Abstract

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) is widely expressed in brain tissue including neurons, glia, and endothelia in neurovascular units. It is a major source of oxidants in the post-ischemic brain and significantly contributes to ischemic brain damage. Inflammation occurs after brain ischemia and is known to be associated with post-ischemic oxidative stress. Post-ischemic inflammation also causes progressive brain injury. In this study we investigated the role of NOX2 in post-ischemic cerebral inflammation using a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model in mice. We demonstrate that mice with NOX2 subunit gp91phox knockout (gp91 KO) showed 35–44% less brain infarction at 1 and 3 days of reperfusion compared with wild-type (WT) mice. Minocycline further reduced brain damage in the gp91 KO mice at 3 days of reperfusion. The gp91 KO mice exhibited less severe post-ischemic inflammation in the brain, as evidenced by reduced microglial activation and decreased upregulation of inflammation mediators, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α, inducible nitric oxide synthases, CC-chemokine ligand 2, and CC-chemokine ligand 3. Finally, we demonstrated that an intraventricular injection of IL-1β enhanced ischemia- and reperfusion-mediated brain damage in the WT mice (double the infarction volume), whereas, it failed to aggravate brain infarction in the gp91 KO mice. Taken together, these results demonstrate the involvement of NOX2 in post-ischemic neuroinflammation and that NOX2 inhibition provides neuroprotection against inflammatory cytokine-mediated brain damage.

Keywords: NOX; Focal ischemia; Neuroinflammation; Microglia, IL-1β; gp91phox

Introduction

Stroke ranks third among all causes of death in the US and it is the most common cause of severe morbidity (AHA statistics 2010 http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1265665152970DS-3241%20HeartStrokeUpdate_2010.pdf). Transient ischemic stroke is characterized by initial ischemia in the brain, followed by reperfusion. Various pathophysiological processes occur during stroke and they contribute to brain damage in a temporal manner. Shortly after ischemia, because of the insufficient supply of oxygen and glucose, cells rapidly develop energy failure and membrane depolarization, and are unable to maintain intracellular ion homeostasis, which may result in cell damage (Lipton, 1999). Substantial amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in the brain as early as at 1 h of reperfusion (Murakami et al., 1998). ROS-mediated oxidative stress significantly induces further damage in the ischemic brain (Chan, 1996, 2001).

ROS were robustly generated by pro-oxidant enzyme activity and by mitochondria after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) (Chan, 2001). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) is an important pro-oxidant protein in the brain (Bedard and Krause, 2007). It catalyzes the generation of superoxide anions (O2•−), which are major precursors of ROS (Bedard and Krause, 2007). gp91phox is the catalytic subunit of NOX2, and gp91phox knockout (gp91 KO) mice, which are deficient in NOX2 activity, have been produced (Pollock et al., 1995). Our previous study demonstrated that gp91phox ablation significantly alleviated ROS generation and lipid and DNA oxidative damage after cerebral ischemia (Chen et al., 2009).

After stroke, brain damage continues in the penumbra region and usually takes several days to mature (Lipton, 1999). It has been postulated that the delayed brain damage may be due to the cerebral inflammation process that occurs in response to the initial ischemic brain insult (Barone and Feuerstein, 1999; Wang et al., 2007). Cerebral inflammation is characterized by microglia activation, peripheral monocytes, and neutrophil infiltration and the upregulation of inflammatory mediators including cytokines and chemokines (Wang et al., 2007). Microglia are the main immune cells in the brain, and play a central role in cerebral inflammation. Besides acting as macrophages by scavenging cell debris, microglia are also involved in the inflammatory process by generating inflammation factors, presenting and processing antigens, and augmenting the immune response (Block et al., 2007; Garden and Möller, 2006; Stoll et al., 1998). It has been widely reported that both ROS and the inflammation process result in neuronal death after I/R. However, the interaction between post-ischemic cerebral inflammation and oxidant stress, especially the role of the pro-oxidant enzyme NOX2 in post-ischemic inflammation, is not well understood.

We and others have reported that NOX2 ablation reduces oxidative stress and brain damage at 1 day of reperfusion after cerebral ischemia (Chen et al., 2009; Walder et al., 1997). In this study, we investigated the role of NOX2 in post-ischemic inflammation, including activation of microglia and gene transcription of inflammation factors. We also studied the role of NOX2 in interleukin-1β (IL-1β) -mediated brain damage by directly injecting IL-1β into the cerebral ventricle.

Material and Methods

Animal preparation

The gp91 KO mice were produced by Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were characterized by Pollock et al. (1995). There were no observable phenotypic differences between the gp91 KO and wild-type (WT) mice. The genotype of each mouse was determined by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of DNA from tail biopsies. Male mice, 12–16 weeks old (25–30 g), were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane for induction and 1.0% isoflurane vaporized in N2O and O2 (3:2) for maintenance. Rectal temperatures were monitored and maintained at 37.0°C ± 0.5°C with a homeothermic blanket control unit (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) and a heating lamp.

