Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the association of 3-dimensional changes in the position of the condyles, rami, and chin at splint removal and 1 year after mandibular advancement surgery.

Patients and Methods

This prospective observational study used preoperative and postoperative scans of 27 subjects presenting with a skeletal Class II jaw relationship with a normal or deep overbite. An automatic technique of cranial base superimposition was used to assess the positional and/or remodeling changes in the anatomic regions of interest. The displacements were visually displayed and quantified using 3-dimensional color maps. The positive and negative values of surface distances in the color maps indicated the direction of the displacements. Pearson correlation coefficients and a linear model for correlated data were used to evaluate the association between the regional displacements.

Results

The postoperative adaptations in the chin position between splint removal and 1 year after surgery were significantly negatively correlated with changes in the borders of the posterior ramus (left, r = −0.73, P ≤ .0001; and right, r = −0.68, P = .00) and the condyles (left, r = −0.53, P = .01; and right, r = −0.46, P = .02), indicating that these structures tended to be displaced in the same direction. Even though the mean condylar displacement with surgery was less than 1 mm, individual displacements greater than 2 mm with surgery were observed for 24% of the condyles. The condylar displacements were maintained at 1 year after surgery for 17% of the condyles.

Conclusions

The surface distance displacements indicated that the postoperative adaptations at different anatomic regions were significantly related.

Although mandibular advancement surgery is considered a highly stable procedure,1,2 postoperative changes, such as rotation, transverse condylar displacements during surgery,3–5 and subsequent long-term condylar resorption have been suggested as factors leading to sagittal relapse and anterior bite opening.6–8 Therefore, the postoperative instability of bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy due to displacement of the condyle from its seated position in the glenoid fossa in the 3 planes of space remains an area of concern.9,10

Recent assessments of 3-dimensional (3D) skeletal changes 1 year after mandibular advancement surgery have shown individual variability in postoperative adaptations, with a greater than 2-mm relapse of the chin position in 28% of the patients, with additional advancement of the chin position in 20% of the patients.11 The use of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and 3D superimposition tools now allow assessment of the relationships of the surface adaptations among the dental, skeletal, and soft tissue components that was not possible with 2-dimensional landmark linear or angular measures. These methods have the potential to highlight the associations between the structural changes and the stability of surgical correction.12,13

The present study investigated whether surface distance displacements with surgery are associated with postoperative instability. Specifically, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the association of 3D changes in the position of the condyles, rami, and chin at splint removal and 1 year after mandibular advancement surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

PEARSON CORRELATION COEFFICIENTS FOR SURGICAL DISPLACEMENTS AND POSTOPERATIVE ADAPTATIONS BETWEEN ALL THE ANATOMIC REGIONS OF INTEREST

| Preoperative to Splint Removal Versus Splint Removal to 1-Year Postoperatively | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1–T2 | T2–T3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chin | LPB | RPB | LC | RC | RSR | RIR | LSR | LIR | Chin | LPB | RPB | LC | RC | RSR | RIR | LSR | LIR | |

| T1–T2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chin | −0.26 | −0.18 | −0.34 | −0.28 | 0.46* | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.14 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.10 | |

| LPB | 0.21 | 0.69* | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.42* | 0.22 | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.12 | −0.14 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | |

| RPB | 0.40 | <0.0001* | −0.14 | 0.18 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.17 | |

| LC | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.66* | −0.33 | −0.14 | −0.21 | −0.31 | 0.24 | −0.29 | −0.13 | −0.51* | −0.17 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.02 | −0.14 | |

| RC | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.00* | −0.22 | 0.04 | −0.30 | −0.21 | 0.16 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.28 | −0.33 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.17 | −0.01 | |

| RSR | 0.02* | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.58* | 0.46* | 0.09 | −0.20 | 0.20 | −0.04 | 0.20 | 0.10 | −0.21 | −0.18 | 0.14 | −0.02 | |

| RIR | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.76 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.00* | 0.21 | −0.18 | −0.30 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.27 | −0.15 | −0.19 | −0.20 | −0.34 | |

| LSR | 0.71 | 0.03* | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.01* | 0.30 | 0.66* | −0.39 | 0.39* | 0.23 | 0.39* | 0.15 | −0.17 | −0.17 | −0.06 | −0.06 | |

