Abstract

Despite prompts from the field of family therapy since its inception, contemporary infant mental health theory and practice remain firmly rooted in and guided by dyadic-based models. Over the past 10 years, a groundswell of new empirical studies of triadic and family group dynamics during infancy have substantiated that which family theory has contended for decades: looking beyond mother-infant or father-infant dyads reveals a myriad of critically important socialization influences and dynamics that are missed altogether when relying on informant reports or dyad-based interactions. Such family-level dynamics emerge within months after infants are born, show coherence through time, and influence the social and emotional adjustment of children as early as the toddler and preschool years. This report summarizes key findings from the past decade of empirical family studies, highlights several areas in need of further conceptual development and empirical study by those who work with infants and their families, and outlines important implications of this body of work for all practicing infant mental health professionals.

The intentionally facetious title of this article was coined to cast a clear and unyielding spotlight on a paradox inherent in contemporary infant mental health (IMH) practice. Most infants around the world are, in fact, acculturated for substantial portions of their formative years in relationship systems where they have more than one significant caregiver and socialization agent. Yet infant mental health practice remains predominantly the bastion of dyadic, mother-infant relationship models and interventions. The aim of this article is to present both theoretical and empirical justification for a broader, family-based approach to all clinical work with infants and young children. Such an approach need not supplant or diminish the utility and efficacy of dyadic-based approaches, but it is vital for maximizing the contextual sensitivity and strengthening the maintenance of benefit of services rendered to mothers and infants.

The notion that each family’s full functional caregiving and socialization network needs to be considered in any infant mental health assessment is neither new nor particularly revolutionary. Practicing mental health workers have acknowledged the significance of family group contexts for nearly a century (Richmond, 1917), with clearly articulated theoretical stances advocated by family therapists since the 1950s. Triangular relations have also been central in many schools of psychoanalytic thought (Abelin, 1971; Atkins, 1984; Barrows, 2004; Britton, 2002; Chiland, 1982; Daws, 1999; Greenspan, 1982). Yet despite these historical realities, altering the face of current infant mental health practice so as to routinely incorporate a full family perspective in diagnostic assessments, consultations, and interventions would indeed be nothing short of revolutionary. Why this massive disconnect between extant theory and standard of practice in our field?

Perhaps the most compelling and essential reason, of course, is the sheer radiance, reach, and ubiquity of mother-infant bonds. Mothers bear children, are overwhelmingly (though not universally) the ones who nurse them upon their arrival, and in the final analysis are the ones held responsible by most cultures for whether their children live or die (Stern, 1995; McHale & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 1999). The dominant theory in infant mental health and indeed, in all psychological accounts of socioemotional development, remains the dyadically based attachment perspective (Ainsworth & Marvin, 1995; Bowlby, 1988; Sroufe, Carlson, & Levy, 2003); a paradigm bolstered further with each passing year by empirical investigations documenting increasingly compelling biological, cognitive, and emotional corollaries of attachment behavior and security (Fonagy, 2003). Further, both theoretical arguments and case evidence supporting the efficacy of dyadically based mother-infant relationship therapies have been argued convincingly within the infant mental health literature over the past 10 years (McDonough, 2004; Robert-Tissot, Cramer, & Stern, 1996; Stern, 1995; 2004).

These things said, the infant mental health literature, in general, and this journal, in particular, have not insulated themselves from important advances that challenge and contextualize dyadically based models. Indeed, our field has provided significant leadership in promoting scholarship on triads and families, beginning with the 1994 collaborative effort, “The dynamics of interfaces,” which featured the efforts of seven different scholars to understand from varying theoretical frames a triadic encounter between mother, father, and infant (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1994). Important studies on triadic representations and interactions have appeared in these pages and, more sparingly, in other influential developmental journals in the years since. For a while, it also appeared that the first revision of the DC:0–3 might include a family axis, broadly conceived (see Emde & Wise, 2003), though in the end this important development did not materialize. Indeed, in the final analysis we remain far from the collective epistemological change hinted at in writings from a decade ago (e.g., Pierrehumbert & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 1994; McHale & Cowan, 1996). A great number of important and fertile seeds have been sown, but the next moves need to be those of infant mental health professionals themselves.

In the following sections, the most central and critical conceptual distinctions between dyadic and multiperson levels of analysis and understanding are summarized, followed by a review of recent relevant work on the determinants and sequelea of family group dynamics. In closing, a final section identifies major implications of this work for the theory and practice of infant mental health.

BEYOND MOTHER-CHILD, FATHER-CHILD, AND HUSBAND-WIFE RELATIONSHIP DYNAMICS

Mental health professionals trained as family therapists have long been indoctrinated to appreciate that family units of three or more individuals are characterized by powerful relationship structures and dynamics not readily estimable from information about constituting monadic or dyadic subsystems. Indeed, this is perhaps the fundamental tenet of virtually all systemic frameworks (Cox & Paley, 2003). Perhaps surprisingly then, a historical look back at our field’s leading outlets for child development research reveals that it was not until an influential position piece by Patricia Minuchin (1985) decrying that “studies of the parent-child dyad…do not represent the child’s significant reality, especially after infancy” (p. 296) that family group perspectives truly began shaping the research efforts of child developmentalists. Studies of infant and child socialization that undertook a family group level of analysis were almost altogether absent from the peer-reviewed, published literature through that point.

Minuchin’s conceptual position did far more than just remind developmental scientists of the relevance of fathers in promoting their children’s social and emotional adaptation or of the widespread negative impact of destructive background marital conflict – clinicians knew, and know, that father engagement and marital distress are central considerations in understanding the adjustment of children and families. Rather, her paper redirected attention to the foundational principle that unique and distinctive social experiences are afforded whenever relationship dynamics triangulate beyond just the child and an “other” (Bowen, 1972; Cobb, 1996). An important corollary of this position, later developed in detail by Cummings and Davies (1996) (Davies, Cummings, & Winter, 2004; see also Byng-Hall, 1986; McHale, 1997) is that the perceived cohesiveness of the full family unit, as much as any single caregiver-child dyad, is what ultimately serves as the young child’s central locus of security or insecurity.

This distinction between families as a collective unit, guided by two or more coparenting architects working in tandem or in opposition, and families as a collection of dyadic relationships distinct unto themselves but also exerting mutual influence on one another (Hinde & Stevenson-Hinde, 1988), is a critically important one and the crux of this article. It is a contrast illustrated well by an examination of publications from the fathering research boom of the 1980s. A curiosity of this period was the sheer number of studies that sought to establish how fathers could be as competent parents as mothers, or to document unique influences fathers could have in children’s lives. Seldom embraced was the reality that parenting by both mothers and fathers has joint and mutual effects in the same family. Setting aside a dyadic model of “the infant and the other” (Winnicott, 2002) to view early experience as collectively organized by a coparenting team demands that the questions we ask about child socialization and acculturation shift. The emphasis becomes one of consistency between, rather than within, parenting adults.

What is the Essence of Coparenting?

