Abstract

The mechanisms associated with hepatitis B viral (HBV) induced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remain elusive and currently, there are no well-established animal models to study this disease. Using the Sleeping Beauty transposon as a delivery system, we introduced an oncogenic component of HBV, namely the hepatitis B virus X (HBx) gene to the livers of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah) mutant mice via hydrodynamic tail vein injections. Coexpression of the Fah cDNA from the transposon vector allows for the selective repopulation of genetically corrected hepatocytes in Fah mutant mice. The process of hydrodynamic delivery induces liver inflammation and the subsequent selective repopulation of hepatocytes carrying the transgene(s) can provide useful genetic information on the mechanisms of HBV-induced hyperplasia. Short hairpin RNA directed against the Trp53 gene (shp53) or other tumor suppressor genes, and oncogenes, like the constitutively active NRASG12V, can also be codelivered with HBx using this system to determine if oncogenic cooperation exists. In this study, we find that expression of HBx induced activation of β-catenin expression in hydrodynamically injected livers, indicating its association with the Wnt signaling pathway in HBV-induced hyperplasia. HBx coinjected with shp53 accelerated the formation of liver hyperplasia in these mice. As expected, constitutively active NRASG12V alone was sufficient to induce liver hyperplasia and its tumorigenicity was augmented when coinjected with shp53. Interestingly, HBx does not seem to cooperate with constitutively active NRASG12V in driving liver tumorigenesis. This system can be used as a model for studying the various genetic contributions of HBV to liver hyperplasia and finally HCC in an in vivo system.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis gene X, transposable elements, hydrodynamic delivery, mouse model

Introduction

Activation of proto-oncogenes, combined with loss of tumor suppressor genes generated by epigenetic and genetic mechanisms have all been implicated in the tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Presently, there is no consensus on the number of different HCC molecular subtypes although a recent meta-analysis based on gene expression and genetic changes suggests three main subtypes (1). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection appears to play multiple roles in hepatocellular carcinogenesis (2). The study of HBV pathogenesis has been difficult because no good animal model currently exists that combines hepatocyte necrosis and repopulation along with facile viral gene delivery.

The unique regulatory component gene X of HBV encodes a 17-kDa protein called Hepatitis B virus X (HBx) (154 amino acid residues). The HBx gene has been shown to induce cell proliferation, pro-apoptotic and stress responses, activate certain signal transduction pathways, DNA-repair mechanisms and induce transformation (3). The effects of HBx as a transgene in mice have produced variable effects (4–6). If and how it can induce HCC in transgenic mice remains unclear.

The oncogenic mechanisms of HBx are also controversial. HBx has been variably reported to activate STAT3, WNT/CTNNB1 or bind to and inactivate the TP53 protein (7–11). The critical activators of HBx in HCC induction have been difficult to identify because no efficient and rapid system for in vivo gene delivery and oncogenesis has been available. In order to elucidate the effect of HBx in vivo, we utilized the Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon system to deliver this transgene stably via hydrodynamic tail vein injection into the livers of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah)-deficient mice (12). Since mutations in TP53 are common in patients with HBV induced HCC, we cointroduced a transposon containing a RNA short hairpin directed against the Trp53 gene to study this relationship. Also, to elucidate whether any relationship exists between HBx infection and NRAS mutations, a transposon containing a constitutively active NRAS oncogene (G12V) was also cointroduced with HBx. Using this model, we are able to mimic HBx expression following HBV infection, followed by subsequent repopulation of HBV-infected hepatocytes in the liver.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Fah-deficient/Rosa26-SB11 mice

All animal work was conducted under an institutionally approved animal welfare protocol. The generation, maintenance and genotyping of doubly transgenic mice (Fah−/−; Rosa26-SB11) (13, 14) as described in Supplementary Methods.

Generation of transgenes used for hydrodynamic tail vein injections

We generated the pKT2/Gene Delivery (GD) plasmid carrying HBx, NRASG12V (NRAS), Gfp, empty vector or transposon vector containing the short hairpin RNA directed against Trp53 (15) (pKT2/GD-HBx, pKT2/GD-NRAS, pKT2/GD-Gfp, pKT2/GD-Empty or pT2/shp53, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 1A), using standard molecular cloning techniques. Detailed steps as described in Supplementary Methods.

Hydrodynamic tail vein injections

Twenty micrograms of each construct was hydrodynamically injected into 4 to 6-week old male doubly transgenic mice as described previously (16). These mice are normally maintained on 2-(2-nitro-4-tri uoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC) drinking water but replaced on normal drinking water immediately after hydrodynamic injection of transposon vector(s).

Liver analysis

Whole livers were removed, weighed and the number of visible macroscopic hyperplastic nodules counted. Reasonably sized nodules were carefully removed for DNA and RNA extraction. Histological sections were also taken for larger nodules for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) or immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses as described in Supplementary Methods.

Blood serum analyses

Alanine transaminase (ALT) level in blood serum samples was analyzed by Marshfield Laboratories (Wisconsin, USA).

RT-PCR

Detailed protocol as described in Supplementary Methods.

