Abstract

Pitx2, a paired-like homeodomain transcription factor, is expressed in post-mitotic neurons within highly restricted domains of the embryonic mouse brain. Previous reports identified critical roles for PITX2 in histogenesis of the hypothalamus and midbrain, but the cellular identities of PITX2-positive neurons in these regions were not fully explored. This study characterizes Pitx2 expression with respect to midbrain transcription factor and neurotransmitter phenotypes in mid-to-late mouse gestation. In the dorsal midbrain, we identified Pitx2-positive neurons in the stratum griseum intermedium (SGI) as GABAergic and observed a requirement for PITX2 in GABAergic differentiation. We also identified two Pitx2-positive neuronal populations in the ventral midbrain, the red nucleus and a ventromedial population, both of which contain glutamatergic precursors. Our data suggest that PITX2 is present in regionally restricted subpopulations of midbrain neurons and may have unique functions which promote GABAergic and glutamatergic differentiation.

Keywords: differentiation, transcription factor, nucleogenesis, superior colliculus, red nucleus

Introduction

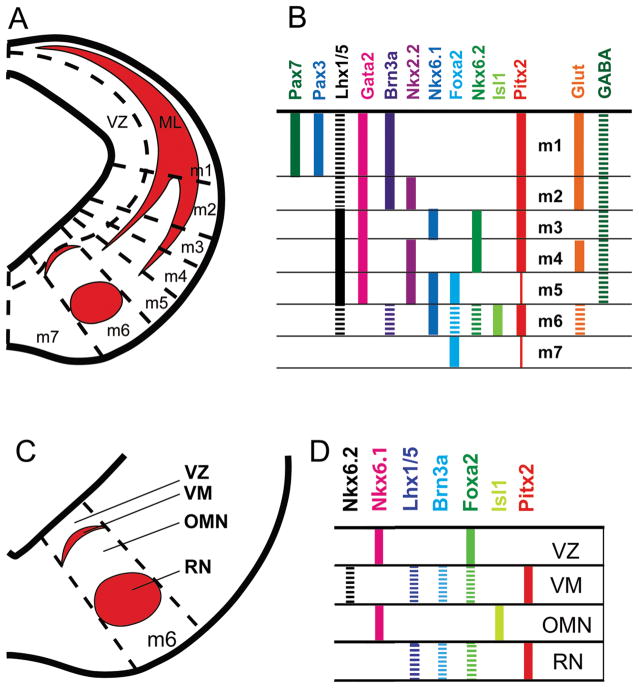

The midbrain is an important relay center that receives and processes sensory inputs and transmits signals to motor outputs in the hindbrain and spinal cord (Wickelgren, 1971; Meredith and Stein, 1986). The dorsal and ventral midbrain are divided by anatomic location and have distinct functional roles and developmental programs. The developing midbrain can be subdivided into three medio-lateral zones: a deeply localized ventricular zone, an intermediate zone, and a superficial mantle zone. Along the dorso-ventral axis, the midbrain is comprised of seven domains (m1–m7), each characterized by unique combinations of transcription factors, signaling molecules, and neurotransmitter expression (Nakatani et al., 2007; Kala et al., 2009). The dorsal domains (m1-m3) make up the superior colliculus and are organized into layers, whereas the ventral domains (m4–m7) are organized into distinct nuclei.

The superior colliculus receives multisensory inputs from the retina, cortex, and spinothalamic pathway (Mehler et al., 1960; Garey et al., 1968; Valverde, 1973). These inputs are important for movement of the head and limbs in response to stimuli, attention, and mediating saccades (Sparks and Mays, 1990; Kustov and Robinson, 1996; Lunenburger et al., 2001). Dorsal midbrain layers develop in an inside-out manner, whereby early born neurons migrate radially to reach a predestined layer, then migrate tangentially to their final rostro-caudal destinations (Edwards et al., 1986; Tan et al., 2002). In this fashion, older neurons occupy deeper layers and younger neurons are located more superficially (Altman and Bayer, 1981). Neurogenesis in the dorsal mouse midbrain occurs between E11.5–E14.5 (Edwards et al., 1986). Early born neurons migrate and differentiate such that by E18.5, all seven layers of the superior colliculus (stratum zonale (SZ), stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), stratum opticum (SO), stratum griseum intermedium (SGI), stratum album intermedium (SAI), stratum griseum profundum (SGP), and stratum album profundum (SAP)) are established (Altman and Bayer, 1981; Edwards et al., 1986). Between E18.5 and P6, collicular layers expand radially, become better defined, and undergo refinement of fiber bundles (Edwards et al., 1986).

The ventral midbrain is important for control of limb movement and locomotor coordination, and for mediating reward and stress responses (Le Moal and Simon, 1991; Feenstra et al., 1992; Sinkjaer et al., 1995). The ventral midbrain consists of domains m4–m7 and unlike the layered dorsal midbrain, is comprised of distinct nuclei (red nucleus, oculomotor nucleus, Edinger-Westphal nucleus, reticular formation, ventral tegmental area, and substantia nigra) that are organized in a stereotypic pattern (Hasan et al., 2010). During development, the ventral midbrain is divided into five morphogenetic arcs, each distinguishable by a unique pattern of transcription factor expression (Agarwala and Ragsdale, 2002; Sanders et al., 2002). Cells in these arcs are postulated to undergo nucleogenesis, during which cells receive specific signals to differentiate and migrate to form distinct anatomic nuclei based on their location within each arc (Agarwala and Ragsdale, 2002). Nucleogenesis in the ventral midbrain requires precise temporal and spatial control of transcription factor expression (Bayly et al., 2007; Andersson et al., 2008), although the unique contributions of these transcription factors have not been fully characterized.

Previous studies showed that the transcription factor PITX2 is required for proper midbrain development (Martin et al., 2004). Pitx2 is expressed in both dorsal and ventral midbrain subpopulations and is required for proper migration of collicular neurons into the intermediate zone and mantle zone (Martin et al., 2004). In the superior colliculus, a subpopulation of post-mitotic PITX2-positive neurons was identified as GABAergic (Martin et al., 2002). Ventral PITX2-positive populations have not been characterized. Other researchers have begun to map midbrain transcription factors by domain and factor co-expression (Nakatani et al., 2007; Kala et al., 2009), but PITX2 has not been incorporated into these maps. Here, we characterized dorsal and ventral midbrain Pitx2-positive cells for their neurotransmitter identities, localization within the neuroepithelium, and early co-expression with other transcription factors and signaling molecules. We also placed PITX2 within the emerging paradigm of m1-m7 dorso-ventral midbrain domains. Our results suggest that PITX2 may have unique roles in the development of midbrain GABAergic versus glutamatergic neurons.

Results

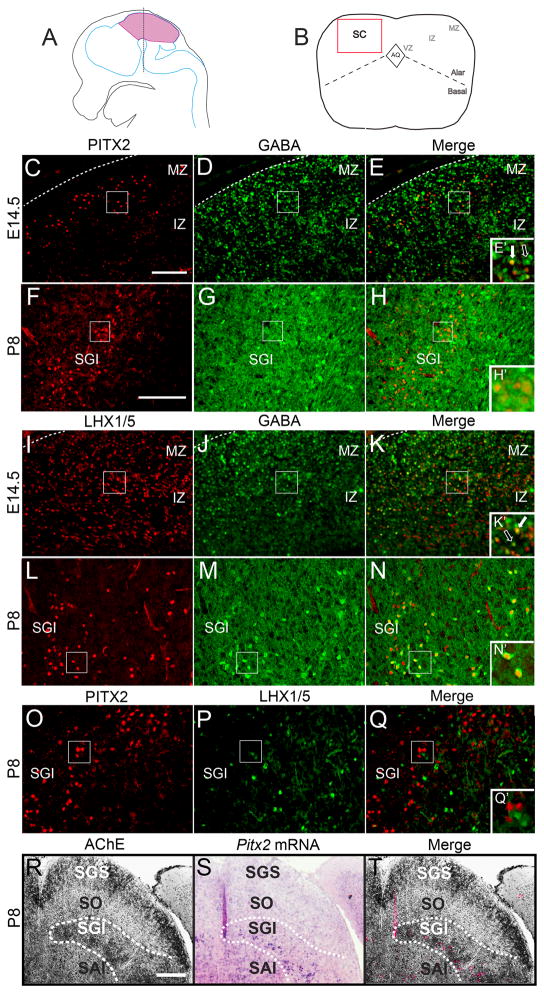

PITX2 is expressed in GABAergic neurons of the intermediate superior colliculus

To determine the identity of PITX2-positive neurons in the dorsal midbrain, we used double immunofluorescence with antibodies against PITX2 and markers of specific neurotransmitters. In the E14.5 superior colliculus, most PITX2-positive cells were positive for GABA (Fig. 1C–E′). At postnatal day 8 (P8), all PITX2-positive neurons in the superior colliculus had undergone GABAergic differentiation and were surrounded by GABAergic cytoplasm (Fig. 1F–H′). In order to determine whether GABAergic neurons could be identified by LHX1, a transcription factor expressed during collicular GABAergic differentiation (Kala et al., 2009), we analyzed collicular neurons for LHX1/5 and GABA co-localization. At E14.5, many intermediate collicular neurons were positive for both LHX1/5 and GABA (Fig. 1I–K′). Near the pial surface, the majority of GABA-positive neurons were LHX1/5-negative. At P8, densely labeled GABA-positive neurons continued to express LHX1/5 (Fig. 1L-N′). PITX2-positive cells were located superficial to LHX1/5 positive cells (Fig. 1O–Q′), indicating that PITX2 and LHX1/5 mark different GABAergic subpopulations of the superior colliculus.