Mouse focal cerebral ischemia models

Focal cerebral ischemia was induced in mice by occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (MCAO) using a 6-0 coated suture as described previously (Chen et al., 2009). Briefly, the left common carotid artery was exposed. The external carotid artery was dissected distally and coagulated along with the terminal lingual and maxillary artery branches. The internal carotid artery was isolated and a coated suture (6–0 monofilament nylon) was introduced into the external carotid artery lumen through an incision and then gently advanced approximately 9–9.5 mm in the internal carotid artery lumen to block MCA blood flow. A successful occlusion was indicated by a decrease in regional cerebral blood flow to less than 20% of the baseline (data not shown). Except as specified, mice were subjected to 60 min of MCAO, and cerebral blood flow was restored by suture withdrawal. The incision was closed and the mice underwent recovery under a heating lamp. After recovery, the animals were returned to their cages with free access to food and water. Preliminary studies were carried out using various doses of minocycline and an optimal dose was chosen. For minocycline treatment, 40 mg/kg minocycline (diluted in 0.25 ml phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were administered by intraperitoneal injection 5 min after suture withdrawal. The reperfusion group was administered 20 mg/kg minocycline twice daily on the second and third days until sacrifice. Apocynin, a NOX2 inhibitor, was administered by intraperitoneal injection (4 mg/kg body weight) 5 min before suture withdrawal. Our previous study showed that low-dose apocynin treatment reduces I/R-mediated cerebral infarction by 50% (Chen et al., 2009). A total of 129 mice were operated on in this study. Fifteen mice died during surgery or perfusion and were excluded. All animal procedures used in this study were conducted in strict compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

IL-1β intracerebroventricular injection

Mice were anesthetized and placed in a stereotactic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). After drilling a small hole in the left parietal bone (0.1 mm posterior to bregma and 0.9 mm lateral from midline), a Hamilton syringe (Reno, NV) was lowered 3.1 mm below the brain surface. Two doses of IL-1β (2.5 ng in 4 μl PBS each) (Sigma-Aldrich) or the vehicle (PBS) were injected into the ventricle 30 min before MCAO and 10 min after reperfusion. After the procedure, the mice were allowed to recover and were returned to their cages. Our preliminary study showed no significant mortality from the vehicle injection.

Measurement of infarct volume

After 24 and 72 h of reperfusion, the mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane vaporized in N2O and O2 (3:2) and then decapitated. Coronal sections were cut into 2-mm slices using a mouse brain matrix (Zivic Instruments, Pittsburgh, PA) and they were immediately immersed in 2% 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 20 min. The infarction area in each section was calculated with NIH image analysis software. The infarct areas of each slice were separately summed and multiplied by the interval thickness to obtain infarct volumes as described before (Chen et al., 2009).

Western blotting

Whole-cell fractions were obtained from the entire MCA territory (ischemic side and non-ischemic side). Tissues were lysed by lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), followed by 30 sec of sonication at 4°C with an ultrasonic processor (VC 130 PB; Sonic & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT). Protein concentration was determined by a bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of samples (10 μG) were loaded per lane. The samples were then electrophoretically separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate gels and the resolved proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The primary antibodies were an anti-α-spectrin antibody (1:8000; Millipore, Billerica, MA), an anti-IBA-1 (ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1) antibody (1:1000; WAKO, Richmond, VA), an anti-IL-1β antibody (1:600; Biolegend, San Diego, CA), anti-3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) (1:1000; Millipore, Billerica, MA), and an anti-β-actin antibody (1:20,000; Sigma-Aldrich). Western blotting was performed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) with the use of enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Quantitative expression of the proteins was analyzed by scanning the films of the blots and calculating the intensity as measured by Bio-Rad Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Immunohistological staining

For immunohistochemistry after focal ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion, the mice were transcardially perfused with heparin in saline (2 IU/L), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PBS. The brains were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and subsequently cryoprotected with 20% sucrose and 30% sucrose overnight. Brains were cut into coronal sections (30 μm) on a freezing microtome (SM 2000R; Leica, Nussloch, Germany). Two coronal sections (0.98 mm anterior and 1.06 mm posterior to the bregma) were selected and processed for immunohistological staining. Sections were probed with an antibody against IBA-1 (1:400; WAKO). The sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-goat IgG (1:400; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and avidin-peroxidase (1:100; Vector Laboratories). Color reaction was developed with a diaminobenzidine kit (Vector Laboratories). For negative control, a consecutive section was treated with similar procedures, except that the primary antibody was omitted. Images were observed and captured with a Zeiss optical microscope (Axioplan2, Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

RNA preparation and cDNA reverse transcription

The animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane at 24 h and 3 days of reperfusion. After decapitation, the brains were quickly removed and the MCA territory was obtained. Extraction of total RNA was performed using a Purelink kit (Invitrogen) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer. The RNA concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm in a spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized from the RNA product using an RT2 First Strand kit (Invitrogen) and a PCR machine.

