Abstract

Control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a huge challenge of global medical importance. Using a variety of in vitro approaches neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) have been identified in patients with acute and chronic hepatitis C. The exact role these nAbs play in the resolution of acute HCV infection still remains elusive. We have previously shown that purified polyclonal antibodies isolated from plasma obtained in 2003 from a chronic HCV patient (Patient H) can protect human liver chimeric mice from a subsequent challenge with the autologous HCV strain isolated from Patient H in 1977 (H77).

In this study we investigated whether polyclonal antibodies isolated from patient H in 2006 (H06), which display high cross-genotype neutralizing activity in both the HCVpp and HCVcc systems, were also able to prevent HCV infection of different genotypes (gt). Following passive immunization with H06-antibodies, chimeric mice were challenged with the consensus strains H77C (gt1a), ED43 (gt4a) or HK6a (gt6a). In accordance with previous results, H06-antibodies prevented infection of chimeric mice with the autologous virus. However, the outcome of a homologous challenge is highly influenced by the amount of challenge virus injected. Depending on the viral genotype used, H06-antibodies were able to protect up to 50% of chimeric mice from a heterologous challenge. Animals in which the antibody pretreatment failed, displayed a clear delay in the kinetics of viral infection. Sequence analysis of the recovered viruses did not suggest antibody-induced viral escape.

Conclusion

Polyclonal anti-HCV antibodies isolated from a chronic HCV patient can protect against an in vivo challenge with different HCV genotypes. However, the in vivo protective efficacy of cross-genotype neutralizing antibodies was less than predicted by cell culture experiments.

Keywords: Chimeric mice, uPA-SCID, passive immunization, HCV

Introduction

It is estimated that about 15–25% of patients suffering from an acute HCV infection spontaneously clear the virus within six months, while 75–85% of cases evolve towards chronicity. The natural course and outcome of the infection are considered to be determined by both viral and host characteristics. The factors determining spontaneous clearance have not yet been fully defined, but it is widely accepted that the initiation of a strong innate as well as a broad and vigorous adaptive cellular immune response, early after infection, contributes to control and clearance of the virus during the acute phase of infection (reviewed by Dustin and Rice in (1)). Which role, if any, the humoral immune response plays in the spontaneous resolution of HCV infection remains an enigma. Using retroviral pseudoparticles that contain the HCV envelope proteins (HCVpp) (2, 3) several investigators have revealed in the plasma of chronically infected patients (4, 5) the presence of antibodies with neutralizing capacity (nAbs) displaying broad reactivity against different genotypes (6). While Bartosch et al. could not detect nAbs in sera from patients with spontaneously-resolving HCV infection (4), Logvinoff et al. reported the presence of nAbs in the acute phase of a minority of patients, albeit without any correlation with viral clearance (5).

Increasing evidence supports the role of nAbs in viral protection and disease outcome. First, HCV patients suffering from agammaglobulinemia experience an accelerated disease progression (7). Second, HCV-contaminated commercial immunoglobulin preparations derived from anti-HCV-screened plasma transmitted HCV after intravenous administration, while preparations made from unscreened plasma did not. Further analysis showed that the latter preparations contained HCV-specific nAbs (8). Pestka et al. showed that in a cohort of accidentally exposed patients, nAbs with broad reactivity were rapidly induced only in those patients that were able to spontaneously clear the virus (9). After recovery these antibodies decreased or even disappeared. In contrast, nAbs were absent or barely detectable in acute phase plasma of patients that ultimately evolved to chronicity (9). More recently, a longitudinal analysis of six HCV-infected patients undergoing liver transplantation showed that HCV variants that re-infected the liver graft were only poorly neutralized by antibodies present in pre-transplant plasma, while the viral variants that could no longer be detected following transplantation were efficiently neutralized (10).

Using the HCVpp-system and also the more recently developed infectious cell culture system (HCVcc) (11–13) antibodies that can neutralize HCV of different genotypes have been identified (6, 14, 15). However, because the characteristics of HCVpp and HCVcc differ from that of plasma-derived virus, we have recently evaluated the capacity of polyclonal antibodies isolated from the plasma obtained in 2003 (plasma H03) from a chronic HCV-infected patient (Patient H) to protect “human liver-chimeric mice” from a challenge with the autologous HCV strain (H77C) that originally infected this patient in 1977 (16). We showed that passive immunization of chimeric mice prevented the majority of challenged mice from infection while those that did become infected showed a significant delay in the kinetics of the infection (16).

Using the same humanized mouse model we have now evaluated the cross-genotype neutralizing capacity of polyclonal antibodies isolated from the same patient in 2006 (H06) and have compared their ability to neutralize heterologous virus in vivo with in vitro neutralization data (14, 15).