Figure 1.

PITX2 identifies GABAergic interneurons in an intermediate layer of the dorsal midbrain. (A) Cartoon showing sagittal view of an embryonic mouse brain with midbrain highlighted in pink and a dotted line indicating the location of coronal sections shown in C–T. (B) Cartoon of a coronal midbrain section highlighting the superior colliculus (SC), aqueduct (AQ), alar-basal boundary, and the ventricular (VZ), intermediate (IZ), and mantle zones (MZ). (C–H) E14.5 and P8 midbrains processed for immunofluorescence for PITX2 (red) and GABA (green). Boxes in E and H are enlarged in E′ and H′. At E14.5, PITX2-positive and GABA-positive cells are located in the intermediate and mantle regions of the superior colliculus, where most PITX2-positive cells are also GABA-positive (E′). White arrow in E′ indicates co-localization of PITX2 and GABA. Open arrow indicates a GABA-positive, PITX2-negative neuron. (F–H′) At P8, PITX2-positive cells occupy an intermediate GABAergic layer of cells where GABA-positive cytoplasm surrounds PITX2-positive nuclei. (I–N′) E14.5 and P8 midbrains processed for immunofluorescence for LHX1/5 and GABA. Boxes in K and N are enlarged in K′ and N′. At E14.5, LHX1/5-positive cells are distributed throughout the superior colliculus, whereas GABA-positive cells reside in the intermediate and mantle zones. At P8, some LHX1/5-positive cells are GABA-positive (white arrow in K′). The open arrow in K′ indicates a GABA-positive, LHX1/5-negative neuron. (O–Q′) At P8, PITX2-positive neurons are localized superficial to the LHX1/5-positive population. (R–T) Adjacent sections from P8 brains processed for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) staining and Pitx2 in situ hybridization shows Pitx2 mRNA and AChE strongly expressed in an intermediate superior colliculus layer, the stratum griseum intermedium (SGI). Dotted lines indicate the outline of the AChE-positive layer. Scale bar in C is 100 μm and applies to panels C–E and I–K. Scale bar in F is 100 μm and applies to panels F–H and L–Q. Scale bar in R is 250 μm and applies to panels R–T. Figures in L–N′ were imaged using confocal microscopy. Abbreviations: mantle zone (MZ); intermediate zone (IZ); stratum griseum superficiale (SGS); stratum opticum (SO); stratum griseum intermedium (SGI); stratum album intermedium (SAI).

GABAergic neurons are abundant in the midbrain and are especially prevalent in the superficial layers and the intermediate layer (SGI) of the colliculus (Lee et al., 2007). The SGI receives numerous cholinergic inputs and can be identified by staining for the cholinergic enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) (McHaffie et al., 1991). To determine whether collicular PITX2-positive cells are located in the SGI, we analyzed dorsal midbrains for Pitx2 and AChE expression. At P8, the SGS and SGI were easily identified by strong AChE staining (Fig. 1R) and Pitx2-expressing cells were identified within the intermediate AChE positive layer (Fig. 1S, T), indicating that collicular Pitx2-positive neurons are located in the SGI.

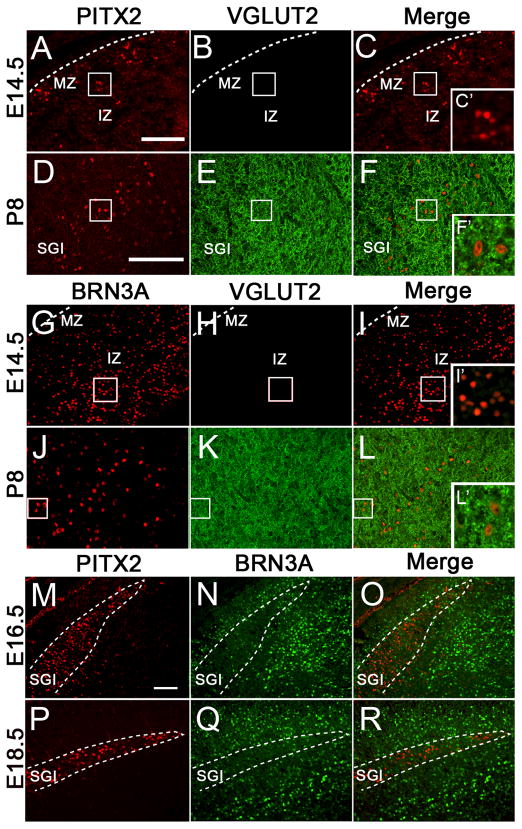

Because the SGI layer is rich in glutamatergic afferents, we analyzed the expression of PITX2 and vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2), a membrane transport protein responsible for glutamate uptake into vesicles. At E14.5, VGLUT2 was absent in the dorsal midbrain (Fig. 2A–C′). At P8, VGLUT2 was present throughout the intermediate and deep layers of the superior colliculus and was not co-localized at the cellular level with PITX2 (Fig. 2D–F′). This is consistent with known glutamatergic afferents projecting to the SGI including cortico-collicular, retino-collicular, and colliculo-collicular pathways (Woo et al., 1985; Mize and Butler, 1996; Olivier et al., 2000). To further characterize glutamatergic neurons in the colliculus, we analyzed expression of the transcription factor BRN3A, which marks the nuclei of glutamatergic precursor neurons (Fedtsova and Turner, 1995; Nakatani et al., 2007). BRN3A-positive cells were distributed throughout the E14.5 intermediate and medial superior colliculus (Fig. 2G–I′). At P8, BRN3A-positive nuclei were tightly associated with VGLUT2-positive label throughout the colliculus (Fig. 2J–L′), suggesting these BRN3A-positive cells are glutamatergic. We also examined PITX2 and BRN3A expression at E16.5 and E18.5. At E16.5, the PITX2-positive cell layer was tightly situated between two BRN3A layers with minimal intermingling among the cells (Fig. 2M–O), suggesting that BRN3A-positive cells are situated in the SAI and a sublayer within the SGI or SO. At E18.5, the BRN3A and PITX2-positive layers were more defined and no intermingling among cells in these layers occurred (Fig. 2P–R). Thus, collicular layers can be identified by unique transcription factor patterns.

Figure 2.

Collicular glutamatergic neurons are BRN3A-positive and PITX2-negative. Coronal sections of E14.5 and P8 midbrains were processed for immunofluorescence for PITX2 and VGLUT2 (A–F). Boxes in C and F are enlarged in C′ and F′. Dotted lines indicate the midbrain pial surface. (A–C′) At E14.5, VGLUT2 is absent from the dorsal midbrain. (D–F′) At P8, PITX2-positive cells are located in the SGI and VGLUT2-positive neurons occupy the intermediate and deep layers of the superior colliculus; however, VGLUT2-positive staining does not circumscribe the PITX2-positive nuclei. (G–L′) Coronal sections of E14.5 and P8 midbrains processed for immunofluorescence for BRN3A and VGLUT2. Boxes in I and L are enlarged I′ and L′. At E14.5, BRN3A-positive cells are located in the deep and intermediate superior colliculus, and VGLUT2 is absent. (J–L′) At P8, VGLUT2 circumscribes collicular BRN3A-positive nuclei. (M–R) Coronal sections from E16.5 (M–O) and E18.5 (P–R) embryos labeled with antibodies against PITX2 and BRN3A show that PITX2 is present in an intermediate layer positioned between two BRN3A-positive layers. (P–R) At E18.5, PITX2 and BRN3A continue to be localized in separate tectal layers and the PITX2-positive layer appears more compact. Dotted lines indicate the outline of the PITX2-positive collicular layer. Scale bar in A is 100 μm and applies to panels A–C and G–1. Scale bar in D is 100 μm and applies to panels D–F and J–L. Scale bar in M is 100 μm and applies to panels M–R. Panels D–F′ and J–L′ were imaged using confocal microscopy. Abbreviations: mantle zone (MZ); intermediate zone (IZ); stratum griseum intermedium (SGI).

