Abstract

Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells (Treg) is required for development and suppressive function. How different inflammatory signals affect Foxp3 chromatin structure, expression, and Tregs plasticity are not completely known. In the present study, the Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) ligand peptidoglycan inhibited Foxp3 expression in both natural Treg (nTreg) and TGFβ-driven adaptive Treg (aTreg). Inhibition was independent of paracrine Th1, Th2 and Th17 cytokines. PGN-induced T cell intrinsic TLR2-Myd88 dependent IFR1 expression, and induced IRF1 bound to IRF1 response elements (IRF-E) in the Foxp3 promoter and intronic enhancers, and negatively regulated Foxp3 expression. Inflammatory IL-6 and TLR2 signals induced divergent chromatin changes at the Foxp3 locus and regulated Treg suppressor function, and in an islet transplant model resulted in differences in their ability to prolong graft survival. These findings are important for understanding how different inflammatory signals can affect the transplantation tolerance and immunity.

Keywords: Foxp3, Toll-like receptor, Interferon regulatory Factor 1, Inflammation, Tolerance, Epigenetics

Introduction

Regulatory suppressive T cells play important roles in the homeostasis of the immune response. Foxp3 is a forkhead family transcription factor required for the development and function of Treg. Foxp3 defines the Treg phenotype, and recent reports demonstrate that, contrary to previous notions, its expression is not necessarily stable (1–3). Treg have decreased Foxp3 expression and suppressive function at sites of inflammation (4, 5), and adoptive transfer of Treg to lymphopenic hosts or using genetically marked Treg, has shown that 10–15% of nTreg loose Foxp3 expression. These “exTreg” acquire an activated or memory phenotype and cause autoimmunity (3). Several factors might be responsible for the development of “exTreg”. Deficiency of IL-2 or presence of IL-1, IL-4, IL-6, IL-23 and IFNγ may down regulate Treg suppressive function (2, 4, 6–10). We previously demonstrated that IL-6 inhibits Foxp3 transcription by inducing methylation of an upstream Foxp3 CpG island enhancer (2), while others have shown that IL-6 regulates the transcriptional activity of the Foxp3 protein through acetylation (8). The significance of multiple mechanisms to down regulate Foxp3 expression and its consequences for immune regulation is not known.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are members of a family of innate immune signaling receptors that recognize conserved pathogen associated microbial patterns, and play important functions in host defense as well as adaptive immunity. There are several known endogenous TLR ligands such as HMGB1, Hsp60, hyaluronan, extradomain A of fibronectin, heparan sulphate, and exogenous products such as bacterial lipoprotein, peptidoglycan, flagellin, lipopolysaccharide, CpG DNA and double stranded viral RNA (11). These ligands are present at the site of injury or during infection, and stimulate specific TLRs on T cells and antigen presenting cells (APCs) to induce pro-inflammatory cytokines (12). TLR2 agonists induce secretion of large amounts of IL-6 from APC, that can reverse the suppressive function of Treg (7). APC derived IL-6 in combination with TGFβ also induces Th17, leading to enhanced inflammation in infectious colitis (13) and prevention of transplantation tolerance (14). TLR2 is expressed on both CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ T cells (15, 16). Some investigators reported that stimulation with TLR2 ligands suppress Treg function (7, 15, 17–20), whereas others found enhancement (16, 21, 22). It has been reported that TLR2 induced loss of Treg function is not due to modulation of CTLA-4 or glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor expression, but due to down regulation of Foxp3 expression (15). Thus, if and how TLR2 signaling perturb Foxp3 expression and Treg function are not clearly understood.

In the present study, we show that the TLR2 ligand peptidoglycan (PGN), derived from Staphylococcus aureus, directly inhibits TGFβ induced Foxp3 expression in naïve CD4+CD25− T cells, as well as constitutive expression of Foxp3 in CD4+CD25+ nTreg. TLR2 stimulation induces large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-6 and IFNγ in naïve CD4+CD25− T cells. However, TLR2 induced inhibition of Foxp3 is independent of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4 and STAT6, but dependent on Myd88 and IRF1. IRF1 binds to the IRF-E present in the proximal promoter and intronic enhancer region at the Foxp3 locus, and negatively regulates the transcription of Foxp3 to suppress Treg function. Importantly, by comparing the structure of Foxp3 in nTreg exposed to IL-6 or to PGN, we demonstrated mechanisms that differentially modulate Foxp3 chromatin structure and its expression. This has major consequences for subsequent T cell differentiation, fate, and suppressive function. These findings provide a basis for rational design of protocols to modulate immunization or tolerance during inflammation or infection.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Purified peptidoglycan (PGN) from Staphylococcus aureus was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Fluka), Buchs, Switzerland. Recombinant purified mouse IL-2, recombinant mouse IL-6, recombinant human TGFβ1, functional grade purified anti-mouse CD3ε (145-2C11), functional grade purified anti-mouse IL-6 (MP5-20F3), PE anti-mouse CD8 (53–6.7), APC anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5), FITC anti-mouse CD25 (PC61.5), FITC anti-mouse IFNγ (XMG1.2), PE anti-mouse IL-17 (eBio17B7), PE anti-mouse/rat Foxp3 (FKJ-16s) antibody, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), ionomycin, monensin and isotype control antibodies were purchased from e-Bioscience (San Diego, CA). Purified Rat anti-mouse IL-6R (D7715A7) was purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Rabbit anti-mouse acetylated histone H3 (Lys 9/14), rabbit polyclonal IRF-1 antibody (M-20), rabbit polyclonal Runx1 antibody and control antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-mouse Foxp3 polyclonal antibody was from Abcam (San Francisco, CA).

