Abstract

Study Objectives:

“Gentle handling” has become a method of choice for 4-6 h sleep deprivation in mice, with repeated brief handling applied before sleep deprivation to induce habituation. To verify whether mice do indeed habituate, we assess how 6 days of repeated brief handling impact on resting behavior, on stress, and on the subunit content of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) at hippocampal synapses, which is altered by sleep loss. We discuss whether repeated handling biases the outcome of subsequent sleep deprivation.

Design:

Adult C57BL/6J mice, maintained on a 12 h-12 h light-dark cycle, were left undisturbed for 3 days, then handled during 3 min daily for 6 days in the middle of the light phase. Mice were continuously monitored for their resting time. Serum corticosterone levels and synaptic NMDAR subunit composition were quantified.

Results:

Handling caused a ∼25% reduction of resting time throughout all handling days. After six, but not after one day of handling, mice had elevated serum corticosterone levels. Six-day handling augmented the presence of the NR2A subunit of NMDARs at hippocampal synapses.

Conclusion:

Repeated handling induces behavioral and neurochemical alterations that are absent in undisturbed animals. The persistently reduced resting time and the delayed increase in corticosterone levels indicate that mice do not habituate to handling over a 1-week period. Handling-induced modifications bias effects of gentle handling-induced sleep deprivation on sleep homeostasis, stress, glutamate receptor composition and signaling. A standardization of sleep deprivation procedures involving gentle handling will be important for unequivocally specifying how acute sleep loss affects brain function.

Citation:

Longordo F; Fan J; Steimer T; Kopp C; Lüthi A. Do mice habituate to “gentle handling?” A comparison of resting behavior, corticosterone levels and synaptic function in handled and undisturbed C57BL/6J mice. SLEEP 2011;34(5):679-681.

Keywords: Sleep deprivation, gentle handling, hippocampus, corticosterone, NMDA receptor

INTRODUCTION

The method of “gentle handling” to prevent sleep was initially used in cats and rats and involved tactile and acoustic stimuli and introducing novel objects into the cage.1,2 Gentle handling is now being used for total sleep deprivation in mice, involves touching the animals with the hand or a brush, shaking and tapping the cage, and is widely accepted as a way to keep mice awake for periods of hours, while minimally disturbing ongoing activity.3 However, their innate defensive behavior leads mice to escape from invasive and potentially dangerous stimuli. Thus, when confined to the laboratory cage, even mild stroking or cage shaking is perceived as a stressor and interferes with on-going behavior. Consistent with this possibility, sleep deprivation achieved by gentle handling in mice is typically associated with elevated corticosterone levels.3 Accordingly, direct manipulation of the animals is often minimized or avoided altogether.4–6

Alternatively, habituation strategies are adopted.7,8 These consist in repeatedly exposing mice to the handling manipulations for brief periods before sleep deprivation is carried out. Habituation of mice to an experimental apparatus or to a novel environment is important for proper performance in cognitive tasks,9 but whether mice adapt to handling in terms of sleep-wake behavior and stress response has been less explored. Routine laboratory procedures, such as animal lifting or moving the cage, cause significant stress to which mice adapt poorly.10 Moreover, animal husbandry conditions affect the acute response to experimental manipulation.11 Therefore, habituating mice to gentle handling raises questions related to the physiological constitution of mice and to the outcome of subsequent sleep deprivation. Do mice habituate to handling, and, if yes, on what time scale? Does handling impact positively on possible confounding factors of a subsequent acute sleep deprivation, such as stress reactions? Does handling modify other parameters known to be sensitive to sleep loss, therefore possibly attenuating or altering the outcome of acute sleep deprivation?

We studied the consequences of a short (3 min) handling procedure published recently, which involves a mixture of interventions on the mice for 6 days and, when combined with sleep deprivation, was found to modify the turnover of cAMP in hippocampal pyramidal cells.7 Parameters we chose for evaluation were resting behavior, stress, and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) subunit composition. The former two are critical for a well-controlled sleep deprivation, whereas the latter has been shown previously to be affected by stress-free acute SD.3,4,6,12 We find that handling before sleep deprivation affects these parameters in a manner that biases the outcome of sleep deprivation.