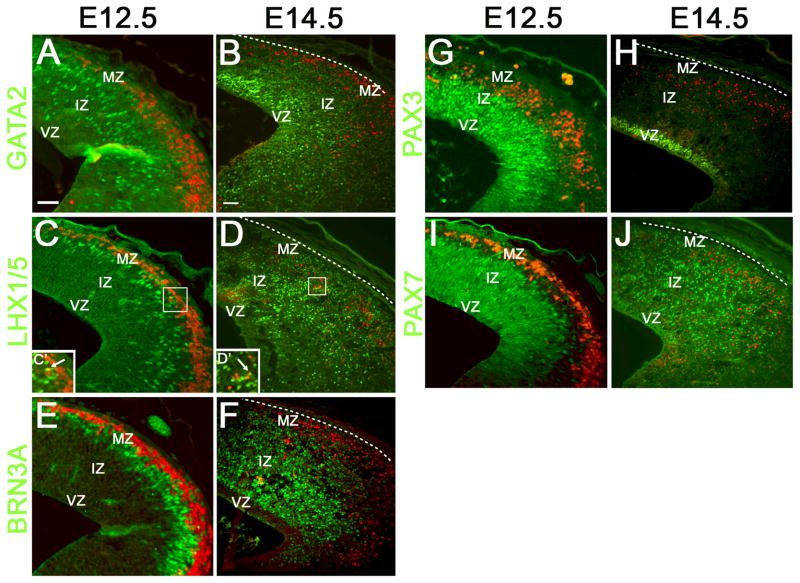

Collicular PITX2-positive GABAergic neurons have unique molecular signatures

Since Pitx2 is expressed in GABAergic neurons in the dorsal midbrain during early collicular differentiation, we reasoned it might be co-expressed with dorsal GABAergic precursor markers such as LHX1/5 and GATA2. GATA2 is a transcription factor expressed in post-mitotic neurons in the early stages of GABAergic differentiation and LHX1 is expressed downstream of GATA2 (Kala et al., 2009). At E12.5, GATA2-positive cells occupied the intermediate superior colliculus, whereas PITX2-positive neurons were found in the mantle zone (Fig. 3A). At E14.5, GATA2 was restricted to cells located superficial to the ventricular zone and did not co-localize with PITX2 (Fig. 3B). At E12.5, LHX1/5-positive cells were localized to the mantle zone, more superficially than GATA2, and found just deep to PITX2-positive neurons (Fig. 3C). At E14.5, LHX1/5-positive cells extended from the ventricular zone to the sub-pial surface (Fig. 3D). At both E12.5 and E14.5, only a few cells were positive for both PITX2 and LHX1/5 (Fig. 3C′, D′). Thus, PITX2, GATA2, and LHX1/5 appear to mark distinct subpopulations of GABAergic collicular neurons. At E12.5, BRN3A-positive cells were located adjacent and deep to PITX2-positive cells, whereas at E14.5 BRN3A was expressed throughout the ventral and intermediate colliculus (Fig. 3E, F). Collicular PITX2-positive cells are thus negative for BRN3A during early development, providing further evidence against glutamatergic identity of PITX2-positive cells.

Figure 3.

PITX2-positive cells represent a unique population of GABAergic dorsal midbrain precursors. Coronal sections of E12.5 and E14.5 midbrains were processed for double immunofluorescence with antibodies against markers of neuronal precursors. At E12.5 and E14.5, PITX2-positive cells (red) reside in the mantle layer of the superior colliculus. (A–B) GATA2-positive cells are located intermedially at E12.5 and extend throughout the superior colliculus at E14.5, but do not overlap with PITX2-positive cells. (C–D) LHX1/5 is located deep to PITX2 at E12.5 and by E14.5 LHX1/5-positive cells are found throughout the superior colliculus. At both timepoints, only a few neurons show co-localization of both markers (inserts in C′, D′). White arrows indicate cells with co-localization. (E–F) BRN3A and PITX2 are present in distinct cells at E12.5 and E14.5. (G–H) PAX3-positive cells are found throughout dorsal ventricular and intermediate zones and are PITX2-negative at E12.5. (H) At E14.5, PAX3-positive cells are PITX2-negative and ventricularly restricted. (I–J) PAX7-positive cells are broadly distributed throughout the superior colliculus and expanded superficially at E14.5 but do not co-localize with PITX2. Dotted lines indicate the pial surface. Scale bars in A and B are 100 μm and apply to panels A, C, E, G, I and B, D, F, H, J, respectively. Abbreviations: mantle zone (MZ); intermediate zone (IZ); ventricular zone (VZ).

Unlike GATA2, LHX1/5, and BRN3A, which are required for cell-type differentiation, PAX3 and PAX7 transcription factors are necessary for early superior colliculus establishment (Thompson et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2008). Pax3 is expressed transiently in all early collicular cells and expression disappears by birth (Thompson et al., 2008). Pax7 is also expressed in early collicular cells, but continues to be expressed in the mature colliculus where it regulates maintenance of superficial collicular layers (Thompson et al., 2008). We found no overlap between PITX2 and PAX3 or PAX7 at E12.5–E14.5 in the dorsal midbrain (Fig. 3G–J). Together, these data indicate that PITX2-positive neurons represent a subpopulation of superior colliculus cells with unique molecular signatures.

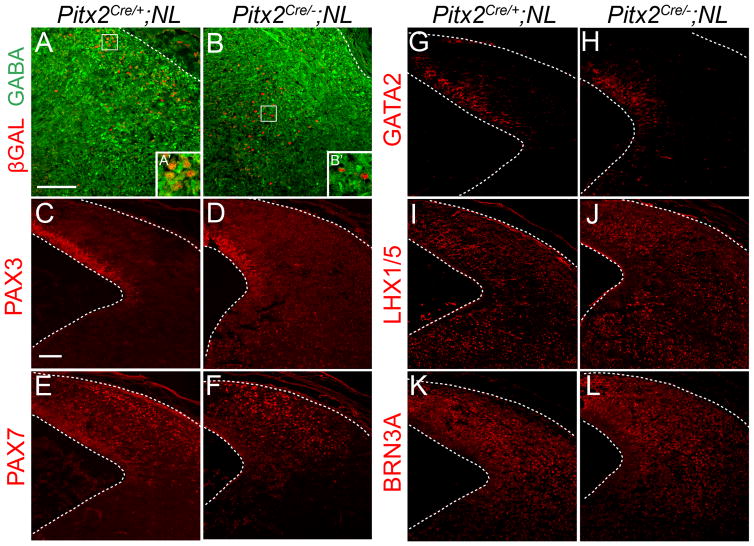

PITX2 is required for GABAergic differentiation, but not early collicular patterning

Previous studies showed that PITX2 is downstream of the transcription factor GATA2, which is necessary for collicular GABAergic differentiation (Kala et al., 2009). Additionally, in vitro studies suggested that mouse PITX2 activates the promoter of Gad1, which encodes the enzyme for GABA synthesis (Westmoreland et al., 2001). To determine whether PITX2 is required for collicular GABAergic differentiation, we crossed Pitx2Cre/+ mice to a nuclear LacZ (NL) reporter strain (Skidmore et al., 2008). Pitx2Cre/+;NL mice permanently express β-galactosidase (βGAL) in the nuclei of PITX2-lineage neurons (Skidmore et al., 2008). We compared E14.5 Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−;NL littermate midbrains for GABAergic differentiation of Pitx2-lineage cells. In Pitx2Cre/+;NL midbrains, βGAL-positive cells were positive for GABA and localized in the mantle zone in a highly GABAergic layer (Fig. 4A, A′). In Pitx2Cre/−;NL midbrains, βGAL-positive cells were medially mislocalized in a GABA-poor layer and were GABA-negative (Fig. 4B, B′). Interestingly, the Pitx2Cre/−;NL colliculus also appeared to have fewer βGAL-positive cells compared to Pitx2Cre/+;NL, suggesting there may be reduced neurogenesis or increased cell death of this population. These data suggest that PITX2 is required for both cellular migration and GABAergic differentiation in the superior colliculus.

Figure 4.

PITX2 is required for GABAergic differentiation. Coronal sections of E14.5 Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−;NL midbrains were processed for double immunofluorescence with antibodies against βGAL and GABA (A, B). Boxes in A and B are enlarged in A′ and B′. (A, A′) PITX2-lineage cells in the Pitx2Cre/+;NL embryo are located near the pial surface in a strongly GABAergic layer and are GABA-positive. (B, B′) PITX2-lineage cells in the Pitx2Cre/−;NL embryo are medially mislocalized and are GABA-negative. (C–L) Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−;NL coronal E14.5 midbrain sections were processed for immunofluorescence with antibodies against PAX3, PAX7, GATA2, LHX1/5, or BRN3A. (C–D) PAX3 is restricted to the ventricular zone in both Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−;NL embryos. (E–F) PAX7-positive cells are distributed throughout the colliculus of both Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−;NL midbrains. (G–H) GATA2 is restricted to deep collicular cells and loss of PITX2 does not affect GATA2 patterning. (I–L) In both Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−;NL midbrains, LHX1/5 and BRN3A-positive cells are spread throughout the superior colliculus. Panels A–L were imaged using confocal microscopy. Scale bars in A and C are 100 μm and apply to A–B and C–L, respectively.

To determine whether PITX2 is also necessary for early collicular patterning, we analyzed the expression patterns of early midbrain transcription factors in PITX2 mutant embryos. Loss of PITX2 did not disrupt the pattern of the general collicular precursor markers PAX3 and PAX7 (Fig. 4C–F, Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, the GABAergic precursor markers GATA2 and LHX1/5 and the glutamatergic precursor marker BRN3A were correctly localized in Pitx2Cre/−;NL midbrains (Fig. 4G–L). This indicates that although PITX2 is required for the GABAergic differentiation of a subpopulation of collicular neurons, it is not necessary for general early patterning of the superior colliculus.

