Abstract

Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is one of the most common anxiety conditions with impairment in social life. Cannabidiol (CBD), one major non-psychotomimetic compound of the cannabis sativa plant, has shown anxiolytic effects both in humans and in animals. This preliminary study aimed to compare the effects of a simulation public speaking test (SPST) on healthy control (HC) patients and treatment-naïve SAD patients who received a single dose of CBD or placebo. A total of 24 never-treated patients with SAD were allocated to receive either CBD (600 mg; n=12) or placebo (placebo; n=12) in a double-blind randomized design 1 h and a half before the test. The same number of HC (n=12) performed the SPST without receiving any medication. Each volunteer participated in only one experimental session in a double-blind procedure. Subjective ratings on the Visual Analogue Mood Scale (VAMS) and Negative Self-Statement scale (SSPS-N) and physiological measures (blood pressure, heart rate, and skin conductance) were measured at six different time points during the SPST. The results were submitted to a repeated-measures analysis of variance. Pretreatment with CBD significantly reduced anxiety, cognitive impairment and discomfort in their speech performance, and significantly decreased alert in their anticipatory speech. The placebo group presented higher anxiety, cognitive impairment, discomfort, and alert levels when compared with the control group as assessed with the VAMS. The SSPS-N scores evidenced significant increases during the testing of placebo group that was almost abolished in the CBD group. No significant differences were observed between CBD and HC in SSPS-N scores or in the cognitive impairment, discomfort, and alert factors of VAMS. The increase in anxiety induced by the SPST on subjects with SAD was reduced with the use of CBD, resulting in a similar response as the HC.

Keywords: cannabidiol, CBD, anxiety, simulation of public speaking test, SPST, social anxiety disorder

INTRODUCTION

Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is one of the most common anxiety conditions and is associated with impairment in social adjustment to the usual aspects of daily life, increased disability, dysfunction, and a loss of productivity (Kessler, 2007; Filho et al, 2010). SAD tends to follow a long-term and unremitting course and is rarely resolved without treatment (Crippa et al, 2007; Chagas et al, 2010).

The pharmacological management of SAD remains problematic, despite several guidelines or consensus statements issued over the past few years (Canadian Psychiatric Association, 2006; Montgomery et al, 2004). As this anxiety disorder is often poorly controlled by the currently available drugs (only about 30% of the subjects achieve true recovery or remission without residual symptomatology (Blanco et al, 2002)), there is a clear need to search for novel therapeutic agents.

Subjects with SAD seem to be more likely to use cannabis sativa (cannabis) than those without other anxiety disorders to ‘self-medicate' anxiety reactions (Buckner et al, 2008). However, the relationship of cannabis with anxiety is paradoxical. Cannabis users reported the reduction of anxiety as one of the motivations for its use; on the other hand, episodes of intense anxiety or panic are among the most common undesirable effects of the drug (Crippa et al, 2009). These apparently conflicting statements may partly reflect the fact that low doses of the best-known constituent of the plant, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), engender anxiolytic-like effects, whereas higher doses produce anxiogenic reactions (Crippa et al, 2009).

Moreover, other components of the plant can influence its pharmacological activity; in particular, cannabidiol (CBD), one major non-psychotomimetic compound of the plant, has psychological effects substantially different from those of 9-THC (Zuardi, 2008). Oral administration of CBD to healthy volunteers has been shown to attenuate the anxiogenic effect of Δ9-THC and does not seem to involve any pharmacokinetic interactions (Zuardi et al, 1982). In animal studies, CBD has similar effects to anxiolytic drugs in different paradigms including conditioned emotional response, the Vogel conflict test, and the elevated plus-maze test (Zuardi, 2008). In human studies, the anxiolytic effects of CBD have been elicited in subjects submitted to the Simulation Public Speaking Test (SPST) (Zuardi et al, 1993). Using functional neuroimaging in healthy volunteers, we have observed that CBD has anxiolytic properties and that these effects are associated with an action on the limbic and paralimbic brain areas (Fusar-Poli et al, 2009a; Crippa et al, 2004).

Recently, we investigated the central effects of CBD on regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF), using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in patients with SAD. Relative to placebo, CBD was associated with significant decreases in subjective anxiety induced by the SPECT procedure and modulated the same brain areas as the healthy volunteers (Crippa et al, 2010, 2011).