Coparenting, as I use the term here and elsewhere, is an enterprise set upon by those mutually responsible for the care and upbringing of a child. However, it decidedly does not pertain simply or even primarily to the sharing of child care labor, which many authors who write about modern families do emphasize (Ehrensaft, 1987; Fish, New, & VanCleave, 1992; Hattery, 2001; Perry-Jenkins, Pierce, & Goldberg, 2004). For even in the multitude of families across the globe where fathers shoulder virtually none of the day-to-day care of their infants and young children, most men nonetheless do have a profound developmental influence in the lives of their children. Such influence—just as with the influence of children’s mothers—needs to be seen and understood within the context of the parental strivings of each responsible adult within the child’s family.

If coparenting is not concerned principally with caregiving, then what is at the concept’s center? The notion of coparenting that has guided the work summarized in this article is more consonant with the Ehrenberg, Gearing-Smll, & Hunter, 2001 conceptualization of “shared parenting.” It draws most directly from Salvador Minuchin’s, 1974 theory of family structure and notion of the family’s “executive subsystem,” viewing coparenting as concerned principally with the degree of collaboration, affirmation, and support between adults raising children for whom they share responsibility. Coparenting alliances function effectively when these individuals collaborate to provide a family context that communicates to children solidarity between the parenting figures, a consistent and predictable set of rules and standards (regardless of whether the child lives in a single household or in multiple ones), and a safe and secure home base (McHale, Khazan, Erera, Rotman, DeCourcey, & McConnell, 2002).

Evaluating Coparenting Dynamics

Family therapy practice has brought together family groups for the purpose of assessment and evaluation for the past half century, with one-way mirrors and direct observation now indispensable tools of the trade. Surprisingly, however, the studied use of observational approaches to systematically document and chart coparental patterns and dynamics within nuclear family systems is only a very recent advance in the fields of infant and child development. It was not until the late 1980s when Fivaz-Depeursinge and colleagues in Lausanne, Switzerland (later working with a handful of collaborating sites throughout Europe and the United States), Belsky and colleagues, then at Pennsylvania State University, and McHale and colleagues, then at the University of California at Berkeley, began systematically observing and charting early coparenting and family alliance patterns. The early published work of these investigators (e.g., Belsky, Crnic, & Gable, 1995; Corboz-Warnery, Fivaz-Depeursinge, & Bettens, 1993; Fivaz-Depeursinge, Corboz-Warnery, & Frascarolo, 1996; McHale, 1995) converged in establishing several features of observable triadic process that distinguished among families of infant and toddler-aged children. Central among these were patterns of competitiveness, verbal sparring, and active interference amongst the coparents; differences in the degree to which both coparents were mutually involved and engaged with the baby; variability in levels of warmth, cooperation, and positivity connecting all three members of the family triangle; and differences in the extent to which the flow of family interactions were infant or child (as opposed to adult) driven.

Rated systematically by clinical observers, these dimensions can be examined in tandem to identify distinctive subgroupings of families in studies on infant and toddler-aged children. Two research groups in particular have empirically studied and outlined such typologies. In their longitudinal study of clinical and community families studied prospectively from early infancy, Fivaz-Depeursinge and Corboz-Warnery (1999) documented four distinctive family alliance patterns which they conceived of as disordered, collusive, stressed, and cooperative. These alliances, detected clinically from the patterning and flow of body postures and affective signaling during an innovative semistructured diagnostic assessment called the Lausanne Trilogue Play (LTP), can be distinguished from one another along dimensions including the quality of participation by the various members of the family triad (inadequate in disordered alliances, antagonistic in collusive alliances) and by the affective connection among members of the unit (difficult to sustain in all but cooperative alliances).

Studying a community sample of families of older 21/2 year olds, McHale, Lauretti, Talbot, and Pouquette (2002) evaluated families along dimensions including discrepancies in parental engagement, coparental antagonism, cohesion and harmony, and child (versus adult) centeredness, and identified five distinct family types. Child-at-center families were those in which the toddler was the fulcrum of all attention and activity; the child’s interests and initiatives drove the family interaction, parents engaged with the child but not with each other, and neither antagonism nor warmth and cooperation between coparents were much in evidence. Among competitive coparenting families, both parents were likewise quite engaged with the child, but interactions were steered by adult, not child, preferences and initiatives, antagonism between parents was pronounced, and warmth and cooperation were typically absent. Cohesive child-centered families and cohesive parent-in-charge families were similar in that both families demonstrated warm and cooperative connections between adults, mutual parental engagement with the toddler, and an absence of antagonistic interactions. The primary difference was that in cohesive child-centered families, children’s initiatives guided the interaction while in the cohesive parent-in-charge families, adults largely set the tone and structure and steered the interaction. Finally, in excluding families, marked discrepancies were noted in the two parents’ levels of engagement with the child, so much so that one parent could be described as disengaged. In such families, neither coparental antagonism nor warmth and cooperation were prominent family features.

The fact that distinctive family group patterns can be ascertained during infancy and toddlerhood would be of little more than academic interest were it not for findings from several research teams including Fivaz’s (e.g., Fivaz-Depeursinge, 2003; Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1996), ours (e.g., McHale, Kazali, Rotman, Talbot, Carleton, & Lieberson, 2004; McHale, 2007), and those of other clinicians using observational methodologies to study early coparental processes within families (Feldman, Weller, Siroda, & Eidelman, 2003; Feldman, Weller, & Sirota, 2003; von Klitzing, Simoni, Amsler, & Burgin, 1999) verifying not only that distinctive sets of coparenting dynamics can be documented in families of infants as young as three months of age, but also that such dynamics show marked stability through time (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1996; Gable, Belsky, & Crnic, 1995; McHale & Rotman, 2007; Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, & Frosch, 2004).

Given the very early stage at which identifiable coparental structures and dynamics begin consolidating, and the coherence that coparental solidarity shows from the early postpartum onward, there is value in cataloguing that which is known about the family systems in which these coparental and family processes begin taking shape. The next section summarizes major research findings on coparenting and triadic family dynamics that have emerged during the past decade. I focus in this review principally on studies that capitalized on observational means for documenting triadic and family group dynamics, as observation is an indispensable component of any diagnostic assessment in clinical contacts with families around coparenting issues.

MAJOR RESEARCH FINDINGS FROM THE FIRST DECADE OF COPARENTING RESEARCH

Early Coparenting Difficulties Are Linked to Marital Adjustment

There are several replicated findings that have now been quite firmly established. Perhaps the most robust of these is that clear linkages exist between marital distress and observed coparenting dynamics (Cowan & Cowan, 1987; Katz & Low, 2004; Kitzmann, 2000; Lewis, Owen, & Cox, 1988). Couples who are more distressed in their marriages behave more antagonistically during their coparental interactions – especially when engaging with their young sons (Belsky et al., 1995; McHale, 1995; Katz & Gottman, 1996). They show more pronounced parenting discrepancies, or imbalances in levels of parental involvement, with some evidence suggesting that greater discrepancies may be especially evident when their child is a daughter (Ablow, 1997; McHale, 1995), and that family interactions of maritally distressed couples are reliably characterized by low levels of warmth, cohesion, and harmony with both sons and daughters (Brody & Flor, 1996; Frosch, Mangelsdorf, & McHale, 1998; McHale, 1995; McHale, Johnson, & Sinclair, 1999; McHale et al., 2004).