| LIR | 0.67 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 0.00* | −0.11 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.30 | −0.08 | −0.02 | −0.17 | 0.08 | 0.13 | |

| T2–T3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chin | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.60 | −0.73* | −0.68* | −0.53* | −0.46* | 0.43* | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.25 | |

| LPB | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.04* | 0.28 | <0.0001* | 0.74* | 0.54* | 0.40* | −0.26 | −0.24 | −0.24 | −0.41* | |

| RPB | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.91 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.69 | 0.00* | <0.0001* | 0.43* | 0.52* | −0.33 | −0.19 | −0.25 | −0.32 | |

| LC | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.01* | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.05* | 0.13 | 0.01* | 0.00* | 0.02* | 0.45* | −0.32 | −0.40* | −0.01 | 0.14 | |

| RC | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 0.44 | 0.71 | 0.02* | 0.04* | 0.01* | 0.02* | −0.08 | 0.21 | −0.28 | −0.32 | |

| RSR | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.90 | 0.03* | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.70 | 0.67* | −0.20 | 0.06 | |

| RIR | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.04* | 0.29 | 0.00* | −0.34 | −0.18 | |

| LSR | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.94 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.95 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.74* | |

| LIR | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.03* | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.36 | <0.0001* | |

Abbreviations: T1, preoperative assessment; T2, assessment at splint removal 6 weeks after surgery; T3, 1 year after surgery; LPB, left posterior border; RPB, right posterior border; LC, left condyle; RC, right condyle; RSR, right superior ramus; RIR, right inferior ramus; LSR, left superior ramus; LIR, left inferior ramus.

Left superior quadrant, preoperatively to splint removal (T1–T2); right inferior quadrant, splint removal to 1 year after surgery (T2–T3); right superior and left inferior quadrants, preoperatively to splint removal versus splint removal to 1 year after surgery (T1 – T2 × T2 – T3). Right superior shows r values and left inferior, P values.

Statistically significant.

Patients and Methods

A total of 27 patients (9 men and 18 women, mean age 30.04 ± 13.08 years), who had undergone surgery at the University of North Carolina Memorial Hospital with a surgeon and resident assistant from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, were recruited for the present prospective observational study. All patients had skeletal Class II discrepancies, with a normal or short face height. The patients underwent orthodontic treatment and mandibular advancement surgery with bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy, and 9 also underwent genioplasty as an adjunctive procedure. Patients with excessive face height, congenital problems (including cleft lip/palate), or skeletal disharmonies resulting from trauma or degenerative conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis were excluded. All patients provided informed consent, and the biomedical institutional review board approved the project.

CBCT scans were taken before surgery (time 1 [T1]), at splint removal 6 weeks after surgery (T2), and 1 year after surgery (T3) using the NewTom 3G scanner (Aperio Services, Sarasota, FL). The imaging protocol involved a 36-second head CBCT scan with a field of view of 230 × 230 mm, acquired in centric occlusion under the supervision of a trained radiology technician. Two of the patients had at least 1 scan done with the NewTom 9000 (Aperio Services), which has a smaller field of view that did not include the chin; thus, the changes in chin position could be observed for only 25 patients.

Image segmentation of the anatomic structures of interest and the 3D graphic rendering were constructed using the ITK-SNAP open-source software14,15 and CBCT images with a voxel dimension of 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm. A fully automated voxel-wise rigid registration method was used through the IMAGINE free software (developed by the National Institutes of Health and modified at the University of North Carolina),12,16 which compares 2 images using the intensity of the gray scale for each voxel of the cranial base, because this structure was not altered by surgery. The preoperative cranial base was used as a reference for the superimposition of the images at splint removal and 1 year after surgery (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

A, After registration procedure with IMAGINE software, superimposition between 3D model (color) and gray scale preoperative image can be observed with ITK-SNAP software, showing matching cranial bases and displaced mandibular structures (mandibular advancement and genioplasty). Aa, axial; Ab, sagittal; Ad, coronal; Ac, note 3D toolbox has tool for painting specific anatomic regions of interest. B, Anatomic regions of interest: 1, right condyle; 2, left condyle; 3, right posterior ramus; 4, left posterior ramus; 5, right superior ramus; 6, left superior ramus; 7, right inferior ramus; 8, left inferior ramus; and 9, chin; Ba, right view; Bb, left view.