Mice

BALB/c, C57BL/6, TLR2−/−, STAT1−/−, IL-6−/−, STAT4−/−, STAT6−/− and IRF1−/− mice 8–10 weeks old were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. STAT3fl/fl:CD4-cre mice were maintained by Dr. David Levy, New York University. Myd88−/− mice were provided by Dr. Maria Abreu, University of Miami. Foxp3gfp reporter mice were from Dr. Alexander Rudensky, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. All mutant mice were on the C57BL/6 background except for the STAT6−/− on the BALB/c background. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility in microisolator cages. All experiments used age- and sex-matched mice in accordance with protocols approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee.

Purification and culture of mouse T cells

Cells were purified and cultured as described earlier(2). Briefly, flow cytometric sorted splenic CD4+CD25− T cells (50000 cells/well) were cultured with T cell depleted irradiated (800 rad) syngenic splenocytes (50000 cells/well) in the presence of soluble anti-CD3ε antibody (1μg/ml), IL-2 (10 ng/ml), TGFβ (5 ng/ml) with or without PGN (10μg/ml) in a final volume of 200μl complete RPMI medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1× non-essential amino acids, and 2 × 10−5M 2-mercaptoethanol) in U-bottomed 96 well plates (Corning Inc, Lowell, MA). Cells were cultured for 4 days, unless otherwise stated, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell staining and flow cytometric analysis

Staining was performed with the specific indicated antibodies (1μg/106 cells) at 4°C for 30 minutes. Cells were analyzed using the FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). Intracellular Foxp3 staining was performed using Foxp3 staining kit (e-Bioscience).

Quantitative real-time RT PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was purified and cDNA was made using oligo d(T)12–14 primer and Superscript RT kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described earlier(2). mRNA expression levels were quantified by real-time PCR using SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with the LightCycler 2.0 (Roche Diagnostic Corp, Indianapolis, IN). Primers sequences are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Luminex ELISA

Culture supernatants were collected at the end of T cell culture and cytokines were quantitated using Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine TH1/TH2 assay kit. Assays were conducted according to manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed on a Bio-Plex 200 System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Microscopic analysis

Purified CD4+ T cells were stained with APC conjugated anti-CD4 mAb, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, washed, permeabilized using 0.25% Triron-X-100 in PBS, and incubated with purified rabbit anti-IRF1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and biotin conjugated Foxp3 mAb (FKJ-16s; eBioscience). Cells were stained with Cy3 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG F(ab)2 and FITC conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoReserach, West Grove, PA). Cells were placed on a glass slide by cytospin, mounted with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) containing mounting medium (Vector Laboratories), and imaged under a fluorescent microscope (Leica DM-RA2, Germany) using openLab 5.5 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed using the ChIP kit (Upstate USA, Charlottesville, VA) as described earlier (2). Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Construction of luciferase vector and luciferase reporter assay

Genomic DNA was purified from naïve CD4+CD25− T cells. The Foxp3 intronic enhancer containing IRF-1, NFAT, SMAD3 or all the three binding elements was amplified using specific primers given in Supplementary Table 1.

Amplified PCR products were cloned into the Kpn1 and BglII sites of the pGL3 promoter vector (Promega, Madison, WI) proximal to the minimal SV40 promoter. The BW5147.3 cell line, a mouse T cell lymphoma, was purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). BW5147.3 (1 × 106 cells) were transfected with the pGL3 promoter vector or recombinant pGL3 construct (3.0 μg) using TransFast Transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). Synthetic Renilla luciferase reporter vector (pRL-TK, 0.3μg, Promega) was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested and luciferase activity was measured using the dual luciferase assay system (Promega). Data were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. IRF-1 and IRF-2 plasmid constructs were generously provided by Dr. Tadatsugu Taniguchi, University of Tokyo, Japan (23).

Islet transplantation

Islets were purified and transplanted under kidney capsule as previously described (1). C57BL/6 male recipient mice were rendered diabetic by a single intraperitoneal injection of 180 mg/kg of streptozotocin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at least 1 week previously. Diabetes was confirmed by hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dl blood glucose) for two consecutive days. Five hundred fifty freshly isolated BALB/c islets were transplanted to the subcapsular space of the right kidney. Blood glucose was monitored daily to assess islet graft function. Reversal of diabetes was defined as blood glucose <200 mg/dl on two consecutive daily measurements. Grafts were considered to be rejected if blood glucose was >250 mg/dl on two consecutive daily measurements.

Statistical analysis

Values are given as mean of the individual samples ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. Differences in graft survival times were assessed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with Logrank Test using GraphPad Prism 4.0c software. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

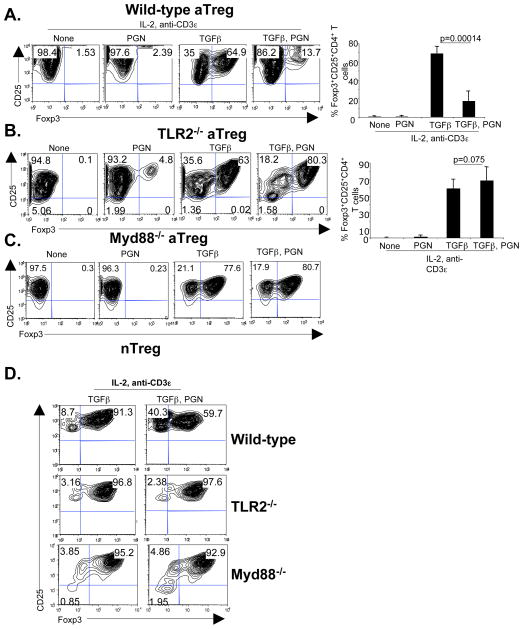

TLR2 stimulation inhibits constitutive and TGFβ induced Foxp3 expression

There are conflicting reports about the role of TLR2 ligands in Foxp3 expression and Treg function (7, 15–18, 21, 22). To investigate the effect of TLR2 stimulation on Foxp3 expression, naïve CD4+CD25− T cells or CD4+CD25+ nTreg were cultured with IL-2, anti-CD3ε mAb, TGFβ and the TLR2 ligand PGN for 4 days. The results showed that TLR2 stimulation inhibited TGFβ induced Foxp3 protein (Figure 1A) and mRNA expression in naïve CD4+CD25− T cells (Figure S1A) in dose dependent manner (Figure S1B). PGN induced inhibition was dependent on TLR2 (Figure 1B) and the downstream adaptor protein Myd88 (Figure 1C). TLR2 expression on CD4+ T cells was specifically required for inhibitory function (Figure S1C). PGN also inhibited Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+ nTreg and was TLR2 and Myd88 dependent (Figure 1D). Together, these results demonstrated that TLR2 agonists inhibited Foxp3 expression in both nTreg and aTreg via TLR2 and Myd88.