Quantitative real-time PCR

All quantitative real-time PCRs (QPCRs) were carried out using the Mx3000 PCR System (Stratagene). QPCR amplifications were performed using the recommended buffer supplied by the manufacturer. The QPCR mixture consisted of 1 μl of each template, 1 μl of PCR primer pair (10 μM), and 12.5 μl QuantiTect SYBR Green including ROX as an internal control. The primer mixture of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (CCL3), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and 18s ribosomal RNA was purchased from Invitrogen. The 18s ribosomal RNA gene was used as a housekeeper gene control. For the QPCR cycling conditions, we followed the manufacturer's instructions, with modifications. For every QPCR assay, a dissociation curve was also run as a quality control. Data analysis was performed using Mx3000 software (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). CTs were determined using the signal/noise ratio set to standard deviation above background-subtracted mean fluorescence values.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparison between groups was achieved with ANOVA using the Fisher PLSD test. Significance was accepted at p < 0.05 (StatView Adept Scientific Inc., Acton, MA).

Results

NOX2 and minocycline synergistically reduced ischemic brain damage

We investigated the role of microglia and inflammation progression in ischemic brain injury using gp91 KO mice and minocycline, a known inhibitor of microglia activation (Yrjänheikki et al., 1999). Infarction volume was assessed in WT mice, gp91 KO mice, minocycline-treated WT mice, and minocycline-treated gp91 KO mice after focal ischemia and reperfusion. After 75 min of focal ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion, the average infarction volume in the WT mice was 50 ± 4.5 mm3. This was decreased to 28.5 mm3 and 23.4 mm3 in the gp91 KO and minocycline-treated mice, respectively, suggesting the role of free radicals and microglia activation in ischemic brain damage (Fig. 1). Minocycline treatment further reduced brain infarction in the gp91 KO mice, however, it did not reach a statistical difference (17 ± 1.0 mm3, p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). As the brain infarction progressed during reperfusion, we studied it at 3 days of reperfusion. In the WT animals, infarction volume increased to approximately 86 mm3. NOX2 ablation or minocycline treatment conferred brain protection and reduced brain infarction volume by approximately 35% (55–57 mm3, p < 0.05 compared with WT mice) (Fig. 1). Moreover, minocycline treatment further protected the gp91 KO mice against ischemia insult, as those mice had the smallest brain infarction (21 ± 2.3 mm3, p < 0.05 compared with the gp91 KO mice or the WT mice treated with minocycline) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Decreased brain infarct volume after I/R in mice with NOX2 inhibition or minocycline treatment. Infarct volume at 24 or 72 h of reperfusion after MCAO in WT mice, gp91 KO mice, minocycline-treated WT mice (Mino), and minocycline-treated KO mice (Mino+KO) (#p < 0.05 vs. WT mice at 24 h of reperfusion, *p < 0.05 vs. WT mice at 72 h of reperfusion, **p < 0.05 vs. gp91 KO or minocycline-treated mice at 72 h of reperfusion) (n = 3–5).

gp91 ablation ameliorated cleaved spectrin and protein nitration after I/R

Cleaved spectrin causes cytoskeleton disruption and is a strong indication of cell death (Büki et al., 2000). Genetic ablation of gp91 or pharmacological inhibition of NOX2 reduces cleaved spectrin at early reperfusion time points (3 and 24 h) (Chen et al., 2009). We further examined cleaved spectrin at 3 days of reperfusion after ischemia. A large amount of the cleaved spectrin product was detected by Western blot in the ischemic hemisphere. The ratio of spectrin density (ipsilateral/contralateral) in the WT mice was approximately 2:1, which is significantly higher than in the gp91 KO mice (1.6 ± 0.2, p < 0.05; Fig. 2). Therefore, NOX2 inhibition protects brain tissue against ischemic damage.

Fig. 2.

Cleaved spectrin in WT and gp91 KO mice. (A) Western blot analysis of cleaved spectrin at 3 days of reperfusion. Significant cleaved spectrin products were detected in the WT mice, but not in the gp91 KO mice. Con, contralateral; Ipsi, ipsilateral. (B) Summarized data from panel A. *p < 0.05 vs. WT cleaved spectrin (150 kDa). Summarized data are presented as a ratio of (cleaved spectrin: ipsilateral/contralateral)/(uncleaved spectrin: ipsilateral/contralateral) (n = 4–5).

