Abstract

The relative contribution of norovirus to disease burden on society has only recently been established and they are now established as a major cause of gastroenteritis in the developed world. However, despite the medical relevance of these viruses, an efficient in vitro cell culture system for human noroviruses has yet to be developed. As a result, much of our knowledge on the basic mechanisms of norovirus biology has come from studies using other members of the Caliciviridae family of small positive stranded RNA viruses. Here we aim to summarise the recent advances in the field, highlighting how model systems have played a key role in increasing our knowledge of this prevalent pathogen.

Keywords: Norwalk virus, calicivirus, gastroenteritis, antiviral, animal models, PPMO, Ribavirin

Introduction

Gastroenteritis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, resulting in approximately 5 to 8 million deaths per annum [1]. Gastroenteritis can be caused by a number of organisms, including many viruses and bacterial pathogens, however viruses pose a particular problem due to the limited number of antiviral therapies available for treatment. Over the past decade it has become evident that members of the Norovirus and Sapovirus genera of the Caliciviridae family of small positive stranded RNA viruses are responsible for the majority of viral gastroenteritis cases in the developed world [2; 3; 4]. Studies in Europe have estimated that human noroviruses are responsible for up to 85% of all food born outbreaks of gastroenteritis [5]. Classically, human noroviruses are not associated with significant mortality [6]. Recently however, human noroviruses have been linked to a range of more serious conditions such as necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in neonates [7] and seizures [8]. In addition, an active role for noroviruses in diarrhoea-related deaths in the developing world has been suggested/implicated (at present this remains unsubstantiated, mainly because of poor or non-existent epidemioligcal disease surveillance) [9].

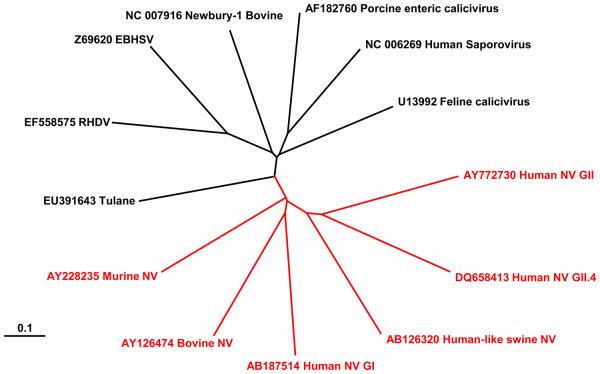

Although Norwalk virus (NV), the prototype human norovirus, was discovered as the causative agent of a gastroenteritis outbreak in an elementary school in Norwalk, USA, in 1968 [10], despite several efforts, the establishment of an in vitro cultivation of these highly contagious human viruses has failed up to this day. As a result, progress on the study of human norovirus pathogenesis and the molecular mechanisms used for viral genome translation and replication has lagged behind that of many related positive stranded RNA viruses. The use of model systems has greatly facilitated the study of caliciviruses in general, which in turn has lead to a greater understanding of norovirus biology. The phylogenetic relatedness of members of the Caliciviridae is highlighted in figure 1 and table 2 demonstrating that many animal viruses are genetically closely related to human noroviruses. In the following review we aim to summarise progress in the area, highlighting in particular how the use of model systems, particularly animal caliciviruses, has aided our current understanding of norovirus biology and the future potential of these model systems.

Figure 1.

A radial tree phylogram (Saitou and Nei neighbour joining algorithm) comparing the entire genome sequences of 13 members of the Caliciviridae family (highlighted red; Norovirus genus, highlighted black; all other genera). Branch lengths are proportional to the degree of divergence between the sequences. A distance scale representing nucleotide substitutions per position is shown. Accession numbers are indicated. RHDV; rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus, EBHSV; European brown hare syndrome virus, NV; norovirus. Sequences were aligned using the Vector Nti AlignX software (Invitrogen). The radial tree was plotted using the TreeView freeware.

Table 2.

Identity matrix for caliciviruses.

| GII NV (Hu) | GII.4 NV (Hu) | GI NV (Hu) | BNV | MNV | Tulane | RHDV | EBHSV | Newbury1 Bovine |

PEC | Saporovirus | FCV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swine NV (Hu-like) |

66 | 66 | 55 | 54 | 53 | 41 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 32 | 36 | 33 |

| GII NV (Hu) | 74 | 54 | 53 | 52 | 42 | 38 | 39 | 33 | 33 | 36 | 33 | |

| GII.4 NV (Hu) | 55 | 54 | 52 | 42 | 39 | 39 | 33 | 34 | 36 | 33 | ||

| GI NV (Hu) | 60 | 51 | 42 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 34 | 36 | 32 | |||

| BNV | 51 | 42 | 39 | 38 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 33 | ||||

| MNV | 40 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 32 | |||||

| Tulane | 38 | 39 | 33 | 35 | 37 | 36 | ||||||

| RHDV | 71 | 44 | 39 | 45 | 39 | |||||||

| EBHSV | 44 | 39 | 44 | 39 | ||||||||

| Newbury1 Bovine |

38 | 40 | 37 | |||||||||

| PEC | 53 | 39 | ||||||||||

| Saporovirus | 40 | |||||||||||

| FCV |

Percentage nucleotide identity of the full-length genome is presented. Hu; human, BNV; bovine norovirus, MNV; murine norovirus, RHDV; rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus, EBHSV; European brown hare syndrome virus, PEC; porcine enteric calicivirus, FCV; feline calicivirus, G*; genogroup, NV; Norovirus

Norovirus cultivation in vitro

The inability of human noroviruses to be propagated efficiently in tissue culture has hampered the study of noroviruses and significantly delayed research to understand the viral replication cycle, mechanisms of viral virulence as well as the development of antiviral drugs. The first insight into the pathophysiology of these viruses was delivered by some extensive studies using healthy human volunteers. In 1971, Dolin et al. demonstrated that the agent of the acute infectious gastroenteritis outbreak from Norwalk could be transmitted to volunteers by oral administration of filtrated bacteria-free stool filtrates [11]. Recent work has also highlighted the use of experimental human infection to determine the shedding rates [12]. It is notable that NV was the first viral gastroenteritis agent to be identified. Soon after, the remaining three groups of viruses causing gastroenteritis were discovered such as astroviruses [13], enteric adenoviruses [14] and rotaviruses [15]. A subsequent volunteer study demonstrated that the Norwalk agent was a small, heat-stable and non-enveloped virus [16].

Numerous attempts to cultivate human noroviruses in tissue culture using traditional methods have yet to yield an efficient cell culture system. The last published experimental approach to develop a routine cell culture system for human noroviruses also failed [17]. Human gastrointestinal epithelial cells as well as other human and animal tissues were tested and shown to be resistant to successful virus propagation (A549, AGS, Caco-2, CCD-18, CERFK, CR-PEC, Detroit 551, Detroit 562, FRhK-4, HCT-8, HeLa, HEC, Hep-2,n Ht-29, HuTu-80, I-407, IEC-6, IEC-18, Kato-3, L20B, MA104, MDBK, MDCK, RD, TMK, Vero and 293). Furthermore, the induction of cell differentiation with substances like insulin, DMSO or butyric acid, the addition of numerous bioactive digestive enzymes, the use of various inoculum preparation techniques and inoculation methods or the variation of the virus genotypes used for the infection were all unsuccessful [17]. However, recently published data have demonstrated that the transfection of human hepatoma Huh-7 cells with NV RNA isolated from stool samples of human volunteers resulted in virus replication, viral antigen expression and production of progeny virus particles indicating that the viral RNA is infectious [18]. The observations that the replication of transfected NV RNA in Huh-7 cells led to a single cycle but the newly synthesised viruses were not able to infect other cells suggests that the missing factor(s) required for norovirus cultivation in vitro might be associated with viral entry (i.e. receptor binding or genome uncoating) [18].