The data reviewed above led to the hypothesis that CBD may be an effective compound in the treatment of SAD symptoms. As a first step to investigate this hypothesis, we used the SPST, an experimental model for the induction of anxiety. SPST has apparent and predictive validity for SAD because the fear of speaking in public is a cardinal manifestation of SAD, and there is pharmacological evidence that the response pattern to some substances in the SPST is similar to the clinical response presented by patients with SAD (Graeff et al, 2003; Brunello et al, 2000). In this preliminary study, we aimed to measure the subjective and physiological effects of SPST on healthy control (HC) and on treatment-naïve SAD patients, who received a single dose of CBD or placebo, in a double-blind design. We have decided to use a single dose of CBD because of ethical and economical constraints, as a first step in the investigation of a possible anxiolytic action of this cannabinoid in patients with pathological anxiety. For instance, it is important to confirm whether CBD has the advantage of a rapid onset of action, making it particularly suitable for individuals who have episodic performance-related social phobia and who are able to predict the need for treatment well in advance. Considering previous results from a single dose of CBD, it is expected that this cannabinoid will reduce the level of fear provoked by the SPST.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 24 subjects with generalized SAD and 12 HC subjects were selected by the screening procedure described below (see section). The SAD patients were randomly assigned to the two groups with 12 subjects each to receive CBD (600 mg—SAD-CBD) or placebo (SAD-PLAC), in a double-blind study design. To ensure the adequacy of the matching procedure, the first participant had his treatment blindly chosen between the two treatment options available; the next participant (whose characteristics were matched to the first one's) had his treatment drawn from the remaining option. An equal number of healthy controls (n=12) performed the test without receiving any medication (HC). The groups were matched according to gender, age, years of education, and socioeconomic status. Moreover, the two SAD groups were balanced according to the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN (Connor et al, 2000)). All participants were treatment-naïve (either with pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy) and did not present any other concomitant psychiatric disorder. No subject had a history of head trauma, neurological illness, ECT, substance abuse, or major medical illnesses, based on a semi-standardized medical questionnaire and physical examination. They were all non-smokers (of tobacco) and had not taken any medications for at least 3 months before the study. None of the subject had used marijuana more than five times in their lives (no use in the last year) and none had ever used any other illegal drug. All subjects gave written informed consent after being fully informed about the research procedure, following approval by the local ethical committee (HCRP No. 12407/2009).

Screening Procedure and Clinical Assessment

As an initial step, 2319 undergraduate students were screened by a self-assessment diagnostic instrument, the short version of the Social Phobia Inventory named MINI-SPIN (Osório Fde et al, 2010; Connor et al, 2001). This led to the identification of subjects with probable SAD, who scored a minimum of six points in the three items that compose the MINI-SPIN. Using this cut-off score, the MINI-SPIN has been previously shown to provide high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of SAD (de Lima Osório et al, 2007; Connor et al, 2001). A total of 237 subjects with a positive MINI-SPIN and an equal number of subjects with zero points in the three items that compose this instrument were contacted by telephone in order to respond to the general revision and the social anxiety module of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, clinical version (SCID-CV (First et al, 1997), translated into Portuguese (Del-Ben et al, 2001)). The volunteers who fulfilled SAD criteria and scored ‘very much' or ‘extremely' in the 11th item of SPIN (avoids speeches) and those who fulfilled the HC criteria were randomly invited to attend an interview for diagnosis confirmation through the full SCID-CV, applied by two examiners familiar with the instrument (the Kappa coefficient between the two interviewers was 0.84 (Crippa et al, 2008a)).

CBD Preparation

CBD (600 mg) in powder, ∼99.9% pure (kindly supplied by STI-Pharm, Brentwood, UK and THC-Pharm, Frankfurt, Germany), was dissolved in corn oil (Crippa et al, 2004; Zuardi et al, 1993). The same amount of corn oil was used as placebo. The drug and placebo were packed inside identical gelatin capsules. We have chosen the dose of 600 mg based on the fact that acute anxiolytic effects of CBD have been observed in healthy controls with doses ranging from 300 (Zuardi et al, 1993) to 600 mg (Fusar-Poli et al, 2009a, 2009b). Although we have recently observed that 400 mg of CBD significantly decreased subjective anxiety induced by the SPECT procedure in SAD patients, the SPST has face validity for SAD and the fear of speaking in public is considered to be the most stressful situation in this condition, in contrast with the neuroimaging procedure. Therefore, we have decided to use the highest dose of CBD previously found to have anxiolytic effects. The time of assessment after the procedure was chosen based on previous studies that showed that the plasma peak of an oral dose of CBD usually occurs 1–2 h after ingestion (Agurell et al, 1981; Crippa et al, 2004, 2010, 2011; Borgwardt et al, 2008; Fusar-Poli et al, 2009a, 2009b)