Materials and Methods

Generation of chimeric mice

Human liver-uPA-SCID mice were produced essentially as described before (17). Briefly, homozygous uPA+/+-SCID mice (18) were transplanted within two weeks after birth with approximately 106 cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium). All animals used in this study were transplanted with hepatocytes from a single donor. Several weeks after transplantation, human albumin was quantified in mouse plasma with an in-house ELISA (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX). Only animals containing more than 1 mg/ml of human albumin in their plasma were considered as successfully engrafted. The study protocol was approved by the animal ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Ghent University.

Viral inoculum and polyclonal antibodies

All chimeric mice were loaded with 1 mg/g body weight of purified polyclonal Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies isolated from patient H plasma collected in 2006 (H06) or with purified control immunoglobulins isolated from HCV-negative healthy volunteers. IgG were purified according to a previously described method (19) with some modifications. Briefly, the plasma was first delipidated with fumed silica (Sigma-Aldrich), treated with 1% Tri-N-butyl phosphate and 1% Triton X-100 at 25°C for 6 hours with constant shaking to inactivate the virus, and followed by fractionation on anionic Q Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), and removing detergent by absorbing the IgG on cationic SP Sepharose column (GE Healthcare). The purified IgG was finally formulated with glycine, pH 5.2, at protein concentration of 50 mg/ml. This 5% IgG solution was further incubated at 22°C–26°C for 21 days before being stored at 5°C and used for the animal experiment. A total of 4 g purified IgG was obtained from 400 ml of patient H plasma.

Three days after infusion of the antibodies, the animals were injected with a 100% infectious dose of the following HCV strains: mH77C (genotype 1a, autologous virus), mED43 (genotype 4a) or mHK6a (genotype 6a). The challenge viruses mH77C, mED43 and mHK6a were produced by infecting different naïve chimeric mice (hence the prefix “m”) with a pool of acute phase plasma derived from chimpanzees infected with H77C, ED43 and HK6a, respectively (20). Both the antibody and the virus were injected intraperitoneally. We have previously shown that 3 days after injection only a minimal amount of antibody is retained in the peritoneal cavity (16).

HCV RNA detection and quantification

After bleeding, plasma was prepared and stored at −80°C until further analysis. HCV RNA was quantified using the Roche COBAS Ampliprep – COBAS TaqMan HCV test (Roche Diagnostics, Vilvoorde, Belgium), which has a lower limit of detection of 15 IU/ml. However, due to the limited amounts of plasma available, samples had to be diluted. Depending on the dilution, the detection limit ranged from 150 IU/ml to 1,500 IU/ml.

Amplification and sequence analysis of HCV envelope region

The sequence of the E1E2-region of all H06-treated mice that became HCV-positive was analyzed and compared to the viral sequence of untreated control mice. First, total RNA was purified from mouse plasma using the ZR Viral RNA kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). cDNA was synthesized using superscript III reverse transcriptase in combination with random primers (Invitrogen, Merelbeke, Belgium). Nested PCR was used to amplify the E1E2-region using LongAmp Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The primers used for amplification of ED43 envelope region were 5′-TGGGCAGGATGGCTCTTGTC-3′ (F), 5′-CCCTAGCCAGCCATAACTTG-3′ (R), 5′-TCGCCGACCTCATGGGATAC-3′ (nested F) and 5′-CAGCGGCTGAAGCAGCATTG-3′ (nested R). The primers used for amplifying the HK6a envelope region were 5′-CCCGGAATTTGGGTAAGGTC-3′ (F), 5′-AAGGCACCTTGAGCAAACTG-3′ (R), 5′-CTACTCTCGTGCCTCACAAC-3′ (nested F) and 5′-GCCGCATTGAGGACGACAAG-3′ (nested R). All PCR products were gel-eluted and sequenced (GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany). The numbering used to identify the mutations in the mED43 viral sequence refers to the ED43 consensus sequence published in GenBank (accession number GU814265) (21). The envelope sequence of the virus in mHK6a-infected mice was compared to the sequence of chimeric HK6a/JFH1 virus (GenBank accession number FJ230883) (15). However, since the full-length sequence of the HK6a genome has not been published yet, our numbering refers to the published H77 sequence (GenBank accession number AF009606).