A second, related finding of critical importance is that marital distress manifested before the baby even arrives on the scene (that is, during the pregnancy) predicts later miscoordination and lack of mutuality in the family’s triadic process. This is true whether the observational evaluation of the triadic family process occurs during the early postpartum months (McHale et al., 2004; McHale, 2007); at the end of the baby’s first year (Diamond, Heinicke, & Mintz, 1996; Lewis et al., 1988); during the toddler years (Paley, Cox, Kanoy, Harter, Burchinal & Margand, 2005); and even as distant as four years postpartum (Lindahl, Clements, & Markman, 1997). This finding appears to be a robust one and, as will be developed further below, is of considerable importance from a preventive standpoint.

Early Coparenting Difficulties Are Shaped by Parents’ Intrapsychic Experience

Although early coparenting dynamics are shaped by and build upon the couple’s established capacities for negotiation and problem solving in their marital relationship, triadic dynamics are also far more complex than marital dynamics and do not simply replicate them. Beyond husband-wife power and relationship dynamics, formidable intrapsychic structures guide each partner’s expectations about triadic relatedness, and these intrapsychic forces also contribute significantly to the process of becoming a triad.

Some of the most exciting and innovative work in this area over the past decade has been that of von Klitzing and colleagues, who report that parents’ prenatal “triadic capacities,” or propensity to reflect upon the future family as a threesome rather than as self and infant, foreshadow the quality of later triadic coordination during family interactions at four months postpartum. In a similar vein, McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, and colleagues (2004) established that significant expressions of pessimism in men and women’s prebirth representations of the future coparental alliance and future family process likewise foreshadow a less harmonious triadic process at three months postpartum, and Fivaz-Depeursinge and colleagues (Carneiro, Corboz-Warnery, & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 2006; Favez, Frascarolo, Carneiro, Montfort, Corboz-Warnery, & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 2006), experimenting with a prebirth variant of the LTP in which they asked expectant parents to role play their first encounter with their new baby, established that warmer, more collaborative role plays by the coparental team also foreshadowed better coordinated family alliances at four months postpartum. These findings indicate that representations maintained by expectant parents influence future coparental and triadic processes during the initial months of new parenthood.

Early Coparental Adjustment Predicts Later Coparental Adjustment

The prognostic value of these prenatal assessments is particularly meaningful given the evidence cited earlier that early coparenting and family group dynamics, once established, show surprising coherence through time even through periods of significant developmental change (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1996; Gable et al., 1995; McHale & Rotman, 2007; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004). Such coherence in coparenting structure and dynamics may not at first blush seem especially surprising or even significant, to the extent that these dynamics are created from, supported, and maintained by parents’ individual family representations and relational solidarity. Yet the fact that stable family structures begin consolidating within 100 days after the baby’s arrival, and show coherence well on into the child’s toddler years, may be one of the more remarkable discoveries in the burgeoning infant-family field. The significance of stability through time may be of greatest credence to infant mental health professionals because indicators of distress in the coparental alliance as early as the child’s first year predict later problems in adjustment for the children up to three years down the road (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1996; Frosch, Mangelsdorf, & McHale, 2000; McHale & Rasmussen, 1998). These findings will be discussed in greater detail shortly.

Parent Strengths Can Protect Coparenting Even in the Face of Marital Distress

Beyond parents’ personally held belief systems about their partners and about wished-for family process and functioning, other intrapsychic characteristics and mechanisms also help determine the evolution of coparental patterns in families. In some cases, these characteristics serve as resources to help override the strong, but not inevitable, link between marital distress and coparental problems. For example, in work with families of 12-month-olds, Talbot & McHale (2004) found that the link between problems in the marriage and low coparental solidarity was attenuated when fathers showed greater flexibility and self-restraint. The notion that men without a “quick switch” can help prevent marital discontent from negatively coloring the coparental and family group dynamic is an unusual one for helping professionals, in that it is one of the few findings in the empirical literature identifying men’s capacities as a potential therapeutic resource.

It is important to underscore here that the finding is in respect to men’s personality characteristics, not men’s family engagement. High father engagement, almost universally acknowledged as an asset for infants and families, can actually catalyze or amplify competitive and antagonistic coparental dynamics in maritally distressed families. Hence, the issue for interventionists is seldom as straightforward as simply getting fathers more involved.

Coparenting Difficulties Place Young Children at Risk

Although we are still far short of a groundswell of replicated research documenting the specific effects of coparental antagonism, disengagement, or lack of harmony and cohesion on young children’s development, a number of studies provide evidence that early coparenting problems should be of concern to us. Thus far, high levels of coparental antagonism and/or lack of coparental mutuality and cohesion in families observed during infancy or the early preschool years, have been tied in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies to clinically significant symptomatology on the Child Behavior Checklist (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 1996); to high frequencies of parent, daycaregiver, and teacher-reported aggressive behavior and internalizing problems (McHale & Rasmussen, 1998; Schoppe, Mangelsdorf, & Frosch, 2001); to gravitation over time (from infancy to toddlerhood) toward greater disinhibition (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996); to an increased likelihood of insecure attachments (Frosch et al., 2000); and to more aggressive imagery during semistructured family doll play (McHale, Neugebauer, Asch, & Schwartz, 1999). Moreover, associations linking coparental and family process to infant, toddler, and child adjustment remain pronounced even after taking into account contributions of mother-infant, father-infant, and marital functioning (Belsky et al., 1996; Katz & Low, 2004; McHale, Kuersten, & Lauretti, 1996; McHale & Rasmussen, 1998; McHale, Johnson, & Sinclair, 1999).

Infants Are Active Partners in the Process of Triadification

Given these findings, buttressed by prospective studies linking prenatal factors to family dynamics and child adjustment months and years down the road, it is quite tempting to restrict our focus on ways in which coparental dynamics shapes children’s development. However, the process of becoming a threesome, which Emde, 1994 has labeled “triadification,” is always a three-person enterprise. An emerging imperative for those engaged in infant-family work is to begin casting a much closer eye on the baby’s role (McHale, Kavanaugh, & Berkman, 2003). Contributions are probably most readily understood and conceptualized at a molar or macro level, as when an infant’s easy or difficult temperament deflects otherwise expectable family trajectories leading from pregnancy to the postpartum period (McHale, Kazali, et al., 2004). However, they also can and must be seen and understood microgenetically, as when infants’ own behavioral maneuvers facilitate or disrupt triadic processes involving their mothers and fathers.

As one illustration, Fivaz-Depeursinge, Favez, and Lavanchy (2005) have presented empirical evidence revealing the infant’s early capacity for triangulation, arguing that this capacity provides support for primary intersubjectivity. Fivaz and colleagues’ LTP observations revealed that infants as young as three and four months already engage reciprocally with their two parents simultaneously, and that individual infants differ markedly in their propensity to make triangular bids. Perhaps most significantly, their propensity can be tied to observed coordination in the family during trilogue play. These observations provide compelling substantiation for that which most professionals know well: young children work very hard to sustain family homeostasis. Remarkably, however, Fivaz’s observations reveal that children’s contributions begin taking hold even earlier than most developmentalists had imagined (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 2005; Fivaz-Depeursinge & Favez, 2006).