Psychological Measurements

The state-anxiety level and other subjective states were evaluated during the test through the Visual Analogue Mood Scale—VAMS (Norris, 1971), translated into Portuguese (Zuardi and Karniol, 1981). In this scale, the subject is told to mark a point that identifies his/her present subjective state on a 100-mm straight line placed between two words that describe opposite mood states. VAMS contains 16 items that Norris grouped into four factors. A factorial analysis performed with the Portuguese version of the VAMS also yielded four factors with similar item composition (Zuardi et al, 1993). The original name of the anxiety factor was preserved, but the names of the remaining factors have been changed to fit the meaning of the items with the highest loads in that particular factor. Thus, the present factors are: (1) anxiety, comprising the items calm–excited, relaxed–tense, and tranquil–troubled; (2) sedation (former mental sedation), including the items alert–drowsy, and attentive–dreamy; (3) cognitive impairment (former physical sedation), including quick-witted–mentally slow, proficient–incompetent, energetic–lethargic, clear-headed–muzzy, gregarious–withdrawn, well-coordinated–clumsy, and strong–feeble; and (4) discomfort (former other feelings and attitudes), made of the items interested–bored, happy–sad, contented–discontented, and amicable–antagonistic (Parente et al, 2005).

The Self-Statements during Public Speaking Scale (Hoffmann and Di Bartolo, 2000) (SSPS), translated into Portuguese (de Lima Osório et al, 2008) is a self-report instrument that aims to measure the self-perception of performance in the specific situation of public speaking. It is based upon cognitive theories that propose that social anxiety is the result of a negative perception of oneself and of others towards oneself. The scale is comprised of 10 items, rated on a likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), which are organized into two subscales of five items each, for positive or negative self-evaluation. In this study, we applied the negative self-evaluation subscale (SSPS-N).

The Bodily Symptoms Scale (BSS) was designed to detect physical symptoms that can, indirectly, influence anxiety measures (Zuardi et al, 1993). It is organized into 21 items, and the intensity of each symptom is rated from 0 (no symptom) to 5 (highest).

Physiological Measurements

Skin conductance

A computer-controlled, voltage-constant (0.6 V) module with automatic back off (Contact Precision Instruments, UK) measured skin conductance. Two electrodes (Beckman, UK) were fixed with adhesive tape. Contact with the skin was made through high conductance gel (KY gel, Johnson and Johnson, Brazil). The skin conductance level (SCL) and the number of spontaneous fluctuations (SF) of the skin conductance were recorded.

Arterial blood pressure

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured by a mercury sphygmomanometer (Becton Dickinson, Brazil).

Heart rate

Heart rate (HR) was estimated by manually counting the pulse rate.

Procedure

The SPST was the same as used by McNair et al (1982) with some modifications (Hallak et al, 2010).

The procedure is summarized in Table 1. After a 15-min adaptation period, baseline measurements (B) were taken and followed by a single dose of oral CBD or placebo in a double-blind procedure. Pretest measurements (P) were made 80 min after the drug ingestion. Immediately thereafter, the subject received the instructions and had 2 min to prepare a 4-min speech about ‘the public transportation system of your city'. He/she was also told that the speech would be recorded on videotape and later analyzed by a psychologist. Anticipatory speech measurements (A) were taken before the subject started speaking. Thus, the subject started speaking in front of the camera while viewing his/her own image on the TV screen. The speech was interrupted in the middle and speech performance measurements (S) were taken. The speech was recorded for a further 2 min. Post-test measurements (F1 and F2) were made 15 and 35 min after the end of the speech, respectively.

Table 1. Timetable of the Experimental Session.

| Session (min) | Phase | Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| −0:30 | Adaptation to the laboratory; instructions about the interview and measurements | |

| −0:15 | Baseline (B) | SCL, SF, HR, AP, VAMS, SSPS and BSS |

| 0 | Drug intake: CBD or placebo capsules | |

| +1:20 | Pre-stress (P) | SCL, SF, HR, AP, VAMS, SSPS and BSS |

| +1:30 | Instructions about the SPST | |

| +1:32 | Speech preparation | |

| +1:34 | Anticipatory speech (A) | SCL, SF, HR, AP, VAMS, SSPS and BSS |

| +1:45 | Start of speech | |

| +1:47 | Speech performance (S) | SCL, SF, HR, AP, VAMS, SSPS and BSS |

| +1:53 | Continuation of speech | |

| +1:55 | End of speech | |

| +2:10 | Post-stress 1 (F1) | SCL, SF, HR, AP, VAMS, SSPS and BSS |

| +2:30 | Post-stress 2 (F2) | SCL, SF, HR, AP, VAMS, SSPS and BSS |

Statistical Analysis

Clinical and demographical characteristics were analyzed with the non-parametric tests (gender and socioeconomic level) and by the analysis of variance for one factor (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc Bonferroni's test for multiple comparisons (age, age of SAD onset and SPIN).