Results

Homologous in vivo neutralization

To validate the new batch of polyclonal antibodies (H06), its capacity to neutralize the autologous H77C strain was compared to that of a preparation obtained from the same patient in 2003 (H03) (16). Therefore we injected 1 mg of purified H06-IgG per gram body weight into three uPA+/+-SCID mice that harbored human hepatocytes in their liver (chimeric mice) on day 0 and challenged them with H77C virus on day 3. Previous experiments had demonstrated that this was the optimal dose and schedule for nAb to achieve protection (16). The viral challenge with 104 IU of mH77C per mouse is sufficient to induce a robust infection in all tested control animals (16, 22). The HCV RNA titers in two untreated control mice during week 1–4 post-challenge are shown in Table 1. A weekly follow-up of the viral RNA levels in the plasma of three chimeric mice loaded with H06-IgG showed that two weeks after injection of the mH77C virus all animals remained HCV negative (< 1,500 IU/ml) (Table 1 and Figure 1). Between the second and third week two animals died spontaneously, but the remaining third mouse remained HCV negative until week 5 (< 750 IU/ml), after which this animal also died spontaneously.

Table 1.

Plasma analysis of HCV-challenged chimeric mice passively immunized with irrelevant or H06 antibodies.

| HCV strain | IgG | dosec (IU/mouse) | Mouse ID | HCV RNA (log10 IU/mL) |

outcome |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 8 | # protected | ||||

| mH77C | irr.a | 104 | K302 (°21/5/06) | 4,39 | 7,12 | 7,58 | 6,89 | 0/2 | |||

| K302R (°22/5/06) | 3,41 | 6,55 | 7,69 | 7,49 | |||||||

| H06b | 104 | K690R (°18/11/07) | <3,18 | <3,18 | animal died | 3/3 | |||||

| K672R (°20/11/07) | <3,18 | <3,18 | <3,18 | <2,88 | animal died | ||||||

| K643 (°19/11/07) | <3,18 | <3,18 | animal died | ||||||||

| H06 | 105 | K629 (°16/08/07) | <3,18 | 5,36 | 7,38 | 7,12 | 1/3 | ||||

| K629R (°16/08/07) | <3,18 | 4,89 | 6,54 | 6,81 | |||||||

| K529 (°23/08/07) | <3,18 | <3,18 | <3,18 | <3,18 | <2,88 | <2,78 | |||||

| mED43 | irr. | 104 | K663L (°24/04/08) | 5,89 | 6,68 | 6,25 | 0/3 | ||||

| K619 (°20/08/07) | 7,68 | 7,58 | 7,88 | 7,45 | |||||||

| K619R (°20/08/07) | 5,34 | 6,92 | 6,78 | ||||||||

| H06 | 104 | K676 (°18/11/2007) | <3,18 | 3,32 | 5,63 | 6,92 | 1/6 | ||||

| K627 (°14/02/08) | <3,18 | <3,18 | <3,18 | <2,88 | <2,88 | <2,88 | |||||

| K818 (°10/09/08) | <2,88 | 5,87 | 7,10 | animal died | |||||||

| K528 (°15/08/07) | <3,18 | 3,75 | 7,16 | 7,19 | |||||||

| K614 (°12/08/07) | <3,18 | <3,18 | 3,24 | <3,18 | 3,12 | ||||||

| K606R (°21/08/07) | <3,18 | 7,63 | 7,52 | 7,54 | |||||||

| mHK-6a | irr. | 105 | K811 (°09/09/2008 | 4,90 | 6,64 | 7,13 | 6,36 | 0/3 | |||

| K811R (°09/09/2008) | 4,82 | 6,81 | 7,52 | 7,31 | |||||||

| K811L (°09/09/2008) | 4,73 | 6,66 | 7,05 | 6,67 | |||||||

| H06 | 105 | K800 (°11/09/08) | <2,57 | <2,57 | animal died | 2/4 | |||||

| K800RL (°11/09/08) | 4,66 | 5,11 | animal died | ||||||||

| K809L (°09/10/08) | <2,57 | <2,57 | <2,57 | <2,57 | |||||||

| K787 (°23/10/08) | <2,57 | 4,42 | 5,80 | ||||||||

irr.: irrelevant human IgG

H06: IgG isolated in 2006 from patient H

dose: minimal dose injected in each animal to achieve infection in all challenged chimeric mice