After the registration step, all the reoriented virtual models, originally saved in a “.gipl” format, were converted to an SGL open inventor format (“.iv”) using the software Vol2Surf, allowing the quantitative evaluation of the greatest displacements by the CMF application software (Maurice Müller Institute, Bern, Switzerland).17

After registration, 3 surface model superimpositions were assessed: T1 to T2 (preoperatively to splint removal superimposition to assess the immediate surgical outcome), T1 to T3 (preoperatively to 1 year postoperatively to assess the 1-year postoperative outcomes), and T2 to T3 (splint removal to 1 year after surgery to determine the postoperative adaptations). The CMF tool calculates thousands of color-coded surface distances in millimeters between two 3D models using surface triangles at 2 different points, such that the difference between the 2 surfaces at any location can be quantified. In addition to observation of the color maps showing the total pattern of change, the isolines (contour line) tool was used to quantitatively measure the greatest displacement (in millimeters) for 9 specific anatomic regions of interest: condyles (right and left), posterior rami (right and left), superior rami (right and left), inferior rami (right and left), and chin.

The color maps15 indicated the inward (blue) and outward (red) displacement between the overlaid structures. An absence of change was indicated by green. For example, for mandibular advancement surgery, the forward chin displacement would be shown in red and for mandibular setback surgery, the chin surfaces would be shown in blue. Semitransparent overlays were also used for visualization of the location and direction of the skeletal displacements, with 1 of the models in an opaque view superimposed onto another partially transparent view (Figs 2, 3). This method for showing quantitative changes at multiple locations has been validated and used since 2005.12

FIGURE 2.

Visualization of right condyle displaced posteriorly, superiorly, and medially between preoperative and postoperative images. A, Color-coded maps indicate outward displacements in red and inward displacements in blue; B, Semitransparencies with preoperative image in solid white and postoperative in transparent red. A, anterior P, posterior.

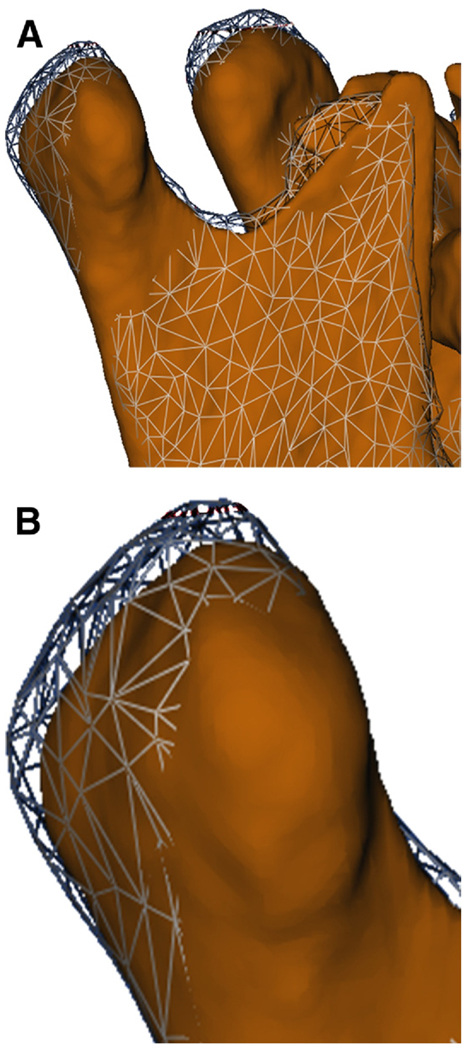

FIGURE 3.

A, Different method to visualize displacements, with mesh-transparencies showing condyle displacement of 3.2 mm after surgery. B, Close-up view of displaced condyle.