Scores of VAMS's factors, SSPS-N, BSS, arterial diastolic and systolic pressure, heart rate, as well as the SCL and the total number of SF, were transformed by calculating the difference between the score in each phase and the pretest score in the same volunteer. For the analysis, SCL values were converted into natural logarithms (logn). These delta scores were submitted to a repeated-measures analysis of variance (repeated-measures ANOVA), analyzing the factors of phases, groups, and phases by groups' interaction. In the case where sphericity conditions were not reached, the degrees of freedom of the repeated factor were corrected with the Huynh–Feldt epsilon. Whenever a significant phase by group interaction occurred, comparisons among the groups were made at each phase using a one-factor ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni's test.

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS-17 program, and the significance level adopted was p<0.05.

RESULTS

Subjects

The clinical and demographical characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 2. The only significant differences among the groups were found in the mean scores of SPIN (F2, 35=34.3; p<0.001). The SPIN scores were significantly lower in healthy volunteers than in subjects with SAD who received CBD or placebo. No significant difference was observed between the two groups with SAD.

Table 2. Clinical and Demographical Characteristics of the Groups.

| Sad-placebo | Sad-cbd | Healthy | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 6/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 1.0 |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 22.9 (2.4) | 24.6 (3.6) | 23.3 (1.7) | 0.36 |

| Socioeconomic levelsa (Median) | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | 0.66 |

| Age of SAD onset (mean (SD)) | 12.2 (5.8) | 9.6 (6.9) | — | 0.36 |

| SPIN (mean (SD)) | 36.3 (11.2) | 30.9 (12.0) | 5.75 (3.3) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: SAD, social anxiety disorder; SPIN, Social Phobia Inventory.

Socioeconomic levels were assessed by the Brazil Socioeconomic Classification Criteria.

Psychological Measures

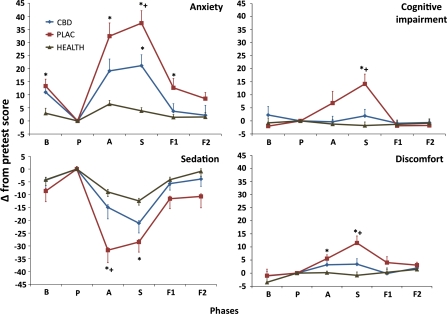

No differences were observed among the initial measures of the three groups on anxiety (F2,35=1.4; p=0.27), sedation (F2,35=0.4; p=0.70), cognitive impairment (F2,35=1.9; p=0.16), and discomfort (F2,35=0.6; p=0.55) VAMS factors. Changes in relation to the pretest phase of VAMS factors in the three groups are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Changes in Visual Analogue Mood Scale (VAMS) factors induced by simulated public speaking test (SPST), measured in 12 social anxiety patients who received cannabidiol ( ), 12 social anxiety patients who received placebo (

), 12 social anxiety patients who received placebo ( ) and 12 healthy controls (

) and 12 healthy controls ( ). The phases of the experimental session are: b, basal; P, pretest; a, anticipation; S, speech performance; F1, post-speech measures 1; F2, post-speech measures 2. Points in the curves indicate mean and vertical bars SEM. *Indicates significant differences from healthy control and + from social anxiety patients who received cannabidiol.

). The phases of the experimental session are: b, basal; P, pretest; a, anticipation; S, speech performance; F1, post-speech measures 1; F2, post-speech measures 2. Points in the curves indicate mean and vertical bars SEM. *Indicates significant differences from healthy control and + from social anxiety patients who received cannabidiol.