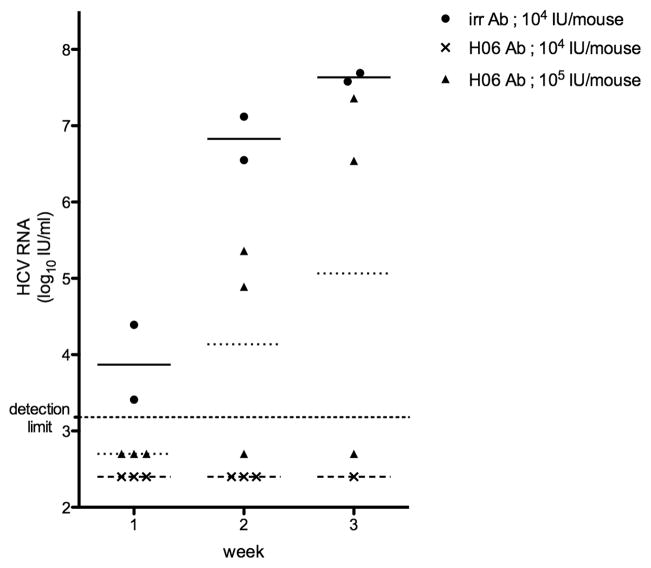

Figure 1. viral load in treated and non-treated chimeric mice challenged with HCV of genotype 1a strain mH77C.

Chimeric mice were injected with either irrelevant control IgG (➂) or H06-antibodies (➉ and ▭). Three days later all animals were infected with 104 IU/mouse (➂ and ▭) or 105 IU/mouse (➉) of mH77C. HCV RNA (IU/ml) present in plasma was quantified weekly and all individual levels are shown. Horizontal lines represent the geometric mean within the group (–––––: control challenge group; ------: H06-treated low dose HCV challenge group; ........: H06-treated high dose HCV challenge group).

To further evaluate the potency of H06-antibodies in neutralizing the autologous virus, we challenged three chimeric mice, pretreated with H06-IgG as described above, with a 10-fold higher dose of the mH77C virus (105 IU/mouse). As shown in Table 1, all three animals tested HCV RNA negative (< 1,500 IU/ml) one week after injection of the virus. However, one week later two animals scored HCV RNA positive. Viremia in both these animals progressively increased until week 3, reaching levels comparable to non-treated control mice. The third animal remained negative (< 600 IU/ml) throughout the 6-week observation period. Although the H06-antibody pretreatment could not protect two out of three chimeric mice from being infected by a 10-fold higher viral challenge, in the weeks that followed the viral titers rose much slower that in untreated mice (Figure 1).

Heterologous in vivo neutralization

After validation of the polyclonal anti-HCV antibodies obtained from patient H in 2006, we investigated whether passive immunization with H06-antibodies could protect chimeric mice from a challenge with HCV strains other than the autologous H77C. In vitro studies had indicated that H06-antibodies could efficiently neutralize chimeric HCVcc containing the envelope proteins of the strains ED43 (gt4a), SA13 (gt5a), HK6a (gt6a) and QC69 (gt7a) (14, 15).

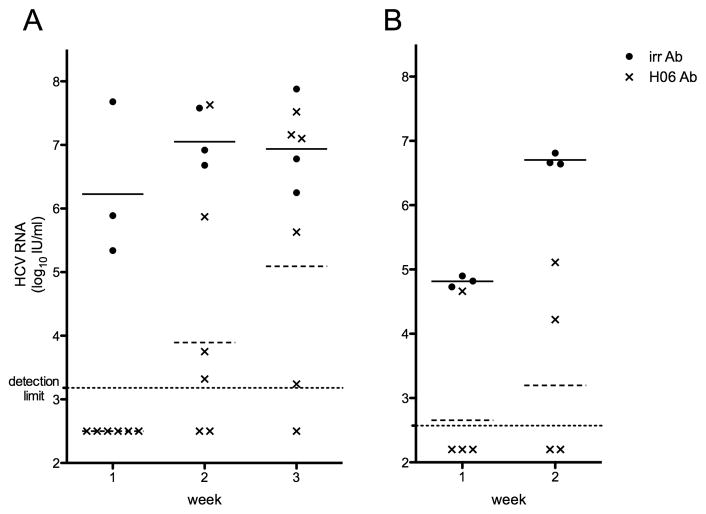

We passively immunized six chimeric mice with 1 mg/g H06-antibody and three days later challenged them with a 100% infectious dose of plasma-derived mED43 (104 IU/mouse). Three additional chimeric mice received the same viral dose but were injected with irrelevant antibody and served as a control group. One week after viral inoculation, all three control animals had plasma HCV RNA levels ranging between 2.18×105 and 4.80×107 IU/ml (Table 1). In contrast, all antibody-treated animals remained HCV negative (<1,500 IU/ml). One week later, HCV RNA could be quantified in four chimeric mice with levels ranging between 2.08×103 and 4.25×107 IU/ml. At week 3, one of the animals that was negative at weeks 1 and 2 developed low titered viremia (Figure 2a). Overall only one of six mice seemed to be completely protected from a heterologous mED43 challenge, but in the five infected animals the rise in viral titer was clearly delayed (Table 1).

Figure 2. viral load in treated and non-treated chimeric mice challenged with HCV of genotype 4a strain mED43 (A) or genotype 6a strain mHK6a (B).