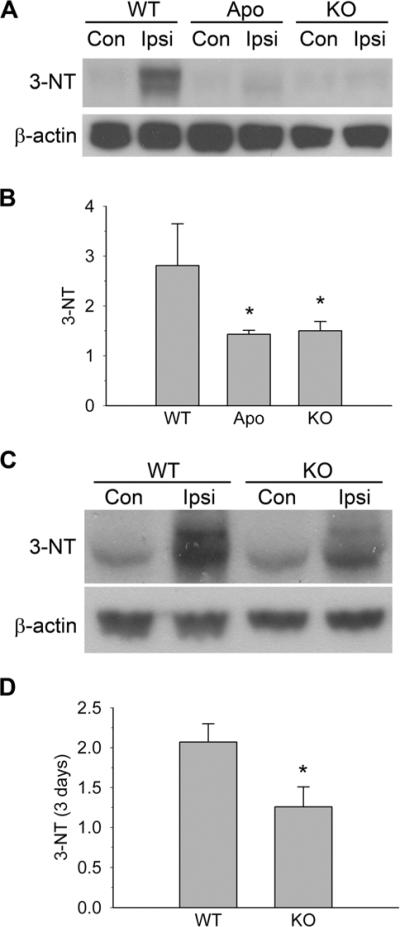

Robust oxidants are generated after cerebral I/R and cause significant DNA and lipid oxidation and tissue injury (Chen et al., 2009). We further investigated protein nitration during I/R using the biomarker 3-NT. A minimal amount of 3-NT expression was identified on the contralateral side of the brains. At 24 h of reperfusion, 3-NT expression increased by approximately 2.8-fold in the WT ipsilateral hemisphere, which indicates protein nitration. In the ischemic hemisphere, 3-NT overexpression in the WT mice was significantly greater than that in the KO mice and apocynin-treated mice (2.8 ± 0.8 vs. 1.5 ± 0.2 and 1.4 ± 0.1, p < 0.01; Fig. 3A and 3B). At 3 days of reperfusion, 3-NT was upregulated by 2.1-fold in the ipsilateral hemisphere of the WT mice, which is still significantly higher than that in the gp91 KO mice (~1.3-fold, p < 0.05; Fig. 3C and 3D).

Fig. 3.

3-NT expression in WT, apocynin-treated (Apo), and gp91 KO mice. (A) Western blot analysis of 3-NT at 24 h of reperfusion. Significant 3-NT was detected in the WT mice, but not in the apocynin-treated or the gp91 KO mice. Con, contralateral; Ipsi, ipsilateral. (B) Summarized data from A. *p < 0.05 vs. WT mice. Summarized data are presented as a ratio of 3-NT/β-actin, which are normalized to the contralateral side. (C) Western blot analysis of cleaved 3-NT at 3 days of reperfusion. Genetic ablation of NOX2 inhibition reduced 3-NT upregulation. (D) Summarized data from C. *p < 0.05 vs. WT mice (n = 4–5).

NOX2 and microglia activation after I/R

Microglia play a crucial role in central nervous system inflammation response after cerebral ischemia. To further characterize the role of NOX2 in post-ischemic inflammation progression, we examined microglia using an IBA-1 antibody. As shown in Figure 4A and 4B, microglia on the contralateral side demonstrated ramified morphology after I/R. On the WT ipsilateral side, microglia processes retracted and the morphology changed from ramified to “amoebic,” which indicates microglia activation. This activation was less prominent in the KO mice after I/R, as more microglia still exhibited the ramified morphology (Fig. 4C and 4D).

Fig. 4.

NOX2 inhibition reduced microglia activation after I/R. At 24 h of reperfusion, more activated microglia were detected in the WT ipsilateral hemisphere than in the gp91 KO mice. (A) WT contralateral; (B) WT ipsilateral; (C) gp91 KO contralateral; (D) gp91 KO ipsilateral. Insets in A and B, magnification of one typical microglia. Inset in D, negative control. Scale bar = 50 μm. Images shown are representative of 4–5 experiments. (E) After I/R, microglia in KO ischemic side had more longer processes than in the WT ipsilateral hemisphere (*p < 0.05 vs. WT ipsilateral) (n = 4–5).

Activated amoebic microglia comprised shorter and retracted processes compared with ramified resting microglia. To better assess microglia activation, we measured the length of the microglia processes. On the contralateral side, the average length of microglia processes showed no significant difference between the WT and gp91 KO mice (33.4 ± 0.4 μm, 34.7 ± 1.5 μm, p > 0.05). After I/R, most microglia processes retracted and the average length was reduced by 52% in the WT ipsilateral hemisphere (16.3 ± 0.6 μm), and it was significantly shorter than that of the KO mice (25.4 ± 1.5 μm, p < 0.05).

IBA-1, a calcium binding protein, is specifically expressed in cultures of rat brain microglia (Ito et al., 1998). It is involved in RacGTPase-dependent membrane ruffling and phagocytosis (Kanazawa et al., 2002). We measured microglia-specific IBA-1 to assess the quantity of microglia. At 3 h of reperfusion, there was no difference in the IBA-1 level between the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of either the WT or KO mice (Fig. 5A and 5B). However, at 1 day of reperfusion after focal ischemia, the WT mice showed significant IBA-1 upregulation in the ipsilateral hemisphere (~1.5-fold increase compared with contralateral side) (Fig. 5C and 5D). In contrast, there was no significant upregulation in the gp91 KO mice (1.1 ± 0.1). Using the NOX2 inhibitor apocynin, I/R-mediated IBA-1 upregulation was also abolished (Fig. 5C and 5D). At 3 days of reperfusion, ischemic brain tissue in the WT mice still demonstrated a more pronounced IBA-1 upregulation compared with the gp91 KO mice (1.72 ± 0.23 vs. 1.13 ± 0.07, p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Changes in IBA-1 expression after cerebral I/R. (A), (C) and (E) Western blot analyses of IBA-1 expression after I/R. I/R induced IBA-1 upregulation at 1 and 3 days of reperfusion, but not at 3 h of reperfusion. Con, contralateral; Ipsi, ipsilateral. (B), (D) and (F) Summarized data from (A), (C) and (E), respectively. Numbers are presented as a ratio of IBA-1/β-actin, which are normalized to the contralateral side (*p < 0.05 vs. WT mice).