Regarding the VAMS anxiety factor, the repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of phases (F3.6,118.5=32.7; p<0.001), group (F2,33=13.5; p<0.001) and phases by group interaction (F7.2,118.5=6.4; p<0.001). Comparisons among the groups evidenced significant differences between SAD-PLAC and HC at the initial (p=0.018), anticipatory (p<0.001), speech (p<0.001) and post-speech (0.018) phases. The SAD-CBD differs from the SAD-PLAC (p=0.012) and HC (p=0.007) during the speech phase. Regarding cognitive impairment, repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of phases (F3.2,105.8=5.6; p=0.001) and phases by group interaction (F6.4,105.8=5.1; p<0.001). Comparisons among the groups evidenced that SAD-PLAC differed significantly from SAD-CBD (p=0.009) and HC (p=0.001) at the speech phase. Regarding discomfort, there are significant effects of phases (F4,132=7.1; p<0.001), group (F2,33=4.7; p=0.016) and phases by group interaction (F4,132=2.2; p=0.036). Comparisons among the groups evidenced that SAD-PLAC differed significantly from HC at the anticipatory phase (p=0.047) and from SAD-CBD (p=0.029) and HC (p=0.001) at speech phases. On the sedation factor, there are significant effects of phases (F3.1,102.1=27.1; p<0.001), group (F2,33=5.3; p=0.010) and phases by group interaction (F6.2,102.1=2.4; p=0.032). Comparisons among the groups evidenced that SAD-PLAC differed significantly from SAD-CBD (p=0.016) and HC (p=0.001) at the anticipatory phase and from HC at speech phases (p=0.005).

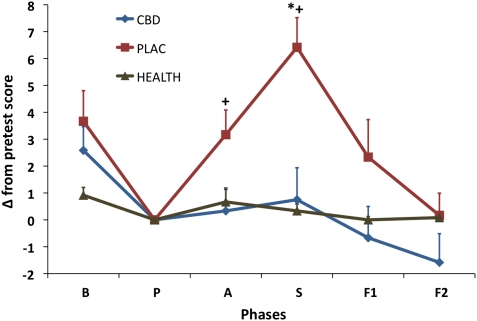

The scores of the SSPS-N at the initial phase differ significantly among the groups (F2,35=14.8; p<0.001), with the SAS-PLAC and SAD-CBD higher than HC (p<0.001). Changes in relation to the pretest phase of SSPS-N in the three groups are shown in Figure 2. The repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of phases (F3.1,101.6=9.7; p<0.001), group (F2,33=6.6; p=0.004) and phases by group interaction (F6.2,101.6=3.2; p=0.006). Comparisons among the groups evidenced significant differences between SAD-PLAC and SAD-CBD at the anticipatory (p=0.043) and speech (p=0.001) phases and between SAD-PLAC and HC at the speech (p<0.001) phases. No significant differences were observed between SAD-CBD and HC.

Figure 2.

Changes in SSPS-N scores induced by simulated public speaking test (SPST). Other specifications are in the legend of Figure 1. *Indicates significant differences from healthy control and + from social anxiety patients who received cannabidiol.

No differences were observed among the initial measures of the three groups on BSS (F2,35=1.4; p=0.25). Changes in relation to the pretest phase of BSS in the three groups showed a significant effect of phases (F3.3,110.2=8.1; p<0.001) and phases by group interaction (F6.7,110.2=2.3; p=0.035). Comparisons among the groups evidenced significant differences between SAD-PLAC and HC at the speech phase (p=0.05). In this phase the changes in relation to the pretest phase were 8.2 for SAD-PLAC and 0.3 for HC. SAD-CBD group had an intermediate score, which did not differ from SAD-PLAC or HC.

The observed powers for the tests used in the statistical analysis of the anxiety VAMS factor and in the negative SSPS, were 0.996 and 0.881, respectively.

Physiological Measures

Systolic pressure (F2,35=1.159; p=0.33), diastolic pressure (F2,35=1.7; p=0.20), heart rate (F2,35=0.4; p=0.67), SCL (F2,5=1.6; p=0.22), and SF (F2,35=0.1; p=0.90) did not show significant differences among the three groups in the initial measures. Changes in relation to the pretest showed significant repeated-measures ANOVA effect only in phases for the following physiological measures: systolic pressure (F3.7,122.5=5.9; p<0.001), diastolic pressure (F4,132=5.1; p<0.001), SCL (F3.2,84.9=2.8; p=0.045), and SF (F3.6,92.4=3.8; p=0.009). In these measures, the values were significantly elevated during SPS without differences among the groups. For the heart rates, the repeated-measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of phases (F3.9,127.1=6.9; p<0.001) and phases by group interaction (F7.7,127.1=4.6; p<0.001). Comparisons among the groups showed a reduction in heart rates from the initial to the pretest measures significantly greater (p<0.001) for the SAD-PLAC (delta mean=9.17; SE=1.77) than for HD (delta mean=0.5; SE=0.56) group. The SAD-CBD group (delta mean=4.3; SE=1.56) did not differ significantly from the other two groups.