Chimeric mice were injected with either irrelevant control IgG (➂) or H06-antibodies (▭). Three days later all animals were injected with the minimal dose needed to establish a robust infection in all animals. HCV RNA (IU/ml) present in mouse plasma was quantified weekly and all individual levels are shown. Horizontal lines represent the geometric mean within the group (–––––: control challenge group; ------: H06-treated challenge group).

To investigate whether H06-antibodies were able to neutralize an in vivo infection with HCV of strain mHK6a (gt6a) we treated four animals with H06-IgG as described above and challenged these mice with mHK6a (105 IU/mouse) three days later. Three non-treated control animals had HCV RNA levels of at least 5.43×104 IU/ml in the week 1 sample, increasing up to 3.34×107 IU/ml at week 3 (Table 1). Three of the four treated animals were HCV negative after one week (< 375 IU/ml). One week later HCV RNA could be detected in a second treated chimeric mouse (Figure 2b). Three weeks after injection of the virus one of the two HCV negative animals died spontaneously but in the remaining animal HCV RNA remained undetectable throughout the 8-week observation period (< 375 IU/ml).

Sequence analysis of HCV after viral breakthrough

To investigate whether the viruses that emerged in H06-treated chimeric mice contained mutations in their genome that might result in resistance to the neutralizing antibodies we sequenced the complete E1E2-region of HCV in H06-treated mice and in control animals, and compared these sequences to that of the virus that was injected.

As shown in Table 2, three of the five H06-treated mice challenged with mED43 that were not protected did not have any coding mutations in the envelope region of the recovered viruses. Thus, the HCV infection observed in these animals clearly represented a failure of neutralization, and not virus escape from nAb. However, in one H06-treated mED43-infected mouse (K614), a coding mutation was observed in the E1 region compared to the inoculum and the consensus ED43 sequence (GU814265). A mixture of this mutation (M221L) and the wild type was also observed in one of the control animals. The virus isolated from animal K614 contained two additional mutations in E2 (S405P and K446R), while the virus isolated from animal K606R contained one amino acid mutation in E2 (N573T).

Table 2.

Viral envelope amino acid sequence analysis of viruses recovered from mED43-infected chimeric mice.

| week post infectionb | E1 | E2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H77 reference (AF009606) | amino acid positiona | 221 | 405 | 446 | 572 | |

| amino acida | L | P | K | G | ||

| ED43 patient (Y11604) | amino acid position | 221 | 405 | 446 | 573 | |

| amino acid | M | S | K | N | ||

| ED43 chimpanzee (GU814265) | amino acid position | 221 | 405 | 446 | 573 | |

| amino acid | L | S | K | N | ||

| mED43 inoculum | L | S | K | N | ||

| mED43 control mice | K663L (°24/04/08) | 1 | L | S | K | N |

| K619- (°20/08/07) | 4 | L | S | K | N | |

| K619R (°20/08/07) | 3 | M/Lc | S | K | N | |

| mED43 H06-treated mice | K676 (°18/11/2007) | 6 | L | S | K | N |

| K818- (°10/09/08) | 3 | L | S | K | N | |

| K528- (°15/08/07) | 4 | L | S | K | N | |

| K614 (°12/08/07) | 5 | M | P | R | N | |

| K606R (°21/08/07) | 4 | L | S | K | T | |

amino acid found in the reference sequence at the indicated position.

mouse plasma samples used for sequence analysis were obtained at the time point indicated.

position with a quasispecies; both variants are found at comparable levels.

The envelope amino acid sequence of the virus isolated from all mHK6a-infected control animals and the H06-treated chimeric mouse K800RL was completely conserved. Only the virus isolated from animal K787 contained one coding mutation in E2 (N448D) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Viral envelope amino acid sequence analysis of viruses recovered from mHK6a-infected chimeric mice.

| week post infectionb | E2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| H77 reference (AF009606) | amino acid positiona | 448 | |

| amino acida | N | ||

| HK6a/JFH1 reference (FJ230883) | amino acid position | 448 | |

| amino acid | N | ||

| mHK6a control mice | K811- (°09/09/2008) | 3 | N |

| K811R (°09/09/2008) | 3 | N | |

| K811L (°09/09/2008) | 3 | N | |

| mHK6a H06-treated mice | K800RL (°11/09/08) | 2 | N |

| K787 (°23/10/08) | 4 | D | |

amino acid found in the reference sequence at the indicated position.

mouse plasma samples used for sequence analysis were obtained at the time point indicated.