Dissonance and Development

Before concluding this review, it is important to comment on the nature of the observational evidence that family researchers have relied upon when evaluating miscoordination during family interactions. Our clinical antennae are typically attuned to subtle microevents involving disrupted behavioral sequences, gaze interruptions, disordered body postures, and other forms of poorly coordinated and mismatched communication (Fivaz-Depeursinge & Corboz-Warnery, 1999; McHale & Alberts, 2003). It should go without saying, however, that we must always be thinking about poor coordination and active dissonance on multiple fronts. On the one hand, we cannot ignore findings such as those reported earlier: infant facilitation with triangulation is related to levels of coordination/miscoordination observed in the triad even during the first half of the baby’s first year. Longitudinal studies also clearly document worrisome longer-term effects of chronic miscoordination, intrusiveness, and antagonism observed between parents in disrupting toddler regulation and facility with peer adjustment.

At the same time, the theme of dissonance driving development runs throughout developmental theory (Tronick & Gianino, 1986; Werner & Kaplan, 1963). Interactional repair of negative affective communications affords critical opportunities for growth (Tronick & Weinberg, 1997), and negative affect regulation is important for normal development (Emde, 1992). Hence, an important ongoing task for clinical infant researchers who work with families is tracking families’ immediate and longer-term adaptations when they demonstrate difficulty coordinating together, toward specifying the circumstances under which coparental dissonance is generative and growth promoting, and circumstances in which it is problematic and growth stultifying. Until such a roadmap has been charted, it is incumbent upon clinicians to view any information obtained during evaluations of the family triad or group that signal coparental dissonance solely as hypothesis generating, rather than as diagnostic.

The full range of developmental sequelae of distressed coparental and family alliances has yet to be established; most research to date has focused only broadly on internalizing or externalizing problems among toddlers and preschoolers. To the extent that family group processes do possess the uniquely powerful socializing influences they are posited to hold, these adjustment indicators are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg. For those family systems where clinical assessments of coparental antagonism and dissonance accurately capture a core family theme that itself is maintained or that intensifies over time, any number of important regulatory and other adaptive functions may be affected among children from such families. It is possible to speculate that among these would be disruptions of moral development, including the internalization of rule governed behavior; precocious or disrupted capacities for the self-regulation of emotion and hypervigilant attunement to emotional signaling; relationship representations colored by anticipation of antagonism and animosity; and in certain cases, a paralysis of initiative or inability to act decisively under times of psychosocial stress (McHale, Talbot, Grugan, & Reisler, 2007; Hirshberg, 1990).

Summary: The First Decade of Coparenting Research

In summary, coparenting dynamics are not simply marital conflict or insecure attachments in disguise. Coparental and family group process is a distinctive feature of families, both built upon the psychodynamics and relationship functioning of the parenting adults but also distinct from, and transcending, those relationships. Infants themselves contribute significantly to the establishment and maintenance of triadic family patterns and their contributions must be attuned to during therapeutic interventions with families. Limited evidence also indicates that spillover from marital to coparenting systems may be attenuated in families where a parent possesses the capacity for self-restraint and resilience under times of stress. Early coparental and triadic patterns foreshadow later adjustment, lawfully and prospectively predict subsequent child adaptation, and help to explain the emergence of child difficulties even when assessments of dyadic parent-child relationship systems do not reveal any marked sources of concern. Unchecked, problematic coparental and family alliances have the potential to prompt a host of adjustment difficulties for children as young as toddler and preschool age, and hence the assessment of family group dynamics stands as a critically important component of all clinical evaluations completed with families of infants and young children.

EMERGING ISSUES DEMANDING CONCEPTUAL AND EMPIRICAL ATTENTION

Coparenting Multiple Children

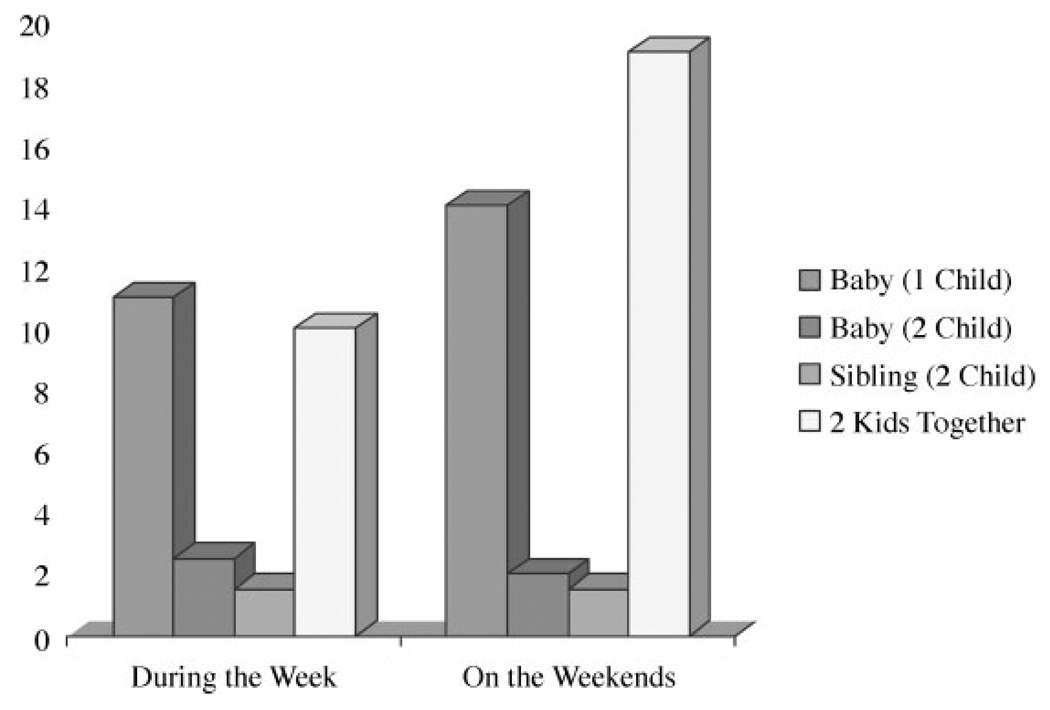

Despite the significant advances in our base of empirical knowledge about family level dynamics during infancy, virtually all published studies of coparenting in nuclear families to date have involved two parents and a single child. This is unfortunate, both because most children grow up in families with at least one sibling, and because the family experiences of first- and second-born experiences within a family triad are markedly different from one another. In a recent project, we asked 125 families with 12-month-old infants to keep a weekly diary record of the number of hours the two parents spent together—either at home or on the go—with the baby. In 75 of the 125 families, the baby was the first born while in the remaining 50 families, the baby had an older (preschool-aged) brother or sister. For the latter families, we also asked the adults to track the number of hours they spent (as a couple) alone with the older child, and the number of hours they spent as a couple together with the two children. As can be seen from Figure 1, the opportunities for triadic experiences among second-born 12-month-olds are far fewer than they are for first-born 12-month-olds. For the first born, prior to the second child’s arrival, there is always and only a triad, and there are interesting grounds to speculate that this remains a governing unconscious wish for first borns even after the arrival of new siblings. For the second born, by contrast, there is always a tetrad. Our conceptual models through the first decade of coparenting and family group research have often failed to take this reality into consideration; to date, we remain a field dominated by studies of nuclear two-parent families with just one child, a relative rarity worldwide.