DISCUSSION

As observed in another study of SAD patients' performance on SPST (Crippa et al, 2008b), the present results of the VAMS scale showed that the SAD-PLAC group presented a significantly higher anxiety level and greater cognitive impairment, discomfort, and alert compared with the control group during the test. This was expected as the fear of speaking in public is a cardinal manifestation of SAD (Brunello et al, 2000).

Pretreatment of SAD patients with CBD significantly reduced anxiety, cognitive impairment, and discomfort in their speech performance (S) and significantly decreased alert in their anticipatory speech (A). The cognitive impairment, discomfort, and alert of SAD patients that received CBD had similar results to the HC during the SPST. These preliminary results indicate that a single dose of CBD can reduce the anxiety-enhancing effect provoked by SPST in SAD patients, indicating that this cannabinoid inhibits the fear of speaking in public, one of the main symptoms of the disorder.

The anxiolytic effects of CBD had been extensively demonstrated in animal studies and in healthy volunteers submitted to anxiety induced by several procedures, including the simulation of public speaking (Crippa et al, 2010, 2011). However, there is only one published report of the anxiolytic effect of CBD in an anxiety disorder (Crippa et al, 2010, 2011). This study was performed with SAD patients and the anxiolyic effects of CBD were detected before provoking anxiety by the tracer injection and scanning procedure of SPECT, suggesting that CBD facilitates habituation of anticipatory anxiety. The SPECT analysis of this study and of a previous one with healthy volunteers (Crippa et al, 2004) showed that the CBD effects were associated with the activity of the parahippocampal gyrus and hippocampus. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) detected attenuated responses in the amygdala and in the cingulated cortex induced by CBD (600 mg) during the viewing of fearful facial stimuli (Fusar-Poli et al, 2009a). Moreover, CBD has shown to disrupt forward intrinsic connectivity between the amygdala and the anterior cingulate during the neural response to fearful faces (Fusar-Poli et al, 2009b). Taken together, these studies demonstrate the action of CBD in limbic and paralimbic brain areas, which are known to be associated with anxiety.

The anxiolytic action of CBD may be mediated by 5-HT1A receptors, as it displaces the agonist [3H]8-OHDPAT from the cloned human 5-HT1A receptor in a concentration-dependent manner and exerts an effect as an agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptor in signal-transduction studies (Russo et al, 2005). Additionally, CBD injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats produced anxiolytic-like effects in the elevated plus-maze and elevated T-maze, and these effects were prevented by a 5HT1A receptor antagonist (Soares et al, 2010; Campos and Guimaraes, 2008).

Another important observation of this study was that the increase of negative self-evaluation during public speaking was almost abolished by CBD. In a previous study, we suggested that the negative self-evaluation during the phobic situation of public speaking would be important for the avoidance and impairment in social functioning that support the diagnosis of SAD (Freitas-Ferrari et al, submitted). In that way, the observed effect of CBD for improving the self-evaluation during public speaking, which is one of the pivotal aspects of SAD, will influence the therapy of SAD patients.

Although physiological measures have not shown significant differences among the groups, the self-report of somatic symptoms (BSS) increased significantly only for the SAD patients who received placebo during the test. Following the same rationale as above, it is well-known that more pronounced bodily symptoms may contribute to the clinical diagnosis of SAD, and this result suggests that CBD also protects the patients from their subjective physiological abnormalities induced by the SPST.

The findings reported herein need to be interpreted with caution, given the limitations of the study. First, it would have been desirable to measure plasma levels of CBD and to relate such measurements to changes in the VAMS scores; however, it should be pointed out that previous investigations have not been able to confirm whether there is a direct relationship between plasma levels of cannabinoids, in particular CBD, and their clinical effects (Agurell et al, 1986). Another limitation refers to the size of the sample included; however, the statistical power of the data from the VAMS and SSPS was shown to be relatively robust even with small subject numbers.