Results

Effect of HBx transgene during selective liver repopulation

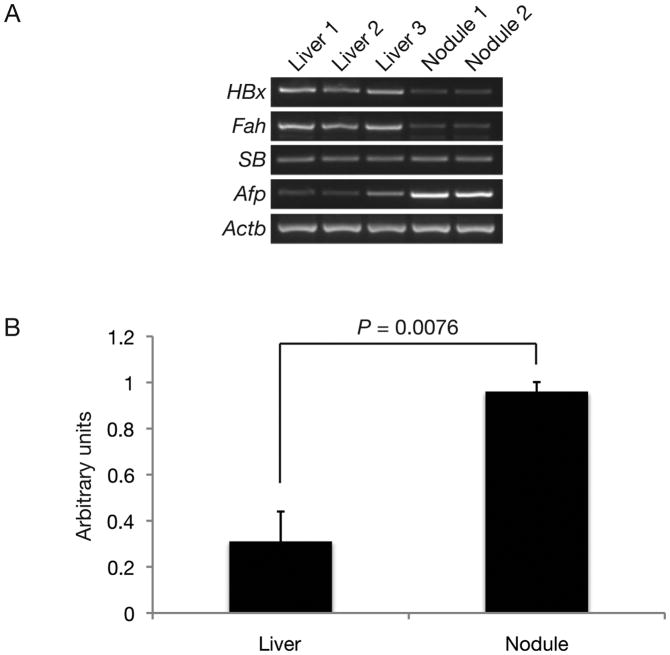

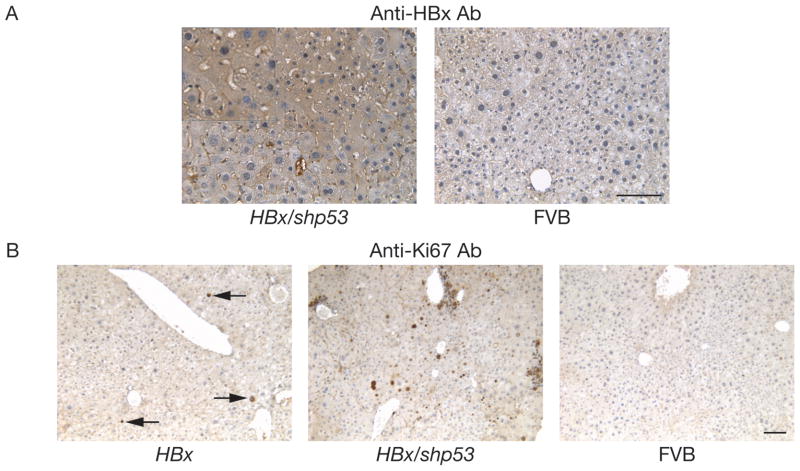

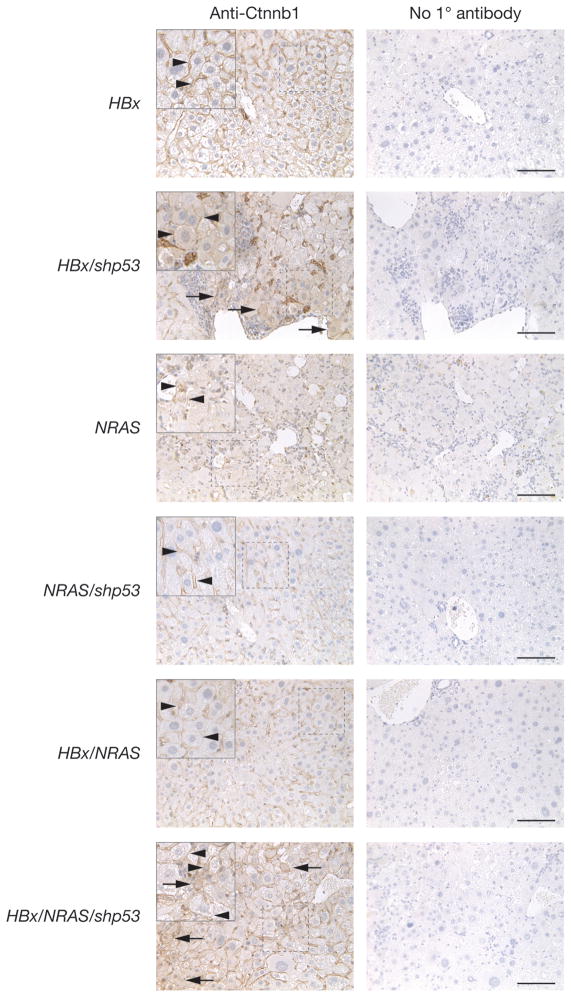

Mice injected with HBx alone (Supplementary Figure 1A) were observed up to 139-days post-hydrodynamic injection (PHI) (n = 16). The detection of Luciferase activity at 48-days PHI indicated selective repopulation of the liver as a result of stable transgene integration into the mouse genome mediated by SB transposition (Supplementary Figure 1B, top). The majority of HBx animal livers displayed no evidence of hyperplasia (88%). However, two HBx animals sacrificed at 74- and 139-days PHI displayed livers with hyperplastic nodules (Supplementary Figure 1C). Hyperplastic nodules isolated at 139-days PHI were positive for HBx transcripts by RT-PCR (Figure 1A). These hyperplastic nodules expressed high levels of alpha-fetoprotein (Afp), a known diagnostic marker for HCC, when compared to adjacent normal liver (Figure 1A). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses for arbitrary expression levels of Afp relative to β-actin (Actb) were 0.31 ± 0.13 compared to 0.96 ± 0.042 (mean ± SD) in normal livers and hyperplastic nodules, respectively (P = 0.0076) (Figure 1B). In order to visualize the selective hepatocyte repopulation process, control mice injected with Gfp alone (Supplementary Figure 1A) were observed up to 113-days PHI (n = 4). The detection of Luciferase activity at 48-days PHI also indicated selective repopulation of the liver (Supplementary Figure 1B, bottom). These Gfp mice were sacrificed at 82- and 113-days PHI (n = 4). Although no hyperplastic nodules were initially detected at 82-days PHI (n = 2), 1 single Gfp-negative nodule was detected at 113-days PHI (n = 2). Gfp expression pattern confirmed that the liver repopulation process occurred uniformly when viewed using fluorescent imaging (Supplementary Figure 1D). Importantly, control mice coinjected with empty vector and short hairpin RNA directed against Trp53 (empty/shp53) (Supplementary Figure 1A) were negative for hyperplasia up to 139-days (n = 9). Interestingly, Ki67 