FIGURE 1.

Average number of hours (per week) couples report spending together with their 12-month-old children and the babies’ preschool-aged siblings.

This leads to two related points. The first is that with very few exceptions (e.g., Kreppner, Paulsen, & Schuetze, 1982; Volling & Elins, 1998), empirical studies have taught us very little to date about whether siblings are coparented similarly, or whether systematic differences are seen in coparenting processes as they often are in parenting behavior. In one of the few controlled studies on this topic, McConnell, Khazan, Lauretti, and McHale (2003; 2007 submitted) compared parents’ mutual engagement with first-born preschoolers and second-born 12-month-old siblings during tetradic family group interactions. Their findings revealed that the coparental partners as a team displayed greater mutual supervision of the first born than of the second born, were warmer and more cooperative during their joint interactions with the older child, and were more directive (and less child centered) with the first born. Lest it seem that these findings may owe to the different developmental stages of the two siblings rather than to birth order per se, McConnell and colleagues found, quite intriguingly, that the finding concerning greater mutual oversight of, and directiveness with, first borns replicated when they compared coparental behavior of first-born 12-month-olds and second-born 12-month-olds during triadic interactions, with the older sibling absent. These observations indicate that the stance the parenting team takes toward different children in the same family can be quite different, signifying further that coparental dynamics must always be understood with reference to the particular child being coparented. Much more work is needed in this area over the next decade to advance our clinical understanding of coparenting and family group process in systems with multiple children.

Coparenting in Diverse Family Systems

The second related point pertinent to our field’s overreliance on studies of Western nuclear family systems with two parents and a single child is that we presently know precious little about the effects of coparenting solidarity or divisiveness in most other kinds of family systems and networks. The literature to date on this topic was first summarized by McHale, Khazan, and colleagues (2002), and since that time, several new studies and initiatives have been launched to assess the relevance of the coparenting construct in a variety of cultural groups and family systems. As we cautioned in 2002, however, it will remain critical that work proceeding from this frame be guided by emic approaches and carried out by indigenous scholars. Constructs founded in one culture and imported mindlessly into another are likely to be of limited value at best, and to be altogether misguided at worst.

This said, there is beginning evidence that cocaregiver solidarity or divisiveness may have pertinence in North American multigenerational family systems where children are raised by mothers and maternal grandmothers (Apfel & Seitz, 1996; Brody, Flor, & Neubaum, 1998; Chase-Lansdale, Gordon, & Coley, 1999; Goodman & Silverstein, 2002), and this line of evidence is likely to expand significantly within the next decade. Important comparative studies signifying the role and relevance of cocaregiving dynamics within Middle Eastern and Asian families have also begun to make their way into the peer-reviewed literature (Feldman, Masalha, & Nadam, 2001; Kurrien & Vo, 2004; McHale, Rao, & Krasnow, 2000) and promise to advance this field exponentially.

Practice Implications

Perhaps the most pressing need for joint and collaborative efforts by infant mental health professionals over the next decade is on steps needed to allow practitioners to responsibly evaluate families and make good use of this emerging knowledge base. Beyond the wealth of knowledge that the family therapy field has provided over the past half century (Nichols & Schwartz, 1998), pioneering efforts by Fivaz-Depeursinge, Corboz-Warnery, and Keren (2004), expanding on McDonough’s (1993; 2004) interaction guidance work, have provided the explicit beginnings of a paradigm for family systems-driven interventions with families. A number of important questions are now in need of focused attention, including one of perennial debate among family therapies: will it be sufficient to devote our attentions principally to altering enacted family process in order to affect meaningful change in coparental systems, or must each co-caregiver’s individually held family representations also be a target of direct intervention? Data indicating that men’s and women’s perspectives on early coparenting may take different developmental routes (Van Egeren, 2004) would suggest the latter.

Addressing these questions should be a collective endeavor. To the extent that all those working with infants and families make efforts to collaboratively draw upon the existing infant-family knowledge base reviewed here, employ pertinent assessment paradigms in their own clinical work, and make concerted efforts to publish and disseminate their findings from both case studies and from more controlled clinical trials, we will be able to advance the field in necessary ways over the coming decade. Our collective aim should be to point toward another World Association for Infant Mental Health (WAIMH) plenary on family group dynamics ten years from now, one that will be in a position to make a case for “best practices” by drawing on findings from relevant clinical and research inquiries that have been contributed by IMH professionals worldwide.

FOR NOW: MAJOR IMPLICATIONS OF FAMILY RESEARCH FOR PRACTICING IMH PROFESSIONALS

Though we remain a distance away from being able to advocate best practices in the diagnosis and treatment of coparenting and family difficulties during infancy, there are nonetheless several major advisories that can be drawn from the first decade of empirical research on this topic.

First, and most centrally, it is time at long last for assessments of the family to actually involve assessments of the family. We have relied too long and unthinkingly on reports about family functioning provided by a single caregiver (almost always mothers), on dyadic assessments of mothers with infants, and occasionally (but separately) on dyadic assessments of fathers with infants. This is not sufficient. Only through observing coparents together with the baby within the context of the family as an interacting group can the absence of an esprit de corps, tendencies toward interference and undermining, or patterns of exclusion and disengagement, be diagnosed. Such family patterns cannot be reliably estimated through other means and are critically important to understand given their contemporaneous and prospective linkages with infant and child maladjustment. Indeed, during North American field trainings for the new DC 0–3R over a year after the 2004 World Congress, toddlers in each of the two training cases presented by the late Robert Harmon showed meaningful improvements only after their significant caregiving figures (a mother and father in one case; parents and an auxiliary family caregiver in the other) began programmatically coordinating their caregiving interventions.

Yet nowhere in the DC: 0–3R are clinicians guided to systematically document evidence of cocaregiver solidarity or dissonance. They are invited to make note of “marital conflict,” as an Axis IV “Challenge to child’s primary support group” (#11 – Marital discord), though as I have outlined, marital conflict is a very different construct from coparenting. As a prelude to Axis IV, clinicians are advised that “the caregiving environment may shield and protect the child from the stressor…compound the impact by failing to offer protection…or reinforce the impact through the effect of anxiety (p. 55).” What is missing is that the cocaregiving environment may actually introduce a source of stress for the infant. Altering practice to routinely include coparenting assessments would begin to introduce the paradigmatic change hinted at a decade ago. Those of us “in the trenches” know well how often fathers or other resident caregivers are excluded from clinic or home visits that engage mothers and babies—as well as from the conceptual frameworks underpinning these bedrock early interventions—even when these individuals are physically present and available in the home during the visit.

At the same time, family group assessments cannot, and decidedly should not, substitute for dyadic ones. In a revealing study reported by Lauretti and McHale (1997); (2009), information from both dyadic and family group contexts was needed to provide the clearest picture of family dynamics. In distressed families, maternal sensitivity and paternal engagement, which had appeared adequate in dyadic assessments, declined significantly within the family group context, whereas in nondistressed families, greater cross-contextual continuity was evinced. Incorporating the understanding afforded by observations such as these into clinical conceptualizations of the infant’s caregiving environment can dramatically enhance the relevance of treatment approaches with the family. Dyad-based assessments remain indispensable as well because in a great many families, any difficulties of coordination observed within the coparental unit are likely to pale in comparison to significant pathology or dysfunction inherent in the parenting of one or more of the baby’s caregivers. In such families, the individual parent and the dyadic subsystem of caregiver and baby will always need intensive care and repair. It seems likely that assessments of the coparental process will prove most useful in families devoid of severe abuse and neglect (though see Katz & Low, 2004), and that such assessments may provide insights as to why a child whose parents appear “good enough” during dyadic assessments is nonetheless encountering significant adjustment difficulties.