Figure 1. TLR2 ligand inhibits Foxp3 expression.

(A) Purified CD4+CD25− T cells (50000 cells/well) from C57BL/6 mice were cultured with irradiated syngeneic T cell depleted splenocytes (5 × 104 cells/well) in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng/ml), anti-CD3ε mAb (1 μg/ml), TGFβ (5 ng/ml) or PGN (10 μg) for 4 days. Intracellular Foxp3 was analyzed by gating on CD4+ cells. Values in the quadrants are the percentage of cells (left). Pooled data from 7 independent experiments showing mean and standard deviation of percent CD4+Foxp3+ cells (right). (B) CD4+CD25− naive T cells from TLR2−/− mice were cultured as in (a). Intracellular Foxp3 was analyzed by gating on CD4+ cells. Representative data from one experiment (left). Pooled data from 6 independent experiments (right). (C) CD4+CD25− T cells from Myd88−/− mice were cultured as in (A). Data shown is representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) CD4+CD25+ nTreg from wild-type, TLR2−/− or Myd88−/− mice were cultured as in (A). Intracellular Foxp3 was analyzed by gating on CD4+ cells. Representative data from 3 independent experiments. p=0.003 for WT (TGFβ) nTreg vs. WT (TGFβ γPGN) nTreg.

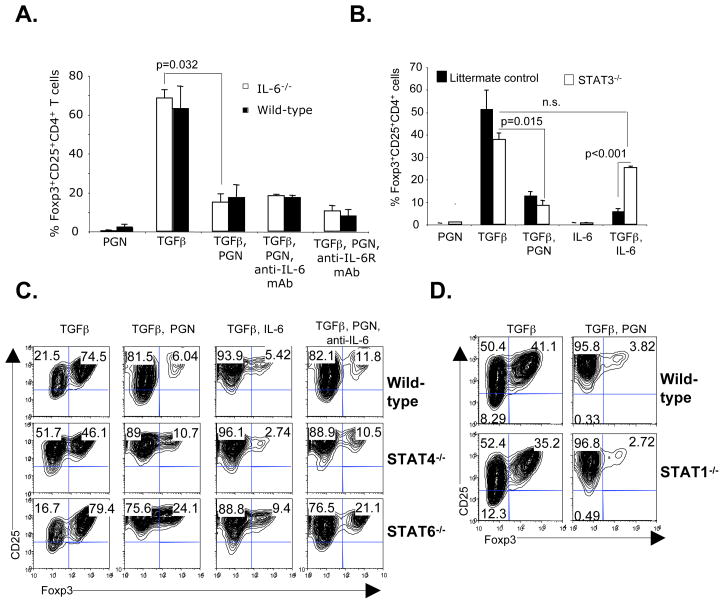

TLR2 stimulated inhibition of Foxp3 is independent of cytokines

Bacterial derived TLR2 ligands induce pro-inflammatory cytokines in CD4+CD25− T cells (Figure S2A and Figure S2B). Proinflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-4 or IL-6 inhibit Foxp3 expression (2, 9, 24, 25). In particular, IL-6 plus TGFβ is known to inhibit Foxp3 expression and Treg function (2, 8, 15). To investigate the role of PGN-induced IL-6 in inhibition of Foxp3 expression, CD4+CD25− T cells were purified from IL-6−/− mice and stimulated in the presence of PGN. The results showed that TLR2 stimulation still inhibited Foxp3 expression in IL-6−/− T cells (Figure 2A). Similarly, adding blocking mAb against IL-6 or IL-6R to wild-type CD4+CD25− T cells did not prevent TLR2 stimulated inhibition of Foxp3 (Figure 2A). Since IL-6 signals through STAT3, STAT3 deficient CD4+CD25− T cells from STAT3fl/fl:CD4-cre mice were used. The results showed that while IL-6 inhibited Foxp3 expression in wild-type but not in STAT3 deficient cells, TLR2-induced inhibition of Foxp3 expression was independent of STAT3 (Figure 2B). Together, these results demonstrated that IL-6 independent and a T cell intrinsic signaling pathway, was responsible for TLR2 inhibition of Foxp3 expression.

Figure 2. PGN induced inhibition of Foxp3 expression is independent of IL-6, IL-6R, STAT1, STAT3, STAT4 and STAT6.

(A) Purified CD4+CD25− T cells from wild-type or IL-6−/− mice were cultured as in Figure 1A in the presence of the indicated reagents (anti-IL-6, 10 μg/ml; anti-IL-6R, 10 μg/ml). Intracellular Foxp3 was analyzed by gating on CD4+ cells. Pooled data showing the mean percentages of Foxp3+ cells from 3 independent experiments. (B) STAT3−/− (CD4 Cre:STAT3 f/f) or littermate control CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated reagents. Pooled data showing the mean percentages from 3 independent experiments. (C) STAT4−/− and STAT6−/− CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured and Foxp3 expression determined. Representative data of 2 independent experiments. (D) STAT1−/− CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated reagents. Representative data of 2 independent experiments.