Post-ischemic inflammatory gene expression was attenuated in gp91 KO mice

Because microglia activation can cause the excretion of inflammation factors, including chemokines and cytokines, we next used gp91 KO mice to investigate whether NOX2 is needed for the upregulation of inflammation factor transcripts (including TNFα, CCL2, CCL3, and iNOS) after focal cerebral ischemia. At 1 day of reperfusion, MCAO upregulated TNFα at the mRNA level by 7–7.4 times in the WT and KO mice. The WT mice also showed a significantly greater increase in TNFα than the KO mice at 3 days of reperfusion (17.7 ± 2.3 vs. 9.0 ± 2.2, p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). NOX2 inhibition reduced iNOS upregulation at 3 days of reperfusion (4.0 ± 0.7 vs. 1.7 ± 0.4, p < 0.05), but not at 1 day (2.8 ± 0.5 vs. 2.5 ± 0.5, p > 0.05) (Fig. 6B). At 24 h of reperfusion, both the WT and KO mice showed a similar level of increase in CCL2 (41.5 ± 7.0 vs. 37.3 ± 11.6, p > 0.05). At 3 days of reperfusion, the WT mice had significantly more CCL2 upregulation than the KO mice (52.9 ± 8.8 vs. 26 ± 4.8; Fig. 6C). NOX2 inhibition reduced CCL3 upregulation as early as 1 day (49 ± 6.6 vs. 28 ± 8, p < 0.05) and continued to 3 days of reperfusion (48.6 ± 8.3 vs. 23 ± 4, p < 0.05; Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Inflammation factor gene transcription after cerebral ischemia in WT or gp91 KO mice. (A) gp91 ablation reduced upregulation of TNFα transcription at 3 days of reperfusion (n = 8–12). (B) gp91 ablation reduced upregulation of iNOS transcription at 3 days of reperfusion (n = 8–9). (C) gp91 ablation reduced upregulation of CCL2 transcription at 3 days of reperfusion (n = 8–9). (D) gp91 ablation reduced upregulation of CCL3 transcription at 1 and 3 days of reperfusion (n = 9–11) (*p < 0.05 vs. WT mice). Summarized data are presented as a ratio of ipsilateral side/contralateral side.

Genetic NOX2 ablation abolished IL-1 β-mediated brain damage

Among the inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β is an important inflammation factor known to be involved in ischemic cerebral damage. However, it is not clear whether NOX2 activation/inhibition affects IL-1β-mediated brain damage. We first examined IL-1β expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. The IL-1β RNA levels were increased to 20- and 8-fold in the WT and gp91 KO mice, respectively, at 1 day of reperfusion. At 3 days of reperfusion the IL-1β RNA level of upregulation was reduced in both the WT and gp91 KO mice (11.4-fold and 3.8-fold, respectively) (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the level of RNA change, Western blot results also demonstrated less IL-1β upregulation in the gp91 KO mice than in the WT mice at 3 days of reperfusion (Fig. 7B and 7C).

Fig. 7.

NOX2 activity is required for the generation of and detrimental effect of IL-1β. (A) gp91 ablation reduced upregulation of IL-1β gene transcription at 1 and 3 days of reperfusion (n = 8–10). (B) Western blot analysis of IL-1β at 72 h of reperfusion. Significant IL-1β overexpression was detected in the WT mice, but not in the gp91 KO mice. Con, contralateral; Ipsi, ipsilateral. (C) Summarized data from (B) (*p < 0.05 vs. WT mice). Summarized data are presented as a ratio of *p < 0.05 vs. WT mice, and as a ratio of ipsilateral side/contralateral side (n = 4–5). (D) NOX2 ablation abolished IL-1β-mediated brain damage (n = 9) (*p < 0.05 compared with IL-1β treatment).

Finally, we injected 2.5 ng of IL-1β or the vehicle into the mouse ventricle 30 min before and 10 min after focal ischemia. At 24 h of reperfusion, infarction volume was 72 mm3 in the IL-1β-treated WT mice, and was significantly higher than in the vehicle-injected mice (36 mm3). However, IL-1β injection failed to enhance infarction in gp91 KO mice (23 mm3 and 18 mm3 in vehicle-treated and IL-1β-injected mice, respectively) (Fig. 7D).

Discussion

Reduced brain damage and oxidative stress in NOX2 inhibition

In the present study, gp91 KO mice had 35–44% less brain infarction at 1 and 3 days of reperfusion compared with WT mice. Measuring biomarkers such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, malondialdehyde, and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine, we found in a previous study that levels of oxidative damage increased significantly after I/R. Genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition (via apocynin) of NOX2 reduced generation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, malondialdehyde, and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (Chen et al., 2009). Furthermore, we assayed the level of hydroethidine and found that fewer oxidized hydroethidine signals were detected in the gp91 KO mice at 3 h of reperfusion after focal ischemia compared with WT mice (data not shown), which indicates less O2•− generation in the gp91 KO mice after I/R. O2•− reacts with nitric oxide (NO) instantly to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO–) (NO + O2•− → ONOO–), a strong reactive nitrogen species that causes nitration and dysfunction of proteins (Beckman et al., 1990). We demonstrated the lesser protein nitration product, 3-NT, in gp91 KO mice. Therefore, NOX2 ablation significantly reduces oxidative stress and maintains protein function in vivo. Besides NOX2, it has also been reported that another NOX subunit, NOX4, is a major source of oxidative stress after stroke. NOX4 ablation reduced brain infarction by more than 60% at 24 h of reperfusion (Kleinschnitz et al., 2010). In the current study, we cannot rule out the contribution of other sources of ROS. It would be of interest to further investigate this with new approaches such as double knock-out or in vitro studies.