The evidence reviewed here would also seem to demand that impressions concerning coparental dynamics be conceptualized within the family’s relevant cultural or subcultural contexts, and within the context of other information that the clinician has obtained concerning the coparents views of their coparenting alliance. There are several points to be made here. First, continued research with the Lausanne Trilogue Play and other family assessment paradigms are likely to reveal distinctive patterns of affect and engagement within different cultural groups (see, e.g., Feldman & Masalha, 1999; reviewed in McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, et al., 2004). Normative patterns of paternal and grandmaternal engagement with infants and young children also vary widely both between and within cultural groups (Kurrien & Vo, 2004; Sudarkasa, 1999). Hence, the dominant cultural reference group must necessarily provide the relevant background context for any clinical understanding of families’ microprocesses. Second, it is rapidly becoming difficult to talk about a family’s cultural context in the singular; multirace families have been growing exponentially in North America and we know precious little to date on the day-to-day coparenting challenges and adjustments of bicultural families or of the ramifications of their adaptations for infant and child development. Third, observations of interactions, while powerful and unique, cannot always reveal significant structural problems in the family, and hence an appreciation of each parent’s own views about their coparental partnership and difficulties is indispensable for an adequate diagnostic assessment of the coparenting unit’s strengths and difficulties.

A fourth implication of this work derives from the strong link that has been established between marital and coparenting dynamics. Given the extent to which coparental difficulties appear to be borne of (McHale, Kazali, et al., 2004; Van Egeren, 2004), and intensify marital difficulties (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004), it may be possible to improve coparental functioning by treating marital problems. At the same time, however, it seems possible and even likely that coparenting adults may be more willing to engage clinically around issues that concern the health and well being of their children than around marital problems. Hence, there would be particular value in controlled intervention studies that designed, examined, and compared family functioning following marital interventions and following interventions focused explicitly on coparenting but that targeted marital communication and consensus building secondarily (Cowan, Cowan, Ablow, Johnson, & Measelle, 2005; Feinberg, 2003; see also McHale, 2007).

A fifth, cautionary implication is that the benefits for coparenting that may follow from strengthening marital relationships should not necessarily be expected when intervening with other dyadic subsystems. This may be the least commonsensical point of this article, but perhaps the most important. A recent thrust in the mother-infant intervention literature has been on choice of therapeutic targets and ports of entry (Sameroff, 2004) most effective for families at specific points in time. Stern (2004) has made the lucid argument that when intervening in the mother-infant dyadic system, it does not matter very much which point of entry is chosen and privileged; techniques used to affect change will vary, but end results are likely to be similar since the whole system will be changed. The same does not necessarily follow for multiperson systems of three or more individuals, however. Focusing principally on altering mother-infant, or father-infant, relations has as much potential to trigger negative ripple effects within family systems (such as coparental antagonism and competition) as it does positive effects.

The emotional exclusion and jealousy felt by many men following transitions to parenthood has been well chronicled (Hyman, 1995; Waletzky, 1979), but women too can respond negatively when other caregivers intrude significantly into the parenting realm (McHale & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 1999). In a thoughtful conceptual piece, Dienhart & Daly (1997) contended that only when mothers are able to manage ambivalence and affirm fathers’ parenting roles will coparental alliances function effectively; empirical work by Beitel & Parke (1998) and Bulanda (2004) has been consistent with this proposition. Relatedly, in family systems of new teen mothers where cocaregivers are maternal grandmothers rather than fathers, too much grandmaternal involvement with the new mothers’ first borns leads to the teenagers having second children in more rapid succession (Apfel & Seitz, 1996). The common and key point, once again, is that when the clinician’s organizing framework becomes that of the full family system rather than of a mother-infant dyad plus any auxiliary support figures, the kinds of questions asked during case conceptualization necessarily change. The reverberating effects of intervening with a parent-infant dyad in a triadic or larger family system must be carefully considered in all clinical work with families of infants and toddlers.

There are two final points that follow from research to date. First, findings indicating that early coparenting dynamics begin to take shape in ways that are anticipated by prenatal functioning, and that once established such dynamics remain remarkably stable through the toddler years, calls for greater attention to preventive efforts that target coparental functioning (Feinberg, 2002). How best to intervene preventively is an open question needing thoughtful and creative responses from clinicians and researchers alike, with the full engagement and collaboration of the medical community. What seems clear is that prenatal fantasies and representations about the family process (and not simply about the self-baby relationship) are prognostic of later adaptation, particularly when the expectancies of cocaregivers conflict (which they often do). Marital distress and communication difficulties, too, are strongly prognostic, and families at risk for coparental difficulties are strained further still when joined by a temperamentally difficult infant. During the early postpartum months, signs of family-wide distress can be detected both from talking to parents about their own and their partner’s adjustment to new parenthood and by observing the family engaged together as a threesome. Observed changes in sensitivity or engagement as parents move from interacting one on one with the baby to interacting within the family triad may be particularly important diagnostically. Educational efforts with the joint aims of strengthening coparental support and cooperation and short circuiting competitive strivings or propensities toward disengagement should be an explicit aim in healthcare contacts with families from pregnancy forward (Feinberg, 2002)

The final point pertinent to clinical diagnosis and intervention with coparenting and family systems is that clinically referred children as young as three can communicate (through semistructured doll play assessments) their own perceptions of the coparental and family alliance (Buchsbaum & Emde, 1990; McHale, Neugebauer, et al., 1999; Oppenheim, Emde, & Hasson (1997)). Even if clinicians were to do little more than reliably include in their assessments a standard assessment such as McHale, Neugebauer, and colleagues’ (1999) adaptation of Gerber and Kaswan’s (1971) Family Doll Placement Technique (in which children are asked to use a doll family to tell stories of happy, sad, and mad families), they would begin to reckon with the important ways that young children perceive their family and its dynamics. Even preschool children with significant communicative disorders can signal through structured doll play whether family discord is directed toward children or centered primarily within the adult-adult subsystem, and such information can be useful in conceptualizing and communicating about family dynamics in ways helpful to children. As with any projective data, such information can serve as hypothesis generating only, but to the extent possible children themselves should never be left out of evaluations of coparental and family group dynamics.

In conclusion, the time now seems ripe for infant mental health professionals to begin making a concerted effort to include conceptualizations of each family’s functional cocaregiving network and family group process in evaluations of infants and toddlers with adjustment difficulties. While such information will not prove to be of tremendous incremental value and clinical utility in all cases, they will in a great many others. Operating with a mindset that it is important to view other caregiving figures in families not as background or supportive context but as integral to an understanding of the family group dynamic will be central to this enterprise. Above all, our collective understanding of early socialization environments and of the ways in which such environments promote early infant and child adjustment will profit once our assessments of the family truly come to involve assessments of the family.