Since activation of naïve CD4+CD25− T cells in the presence of PGN-induced multiple Th1 and Th2 lineage specific cytokines (Figure S2A and S2B), we further investigated their role. IL-4 signals through STAT6 and inhibits Foxp3 expression, and in combination with TGFβ induces IL-9 producing cells (9). IL-12 signals through STAT4 and induces differentiation of Th1 cells. STAT1 is involved in the IFNγ signaling, and along with TGFβ inhibits development of aTreg (26). STAT1−/−, STAT4−/− and STAT6−/− CD4+CD25− T cells were each stimulated in the presence of PGN. The results showed TLR2 stimulation inhibited Foxp3 expression in these gene deficient T cells (Figure 2C and 2D), demonstrating that these transcription factors and their associated cytokine signaling pathways did not play an important role in TLR2 inhibition of Foxp3 expression. Additionally, combinations of anti-IL-6 with STAT4 or STAT6 deficiency did not restore Foxp3 expression (Figure 2C), while STAT4 or STAT6 deficiency did not alter the response to IL-6 (Figure 2C). Together, the results showed that the paracrine actions of multiple cytokines were not responsible for TLR2 stimulation inhibited Foxp3, and that there was a T cell intrinsic mechanism of suppression.

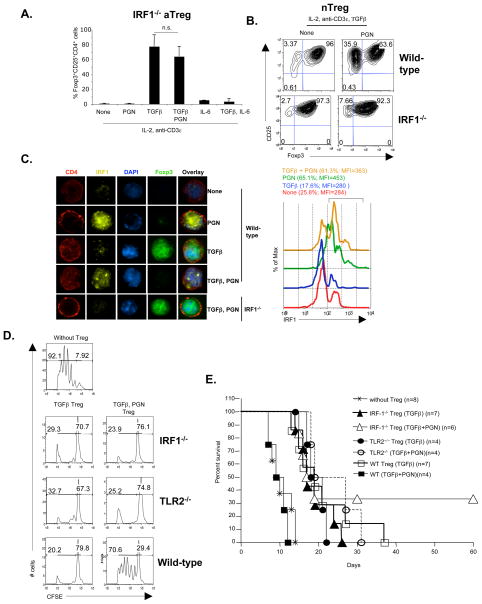

TLR2 stimulated inhibition of Foxp3 expression is dependent on IRF1

Since TLR2 inhibition of Foxp3 expression was not mediated by many different secreted cytokines, we hypothesized that signals downstream of TLR2-Myd88 might act as negative regulators for Foxp3 transcription. It was shown that IRF1 directly interacts with Myd88, and activation through TLR leads to IRF1 mobilization into the nucleus (27, 28). To investigate the role of IRF1 in TLR2 stimulated inhibition of Foxp3, IRF1−/− CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured with PGN for 4 days. The results showed that IRF1−/− T cells were not susceptible to TLR2 stimulated inhibition of Foxp3 expression (Figure 3A), and T cell intrinsic IRF1 expression was required for complete inhibition of Foxp3 expression (Figure S3A). IRF1−/− CD4+CD25+ nTreg also were not susceptible to TLR2 stimulated inhibition (Figure 3B); and naïve IRF1−/− mice had increased numbers of Foxp3+CD4+ nTreg in vivo (Figure S3B). Quantitative RT-PCR and immunofluorescence microscopy showed increased IRF1 expression and nuclear localization after TLR2 stimulation (Figure 3C and S3C). These results demonstrated that IRF1 was downstream of the TLR2/Myd88 pathway, and was responsible for TLR2 stimulated inhibition of Foxp3 expression.

Figure 3. PGN induced inhibition of Foxp3 expression and Treg mediated suppression is dependent on IRF-1.

(A) CD4+CD25− T cells from IRF1−/− mice were cultured as in Figure 1A. Intracellular Foxp3 expression was analyzed gating on CD4+ cells. Pooled data showing the mean percentages of cells from 7 independent experiments. (B) CD4+CD25+ nTreg from wild-type or IRF1−/− male mice were cultured as indicated. Intracellular Foxp3 expression analyzed by gating on CD4+ cells. (C) After 4 days of culture, the cells from (A) were surface stained for CD4 and intracellularly for Foxp3, IRF-1 and DNA (DAPI), and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (left, magnification ×1000) and flow cytometry (right). Representative data of 2 independent experiments. (D) Freshly isolated CD4+CD25− T cells from C57BL/6 male were purified, labeled with CFSE, and cultured (5 × 104 cells/well) with the indicated Treg subsets (5 × 104 cells/well) in the presence of irradiated T cell depleted syngenic splenocytes (5 × 104 cells/well) and anti-CD3ε mAb (1 μg/ml) for 72 hours. Proliferation of responder T cells was measure by CFSE dilution. Percentage cells divided (left bracket) and undivided (right bracket) are shown. Representative data of 3 independent experiments. p<0.05 for undivided cells of WT (TGFβ + PGN) Treg vs. WT (TGFβ), TLR2−/− (TGFβ + PGN) and IRF1−/− (TGFβ + PGN) Treg. (E) Strepozotocin induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice received BALB/c islets (550 islets/mouse) underneath the right kidney capsule, along with the indicated aTreg (1 × 106 cells/mouse) injected intravenously. p<0.05 for WT (TGFβ + PGN) Treg vs. WT (TGFβ), TLR2−/− (TGFβ + PGN) and IRF1−/− (TGFβ + PGN) Treg.