Minocycline, a tetracycline family antibiotic, attenuates ischemic neuronal cell death in vitro (oxygen glucose deprivation), as well as reduces post-ischemic brain infarction in vivo (Matsukawa et al., 2009). In our study, treatment with minocycline further reduced brain damage in gp91 KO mice at 3 days of reperfusion. gp91phox ablation reduces oxidative stress and alleviates inflammation-mediated secondary damage in brains after stroke (see discussion below). Minocycline has beneficial effects on inflammation and microglial activation. In addition, it also inhibits apoptotic cell death and alleviates blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption by reducing matrix metalloproteinase production after cerebral ischemia (Machado et al., 2006; Matsukawa et al., 2009; Yrjänheikki et al., 1999; Zemke and Majid, 2004). Therefore, minocycline and inhibition of NOX2 synergistically attenuate ischemic brain damage via various pathways.

NOX2 ablation inhibits microglia after I/R

Resting microglia present in the brain as ramified morphology and possess a small oval body and numerous radiating processes. When microglia are activated, they present an amoeboid cell form with a broad, flat morphology and shorter processes (Jin et al., 2010; Thomas, 1992). Activated microglia were found in the ischemic lesion as early as at 2 h of reperfusion after 2 h of MCAO (Zhang et al., 1997). Activated microglia exert brain injury by producing numerous neurotoxic molecules such as oxidants and cytokines, and by facilitating harmful leukocytes to migrate into the brain (Jin et al., 2010; Stoll et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2007). In addition to neuronal injury, microglia also potentiate damage to endothelia and contribute to post-ischemic BBB disruption in vivo (Yenari et al., 2006). Kauppinen et al. (2008) have reported that NOX2 activity is required for zinc-mediated microglial activation in vitro and in vivo. In the current study, we have shown that microglia maintain resting ramified morphology after ischemia in gp91 KO mice. Indeed, we also found less upregulation of inflammation factors and less infiltration of neutrophils in gp91 KO mice in this and a previous study (Chen et al., 2009). Taken together, NOX2 ablation alleviates the post-ischemic inflammation process and reduces progressive damage to the brain.

Injury to central nervous system tissue results in the release of chemotactic factors that stimulate microglia migration to the site of neural injury. In addition, microglia are capable of proliferating in response to ischemic lesions. Lastly, peripheral monocytes can infiltrate into the central nervous system and differentiate into active microglia (Garden and Möller, 2006). In vitro studies showed low concentrations of the NOX activators, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate or arachidonic acid, increased microglia proliferation (Mander et al., 2006). Moreover, proliferation of microglia by proinflammatory cytokine application is repressed by NOX inhibitors diphenylene iodonium or apocynin (Mander et al., 2006). In our study, the level of IBA-1 significantly increased at 1 and 3 days of reperfusion and this is consistent with the recruitment and proliferation of microglia after I/R. Furthermore, IBA-1 upregulation can be alleviated by NOX2 ablation. Thus, NOX2 plays an important role in both the activity of microglia and the quantity of microglia under cerebral ischemic conditions.

NOX2 ablation reduces inflammation factor transcription

In our previous study, NOX2 inhibition reduced post-ischemic neutrophil infiltration, as is evident by less expression of myeloperoxidase and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Chen et al., 2009). In addition to neutrophils, microglia also play a major role in the inflammatory process in the post-ischemic brain. Activated microglia release inflammation factors including IL-1β, TNFα, CCL2, and CCL3 (Allan and Rothwell, 2001). CCL2 is a small cytokine belonging to the CC-chemokine family, and it is also known as monocyte chemotactic protein-1. CCL2, which is predominantly produced by astrocytes and microglia after insult, further aggravates brain damage by recruiting more monocytes, microglia, and T cells to sites of tissue injury and increasing BBB permeability (Carr et al., 1994; Chen et al., 2003; Semple et al., 2010). CCL3, also named macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, has neutrophil chemokinetic properties and triggers H2O2 production in neutrophils (Wolpe et al., 1988). It also induces synthesis and release of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNFα, from macrophages (Fahey et al., 1992).

Both CCL2 and CCL3 are induced after cerebral ischemia in rodents (Nishi et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008). CCL2 and CCL3 promote inflammation by attracting or modulating inflammatory cells in the ischemic area (Kim et al., 1995). CCL2-deficient mice showed 30% less infarction compared with WT mice (Hughes et al., 2002). We have reported that ROS facilitate post-ischemic CCL2 and CCL3 expression (Nishi et al., 2005) Overexpression of a major anti-oxidant enzyme, copper/zinc superoxide dismutase, can reduce CCL2 and CCL3 gene transcription and protein expression after brain ischemia (Nishi et al., 2005). In this study, we further demonstrated that NOX2 ablation reduced CCL2 and CCL3 transcription. Taken together, this indicates that oxidative stress mediated by NOX2 significantly contributes to CCL2 and CCL3 transcription after focal ischemia.