Since the cells of the virus infected tissues/organs grow in a three dimensional (3D) milieu in vivo and, compared to the standard tissue culture conditions, the cells are in a more differentiated state, one possible explanation for the inability of noroviruses to grow in tissue culture is that the cells lack specific factors or features which are only evident during true differentiation e.g. true apical and basolateral polarisation of the cell. This hypothesis was tested in a recently published study by infecting a 3D organoid tissue culture model of human small intestinal epithelium (INT-407) with human norovirus isolated from human stool samples [19]. The 3D INT-407 cell culture was originally developed for the pathogenesis study of Salmonella enteritica [20]. Cell cultivation occurs in cell suspension in a rotating-wall vessel which is optimised to minimise cell damage on cell aggregates allowing the formation and differentiation of cells in 3-dimensional structures [21; 22]. Using this model, Straub et al. established, for the first time, an in vitro cell culture system which, data suggested, can be infected by human genogroup I and II noroviruses. The infected cells displayed cytopathic effect exhibiting vacuolisation and shortening of microvillus. Furthermore, the production of particles whose size corresponded to that of human noroviruses could also be identified in the infected cultures. PCR and in situ hybridisation experiments revealed the presence of the viral RNA over 5 cell passages, although whether or not this represented newly synthesised viral RNA or maintenance of input virus was not clear. Similarly to human noroviruses, the 3-D organoid model was also successfully used for the production of infectious particles of another fastidious agent, the hepatitis C virus [23]. However, the crucial factor which enables the infection of the cells grown in the 3D organoid model remains still to be identified. For example it is possible that the cells grown in the 3D culture expose some molecules (ie. receptor/co-receptor) for the virus infection in a more correct conformation allowing the virus to spread in culture. It is also notable that the Lewis A antigen has been demonstrated to be present on the cell surface in the 3-D system [20] providing further evidence that the Lewis antigens together with the ABH histo-blood group antigens play an important role in the attachment or entry of the virus [24]. The above mentioned 3D model seems to be very promissing, however additional validation is required. In addition there are further complications; the method is costly, technically demanding and requires specialist equipment.

Another available tool for the investigation of virus-host interactions or for testing potential antiviral drugs is the use of a viral replicon system. Viral replicons are self-replicating RNAs which are maintained in cell lines via selection of a drug resistance marker inserted into the viral RNA genome. Using human Huh-7 or hamster BHK-21 cells, Chang et al. succeeded in generating a stable replicon system for NV [25]. These cells were proved to stably express the self-replicating NV RNA along with the NV proteins over multiple passages. The manipulated NV replicon RNA encodes the neomycin resistance gene in place of the major capsid protein VP1, allowing the selection for cells expressing replicon RNA with G418. Using the NV replicon system, various potential antiviral molecules, described in more detail below, have been identified such as interferon alpha [25], interferon gamma, ribavirin [26] or peptide-conjugated phosphorodiamidiate morpholino oligomers (PPMOs) directed against the 5′-end of the noroviral genome [27].

In addition to the replicon system, a further valuable model for the study of virus-host interactions is the generation of recombinant virus-like particles (VLP). Human norovirus VLPs have been generated by the expression of the viral major capsid protein (VP1) with or without the minor capsid protein (VP2). The expressed proteins self assemble to form VLPs which appear to retain all the morphological characteristics of authentic virions. Most frequently, the viral capsid proteins have been expressed in insect cells using baculovirus expression systems [28; 29], however, VLPs have been also generated in human cells by either direct transfection [30] or the use of viral replicons [31], and also in plants such as tomato [32] or potato [33]. The use of human norovirus VLPs has markedly facilitated studies focusing on the identification of protein-protein interactions between host and virus. Using recombinant human norovirus VLPs, it has been shown that human noroviruses bind to ABO histo-blood group antigens from secretor individuals (For example: [34; 35]). Furthermore, as the antigenic features of VLPs are similar to those of the native virus particles, the use of VLPs may serve as a good model for immunology studies or the development of diagnostic assays or vaccines. For example, the VLPs generated in tomato fruit were shown to stimulate excellent IgG and IgA responses against Norwalk virus capsid protein when fed to mice [32] while the VLPs generated in potato resulted in a modest immune response in human volunteers [33].

As described in more detail below, studies with animal noroviruses/caliciviruses have served as valuable models for our understanding of the biology of human noroviruses. Animal caliciviruses amenable to in vitro cultivation are summarised in table 1, with their genetic relatedness illustrated in figure 1 and table 2. The lately discovered murine norovirus (MNV) is the only norovirus which can be efficiently propagated in vitro [36]. MNV was shown to have a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages allowing its routine propagation in RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cells [37]. The fact that a small animal model is also available for MNV makes this virus one of the most competent models for human norovirus studies. Furthermore, there are other animal caliciviruses, ie. feline calicivirus (FCV) or porcine enteric calicivirus (PEC), which can also be propagated under laboratory conditions. FCV strains can be routinely cultivated in Norden Laboratories Feline Kidney cells (NLFK) or feline kidney cells (CRFK) while a PEC strain, namely Cowden, was shown to be propagated in a porcine kidney continuous cell line (LLC-PK) in the presence of bile acids [38].

Table 1.

Potential animal pathogenicity models for human noroviruses

| Virus | Genus | Disease * | Host | Tissue Culture growth? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GII NV (Hu) AY772730 |

Norovirus | Gastroenteritis | Human | no |

| GII.4 NV (Hu) DQ658413 |

Norovirus | Gastroenteritis | Human | no |

| GI NV (Hu) AB187514 |

Norovirus | Gastroenteritis | Human | no |

| Swine NV (Hu-like) AB126320 |

Norovirus | Asymptomatic | Porcine | no |

| BNV AY126474 |

Norovirus | Asymptomatic | Bovine | no |

| MNV AY228235 |

Norovirus | Systemic disease in immunocompromised mice/ asymptomatic |

Murine | yes (murine macrophages) |

| Tulane EU391643 |

“Recovirus” | Not known | Rhesus macaques | yes (monkey kidney cells) |

| RHDV EF558575 |

Lagovirus | Hemorrhagic | Rabbits | yes (baby hamster kidney cells) |

| EBHSV Z69620 |

Lagovirus | Hemorrhagic | Hares | no |

| Newbury1 Bovine NC_007916 |

“Becovirus/

Nabovirus” |

Gastroenteritis | Bovine | no |

| PEC AF182760 |

Sapovirus | Gastroenteritis | Porcine | yes (Cowden strain) porcine kidney cell line |

| Saporovirus NC_006269 |

Sapovirus | Gastroenteritis | Humans | no |

| FCV U13992 |

Vesivirus | Respiratory infections/ virulent systemic disease |

Cats | yes (feline kidney cortex cells) |

Animal viruses are shaded.

denotes dominant published or reported disease.

Models for norovirus pathogenesis

The aforementioned difficulties associated with in vitro cultivation of human noroviruses, combined with imperfect cell-culture systems that can never accurately recreate the ‘complete immunological back-drop’ for infection, collectively demonstrate the absolute requirement for in vivo (animal) models in norovirus research. In fact such models for human noroviruses are both readily abundant and in use. First and foremost in terms of relevance are humans themselves. A significant amount of experimental research into the disease has been carried out in volunteers [39] examples: [40; 33] however, the expenses involved and difficulties associated with sampling (both in terms of taking the samples e.g. invasive biopsies during a short acute phase, and handling the samples e.g. bio-containment issues for the virus) have somewhat limited such approaches.