Endogenous IL-6 in culture did not strongly inhibit Foxp3 (Figure 2A), while addition of exogenous IL-6 prevented Foxp3 expression in IRF1−/− T cells (Figure 2A), demonstrating that the IL-6-IL-6R-STAT3 pathway of Foxp3 and Treg inhibition was separable from the TLR2-Myd88-IRF1 pathway. Since TLR2−/− and IRF1−/− naïve CD4+CD25− T cells stimulated with TGFβ plus PGN still expressed Foxp3 (Figure 1B and 3A), they were assessed for suppressor activity on CD4+CD25− responder T cells in vitro. The results showed that IRF1−/− and TLR2−/− Treg cultured with or without PGN had identical suppressor activity, whereas wild-type T cells cultured with TGFβ plus PGN had almost no suppressor function (Figure 3D). In vivo transfer of IRF1−/− aTreg cultured with or without PGN prolonged islet allograft survival as well as wild-type Treg, showing that these Treg maintained their suppressor function in vivo (Figure 3E). In contrast, wild-type aTreg cultured with PGN had no suppressor activity in vivo. These results demonstrated that TLR2−/− and IRF1−/− induced Treg were not sensitive to TLR2 stimulation, and maintained suppressor function both in vitro and in vivo.

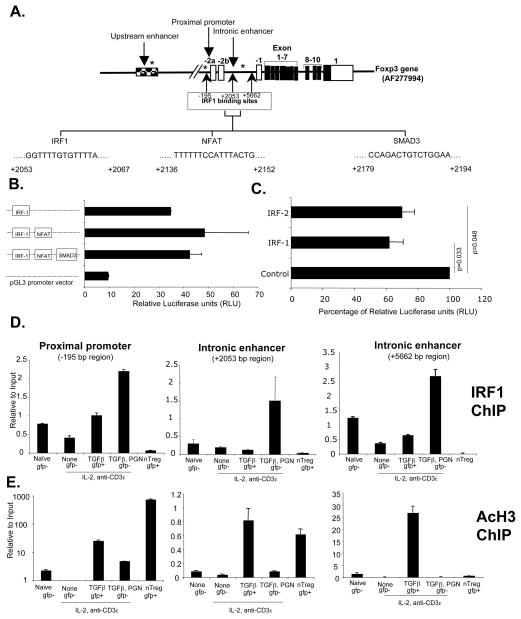

IRF1 is a negative regulator of Foxp3 transcription, and IRF1−/− aTregs are suppressive

The Foxp3 locus possesses 3 IRF-E (Figure 4A). One of the IRF-E is present at the proximal promoter (−195bp), a region involved in Foxp3 expression, although the signals that regulate this element in CD4 T cells are not defined (29). There are two other IRF-E sites between non-coding exons -2b and -1 (+2052bp and +5662bp, respectively) (Figure 4A). One of the IRF-E sites (+2052bp) is very close to the known NFAT and SMAD3 binding intronic enhancer region, which possesses TGFβ sensitive enhancer activity and is involved in regulation of Treg (30). We hypothesized that this IRF1 binding site might function in the negative regulation of Foxp3 transcription. To test this, these IRF1, NFAT and SMAD3 binding elements were cloned into a luciferase reporter vector, and enhancer activity was monitored using the BW5147 T cell lymphoma cell line. The results showed that the +2052bp IRF1 binding region had enhancer activity (Figure 4B) and this activity was not augmented by the NFAT or SMAD3 elements. Over-expression of IRF1 partially inhibited enhancer activity (Figure 4C). ChIP analysis of T cells showed that TLR2 stimulation enhanced the binding of IRF1 to all three regions (Figure 4D) and also decreased their acetylated histone 3 (AcH3) at these sites (Figure 4E). It should be noted that IRF1 binds to the intronic enhancer (+5662 bp region) (Figure 4D), but this region showed AcH3 only in aTreg but not in nTreg (Figure 4E), suggesting that this region is functional predominantly in aTreg. These results are consistent with TLR2-stimulated expression of IRF1, which subsequently bound all three IRF-E regions, changed Foxp3 gene structure, and negatively regulated Foxp3 transcription.

Figure 4. IRF1 binds to the Foxp3 locus and negatively regulates Foxp3 expression.

(A) Schematic representation of Foxp3 gene. Sites marked with asterisk (*) represents CpG DNA methylation site (B) BW5147.3 lymphoma T cells were transfected with control vector (pGL3) or Foxp3 intronic enhancer region (near +2053 bp) containing plasmids (3 μg). Luciferase activity was monitored 48 hours after transfection. For transfection efficiency control, Renilla luciferase vector (pRL-TK, 0.3 μg) was co-transfected, and the data were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. (C) pGL3-promoter vector containing only IRF1 binding region (3 μg) was co-transfected along with control plasmid pCAG, or IRF-1 or IRF-2 expressing pCAG plasmids (9 μg). Luciferase activity was monitored 48 hours after transfection as in 4C. (D) Purified CD4+CD25−Foxp3gfp− T cells from Foxp3gfp reporter male mice were cultured as indicated. CD4+CD25+Foxp3gfp− or CD4+CD25+Foxp3gfp+ cells were then purified using flow cytometry, and IRF1 binding at Foxp3 proximal promoter and intronic enhancers was analyzed by ChIP assay. (E) Histone 3 acetylation at the Foxp3 promoter, intronic regions was analyzed by ChIP assay. Representative data of two independent experiments. Error bars are standard deviation.