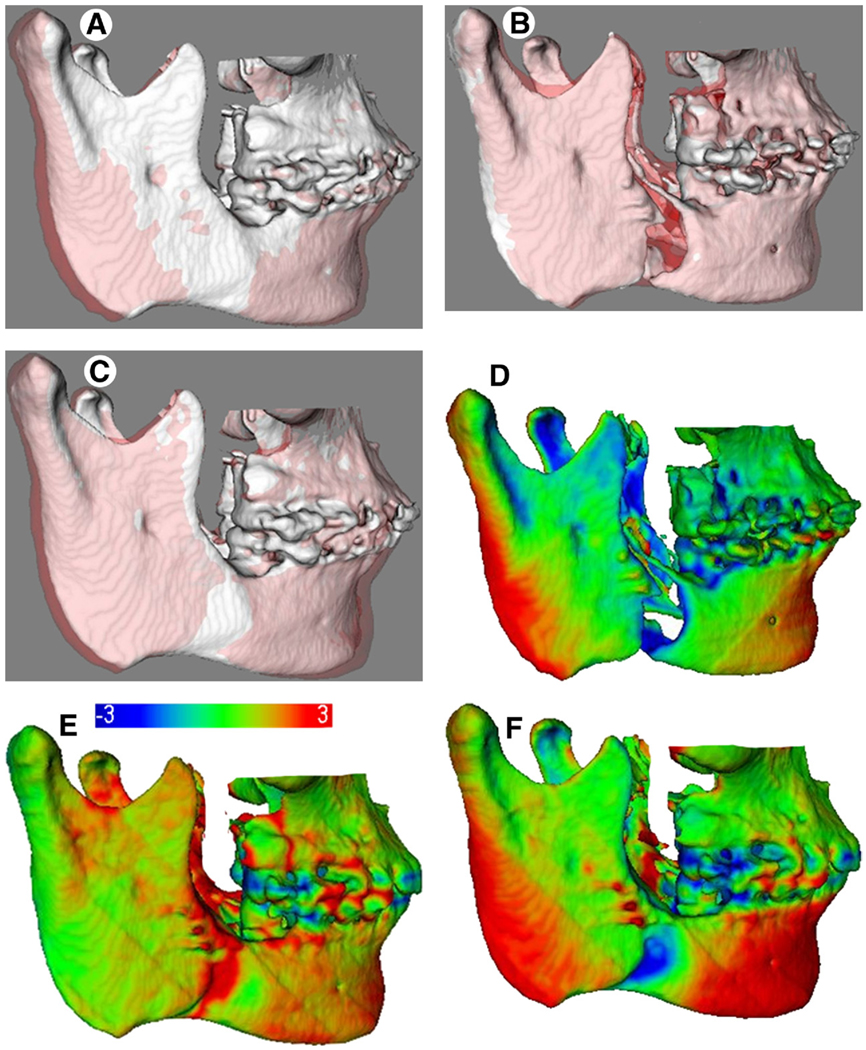

Positive values indicated an anteroinferior displacement of the chin and negative values, a posterosuperior displacement. For the condyles, positive values represented a posterosuperior displacement and negative values an anteroinferior displacement. For the rami posterior borders, positive values represented posterior displacements and negative values indicated anterior displacements (Fig 4). The lateral portion of the mandibular rami was divided into 2 parts (superior and inferior), to identify the complex torque or medial/lateral movement of this region. Thus, positive values represented a lateral displacement of the rami, and negative values a medial displacement. When the superior and inferior portions of the ramus showed displacements in opposite directions, this indicated a torque movement of this anatomic region.

FIGURE 4.

Color map of 3D surface model at 1 year after surgery displaying surface distances of changes between splint removal and 1 year follow-up examination. Visual illustration of how displacements in same direction (posterior) shown using different colors at different anatomic regions: chin shown in blue and posterior border of ramus in red. Note, blue indicates inward displacements relative to bony surfaces at splint removal and red indicates outward displacements.

The largest surface displacements of the condyles, rami, and chin between T1 and T2 (immediate surgical outcome) and T2 and T3 (postoperative adaptations) were computed. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the simple bivariate linear association of the surface distance displacements among the anatomic regions (eg, whether changes at the condyles and/or ramus were associated with changes at the chin). Because multiple linear regression analysis with highly correlated predictors can be problematic, the T2 to T3 surface displacements of the chin were modeled using an approach18 that accounts for the correlations between the explanatory measurements (the right and left condyle displacements and the right and left posterior border displacements). An intercept-only linear model for correlated data was used to obtain the estimated multivariate normal distribution for all 5 displacements. The assumption of the multivariate normality of the displacement measures was reasonable, given the distributions of each displacement. Using properties of the conditional multivariate normal distribution,18 the estimated mean of chin displacement was calculated as a function of the 4 explanatory variables, and the variance of chin displacement was then calculated. The level of significance was set at P = .05.