Basic methods of sampling from the natural human hosts are relatively common. Faeces and sera are routinely available providing critical data for researchers studying a wide range of fields such as disease symptoms, persistence and recovery [12]; the immune response to infection [41; 42]; the development of diagnostics [reviewed in 43] and epidemiological factors pertaining to genotype and strain prevalence [44; 45]. For instance, a critical examination of norovirus susceptibility in patients (highlighted by the apparent natural immunity of a sub-set of the human population to infection by particular strains of noroviruses) was the initial catalyst behind the identification of resistance markers in the human population (associated with HBGA blood groups) and the elucidation of immune selection mechanisms responsible for the persistence of GII.4 noroviruses in human populations [46]. Recently researchers have shown, through investigation of duodenal biopsies, some of the mechanisms responsible for diarrhoea in humans [47]. In addition, the human host still represents the only ready source of live virus.

The limitations of humans as a model system are numerous:

Experimentation is difficult and expensive,

Sampling is restricted and technically demanding,

Bio-containment requirements for the live and highly infectious virus,

Ability to study live virus is reduced by the lack of a tissue culture system.

To summarise, humans clearly represent the most accurate model for studying human norovirus pathogenesis, especially with regards to epidemiological and medical research. Realistically however, to study aspects of the virus such as immunology, pathogenesis, as well as the molecular replication cycle it is necessary that other models are used.

The candidates for alternative in vivo models are either those animals closely related to humans or indeed those viruses closely related to noroviruses i.e. other members of the Caliciviridae (Table 1). Apart from the sapoviruses which also infect humans, other caliciviruses infect a wide range of mammalian hosts [48]. The suitability and use of these alternative models for human norovirus research are summarised below:

Non-human primates and the recently discovered Tulane virus – An obviously attractive model for human norovirus infection are the non-human primates. Experimentally, common marmosets, cotton-top tamarins and rhesus macaques are susceptible to Norwalk (the prototype norovirus) infection shedding virus after infection, although they did not exhibit clinical symptoms [49]. The limitations of using non-human primates for norovirus research mirror those detailed above for humans and, as such, very little published research data is available. Of promising note a newly discovered calicivirus, Tulane virus, found in rhesus macaques has been preliminarily characterised [50; 51]. This virus causes an as yet uncharacterised disease in its host and appears closely related to noroviruses, although it may represent a separate genus [50]. The relevance of this virus as a model for human norovirus disease seems high and it may provide a useful future model for the study of norovirus pathogenesis.

Non-norovirus human caliciviruses - Sapoviruses – These viruses are genetically similar to human noroviruses and cause an almost indistinguishable disease from their norovirus counterparts. They are also un-cultivatable in tissue culture and if anything complicate the diagnosis and research of human noroviruses. They are, as such, levy to the same benefits and limitations of the human noroviruses, in terms of their suitability as a model system.

Mice and murine norovirus – MNV has only recently been identified [52] and is quickly becoming the model of choice for human norovirus research. The virus is closely related to human noroviruses (genogroup V (GV) noroviruses – human viruses are found in GI, II and IV), replicates to high titres in tissue culture having a dendritic cell and macrophage tropism [37] and has a natural host which is both relatively cost-effective and genetically well-characterised. MNV is frequently used as a model of the immune response to norovirus infection since immune-knockout mice are readily available [48]. This has allowed an unparalleled examination of the host responses required for norovirus pathogenesis, clearance and establishment of immunity [53; 54; 55]. Furthermore it has provided useful guidance for the future development of vaccines [56; 57]. It is important to highlight however that, as with any indirect animal model, there are limitations to the usefulness of MNV as a model for human noroviruses. Although new strains of MNV are being identified every day, work thus far would indicate that the disease MNV causes in its host is different to that of the human norovirus. Mice do not routinely develop diarrhoea and cannot vomit. The murine disease is often described as persistent, while human noroviruses are characterised by their acute rapid infection and subsequent clearance [58; 59], although recent data indicates longer shedding can occur [12]. Also, the genetic variability of MNV is less than that of human noroviruses (variability of human noroviruses is considered to be responsible for repeated infection and short-lasting immunity), a fact that may hinder its role as a model for vaccine development [60]. Another important factor is the relevance of the apparent immune-cell-tropism of MNV; the tropism for human noroviruses in vivo being somewhat unclear at this juncture [56]. Despite these caveats, MNV is clearly an intestinal pathogen spread via the faecal-oral route and similarly to human noroviruses [61], MNV infection also exacerbates the onset of inflammatory bowel disease [62].

Pigs and caliciviruses – The case for pigs and pig viruses as a model for human norovirus infection is complicated. Caliciviruses that infect pigs include both noroviruses that cause a sub-clinical infection in adult pigs, and sapoviruses e.g. Porcine enteric caliciviruses (PEC) where the virus infects all ages, causing diarrhoea only in younglings [63; 64]. In addition, gnotobiotic pigs can be infected with human noroviruses [65], so in reality there are three potential models available. PECs have been used a model for tissue culture derived attenuation of an enteric calicivirus [66] and human noroviruses were used in infection of gnotobiotic pigs to model antibody and cytokine responses [67]. The porcine noroviruses, although sub-clinical in pigs, may prove important in evolutionary modelling if these viruses represent a natural reservoir and may be involved in zoonotic transfer [64; 48].

Sheep, cattle and ovine/bovine noroviruses – The prototype bovine norovirus strain Newbury agent 2 was identified in diarrhoeic calves in 1984 [48]; although the bovine noroviruses are less closely related to human norovirus than their swine counterparts [68] they still represent an attractive in vivo model, given the overall similarity of the viruses and the potential for zoonotic transfer. Recently noroviruses were discovered in sheep, identifying ovine species as another susceptible group closely connected to humans [69].

Cats and feline calicivirus – Feline calicivirus (FCV) represents perhaps an inappropriate model for human noroviruses. This is specifically because the disease it causes is respiratory or systemic in some cases, unlike the gastro-intestinal disease typified by NV. Historically, because of the virus's good growth in vitro it has often been used as a surrogate model for human noroviruses in the development of virocides, diagnostics and environmental stability studies [examples: 70; 71; examples: 72]. In addition, FCV can be readily genetically manipulated [73] hence it has also been used as a model for calicivirus replication and translation described in more detail below.

Rabbits, hares and rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV)/ Rabbit calicivirus (RCV)/European brown hare syndrome virus (EBHSV) – RHDV and EBHSV caliciviruses of the Lagovirus genus cause often fatal diseases characterised by hepatitis and haemorrhages [74] and represent a significant problem for the rabbit industries in countries such as America and China [75]. The severity of disease presents a unique opportunity to study calicivirus virulence, however the suitability of the model is questionable given the differing disease symptoms (Table 2). RCV on the other hand in non-pathogenic and has yet to be fully characterised [76].

Model systems for the study of the norovirus replicative cycle

Due to the lack of a system to propagate human noroviruses in tissue culture, information on the virus life cycle has been largely inferred from studies on other animal caliciviruses, for which systems to propagate viruses are readily available (Table 2). The replicative cycle of human noroviruses, like other positive strand RNA viruses, can be divided into three stages:

Early events: Virus attachment to host cells, entry, and genome release. As detailed above, these early events are thought to be the major hurdle in the study of the Norovirus replicative cycle in vitro, but several studies have highlighted how HBGAs play an important role in the susceptibility to human norovirus infection [reviewed in 77], although whether additional molecules function as receptors remains to be determined. In addition, noroviruses can also bind to heparan sulphate [78] and sialyl Lewis C neoglycoprotein [79] although whether they simply act as attachment molecules or functional receptors has yet to be determined.