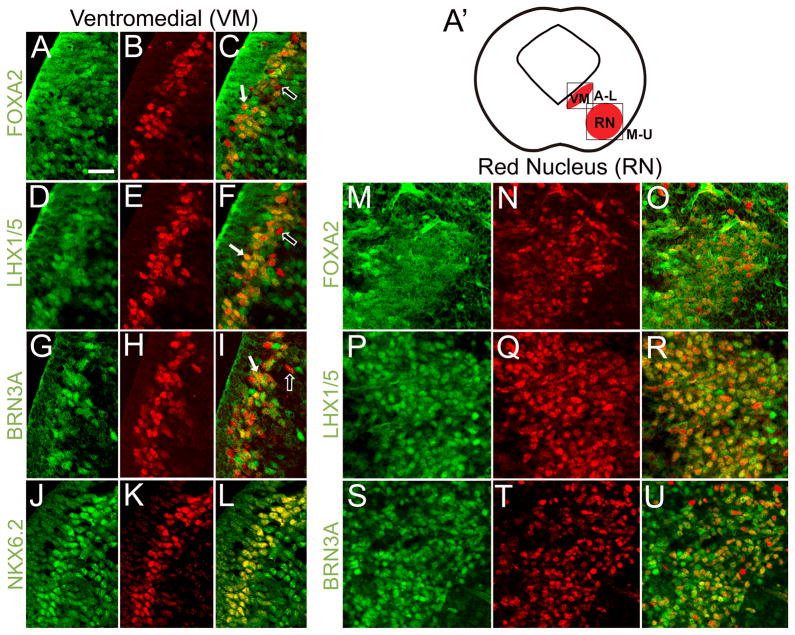

Ventral midbrain m6 domain PITX2-positive precursors have distinct ranscriptional profiles

To characterize the molecular profiles of m6 ventromedial and red nucleus PITX2-positive neurons, we analyzed early transcription factor co-localization with PITX2. At E12.5, many ventromedial PITX2-positive cells were also positive for FOXA2, LHX1/5, and BRN3A (Fig. 5A–I). In the m1–m5 domains, LHX1/5-positive neurons become GABAergic, whereas in the m6 domain, LHX1/5-positive cells become glutamatergic (Nakatani et al., 2007). Thus, PITX2 co-localization with LHX1/5 and BRN3A suggests a glutamatergic fate for many ventromedial m6 PITX2-positive cells. FOXA2 is present in the m6 and m7 domains, where it inhibits GABAergic differentiation via regulation of Nkx family transcription factors and repression of early factors necessary for GABAergic fates such as Helt (Ferri et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2009). Many ventromedial PITX2-positive cells were also positive for NKX6.2 (Fig. 5J–L), a transcription factor necessary for m6 identity (Prakash et al., 2009). Because all ventromedial PITX2-positive cells were also NKX6.2 positive, it is possible that ventromedial PITX2 marks a previously uncharacterized NKX6.2 subpopulation (Prakash et al., 2009). At E12.5, the majority of PITX2-positive red nucleus cells were also positive for FOXA2, LHX1/5, and BRN3A (Fig. 5M–U). These results suggest that PITX2 marks two heterogeneous cell populations in the ventral midbrain, a ventromedial one and a more lateral red nucleus population, both of which contain glutamatergic recursors that have distinct molecular signatures.

Figure 5.

PITX2 identifies restricted populations of ventromedial midbrain precursors. Immunofluorescence of E12.5 midbrain coronal sections processed with antibodies against PITX2 (red) and other ventral midbrain markers (green) and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A′) Cartoon showing coronal view of an embryonic mouse midbrain identifying two ventral PITX2-positive populations. Boxes indicate the location of the ventromedial (VM) and red nucleus PITX2-positive populations magnified in panels A–L and M–U, respectively. (A–C) FOXA2 marks precursors in the m6 domain and is co-localized with PITX2 in deep m6. (D–I) Most ventromedial PITX2-positive cells are positive for LHX1/5 and BRN3A, which mark glutamatergic precursors in the m6 domain. (J–L) NKX6.2-positive cells in deep m6 are also PITX2-positive. White arrows indicate transcription factor co-localization with PITX2, whereas open arrows indicate PITX2-positive, FOXA2, LHX1/5, or BRN3A-negative cells. Panels M–U focus on PITX2-positive cells in the red nucleus. (M–R) PITX2-positive cells in the red nucleus are FOXA2 and LHX1/5-positive. (S–U) Most but not all BRN3A-positive red nucleus cells are PITX2-positive. Scale bar in A applies to panels A–U and is 25 μm.

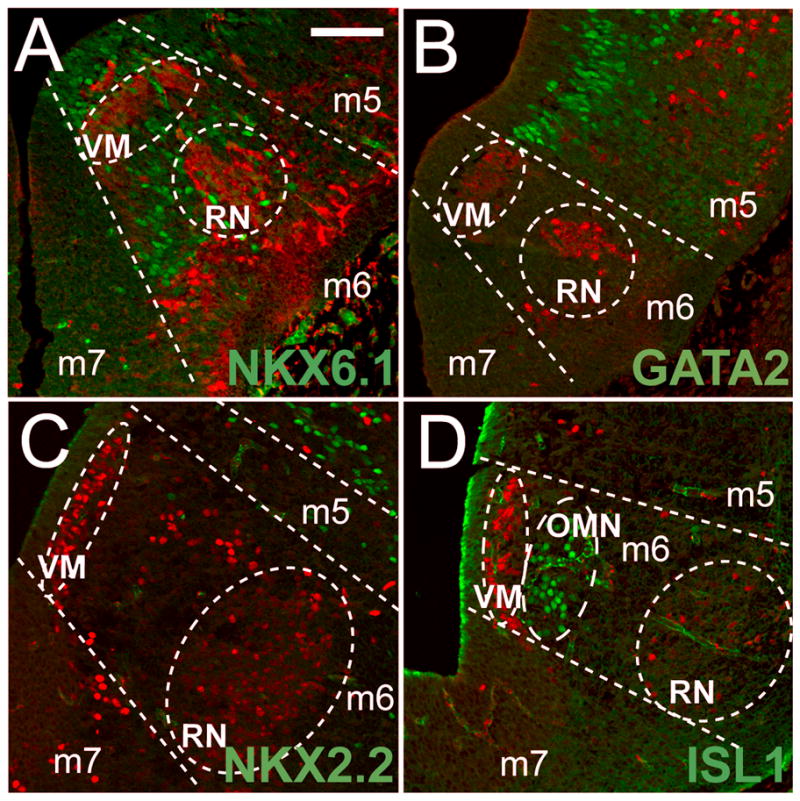

To further characterize Pitx2 expression in the ventral midbrain, we co-labeled PITX2-positive cells with additional ventral midbrain markers. In the ventral midbrain, Nkx2.2 is expressed in m5 progenitors and m4 post-mitotic cells (Nakatani et al., 2007), whereas NKX6.1 and NKX6.2 are expressed in m6. Nkx6.1 is expressed in m6 progenitors and in post-mitotic oculomotor neurons and is required for proper fate of cells in the red nucleus and oculomotor nucleus (Prakash et al., 2009). We found that NKX6.1-positive cells were located in the m6 ventricular zone and positioned between the two PITX2-positive populations, although no co-localization was observed between PITX2 and NKX6.1 (Fig. 6A). Nkx2.2 and Gata2 are expressed in m5 GABAergic progenitors and precursors, respectively (Nakatani et al., 2007; Joksimovic et al., 2009; Kala et al., 2009). Neither NKX2.2 nor GATA2 co-localized with PITX2 (Fig. 6B, C), further suggesting that ventral midbrain PITX2-positive neurons do not undergo GABAergic differentiation. ISLET1 (ISL1) marks the oculomotor nucleus in m6 and did not co-localize with PITX2, indicating that PITX2-positive cells do not contribute to the oculomotor nucleus (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Ventral midbrain domains are delineated by transcription factor patterning. E12.5 coronal sections were processed for immunofluorescence with antibodies against PITX2 (red) and other ventral midbrain markers (green) and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A) NKX6.1 is restricted to m6 progenitors and a PITX2-negative region between deep m6 and the PITX2-positive red nucleus. (B) Ventromedial PITX2-positive cells in m6 reside near GATA2-positive cells in the m5 domain. (C) NKX2.2-positive cells occupy m4 and m5, but not the m6 domain. (D) ISL1-positive oculomotor neurons (OMN) are located superficial to the deep PITX2 population in m6. Scale bar in A is 50 μm and applies to panels A–D. Abbreviations: ventromedial population (VM), red nucleus (RN), and oculomotor nucleus (OMN).