Results

The analysis of the average surgical and postoperative displacements for each anatomic region and the descriptive statistics for this sample have been described in detail by Carvalho et al.11 The mean chin advancement at splint removal (chin T1 to T2 changes 6.8 ± 3.2 mm) was maintained at 1 year after surgery (mean chin T1 to T3 changes 6.4 ± 3.4 mm). For all other anatomic regions evaluated, only the inferior rami (left 3.0 ± 2.7 mm and right 2.3 ± 2.4 mm) had a mean displacement of 2 mm or more with surgery. The mean condylar displacement with surgery was 0.98 ± 1.46 mm on the left and 0.81 ± 1.40 mm on the right, and these small mean displacements were maintained at the 1-year follow-up visit (condylar T1 to T3 changes, left 1.15 ± 1.54 mm and right 0.85 ± 1.59 mm).

BIVARIATE CORRELATIONS BETWEEN ANATOMIC REGIONAL SURGICAL CHANGES (T1 TO T2 SUPERIMPOSITION)

Between the baseline (before surgery) measurement and splint removal, anterior displacement of the chin correlated with the lateral movement of the superior portion of the right ramus (r = 0.46, P = .02). The surface displacements of the right and left sides of the anatomic regions were positively correlated. The posterior movement of the ramus posterior border (r = 0.69, P < .0001), posterosuperior displacement of the condyles (r = 0.66, P = .0002), and lateral displacement of the superior portions of the rami (r = 0.46, P = .0148). On both the right and the left, the superior and inferior portion of the ramus correlated, showing a lateral movement tendency (right, r = 0.58, P = .0016; left, r = 0.66, P = .0002; Fig 5).

FIGURE 5.

Semitransparent overlay of 3D surface models with preoperative image (white) and splint removal (red). A, Visualization showing 6.8-mm mandibular advancement measured at chin. B, Posterior view of lateral displacements of rami (proximal surgical segments). Sagittal osteotomy probably acted as a wedge and condyles as a fulcrum, causing displacement of inferior part of rami.

BIVARIATE CORRELATIONS BETWEEN ANATOMIC REGIONAL POSTOPERATIVE CHANGES (T2 TO T3 SUPERIMPOSITION)

Postoperatively, the surface displacements of the right and left sides of the anatomic regions were positively correlated for some regions: anterior movement of the ramus posterior border (r = 0.74, P ≤ .0001), and anteroinferior displacement of the condyles (r = 0.45, P = .02). On both the right and the left, the superior and inferior portions of the ramus were correlated, showing a medial movement (right, r = 0.67, P = .00; left, r = 0.74, P ≤ .0001). Postoperative adaptations in the chin position were significantly negatively correlated with surface displacements in the posterior ramus borders (left, r = −0.73, P ≤ .0001; and right, r = −0.68, P = .00) and the condyles (left, r = −0.53, P = .01; and right, r = −0.46, P = .02), indicating a displacement in the same direction for these structures (Fig 3).

ADAPTATION OF CHIN

Using the properties of the conditional multivariate normal distribution,18 the estimated mean of the chin displacement could be expressed as E(chin displacement) = 0.1925 − 0.1606RC − 0.6055RPB − 0.5247LPB − 0.2992LC, where RC is the right condyle; LC, the left condyle; RPB, the right ramus posterior border; and LPB, the left ramus posterior border. The standard error of the estimated mean chin displacement was 1.57 mm. The inclusion of the surface displacement values for the right and left condyles and right and left posterior ramus borders in the model decreased the variability in chin displacement by 61%. The variability of the observed chin displacements was 6.27 mm, and the variability of the estimated chin displacement, given the data from the 4 explanatory measures of surface displacement, was 2.47 [(6.27 − 2.47)/6.27 − 61%] (Fig 6).