staining did not show significant increase in mitotic index with Gfp animals (data not shown). However, there were higher levels of Ki67 staining in HBx animals (Figure 2B). Liver weight percentage of HBx mice was significantly higher than Gfp (P < 0.01) and empty/shp53 (P < 0.001) controls (Figure 3B), indicating that HBx may have a proliferative effect on hepatocytes. Mice injected with HBx alone had high levels of β-catenin (Ctnnb1) expression by IHC, which was mainly localized to the cellular membrane of repopulated hepatocytes (Figure 5). Livers of HBx mice had hardly detectable levels of pAkt (Figure 6) and displayed more CD45 staining cells by IHC when compared with control Gfp animals (Supplementary Figure 4). Interestingly, ALT levels amongst HBx, empty/shp53 and Gfp representative animals were not significantly different (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Proliferative and oncogenic potential of HBx in a selectively repopulating liver. (A) RT-PCR analyses of liver nodules and adjacent normal liver at 139-days PHI expressed HBx and Fah transgenes. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of RT-PCR from (A) demonstrated significantly higher Afp expression in hyperplastic nodules compared with adjacent normal livers (P = 0.0076, unpaired t test) relative to Actb levels.

Figure 2.

Augmented oncogenic potential of HBx with shp53 in a selectively repopulating liver. (A) Representative demonstration of HBx-positive hepatocytes by IHC in a 71-day PHI HBx/shp53 mouse (see also magnified insert in upper-left corner of area indicated by dashed box). HBx was not detected in normal FVB liver. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Representative demonstration of high mitotic index by Ki67 IHC in a 71-day PHI HBx/shp53 mouse. Representative field of view containing several Ki67-positive cells (arrows) in a 78-day PHI HBx mouse. Ki67 was not detected in normal FVB liver. Scale bar, 100 μm. Negative controls for (A) and (B), serial sections incubated without the indicated primary antibodies gave no visible signals above background (data not shown).

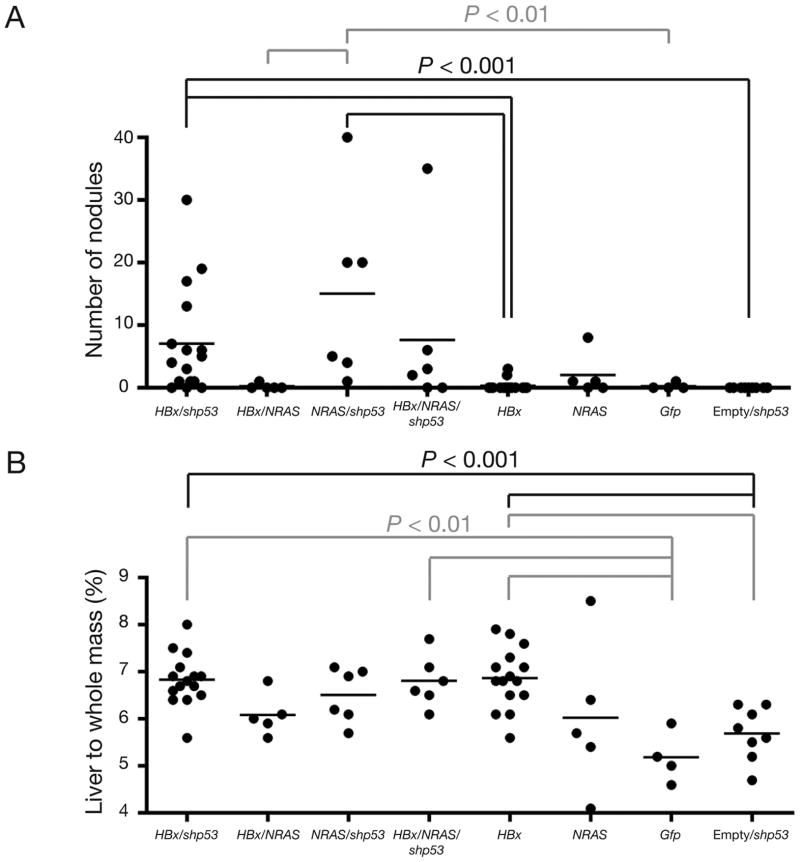

Figure 3.