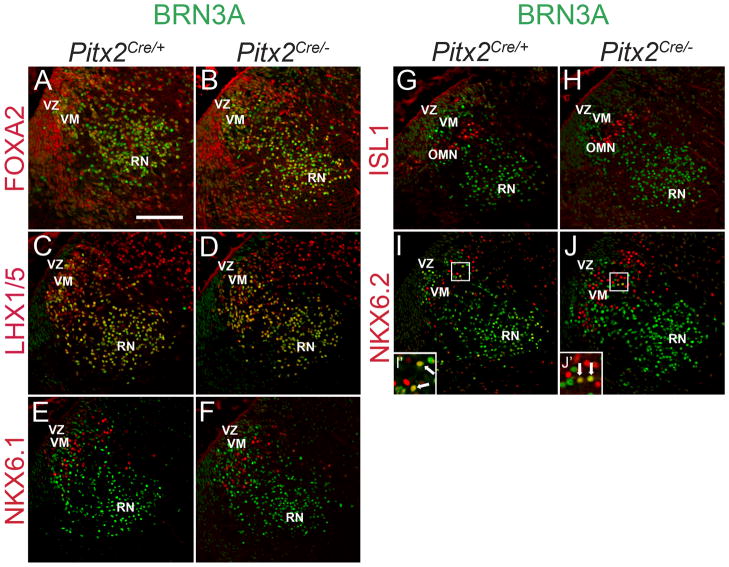

To determine whether PITX2 is necessary for early transcription factor patterning of the ventral midbrain, we compared gene expression in E12.5 Pitx2Cre/+ and Pitx2Cre/−littermate midbrains (Fig. 7). Transcription factor patterning in the midbrain was similar in Pitx2Cre/+ and wildtype embryos (Fig. 5). BRN3A (green) was dispersed throughout the ventromedial zone and red nucleus in both Pitx2Cre/+ and Pitx2Cre/− midbrains (Fig. 7A–J). FOXA2 was present in the ventricular zone, ventromedial population, and the red nucleus and was unchanged in Pitx2Cre/− embryos (Fig. 7A, B). LHX1/5-positive cells were distributed throughout the ventromedial population and the red nucleus in both Pitx2Cre/+ and Pitx2Cre/− midbrains (Fig. 7C, D). Loss of PITX2 did not affect the localization of NKX6.1 cells, which are BRN3A-negative (Fig. 7E, F). The oculomotor nucleus marker, ISL1, also appeared normal in Pitx2Cre/− midbrains (Fig. 7G, H). The majority of NKX6.2-positive cells were negative for BRN3A, with only a few double labeled cells in the intermediate zone of the ventral midbrain (Fig. 7I, I′); this pattern of expression was unchanged in Pitx2Cre/− embryos (Fig. 7J, J′). Transcription factor patterns also appeared unchanged in Pitx2Cre/− mutants in the rostral-caudal plane (Supplementary Fig. 1). Together, these data indicate that PITX2 is not necessary for early ventral midbrain patterning.

Figure 7.

Early ventral midbrain patterning is PITX2-independent. E12.5 coronal sections were processed for immunofluorescence with antibodies against BRN3A (green) and FOXA2, LHX1/5, NKX6.1, ISL1, or NKX6.2 (red) and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A–B) FOXA2-positive cells in m6 are localized in the ventricular zone and the BRN3A-positive red nucleus in both Pitx2Cre/+ and Pitx2Cre/− midbrains. (C–D) LHX1/5-positive cells are distributed from deep m6 to the red nucleus, where all LHX1/5-positive cells are also BRN3A-positive. LHX1/5 patterning appears unchanged in Pitx2Cre/− midbrains. (E–F) Cells in the ventricular zone are weakly NKX6.1-positive and a second, more lateral population is strongly NKX6.1-positive. Neither NKX6.1-positive population displays co-localization with BRN3A and both are unchanged in the Pitx2Cre/− midbrain. (G–H) In both Pitx2Cre/+ and Pitx2Cre/− tissues, ISL1 marks cells in the oculomotor nucleus which is surrounded by BRN3A-positive cells. (I–J′) NKX6.2-positive cells intermingle with BRN3A-positive cells and a few cells are also BRN3A-positive (white arrows) in both Pitx2Cre/+ and Pitx2Cre/− embryos. Scale bar in A is 100 μm and applies to panels A–J. Abbreviations: ventricular zone (VZ) ventromedial population (VM), and red nucleus (RN).

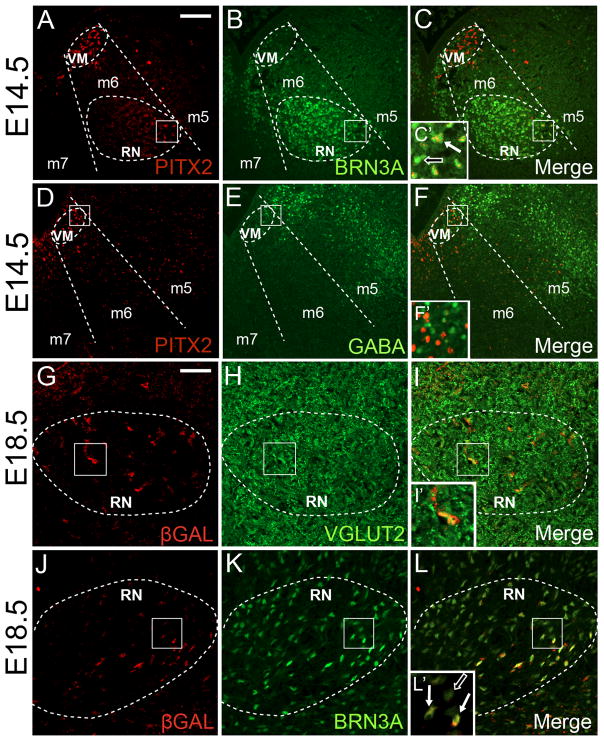

PITX2 is transient in glutamatergic red nucleus neurons

In order to establish whether ventral PITX2-positive neurons are GABAergic or glutamatergic, we analyzed E14.5 ventral midbrains for PITX2 and BRN3A, VGLUT2, or GABA. We found that only a few red nucleus cells were PITX2-positive at E14.5 (Fig. 8A), in contrast with the E12.5 PITX2-positive red nucleus (Fig. 5). At E14.5, the few ventral PITX2-positive cells were also BRN3A-positive, suggesting that these neurons become glutamatergic (Fig. 8B–C′). In contrast, most GABA immunofluorescence was localized to the m5 domain and was not present in PITX2-positive cells (Fig. 8D–′). Although previous studies suggested the presence of GABAergic neurons in the red nucleus (Katsumaru et al., 1984; Vuillon-Cacciuttolo et al., 1984), we did not observe GABA in midbrain red nucleus neurons during development (Fig. 8F).

Figure 8.

PITX2-lineage neurons are glutamatergic and sparse in the red nucleus. (A–F) Coronal sections of E14.5 midbrains processed for PITX2 and BRN3A (A–C) or GABA (D–F) immunofluorescence. Dotted areas demarcate cells in the PITX2-positive deep ventromedial population and the red nucleus. Boxes in C, F, I, and L are enlarged in C′, F′, I′, and L′. (A–C′) At E14.5, the red nucleus is composed of BRN3A-positive neurons, a few of which are PITX2-positive. White arrows indicate co-localization of BRN3A and PITX2, whereas open arrows indicate BRN3A-positive, PITX2-negative neurons. (D–F′) Ventral GABAergic neurons are generally restricted to the m5 domain, and are PITX2-negative. (G–L′) E18.5 Pitx2Cre/+;NL coronal sections were processed for immunofluorescence for β-galactosidase (βGAL) and VGLUT2 or BRN3A and visualized with confocal microscopy. (G–I′) At E18.5, PITX2-lineage neurons are present in the red nucleus and are VGLUT2-positive. (J–L′) E18.5 red nucleus PITX2-lineage neurons are also BRN3A-positive. White arrows indicate co-localization of βGAL and BRN3A, whereas the open arrow indicates BRN3A-positive, βGAL-negative neurons. Dotted areas delimit the boundary of the red nucleus. Scale bars in A and G are 100 μm and 50 μm and apply to panels A–F and G–L, respectively. Abbreviations: ventromedial population (VM) and red nucleus (RN).

We next asked whether PITX2-lineage red nucleus neurons are glutamatergic by analyzing Pitx2Cre/+;NL embryos for βGAL and VGLUT2 immunofluorescence. At E18.5, βGAL-positive red nucleus neurons were VGLUT2-positive, suggesting that red nucleus PITX2-lineage cells are glutamatergic (Fig. 8G–′). We also identified co-localization between βGAL and BRN3A in the red nucleus of Pitx2Cre/+;NL embryos (Fig. 8J–L). This co-localization with BRN3A further suggests that red nucleus PITX2-lineage neurons adopt a glutamatergic fate.