Plasticity of Treg Foxp3 expression

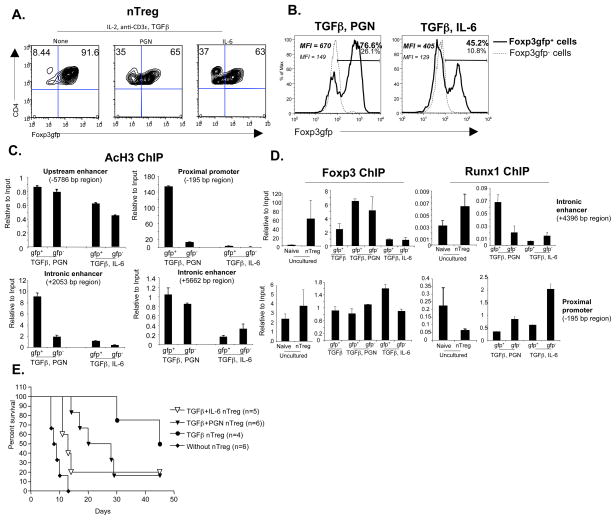

The current data, our previous reports (2), and others (3, 8, 31) have shown multiple molecular pathways for either inhibition or ablation of Foxp3 expression and Treg function. The important question is whether these diverse pathways have alternate physiological consequences for T cell differentiation, fate, or function. We first investigated the stability of Foxp3 expression by culturing CD4+CD25+Foxp3gfp+ nTreg in the presence of PGN or IL-6, and monitoring Foxp3. The results showed that IL-6 as well as PGN inhibited Foxp3 expression after 5 days of culture (Figure 5A). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Foxp3gfp+ and Foxp3gfp− cells from these cultures revealed that TLR2 stimulation induced both IFNγ and IL-17 expression, while IL-6 induced IL-17 but inhibited IFNγ (Figure S4), suggesting different T cell fates. To further evaluate Foxp3 expression and the fate of Foxp3gfp− “exTreg” and Foxp3gfp+ Treg, the gfp− and gfp+ populations from these primary cultures were separately harvested, washed, rested for 1 day, and placed back into culture. The results showed that Foxp3gfp− “exTreg” from both the PGN and IL-6 groups did not regain Foxp3 expression. This was true even if TGFβ was added to the culture (not shown). The Foxp3gfp+ Treg previously exposed to IL-6 continued to lose Foxp3gfp expression so that 55 % of these cells become Foxp3gfp− by the end of secondary culture (Figure 5B). In contrast, the Foxp3gfp+ Treg previously treated with PGN continued to express Foxp3gfp and only a small percent became Foxp3gfp− (Figure 5B). This suggests that IL-6 and TLR2 differentially affected Foxp3 gene structure and T cell fate.

Figure 5. IL-6 induces persistently decreased Foxp3 expression compared to TLR2.

(A) Purified CD4+CD25+Foxp3gfp+ T cells were cultured as in Figure 1a for 5 days. Foxp3gfp expression was analyzed by gating on CD4+ T cells. Representative data of 3 independent experiments. (B) CD4+Foxp3gfp+ and CD4+Foxp3gfp− T cells purified from the cultures in (A) were rested for 24 hours in the presence of IL-2 (20 ng/ml) and irradiated T cell depleted splenocytes. Cells were then re-stimulated with anti-CD3ε, and IL-2 for another 5 days. Foxp3 expression was analyzed by gating on CD4+ cells. Representative data of 3 independent experiments. (C) Cells from (B) were isolated, and acetylation of histone 3 at the indicated Foxp3 regulatory regions was analyzed by ChIP assay. Error bars represent standard deviations; data are representative of two independent experiments. (D) Foxp3 and Runx1 protein binding to Foxp3 locus in freshly isolated CD4+Foxp3gfp− naïve T cells or CD4+Foxp3gfp+ nTreg (left) or 4-day cultured nTreg as in (C). Error bars represent standard deviations; data are representative of two independent experiments. (E) STZ induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice received BALB/c islets under the kidney capsule along with the indicated purified cultured Foxp3gfp+ nTreg (1 × 106 cells/mouse) intravenously. p value for without Treg vs. TGFβ nTreg (<0.01) and vs. TGFβ +PGN nTreg (<0.001).

We previously showed that IL-6 induced re-methylation of CpG residues and decreased AcH3 in the upstream enhancer of the Foxp3 gene, thereby inhibiting Foxp3 expression (2). To investigate the chromatin structure of Foxp3 gene regulatory elements in Foxp3gfp+ and Foxp3gfp− Treg from PGN- and IL-6-stimulated cultures, ChIP assays for AcH3 were performed at four different regions of the Foxp3 locus. The results showed that PGN decreased AcH3 at the proximal promoter (−195 bp region) and the intronic enhancer (+2053 bp region), whereas IL-6 AcH3 at all four regions (Figure 5C), suggesting that IL-6 induced stronger repression compared to PGN. The Foxp3 protein together with Runx1 (Runt-related transcription factor 1) and Cbf-β (core-binding factor β, a common cofactor for all Runx protein) interact at the Foxp3 locus to provide help for stable gene expression (32, 33). IL-6 strongly inhibited the binding of Foxp3 protein to the Foxp3 intronic enhancer (+4396), whereas PGN did not result in this change (Figure 5D). IL-6 also inhibited Runx1 binding at the intronic enhancer while PGN had less inhibitory effect (Figure 5D). Other regulatory regions, such as the proximal promoter, did not have differential binding inhibition of Foxp3 or Runx1 protein in IL-6 or PGN-stimulated nTreg (Figure 5D). Lastly, Foxp3gfp+ nTreg exposed to IL-6 possessed markedly reduced suppressive activity in vivo for prolonging survival of allogeneic islets compared to PGN treated Treg (Figure 5E). Together, these data suggest that IL-6 induced strong chromatin remodeling at the Foxp3 locus compared to PGN, and reprogrammed the nTreg in such a way that re-expression or maintenance of Foxp3 were not allowed, even after removal or inhibitory signals, with the consequent loss of suppressor function.