NRAS does not cooperate with HBx in liver tumorigenesis during selective repopulation. (A) Statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney two-tail test indicated a highly significance difference (P < 0.001, black lines) in the number of nodules between indicated cohorts. Significant differences (P < 0.01, grey lines) in the number of nodules were seen between indicated cohorts. Marginal significances (P < 0.05) in the number of nodules were seen between HBx/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS, HBx/shp53 vs Gfp, HBx vs HBx/NRAS/shp53 and empty/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS/shp53 (not indicated). (B) Statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney two-tail test indicated a highly significance difference (P < 0.001, black lines) in the percentage of liver weight relative to the whole mouse mass from each injected cohort. Statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney two-tail test indicated a significance difference (P < 0.01, grey lines) in the liver weight percentage between indicated cohorts. Marginal significances (P < 0.05) in the liver weight percentage were seen between HBx/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS, HBx vs HBx/NRAS, empty/shp53 vs NRAS/shp53, NRAS/shp53 vs Gfp and HBx/shp53 vs Gfp (not indicated).

Figure 5.

Oncogenic potential of HBx is associated with the Wnt signaling pathway. IHC staining of serial liver sections taken from experimental animals injected with the indicated transgene(s) using antibody against Ctnnb1. HBx, 78-day PHI experimental animal injected with HBx alone. HBx/shp53, 72-day PHI experimental animal injected with HBx and shp53. NRAS, an 82-day PHI experimental animal injected with NRAS alone. NRAS/shp53, a 71-day PHI experimental animal injected with NRAS and shp53. HBx/NRAS, a 71-day PHI experimental animal injected with HBx and NRAS. HBx/NRAS/shp53, a 71-day PHI experimental animal injected with HBx, NRAS and shp53. Left column, sections were incubated with anti-Ctnnb1. Right column, no primary antibody was used. Magnified inserts in upper-left corner of areas indicated by dashed boxes. Arrows and arrowheads indicate Ctnnb1 cytoplasmic and membranous staining detected in indicated cells, respectively; scale bars, 100 μm.

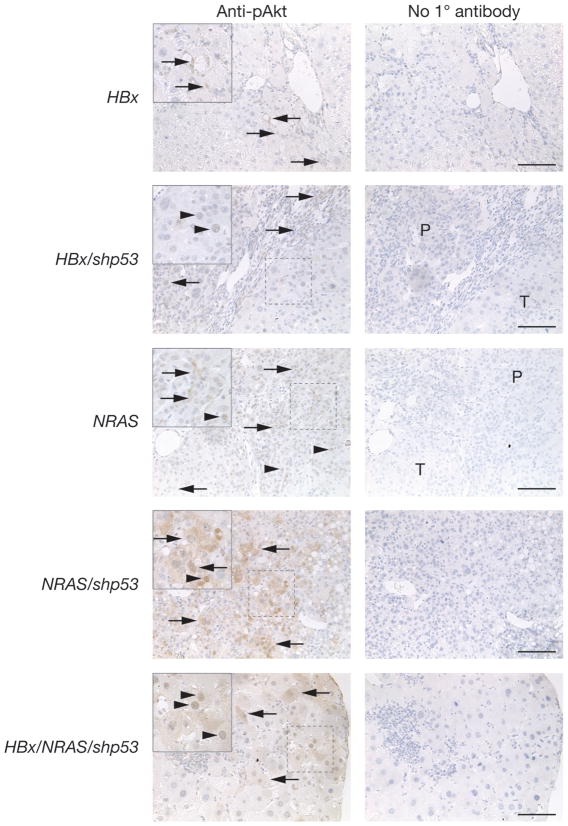

Figure 6.

Oncogenic potential of NRAS is associated with the Pi3k/Akt signaling pathway. IHC staining of serial liver sections taken from experimental animals injected with the indicated transgene(s) using antibody against pAkt. HBx, HBx/shp53, NRAS, NRAS/shp53 and HBx/NRAS/shp53 as described in Figure 5. Left column, sections were incubated with anti-pAkt. Right column, no primary antibody was used. Magnified inserts in upper-left corner of areas indicated by dashed boxes. Arrows and arrowheads indicate pAkt cytoplasmic and nuclear staining detected in indicated cells, respectively; P, parenchymal; T, hyperplastic nodule; scale bars, 100 μm.

Table 1.

ALT serum levels in representative experimental animals injected with various transgene(s)

| Transgene(s) injected | n | PHI | ALT (U/L) Mean ± SD |

Nodules/appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gfp | 4 | 82 and 113 | 61.3 ± 22.3 | Normal to 1 nodule |