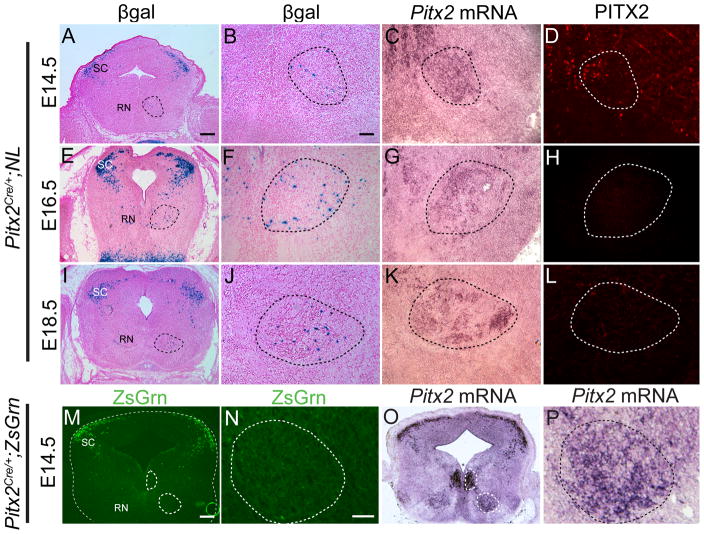

In the ventral midbrain, precise spatial and temporal transcription factor expression is critical for proper development (Sanders et al., 2002; Kele et al., 2006; Prakash and Wurst, 2006). Our studies on E12.5 and E14.5 ventral midbrains suggested that PITX2 may be downregulated in the red nucleus during development (Fig. 5M–, 8A–). To test this, we characterized midbrain Pitx2 expression at both the protein and mRNA levels using Cre lineage tracing, in situ hybridization, and immunofluorescence in Pitx2Cre/+;NL midbrains. From E14.5 through E18.5, PITX2-lineage βGAL-positive neurons were abundant in the superior colliculus and sparse in the red nucleus (Fig. 9A, E, I). Pitx2 mRNA expression was maintained in the superior colliculus, red nucleus, and ventromedial populations through E18.5 (Fig. 9C, G, K and data not shown). However, very few red nucleus neurons were labeled with PITX2 antibody at E14.5 and by E16.5 the red nucleus was devoid of PITX2-positive neurons (Fig. 9D, H, L).

Figure 9.

Pitx2 expression is transient in the ventral midbrain. (A–L) Adjacent coronal sections of Pitx2Cre/+;NL midbrains processed for βGAL histochemistry (A, B, E, F, I, J), Pitx2 mRNA (C, G, K) or PITX2 immunofluorescence (D, H, L). The dotted line demarcates the red nucleus. (A) At E14.5, Pitx2-lineage neurons are located in the superior colliculus (SC) and red nucleus (RN). (B) High magnification of panel A shows only a few Pitx2-lineage cells in the red nucleus, despite high red nucleus Pitx2 mRNA (C). (D) Immunofluorescence indicates only a few PITX2-positive red nucleus cells. (E, F, I, J) At E16.5–E18.5, β-galactosidase activity shows Pitx2-lineage neurons in the superior colliculus and red nucleus. (G, H, K, L) The E16.5–E18.5 red nucleus continues to express Pitx2 mRNA, although PITX2 protein is absent. (M) Coronal section of an E14.5 Pitx2Cre/+;ZsGrn midbrain showing ZsGrn fluorescence in the superior colliculus. Few cells are fluorescent in the ventral midbrain as seen in a high magnification image of the red nucleus (N). (O) A neighboring section to M processed for Pitx2 in situ hybridization shows Pitx2 mRNA in the superior colliculus, ventromedial population, and red nucleus. (P) Higher magnification of the red nucleus in O. Dotted areas denote the ventromedial population and red nucleus. Scale bar in A is 125 μm and applies to panels A, E, and I. Scale bar in B is 32μm and applies to panels B–D, F–H, and J–L. Scale bars in M and N are 100μm and 50 μm and apply to panels M, O and N, P, respectively.

Previous studies showed that Pitx2 mRNA is auto-regulated (Briata et al., 2003), which may partially explain the discrepancy in red nucleus Pitx2 mRNA and protein. It is also possible that translation or splicing of Pitx2 in this region is uniquely regulated in red nucleus neurons. Consistent with these data, some pituitary cell lines appear to regulate Pitx2 at the translational level (Tremblay et al., 1998). In order to determine whether the low number of βGAL-positive PITX2-lineage neurons in the red nucleus was due to low LacZ reporter expression, we also crossed Pitx2Cre/+ mice with ZsGreen mice, which express the green fluorescent molecule ZsGreen (ZsGrn) upon Cre recombination (Madisen et al., 2009). Midbrains of E14.5 Pitx2Cre/+;ZsGrn embryos displayed few ZsGrn-positive cells in the ventromedial population and red nucleus (Fig. 9M, N), even though neighboring sections showed significant Pitx2 mRNA expression in both populations (Fig. 9O, P). At E12.5, many PITX2-positive cells in the red nucleus can be identified by immunofluorescence (Fig. 5), whereas very few red nucleus neurons are βGAL-positive by lineage tracing in Pitx2Cre/+;NL embryos (data not shown). Since different Cre reporter systems (NL and ZsGrn) showed low Pitx2Cre activity in the E14.5 ventral midbrain, we speculate that Cre expression is regulated between E12.5 and E14.5 in the red nucleus at the transcriptional or translational level.

Discussion

Through use of co-expression studies and Cre lineage tracing, we have identified GABAergic PITX2-positive cells in the SGI, an intermediate layer of the superior colliculus, and in glutamatergic PITX2-positive cells in the ventral midbrain. Additionally, we characterized the expression of dorsal and ventral midbrain transcription factors in reference to temporal and spatial Pitx2 expression and determined a role for PITX2 in dorsal midbrain GABAergic differentiation. We also discovered that PITX2 protein is transient during development of the red nucleus.

Studies on the developing midbrain have begun to map transcription factor expression by dorso-ventral domain (Nakatani et al., 2007; Kala et al., 2009). Our data on Pitx2 expression in relation to other transcription factors can now be incorporated into these maps to produce a detailed summary of transcription factors during midbrain development (Fig. 10). We identified PITX2-positive cells in all seven midbrain domains, with strongest expression in the m1–m4 and m6 domains (Fig. 10A, B). In m1-m2 domains, Pitx2 is co-expressed with Lhx1/5 and GABA (Fig. 10B) and marks unique subpopulations of GABAergic neurons. This is consistent with previous studies showing distinct transcription factor requirements for Ascl1 and Gata2 in midbrain GABAergic differentiation (Peltopuro et al., 2010). The m6 midbrain PITX2-positive neurons can be divided into distinct regions: a ventromedial population and the red nucleus (Fig. 10C, D). In the m6 domain, Pitx2 is co-expressed with Lhx1/5, Brn3a, Foxa2, Nkx6.2, and Vglut2 (Fig. 10B, D). Interestingly, ventromedial and red nucleus PITX2-positive populations both express Foxa2, Lhx1/5, and Brn3a, whereas ventromedial PITX2-positive neurons also express Nkx6.2. This map suggests that Pitx2 marks distinctive midbrain subpopulations which have unique transcription factor expression patterns.

Figure 10.

Summary of Pitx2 expression in the developing dorsal and ventral midbrain. Schematic is based on previously published models (Nakatani et al., 2007; Kala et al., 2009), wherein early developmental transcription factors were mapped by domain. (A, C) Cartoons of typical E12.5 coronal sections showing PITX2-positive cells mapped onto the domain-delineated midbrain. PITX2-positive cells (red) are abundant in m1-m4 domains in the superior colliculus (SC) and in the m6 domain (C) containing a ventromedial (VM) population and the red nucleus (RN). PITX2-positive cells are sparse in m5 and m7. (B, D) Solid bars show areas with no overlap in marker expression with PITX2; hatched bars show areas of co-localization with PITX2. In m1–m4, PITX2-positive neurons express some markers of GABAergic precursors and neurons (LHX1/5 and GABA, respectively). In m6, PITX2 co-localizes with glutamatergic markers (D). PITX2 is co-localized with the m6 precursor markers FOXA2, LHX1/5, BRN3A, and NKX6.2 in the ventromedial population. PITX2 neurons in the early red nucleus are positive for FOXA2, LHX1/5, and BRN3A and red nucleus PITX2-lineage neurons are glutamatergic. Abbreviations: dopaminergic neurons (DA); glutamatergic neurons (GLUT); GABAergic neurons (GABA); ventricular zone (VZ); ventromedial population (VM); oculomotor nucleus (OMN); red nucleus (RN); mantle layer (ML).

Midbrain development requires distinct expression patterns of transcription factors and signaling molecules

Our studies suggest that superior colliculus layers in the mouse can be identified based on transcription factor expression. We also demonstrated that PITX2 marks the intermediate layer (SGI) of the superior colliculus and previous studies showed that superficial and intermediate layers can be identified by expression of Pax7 and Brn3a (Fedtsova et al., 2008). Our studies suggest BRN3A marks the SO/SGI and SAI, consistent with previous studies on collicular glutamatergic localization (Mooney et al., 1990). We showed that PITX2 and BRN3A-positive populations occupy separate layers. Additionally, previous studies showed that both the SGI and the SGP can be identified by expression of the Forkhead-5 (Foxb1) transcription factor (Alvarez-Bolado et al., 1999). Thus, developing superior colliculus layers can be identified by unique combinations of transcription factor expression.