FIGURE 6.

Graphic display of observed and predicted mean chin displacement given explanatory measures of right and left condyles and posterior ramus borders using multivariate normal modeling approach. Postoperative displacements of condyles and posterior borders explained 67% of variability in adaptation of the chin (observed chin displacement).

Discussion

From the 2-dimensional cephalometric data of an extensive database, the hierarchy of stability studies1,2,19 indicated that mandibular advancement surgery in Class II patients with a normal or short face is 1 of the most stable surgery procedures. The preliminary 3D assessments by Carvalho et al,11 however, found marked individual variability in the postoperative adaptations after mandibular advancement. The variability in postoperative adaptations requires additional investigation using 3D superimposition methods.

Although surgeons strive to maintain the condyles seated in the articular fossa during surgery, the rami and condyles are often displaced during mandibular advancement surgery. The study findings of 2-mm or greater lateral displacements with surgery of 35 of the 54 right and left rami probably resulted from the osteotomy cuts in the inferior portion of the rami. The mean 5.28-mm sum of the displacements for the right and left sides at the inferior portion of the rami in the present study has corroborated the findings of Becktor et al,8 although different measurement methods were used. However, in our study, neither the amount of chin advancement nor the lateral displacement of the inferior portion of the rami with surgery (T1 to T2) correlated significantly with the postoperative (T2 to T3) adaptations of any other anatomic regions.

Although the 2-mm or greater mean changes with surgery were observed at the condyles and other regions of the rami, individual variability revealed a range of displacements greater than the clinically acceptable limits. Patients with larger posterior condylar displacements between T1 and T2 presented with marked postoperative condylar adaptations. These displacements are difficult to predict during surgery, and this is an area of concern, especially for patients at a high risk of temporomandibular disorders,20,21 even though temporomandibular disorder symptoms were not observed in our sample.

The interpretation of the 3D direction of the surface changes in the present study was aided by the visual assessment of the color maps to properly describe the directional changes. The significant correlation between the postoperative adaptations at the chin and at the condyles and posterior border of the rami indicated that changes occurred in the same posterosuperior direction for these regions (Fig 4). Adaptations of the condyles and posterior border of the ramus accounted for 61% of the adaptations at the chin. Our results showed that 17% of the condyles still had greater than 2-mm displacements at 1 year after surgery, indicating the continuation of postoperative adaptations in the long-term assessments.

The marked individual variability of the displacements of the surgical segments (Fig 7) suggested that mandibular advancements with truly anterior displacement of the corpus without a vertical component (as exemplified in Fig 8) were more stable postoperatively. However, our findings showed that postoperative adaptations frequently resulted in additional anterior movement of the chin in patients who had undergone clockwise rotation of the mandibular corpus, with greater vertical than horizontal changes with surgery, such as in the case illustrated in Figs 9 and 10. Our study sample was not large enough to statistically assess the vertical differences in subgroups, and future studies with larger samples and long-term follow-up are needed.

FIGURE 7.

Semitransparencies between preoperative (solid white) and at splint removal (transparent red) 3D models for 2 patients in present study. Note, variability of surgical displacements to advance mandible. A, In some cases, mandibular advancement was accompanied by vertical increase, and B, other patients had more anterior advancement. Also note, small, but varying, condylar displacements.

FIGURE 8.

Example of patient with anterior displacement of corpus with mandibular advancement, complemented by adjunctive chin advancement with genioplasty. A–C, Superimposition of semitransparencies; D–F, surface distance color maps between models in Figs A, B, and C, respectively. A, Preoperative (white) to splint removal (semitransparent red); B, splint removal (white) to 1 year postoperatively (semitransparent red); C, preoperative (white) to 1 year postoperatively (semitransparent red). Comparison between Figs A and C (preoperative in white) showed that small condylar and rami displacements occurred with surgery, but surgical results were maintained at 1 year of follow-up. Color maps in Fig E also revealed stability of results in postoperative period.

FIGURE 9.