METHODS

For the monitoring of resting times, 9 adult C57BL/6J mice of either sex and maintained on a 12 h-12 h light-dark cycle (lights on from 06:00 to 18:00)5 were left undisturbed for 3 days and then handled daily for 6 days. Handling lasted for 3 min, started at 11:00 and involved cage shaking for 1 min, pursuing the animals with the hand in the cage and touching them for 1.5 min, and ∼65 dBA noise for 0.5 min by tapping at the cage. Resting time was continuously monitored by quantifying the distance moved/min using Ethovision 3.0 (Noldus), and means/h were calculated for the 3 undisturbed days, for the 6 handling days, and for the 1st and the last 2 handling days. The time from 11:00-11.15 was excluded from the analysis. Resting state was defined when the distance moved was, on average, < 0.25 cm/s, below which mice were judged as resting by visual observation.5 For corticosterone measurements and Western blots, 2 additional groups of mice were either left undisturbed or handled as described for 6 days. On day 7, animals were not disturbed and were sacrificed at 12:00. Serum corticosterone levels (n = 7) and synaptic NMDAR subunit composition (n = 6) were quantified.4 Two separate groups of 8 animals each were handled or left undisturbed for one day, and trunk blood was collected at 12:00 on the next day. The effect of handling on resting time was assessed using repeated-measures ANOVA with within-subject factor “Day,” followed by analysis of contrast variables for between-day comparisons. One-way ANOVA with factor “Treatment” was used for the corticosterone measurements, with Bonferroni multiple comparison test for post hoc analysis. The Student t-test was used to assess significance of the Western blot data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

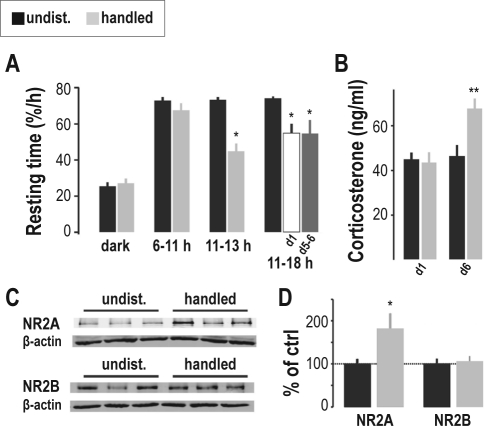

We began by assessing the impact of repeated handling on the spontaneous resting behavior of adult C57BL/6J mice (see Methods). Animals were first left undisturbed for 3 days, and subsequently handled for 6 days. Resting time during the dark phase was low and remained comparable for undisturbed and handling conditions (Figure 1A). Resting was also unaffected during the 5 h in the light that preceded handling (Figure 1A). In contrast, resting time was reduced in the period post-handling. In particular, while average resting time between 11:15-13:00 during the undisturbed baseline was 73.3% ± 1.4%/h (n = 9), it decreased to 44.8% ± 4.3%/h after handling (Figure 1A; n = 9; P < 0.05). The amount of resting time during that period was not different between day 1 and day 6 of handling (41.6% ± 4.7%/h vs. 36.6% ± 9.1%/h; P > 0.05). Decreased resting time was observed for up to 7 h after handling and persisted throughout days 5 and 6 (Figure 1A; 74.0% ± 1.2%/h for baseline, vs. 54.9% ± 5.2%/h for handling day 1, P < 0.01; 54.7% ± 7.4%/h for handling days 5-6, P < 0.05 vs. baseline; P > 0.05 vs. handling day 1), yielding a ∼ 25% reduction compared to baseline (Figure 1A). Repeated handling thus induced an immediate and persistent decrease in spontaneous resting time, indicating that mice did not habituate over a period of at least 6 days by regaining baseline resting time.

Figure 1.