| Empty/shp53 | 5 | 70 to 131 | 87.0 ± 28.3 | Normal |

| HBx | 9 | 71 to 78 | 79.7 ± 29.5 | Rough to 3 nodules |

| HBx/shp53 | 9 | 71 to 74 | 146.8 ± 83.2 | Rough to 30 nodules |

| HBx/NRAS | 5 | 71 and 72 | 43.2 ± 25.5 | Slightly rough to 1 nodule |

| HBx/NRAS/shp53 | 6 | 61 to 72 | 157 ± 110.9 | Normal to 35 nodules |

| NRAS | 5 | 82 | 57.6 ± 42.2 | Normal to 8 nodules |

| NRAS/shp53 | 6 | 61 and 71 | 89.7 ± 19.0 | 1 to 40 nodules |

Gfp, pKT2/GD-Gfp; Empty/shp53, pKT2/GD-Empty and pT2/shp53; HBx, pKT2/GD-HBx; HBx/shp53; pKT2/GD-HBx and pT2/shp53; HBx/NRAS, pKT2/GD-HBx and pKT2/GD-NRAS; HBx/NRAS/shp53, pKT2/GD-HBx, pKT2/GD-NRAS and pT2/shp53; NRAS, pKT2/GD-NRAS; NRAS/shp53, pKT2/GD-NRAS and pT2/shp53; PHI, age of experimental animals in days sacrificed post-hydrodynamic injection; n, number of animals tested in each cohort; ALT, alanine transaminase level in blood serum; Normal, indicates no abnormalities; Slightly rough, texture of liver was slightly rough in appearance; Rough texture, texture of liver was rough in appearance; Nodule, hyperplastic liver nodule(s) detected.

Synergistic effect of HBx and shp53 transgenes for tumorigenesis during selective liver repopulation

Mice injected with HBx and short hairpin RNA against Trp53 (shp53) (Supplementary Figure 1A) (HBx/shp53) were observed up to 139-days PHI (n = 16). HBx/shp53 animals were sacrificed at various time points between 63- and 139-days PHI. Although no hyperplastic nodules were initially detected at 63-days PHI, the HBx/shp53 mouse liver had a rough surface texture (Supplementary Figure 2A, middle), indicating possible hyperproliferation and/or hyperplasia. The rough textured liver was also Gfp-positive (detection of the Gfp reporter gene within shp53) and nodular in appearance when viewed under a fluorescent microscope (Supplementary Figure 2B, middle). Empty/shp53 mice were sacrificed at various time points between 63- and 139-days PHI (n = 9). No hyperplasia was seen in the liver of empty/shp53 mouse at 63-days PHI (Supplementary Figure 2A, left) and uniform Gfp expression was detected throughout the liver (Supplementary Figure 2B, left). In contrast, 86% of HBx/shp53 mice (n = 7) sacrificed at around 70-days PHI had multiple hyperplastic nodules (Supplementary Figure 2A, right) that were Gfp-positive (Supplementary Figure 2B, right). Livers of empty/shp53 mice observed at various time points were normal and had relatively uniform Gfp expression throughout the liver (data not shown). The majority of hyperplastic nodules isolated from HBx/shp53 animals at 72-days PHI were Gfp-positive and the presence of HBx and/or shp53 was confirmed by both RT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 2C) and IHC (Figure 2A). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated no statistical differences in Afp expression levels between hyperplastic nodules and adjacent normal livers isolated from 72-day PHI HBx/shp53 animals (Supplementary Figure 2D). However, significant differences in Afp expression levels were seen between (i) empty/shp53 vs HBx/shp53 normal livers (P = 0.0035) and (ii) normal empty/shp53 livers vs HBx/shp53 nodules (P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Figure 2D). HBx was detected in HBx/shp53 livers (Figure 2A) and these animals generally had higher levels of Ki67 by IHC compared to animals injected with HBx alone (Figure 2B). Although HBx alone was capable of inducing hyperplasia at low penetrance (74-days PHI) or after prolonged latency (139-days PHI), its oncogenic potential was augmented as shown by reduced latency to 71-days PHI and greater tumor multiplicity with the coinjection of shp53 transgene. HBx/shp53 mice had comparable levels of Ctnnb1 by IHC to mice injected with HBx alone (Figure 5). Expression of Ctnnb1 was mainly localized to the cellular membrane of HBx repopulated hepatocytes (Figure 5). In addition to membranous Ctnnb1 staining, cytoplasmic staining was also detected in some hepatocytes of HBx/shp53 animals (Figure 5). Hyperplastic nodules taken from an HBx/shp53 animal were weakly positive for pAkt (Figure 6) and displayed more CD45 staining cells by IHC when compared with Gfp animals (Supplementary Figure 4). ALT levels in representative HBx/shp53 experimental animals were marginally significantly higher (P < 0.05) than Gfp or HBx animals and displayed a non-statistically significant trend towards higher ALT levels compared to empty/shp53 animals (Table 1).