We have also shown that Pitx2 is expressed upstream of and is necessary for GABAergic differentiation in PITX2-positive superior colliculus cells. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing PITX2 is downstream of the GABAergic differentiation factor GATA2 (Kala et al., 2009). This positions PITX2 late in a cascade of transcription factors necessary for GABAergic differentiation. The earliest fate-choice factors, Ascl1 and Helt, promote GABAergic differentiation (Miyoshi et al., 2004; Kala et al., 2009). In turn, Helt is necessary for the expression of Gata2, which is required for both Lhx1/5 and Pitx2 expression.

In the ventral midbrain, we identified Pitx2 expression in a ventromedial population and in the red nucleus. Ventral midbrain populations form arcs, each of which expresses a specific combination of transcription factors necessary for nucleogenesis. Arc formation requires Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling from the notochord and loss of Shh signaling results in disruption of arc structure and patterning (Bayly et al., 2007). Shh signaling contributes to the entire ventral midbrain and is required for repression of the dorsalization factors Pax7, En2, and Fgf8 (Nomura and Fujisawa, 2000; Watanabe and Nakamura, 2000). SHH is also responsible for inducing Foxa2 expression, which regulates Nkx family members and ventral midbrain specification (Perez-Balaguer et al., 2009). In addition to general ventral midbrain determination, studies in other tissues have shown that SHH indirectly regulates Pitx2 expression (Logan et al., 1998; Ryan et al., 1998), further suggesting a requirement for SHH signaling in PITX2-neuronal development.

Neurotransmitter identity is heterogeneous in PITX2 positive CNS neurons

We characterized dorsal PITX2-positive neurons as GABAergic, consistent with previous studies (Martin et al., 2004), and ventral PITX2-positive neurons as glutamatergic. Studies in the spinal cord have identified PITX2-positive neurons as cholinergic and glutamatergic interneurons that are responsible for modulating the frequency of motor neuron firing (Zagoraiou et al., 2009). Together, these observations suggest that PITX2 may regulate neurotransmitter choice based on rostral-caudal positioning. This reliance on regional or axial-level factors for midbrain development is consistent with earlier studies showing that dorsal and ventral midbrain neurons are derived from different progenitor pools (Tan et al., 2002) and respond to distinct developmental signals.

In conclusion, we report that Pitx2 is expressed in GABAergic neurons occupying the SGI and that PITX2 is necessary for their GABAergic differentiation and migration, but not early patterning. In contrast, most ventral Pitx2-lineage neurons are glutamatergic and are located in ventromedial and red nucleus populations. Additionally, each PITX2-positive population appears to be characterized by a unique combination of transcription factors, suggesting locally regulated mechanisms are important for glutamatergic and GABAergic differentiation. Further research into the developmental requirements of these neuronal subpopulations may facilitate diagnosis and insights into mechanisms of diseases/disorders and therapies for midbrain related neurological conditions.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Wild type mice were on a C57BL/6J background (JAX 000664). Pitx2Cre/+ mice (Liu et al., 2002) were crossed with FlpeR mice (JAX 003946) to excise the neomycin cassette. Pitx2Cre/+;NL and Pitx2Cre/−ryos were generated as previously described (Skidmore et al., 2008). ZsGrn reporter mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and are on a C57BL/6J background (JAX 007906) (Madisen et al., 2009).

Embryo Tissue Preparation for Cryosectioning or Paraffin Embedding

Timed pregnancies were established with the morning of plug identification designated as E0.5. Pregnant dams were euthanized using cervical dislocation. Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes-2 hours depending on age and genotype. Embryos for cryosectioning were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose-PBS overnight and frozenin O.C.T. embedding medium (Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA, USA), and sectioned at 12 μm. Paraffin embedded embryos were sectioned at a thickness of 7 μm. From each embryo and pup, an amniotic sac or tail was retained for genotyping. All procedures were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care for Animals at the University of Michigan.

β-galactosidase Staining of Frozen Sections

To collect embryonic tissue for X-Gal staining, Pitx2Cre/+ females were crossed with Pitx2+/+;NL males. Pregnant dams were anesthetized with 250 mg/kg body weight tribromoethanoland perfusion fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher, Waltham, MA). E14.5 whole embryos and E16.5–E18.5 brains were isolated and further fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 20 minutes to 3 hours. P8 pups were anesthetized as described above and perfusion fixed. Brains were removed and fixed at 4°C for 3 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were washed with PBS, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose-PBS overnight, and frozenin O.C.T. embedding medium (Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA, USA) for cryosectioning. Frozen sections were post-fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde fixative, washed in X-Gal Wash Buffer, and stained with X-Gal Staining Solution overnight at 37° as previously described (Sclafani et al., 2006). Slides were washed in PBS and X-Gal Wash Buffer, eosin counterstained and mounted with Permount (Fisher, Waltham, MA).

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Staining of Frozen Sections

To collect postnatal tissue for AChE staining, wild type P8 tissue was prepared and frozen as described above. Sections were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated in 0.1% H2O2. AChE staining was performed as previously described (Tago et al., 1986).

Immunofluorescence and In Situ Hybridization

Immunofluorescence on frozen and paraffin embedded tissue was performed as described (Martin et al., 2002; Martin et al., 2004) with rabbit anti-PITX2 at 1:8000 (Zagoraiou et al., 2009), rabbit anti-PITX2 at 1:4000 (Capra Science, Angelholm, Sweden), guinea pig anti-BRN3A at 1:400 (Fedtsova and Turner, 1995), rabbit-anti VGLUT2 at 1:1000 (Millipore), rabbit anti-GABA at 1:1000 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), guinea pig anti-GATA2 at 1:500 (Peng et al., 2007), guinea pig anti-NKX6.2 at 1:8000 (Vallstedt et al., 2001), chicken anti-β-galactosidase at 1:200 (Abcam) and the following mouse antibodies from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank: anti-LHX1/5 (4F2) at 1:100, anti-FOXA2 (4C7) at 1:100, anti-ISLET1 (40.2D6) at 1:500, anti-NKX2.2 (74.5A5) at 1:500, anti-PAX3 at 1:100, anti-PAX7 at 1:100, or anti-NKX6.1 (F64A6B4) at 1:250. In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Martin et al., 2002; Martin et al., 2004) using a cRNA probe for Pitx2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people for providing mice and reagents: T.M. Jessell for the polyclonal PITX2 and NKX6.2 antibodies, Eric Turner for the BRN3A antibody, and Kamal Sharma for the GATA2 antibody. The LHX1/5, FOXA2, EN1, ISLET1 and NKX2.2 antibodies were developed by T.M. Jessell, PAX3 antibody by C.P. Ordahl, PAX7 antibody by A. Kawakami, and NKX6.1 antibody by O.D. Madsen were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242. Some of these data were presented in abstract form at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, 2009. This work was supported by a Rackham Regents Fellowship to MRW and NIH R01 NS054784 to DMM.