Repetitive handling of mice leads to chronic reduction in hourly resting time, elevated stress hormone levels, and altered NMDAR subunit expression. (A) Resting time (%/h; mean ± SEM, n = 9), was calculated separately for the dark phase (dark), the light period prior to handling (6-11 h), and the light period after handling (11-13 h) and averaged across the 3 undisturbed (undist., dark bars) days and the 6 handling (handled, light gray bars) days. To test for habituation, resting was calculated for the post-handling light phase (11-18 h) for day 1 (d1, white bar) and days 5-6 (d5-6, dark gray bar) of repeated handling. *P < 0.05. (B) Corticosterone levels, determined 24 h after 1 (d1) and 6 days (d6) of handling (mean ± SEM, n = 8 for day 1, n = 7 for day 6). **P < 0.005. (C) Representative immunoblots for NR2A and NR2B and control β-actin levels are shown for 3 animals in each condition. (D) Normalized data from immunoblot analysis of purified synaptosomes (mean ± SEM, n = 6). *P < 0.05.

Next, we tested handling effects on stress, which represents a well-known confounding factor in sleep deprivation procedures.3,12 To monitor the time course of circulating corticosterone levels during the handling period, and to test for a possible habituation, trunk blood was collected 24 h after 1 (n = 8) or after 6 (n = 7) days of handling and plasma corticosterone compared to unhandled control mice. Mice handled for 6 days showed subtly, but significantly elevated corticosterone levels compared to undisturbed animals and to animals handled for one day only (Figure 1B; P < 0.005), which had comparable low levels typical for the time of day (P > 0.05).4 Corticosterone levels thus increase with a delay of at least one day following handling onset, strongly suggesting that factors associated with the repetition of handling are experienced as mild stress.

Finally, we assessed the subunit composition of hippocampal NMDARs, previously found to be sensitive to sleep loss.3 Western blots of purified hippocampal synaptosomal membranes,4 which report on synaptic membrane-bound protein content, were tested for the presence of the NR2A and the NR2B subunit, the former showing elevation in response to different forms of mild, stress-free sleep deprivation.5,6 Although variable from one animal to the next, after 6 days of repeated handling, the NR2A content was, on average, elevated to 182.2% ± 32.5% of control (Figure 1C, D; P < 0.05; n = 6), whereas NR2B protein content remained unaltered (Figure 1C, D; P > 0.05; n = 6). Consequences of handling are thus apparent at the level of NMDARs, suggesting that hippocampal function differs in handled compared to undisturbed animals.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate that handling can affect mice at the level of their spontaneous resting behavior, their humoral constitution, and their synaptic function. Mice invariably responded with disturbed resting behavior throughout all 6 days and showed a mild surge in circulating corticosterone levels. Handled mice are thus likely partially sleep restricted and show signs of stress. Moreover, handling provokes an alteration in the molecular make-up of NMDARs, suggesting modified hippocampal information processing. Altogether, repeated brief handling provokes a number of changes in mouse behavior and physiological constitution, which persist or even strengthen within 6 days, indicating a lack of habituation.

The delayed increase in corticosterone levels raises the possibility of a gradual sensitization of the stress axis by repeated handling, as described previously for acute-stress induced behavioral sensitization.13 Increased corticosterone release during the handling, a retardation of its decay or an elevated basal release could underlie this observation. Alternatively, mice may learn to anticipate the handling time and increase glucocorticoid levels in expectation of the next stressful experience. Sensitization could also result secondarily from disturbed sleep-wake behavior and/or altered synaptic function.

The molecular constitution of NMDARs is critical for bidirectional synaptic plasticity5 and for intracellular signalling.14 The augmentation of NR2A levels in response to repeated handling is a novel observation that further highlights the susceptibility of NMDAR subunit composition at adult hippocampal synapses to experience.3 The elevated corticosterone levels could possibly contribute to this experience-dependent form of NMDAR subunit trafficking, although it has been previously reported that much higher and more prolonged glucocorticoid elevations than those reported here affect NR2A and NR2B subunits of the hippocampal NMDAR to only a minor extent.15

Repeated disturbance of spontaneous resting behavior changes the reactivity of neuroendocrine and arousal systems to subsequent challenge, even when daily recovery is allowed.16 Together with the observations on corticosterone and NMDAR subunit composition, we thus conclude that prior handling of mice provokes a neurochemical state that preconditions mice to subsequent behavioral manipulation. Such bias could secondarily modify the outcome of a brief sleep deprivation. Specifically, the present data can provide an explanation for discrepant findings between sleep deprivation studies involving handled or naïve animals. For example, a recent study using handled mice did not detect sleep deprivation-induced changes in hippocampal NMDAR function,7 yet three studies not involving handling did.4–6 The handling-induced effects on NMDARs can occlude those observed by subsequent sleep deprivation, and also act on intracellular signalling cascades involved in hippocampal mnemonic functions, such as the cyclic nucleotide pathway.7,14