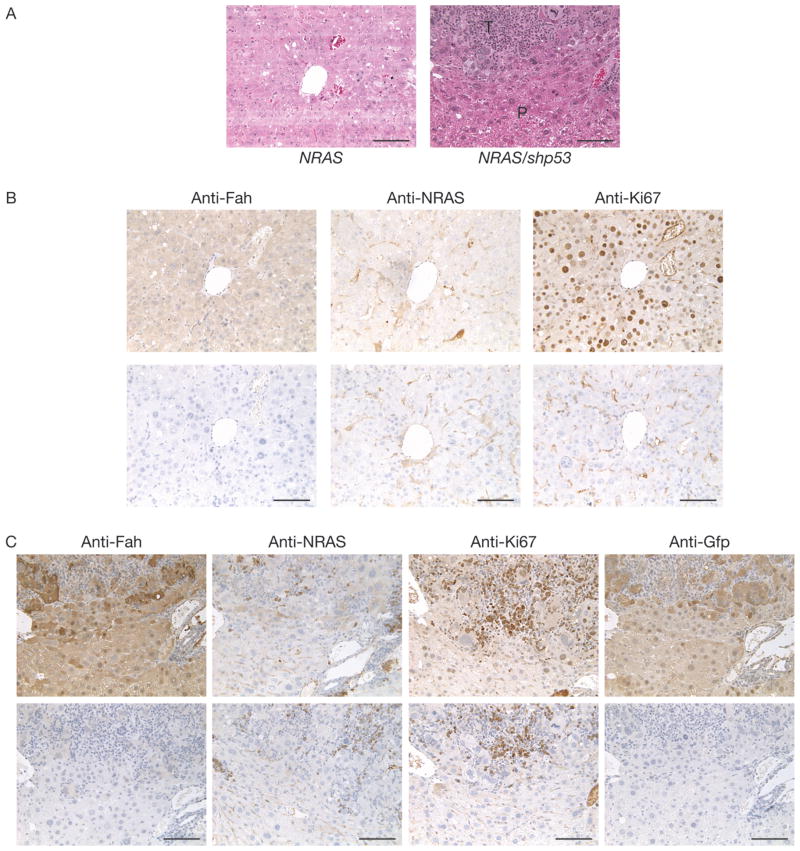

HBx does not cooperate with NRASG12V in accelerating liver tumorigenesis during selective liver repopulation

Hyperplasia was detected in 60% of mice injected with NRASG12V (NRAS, Supplementary Figure 1A) after 82-days PHI (n = 5) (Supplementary Figure 3A, left). Histological analyses of these hyperplastic nodules by HE staining (Figure 4A, left) and IHC confirmed the detection of NRAS in these nodules (Figure 4B). This tumorigenic potential was augmented when mice were coinjected with shp53 (NRAS/shp53), as shown by the accelerated detection of hyperplasia by 61-days PHI (n = 2). By 71-days PHI, hyperplasia was detected in all remaining NRAS/shp53 mice (n = 4) (Supplementary Figure 3A, middle). NRAS/shp53 livers were Gfp-positive macroscopically (Supplementary Figure 3C, left) and shown to express Gfp and NRAS by RT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 3D). Histological analyses of these hyperplastic nodules by HE staining (Figure 4A, right) and IHC confirmed that NRAS and shp53 contributed to the tumorigenesis (Figure 4C). NRAS/shp53 animals displayed a non-statistically significant trend towards higher ALT levels compared to NRAS or Gfp animals (Table 1). NRAS/shp53 livers displayed more CD45+ staining cells than Gfp or NRAS (Supplementary Figure 4). In contrast, in mice coinjected with HBx and NRAS transgenes (HBx/NRAS) (n = 5), only 1 hyperplastic nodule was isolated from a single experimental mouse after 70-days PHI (Supplementary Figure 3A, right). Besides this, the livers isolated from remaining HBx/NRAS mice were macroscopically normal in appearance (data not shown). Interestingly, HBx/NRAS livers displayed more CD45+ staining cells than Gfp or NRAS (Supplementary Figure 4). ALT levels in HBx/shp53 were significantly higher than HBx/NRAS animals (P < 0.01) and marginally significantly higher levels (P < 0.05) were seen in HBx and NRAS/shp53 compared to HBx/NRAS animals (Table 1). When all 3 transgenes were coinjected (HBx/NRAS/shp53), 67% of mice (n = 6) sacrificed at 61- and 71-days PHI displayed multiple hyperplastic nodules (Supplementary Figure 3B). The majority of nodules were Gfp-positive (Supplementary Figure 3C, right) and shown to express Gfp by RT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 3D). Expression of the injected transgenes was detected in the majority of normal livers and hyperplastic nodules isolated from both groups (HBx/NRAS/shp53; NRAS/shp53) (Supplementary Figure 3D). ALT levels between HBx/shp53 and HBx/NRAS/shp53 were similar (Table 1). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses also demonstrated a significant difference in the expression levels of Afp in hyperplastic nodules compared to adjacent normal livers (P = 0.0044, unpaired t test) (data not shown). Statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney two-tail test indicated highly significant differences (P < 0.001) in the number of hyperplastic nodules between HBx/shp53 vs HBx, HBx/shp53 vs empty/shp53, HBx vs NRAS/shp53 and empty/shp53 vs NRAS/shp53. Significant differences (P < 0.01) were seen between NRAS/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS and NRAS/shp53 vs Gfp. Marginal significances (P < 0.05) were seen between HBx/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS, HBx/shp53 vs Gfp, HBx vs HBx/NRAS/shp53 and empty/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS/shp53 (Figure 3A). Statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney two-tail test indicated highly significant differences (P < 0.001) in the weight percentage between HBx/shp53 vs empty/shp53 and HBx vs empty/shp53. Significant differences (P < 0.01) were seen between HBx/shp53 vs Gfp, HBx vs Gfp, empty/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS/shp53 and HBx/NRAS/shp53 vs Gfp. Marginal significances (P < 0.05) were seen between HBx/shp53 vs HBx/NRAS, HBx vs HBx/NRAS, empty/shp53 vs NRAS/shp53, NRAS/shp53 vs Gfp and HBx/shp53 vs Gfp (Figure 3B). Mice injected with NRAS alone generally had weak expression levels of Ctnnb1 detectable by IHC (Figure 5). Hyperplastic nodules induced by NRAS coinjected with shp53 generally had higher Ctnnb1 expression levels but not at levels seen in HBx or HBx/shp53 mice (Figure 5). As expected, HBx/NRAS mice had heterogeneous staining patterns for Ctnnb1 (Figure 5). In contrast, hyperplastic nodules from NRAS or NRAS/shp53 mice were highly positive for pAkt by IHC (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Oncogenic potential of NRAS alone or in combination with shp53 in a selectively repopulating liver. (A) HE staining of hyperplastic nodule sections taken from experimental animals injected with NRAS alone at 82-days PHI (left) or in combination with shp53 at 71-days PHI (right). P, parenchymal; T, hyperplastic nodule; scale bars, 100 μm. (B) IHC staining of hyperplastic nodule serial sections taken from experimental animals injected with NRAS alone at 82-days PHI using antibodies against Fah (left), NRAS (middle) and Ki67 (right). Top panels, sections were incubated with the indicated antibodies. Bottom panels, no primary antibodies were used. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) IHC staining of hyperplastic nodule serial sections taken from NRAS/shp53 experimental animals at 71-days PHI using antibodies against Fah (left), NRAS (middle left), Ki67 (middle right) and Gfp (right). Top panels, sections were incubated with the indicated antibodies. Bottom panels, no primary antibodies were used. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Discussion