References

- Agarwala S, Ragsdale CW. A role for midbrain arcs in nucleogenesis. Development. 2002;129:5779–5788. doi: 10.1242/dev.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Time of origin of neurons of the rat superior colliculus in relation to other components of the visual and visuomotor pathways. Exp Brain Res. 1981;42:424–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00237507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Bolado G, Cecconi F, Wehr R, Gruss P. The fork head transcription factor Fkh5/Mf3 is a developmental marker gene for superior colliculus layers and derivatives of the hindbrain somatic afferent zone. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;112:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson ER, Prakash N, Cajanek L, Minina E, Bryja V, Bryjova L, Yamaguchi TP, Hall AC, Wurst W, Arenas E. Wnt5a regulates ventral midbrain morphogenesis and the development of A9–A10 dopaminergic cells in vivo. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly RD, Ngo M, Aglyamova GV, Agarwala S. Regulation of ventral midbrain patterning by Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2007;134:2115–2124. doi: 10.1242/dev.02850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briata P, Ilengo C, Corte G, Moroni C, Rosenfeld MG, Chen CY, Gherzi R. The Wnt/beta-catenin-->Pitx2 pathway controls the turnover of Pitx2 and other unstable mRNAs. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1201–1211. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MA, Caviness VS, Jr, Schneider GE. Development of cell and fiber lamination in the mouse superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1986;248:395–409. doi: 10.1002/cne.902480308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedtsova N, Quina LA, Wang S, Turner EE. Regulation of the development of tectal neurons and their projections by transcription factors Brn3a and Pax7. Dev Biol. 2008;316:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedtsova NG, Turner EE. Brn-3.0 expression identifies early post-mitotic CNS neurons and sensory neural precursors. Mech Dev. 1995;53:291–304. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra MG, Kalsbeek A, van Galen H. Neonatal lesions of the ventral tegmental area affect monoaminergic responses to stress in the medial prefrontal cortex and other dopamine projection areas in adulthood. Brain Res. 1992;596:169–182. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91545-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri AL, Lin W, Mavromatakis YE, Wang JC, Sasaki H, Whitsett JA, Ang SL. Foxa1 and Foxa2 regulate multiple phases of midbrain dopaminergic neuron development in a dosage-dependent manner. Development. 2007;134:2761–2769. doi: 10.1242/dev.000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey LJ, Jones EG, Powell TP. Interrelationships of striate and extrastriate cortex with the primary relay sites of the visual pathway. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1968;31:135–157. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.31.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan KB, Agarwala S, Ragsdale CW. PHOX2A regulation of oculomotor complex nucleogenesis. Development. 2010;137:1205–1213. doi: 10.1242/dev.041251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joksimovic M, Anderegg A, Roy A, Campochiaro L, Yun B, Kittappa R, McKay R, Awatramani R. Spatiotemporally separable Shh domains in the midbrain define distinct dopaminergic progenitor pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19185–19190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904285106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kala K, Haugas M, Lillevali K, Guimera J, Wurst W, Salminen M, Partanen J. Gata2 is a tissue-specific post-mitotic selector gene for midbrain GABAergic neurons. Development. 2009;136:253–262. doi: 10.1242/dev.029900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumaru H, Murakami F, Wu JY, Tsukahara N. GABAergic intrinsic interneurons in the red nucleus of the cat demonstrated with combined immunocytochemistry and anterograde degeneration methods. Neurosci Res. 1984;1:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(84)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kele J, Simplicio N, Ferri AL, Mira H, Guillemot F, Arenas E, Ang SL. Neurogenin 2 is required for the development of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Development. 2006;133:495–505. doi: 10.1242/dev.02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustov AA, Robinson DL. Shared neural control of attentional shifts and eye movements. Nature. 1996;384:74–77. doi: 10.1038/384074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moal M, Simon H. Mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic network: functional and regulatory roles. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:155–234. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, Sooksawate T, Yanagawa Y, Isa K, Isa T, Hall WC. Identity of a pathway for saccadic suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6824–6827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701934104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Metzakopian E, Mavromatakis YE, Gao N, Balaskas N, Sasaki H, Briscoe J, Whitsett JA, Goulding M, Kaestner KH, Ang SL. Foxa1 and Foxa2 function both upstream of and cooperatively with Lmx1a and Lmx1b in a feedforward loop promoting mesodiencephalic dopaminergic neuron development. Dev Biol. 2009;333:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Liu W, Palie J, Lu MF, Brown NA, Martin JF. Pitx2c patterns anterior myocardium and aortic arch vessels and is required for local cell movement into atrioventricular cushions. Development. 2002;129:5081–5091. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan M, Pagan-Westphal SM, Smith DM, Paganessi L, Tabin CJ. The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals. Cell. 1998;94:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunenburger L, Kleiser R, Stuphorn V, Miller LE, Hoffmann KP. A possible role of the superior colliculus in eye-hand coordination. Prog Brain Res. 2001;134:109–125. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)34009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, Lein ES, Zeng H. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2009;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DM, Skidmore JM, Fox SE, Gage PJ, Camper SA. Pitx2 distinguishes subtypes of terminally differentiated neurons in the developing mouse neuroepithelium. Dev Biol. 2002;252:84–99. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DM, Skidmore JM, Philips ST, Vieira C, Gage PJ, Condie BG, Raphael Y, Martinez S, Camper SA. PITX2 is required for normal development of neurons in the mouse subthalamic nucleus and midbrain. Dev Biol. 2004;267:93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaffie JG, Beninato M, Stein BE, Spencer RF. Postnatal development of acetylcholinesterase in, and cholinergic projections to, the cat superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313:113–131. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler WR, Feferman ME, Nauta WJ. Ascending axon degeneration following anterolateral cordotomy. An experimental study in the monkey. Brain. 1960;83:718–750. doi: 10.1093/brain/83.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Stein BE. Visual, auditory, and somatosensory convergence on cells in superior colliculus results in multisensory integration. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:640–662. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi G, Bessho Y, Yamada S, Kageyama R. Identification of a novel basic helix-loop-helix gene, Heslike, and its role in GABAergic neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3672–3682. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5327-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize RR, Butler GD. Postembedding immunocytochemistry demonstrates directly that both retinal and cortical terminals in the cat superior colliculus are glutamate immunoreactive. J Comp Neurol. 1996;371:633–648. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960805)371:4<633::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney RD, Bennett-Clarke CA, King TD, Rhoades RW. Tectospinal neurons in hamster contain glutamate-like immunoreactivity. Brain Res. 1990;537:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90390-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani T, Minaki Y, Kumai M, Ono Y. Helt determines GABAergic over glutamatergic neuronal fate by repressing Ngn genes in the developing mesencephalon. Development. 2007;134:2783–2793. doi: 10.1242/dev.02870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T, Fujisawa H. Alteration of the retinotectal projection map by the graft of mesencephalic floor plate or sonic hedgehog. Development. 2000;127:1899–1910. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.9.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier E, Corvisier J, Pauluis Q, Hardy O. Evidence for glutamatergic tectotectal neurons in the cat superior colliculus: a comparison with GABAergic tectotectal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2354–2366. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltopuro P, Kala K, Partanen J. Distinct requirements for Ascl1 in subpopulations of midbrain GABAergic neurons. Dev Biol. 2010;343:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Balaguer A, Puelles E, Wurst W, Martinez S. Shh dependent and independent maintenance of basal midbrain. Mech Dev. 2009;126:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash N, Puelles E, Freude K, Trumbach D, Omodei D, Di Salvio M, Sussel L, Ericson J, Sander M, Simeone A, Wurst W. Nkx6-1 controls the identity and fate of red nucleus and oculomotor neurons in the mouse midbrain. Development. 2009;136:2545–2555. doi: 10.1242/dev.031781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash N, Wurst W. Genetic networks controlling the development of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Physiol. 2006;575:403–410. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AK, Blumberg B, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Yonei-Tamura S, Tamura K, Tsukui T, de la Pena J, Sabbagh W, Greenwald J, Choe S, Norris DP, Robertson EJ, Evans RM, Rosenfeld MG, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Pitx2 determines left-right asymmetry of internal organs in vertebrates. Nature. 1998;394:545–551. doi: 10.1038/29004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders TA, Lumsden A, Ragsdale CW. Arcuate plan of chick midbrain development. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10742–10750. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10742.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani AM, Skidmore JM, Ramaprakash H, Trumpp A, Gage PJ, Martin DM. Nestin-Cre mediated deletion of Pitx2 in the mouse. Genesis. 2006;44:336–344. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkjaer T, Miller L, Andersen T, Houk JC. Synaptic linkages between red nucleus cells and limb muscles during a multi-joint motor task. Exp Brain Res. 1995;102:546–550. doi: 10.1007/BF00230659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JM, Cramer JD, Martin JF, Martin DM. Cre fate mapping reveals lineage specific defects in neuronal migration with loss of Pitx2 function in the developing mouse hypothalamus and subthalamic nucleus. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:696–707. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks DL, Mays LE. Signal transformations required for the generation of saccadic eye movements. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:309–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tago H, Kimura H, Maeda T. Visualization of detailed acetylcholinesterase fiber and neuron staining in rat brain by a sensitive histochemical procedure. J Histochem Cytochem. 1986;34:1431–1438. doi: 10.1177/34.11.2430009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SS, Valcanis H, Kalloniatis M, Harvey A. Cellular dispersion patterns and phenotypes in the developing mouse superior colliculus. Dev Biol. 2002;241:117–131. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Lovicu F, Ziman M. The role of Pax7 in determining the cytoarchitecture of the superior colliculus. Dev Growth Differ. 2004;46:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169x.2004.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Zembrzycki A, Mansouri A, Ziman M. Pax7 is requisite for maintenance of a subpopulation of superior collicular neurons and shows a diverging expression pattern to Pax3 during superior collicular development. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay JJ, Lanctot C, Drouin J. The pan-pituitary activator of transcription, Ptx1 (pituitary homeobox 1), acts in synergy with SF-1 and Pit1 and is an upstream regulator of the Lim-homeodomain gene Lim3/Lhx3. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:428–441. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.3.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallstedt A, Muhr J, Pattyn A, Pierani A, Mendelsohn M, Sander M, Jessell TM, Ericson J. Different levels of repressor activity assign redundant and specific roles to Nkx6 genes in motor neuron and interneuron specification. Neuron. 2001;31:743–755. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F. The neuropil in superficial layers of the superior colliculus of the mouse. A correlated Golgi and electron microscopic study. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1973;142:117–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00519719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuillon-Cacciuttolo G, Bosler O, Nieoullon A. GABA neurons in the cat red nucleus: a biochemical and immunohistochemical demonstration. Neurosci Lett. 1984;52:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Nakamura H. Control of chick tectum territory along dorsoventral axis by Sonic hedgehog. Development. 2000;127:1131–1140. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.5.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmoreland JJ, McEwen J, Moore BA, Jin Y, Condie BG. Conserved function of Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-30 and mouse Pitx2 in controlling GABAergic neuron differentiation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6810–6819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06810.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickelgren BG. Superior colliculus: some receptive field properties of bimodally responsive cells. Science. 1971;173:69–72. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3991.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo HH, Jen LS, So KF. The postnatal development of retinocollicular projections in normal hamsters and in hamsters following neonatal monocular enucleation: a horseradish peroxidase tracing study. Brain Res. 1985;352:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagoraiou L, Akay T, Martin JF, Brownstone RM, Jessell TM, Miles GB. A cluster of cholinergic premotor interneurons modulates mouse locomotor activity. Neuron. 2009;64:645–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.