An extensive list of medications for the pharmacological treatment of SAD was made available in recent years, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI), antidepressants and benzodiazepines (Schneier, 2001). However, both SSRIs and SSNRIs have an initial activation and a long latency period of response, and benzodiazepines are limited by their potential to produce motor impairment, sedation, and to induce dependence and withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation (Blanco et al, 2002). Conversely, CBD has important advantages in comparison with the currently available pharmacological agents for the treatment of SAD, such as an early onset of action and lack of important side effects both with acute and chronic administration to healthy subjects (Crippa et al, 2010, 2011). Moreover, it was shown that repeated treatment with CBD (but not 9-THC) does not develop tolerance or dependence (Hayakawa et al, 2007) and possibly reduces drug-seeking behaviors (Parker et al, 2004; Ren et al, 2009; Morgan et al, 2010). Thus, because of the absence of psychoactive or cognitive effects, to its safety and tolerability profiles, and to its broad pharmacological spectrum, CBD is possibly the cannabinoid that is most likely to have initial findings in anxiety translated into clinical practice.

Therefore, the effects of a single dose of CBD, observed in this study in the face of one of the main SAD's phobic stimuli, is a promising indication of a rapid onset of therapeutic effect in patients with SAD. However, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trials with larger samples and chronic use are still needed to confirm these statements. Likewise, because CBD effects are biphasic, the determination of adequate treatment ranges for each disorder remains a challenge. Further research to determine the precise mechanisms of action of CBD in the different anxiety disorders is desirable and opportune.

Acknowledgments

This work received grants from FAPESP. FK, JQ, RR, AEN, JECH, AWZ and JASC are recipients of CNPq Productivity Awards.

Professor Kapczinski has received grant/research support from Astra-Zeneca, EliLilly, the Janssen-Cilag, Servier, CNPq, CAPES, NARSAD and the Stanley Medical Research Institute; he has been a member of the speakers' boards for Astra-Zeneca, EliLilly, Janssen and Servier; and he has served as a consultant for Servier.

References

- Agurell S, Carlsson S, Lindgren JE, Ohlsson A, Gillespie H, Hollister L. Interactions of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol with cannabinol and cannabidiol following oral administration in man. Assay of cannabinol and cannabidiol by mass fragmentography. Experientia. 1981;37:1090–1092. doi: 10.1007/BF02085029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agurell S, Halldin M, Lindgren JE, Ohlsson A, Widman M, Gillespie H, et al. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids with emphasis on man. Pharmacol Rev. 1986;38:21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Antia SX, Liebowitz MR. Pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgwardt SJ, Allen P, Bhattacharyya S, Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Seal ML, et al. Neural basis of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol: effects during response inhibition. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunello N, den Boer JA, Judd LL, Kasper S, Kelsey JE, Lader M, et al. Social phobia: diagnosis and epidemiology, neurobiology and pharmacology, comorbidity and treatment. J Affect Disord. 2000;60:61–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small JW, Schlauch RC, Lewinsohn PM. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos AC, Guimaraes FS. Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Psychiatric Association Clinical practice guidelines. Management of anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatryi. 2006;51 (Suppl 2:9–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas MH, Nardi AE, Manfro GG, Hetem LA, Andrada NC, Levitan MN, et al. Guidelines of the Brazilian medical Association for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of social anxiety disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32:444–452. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010005000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Foa E, Weisler RH. Psychometric properties of Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:379–386. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, Katzelnick D, Davidson JR. Mini-Spin: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:137–140. doi: 10.1002/da.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, de Lima Osrio F, Del-Ben CM, Filho AS, da Silva Freitas MC, Loureiro SR. Comparability between telephone and face-to-face structured clinical interview for DSM-IV in assessing social anxiety disorder. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2008a;44:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Derenusson GN, Ferrari TB, Wichert-Ana L, Duran F, Marti N-Santos RO, et al. Neural basis of anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in generalized social anxiety disorder—a preliminary report. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:121–130. doi: 10.1177/0269881110379283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Loureiro SR, Baptista CA, Osório F. Are there differences between early- and late-onset social anxiety disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;29:195–196. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462007000200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Busatto GF, Santos-Filho A, Graeff FG, Borduqui T, et al. 2008bGrey matter correlates of cognitive measures of the simulated public speaking test in social anxiety spectrum: a voxel-based study Eur Psychiatry 23(Suppl 221218166402 [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Garrido GE, Wichert-Ana L, Guarnieri R, Ferrari L, et al. Effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on regional cerebral blood flow. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:417–426. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Hallak JE. Therapeutical use of the cannabinoids in psychiatry. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32 (Suppl 1:S56–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Martín-Santos R, Bhattacharyya S, Atakan Z, McGuire P. Cannabis and anxiety: a critical review of the evidence. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:515–523. doi: 10.1002/hup.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Osório F, Crippa JA, Loureiro SR. A study of the discriminative validity of a screening tool (MINI-SPIN) for social anxiety disorder applied to Brazilian university students. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima Osório F, Crippa JA, Loureiro SR. Self statements during public speaking scale (SSPS): cross-cultural adaptation for Brazilian Portuguese and internal consistency. Rev Psiq Clín. 2008;35:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Ben CM, Vilela JAA, Crippa JAS, Hallak JEC, Labate CM, Zuardi AW. Confiabilidade teste-reteste da Entrevista Clínica Estruturada para o DSM-IV—Versão Clínica (SCID-CV) traduzida para o português. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2001;23:156–159. [Google Scholar]