Discussion

Antibodies with neutralizing activity against HCV are commonly detected in patients with chronic HCV infections but have also been observed in the acute phase of infections that will be cleared spontaneously (5, 9, 23). The role these neutralizing antibodies play in disease outcome and/or progression is still poorly understood. HCVcc and HCVpp systems allow for the identification and quantification of nAbs, but these tools can only be used to study certain viral strains that are artificially produced and have different characteristics compared to viral particles that are naturally produced in infected patients. Viral particles produced in cell culture have a higher density and lower specific infectivity than viral particles isolated from infected patients, chimpanzees and chimeric mice, probably because of a lack of association with low density lipoproteins (24). This difference in composition may have a profound impact on the sensitivity of the viral particles to neutralizing antibodies. In this animal study we have investigated the sensitivity of plasma-derived HCV of strains H77C (gt1a), ED43 (gt4a) and HK6a (gt6a) to a polyclonal antibody preparation (H06) that was previously shown to efficiently neutralize in vitro-produced JFH1-based chimeric viruses containing the envelope proteins of the same consensus strains (14, 15). Here we have used the identical viral strains (20) and the same antibody preparation to compare in vivo and in vitro neutralization.

As an animal model we utilized chimeric uPA+/+-SCID mice that have a functional and well-organized humanized liver (17, 25). Importantly, these chimeric mice can be reproducibly infected with plasma-derived HCV strains representing all genotypes (20, 26) We have previously shown that polyclonal antibodies isolated from patient H in 2003 (H03) were able to prevent infection of these chimeric mice with the autologous virus that originally infected this patient in 1977 (H77) (16). During validation experiments to confirm the effectiveness of a new batch of purified antibodies isolated in 2006 (H06) it became clear that the amount of virus with which the animals are challenged has a major impact on the final outcome. The minimal dose of H77C virus that infects all inoculated animals (104 IU/mouse) could, as expected based on prior results (16), be neutralized by H06-antibodies. However, if the H06-treated chimeric mice were challenged with a 10-fold greater viral dose of H77C, two out of three animals became infected albeit with a considerable delay in the kinetics of the infection compared to non-treated control animals.

When we challenged H06-treated mice with the same dose (104 IU/mouse) of a genotype 4a HCV (strain ED43), only one of six challenged animals was completely protected from infection, again with a clear delay in the rise of viremia in the remaining animals compared to control animals. Heterologous in vivo neutralization of mHK6a virus of genotype 6a was more effective than mED43 neutralization. Although a ten-fold higher inoculum (105 IU/mouse) was injected, half of the H06-treated mice were completely protected. However, this higher dose was needed since a 5-fold lower dose (2×104 IU/mouse) of this isolate was not sufficient to establish a productive infection in all non-treated mice (data not shown).

Even though we showed here that polyclonal antibodies isolated from patient H can prevent or at least delay a heterologous infection in vivo, the efficacy of neutralization was less than what could be expected based on previous in vitro infections of cell cultures (14). In fact, those in vitro studies indicated that H06-cross-genotype neutralization would be 10- to 100-fold more effective than homologous neutralization. The reason for this discrepancy is still under investigation, however one could anticipate that the differences in structural characteristics between in vitro and in vivo produced virus could play a role.

To exclude the possibility that the lack of protection was caused by escape mutations we sequenced the complete envelope region of the seven H06-treated mice that became infected with mED43 or mHK6a viruses, and compared the amino acid sequence with those of viruses isolated from control animals and the original viral inocula. In four animals we did not observe any amino acid mutations in the envelope sequence using a direct sequencing method. The E1-sequence was completely conserved in all but one H06-treated animals. In this mED43-infected mouse we detected an L221M mutation. Since this mutation was also detected in one of the control animals it is unlikely to be the result of viral escape. In fact, this mutation corresponds to the wild type sequence retrieved from the patient virus from which this challenge virus originated (Y11604) (27). In one H06-treated animal a single mutation in the HVR1-region of the E2 protein was observed (S405P). It is doubtful that this mutation would provoke resistance to neutralization since antibodies that target HVR-1 usually are isolate specific. Likewise, another mutation (N573T) was observed in the variable intergenotypic region of E2, again arguing for spontaneous mutation. We also observed a mutation at position 448 in one HK6a-infected mouse (N448D), which is a known glycosylation site within E2. This is surprising since it has been shown by Helle and colleagues that a loss of glycosylation renders the virus more sensitive to neutralizing antibodies (28). In general, none of the mutations we have observed are located in previously reported conserved neutralizing epitopes. Using our direct sequencing approach it remains possible that we have missed certain mutations that are only present in a minor fraction of the virus pool. However, these would then not be the result of escape from neutralization since then they would have represented the major fraction of the circulating virus due to a competitive advantage over the wild type variants that are being neutralized by the H06-antibodies. Finally, the three animals with proven envelope mutations always experienced a delay in the appearance of viral RNA in the plasma; comparable to that of four H06-treated animals in which the viral amino acid sequence remained conserved. This again points towards a failure of neutralization rather than viral escape.