Footnotes

Paper presented at Decade of Behavior Distinguished Lecture, 2004, World Association for Infant Mental Health Congress, Melbourne, Australia.

REFERENCES

- Abelin E. The role of the father in the separation-individuation process. In: McDevitt J, Settlange C, editors. Separation-individuation. New York: International Universities Press; 1971. pp. 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ablow J. Marital conflict across family contexts: Does the presence of children make a difference?. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development; Washington, D.C. 1997. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M, Marvin R. On the shaping of attachment theory and research: An interview with Mary D.S. Ainsworth. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1995;60:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Apfel N, Seitz V. African American adolescent mothers, their families, and their daughters: A longitudinal perspective over twelve years. In: Leadbeater B, Way N, editors. Urban girls: Resisting stereotypes, creating identities. New York: New York University Press; 1996. pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins R. Transitive vitalization and its impact on father representation. Contemporary Psychoanalysis. 1984;20:663–676. [Google Scholar]

- Barrows P. Fathers and families: Locating the ghost in the nursery. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Beitel A, Parke R. Paternal involvement in infancy: The role of maternal and paternal attitudes. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:268–288. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development. In: McHale J, Cowan P, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. Family therapy and family group therapy. In: Kaplan H, Sadock B, editors. Group treatment of mental illness. New York: E.P. Dutton; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Britton R. Forever father’s daughter. In: Trowell J, Etchegoyen A, editors. The importance of fathers. Hove: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Flor D. Coparenting, family interactions, and competence among African American youth. In: McHale J, Cowan P, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Flor D, Neubaum E. Coparenting processes and child competence among rural African-American families. In: Lewis M, Feiring C, editors. Families, risk, and competence. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum S, Emde R. Play narratives in 36-month-old children: Early moral development and family relationships. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1990;45:129–155. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1990.11823514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda R. Paternal involvement with children: The influence of gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2004;66:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Byng-Hall J. Family scripts: A concept which can bridge child psychotherapy and family therapy thinking. Journal of Child Psychotherapy. 1986;12:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro C, Corboz-Warnery A, Fivaz-Depeursinge E. The prenatal Lausanne trilogue play: A new observational assessment tool of the prenatal co-parenting alliance. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:207–228. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale L, Gordon R, Coley R. Young African American multigenerational families in poverty: The contexts, exchanges, and processes of their lives. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with divorce, single parenting, and remarriage: A risk and resiliency perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Chiland C. A new look at fathers. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1982;37:367–379. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1982.11823371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C. Adolescent-parent attachments and family problem-solving styles. Family Process. 1996;35:57–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corboz-Warnery A, Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Bettens C. Systemic analysis of father-mother-baby interactions: The Lausanne triadic play. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1993;14:298–316. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan P, Cowan C. Couples relationships, parenting styles, and the child’s development at three. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development; Baltimore, MD. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan P, Cowan C, Ablow J, Johnson V, Measelle J. The family context of parenting in children’s adaptation to elementary school. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Paley B. Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings M, Davies P. Emotional security as a regulatory process in normal development and the development of psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology. 1996;8:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Davies P, Cummings M, Winter M. Pathways between profiles of family functioning, child security in the interparental subsystem, and child psychological problems. Development & Psychopathology. 2004;16:525–550. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daws D. Parent-infant psychotherapy: Remembering the Oedipus complex. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 1999;19:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond D, Heinicke C, Mintz J. Separation-individuation as a family transactional process in the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996;17:24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dienhart A, Daly K. Men and women cocreating father involvement in a nongenerative culture. In: Hawkins A, Dollahite D, editors. Generative fathering: Beyond deficit perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg M, Gearing-Smll M, Hunter M. Childcare task division and shared parenting attitudes in dual-earner families with young children. Family relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2001;50:143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft D. Parenting together. New York: Free Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Emde R. The infant’s relationship experience: Developmental and affective aspects. In: Sameroff A, Emde R, editors. Relationship disturbances in early childhood: A developmental approach. New York: Basic Books; 1992. pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Emde R. Commentary: Triadification experiences and a bold new direction for infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1994;15:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Emde R, Wise B. The cup is half full: Initial clinical trials of DC 0–3 and a recommendation for revision. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Favez N, Frascarolo F, Carneiro C, Montfort V, Corboz-Warnery A, Fivaz-Depeursinge E. The development of the family alliance from pregnancy to toddlerhood and children outcomes at 18 months. Infant and Child Development. 2006;15:59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M. Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: A framework for prevention. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:173–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1019695015110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science & Practice. 2003;3:95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Masalha S. Patterns of interaction in Israeli and Arab families at the transition to parenthood: Traditional systems at periods of change. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Masalha S, Nadam R. Cultural perspective on work and family: Dual-earner Israeli Jewish and Arab families at the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:492–509. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Weller A, Sirota L. Testing a family intervention hypothesis: The contribution of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care) to family interaction, proximity, and touch. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:94–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish LS, New RS, VanCleave NJ. Shared parenting in dual-income families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62:83–92. doi: 10.1037/h0079306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E. L’alliance coparentale et le développement affectif de l’enfant dans le triangle primaire (Coparental alliance and infant affective development in the primary triangle) Therapie Familiale. 2003;24:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Corboz-Warnery A. The primary triangle: A developmental systems view of mothers, fathers, and infants. New York: Basic Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Corboz-Warnery A, Frascarolo F. Assessing the triadic alliance between fathers, mothers, and infants at play. In: McHale J, Cowan P, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 27–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Corboz-Warnery A, Keren M. The primary triangle: Treating infants in their families. In: Sameroff A, McDonough S, Rosenblum K, editors. Treating parent-infant relationship problems: Strategies for intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Favez N. Exploring triangulation in infancy: Two contrasted cases. Family Process. 2006;45:3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Favez N, Lavanchy C. Four-month-olds make triangular bids to father and mother during trilogue play with still-face. Social Development. 2005;14:361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge E, Stern D, Bürgin D, Byng-Hall J, Corboz-Warnery A, Lamour M, et al. The dynamics of interfaces: Seven authors in search of encounters across levels of description of an event involving a mother, father, and baby. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1994;15:69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P. The development of psychopathology from infancy to adulthood: The mysterious unfolding of disturbance in time. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:212–239. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch C, Mangelsdorf S, McHale J. Correlates of marital behavior at 6 months postpartum. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1438–1449. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch C, Mangelsdorf S, McHale JL. Marital behavior and the security of preschooler-parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:144–161. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Belsky J, Crnic K. Coparenting during the child’s 2nd year: A descriptive account. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1995;57:609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber G, Kaswan J. Expression of emotion through family grouping schemata, distance, and interpersonal focus. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1971;36:370–377. doi: 10.1037/h0031108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C, Silverstein M. Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Family structure and well-being in culturally diverse families. Gerontologist. 2002;42:676–689. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan S. The “second other”: The role of the father in early personality formation and the dyadic-phallic phase of development. In: Cath S, Gurwitt A, Ross J, editors. Father and child: Developmental and clinical perspectives. Boston: Little Brown; 1982. pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hattery A. Tag-team parenting: Costs and benefits of utilizing nonoverlapping shift work in families with young children. Families in Society. 