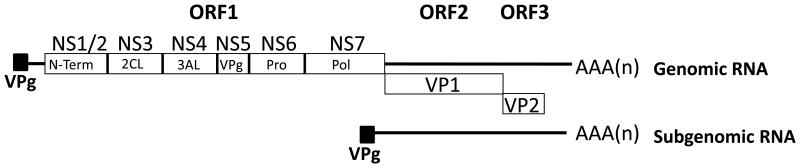

Viral biosynthetic events: Viral genome translation and replication. The calicivirus genome does not bear a 5′ cap structure commonly found on host cell mRNAs, but instead is covalently linked to a viral protein VPg [80; 18]. VPg is required for viral translation as it interacts with translation initiation factors to direct ribosome recruitment and protein synthesis [81; 82; 80; 83]. Translation of the human norovirus genome yields three open reading frames (Fig 2); ORF1 encodes a polyprotein which is then co- and post-translationally cleaved into various viral non-structural proteins responsible for replication, whereas ORF2 and 3 encode the major and minor capsid proteins respectively (Fig 2). Once translation has occurred, the RNA genome then serves as a template for the synthesis of new genomic and sub-genomic RNA (sgRNA) by the viral RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Due to the unavailability of a tissue culture system, our knowledge of the biosynthetic events which occur after the entry of human norovirus is severely limited.

Late events: virion assembly and release. Once genome replication has occurred, packaging of viral RNA takes place and results in the production of infectious virus particles. This stage of the virus life cycle has been the least studied.

Figure 2. Genome layout of the Norovirus genome.

The three open reading frames encoded by noroviruses are highlighted along with the names of the individual mature components. ORF1 components are depicted using the following abbreviations: N-Term, N-terminal protein, also known as NS1/2; 2CL, 2C-Like protein, also known as NS3; 3AL, 3A-Like protein, also known as NS4; VPg, viral protein-genome linked, also known as NS5; Pro, protease, also known as NS6; Pol, Polymerase, also known as NS7. The positions of the genomic and subgenomic RNAs are also highlighted.

Various model systems for the study of the norovirus replication cycle are discussed below, highlighting how they have been used to date and their suitability as a model for human noroviruses:

Tulane Virus –Studies with Tulane virus have demonstrated that an authentic 5′end of the viral RNA or the N-terminal protein is critical for infectivity and that the non-structural proteins are sufficient for genomic RNA replication and translation but structural proteins were essential for generation of progeny viruses [51].

Sapoviruses - Human sapoviruses have yet to be cultivated using in vitro cell culture, hence only studies with animal sapoviruses, namely porcine enteric calicivirus, have been performed. A reverse genetics system has been developed for PEC [84], wherein capped RNA transcripts derived from a cDNA clone were fully infectious. Successful propagation of PEC required the pre-incubation of cells with bile acids [85].

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) - RHDV is a highly virulent virus of rabbits (Table 1) and represents another system, for which an animal model, a tissue culture system and reverse genetics system is available [86]. Molecular studies have demonstrated that the minor capsid protein VP2 is not essential for virus infectivity [86] and that the 3′ poly A tail can be deleted with very little effect on virus replication in vitro [87]. Biochemical studies have also been undertaken using RHDV which have begun to unravel the mechanism of sgRNA synthesis, identifying a region of the viral genome which may act as a sgRNA promoter sequence [88]. Studies have also demonstrated that RHDV uses a novel mechanism of ribosome termination-reinitiation to drive expression of the minor capsid protein VP2 [89; 90].

Feline Calicivirus - Despite the obvious differences in the pathogenesis of FCV and human noroviruses, the early availability of reverse genetics system for FCV [73] made it an attractive model for the study of the molecular mechanism of calicivirus translation and genome replication. For example, it was shown that the components of the eIF4F complex (eIF4E, 4A, 4G) are required for efficient translation of FCV RNA [80]. It was also found that infection with FCV leads to an inhibition of cellular protein synthesis which appears to be associated with cleavage of the host translation initiation factors [91]. Studies with FCV also lead to the first identification of a functional protein receptor molecule for any calicivirus reported [92] and subsequent studies demonstrated that conformational changes in the viral capsid protein occur upon receptor binding [93]. FCV has also been used to identify the first functional host cell factor-viral genome interaction, highlighting that the RNA binding protein polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) is required for FCV replication [94]. Similar interactions have been observed for human norovirus but to date a functional role for these has yet to be demonstrated [95; 96; 97]

Murine norovirus - MNV has become the model of choice for many researchers in the field due to the high degree of genetic identity with human noroviruses (Fig 1 and Table 2), the readily available cell culture system, small animal model and recently developed reverse genetics systems [98; 99]. Two reverse genetics systems have been developed; one based on pol II driven expression of viral RNA [99] and the other based on T7 RNA polymerase driven expression of viral RNA [98]. In both cases, recovery of fully infectious virions was possible, although published data would indicate that the latter results in a greater yield of infectious virus (>10 fold higher). These systems have now been used to address some fundamental aspects of norovirus genome translation and replication. For example it was shown that cleavage of MNV protease-polymerase precursor form of the RdRp into separate units is essential for replication [99]. More extensive use of the T7 driven system has been published; it was shown that the correct sequence of the last nucleotide of the MNV genome, immediately upstream of the polyA tail is essential for recovery of infectious virus [98], a single amino acid substitution in the VP1 protein of MNV1 was sufficient to attenuate the virus in the STAT−/− mouse model [54] and the importance of RNA secondary structures present in the MNV genome for virus replication has been demonstrated [100]. Additional studies have characterised the binding of VPg to translation initiation factors in infected cells [80; 83], polyprotein processing [101] and the induction of apoptosis [102]. Recent studies have indicated that terminal sialic acid moieties on gangliosides function as an attachment receptor for MNV on murine macrophages [103].

Reverse genetics is another tool used for studying the molecular biology of viruses, including caliciviruses, as it allows the opportunity to examine the effect of genetic changes on the phenotype and virulence of a virus. Several attempts have been made to develop such system for human norovirus with limited success. For example the intracellular expression of NV cDNA using modified Vaccinia virus in mammalian cells resulted in the replication of viral RNA, translation and packaging into virus particles [104]. Virus particles produced in this system were indistinguishable from those isolated from stool samples but could not be cultivated due to the lack of a permissive cell line. As detailed above, transfection of cells with NV RNA isolated from stool samples has demonstrated that the major block to the in vitro cultivation of human noroviruses is at the level of virus entry [18]. A number of reverse genetics systems are available for other members of the Caliciviridae (Table 1); FCV [73], RHDV [86], PEC [84], MNV [98; 99], and very recently TV [51].

Choosing a suitable model

Choosing any relevant in vivo model for human norovirus experimentation depends greatly on the desired objective. The use of porcine and bovine norovirus models is attractive because these viruses are closely related to their human counterparts and may play an important role in human norovirus epidemiology and also potential zoonotic transfer; however, the work is obviously difficult and expensive. The murine norovirus system is cost effective and more advanced molecular techniques are readily available as well as genetically characterised and adaptable/mutatable hosts. However, the disease is different and the viruses themselves seem to be genetically distinct and in fact less variable. The absence of efficient tissue-culture cultivation techniques for human noroviruses combined with the inherent difficulties working with a human model incurs means animal models will always be an attractive option for researchers. Perhaps, in the near future, the newly identified Tulane virus of rhesus macaques will prove to be a useful and accurate in vivo model.