Despite this seemingly low cross-genotype neutralizing efficiency, our results are nevertheless encouraging for the quest for a potent cocktail of broad neutralizing monoclonal antibodies that could be used in a clinical setting for the prevention of graft re-infection after liver transplantation and holds promise for the development of a successful prophylactic HCV vaccine. First, only a minor fraction of the polyclonal H06-antibody pool is directed against HCV envelope proteins, and definitely not all of these antibodies will have neutralizing activity. Secondly, Zhang et al. recently showed that plasma from patient H contains antibodies against epitope II (residues 434–446 of E2) that interfere with the action of neutralizing antibodies (29). Depletion of these interfering antibodies from our H06-pool could possibly improve the protection rate. For this reason, the use of a pool consisting of well-defined monoclonal antibodies selected for their neutralizing ability would be more efficacious for prophylaxis than pooled non-fractionated polyclonal plasma (30–32).

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was supported by the Ghent University by a Concerted Action Grant (01G00507), by the European Union (6th framework – HEPACIVAC), by the Belgian State via the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Program (P6/36 – HEPRO), and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, NIH. JB is the recipient of a professorship at the University of Copenhagen with external funding from the Lundbeck Foundation. PM was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship and TV by a Ph.D. grant from The Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen).

List of abbreviations

- HCVpp

retroviral pseudoparticles containing HCV envelope proteins

- nAbs

neutralizing antibodies

- HCVcc

cell culture produced HCV

- H03

plasma isolated in 2003 from patient H

- H06

plasma isolated in 2006 from patient H

- uPA

urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- SCID

severe combined immune deficiency

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Contributor Information

Philip Meuleman, Email: Philip.Meuleman@ugent.be.

Jens Bukh, Email: JBUKH@niaid.nih.gov.

Lieven Verhoye, Email: Lieven.verhoye@ugent.be.

Ali Farhoudi, Email: Ali.Farhoudi@ugent.be.

Thomas Vanwolleghem, Email: Thomas.Vanwolleghem@ugent.be.

Richard Y. Wang, Email: RWang@cc.nih.gov.

Isabelle Desombere, Email: Isabelle.Desombere@ugent.be.

Harvey Alter, Email: HAlter@cc.nih.gov.

Robert H. Purcell, Email: RPURCELL@niaid.nih.gov.

Geert Leroux-Roels, Email: geert.lerouxroels@ugent.be.