Discussion

TLR2 is stimulated by many ligands including lipoteichoic acids, peptidoglycans, lipomannans, zymosans, phenol-soluble modulins, hsp70, hsp72 and lipopeptides. There are reports that TLR2 ligands enhance aTreg function (21, 22) as well as enhance the suppressive function of nTreg (16). The differences from the present report might be due to the sources of TLR2 ligands and specificity of those ligands for TLR2. For example, viral derived TLR2 ligands induce type I interferons, whereas bacterial origin ligands do not (34). TLR2 can interact with TLR1 or TLR6, and the heterodimer of TLR1/2 recognizes bacterial triacyl lipopeptides (Gram negative bacterium and mycobacteria), whereas TLR2/6 recognizes bacterial diacyl lipopeptides (Gram positive bacteria and mycoplasma) (11, 35, 36). Acylation status of TLR2 ligands determines the interaction and induction of TLR2-TLR1/TLR6 heterodimerization, and subsequent immunological function (36). TLR2 ligands, such as peptidoglycan among others, have no hydrophobic acylated moieties that can be inserted into the TLR2 pocket for binding, and must interact either with different regions of the TLR2 heterodimer or require other co-receptors for its downstream signaling. However, it is not known which other co-receptors if any may be required to recognize S. aureus PGN. Therefore, it is possible that TLR2 ligands with different structures may have different recognition pathways and immunological functions. Bacterial pathogens express a variety of ligands that can be sensed not only through extracellular receptors such as TLRs, but also intracellular Nod-like receptors (NLRs). TLR2 and NLR recognize structurally similar ligands (37). Similar to TLRs, Nod1 and Nod2 activate gene transcription through NF-kB and MAP kinase signaling pathways via adaptor molecules RICK (RIP2) and CARD9 (37). MAP kinase signaling is required for the differentiation of Treg (38). These observations suggest that stimulation of Nod1/Nod2 alone or together with TLR may differentially regulate Foxp3 expression compared to TLR or NLR ligands alone.

IRF1 plays an important role in immune regulation, and cytokines such as IFNγ induce IRF1 and IRF-2 expression (39). IRF1 was originally identified as a transcriptional activator, but it was later shown that the N-terminal 60 amino acids of IRF1 possess an inhibitory domain involved in transcriptional repression (40). Elser et al. showed that the IL-4 promoter possesses 3 different IRF-E, and IFNγ induces binding of IRF1 and IRF2 to these sites and negatively regulates IL-4 expression (41). In IRF1 deficient mice, CD4+ T cells are more Th2 polarized and produce more IL-3, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-6 compared to wild-type mice (41). Commensurate with this, our data showed that intrinsic signaling induced by PGN stimulated IRF1 expression and inhibited Th2 cytokines secretion or Treg differentiation in wild-type T cells. Together, these studies showed that IRF1 signaling favors Th1 over Th2 or Treg.

Different regulatory elements of the Foxp3 locus respond to various signals (42). Ruan et al. showed that c-Rel together with p65, NFAT, CREB and SMAD forms an enhansosome to initiate Foxp3 transcription from the proximal promoter (43). How different extracellular signals affect the chromatin structure of the various Foxp3 regulatory elements, and how signals cooperate and integrate for chromatin remodeling and Foxp3 gene expression remain largely unknown. Here, we demonstrated that the two independent pathways of IL-6/IL-6R/STAT3 and PGN/TLR2/Myd88/IRF-1 resulted in inhibition or ablation of Foxp3 expression in aTreg and nTreg. These pathways caused profoundly different changes in the structure of Foxp3 chromatin, with subsequent effects on T cell fate and function. Our previous studies on IL-6 induced re-methylation CpG DNA at the upstream enhancer (2) and the present results suggest that depending on the stimulus and ligands, the natural history of inflammatory events may be marked by more or less inhibition of Treg mediated suppression, and subsequent transient or sustained interference with suppression. Understanding of the plasticity of Treg under different inflammatory conditions and the associated mechanisms of plasticity may be crucial for developing better strategies for Treg immune therapy to induce transplantation tolerance and prevent autoimmune diseases. Our study also provides mechanisms to enhance the efficacy of vaccines by selectively engaging IL-6 or IRF1 signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Alexander Rudensky, Julie Bander, Maria Abreu and Tadatsugu Taniguchi for reagents. This work was supported by NIH grants AI41428 and AI62765, and JDRF 1-2005-16 (all to JSB).

Abbreviations

- AcH3

acetylated histone 3

- aTreg

adaptive regulatory T cells

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

- IRF1

interferon regulatory factor 1

- IRF-E

IRF1 response elements

- Myd88

myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- nTreg

natural regulatory CD4 T cell

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supplemental Data: Supporting information will be hosted by publisher (Wiley-Blackwell) server.