Using the Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon system and hydrodynamically introducing transgenes specifically into the livers of Fah-null/SB transposase expressing recipient mice, we can dissect the contributions of various gene components of HBV by inducing liver hyperplasia in these animals. Our results demonstrate the oncogenic effect of HBx transgene when hydrodynamically delivered into hepatocytes repopulating a liver. The low penetrance or delayed tumorigenic latency of HBx in injected mice may reflect the long latency of HBV-induced cirrhosis and tumorigenesis in infected humans. The fact that we observed an effect of HBx alone may indicate its expression can cooperate with the process of hepatocyte regrowth to induce liver hyperplasia. Mice injected with HBx alone seem to have higher liver to whole mass percentages, indicating that HBx may have a hyperproliferative effect during HBV-induced liver tumorigenesis (Figure 3B). Tumor latency was reduced and the oncogenic effect augmented when HBx was coinjected with a short hairpin RNA directed against Trp53. This is especially important as ~50% of human patients with HCC have mutations in the TP53 gene. HBx has been shown to bind TP53 and inactivate its activity (9, 11) but our data indicates this mechanism must not impair TP53 function sufficiently for tumor formation. Therefore, TP53 mutant hepatocytes in a patient who acquires an HBV infection would likely lead to an enhanced risk of transformation to HCC.

Our results indicate that HBx does not seem to cooperate with constitutively active NRAS to induce liver tumorigenesis in HBx/NRAS animals. This was evident by relatively low ALT levels in serum (Table 1), low tumor multiplicity and liver weight to whole mass percentage (Figures 3A and 3B) in HBx/NRAS mice. HBx has been suggested to upregulate the Ras signaling pathway (17). Perhaps HBx expression and activated Ras are redundant in this transformation assay. Even when all transgenes were coinjected (HBx/NRAS/shp53), there was only marginally significant increase (P < 0.05) in tumorigenicity when compared with HBx alone. No significant increase in tumorigenicity was also seen in HBx/NRAS animals when compared to NRAS alone (Figure 3A). Our results indicate that HBx upregulates the Wnt signaling pathway and this may play a role in liver tumorigenesis (Figure 5), while constitutively active NRAS seems to induce hyperplasia probably via the RAF/MEK/ERK and/or PI3K/AKT associated pathways (Figure 6). In addition, we detected high levels of CD45+ staining cells in livers of animals injected with HBx alone or in combination with other transgenes (Supplementary Figure 4). These cells could represent infiltrating lymphocytes that are often associated with HBV infection. Indeed, the HBx protein would be predicted to act as a foreign antigen in our system, unlike in previously reported HBx transgenic mouse models. HBx-induced inflammation may play some role in HCC progression, a hypothesis that could be tested using our model. Elevated pAkt levels were detected by IHC in experimental animals injected with NRAS alone or in combination with shp53, indicating that NRAS is likely signaling via the Pi3k/Akt pathway (Figure 6). HBx has been previously shown to activate WNT/CTNNB1 signaling pathway in human hepatoma cell lines (8). HBx antigen has also been associated with the accumulation of CTNNB1 in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus and the upregulation of the HBx antigen effector URG11, resulting in increased activation of CTNNB1 (18). CTNNB1 staining pattern can be correlated with the histopathological type of liver tumors (19). The absence of nuclear staining and strong membranous staining with rare weak cytoplasmic expression of Ctnnb1 suggests the hyperplastic nodules induced by HBx or HBx/shp53 were adenocarcinomas or poorly differentiated HCC (Figure 5). We did not detect any activation of Stat3 in liver tumors expressing HBx by IHC in our experimental cohorts using a phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) specific antibody (data not shown) despite previous suggestions that HBx activates Stat3 (7). Finally, it should be stated that there will be a subpopulation Fah-null cells that can escape the selection process by activating the survival Akt pathway caused by hepatic stress (20). These cells can evolve by acquiring additional mutations and result in hyperplastic nodules not associated with the injected transgenes. Examples of such background Fah-negative nodules were seen in HBx/shp53 and HBx/NRAS/shp53 mice (Supplementary Figures 2C and 3D, respectively). These nodules were negative for the injected transgenes by RT-PCR. Such occurrence of background tumors only occur at low incidence and can be segregated from transgene(s) induced tumors by molecular and biochemical tests. Nevertheless, our experience shows that the Fah-deficient mouse model, when combined with the SB transposon system, is useful for in vivo functional validation of HBV genes in liver hyperplastic induction. Therefore, our present study reinforces the previous observations associated with HBV infection and validates the use of our mouse model in studying HBV-induced liver hyperplasia and its progression to HCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