Antivirals

Current treatment for norovirus infections usually consists of quarantining the infected individual to prevent further spread and treating the main symptoms, primarily using antiemetic medication and oral or, in severe cases, intravenous rehydration [105; 106]. The development of norovirus vaccines has been the focus of much research over the past decade and still attracts great attention in the scientific field. However, conventional vaccines for human noroviruses are hampered by the inherent variability of these viruses and the lack of long-lasting protective immunity. Virus like particles (VLPs) generated using recombinant capsid protein from human noroviruses have been used to generate an antibody response in human volunteers which appears to be mostly IgG1 and IgA (Th1 response) [9]. The use of transgenic foodstuffs as a delivery method for these VLPs has also been examined; most volunteers developing a specific IgA response [33]. Recently, the MNV model system has been used to identify the immune responses required for effective ‘vaccination’. By immunising with either VLPs or live-virus and then challenging with MNV, scientists identified that a broad range response, including CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and B cells, is required for protective immunity [56]. Any effective human norovirus vaccine will likely have to stimulate such a response, with the additional caveat that it be specific either for all human noroviruses or, at least, the prevalent strain; given the increased variation seen for this virus. This high degree of genetic diversity would however indicate that the development of antiviral therapeutics is also an attractive area of research. Small molecule inhibitors of norovirus infection would provide an additional level of containment in areas where close person to person contact cannot be avoided and would be of particular use in environments where quarantine is difficult or impractical to enforce e.g. cruise ships, military camps and hospitals. Although the logistsics of administering therapeutics for an infectious agent with a short incubation period are complex, one might envisage that “ring-fence” treatment of individuals would prevent further dissemination of the disease. Antivirals would also be of use in immunocompromised individuals as although norovirus infection in healthy individuals is usually self resolving, with symptoms lasting around 2-3 days, in immunocompromised individuals norovirus infections have been reported to last much longer [107]. To date, the identification of small molecules capable of inhibiting norovirus replication has been limited; however some areas have shown promise and are described in more detail below:

Anti-sense morpholino oligonucleotides. Anti-sense technology has been used for some time as a method for inhibiting virus replication in tissue culture, however the in vivo use of anti-sense oligonucleotides has largely been limited as a result of the poor stability of unmodified antisense oligonucleotides. The use of peptide-conjugated phosphoramiamidate morpholino oligomers (PPMO) has overcome many of these limitations as they are nuclease resistant and readily enter cells. They function by forming a stable duplex with the target RNA and unlike siRNA, do not lead to target degradation but instead inhibit gene expression via steric blockage of protein synthesis. PPMO's are an attractive anti-viral strategy due to their high specificity and the fact that they can be readily synthesised to any new viral variant which may arise. The in vivo efficacy of PPMO's has been demonstrated for a number of highly pathogenic RNA viruses including poliovirus, Coxsackievirus B3, dengue virus, West Nile virus, Venezuelan Equine encephalitis virus, respiratory syncytial virus, Ebola virus and influenza A virus [Reviewed in 108]. The clinical use of phophooramiamidate morphino oligomers (PMO), not conjugated to peptides, for the treatment of calicivirus infections has recently been reported, clearly demonstrating their potential for this family of viruses [109]. Data would also indicate that PPMOs targeting the norovirus genome can lead to substantial reduction in norovirus gene expression at least in tissue culture [27], although to date the clinical use of PPMOs targeting norovirus replication has yet to be demonstrated. Morpholino oligomer technology holds great potential for the inhibition of norovirus infection although further studies are required.

Nucleotide analogues. Nucleotide analogues are well known for their capacity to inhibit RNA virus replication due to their ability to be incorporated into newly synthesised viral RNA by the viral RNA dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp). The most widely used and most well characterised is arguably Ribavirin. Ribavirin is already widely used in combination with interferon for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infections but is known to have antiviral activity against many positive strand RNA viruses, at least in vitro [110]. Ribavirin is known to act as an RNA virus mutagen as it can be incorporated into newly synthesised viral RNA in place of adenine or guanine, but when used as a template by the viral RdRp, it can be copied into either UTP or CTP resulting in the introduction of mutations into the viral genome [111]. This type of “lethal mutagenesis” has the effect of pushing the viral quasispecies to extinction and is described in more detail in references [112]; [113]. To date however, the clinical use of ribavirin for the prevention or control of human norovirus infection has yet to be examined but in vitro analysis using the human norovirus replicon containing cell line would indicate that it does possess anti-norovirus activity [26]. Further studies on the identification and characterisation of nucleotide analogues with anti-norovirus activity are required.

Other approaches. In addition to PPMO/PMO and nucleotide analogues described above, there have been a number of other potential targets for anti-norovirus antivirals. The viral cysteine protease (NS6) encoded as part of a large polyprotein from ORF1 is a key enzyme involved in virus replication. Cleavage of the viral polyprotein results in the production of several non-structural proteins, including the viral RdRp, required for viral genome replication. Therefore inhibition of protease activity may provide an effective mechanism of inhibiting norovirus replication. To date however, no norovirus protease inhibitors have been identified but our understanding of the function and specificity of the protease has greatly increased by numerous studies e.g. [114; 115; 101; 116]. In addition to polyprotein processing, our recent work has highlighted that the unique mechanism noroviruses use for protein synthesis may also provide a potential target for antiviral intervention [80]. Norovirus protein synthesis is dependent on the binding of host cell translation initiation factors to a virus encoded protein covalently linked to the 5′ end of the viral RNA genome [82; 80]. These interacting host cell proteins include components of the eIF4F cap-binding complex, of which the RNA helicase eIF4A is a component. The small molecule hippuristanol, purified from the sea fan coral Issis hippuris, inhibits the RNA helicase activity of eIF4A and was found to have a dramatic effect on MNV translation in vitro [80]. Targeting host enzymes as an antiviral strategy has the advantage that the development of viral resistance is less likely to occur, however it may result in adverse side effects. In the case of eIF4A, which itself is an essential component of the host cell translation initiation machinery, low levels of hippuristanol, which demonstrated little or no detectable effect on host cell viability, resulted in significant decreases in virus titre in tissue culture. Although it is unlikely that hippuristanol would be a suitable antiviral for clinical use, this work at least provides proof of principal that the unique mechanism noroviruses use for protein synthesis may provide a suitable antiviral target. Other potential approaches include the use of single chain antibodies [117], small molecule inhibitors of HBGA binding [118] and interferons [26; 119].

Future perspectives

The future of norovirus research is extremely exciting and given the inertia generated over the past decade by the many researchers in the field, the development of an efficient infectious cell culture system for human noroviruses in the next five years is highly likely. The elegant work of the Estes laboratory [104; 18], has made great progress in our understanding of the “missing link” required for norovirus replication in tissue culture. Hence, for the first time, those in the field now have the information required to identify ways to discover this factor or factors. Pioneering work from the Saif laboratory has increasingly highlighted the usefulness of pigs as a model system for norovirus pathogenesis [65; 63; 67] and although the discovery of murine norovirus has been a significant step in our understanding of norovirus translation and replication, the mouse animal model lacks many of the more attractive features required for the study of human norovirus virulence i.e. the ability to induce diarrhoea in an immunocompetent host. One might then predict that the combination of a fully infectious cell culture system, a reverse genetics system and the pig animal model for a human norovirus capable of inducing disease in pigs, would provide researchers with the ideal model system with which to dissect the molecular basis of norovirus virulence.

The identification of norovirus antivirals also holds much promise. Given the advances in the molecular techniques used to study noroviruses, we would predict that the next five years will lead to the identification of many strategies for controlling these important pathogens.

Executive Summary.

Norovirus cultivation in vitro

Noroviruses are a major cause of viral gastroenteritis in the developed world, yet we know little with regards to their molecular biology due to the unavailability of a tissue culture system.

Extensive studies have highlighted that the “missing-link” required for norovirus propagation in tissue culture is involved in early events i.e. virus entry and genome uncoating

Models for norovirus pathogenesis

Many animal caliciviruses are useful models for the study of human noroviruses; however none accurately reproduce all aspects of the disease in humans.

Model systems for the study of the norovirus replicative cycle

Many animal calicivirus can be cultivated in tissue culture, hence are good models for the study of genome translation and replication.

Murine norovirus probably represents the most authentic model system to date with which to study genome translation and replication.

Choosing a suitable model

A variety of animal models exist, however the model of choice largely depends on the research questions to be addressed.

Antivirals

Progress on the identification of anti-viral therapies for human noroviruses is limited; however the use of antisense technology and small molecule inhibitors holds much promise.