The detailed manipulations used to handle mice differ from one experimenter to the next, producing varying levels of resting time disturbance and stress.4,7,8,12 The present study, using a recently published brief handling procedure,7 thus highlights a potential risk that handled mice are preconditioned. Therefore, each repeated handling procedure would need to be tested separately for its potential impact and compared to sleep deprivation in unhandled mice. Moreover, stress susceptibility to enforced wakefulness varies with genetic background, implying that a bias introduced by handling may depend on mouse strain.12 It also remains to be investigated to what extent the comparatively invasive type of habituation used here could be attenuated by a gradually augmenting exposure to stimuli over periods larger than a week, and/or by combining handling with food reward.

Taken together, reconstructing the molecular and cellular links between sleep deprivation and brain function is likely to be modified by prior handling procedures. In documenting this point, our communication will contribute to the standardization of sleep deprivation procedures in mice, such that the consequences of these can be unambiguously attributed to acute sleep loss.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all lab members, and in particular Dr. S. Astori and R. Wimmer, for constructive input and critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. R. Kraftsik for help with statistical analysis. The authors acknowledge the helpful comments of Prof. Dr. P. Franken in the course of this study. The work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Nr. 3100A0-116006 and 3100A0-129810 to A.L.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Franken P, Dijk DJ, Tobler I, Borbély AA. Sleep deprivation in rats: effects on EEG power spectra, vigilance states, and cortical temperature. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R198–208. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ledoux L, Sastre JP, Buda C, Luppi PH, Jouvet M. Alterations in c-fos expression after different experimental procedures of sleep deprivation in the cat. Brain Res. 1996;735:108–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00599-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longordo F, Kopp C, Lüthi A. Consequences of sleep deprivation on neurotransmitter receptor expression and function. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1810–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopp C, Longordo F, Nicholson JR, Lüuthi A. Insufficient sleep reversibly alters bidirectional synaptic plasticity and NMDA receptor function. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12456–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2702-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longordo F, Kopp C, Mishina M, Lujáan R, Lüthi A. NR2A at CA1 synapses is obligatory for the susceptibility of hippocampal plasticity to sleep loss. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9026–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1215-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Pfister-Genskow M, Faraguna U, Tononi G. Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for net synaptic potentiation in wake and depression in sleep. Nature Neurosci. 2008;11:200–8. doi: 10.1038/nn2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vecsey CG, Baillie GS, Jaganath D, et al. Sleep deprivation impairs cAMP signalling in the hippocampus. Nature. 2009;461:1122–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modirrousta M, Mainville L, Jones BE. Orexin and MCH neurons express c-Fos differently after sleep deprivation vs. recovery and bear different adrenergic receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2807–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deacon RM. Housing, husbandry and handling of rodents for behavioral experiments. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:936–46. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balcombe JP, Barnard ND, Sandusky C. Laboratory routines cause animal stress. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2004;43:42–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijer MK, Sommer R, Spruijt BM, van Zutphen LF, Baumans V. Influence of environmental enrichment and handling on the acute stress response in individually housed mice. Lab Anim. 2007;41:161–73. doi: 10.1258/002367707780378168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mongrain V, Hernandez SA, Pradervand S, et al. Separating the contribution of glucocorticoids and wakefulness to the molecular and electrophysiological correlates of sleep homeostasis. Sleep. 2010;33:1147–57. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stam R, Bruijnzeel AW, Wiegant VM. Long-lasting stress sensitisation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:217–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajjhussein H, Suvarna NU, Gremillion C, Chandler LJ, O'Donnell JM. Changes in NMDA receptor-induced cyclic nucleotide synthesis regulate the age-dependent increase in PDE4A expression in primary cortical cultures. Brain Res. 2007;1149:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiland NG, Orchinik M, Tanapat P. Chronic corticosterone treatment induces parallel changes in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit messenger RNA levels and antagonist binding sites in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1997;78:653–62. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meerlo P, Sgoifo A, Suchecki D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]