- Filho AS, Hetem LA, Ferrari MC, Trzesniak C, Martín-Santos R, Borduqui T, et al. Social anxiety disorder: what are we losing with the current diagnostic criteria. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Clinican Version (SCID-CV) American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Allen P, Bhattacharyya S, Crippa JA, Mechelli A, Borgwardt S, et al. Modulation of effective connectivity during emotional processing by Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009a;13:421–432. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Bhattacharyya S, Borgwardt SJ, Allen P, Martin-Santos R, et al. Distinct effects of {delta}9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on neural activation during emotional processing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009b;66:95–105. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff FG, Parente A, Del-Ben CM, Guimarães FS. Pharmacology of human experimental anxiety. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:421–432. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Nozako M, Ogata A, Hazekawa M, Liu AX, et al. Repeated treatment with cannabidiol but not Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol has a neuroprotective effect without the development of tolerance. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1079–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallak JE, Crippa JA, Quevedo J, Roesler R, Schröder N, Nardi AE, et al. National science and technology institute for translational medicine (INCT-TM): advancing the field of translational medicine and mental health. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32:83–90. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann SG, Di Bartolo PM. An instrument to assess self-statements during public speaking: scale development and preliminary psychometric properties. Behav Ther. 2000;31:499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(00)80027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The global burden of anxiety and mood disorders: putting the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) findings into perspective. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 (Suppl 2:10–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Frankenthaler LM, Czerlinsky T, White TW, Sasson S, Fisher S. Simulated public speaking as a model of clinical anxiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;77:7–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00436092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Lecrubier Y, Baldwin DS, Kasper S, Lader M, Nil R, et al. European college of neuropsychopharmacology. ECNP Consensus Meeting, March 2003. Guidelines for the investigation of efficacy in social anxiety disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Freeman TP, Schafer GL, Curran HV. Cannabidiol attenuates the appetitive effects of Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in humans smoking their chosen cannabis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1879–1885. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris H. The action of sedatives on brain stem oculomotor systems in man. Neuropharmacology. 1971;10:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(71)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osório Fde L, Crippa JA, Loureiro SR. Further study of the psychometric qualities of a brief screening tool for social phobia (MINI-SPIN) applied to clinical and nonclinical samples. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2010;46:266–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente ACBV, Garcia-Leal C, Del-Ben C, Guimarães FS, Graeff FG. Subjective and neurovegetative changes in health volunteers and panic patients performing simulated public speaking. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Burton P, Sorge RE, Yakiwchuk C, Mechoulam R. Effect of low doses of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on the extinction of cocaine-induced and amphetamine-induced conditioned place preference learning in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175:360–366. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1825-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Whittard J, Higuera-Matas A, Morris CV, Hurd YL. Cannabidiol, a nonpsychotropic component of cannabis, inhibits cue-induced heroin seeking and normalizes discrete mesolimbic neuronal disturbances. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14764–14769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4291-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK. Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR. Treatment of social phobia with antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 (Suppl 1:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares VDEP, Campos AC, Bortoli VC, Zangrossi H, Jr, Guimarães FS, Zuardi AW. Intra-dorsal periaqueductal gray administration of cannabidiol blocks panic-like response by activating 5-HT1A receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2010;213:225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW. Cannabidiol: from an inactive cannabinoid to a drug with wide spectrum of action. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30:271–280. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Cosme RA, Graeff FG, Guimarães FS. Effects of ipsapirone and cannabidiol on human experimental anxiety. J Psychopharmacol. 1993;7:82–88. doi: 10.1177/026988119300700112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Karniol IG. Transcultural evaluation of a self-evaluation scale of subjective states. J Brasileiro Psiquiatr. 1981;131:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- Zuardi AW, Shirakawa I, Finkelfarb E, Karniol IG. Action of cannabidiol on the anxiety and other effects produced by delta 9-THC in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;76:245–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00432554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]