Acknowledgements

Work in the author's laboratory is funded by the Medical Research Council, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. IG is a Wellcome Senior Fellow. We would also like to apologise to the many authors whose work we have been unable to cite due to space restrictions

References

- 1.Kasper DL, B E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fankhauser RL, Noel JS, Monroe SS, Ando T, Glass RI. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(6):1571–8. doi: 10.1086/314525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallimore CI, Green J, Richards AF, Cotterill H, Curry A, Brown DW, et al. Methods for the detection and characterisation of noroviruses associated with outbreaks of gastroenteritis: outbreaks occurring in the north-west of England during two norovirus seasons. J Med Virol. 2004;73(2):280–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svraka S, Duizer E, Vennema H, de Bruin E, van der Veer B, Dorresteijn B, et al. Etiological role of viruses in outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis in The Netherlands from 1994 through 2005. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(5):1389–94. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02305-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopman BA, Reacher MH, Van Duijnhoven Y, Hanon FX, Brown D, Koopmans M. Viral gastroenteritis outbreaks in Europe, 1995-2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(1):90–6. doi: 10.3201/eid0901.020184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopman BA, Brown DW, Koopmans M. Human caliciviruses in Europe. J Clin Virol. 2002;24(3):137–60. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turcios-Ruiz RM, Axelrod P, John K, Bullitt E, Donahue J, Robinson N, et al. Outbreak of necrotizing enterocolitis caused by norovirus in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2008;153(3):339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SY, Tsai CN, Lai MW, Chen CY, Lin KL, Lin TY, et al. Norovirus infection as a cause of diarrhea-associated benign infantile seizures. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(7):849–55. doi: 10.1086/597256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girard MP, Steele D, Chaignat CL, Kieny MP. A review of vaccine research and development: human enteric infections. Vaccine. 2006;24(15):2732–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapikian AZ, Wyatt RG, Dolin R, Thornhill TS, Kalica AR, Chanock RM. Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. J Virol. 1972;10(5):1075–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.10.5.1075-1081.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolin R, Blacklow NR, DuPont H, Formal S, Buscho RF, Kasel JA, et al. Transmission of acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis to volunteers by oral administration of stool filtrates. J Infect Dis. 1971;123(3):307–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Estes MK, Crawford SE, Neill FH, et al. Norwalk virus shedding after experimental human infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(10):1553–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.080117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtz JB, Lee TW, Pickering D. Astrovirus associated gastroenteritis in a children's ward. J Clin Pathol. 1977;30(10):948–52. doi: 10.1136/jcp.30.10.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richmond SJ, Caul EO, Dunn SM, Ashley CR, Clarke SK, Seymour NR. An outbreak of gastroenteritis in young children caused by adenoviruses. Lancet. 1979;1(8127):1178–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91853-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop DHL. Complete transcription by the transcriptase of VSV. Journal of Virology. 1971;7:486–490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.7.4.486-490.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolin R, Blacklow NR, DuPont H, Buscho RF, Wyatt RG, Kasel JA, et al. Biological properties of Norwalk agent of acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1972;140(2):578–83. doi: 10.3181/00379727-140-36508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duizer E, Schwab KJ, Neill FH, Atmar RL, Koopmans MPG, Estes MK. Laboratory efforts to cultivate noroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(1):79–87. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guix S, Asanaka M, Katayama K, Crawford SE, Neill FH, Atmar RL, et al. Norwalk virus RNA is infectious in mammalian cells. J Virol. 2007;81(22):12238–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01489-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straub TM, Bentrup K H z, Orosz-Coghlan P, Dohnalkova A, Mayer BK, Bartholomew RA, et al. In Vitro Cell Culture Infectivity Assay for Human Noroviruses. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(3):396–403. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.060549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nickerson CA, Goodwin TJ, Terlonge J, Ott CM, Buchanan KL, Uicker WC, et al. Three-dimensional tissue assemblies: novel models for the study of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2001;69(11):7106–20. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.7106-7120.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unsworth BR, Lelkes PI. Growing tissues in microgravity. Nat Med. 1998;4(8):901–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond TG, Hammond JM. Optimized suspension culture: the rotating-wall vessel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281(1):F12–25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murakami K, Ishii K, Ishihara Y, Yoshizaki S, Tanaka K, Gotoh Y, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles in three-dimensional cultures of the cell line carrying the genome-length dicistronic viral RNA of genotype 1b. Virology. 2006;351(2):381–92. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marionneau S, Ruvoen N, Le Moullac-Vaidye B, Clement M, Cailleau-Thomas A, Ruiz-Palacois G, et al. Norwalk virus binds to histo-blood group antigens present on gastroduodenal epithelial cells of secretor individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(7):1967–77. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang K-O, Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, King AD, Green KY. Stable expression of a Norwalk virus RNA replicon in a human hepatoma cell line. Virology. 2006;353(2):463–73. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang KO, George DW. Interferons and ribavirin effectively inhibit Norwalk virus replication in replicon-bearing cells. J Virol. 2007;81(22):12111–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00560-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bok K, Cavanaugh VJ, Matson DO, Gonzalez-Molleda L, Chang KO, Zintz C, et al. Inhibition of norovirus replication by morpholino oligomers targeting the 5′-end of the genome. Virology. 2008;380(2):328–37. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham DY, Estes MK. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J. Virol. 1992;66(11):6527–6532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6527-6532.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green KY, Kapikian AZ, Valdesuso J, Sosnovtsev S, Treanor JJ, Lew JF. Expression and self-assembly of recombinant capsid protein from the antigenically distinct Hawaii human calicivirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(7):1909–14. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1909-1914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taube S, Kurth A, Schreier E. Generation of recombinant norovirus-like particles (VLP) in the human endothelial kidney cell line 293T. Arch Virol. 2005;150(7):1425–31. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0517-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baric RS, Yount B, Lindesmith L, Harrington PR, Greene SR, Tseng FC, et al. Expression and self-assembly of norwalk virus capsid protein from venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicons. J Virol. 2002;76(6):3023–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.3023-3030.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Z, Elkin G, Maloney BJ, Beuhner N, Arntzen CJ, Thanavala Y, et al. Virus-like particle expression and assembly in plants: hepatitis B and Norwalk viruses. Vaccine. 2005;23(15):1851–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tacket CO, Mason HS, Losonsky G, Estes MK, Levine MM, Arntzen CJ. Human immune responses to a novel norwalk virus vaccine delivered in transgenic potatoes. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(1):302–5. doi: 10.1086/315653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrington PR, Lindesmith L, Yount B, Moe CL, Baric RS. Binding of Norwalk virus-like particles to ABH histo-blood group antigens is blocked by antisera from infected human volunteers or experimentally vaccinated mice. J Virol. 2002;76(23):12335–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12335-12343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrington PR, Vinje J, Moe CL, Baric RS. Norovirus capture with histo-blood group antigens reveals novel virus-ligand interactions. J Virol. 2004;78(6):3035–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3035-3045.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wobus CE, Thackray LB, Virgin H W t. Murine norovirus: a model system to study norovirus biology and pathogenesis. J Virol. 2006;80(11):5104–12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02346-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wobus CE, Karst SM, Thackray LB, Chang KO, Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, et al. Replication of Norovirus in cell culture reveals a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(12):e432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parwani AV, Flynn WT, Gadfield KL, Saif LJ. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus in a continuous cell line. Effect of medium supplementation with intestinal contents or enzymes. Arch Virol. 1991;120(1-2):115–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01310954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapikian AZ. Overview of viral gastroenteritis. Archives of Virology. Supplementum. 1996;12:7–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ball JM, Graham DY, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Guerrero RA, Estes MK. Recombinant Norwalk virus-like particles given orally to volunteers: phase I study. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(1):40–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindesmith L, Moe C, Lependu J, Frelinger JA, Treanor J, Baric RS. Cellular and humoral immunity following Snow Mountain virus challenge. J Virol. 