Interaction between NOX2 and IL-1β

IL-1β binds to the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) on the plasma membrane and initiates formation of the functional IL-1R-associated protein complex by recruiting tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) to the IL-1R/MyD88 complex. Two signaling pathways, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), have been identified as the downstream pathways after IL-1R activation (O'Neill and Greene, 1998; Rothwell and Luheshi, 2000; Touzani et al., 1999). IL-1R activation can cause brain insults through further release of neurotoxins from glia and neurons, causing endothelial injury (Amantea et al., 2009; Touzani et al., 1999). The present study demonstrated that, in WT mice, intracerebroventricular injection of IL-1β remarkably exacerbated ischemic damage (100% greater infarction size). This is consistent with previous reports that showed the detrimental role of IL-1β in brain ischemia (Stroemer and Rothwell, 1998; Touzani et al., 2002).

In our study, genetic ablation of NOX2 abolished IL-1β-mediated brain damage. To our knowledge, this is the first report that reveals the role of NOX2 in IL-1β under ischemic conditions. After cerebral I/R, IL-1β is rapidly induced in response to cerebral ischemic damage. IL-1β further exacerbates brain damage by inducing a strong inflammatory response (Touzani et al., 1999). Therefore, Il-1β forms a feed-forward vicious cycle under cerebral ischemia. We suspect that NOX2 modulates the bio-effect of IL-1β by generating H2O2. It is well known that H2O2 can be a critical redox-signaling intermediate in addition to oxidizing macromolecules (Rhee, 2006). Cytosolic H2O2 inhibits cellular phosphates at cysteines in the catalytic site by oxidation of reactive thiols and alteration of protein structure (Rhee, 2006). NOX-generated H2O2 is also involved in the induction of the NF-κB pathway after TNFα activation (Li et al., 2009). Interestingly, NOX2-derived ROS also influence the formation of the IL-1R complex by directing the binding of TRAF6 to the IL-1R1/MyD88 complex and by forming functional IL-1R (Li et al., 2006). Clearance of H2O2 abrogated functional IL-1R formation and IL-1β-dependent NF-κB activation (Li et al., 2006). Our study showed that NOX2 ablation abolished IL-1β-caused brain damage. However, further elucidation is needed to determine whether NOX2-derived H2O2 or other downstream oxidants are involved in phosphates or function of IL-1R formation, and therefore the modulation of subsequent IL-1β signal pathways. Additional studies should increase our knowledge of the role of NOX2 in IL-1β pathways during cerebral ischemia.

In conclusion, NOX2 inhibition reduces ischemic brain damage by decreasing oxidative stress and ameliorating the inflammatory process. IL-1β plays a role in cerebral ischemic damage, and endogenous NOX2 activity is necessary for both production of IL-1β and the detrimental effect mediated by IL-1β. Our study suggests that NOX2 can be a potential therapeutic target for delayed inflammatory response after ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgements

We thank Liza Reola and Bernard Calagui for technical assistance, Cheryl Christensen for editorial assistance, and Elizabeth Hoyte for figure preparation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P50 NS014543, RO1 NS036147, and RO1 NS038653 and by the James R. Doty Endowment. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CCL2

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- CCL3

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3

- gp91 KO

gp91phox knockout

- IBA-1

ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-1R

interleukin-1 receptor

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- I/R

ischemia-reperfusion

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOX

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase

- O2•−

superoxide anion

- ONOO–

peroxynitrite

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κ-B

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- QPCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TRAF6

tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6

- WT

wild-type

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrosine

References

- Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Cytokines and acute neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:734–744. doi: 10.1038/35094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amantea D, Nappi G, Bernardi G, Bagetta G, Corasaniti MT. Post-ischemic brain damage: pathophysiology and role of inflammatory mediators. FEBS J. 2009;276:13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone FC, Feuerstein GZ. Inflammatory mediators and stroke: new opportunities for novel therapeutics. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:819–834. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard K, Krause K-H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong J-S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büki A, Okonkwo DO, Wang KKW, Povlishock JT. Cytochrome c release and caspase activation in traumatic axonal injury. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2825–2834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02825.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, Rose SS, Springer TA. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:3652–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PH. Role of oxidants in ischemic brain damage. Stroke. 1996;27:1124–1129. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.6.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PH. Reactive oxygen radicals in signaling and damage in the ischemic brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:2–14. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Song YS, Chan PH. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase is neuroprotective after ischemia-reperfusion. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1262–1272. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Hallenbeck JM, Ruetzler C, Bol D, Thomas K, Berman NEJ, et al. Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in the brain exacerbates ischemic brain injury and is associated with recruitment of inflammatory cells. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:748–755. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000071885.63724.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey TJ, III, Tracey KJ, Tekamp-Olson P, Cousens LS, Jones WG, Shires GT, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1 modulates macrophage function. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2764–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garden GA, Möller T. Microglia biology in health and disease. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PM, Allegrini PR, Rudin M, Perry VH, Mir AK, Wiessner C. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 deficiency is protective in a murine stroke model. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:308–317. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito D, Imai Y, Ohsawa K, Nakajima K, Fukuuchi Y, Kohsaka S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;57:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa H, Ohsawa K, Sasaki Y, Kohsaka S, Imai Y. Macrophage/microglia-specific protein Iba1 enhances membrane ruffling and Rac activation via phospholipase C-γ-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20026–20032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen TM, Higashi Y, Suh SW, Escartin C, Nagasawa K, Swanson RA. Zinc triggers microglial activation. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:5827–5835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1236-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Gautam SC, Chopp M, Zaloga C, Jones ML, Ward PA, et al. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J. Neuroimmunol. 1995;56:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)00138-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschnitz C, Grund H, Wingler K, Armitage ME, Jones E, Mittal M, et al. Post-stroke inhibition of induced NADPH oxidase type 4 prevents oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(9):e1000479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000479. doi:1000410.1001371/journal.pbio.1000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Harraz MM, Zhou W, Zhang LN, Ding W, Zhang Y, et al. Nox2 and Rac1 regulate H2O2-dependent recruitment of TRAF6 to endosomal interleukin-1 receptor complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:140–154. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.140-154.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Spencer NY, Oakley FD, Buettner GR, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal Nox2 facilitates redox-dependent induction of NF-κB by TNF-α. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:1249–1263. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado LS, Kozak A, Ergul A, Hess DC, Borlongan CV, Fagan SC. Delayed minocycline inhibits ischemia-activated matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 after experimental stroke. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mander PK, Jekabsone A, Brown GC. Microglia proliferation is regulated by hydrogen peroxide from NADPH oxidase. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1046–1052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa N, Yasuhara T, Hara K, Xu L, Maki M, Yu G, et al. Borlongan CV. Therapeutic targets and limits of minocycline neuroprotection in experimental ischemic stroke. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawase M, Li Y, Sato S, Chen SF, et al. Mitochondrial susceptibility to oxidative stress exacerbates cerebral infarction that follows permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mutant mice with manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:205–213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00205.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi T, Maier CM, Hayashi T, Saito A, Chan PH. Superoxide dismutase 1 overexpression reduces MCP-1 and MIP-1α expression after transient focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1312–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LAJ, Greene C. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor family: ancient signaling machinery in mammals, insects, and plants. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998;63:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JD, Williams DA, Gifford MAC, Li LL, Du X, Fisherman J, et al. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat. Genet. 1995;9:202–209. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell NJ, Luheshi GN. Interleukin 1 in the brain: biology, pathology and therapeutic target. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:618–625. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Kossmann T, Morganti-Kossmann MC. Role of chemokines in CNS health and pathology: a focus on the CCL2/CCR2 and CXCL8/CXCR2 networks. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:459–473. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll G, Jander S, Schroeter M. Inflammation and glial responses in ischemic brain lesions. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;56:149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroemer RP, Rothwell NJ. Exacerbation of ischemic brain damage by localized striatal injection of interleukin-1β in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:833–839. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WE. Brain macrophages: evaluation of microglia and their functions. Brain Res. Rev. 1992;17:61–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(92)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touzani O, Boutin H, Chuquet J, Rothwell N. Potential mechanisms of interleukin-1 involvement in cerebral ischaemia. J. Neuroimmunol. 1999;100:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touzani O, Boutin H, LeFeuvre R, Parker L, Miller A, Luheshi G, et al. Interleukin-1 influences ischemic brain damage in the mouse independently of the interleukin-1 type I receptor. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:38–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00038.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walder CE, Green SP, Darbonne WC, Mathias J, Rae J, Dinauer MC, et al. Ischemic stroke injury is reduced in mice lacking a functional NADPH oxidase. Stroke. 1997;28:2252–2258. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HK, Park UJ, Kim SY, Lee JH, Kim SU, Gwag BJ, et al. Free radical production in CA1 neurons induces MIP-1α expression, microglia recruitment, and delayed neuronal death after transient forebrain ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:1721–1727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4973-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Tang XN, Yenari MA. The inflammatory response in stroke. J. Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe SD, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse DG, Nguyen HT, et al. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J. Exp. Med. 1988;167:570–581. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yenari MA, Xu L, Tang XN, Qiao Y, Giffard RG. Microglia potentiate damage to blood-brain barrier constituents. Improvement by minocycline in vivo and in vitro. Stroke. 2006;37:1087–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206281.77178.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yrjänheikki J, Tikka T, Keinänen R, Goldsteins G, Chan PH, Koistinaho J. A tetracycline derivative, minocycline, reduces inflammation and protects against focal cerebral ischemia with a wide therapeutic window. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:13496–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemke D, Majid A. The potential of minocycline for neuroprotection in human neurologic disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:293–298. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000150867.98887.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chopp M, Powers C. Temporal profile of microglial response following transient (2 h) middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain Res. 1997;744:189–198. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)01085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]