2001;82:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hinde R, Stevenson-Hinde J. Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford: Oxford Science; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshberg L. When infants look to their parents: II. Twelve-month-olds’ response to conflicting parental emotional signals. Child Development. 1990;61:1187–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman J. Shifting patterns of fathering in the first year of life: On intimacy between fathers and their babies. In: Shapiro J, Diamond M, editors. Becoming a father: Contemporary, social, developmental, and clinical perspectives. New York: Springer; 1995. pp. 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Gottman J. Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. In: McHale J, Cowan P, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 57–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Low S. Marital violence, co-parenting, and family-level processes in relation to children’s adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:372–382. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann K. Effects of marital conflict on subsequent triadic family interactions and parenting. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:3–13. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppner K, Paulsen S, Schuetze Y. Infant and family development: From triads to tetrads. Human Development. 1982;25:373–391. doi: 10.1159/000272821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurrien R, Vo ED. Who’s in charge?: Coparenting in south and southeast Asian families. Journal of Adult Development. 2004;11:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lauretti A, McHale J. Shifting patterns of parenting styles between dyadic and family settings: The role of marital quality. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development; Washington D.C. 1997. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Lauretti A, McHale J. Shifting patterns of parenting styles between dyadic and family settings: The role of marital distress. In: Russo M, De Luca A, editors. Psychology of Family Relationships. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Owen M, Cox M. The transition to parenthood: III. Incorporation of the child into the family. Family Process. 1988;27:411–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1988.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl K, Clements M, Markman H. Predicting marital and parent functioning in dyads and triads: A longitudinal investigation of marital processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:139–151. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M, Khazan I, Lauretti A, McHale J. Time to expand: Studying coparenting in families with multiple children. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development; Tampa, FL. 2003. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M, Lauretti A, Khazan I, McHale J. Coparenting in families with multiple children: The roles of birth order, family context, and sibling status. 2007 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough S. Interaction guidance: Understanding and treating early infant-caregiver relationship disturbances. In: Zeanah C, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough S. Interaction guidance: Promoting and nurturing the caregiving relationship. In: Sameroff A, McDonough S, Rosenblum K, editors. Treating parent-infant relationship problems: Strategies for intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J. Co-parenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:985–996. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J. Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process. 1997;36:183–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J. Charting the bumpy road of coparenthood. Washington, DC: Zero to Three Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Alberts A. Thinking three: Coparenting and family-level considerations for infant mental health professionals. The Signal. 2003;11:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Cowan P. New Directions for Child Development. Vol. 74. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Fivaz-Depeursinge E. Understanding triadic and family group process during infancy and early childhood. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:107–127. doi: 10.1023/a:1021847714749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Johnson D, Sinclair R. Family-level dynamics, preschoolers’ family representations, and playground adjustment. Early Education and Development. 1999;10:373–401. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Kavanaugh K, Berkman J. Sensitivity to infants’ signals: As much a mandate for family researchers as for parents. In: Booth A, Crouter A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Kazali C, Rotman T, Talbot J, Carleton M, Lieberson R. The transition to co-parenthood: Parents’ pre-birth expectations and early coparental adjustment at three months post-partum. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:711–733. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Khazan I, Erera P, Rotman T, DeCourcey W, McConnell M. Coparenting in diverse family systems. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 75–107. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Kuersten R, Lauretti A. New directions in the study of family-level dynamics during infancy and early childhood. In: McHale J, Cowan P, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. Vol. 74. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. New Directions for Child Development; 1996. pp. 5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Kuersten-Hogan R, Rao N. Growing points in the study of coparenting relationships. Journal of Adult Development. 2004;11:221–235. doi: 10.1023/B:JADE.0000035629.29960.ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Lauretti A, Talbot J, Pouquette C. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of coparenting and family group process. In: McHale J, Grolnick W, editors. Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 127–165. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Neugebauer A, Radin A, Schwartz A. Preschoolers’ characterizations of multiple family relationships during family doll play. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:256–268. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Rao N, Krasnow A. Constructing family climates: Chinese mothers’ reports of their coparenting behavior and preschoolers’ adaptation. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Rasmussen J. Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:39–58. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Rotman T. Is seeing believing? Expectant parents’ outlooks on coparenting and later coparenting solidarity. Infant Behavior & Development. 2007;30:63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Talbot J, Grugan P, Reisler S. Recalled coparenting conflict, paralysis of initiative, and sensitivity to conflict during adolescence. 2007 doi: 10.26502/fjwhd.2644-28840022. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development. 1985;56:289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families & family therapy. Oxford, England: Harvard U. Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M, Schwartz R. Family therapy: Concepts and methods. 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim D, Emde R, Hasson M. Preschoolers face moral dilemmas: A longitudinal study of acknowledging and resolving internal conflict. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 1997;78:943–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Pierce C, Goldberg A. Discourses on diapers and dirty laundry: Family communication about child care and housework. In: Vangelisti A, editor. Handbook of family communication. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 541–561. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert B, Fivaz-Depeursinge E. From dyadic to triadic relational prototypes. In: Vyt A, Bloch H, editors. Early child development in the French tradition: Contributions from current research. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond M. Social diagnosis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Tissot C, Cramer B, Stern D. Outcome evaluation in brief mother-infant psychotherapies: Report on 75 cases. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996;17:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. Ports of entry and the dynamics of mother-infant interventions. In: Sameroff A, McDonough S, Rosenblum K, editors. Treating parent-infant relationship problems: Strategies for intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe S, Mangelsdorf S, Frosch C. Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers’ externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:526–545. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan S, Mangelsdorf S, Frosch C. Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:194–207. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Carlson E, Levy A. Implications of attachment theory for developmental psychopathology. In: Hertzig M, Farber E, editors. Annual progress in child psychiatry and child development: 2000–2001. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. The motherhood constellation: A unified view of parent-infant psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. The motherhood constellation: Therapeutic approaches to early relational problems. In: Sameroff A, McDonough S, Rosenblum K, editors. Treating parent-infant relationship problems: Strategies for intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sudarkasa N. Interpreting the African heritage in Afro-American family organization. In: Koontz S, editor. American families. New York: Routledge; 1999. pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot J, McHale J. Individual parental personality traits moderate the relationship between marital and coparenting quality. Journal of Adult Development. 2004;11:191–205. doi: 10.1023/B:JADE.0000035627.26870.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronick E, Gianino A. Interactive mismatch and repair: Challenges to the coping infant. Zero to Three. 1986;6:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick E, Weinberg M. Depressed mothers and infants: Failure to form dyadic states of consciousness. In: Murray L, Cooper P, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 54–81. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren L. The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:453–477. [Google Scholar]

- Volling B, Elins J. Family relationships and children’s emotional adjustment as correlates of maternal and parternal differential treatment: A replication with toddler and preschool siblings. Child Development. 1998;69:1640–1656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Klitzing K, Simoni H, Amsler F. The role of the father in early family interactions. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1999;20:222–237. [Google Scholar]

- Waletzky L. Husbands’ problems with breast-feeding. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1979;49:349–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1979.tb02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H, Kaplan B. Symbol formation. Oxford: Wiley; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott D. Winnicott on the child. Cambridge, MA: Perseus; 2002. [Google Scholar]