria with suprapubic and left flank pain |

| Schindler et al2 | Primary | 47/M – dysuria, left flank pain |

| Seethala et al17 | Radiation 4 years prior | 66/M – painless haematuria |

| Kulaga et al10 | External beam irradiation 14 years prior for endometrial adenocarcinoma | 83/F – painless microhaematuria |

| Williams et al20 | External beam therapy for prostate cancer 10 years prior | 71/M – single episode gross painless haematuria |

| Current case | Primary | 32/F – gross haematuria with left flank pain |

F, female; M, male; RF, renal failure.

Table 3.

Treatment and outcome of primary bladder angiosarcomas

| Case | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Stroup and Chang18 | Partial cystectomy, later followed by radical cystoprostatectomy | Local recurrence 5 months after initial excision. Patient died 8 months after diagnosis – metastases seen in liver and lungs |

| Aragona et al6 | Partial cystectomy (diverticulectomy) | Patient died 2 months after diagnosis. No autopsy although apparently tumour-free |

| Ravi15 | Partial cystectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy (5500 Gy to pelvis) | No evidence of recurrence at 8 months |

| Engel et al,8 Pazona et al14 | Radical cystectomy with ileal conduit | Metastasis to right groin lymph nodes. No evidence of recurrence at 32 months after diagnosis. Patient died 6 years after diagnosis with no evidence of recurrence at autopsy |

| Five cycles of MAID chemotherapy with radiotherapy (6420 cGy to right groin) | ||

| Schindler et al2 | Radical cystoprostatectomy | Metastatic involvement of right inguinal lymph nodes. Outcome not disclosed. |

| Current case | TURBT + 6 cycles of ifosfamide + epirubicin + single-fraction radiotherapy (4 Gy) for PV bleeding. Later received 10 cycles of radiotherapy for persistent PV bleeding and weekly paclitaxel for metastatic disease. | Regional lymph node metastases up to aortic bifurcation. Reduction in tumour bulk after six cycles of chemoradiotherapy. Progression of disease 3 months later with pelvic pain, worsening PV bleeding and lung metastases. Patient died 19 months after diagnosis. No autopsy performed. |

MAID, modified mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide and dacarbazine; PV, polycythaemia vera; TURBT, transuretheral resection of bladder tumour.

Table 2.

Features of primary bladder angiosarcomas

| Case | Architecture and cell morphology | Immunohistochemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Stroup and Chang18 | Complex anastomosing, blood-filled vascular sinuses. Pleomorphic endothelial cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei, ‘hobnail’ cells surrounding lumina | fVIII+, keratins− |

| Aragona et al6 | Classic – anastomosing blood-filled channels | fVIII+, cytokeratins−, desmin−, myoglobin−, vimentin−, S100−, Leu-7− |

| Typical and spindled cell types seen | ||

| Ravi15 | Classic – anastomosing blood-filled channels | * |

| Typical – hyperchromatic nuclei, ‘hobnail’ | ||

| Engel et al,8 Pazona et al14 | Classic – anastomosing blood-filled channels lined by tumour cells | CD31+ |

| Epithelioid cell type | ||

| Schindler et al2 | Clumped tumour cells, no vascular lumen formation or intracytoplasmic lumen formation, no erythrocytes | Vimentin+, CD31+, CD34−, cytokeratins AE1/3−, fVIII− |

| Epithelioid cell type | ||

| Current case | Most cells are arranged in nests and cors, but some are seen to line vascular formations. Some tumour cells contain intracytoplasmic lumen formation with erythrocytes. In most areas, the cells are of epithelioid morphology, with focal areas of spindled cell types | CD31+ fVIII+, CD34+, pancytokeratins AE3+, MNF116+, Cam5.2+ |

Immunohistochemistry was not reported.

Histologically, four of the six cases6 8 15 18 resembled a ‘classical’ architecture17 21 with anastomosing blood-filled channels lined by malignant cells. One of the cases resembled a ‘solid’ architecture,2 with malignant cells forming sheets or nests in the absence of evidence of lumen formation. The present case incorporated both classical and solid architectural features. In two cases,15 18 the tumours were ‘typical’ in morphology, with hyperchromatic, ‘hobnail’ endothelial cells.17 21 In one case, both typical and ‘spindled’ (fusiform or tapered edges) cells were seen.6 In the remaining three cases, epithelioid cell morphology (prominent nucleoli, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm) was seen.