References

- 1.Dustin LB, Rice CM. Flying under the radar: the immunobiology of hepatitis C. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:71–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:633–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M, Logvinoff C, Cheng-Mayer C, Rice CM, McKeating JA. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7271–7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832180100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartosch B, Bukh J, Meunier JC, Granier C, Engle RE, Blackwelder WC, Emerson SU, et al. In vitro assay for neutralizing antibody to hepatitis C virus: evidence for broadly conserved neutralization epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14199–14204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335981100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logvinoff C, Major ME, Oldach D, Heyward S, Talal A, Balfe P, Feinstone SM, et al. Neutralizing antibody response during acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10149–10154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403519101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meunier JC, Engle RE, Faulk K, Zhao M, Bartosch B, Alter H, Emerson SU, et al. Evidence for cross-genotype neutralization of hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles and enhancement of infectivity by apolipoprotein C1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501275102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapel HM, Christie JM, Peach V, Chapman RW. Five-year follow-up of patients with primary antibody deficiencies following an outbreak of acute hepatitis C. Clin Immunol. 2001;99:320–324. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu MY, Bartosch B, Zhang P, Guo ZP, Renzi PM, Shen LM, Granier C, et al. Neutralizing antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV) in immune globulins derived from anti-HCV-positive plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7705–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402458101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Blaser E, Schurmann P, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Patel AH, et al. Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6025–6030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607026104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fafi-Kremer S, Fofana I, Soulier E, Carolla P, Meuleman P, Leroux-Roels G, Patel AH, et al. Viral Entry and Escape from Antibody-Mediated Neutralization Influence Hepatitis C Virus Re-infection in Liver Transplantation. J Exp Med. 2010 doi: 10.1084/jem.20090766. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med. 2005;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, et al. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheel TK, Gottwein JM, Jensen TB, Prentoe JC, Hoegh AM, Alter HJ, Eugen-Olsen J, et al. Development of JFH1-based cell culture systems for hepatitis C virus genotype 4a and evidence for cross-genotype neutralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:997–1002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711044105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottwein JM, Scheel TK, Jensen TB, Lademann JB, Prentoe JC, Knudsen ML, Hoegh AM, et al. Development and characterization of hepatitis C virus genotype 1-7 cell culture systems: role of CD81 and scavenger receptor class B type I and effect of antiviral drugs. Hepatology. 2009;49:364–377. doi: 10.1002/hep.22673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanwolleghem T, Bukh J, Meuleman P, Desombere I, Meunier JC, Alter H, Purcell RH, et al. Polyclonal immunoglobulins from a chronic hepatitis C virus patient protect human liver-chimeric mice from infection with a homologous hepatitis C virus strain. Hepatology. 2008;47:1846–1855. doi: 10.1002/hep.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, De Vos R, de Hemptinne B, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Roskams T, et al. Morphological and biochemical characterization of a human liver in a uPA-SCID mouse chimera. Hepatology. 2005;41:847–856. doi: 10.1002/hep.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meuleman P, Vanlandschoot P, Leroux-Roels G. A simple and rapid method to determine the zygosity of uPA-transgenic SCID mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:375–378. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piet MP, Chin S, Prince AM, Brotman B, Cundell AM, Horowitz B. The use of tri(n-butyl)phosphate detergent mixtures to inactivate hepatitis viruses and human immunodeficiency virus in plasma and plasma’s subsequent fractionation. Transfusion. 1990;30:591–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30790385516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bukh J, Meuleman P, Tellier R, Engle RE, Feinstone SM, Eder G, Satterfield WC, et al. Challenge pools of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1-6 prototype strains: replication fitness and pathogenicity in chimpanzees and human liver-chimeric mouse models. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1381–1389. doi: 10.1086/651579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottwein JM, Scheel TK, Callendret B, Li YP, Eccleston HB, Engle RE, Govindarajan S, et al. Novel infectious cDNA clones of hepatitis C virus genotype 3a (strain S52) and 4a (strain ED43): genetic analyses and in vivo pathogenesis studies. J Virol. 2010;84:5277–5293. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02667-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meuleman P, Hesselgesser J, Paulson M, Vanwolleghem T, Desombere I, Reiser H, Leroux-Roels G. Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology. 2008;48:1761–1768. doi: 10.1002/hep.22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoll-Keller F, Barth H, Fafi-Kremer S, Zeisel MB, Baumert TF. Development of hepatitis C virus vaccines: challenges and progress. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:333–345. doi: 10.1586/14760584.8.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindenbach BD, Meuleman P, Ploss A, Vanwolleghem T, Syder AJ, McKeating JA, Lanford RE, et al. Cell culture-grown hepatitis C virus is infectious in vivo and can be recultured in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3805–3809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lootens L, Meuleman P, Pozo OJ, Van Eenoo P, Leroux-Roels G, Delbeke FT. uPA+/+-SCID mouse with humanized liver as a model for in vivo metabolism of exogenous steroids: methandienone as a case study. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1783–1793. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.119396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercer DF, Schiller DE, Elliott JF, Douglas DN, Hao C, Rinfret A, Addison WR, et al. Hepatitis C virus replication in mice with chimeric human livers. Nat Med. 2001;7:927–933. doi: 10.1038/90968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamberlain RW, Adams N, Saeed AA, Simmonds P, Elliott RM. Complete nucleotide sequence of a type 4 hepatitis C virus variant, the predominant genotype in the Middle East. J Gen Virol. 1997;78 (Pt 6):1341–1347. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helle F, Goffard A, Morel V, Duverlie G, McKeating J, Keck ZY, Foung S, et al. The neutralizing activity of anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies is modulated by specific glycans on the E2 envelope protein. J Virol. 2007;81:8101–8111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang P, Zhong L, Struble EB, Watanabe H, Kachko A, Mihalik K, Virata-Theimer ML, et al. Depletion of interfering antibodies in chronic hepatitis C patients and vaccinated chimpanzees reveals broad cross-genotype neutralizing activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7537–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson DX, Voisset C, Tarr AW, Aung M, Ball JK, Dubuisson J, Persson MA. Human combinatorial libraries yield rare antibodies that broadly neutralize hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16269–16274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705522104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law M, Maruyama T, Lewis J, Giang E, Tarr AW, Stamataki Z, Gastaminza P, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat Med. 2008;14:25–27. doi: 10.1038/nm1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broering TJ, Garrity KA, Boatright NK, Sloan SE, Sandor F, Thomas WD, Jr, Szabo G, et al. Identification and characterization of broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies directed against the E2 envelope glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2009;83:12473–12482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]