2005;79(5):2900–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2900-2909.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rockx B, Baric RS, de Grijs I, Duizer E, Koopmans MP. Characterization of the homo- and heterotypic immune responses after natural norovirus infection. J Med Virol. 2005;77(3):439–46. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atmar RL, Estes MK. Diagnosis of noncultivatable gastroenteritis viruses, the human caliciviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(1):15–37. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.15-37.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katayama K, Shirato-Horikoshi H, Kojima S, Kageyama T, Oka T, Hoshino F, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of the complete genome of 18 Norwalk-like viruses. Virology. 2002;299(2):225–239. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bull RA, Tanaka MM, White PA. Norovirus recombination. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 12):3347–59. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, Cannon JL, Zheng DP, Vinje J, et al. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Troeger H, Loddenkemper C, Schneider T, Schreier E, Epple HJ, Zeitz M, et al. Structural And Functional Changes Of The Duodenum In Human Norovirus Infection. Gut. 2008 doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.160150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scipioni A, Mauroy A, Vinje J, Thiry E. Animal noroviruses. Vet J. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rockx BH, Bogers WM, Heeney JL, van Amerongen G, Koopmans MP. Experimental norovirus infections in non-human primates. Journal of Medical Virology. 2005;75(2):313–20. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farkas T, Sestak K, Wei C, Jiang X. Characterization of a rhesus monkey calicivirus representing a new genus of Caliciviridae. Journal of Virology. 2008;82(11):5408–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00070-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei C, Farkas T, Sestak K, Jiang X. Recovery of infectious virus by transfection of in vitro-generated RNA from tulane calicivirus cDNA. Journal of Virology. 2008;82(22):11429–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00696-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karst SM, Wobus CE, Lay M, Davidson J, Virgin H W t. STAT1-dependent innate immunity to a Norwalk-like virus. Science. 2003;299(5612):1575–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1077905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mumphrey SM, Changotra H, Moore TN, Heimann-Nichols ER, Wobus CE, Reilly MJ, et al. Murine norovirus 1 infection is associated with histopathological changes in immunocompetent hosts, but clinical disease is prevented by STAT1-dependent interferon responses. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3251–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02096-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bailey D, Thackray LB, Goodfellow IG. A single amino acid substitution in the murine norovirus capsid protein is sufficient for attenuation in vivo. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7725–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00237-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCartney SA, Thackray LB, Gitlin L, Gilfillan S, Virgin HW, Colonna M. MDA-5 recognition of a murine norovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(7):e1000108. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chachu KA, LoBue AD, Strong DW, Baric RS, Virgin HW. Immune mechanisms responsible for vaccination against and clearance of mucosal and lymphatic norovirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(12):e1000236. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LoBue AD, Thompson JM, Lindesmith L, Johnston RE, Baric RS. Alphavirus-adjuvanted norovirus-like particle vaccines: heterologous, humoral, and mucosal immune responses protect against murine norovirus challenge. J Virol. 2009;83(7):3212–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01650-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu CC, Riley LK, Wills HM, Livingston RS. Persistent infection with and serologic cross-reactivity of three novel murine noroviruses. Comp Med. 2006;56(4):247–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsu CC, Riley LK, Livingston RS. Molecular characterization of three novel murine noroviruses. Virus Genes. 2007;34(2):147–55. doi: 10.1007/s11262-006-0060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thackray LB, Wobus CE, Chachu KA, Liu B, Alegre ER, Henderson KS, et al. Murine noroviruses comprising a single genogroup exhibit biological diversity despite limited sequence divergence. J Virol. 2007;81(19):10460–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00783-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khan RR, Lawson AD, Minnich LL, Martin K, Nasir A, Emmett MK, et al. Gastrointestinal norovirus infection associated with exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(3):328–33. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0b013e31818255cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lencioni KC, Seamons A, Treuting PM, Maggio-Price L, Brabb T. Murine norovirus: an intercurrent variable in a mouse model of bacteria-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Comp Med. 2008;58(6):522–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang QH, Souza M, Funk JA, Zhang W, Saif LJ. Prevalence of noroviruses and sapoviruses in swine of various ages determined by reverse transcription-PCR and microwell hybridization assays. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(6):2057–62. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02634-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang QH, Costantini V, Saif LJ. Porcine enteric caliciviruses: genetic and antigenic relatedness to human caliciviruses, diagnosis and epidemiology. Vaccine. 2007;25(30):5453–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheetham S, Souza M, Meulia T, Grimes S, Han MG, Saif LJ. Pathogenesis of a genogroup II human norovirus in gnotobiotic pigs. J Virol. 2006;80(21):10372–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00809-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo M, Hayes J, Cho KO, Parwani AV, Lucas LM, Saif LJ. Comparative pathogenesis of tissue culture-adapted and wild-type Cowden porcine enteric calicivirus (PEC) in gnotobiotic pigs and induction of diarrhea by intravenous inoculation of wild-type PEC. J Virol. 2001;75(19):9239–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9239-9251.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Souza M, Cheetham SM, Azevedo MS, Costantini V, Saif LJ. Cytokine and antibody responses in gnotobiotic pigs after infection with human norovirus genogroup II.4 (HS66 strain) Journal of Virology. 2007;81(17):9183–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00558-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliver SL, Dastjerdi AM, Wong S, El-Attar L, Gallimore C, Brown DW, et al. Molecular characterization of bovine enteric caliciviruses: a distinct third genogroup of noroviruses (Norwalk-like viruses) unlikely to be of risk to humans. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(4):2789–98. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2789-2798.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolf S, Williamson W, Hewitt J, Lin S, Rivera-Aban M, Ball A, et al. Molecular detection of norovirus in sheep and pigs in New Zealand farms. Vet Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bae J, Schwab KJ. Evaluation of murine norovirus, feline calicivirus, poliovirus, and MS2 as surrogates for human norovirus in a model of viral persistence in surface water and groundwater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(2):477–84. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02095-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buckow R, Isbarn S, Knorr D, Heinz V, Lehmacher A. Predictive model for inactivation of feline calicivirus, a norovirus surrogate, by heat and high hydrostatic pressure. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(4):1030–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01784-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Topping JR, Schnerr H, Haines J, Scott M, Carter MJ, Willcocks MM, et al. Temperature inactivation of Feline calicivirus vaccine strain FCV F-9 in comparison with human noroviruses using an RNA exposure assay and reverse transcribed quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction-A novel method for predicting virus infectivity. Journal of Virological Methods. 2009;156(1-2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sosnovtsev S, Green KY. RNA transcripts derived from a cloned full-length copy of the feline calicivirus genome do not require VPg for infectivity. Virology. 1995;210(2):383–90. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiel HJ, Konig M. Caliciviruses: an overview. Veterinary Microbiology. 1999;69(1-2):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McIntosh MT, Behan SC, Mohamed FM, Lu Z, Moran KE, Burrage TG, et al. A pandemic strain of calicivirus threatens rabbit industries in the Americas. Virol J. 2007;4:96. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Capucci L, Fusi P, Lavazza A, Pacciarini ML, Rossi C. Detection and preliminary characterization of a new rabbit calicivirus related to rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus but nonpathogenic. J Virol. 1996;70(12):8614–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8614-8623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Le Pendu J, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Kindberg E, Svensson L. Mendelian resistance to human norovirus infections. Semin Immunol. 2006;18(6):375–86. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tamura M, Natori K, Kobayashi M, Miyamura T, Takeda N. Genogroup II noroviruses efficiently bind to heparan sulfate proteoglycan associated with the cellular membrane. J Virol. 2004;78(8):3817–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.3817-3826.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rydell GE, Nilsson J, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Svensson L, Pendu J Le, et al. Human noroviruses recognize sialyl Lewis x neoglycoprotein. Glycobiology. 2009;19(3):309–20. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chaudhry Y, Nayak A, Bordeleau M-E, Tanaka J, Pelletier J, Belsham GJ, et al. Caliciviruses differ in their functional requirements for eIF4F components. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25315–25325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Daughenbaugh KF, Fraser CS, Hershey JW, Hardy ME. The genome-linked protein VPg of the Norwalk virus binds eIF3, suggesting its role in translation initiation complex recruitment. Embo J. 2003;22(11):2852–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goodfellow I, Chaudhry Y, Gioldasi I, Gerondopoulos A, Natoni A, Labrie L, et al. Calicivirus translation initiation requires an interaction between VPg and eIF4E. EMBO Reports. 2005;6(10):968–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Daughenbaugh KF, Wobus CE, Hardy ME. VPg of murine norovirus binds translation initiation factors in infected cells. Virol J. 2006;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang K-O, Sosnovtsev SS, Belliot G, Wang Q, Saif LJ, Green KY. Reverse Genetics System for Porcine Enteric Calicivirus, a Prototype Sapovirus in the Caliciviridae. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1409–1416. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1409-1416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang KO, Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Kim Y, Saif LJ, Green KY. Bile acids are essential for porcine enteric calicivirus replication in association with down-regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(23):8733–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401126101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu G, Ni Z, Yun T, Yu B, Chen L, Zhao W, et al. A DNA-launched reverse genetics system for rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus reveals that the VP2 protein is not essential for virus infectivity. J Gen Virol. 2008;89(Pt 12):3080–5. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/003525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu GQ, Ni Z, Yun T, Yu B, Zhu JM, Hua JG, et al. Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus poly(A) tail is not essential for the infectivity of the virus and can be restored in vivo. Arch Virol. 2008;153(5):939–44. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morales M, Barcena J, Ramirez MA, Boga JA, Parra F, Torres JM. Synthesis in vitro of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus subgenomic RNA by internal initiation on (−)sense genomic RNA: mapping of a subgenomic promoter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17013–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meyers G. Translation of the minor capsid protein of a calicivirus is initiated by a novel termination-dependent reinitiation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(36):34051–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meyers G. Characterization of the Sequence Element Directing Translation Reinitiation in RNA of the Calicivirus Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus. J. Virol. 2007;81(18):9623–9632. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00771-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Willcocks MM, Carter MJ, Roberts LO. Cleavage of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4G and inhibition of host-cell protein synthesis during feline calicivirus infection. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(Pt 5):1125–30. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Makino A, Shimojima M, Miyazawa T, Kato K, Tohya Y, Akashi H. Junctional adhesion molecule 1 is a functional receptor for feline calicivirus. J Virol. 2006;80(9):4482–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4482-4490.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bhella D, Gatherer D, Chaudhry Y, Pink R, Goodfellow IG. Structural insights into calicivirus attachment and uncoating. J Virol. 2008;82(16):8051–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00550-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Karakasiliotis I, Chaudhry Y, Roberts LO, Goodfellow IG. Feline calicivirus replication: requirement for polypyrimidine tract-binding protein is temperature dependent. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3339–3347. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gutierrez-Escolano AL, Brito ZU, del Angel RM, Jiang X. Interaction of cellular proteins with the 5′ end of Norwalk virus genomic RNA. J Virol. 2000;74(18):8558–62. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8558-8562.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gutierrez-Escolano AL, Vazquez-Ochoa M, Escobar-Herrera J, Hernandez-Acosta J. La, PTB, and PAB proteins bind to the 3(′) untranslated region of Norwalk virus genomic RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311(3):759–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sandoval-Jaime C, Gutiérrez-Escolano A. Cellular proteins mediate 5′-3′ end contacts of Norwalk virus genomic RNA. Virology. 2009;387(2):322. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chaudhry Y, Skinner MA, Goodfellow IG. Recovery of genetically defined murine norovirus in tissue culture by using a fowlpox virus expressing T7 RNA polymerase. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 8):2091–100. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82940-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ward VK, McCormick CJ, Clarke IN, Salim O, Wobus CE, Thackray LB, et al. Recovery of infectious murine norovirus using pol II-driven expression of full-length cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(26):11050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700336104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Simmonds P, Karakasiliotis I, Bailey D, Chaudhry Y, Evans DJ, Goodfellow IG. Bioinformatic and functional analysis of RNA secondary structure elements among different genera of human and animal caliciviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(8):2530–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Chang K-OK, Prikhodko VG, Thackray LB, Wobus CE, et al. Cleavage Map and Proteolytic Processing of the Murine Norovirus Nonstructural Polyprotein in Infected Cells. J Virol. 2006;80(16):7816–7831. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00532-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bok K, Prikhodko VG, Green KY, Sosnovtsev SV. Apoptosis in Murine Norovirus-Infected RAW264.7 Cells Is Associated with Downregulation of Survivin. J. Virol. 2009;83(8):3647–3656. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02028-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Taube S, Perry JW, Yetming K, Patel SP, Auble H, Shu L, et al. Ganglioside-linked terminal sialic acid moieties on murine macrophages function as attachment receptors for Murine Noroviruses (MNV) J. Virol. 2009;JVI:02245–08. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02245-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Asanaka M, Atmar RL, Ruvolo V, Crawford SE, Neill FH, Estes MK. Replication and packaging of Norwalk virus RNA in cultured mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(29):10327–10332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408529102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moe CL, Christmas WA, Echols LJ, Miller SE. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis associated with Norwalk-like viruses in campus settings. J Am Coll Health. 2001;50(2):57–66. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bucardo F, Nordgren J, Carlsson B, Paniagua M, Lindgren PE, Espinoza F, et al. Pediatric norovirus diarrhea in Nicaragua. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(8):2573–80. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00505-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gallimore CI, Lewis D, Taylor C, Cant A, Gennery A, Gray JJ. Chronic excretion of a norovirus in a child with cartilage hair hypoplasia (CHH) J Clin Virol. 2004;30(2):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stein DA. Inhibition of RNA virus infections with peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(25):2619–34. doi: 10.2174/138161208786071290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Smith AW, Iversen PL, O'Hanley PD, Skilling DE, Christensen JR, Weaver SS, et al. Virus-specific antiviral treatment for controlling severe and fatal outbreaks of feline calicivirus infection. Am J Vet Res. 2008;69(1):23–32. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.69.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Graci JD, Cameron CE. Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16(1):37–48. doi: 10.1002/rmv.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Crotty S, Maag D, Arnold JJ, Zhong W, Lau JY, Hong Z, et al. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an RNA virus mutagen. Nat Med. 2000;6(12):1375–9. doi: 10.1038/82191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Crotty S, Cameron C, Andino R. Ribavirin's antiviral mechanism of action: lethal mutagenesis? J Mol Med. 2002;80(2):86–95. doi: 10.1007/s00109-001-0308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Graci JD, Cameron CE. Therapeutically targeting RNA viruses via lethal mutagenesis. Future Virology. 2008;3(6):553–566. doi: 10.2217/17460794.3.6.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Belliot G, Sosnovtsev SV, Mitra T, Hammer C, Garfield M, Green KY. In vitro proteolytic processing of the MD145 norovirus ORF1 nonstructural polyprotein yields stable precursors and products similar to those detected in calicivirus-infected cells. J Virol. 2003;77(20):10957–74. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.10957-10974.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nakamura K, Someya Y, Kumasaka T, Ueno G, Yamamoto M, Sato T, et al. A norovirus protease structure provides insights into active and substrate binding site integrity. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13685–93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13685-13693.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scheffler U, Rudolph W, Gebhardt J, Rohayem J. Differential cleavage of the norovirus polyprotein precursor by two active forms of the viral protease. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 7):2013–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82797-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ettayebi K, Hardy ME. Recombinant norovirus-specific scFv inhibit virus-like particle binding to cellular ligands. Virol J. 2008;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Feng X, Jiang X. Library screen for inhibitors targeting norovirus binding to histo-blood group antigen receptors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(1):324–31. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00627-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Changotra H, Jia Y, Moore TN, Liu G, Kahan SM, Sosnovtsev SV, et al. Type I and type II interferons inhibit the translation of murine norovirus proteins. J Virol. 2009;83(11):5683–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00231-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]