Example of patient who presented with more vertical than horizontal changes shown in superimpositions with color maps (Left) and semitransparencies (Right). Small overjet but deep overbite was present, and improvement of the lower facial height was planned. A–C, Superimposition of semitransparencies; D–F, surface distance color maps between models in Figs A, B, C, respectively. A, Preoperative (white) to splint removal (semitransparent red) showing large posterior displacement at rami and condyles and vertical displacement at chin with surgery. B, Splint removal (white) to 1 year postoperatively (semitransparent red) showing mandibular anterior movement in postoperative adaptation period. C, Preoperative (white) to 1 year postoperatively (semitransparent red). Note, slight additional anterior movement in Fig B resulted in more marked and improved chin anterior and vertical displacements in Fig C, with some of posterior displacement at condyles and rami maintained 1 year after surgery.

FIGURE 10.

A–C, Preoperative and D–F, 1 year postoperative photographs of patient described in Figure 9. Note, effect of lateral displacement of rami in frontal photograph, A, D.

Superimposition of 3D virtual surface models clearly showed the associations of postoperative adaptations of different anatomic regions after mandibular advancement surgery. The postoperative adaptation of the condyles and rami were associated with changes in the chin position at 1 year postoperatively, and these adaptations could lead to maintenance, additional improvement, or relapse of the surgical results.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dorothy L. Long, doctoral student in the University of North Carolina Department of Biostatistcs, for assistance with multivariate modeling.

This study was supported by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (grants DE017727, DE018962, DE005215, and CAPES 3827-05-4).

References

- 1.Bailey LJ, Cevidanes LH, Proffit WR. Stability and predictability of orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2004;126:273. doi: 10.1016/S0889540604005207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proffit WR, Turvey TA, Phillips C. Orthognathic surgery: A hierarchy of stability. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1996;11:191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Efstratiadis S, Baumrind S, Shofer F, et al. Evaluation of Class II treatment by cephalometric regional superimpositions versus conventional measurements. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2005;128:607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa F, Robiony M, Toro C, et al. Condylar positioning devices for orthognathic surgery: A literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:179. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alder ME, Deahl ST, Matteson SR, et al. Short-term changes of condylar position after sagittal split osteotomy for mandibular advancement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:159. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Clercq CA, Neyt LF, Mommaerts MY, et al. Condylar resorption in orthognathic surgery: A retrospective study. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1994;9:233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris MD, Van Sickels JE, Alder M. Factors influencing condylar position after the bilateral sagittal split osteotomy fixed with bicortical screws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:650. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becktor JP, Rebellato J, Becktor KB, et al. Transverse displacement of the proximal segment after bilateral sagittal osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:395. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.31227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becktor JP, Rebellato J, Becktor KB, et al. Transverse displacement of the proximal segment after bilateral sagittal osteotomy: A comparison of lag screw fixation versus miniplates with monocortical screw technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:104. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.06.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schendel SA, Epker BN. Results after mandibular advancement surgery: An analysis of 87 cases. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho FAR, Cevidanes LHS, Motta A, et al. 3D assessment of mandibular advancement 1 year after surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 137 suppl 4 doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.01.017. S53.e1–e12, 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cevidanes LH, Bailey LJ, Tucker GR, Jr, et al. Superimpositon of 3D cone-beam CT models of orthognathic surgery patients. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2005;34:369. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/17102411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cevidanes LH, Franco AA, Gerig G, et al. Assessment of mandibular growth and response to orthopedic treatment with 3-dimensional magnetic resonance images. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2005;128:16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerig G, Jomier M, Chakos M. Valmet: A new validation tool for assessing and improving 3D object segmentation. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2001;2208:516. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, et al. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: Application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18:712. doi: 10.1109/42.796284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapuis J, Schramm A, Pappas I, et al. A new system for computer-aided preoperative planning and intraoperative navigation during corrective jaw surgery. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2007;11:274. doi: 10.1109/titb.2006.884372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao CR. Linear Statistical Inference and Its Application. ed 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proffit WR, Turvey TA, Phillips C. The hierarchy of stability and predictability in orthognathic surgery with rigid fixation: An update and extension. Head Face Med. 2007;30:3–21. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang SJ, Haers PE, Zimmermann A, et al. Surgical risk factors for condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:542. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.105239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuinzing DB. Discussion of Harris et al. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:654. [Google Scholar]