V.W.K., B.R.T. and D.A.L. are supported by a R01 CA132962 grant from the National Cancer Institute. J.B.B. is supported by a R01 DK082516 grant by the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY, Villanueva A, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7385–7392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azam F, Koulaouzidis A. Hepatitis B virus and hepatocarcinogenesis. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, Zhang H, Ye L. Effects of hepatitis B virus X protein on the development of liver cancer. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keasler VV, Lerat H, Madden CR, Finegold MJ, McGarvey MJ, Mohammed EM, Forbes SJ, et al. Increased liver pathology in hepatitis C virus transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus X protein. Virology. 2006;347:466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee TH, Finegold MJ, Shen RF, DeMayo JL, Woo SL, Butel JS. Hepatitis B virus transactivator X protein is not tumorigenic in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1990;64:5939–5947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.5939-5947.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu BK, Li CC, Chen HJ, Chang JL, Jeng KS, Chou CK, Hsu MT, et al. Blocking of G1/S transition and cell death in the regenerating liver of Hepatitis B virus X protein transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:916–928. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bock CT, Toan NL, Koeberlein B, Song le H, Chin R, Zentgraf H, Kandolf R, et al. Subcellular mislocalization of mutant hepatitis B X proteins contributes to modulation of STAT/SOCS signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Intervirology. 2008;51:432–443. doi: 10.1159/000209672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha MY, Kim CM, Park YM, Ryu WS. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential for the activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in hepatoma cells. Hepatology. 2004;39:1683–1693. doi: 10.1002/hep.20245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huo TI, Wang XW, Forgues M, Wu CG, Spillare EA, Giannini C, Brechot C, et al. Hepatitis B virus X mutants derived from human hepatocellular carcinoma retain the ability to abrogate p53-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2001;20:3620–3628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang XW, Forrester K, Yeh H, Feitelson MA, Gu JR, Harris CC. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits p53 sequence-specific DNA binding, transcriptional activity, and association with transcription factor ERCC3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2230–2234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang XW, Gibson MK, Vermeulen W, Yeh H, Forrester K, Sturzbecher HW, Hoeijmakers JH, et al. Abrogation of p53-induced apoptosis by the hepatitis B virus X gene. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6012–6016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grompe M, al-Dhalimy M, Finegold M, Ou CN, Burlingame T, Kennaway NG, Soriano P. Loss of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase is responsible for the neonatal hepatic dysfunction phenotype of lethal albino mice. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2298–2307. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keng VW, Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Dupuy AJ, Ryan BJ, Matise I, Silverstein KA, et al. A conditional transposon-based insertional mutagenesis screen for genes associated with mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:264–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wangensteen KJ, Wilber A, Keng VW, He Z, Matise I, Wangensteen L, Carson CM, et al. A facile method for somatic, lifelong manipulation of multiple genes in the mouse liver. Hepatology. 2008;47:1714–1724. doi: 10.1002/hep.22195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickins RA, Hemann MT, Zilfou JT, Simpson DR, Ibarra I, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Probing tumor phenotypes using stable and regulated synthetic microRNA precursors. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1289–1295. doi: 10.1038/ng1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell JB, Podetz-Pedersen KM, Aronovich EL, Belur LR, McIvor RS, Hackett PB. Preferential delivery of the Sleeping Beauty transposon system to livers of mice by hydrodynamic injection. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3153–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doria M, Klein N, Lucito R, Schneider RJ. The hepatitis B virus HBx protein is a dual specificity cytoplasmic activator of Ras and nuclear activator of transcription factors. Embo J. 1995;14:4747–4757. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lian Z, Liu J, Li L, Li X, Clayton M, Wu MC, Wang HY, et al. Enhanced cell survival of Hep3B cells by the hepatitis B x antigen effector, URG11, is associated with upregulation of beta-catenin. Hepatology. 2006;43:415–424. doi: 10.1002/hep.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvisi DF, Factor VM, Loi R, Thorgeirsson SS. Activation of beta-catenin during hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mouse models: relationship to phenotype and tumor grade. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2085–2091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orejuela D, Jorquera R, Bergeron A, Finegold MJ, Tanguay RM. Hepatic stress in hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (HT1) activates the AKT survival pathway in the fah−/− knockout mice model. J Hepatol. 2008;48:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.