Immunohistochemical staining varied between the five cases reporting relevant results from staining and no single marker was positive in all cases. fVIII-related antigen, CD31, CD34 and vimentin were commonly tested. The present case demonstrated positivity for cytokeratins, including AE1/3, CAM5.2 and MNF116. It is recognised that epithelioid angiosarcomas may stain positively for keratin markers22 and reliance on these stains may lead to misdiagnosis. In the presence of vascular features and positivity of vascular markers, CD31 and CD34 would indicate angiosarcoma.

Learning points.

-

▶

Angiosarcoma of the bladder is an exceedingly rare but aggressive malignancy that most commonly presents with haematuria.

-

▶

A multimodal approach, including chemoradiotherapy, appears to maximise the length of survival after diagnosis.

-

▶

Reliance on positive cytokeratin staining can lead to the false diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinomas as epithelioid angiosarcomas can also stain positively for cytokeratins.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr James Anderson (Department of Radiology, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Western Australia) and Dr Jenny Ho (Central City Medical Centre, Perth, Western Australia) for their help.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Jacobs BL, Lee CT, Montie JE. Bladder cancer in 2010: how far have we come? CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:244–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schindler S, De Frias DV, Yu GH. Primary angiosarcoma of the bladder: cytomorphology and differential diagnosis. Cytopathology 1999;10:137–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX Study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5269–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark RJ, Poen JC, Tran LM, et al. Angiosarcoma. A report of 67 patients and a review of the literature. Cancer 1996;77:2400–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JC, Rosenberg SA, Glastein EJ, et al. Sarcomas of soft tissue. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Fourth edition Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1993:1436–55 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aragona F, Ostardo E, Prayer-Galetti T, et al. Angiosarcoma of the bladder: a case report with regard to histologic and immunohistochemical findings. Eur Urol 1991;20:161–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casal J, Singer ED, Monserrat JM. Angiosarcoma of the bladder (Spanish). Rev Argent Urol Nefrol 1970;39:53–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel JD, Kuzel TM, Moceanu MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the bladder: a review. Urology 1998;52:778–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jungano F. Sur un cas d’angio-sarcome de la vessie. Annales des maladies des organs genitourinarie 1907;25:1451–61 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulaga A, Yilmaz A, Wilkin RP, et al. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the bladder after irradiation for endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Virchows Arch 2007;450:245–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan MA, Moutos DM, Pippitt CH, Jr, et al. Vaginal and bladder angiosarcoma after therapeutic irradiation. South Med J 1989;82:1434–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanus DM, Kelsen D, Clark DG. Radiation-induced angiosarcoma. Cancer 1987;60:777–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navon JD, Rahimzadeh M, Wong AK, et al. Angiosarcoma of the bladder after therapeutic irradiation for prostate cancer. J Urol 1997;157:1359–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pazona JF, Gupta R, Wysock J, et al. Angiosarcoma of bladder: long-term survival after multimodal therapy. Urology 2007;69:575, e9–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravi R. Primary angiosarcoma of the urinary bladder. Arch Esp Urol 1993;46:351–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz RA, Kardashian JF, McNutt NS, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma resembling anaplastic Kaposi’s sarcoma in a homosexual man. Cancer 1983;51:721–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seethala RR, Gomez JA, Vakar-Lopez F. Primary angiosarcoma of the bladder. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1543–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stroup RM, Chang YC. Angiosarcoma of the bladder: a case report. J Urol 1987;137:984–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasmer JM, Block NL, Politano VA, et al. Penile angiosarcoma presenting in the bladder. Urology 1981;51:721–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams S, Romaguera R, Kava B. Angiosarcoma of the bladder: case report and review of the literature. Scientific World Journal 2008;8:508–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Angiosarcoma of soft tissue: a study of 80 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:683–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. Fifth edition St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2008 [Google Scholar]