References

- 1.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Plasticity of CD4(+) FoxP3(+) T cells. Current opinion in immunology. 2009;21(3):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger EP, et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, Penaranda C, Martinez-Llordella M, Ashby M, et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nature immunology. 2009;10(9):1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Q, Adams JY, Penaranda C, Melli K, Piaggio E, Sgouroudis E, et al. Central role of defective interleukin-2 production in the triggering of islet autoimmune destruction. Immunity. 2008;28(5):687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Regulatory T-cell functions are subverted and converted owing to attenuated Foxp3 expression. Nature. 2007;445(7129):766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature05479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang XO, Nurieva R, Martinez GJ, Kang HS, Chung Y, Pappu BP, et al. Molecular antagonism and plasticity of regulatory and inflammatory T cell programs. Immunity. 2008;29(1):44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science (New York, NY) 2003;299(5609):1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1078231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samanta A, Li B, Song X, Bembas K, Zhang G, Katsumata M, et al. TGF-beta and IL-6 signals modulate chromatin binding and promoter occupancy by acetylated FOXP3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):14023–14027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806726105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dardalhon V, Awasthi A, Kwon H, Galileos G, Gao W, Sobel RA, et al. IL-4 inhibits TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-beta, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(−) effector T cells. Nature immunology. 2008;9(12):1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/ni.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang JH, Kim YJ, Han SH, Kang CY. IFN-gamma-STAT1 signal regulates the differentiation of inducible Treg: Potential role for ROS-mediated apoptosis. European journal of immunology. 2009;39(5):1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Maren WW, Jacobs JF, de Vries IJ, Nierkens S, Adema GJ. Toll-like receptor signalling on Tregs: to suppress or not to suppress? Immunology. 2008;124(4):445–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Toll-dependent selection of microbial antigens for presentation by dendritic cells. Nature. 2006;440(7085):808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature04596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM. Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;458(7234):78–82. doi: 10.1038/nature07781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Ahmed E, Wang T, Wang Y, Ochando J, Chong AS, et al. TLR signals promote IL-6/IL-17-dependent transplant rejection. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6217–6225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Komai-Koma M, Xu D, Liew FY. Toll-like receptor 2 signaling modulates the functions of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(18):7048–7053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601554103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, Davidson TS, Huter EN, Shevach EM. Engagement of TLR2 does not reverse the suppressor function of mouse regulatory T cells, but promotes their survival. J Immunol. 2009;183(7):4458–4466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaRosa DF, Gelman AE, Rahman AH, Zhang J, Turka LA, Walsh PT. CpG DNA inhibits CD4+CD25+ Treg suppression through direct MyD88-dependent costimulation of effector CD4+ T cells. Immunology letters. 2007;108(2):183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komai-Koma M, Jones L, Ogg GS, Xu D, Liew FY. TLR2 is expressed on activated T cells as a costimulatory receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(9):3029–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400171101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutmuller RP, den Brok MH, Kramer M, Bennink EJ, Toonen LW, Kullberg BJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 controls expansion and function of regulatory T cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116(2):485–494. doi: 10.1172/JCI25439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberg HH, Ly TT, Ussat S, Meyer T, Kabelitz D, Wesch D. Differential but direct abolishment of human regulatory T cell suppressive capacity by various TLR2 ligands. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4733–4740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanin-Zhorov A, Cahalon L, Tal G, Margalit R, Lider O, Cohen IR. Heat shock protein 60 enhances CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell function via innate TLR2 signaling. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116(7):2022–2032. doi: 10.1172/JCI28423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Manicassamy S, Ravindran R, Deng J, Oluoch H, Denning TL, Kasturi SP, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent induction of vitamin A-metabolizing enzymes in dendritic cells promotes T regulatory responses and inhibits autoimmunity. Nature medicine. 2009;15(4):401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kano S, Sato K, Morishita Y, Vollstedt S, Kim S, Bishop K, et al. The contribution of transcription factor IRF1 to the interferon-gamma-interleukin 12 signaling axis and TH1 versus TH-17 differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(1):34–41. doi: 10.1038/ni1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7090):235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang JH, Kim YJ, Han SH, Kang CY. IFN-gamma-STAT1 signal regulates the differentiation of inducible Treg: potential role for ROS-mediated apoptosis. European journal of immunology. 2009;39(5):1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caretto D, Katzman SD, Villarino AV, Gallo E, Abbas AK. Cutting edge: the Th1 response inhibits the generation of peripheral regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):30–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negishi H, Fujita Y, Yanai H, Sakaguchi S, Ouyang X, Shinohara M, et al. Evidence for licensing of IFN-gamma-induced IFN regulatory factor 1 transcription factor by MyD88 in Toll-like receptor-dependent gene induction program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(41):15136–15141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607181103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liljeroos M, Vuolteenaho R, Rounioja S, Henriques-Normark B, Hallman M, Ojaniemi M. Bacterial ligand of TLR2 signals Stat activation via induction of IRF1/2 and interferon-alpha production. Cell Signal. 2008;20(10):1873–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fragale A, Gabriele L, Stellacci E, Borghi P, Perrotti E, Ilari R, et al. IFN regulatory factor-1 negatively regulates CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell differentiation by repressing Foxp3 expression. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):1673–1682. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tone Y, Furuuchi K, Kojima Y, Tykocinski ML, Greene MI, Tone M. Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nature immunology. 2008;9(2):194–202. doi: 10.1038/ni1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valencia X, Stephens G, Goldbach-Mansky R, Wilson M, Shevach EM, Lipsky PE. TNF downmodulates the function of human CD4+CD25hi T-regulatory cells. Blood. 2006;108(1):253–261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463(7282):808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitoh A, Ono M, Naoe Y, Ohkura N, Yamaguchi T, Yaguchi H, et al. Indispensable role of the Runx1-Cbfbeta transcription complex for in vivo-suppressive function of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2009;31(4):609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbalat R, Lau L, Locksley RM, Barton GM. Toll-like receptor 2 on inflammatory monocytes induces type I interferon in response to viral but not bacterial ligands. Nature immunology. 2009;10(11):1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/ni.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uematsu S, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. J Mol Med. 2006;84(9):712–725. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang JY, Nan X, Jin MS, Youn SJ, Ryu YH, Mah S, et al. Recognition of lipopeptide patterns by Toll-like receptor 2-Toll-like receptor 6 heterodimer. Immunity. 31(6):873–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Nunez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007;27(4):549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huber S, Schrader J, Fritz G, Presser K, Schmitt S, Waisman A, et al. P38 MAP kinase signaling is required for the conversion of CD4+CD25- T cells into iTreg. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coccia EM, Stellacci E, Marziali G, Weiss G, Battistini A. IFN-gamma and IL-4 differently regulate inducible NO synthase gene expression through IRF-1 modulation. International immunology. 2000;12(7):977–985. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchhoff S, Oumard A, Nourbakhsh M, Levi BZ, Hauser H. Interplay between repressing and activating domains defines the transcriptional activity of IRF-1. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS. 2000;267(23):6753–6761. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elser B, Lohoff M, Kock S, Giaisi M, Kirchhoff S, Krammer PH, et al. IFN-gamma represses IL-4 expression via IRF-1 and IRF-2. Immunity. 2002;17(6):703–712. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lal G, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic mechanisms of regulation of Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2009;114(18):3727–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruan Q, Kameswaran V, Tone Y, Li L, Liou HC, Greene MI, et al. Development of Foxp3(+) regulatory t cells is driven by the c-Rel enhanceosome. Immunity. 2009;31(6):932–940. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.